Metal Oxide Nanostructures Chemistry

SYNTHESIS FROM AQUEOUS SOLUTIONS

SECOND EDITION

Jean-Pierre Jolivet

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

Translation of the French language edition of:

De la solution à l’oxyde—2e edition

De Jean-Pierre Jolivet

© 2015 Editions EDP Sciences

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Jolivet, Jean-Pierre, author.

Title: Metal oxide nanostructures chemistry : synthesis from aqueous solutions / Jean-Pierre Jolivet.

Other titles: De la solution a l’oxyde. Chimie aqueuse des cations metalliques, synthese de nanostructures. English

Description: 2nd edition. | New York, NY : Oxford University Press, 2019. | Translation of the French language edition of: De la solution a l’oxyde, 2e edition : chimie aqueuse des cations metalliques, synthese de nanostructures (2015). | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2018045235 | ISBN 9780190928117

Subjects: LCSH: Oxides—Surfaces. | Precipitation (Chemistry) | Metallic oxides. | Nanostructured materials.

Classification: LCC QD181.O1 J6513 2019 | DDC 546/.72159—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018045235

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

Printed by Sheridan Books, Inc., United States of America

CONTENTS

Preface ix

List of Abbreviations xi

1. Nanomaterials: Specificities of Properties and Synthesis 1

1.1 Specific Properties of Nanoparticles 2

1.1.1 Volume Effects 2

1.1.2 Surface Effects 6

1.1.3 The Influence of Size Effect on Thermodynamic, Structure, and Reactivity of Oxide Nanoparticles 7

1.2 Specificity and Requirements in the Fabrication Methods of Nanoparticles 13

2. Water and Metal Cations in Solution 19

2.1 Water as Solvent, Physicochemistry of the Liquid 20

2.1.1 Electronic Structure of the Water Molecule 20

2.1.2 Structure of Liquid Water 22

2.1.3 Hydration of Ions and Structure of Solutions 24

2.1.4 Water under Hydrothermal Conditions 28

2.2 Acidity and Cation Speciation 30

2.3 Mechanisms of Hydroxylation and Redox Reactions in Solution 36

2.4 Evaluation of Partial Charges on Atoms in Combination 38

2.4.1 Ionocovalency and Partial Charges 39

2.4.2 Electronegativity 39

2.4.3 Partial Charges Model 41

3. Condensation in Solution: Polycations and Polyanions 49

3.1 Hydroxylation and Condensation of Cations 49

3.1.1 Mechanisms and Structural Considerations 50

3.1.2 The Different Behaviors of Cations Against Condensation 55

3.2 Olation: Formation of Polycations 57

3.2.1 Mechanisms and Structural Considerations 57

3.2.2 Chromium III Polycations 61

3.3 Oxolation: Formation of Polyanions 64

3.3.1 Elements of the p-Block 66

3.3.2 Transition Elements under High Oxidation States: Polyoxometalates 72

4. Precipitation: Structures and Mechanisms 107

4.1 The Formation of Solids: Thermodynamics and Crystal Structure 108

4.1.1 Divalent Elements 108

4.1.2 Layered Double Hydroxides 116

4.1.3 Trivalent Elements 119

4.1.4 Tetra- and Pentavalent Elements 124

4.1.5 Transition Elements under High Oxidation States 131

4.1.6 Summary 143

4.1.7 Polymetallic Oxides 143

4.2 Kinetics of Precipitation and Mechanisms of Crystallization 149

4.2.1 The Steps in the Formation of a Solid 150

4.2.2 Nucleation and Growth: Energetics and Dynamics 152

4.2.3 Mechanisms of Crystallization: Structural and Morphological Evolution of Oxide Nanoparticles in Suspension 161

4.2.4 Effect of Microwave Heating on Crystallization in Solution 172

5. Surface Chemistry and Physicochemistry of Oxides 181

5.1 The Oxide–Solution Interface 182

5.1.1 Origin of the Electrostatic Surface Charge 182

5.1.2 Surface Acidity: Multisite Complexation Modeling 184

5.2 Solvation and Structure of the Solid–Solution Interface 191

5.2.1 Solvation of Particles 191

5.2.2 Surface–Electrolyte Interactions 193

5.3 Stability of Nanoparticle Dispersions Against Aggregation 197

5.3.1 Van der Waals Forces 198

5.3.2 Electrostatic Forces 199

5.3.3 Total Potential Energy of the Interaction 199

5.4 Surface Reactivity: Adsorption 202

5.4.1 Electrostatic Interactions, Outer-Sphere Surface Complexes 202

5.4.2 Specific Interactions: Inner-Sphere Surface Complexes 203

5.4.3 Adsorption and Transfers Through the Oxide–Solution Interface 211

5.4.4 Adsorption and Surface Energy: Role of Acidity in Particle Size and Morphology 216

6. Aluminum Oxides: Alumina and Aluminosilicates 227

6.1 Introduction 227

6.2 Hydroxylation and Condensation in Solution: Polycations 228

6.3 Formation of Solid Phases 237

6.3.1 Aluminum Hydroxides, Oxyhydroxides, and Oxides 237

6.3.2 Aluminosilicates 249

7. Iron Oxides: An Example of Structural Versatility 263

7.1 Speciation of Iron and Condensation in Aqueous Solution 265

7.2 Formation of Solid Phases 269

7.2.1 Ferrous Hydroxide and Oxidized Derivatives: Feroxyhyte and Lepidocrocite 269

7.2.2 Ferric Compounds: Ferrihydrite, Goethite, Hematite, Akaganeite 271

7.2.3 Mixed Ferric-Ferrous Phases: Green Rusts and Magnetite 290

7.2.4 Polymetallic Ferrites: Spinels, Hexaferrites, Garnets 308

8. Titanium, Manganese, and Zirconium Dioxides 325

8.1 Speciation of TiIV, MnIV, and ZrIV in Solution 326

8.2 Titanium Oxide 327

8.2.1 Precipitation of Ti4+ Ions in Acidic to Neutral Media 329

8.2.2 Transformation of Layered Titanates 338

8.2.3 Oxidation of TiIII and Ti0 in Acidic to Neutral Medium 343

8.2.4 Synthesis of Barium Titanate BaTiO3 347

8.3 Manganese Oxides 351

8.3.1 The Main Crystal Phases of MnO2 Dioxide 351

8.3.2 Precipitation of Manganese Oxides 353

8.4 Zirconium Oxides 364

8.4.1 The Crystal Varieties of Zirconia 365

8.4.2 Precipitation of Zirconia 365

8.4.3 Synthesis of Stabilized Zirconia 369

Conclusion 383

Index 385

PREFACE

The aim of this book is to present an overview of metal oxide nanoparticle fabrication in aqueous solution. Indeed, nanomaterials generate considerable interest because of their specific behaviors and properties, which have made their use increasingly diversified. Among these nanomaterials, metal oxides hold a special place because of the diversity of their properties.

The synthesis of oxide nanoparticles in allowing the control of their crystal structure, shape, size, and size distribution to optimize their physical properties has long been one of the ultimate goals of colloidal chemistry. This goal is still part of an intense effort, as shown by the huge number of articles published on this subject even to the present day. Of the large variety of synthesis pathways, precipitation in aqueous solution from metal salts is the most common and versatile method for obtaining oxide nanoparticles by sustainable green chemistry corresponding to an ecodesign of materials. Indeed, the technique does not require the use of solvents or ligands that present unwanted effects, even toxic ones. The environmental interest in the technique may consequently be added to the technological interest it has inspired.

This book is intended for students, researchers, and engineers interested in the precipitation of nano-oxides and their surface physical chemistry, not only in the field of materials but also in geochemistry and mineralogy—two fields that are directly and deeply associated with the aqueous chemistry of metal cations.

This book is in fact the second completely revised and extended edition of Metal Oxide Chemistry and Synthesis published in 2000 by John Wiley and Sons. The basic concepts of the chemistry of cations in solution are still valid, but after almost 20 years, immense progress has been achieved: the precipitation of most of the elements has been widely studied; the growth of particles by ordered aggregation (oriented attachment) today represents experimental evidence; theoretical modeling of oxide surface energy and the dynamics of nucleation and growth have been developed; and so on. It therefore became necessary to update the presentation of knowledge in this field, and it is for this reason that I rewrote this book, based on the course I was teaching at the University Pierre and Marie Curie, Paris, France. In the new edition of the book, the first five chapters include the major concepts: specificity of nanostructures, mechanisms of hydroxylation and condensation of cations in solution, structural and kinetic aspects of precipitation, and surface reactivity of oxides. The last three chapters are devoted to the chemistry of some technologically and environmentally important elements, such as aluminum, iron, titanium, manganese, and zirconium.

I warmly thank Philippe Belleville, Corinne Chanéac, David Chiche, Anne Duchateau, Cédric Froidefond, Julien Hernandez, Hanno Kamp, Magali Koelsh, Stéphane Lemonnier, Micaela Nazaraly, Thierry Pagès, Céline Pérégo, Agnès Pottier, David Portehault, Tamar Saison, and Lionel Vayssières, who completed their PhDs under my (co)direction. Their work added considerably to this book.

I am greatly indebted to Elisabeth Tronc, Marc Henry, Corinne Chanéac, Sophie Cassaignon, Olivier Durupthy, and all post–PhD students for the work we achieved together. I hope that in this book they find my expression of gratitude and friendship.

I would also like to thank all my colleagues from the French and foreign academic communities as well as from industry, who, through diverse collaborations or during simple exchanges, contributed closely and even furthered this work. I particularly want to thank Benjamin Gilbert (Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, USA), Alain Manceau (University of Grenoble, France), and Claudine Noguera (University P. & M. Curie, Paris, France) for their advice, suggestions, and exciting discussions.

Finally, I wish to express my gratitude and extend my friendship to Jacques Livage and Clément Sanchez for the high quality of their scientific work and for the happy years we spent together in the laboratory Chimie de la Matière Condensée de Paris.

ABBREVIATIONS

AO atomic orbital

EPR electron paramagnetic resonance

EXAFS extended X-ray absorption fine structure

FESEM field effect scanning electron microscopy

HRTEM high-resolution transmission electron microscopy

IEP isoelectric point

MO molecular orbital

NMR nuclear magnetic resonance

PZC point of zero charge

SAXS small angle X-ray scattering

SEM scanning electron microscopy

TEM transmission electron microscopy

Metal Oxide Nanostructures Chemistry

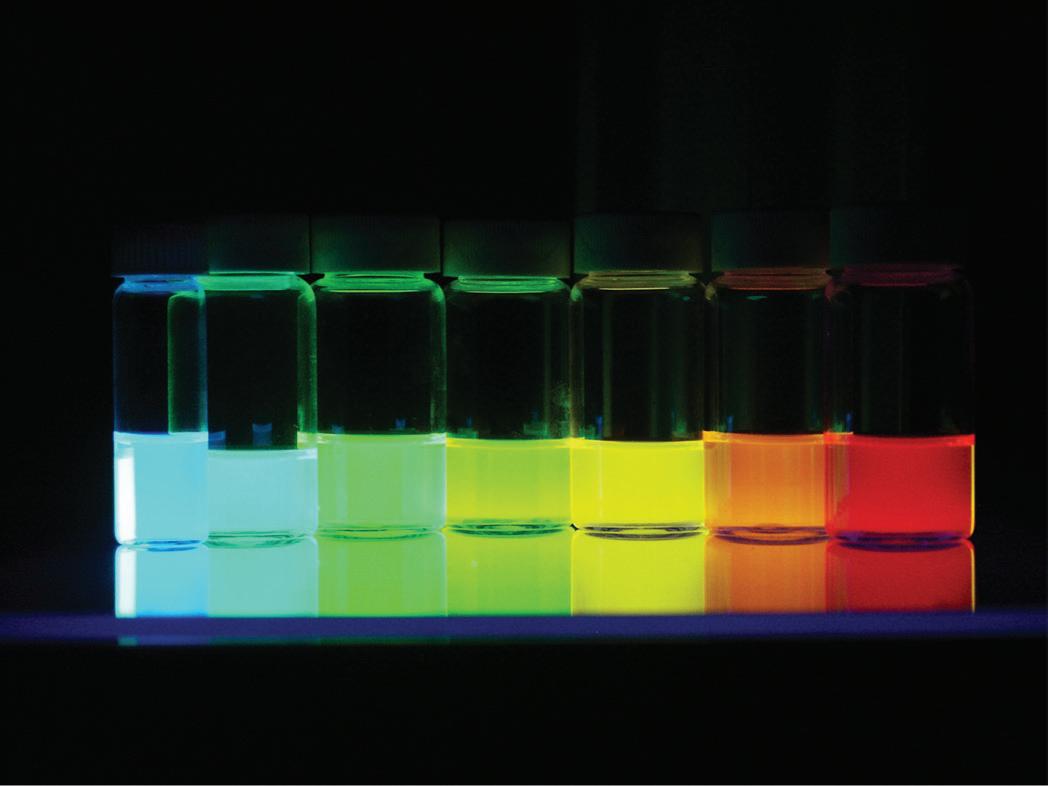

FIGURE 1.1 (c) Light emission under UV irradiation of CdSe nanoparticles dispersed in hexane. The particle size varies from 1.5 nm (blue) to 7 nm (red) (courtesy of B. Dubertret, ESPCI, Paris, France).

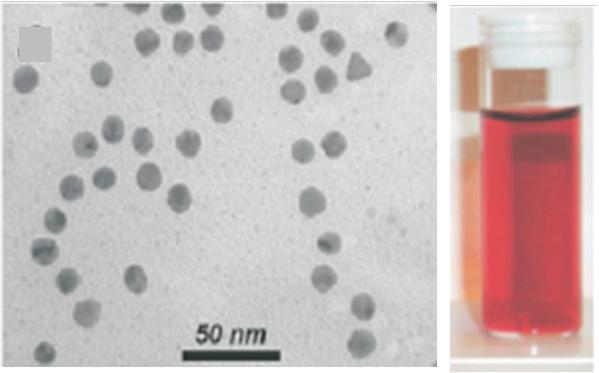

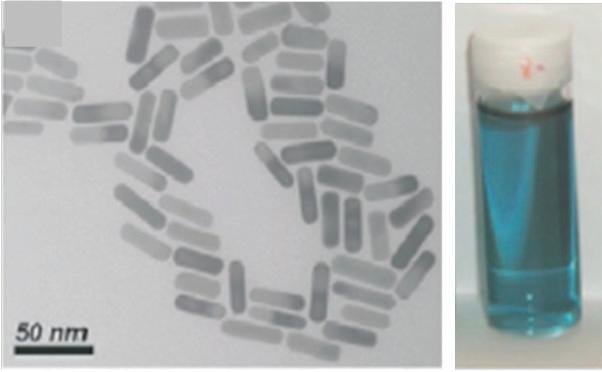

FIGURE 1.2 TEM images of aqueous dispersions of gold nanospheres (a) and nanorods (b) and colors of these dispersions (reproduced from Liz-Marzan L.M., Nanometals: formation and color, Materials Today 2004, 26–31 with permission of Elsevier).

(a)

(b)

FeTdvacancies

FIGURE 1.7 Scheme of adsorption sites for AsIII on nanoparticles 6 nm in diameter based on structural information deduced from X-ray diffraction and As K-edge XAS analyses. (a) Idealized structure of {111} faces of maghemite, γ-Fe2O3 (octahedra and tetrahedra are FeO6 and FeO4, respectively). (b) Nanoparticle exhibiting FeIII vacancies. (c) Filling of the most reactive sites by arsenic at low coverage rate. (d) Adsorption on lattice positions at higher surface coverage allowing a decrease of surface energy.

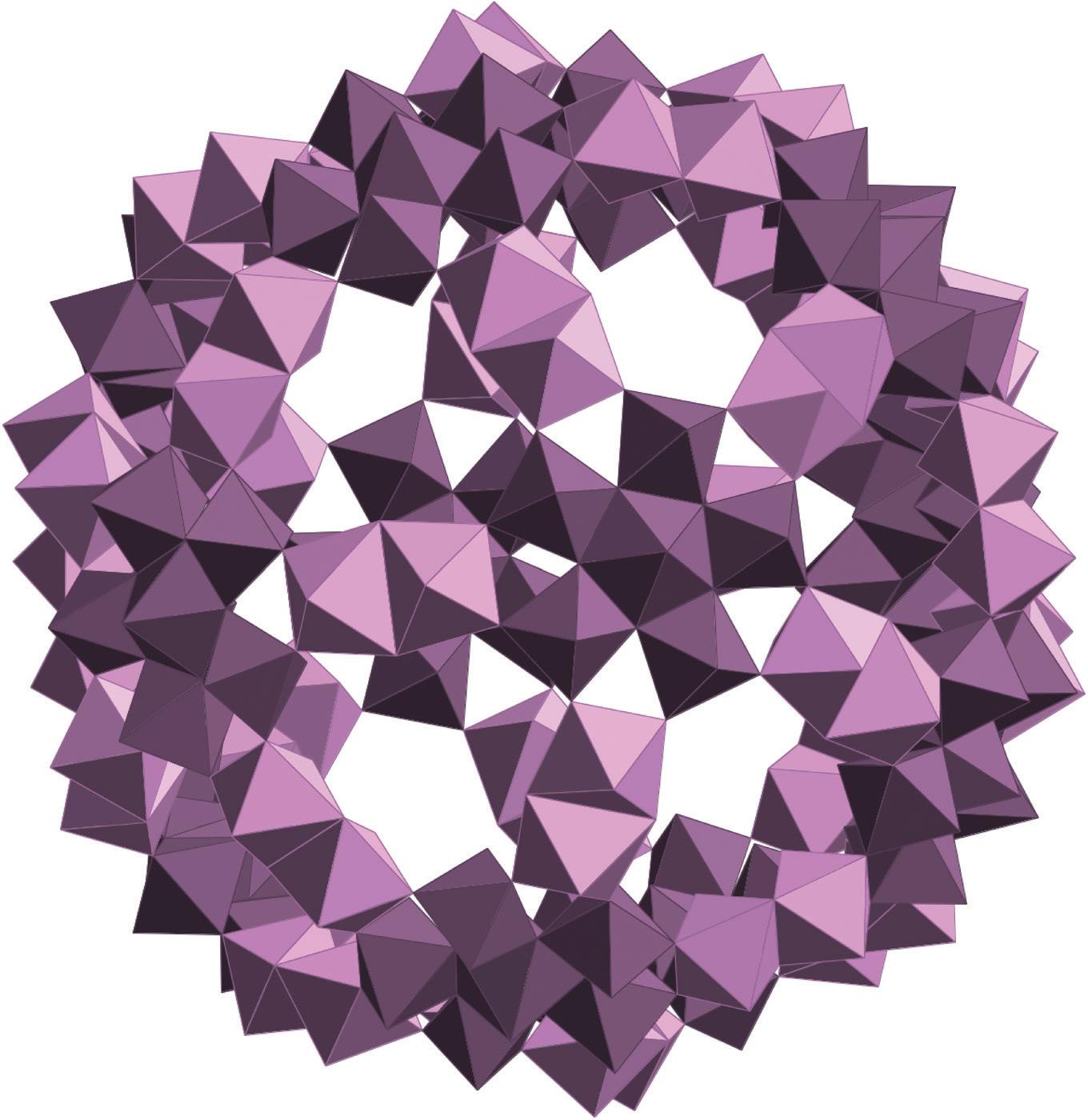

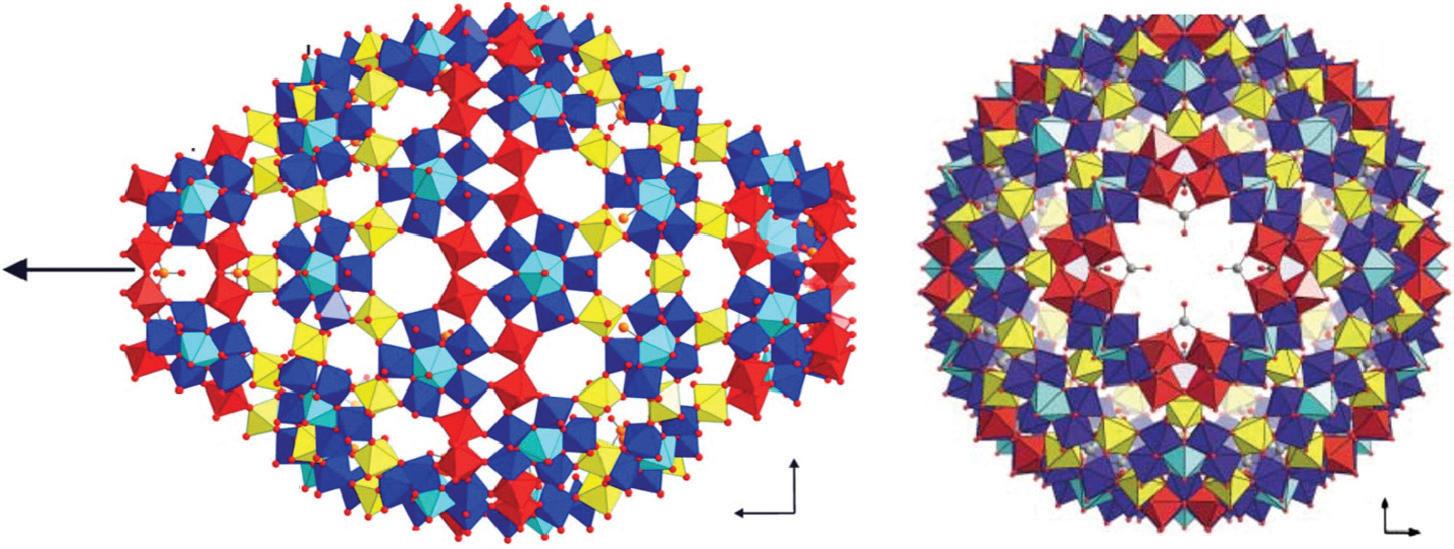

FIGURE 3.37 Scheme of the structure of [Mo132O372(CH3COO)30(H2O)72]42–, including 12 (Mo6) units (dark gray) linked by (Mo2) bridges (light gray).

(a)

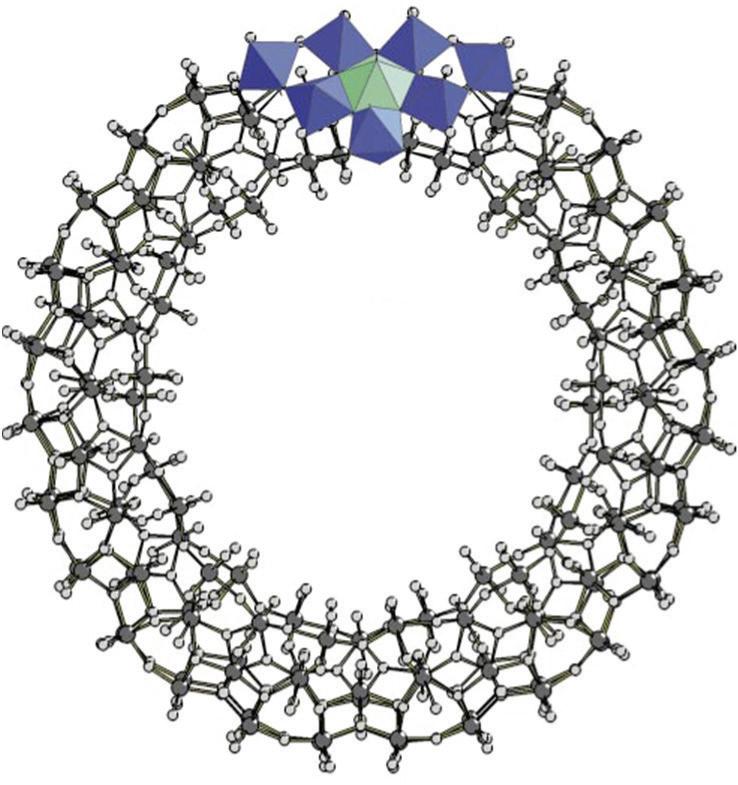

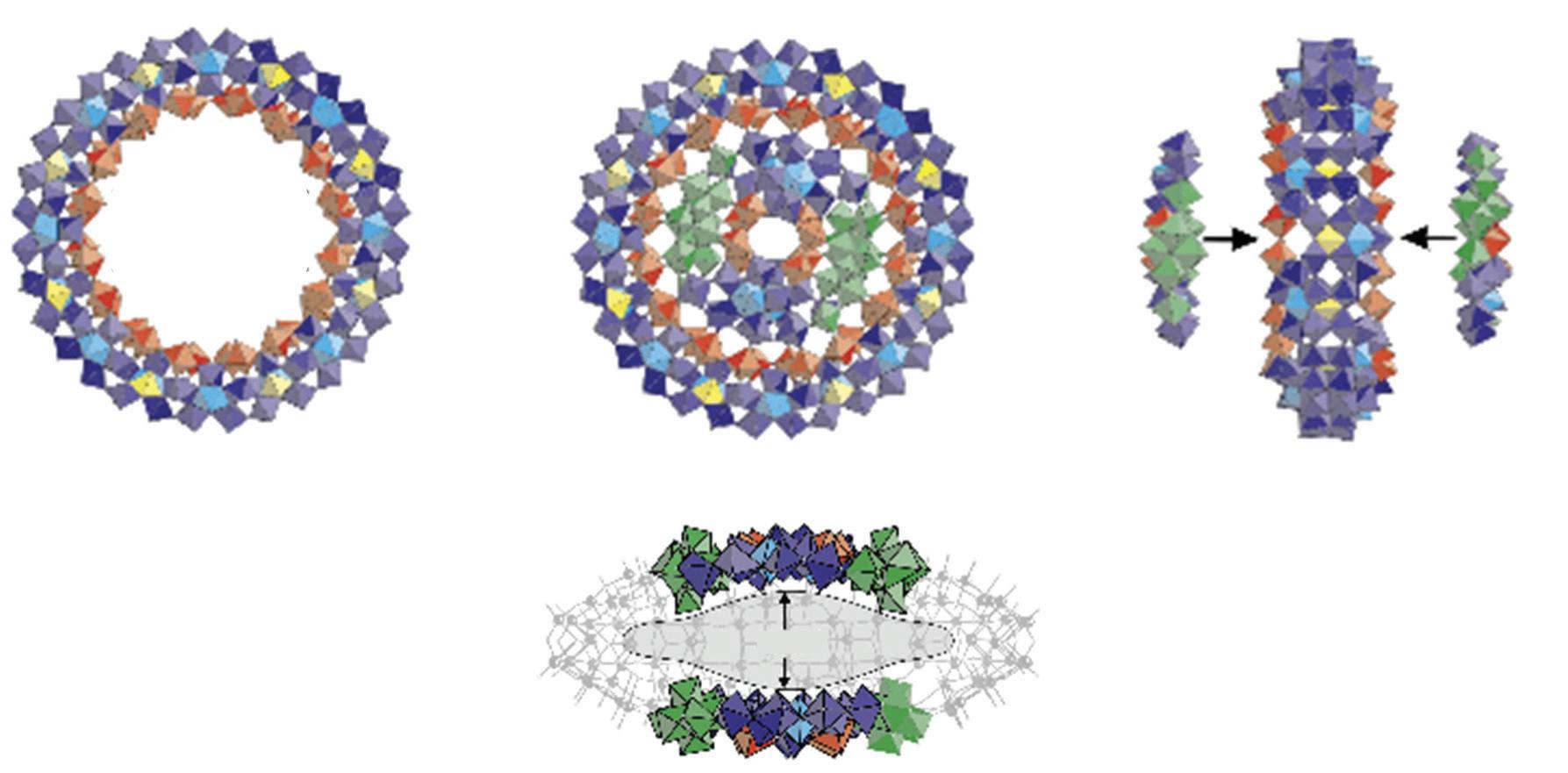

FIGURE 3.38 Scheme of the structure of the (Mo154) wheel. Left, view perpendicular to the C7 axis. Polyhedral representation of a (Mo6) unit with the linkage MoO6 octahedra. Right, polyhedral representation along the C7 axis (reproduced from [Müller A., Kögerler P., Kuhlmann C., A variety of combinatorially linkable units as disposition: from a giant icosahedral keplerate to multi-functional metal–oxide based network structures, Chem. Commun. 1999, 1347–1358] with permission of The Royal Society of Chemistry).

FIGURE 3.39 Schematic view of (Mo176) and (Mo248) (the MoO7 polyhedra are in Turkish blue). View of the cavity in (Mo248) and sketch of the association of the two (Mo36) fragments with (Mo172) (reproduced from [107] with permission of the Nature Publishing Group).

(Mo176)

(Mo36) (Mo36) (Mo176) (Mo248)

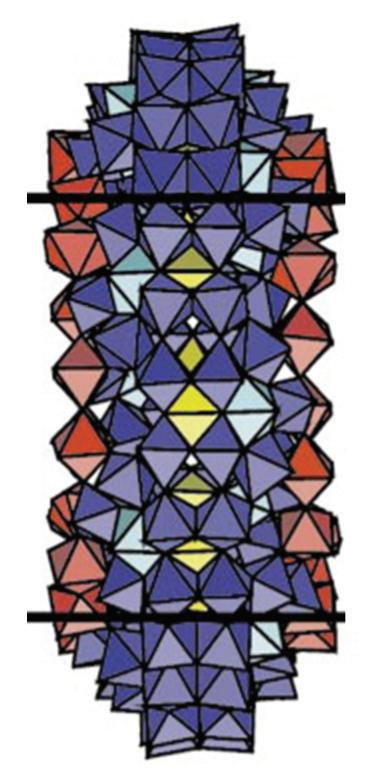

FIGURE 3.40 Scheme of the structure of (Mo368) along th C4 axis. The MoO7 polyhedra are in Turkish blue (reproduced from [101] with permission of Elsevier).

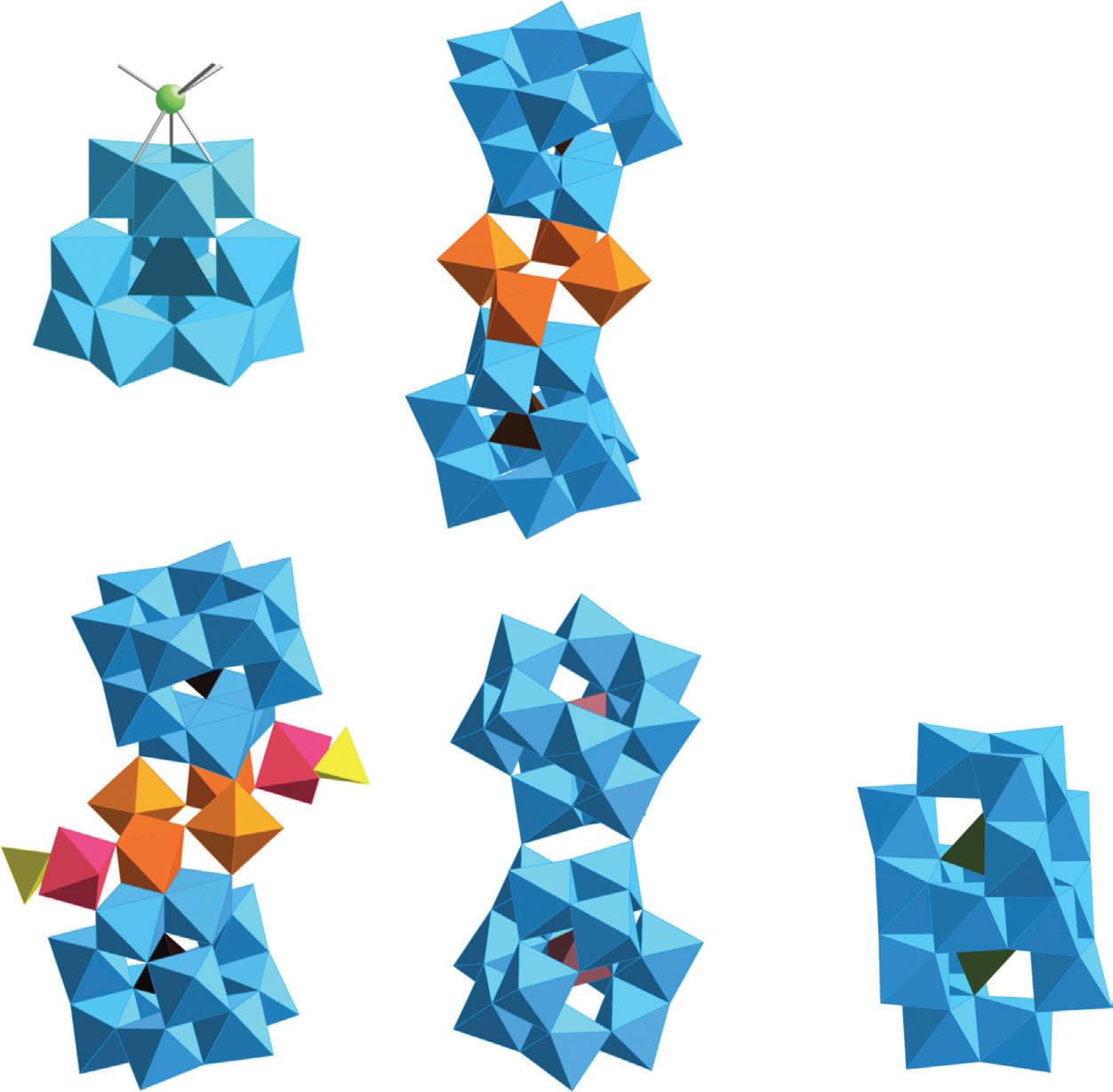

FIGURE 6.5 Structures of (a) Na[Al13O4(OH)24(H2O)12]8+ (δ-Al13) and (b) [Al30O8(OH)56(H2O)24]18+ (Al30); (c) 27Al-NMR spectra of ε-Al13 and Al30 species in solution (reproduced with permission from [22] Copyright 2000 American Chemical Society); (d) 27Al-NMR MAS spectrum of the sulfate salt Al30(SO4)9·xH2O (130.3 MHz, rot 5 kHz) (*rotation peaks) (reproduced with permission from [23] Copyright 2000 American Chemical Society); (e) structure of [Al32O8(OH)60(H2O)28(SO4)2]16+ (Al32); (f) structure of [Al26O8(OH)50(H2O)20]12+ (Al26); (g) structure of [Ga2Al18O8(OH)36(H2O)12]8+ (Ga2Al18).

(g)

Elasticity

∆Ec > 0

∆Ec + ∆Ee < 0

∆Ec + ∆Ee > 0

∆Ee < 0

Electrostatic attraction

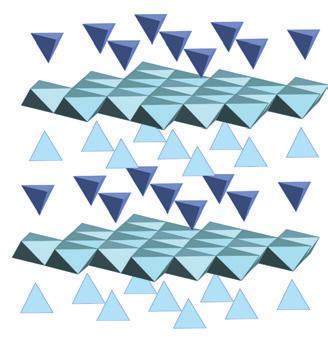

FIGURE 6.29 Schematic sketch for the proto-imogolite transformation into single- or double-wall imogolite nanotubes, depending on the energetic balance between electrostatic interaction and curvature change in the sheet (reproduced with permission from [102] Copyright 2012 American Chemical Society).

FIGURE 7.1 (a) Landscape of Luberon (southwestern France) showing a deposit of ochre (goethite and hematite).

OH/Fetotal

Fe(OH)2

Magnetite, maghemite Fe3O4 γ-Fe2O3

Fe3O4

Hematite α-Fe2O3

Fe2O3

FeO(OH)

FeIII/(FeII+FeIII)

FIGURE 7.2 Main structural types of iron oxy(hydroxi)des as a function of the ferric-ferrous composition FeIII/Fetotal and the hydroxylation ratio OH/Fetotal

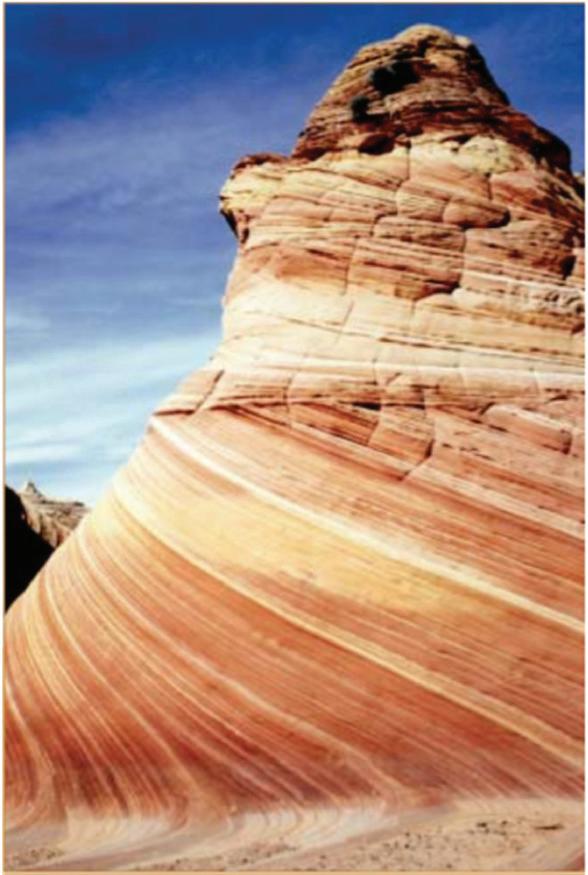

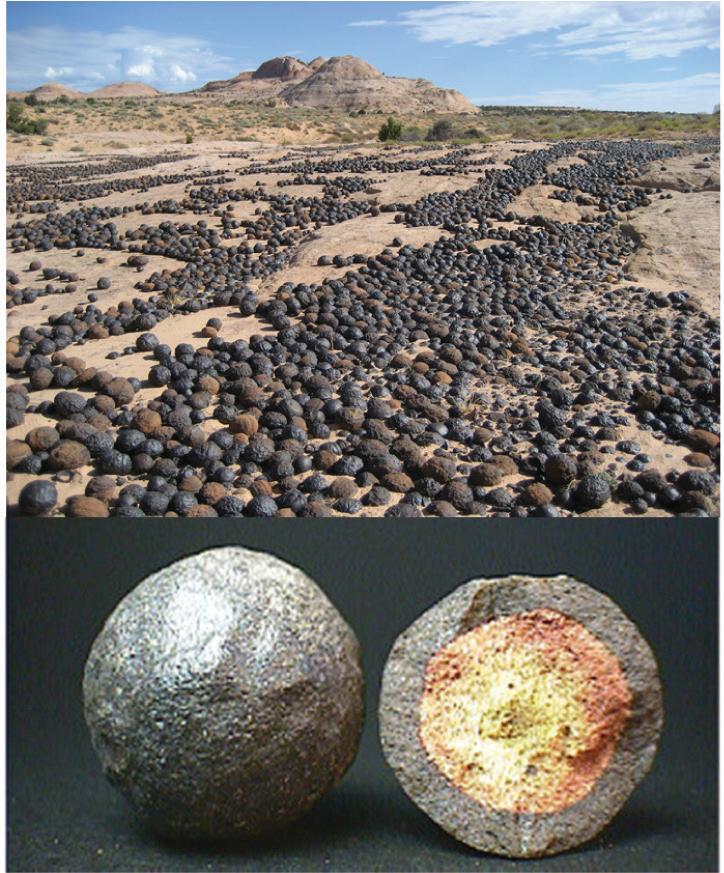

FIGURE 7.12 (a) Coyote Buttes, Paria Wilderness Area, Utah–Arizona border (USA). (b) Overview of moqui marbles in this area (courtesy of M. A. Chan, Univ. of Utah, USA). (c) Cross section of a broken moqui marble (image by Shinishi Kato with permission of rocksandminerals.com).

(a)

(b)

Feroxyhyte δ-FeOOH

Green rust (GR)

Lepidocrocite γ-FeOOH

Goethite α-FeOOH

Akaganeite β-FeOOH

FIGURE 7.33 (a) Soil profile in a forest near Fougères (France). Under the surface overlying an organomineral horizon, the bluish-green fougerite stays in a reductomorphic zone (15–30 cm). Fougerite quickly turns to ochre upon contact with oxygen, after opening the profile (courtesy of Dr F. Trolard, INRA, Avignon, France).

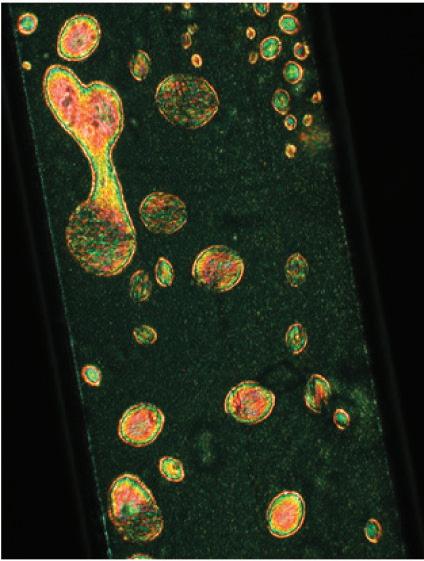

FIGURE 8.13 Images in optical microscopy between cross-polarizing crystals of suspensions of TiO2 rutile particles (mean size 200 × 11 – 15 nm, L/D = 15, pH 2) with volumic fraction ≈ 6% (a), ≈ 10% (b). The colored zones are nematic domains (c) spontaneously formed in the isotropic phase.

(a)

(b)

(c)

[Ti(OH2)6]3+/

[Ti(OH)(OH2)5]2+

pH 1

pH 3

Ti(OH)3/Ti2O3 pH 11 [Ti(OH)2(OH2)4]+

Ti6O11/Ti7O13 pH 9.4 (60 min)

TiO2 pH 9.2 (150 min)

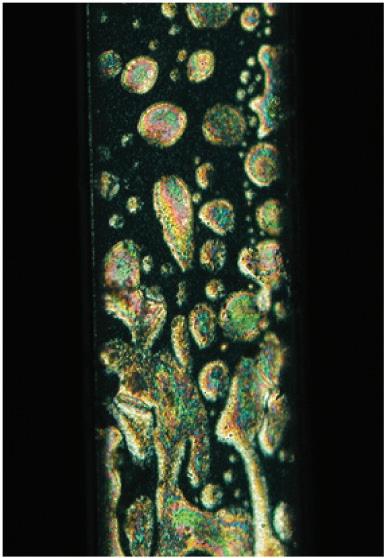

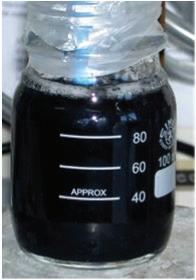

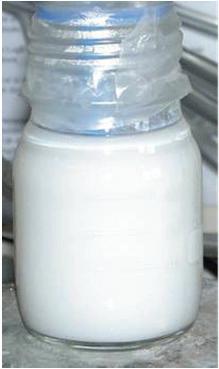

FIGURE 8.26 Titration curve by NaOH of a TiCl3/HCl solution. From the left to right, images and compositions of solutions and suspensions at pH 1, 3, and 11 and suspensions aged at room temperature for 60 and 150 minutes in which the pH is decreasing with oxidation [42].

1 }

Nanomaterials

SPECIFICITIES OF PROPERTIES AND SYNTHESIS

The concept of material concerns matter in solid state that is endowed with usable properties for practical applications. It is indeed in the solid state that matter exhibits the highest mechanical strength and chemical inertness, providing solidity and sustainability because the solid is based on an extended stiff crystalline framework. It is also in the solid state that many properties exist, including optical, electrical, and magnetic properties, providing great technological progress. A typical example is electronics which owes its enormous development to doped silicon. A material may therefore be defined as a useful solid.

The properties of a solid depend directly on its chemical composition, crystalline and electronic structures, texture, as well as morphology and casting. This last point, which is often neglected, is illustrated by amorphous silica glass, which is used largely for its properties such as chemical inertness, mechanical strength, optical transparency, and low thermal and electrical conductivities. These various properties are highlighted through the many possibilities of casting and shaping: flat glass (optical transparency for glazing); hollow glass (chemical inertness and mechanical strength for bottling); short fibers (glass wool for heat insulation) and long fibers (optical fibers); massive pieces (insulators for electric power lines); and thin films (insulating layers for miniaturized electronics).

Metal oxides exhibit a wide range of exploitable properties useful for innumerable applications. Silica, SiO2, as flat glass, has excellent optical properties, but other oxides such as LiNbO3 and KTiOPO4 exhibit interesting nonlinear optical properties, allowing changes in the wavelength of the transmitted light. Certain oxides are good electrical insulators (SiO2), but others are true electronic conductors (VO2, NaxWO3), ionic conductors (β-alumina NaAl11O17, NaSiCON Na3Zr2PSi2O12, yttria-stabilized cubic zirconia Zr1–xYxO2–x/2), and also superconductors (cuprates such as YBa2Cu3O7–x and Bi4Sr3Ca3Cu4O16+x).

Compounds such as BaTiO3, PbZr1–xTixO3, and PbMg1/3Nb2/3O3 are ferroelectric solids used largely as miniaturized electronic components, whereas spinel ferrite γ-Fe2O3, barium hexaferrite BaFe12O19, and garnet Y3Fe5O12 are more or less coercive ferrimagnetic solids used in magnetic recording or as permanent

magnets. Alumina and aluminosilicates (clays and zeolites) are used in many areas as absorbents or catalysts because of their crystalline structure exhibiting interfoliar spaces or channels in which internal diffusion of ionic and molecular species can occur.

In addition to properties due to crystalline structure and chemical composition, some properties are specifically due to or depend on the size and shape of particles in the nanometric range (from 1 to some tens of nanometers). Today, these properties are exploited for multiple uses in many fields, for instance, that of materials: composites, membranes with controlled porosity, reinforcement and ignifugation of polymers, hydrophobic coatings, ferrofluids, and so on; the energy field: including photocells, photocatalytic self-cleaning glazings, and antireflective treatments of mirrors for power lasers; medicine: diagnostic, vectorization, imaging; and the environmental field: catalytic cleanup of Diesel exhaust gases, water nanofiltration, and so forth. Interest in ultradivided matter has recently revealed the concept of nanomaterial. The origin of its peculiarities is briefly studied in the next section.

1.1 Specific Properties of Nanoparticles

For several decades, ultrafine matter has attracted great scientific and technological interest, which has led to the development of nanomaterial sciences. A nanomaterial is defined with regard to the size of its individual components in the nanometric range and the specific properties it exhibits regarding those of the same matter in a bulky state. These specific properties may be a peculiar physics owing to the small volume of matter enclosed in a nanoparticle and/or a chemical reactivity enhanced by the huge surface area developed in nanoparticle assemblies up to some thousand m2.g-1

1.1.1 VOLUME EFFECTS

Small volumes of solid matter exhibit properties that are different from those of massive state (micronic size or more) toward energy-matter interaction involved with light and electric and magnetic fields. The phenomenon occurs when at least one dimension of the object is of the order of magnitude of fundamental physical lengths—for instance, the mean free path of electrons in solid, the wavelength of light or of phonons in solid, as well as the size of magnetic domain. Owing to quantum confinement, specific effects which depend on the size and shape of nanoparticle or crystalline domains are resulting. Such effects, related to nanoscaled solids, have led to the development of various scientific and technical fields such as plasmonics, photonics, spintronics, and nanomagnetism, for which physical laws are now relatively well established [1]. Among the consequences of size effects, the various colors of semiconducting nanoparticle dispersions, such as cadmium and zinc chalcogenides, and of metal nanoparticles, such as gold, silver, and copper, are easily observable.

Cadmium and zinc chalcogenides, CdE, ZnE (E = S, Se, Te), are semiconductors whose optical properties (absorption, fluorescence) strongly depend on size effects because of changes in the electronic structure of the solid. Optical absorption corresponds to electron excitation from the highest occupied level in the valence band toward the lowest empty level in the conduction band (see § 1.1.3c). The difference in energy between these levels (gap) determines the wavelength of absorption and consequently the color of the material because the gap in chalcogenides corresponds to the energy of visible light (Fig. 1.1a). The effect is highlighted by the shift of the light absorption peak toward shorter wavelengths (blue shift) for CdSe nanoparticles of decreasing size (Fig. 1.1b). Fluorescence is the light emission that accompanies the return to the fundamental state of electrons excited beforehand by ultraviolet (UV) light. The color of fluorescence depends on the particle size for the same reason as for absorption (Fig. 1.1c). Beyond about 10 nanometers, the size effect on the electronic structure becomes insignificant.

Gold is a yellow metal, even though it is used as a very thin coating of some micrometers in thickness for gilding, whereas gold nanoparticle dispersions exhibit various colors ranging from red to green or blue. For metallic conductors, the size effect plays on the oscillations of the conduction electron cloud generated by light excitation. It results in a plasmon resonance that modifies the light absorption [2]. The absorbed energy depends on the wavelength according to the following equation [3]:

FIGURE 1.1 (a) Scheme of an electronic structure showing the demultiplication of energy levels with the size of the object and consequently with the number of involved atomic orbitals in bonds. It results in a change in the width of the forbidden band (gap) between the valence band (VB) and the conduction band (CB). (b) Absorption spectra of CdSe nanoparticles dispersed in hexane, with mean sizes from 1.2 to 11.5 nm (reproduced with permission from [42] Copyright 1993 American Chemical Society). (c) Light emission under UV irradiation of CdSe nanoparticles dispersed in hexane. The particle size varies from 1.5 nm (blue) to 7 nm (red) (courtesy of B. Dubertret, ESPCI, Paris, France).