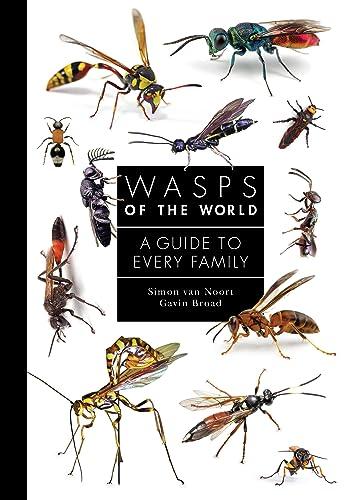

MEREOLOGY

A . J . COTNOIRANDACHILLEC . VARZI

GreatClarendonStreet,Oxford, OX 26 DP , UnitedKingdom

OxfordUniversityPressisadepartmentoftheUniversityofOxford. ItfurtherstheUniversity’sobjectiveofexcellenceinresearch,scholarship, andeducationbypublishingworldwide.Oxfordisaregisteredtrademarkof OxfordUniversityPressintheUKandincertainothercountries

c A.J.CotnoirandAchilleC.Varzi 2021

Themoralrightsoftheauthorshavebeenasserted FirstEditionpublishedin 2021 Impression: 1

Allrightsreserved.Nopartofthispublicationmaybereproduced,storedin aretrievalsystem,ortransmitted,inanyformorbyanymeans,withoutthe priorpermissioninwritingofOxfordUniversityPress,orasexpresslypermitted bylaw,bylicenceorundertermsagreedwiththeappropriatereprographics rightsorganization.Enquiriesconcerningreproductionoutsidethescopeofthe aboveshouldbesenttotheRightsDepartment,OxfordUniversityPress,atthe addressabove

Youmustnotcirculatethisworkinanyotherform andyoumustimposethissameconditiononanyacquirer

PublishedintheUnitedStatesofAmericabyOxfordUniversityPress 198 MadisonAvenue,NewYork,NY 10016,UnitedStatesofAmerica

BritishLibraryCataloguinginPublicationData Dataavailable

LibraryofCongressControlNumber: 2021939306

ISBN 978–0–19–874900–4

DOI: 10 1093/oso/9780198749004 001 0001

PrintedandboundintheUKby TJBooksLimited

LinkstothirdpartywebsitesareprovidedbyOxfordingoodfaithand forinformationonly.Oxforddisclaimsanyresponsibilityforthematerials containedinanythirdpartywebsitereferencedinthiswork.

InmemoryofJoshParsons(1973-2017)

PREFACE

Thisbookhasonepurposeandsomerelated,morespecificaims.Thepurposeistomeetagrowingdemandforasystematicandup-to-datetreatmentofmereology.SincethepublicationofPeterSimons’acclaimedbook, Parts.AStudyinOntology (1987),interestinthisdisciplinehasgrowntremendously.Mereologyisnowacentralfieldofphilosophicalresearch,notonly inontology,butinmetaphysicsmorebroadly,witnessthepublicationof tworecentvolumesofessaysdevotedtomereologicalissuesinthemetaphysicsofidentity(CotnoirandBaxter, 2014)andinthetheoryoflocation (Kleinschmidt, 2014).Mereologicalquestionsandtechniqueshavealsobecomecentralinotherareasofphilosophy,includinglogic,thephilosophyof language,andthefoundationsofmathematics(especiallythanksto Lewis, 1991)aswellasinneighboringdisciplinessuchaslinguisticsandformal semantics(from Moltmann, 1997 to Champollion, 2017)andtheinformation sciences(Guarino etal., 1996; Lambrix, 2000).Eveninthenaturalsciences mereologyhasbecomeanestablishedframeworkwithinwhichtoaddress long-standingfoundationalquestions,forinstanceinphysics,inchemistry, orincertainbranchesofbiology;therecentpublicationofacollectionentitled MereologyandtheSciences (CalosiandGraziani, 2014)isbutonenotable signofthisbroaderinterest.Mostimportantly,however,thisgrowthininterestandapplicationshasbeenaccompaniedbyunprecedenteddevelopments inthestudyofmereologyitself,understoodasafieldoftheoreticalinquiry initsownright,andkeepingtrackofallthefindingsisanever-increasing challenge.InhisreviewofSimons’book,TimothyWilliamsonwrotethat “Parts couldeasilybethestandardbookonmereologyforthenexttwenty orthirtyyears”(Williamson, 1990,p. 210).AndWilliamsonwasnodoubt correct.Aswepassedthethirddecademark,Simons’bookhasservedadmirablyinthisrole.Nonethelessthefieldhasgrowntremendously;and whilefiveothermonographshaveappearedinthemeantime—Massimo Libardi’s Teoriedellepartiedell’intero (1990),AndrzejPietruszczak’s Metame-

xii preface

reologia (2000b)and Podstawyteoriicz ˛ e´sci (2013),LotharRidder’s Mereologie (2002),andGiorgioLando’s Mereology:APhilosophicalIntroduction (2017)— onlyoneofthemisinEnglish* andnonecoversthelatesttechnicaland philosophicaldevelopmentsinasystematicfashion.Thepurposeofthis bookistofillthatgap.

Ourmorespecificaimsarethreefold.First,weaimtoclarifythevarieties offormalsystemsthathavebeenputforwardanddiscussedovertheyears, includingdifferentaxiomatizationsofthetheoryknownas‘classicalmereology’alongwiththemotivationsandmaincriticismsofeachapproach. Second,weaimtocontributetothedevelopmentandsystematizationof new,non-classicalmereologicaltheories,withaneyeontheirpotentialimpactondebatesinrelevantareasofmetaphysics,philosophicallogic,the philosophyoflanguage,andthephilosophyofmathematics.Third,weaim todoallthisinawaythatmightproveusefultoexpertsinthefieldand newcomersalike.Thisisprobablythehardestaimtoachieve,butwehave triedtodosobymakingthetextconciseandself-containedwhileatthe sametimesacrificingverylittleintermsofdetailandaccuracy.Wehave alsotriedtobeasneutralaspossibleinourpresentationofphilosophically controversialmaterial—notbecausewedonothaveviews,orbecauseour personalviewsmaynotcoincide,butbecausewethoughtanon-opinionated treatmentwouldbetterserveourpresentpurposeandaims.Weknowinadvancethateachoftheseaimscanonlybeattainedpartially.Wehopethisis alsotrueofourfailures.

Althoughthebookasawholehasbeenwrittenfromscratch,someparts haveancestorsinmaterialthathaspreviouslyappearedinprint.Inchapter 1,sections 1 2 1 and 1 3 drawslightlyon Gruszczy´nskiandVarzi (2015, §§2–3)andon Varzi (2016,§1),respectively.Inchapter 2,section 2 1 isbased ontheaxiomsystempresentedin CotnoirandVarzi (2019).Inchapter 3,sections 3 1 and 3 2 includesomematerialfrom Cotnoir (2013b)and Cotnoir andBacon (2012),andsection 3 3 1 materialfrom Varzi (2006a, 2016,§2 1). Inchapter 4,section 4 1 3 drawssightlyon Varzi (2016,§3 3),sections 4 3 2 and 4.4 useresultsfrom Varzi (2009)and Cotnoir (2016a),andsections 4.5–4.6 expandon Varzi (2007a,§1.3.4, 2016,§3.4).Inchapter 5,section 5.2.1 and 5.2.3 drawslightlyon Varzi (2016,§4.5)andon Cotnoir (2014b),sections 5.3.3–5.3.4 on Cotnoir (2015),andsection 5.5 on Cotnoir (2014a).Finally,in chapter 6,sections 6 3 1 and 6 3 3 drawon Varzi (2016,§5)andsection 6 3 4 on WeberandCotnoir (2015).Wearethankfultoourco-authorsandtothe editorsandpublishersoftheoriginalsourcesfortheirkindpermissionto reusethismaterialinthepresentform.

* Aswegotopress,anEnglisheditionofPietruszczak’s first bookhasappeared.Wehavemade anefforttoupdateourreferencesaccordingly.Prof.PietruszczakinformsusthatanEnglish translationofhis 2013 bookisalsoscheduled.

preface xiii

Ourfurtherdebtsofgratitudeareextensiveanddeep.Forwrittencommentsontheentiremanuscriptatdifferentstagesofitsdevelopment,our greatestthanksgotoRafałGruszczy´nski,KrisMcDaniel,DavidNicolas, AndrzejPietruszczak,MarcusRossberg,andtwoanonymousrefereesfor OxfordUniversityPress.Moreover,anumberofotherfriendsandcolleagues havehelpedusthinkthroughthisprojectinavarietyofways,directlyor indirectly,andourthanksextendtothemall:SimonaAimar,AndrewArlig, AndrewBacon,RalfBader,DonBaxter,JCBeall,FranzBerto,AriannaBetti, EinarBøhn,AndreaBorghini,MartinaBotti,ClaudioCalosi,RobertoCasati, ColinCaret,DamianoCosta,VincenzoDeRisi,TimElder,HaimGaifman, CodyGilmore,MarionHaemmerli,JoelHamkins,KatherineHawley,Paul Hovda,IngvarJohansson,ShievaKleinschmidt,KathrinKoslicki,Tamar Lando,MatthewLansdell,PaoloMaffezioli,OfraMagidor,WolfgangMann, MassimoMugnai,KevinMulligan,Hans-GeorgNiebergall,DanielNolan, thelateJoshParsons,LauriePaul,GreysonPotter,GrahamPriest,Fred Rickey,MarcusRossberg,JeffRussell,ThomasSattig,KevinScharp,Oliver Seidl,StewartShapiro,AnthonyShiver,TedSider,PeterSimons,Jereon Smid,AlexSkiles,BarrySmith,ReedSolomon,Hsing-chienTsai,Gabriel Uzquiano,PetervanInwagen,ZachWeber,andJanWesterhoff.Wewould alsoliketoexpressaspecialnoteofthankstoourstudentsattheUniversity ofStAndrewsandatColumbiaUniversity,particularlytheparticipantsin theArchéMetaphysicsResearchGroup,whoprovideddetailedfeedbackon theveryfirstdraftofthemanuscript(Spring 2016),andtheparticipantsina graduateMereologyseminarheldatColumbia,whodidthesameonalater draft(Fall 2017).AndmanyspecialthankstoPeterMomtchiloffatthePress, bothforhishelpandwarmencouragementandforhispatiencethroughall thephasesoftheproject.Finally,wearedeeplygratefultoourfamilies. Withouttheirunceasingandlovingsupport,theprojectwouldneverhave beencompleted,orevenstarted.

Thepreparationofthebookhasbenefitedfromfinancialsupportfromthe ArchéResearchCentreattheUniversityofStAndrews,froma 2017–2018 LeverhulmeResearchFellowshipfromtheLeverhulmeTrust,andfroma 2019–2020 sabbaticalleavefromColumbiaUniversityandaFellowshipat theWissenschaftskollegzuBerlin,whichweacknowledgemostgratefully.

note Forconvenientreference,alllabeledformulascorrespondingtodefinitions,axioms,andtheoremsofmereologicaltheoriesdiscussedinthetext arereproducedina list attheendofthevolume.Intheelectronicedition, thelabelsofsuchformulas,whencitedinthetext,appearasactivehyperlinkstothelocationswheretheformulasthemselvesarefirstintroduced.

LISTOFFIGURES

2

3

3

3

4 3 AmodelofRemainderwithmissingcomplements

4 4 Acasewhereneither a nor a amountsto a∗

4 5 AmodelofStrongComplementation∗ withmissingremainders

4.6 AmodelofStrongSupplementatiomwithmissingremainders

4.7 AmodelofWeakSupplementationwithoutstrongsupplements

4.8 AmodelofStrictSupplementationwithoutweaksupplements

4.9 AfailureofWeakCompany

4 10 AmodelofWeakCompany

4 14 TwomodelsofQuasi-Supplementation

xvi listoffigures

5.2 F-typefusionsbutno F -typeor F -typefusions 163

5.3 F -typefusionsbutno F-typeor F -typefusions 166

5 4 F -typefusionsbutno F-typefusions 169

5 5 Relationshipsbetweentypesoffusion 173

5 6 Distinctfusionsofdifferenttypes 173

5 7 Commonupperboundsandunderlapwithmissingfusions 186

5 8 Uniquenessof F-typefusionsversus PP -Extensionality 190

5 9 PP -Extensionalitywithout F -typeand F -typeuniqueness 191

5 10 F-typeand F -typefusionsviolatingCAI 195

5.11 AmodelviolatingAssociativity 204

5.12 Atomsthatare(solid)coatoms 222

5.13 Aninfinitelyascendingcoatomisticmodel 223

6.1 Objectswithindeterminateparts 264

6 2 Partsandnon-parts 276

6 3 Universalobjectswithdistinctnon-parts 277

WHATISMEREOLOGY?

Wholeandpart—partlyconcreteparts andpartlyabstractparts—areatthebottomofeverything. Theyaremostfundamentalinourconceptualsystem.

—KurtGödel(reportedin Wang, 1996,p. 295)

Mereology(fromtheGreek μέρος,meaning‘share’,or‘part’)isconcerned withthestudyofparthoodrelationships:relationshipsofparttowholeand ofparttopartwithinacommonwhole.Thetermitselfwasoriginallycoined inthelastcenturybythePolishlogicianStanisławLe´sniewskitodesignate aspecifictheoryofsuchrelationships,correspondingtothethirdcomponentoftheformalsystemwithwhichheaimedtoprovideacomprehensive foundationforlogicandmathematics1 (theothercomponentsbeingdevoted toageneralizedtheoryofpropositionsandtheirfunctions,orProtothetic, andtothelogicofnamesandfunctors,orOntology).2 Today,however,itis commonpracticetospeakofmereologywithreferencetoanytheoryofparthood,andmoregenerallytothebroadfieldofinquirywithinwhichsuch theoriesoriginate,andinthisbookweshallfollowsuit.Infact,Le´sniewski’s owntheoryturnedouttobeenormouslyinfluentialandwilloccupyusa greatdeal,atleastinsofarasitcanbeisolatedfromtherestofhissystem, butitisbynomeanstheonlyone.Moreimportantly,itcertainlydoesnot epitomizetheonlywayofdoingmereology.Toseewhy,andtobetterappreciatethemeaningandscopeofmereologyasweshallunderstandithere,it willbeinstructivetobeginwithabrieflookatthehistoryofthesubject.

1 See Le´sniewski (1927–1931),p. 166 ofpart i;thePolishwordis mereologia.As Simons (1997a, fn. 4)notes,thetermwasprobablychosenbyLe´sniewskiasavariantof‘merology’(merologia),whichwasalreadyinusetoindicatethefieldofanatomydealingwithelementaltissues andbodyfluids(see Robin, 1851,p. 16 fortheoriginalFrenchcoinage, mérologie,and Dunglison, 1857,p. 586 fortheEnglishconversion).Following Hutchinson (1978,pp. 214ff),today ‘merology’isalsousedfortheschoolofecologicalthoughtthatseekstoexplainhigherlevels oforganizationintermsofindividualorganisms(incontrasttothe‘holological’school,which focusesinsteadontheflowofenergyandmaterialsatthelevelofecosystems).

2 LogicallyPrototheticcomesfirst,followedbyOntologyandthenMereology,thoughLe´sniewskiworkedoutthethreecomponentsinreverseorder.Foroverviewsoftheoverallsystem,see Kearns (1967), Rickey (1977), Clay (1980),and Simons (2009a, 2015);forextensivestudies,see Luschei (1962), Miéville (1984), Urbaniak (2014a),andtheessaysin SrzednickiandStachniak (1984)(onProtothetic)and SrzednickiandRickey (1984)(onOntology).

2whatismereology ?

1.1abitofhistory

Asageneralfieldofinquiry,mereologyisactuallyasoldasphilosophy.AlreadyamongthePresocratics,metaphysicalandcosmologicalcontroversies focusedtoagreatextentonthepart-wholestructureoftheworld,andsome ofthemainschoolsofthoughtmaybeseenasdisagreeingpreciselyona mereologicalquestion,namely,whethereverything,something,ornothing hasparts.Thus,theEleaticsheldthatBeingisauniform,‘undividedwhole’ (Parmenides)andthattheverythoughtthattheremaybefurtherparts,spatialortemporal,wouldleadtoparadox(Zeno);theAtomistsmaintained thatsomethingshaveparts,thoughalldivisionmustcometoanend:at bottomtheremustbealayerofpartlessthings,oratoms(literally:‘indivisibles’),outofwhicheverythingelseiscomposed(Democritus);andsome Pluralistswentasfarasclaimingthatallthings,nomatterwhatsize,divide foreverintosmallerandsmallerparts(Anaxagoras).Similarconcernswere centralalsotootherancienttraditions.Thepluralistview,forinstance,prevailedamongtheMíngjia,theChineseschooloflogiciansledbyHuìShı andGongsunLóng,whereastheatomisticstancewasprominentinIndian philosophy,withtheVai´sesikacosmologyofKan . adarelyingonatomsof differentelementalkindsandtheJainschoolchampioningaconceptionof theworldasconsistingwhollyofatoms,orParaman . us,ofjustonesort, exceptforsouls.

IntheWesterntradition,metaphysicalanalysesintermsofpartsand wholescontinuetofigureprominentlybothinthewritingsofPlato(especially Parmenides, Theaetetus,and Timaeus)andinthoseofAristotle(most notablyinthe Metaphysics,wherethehylomorphictheoryofsubstancesis presented,butalsothroughouthislogicalandnaturalphilosophicaltreatises,suchasthe Topics,the Physics,and Departibusanimalium,andevenhis ethicaltreatises).InHellenistictimes,too,theEpicureanandStoicschools reliedonclaimsaboutthekindsofpartsandwholesthatexistinorderto framesomeoftheircentraltheses,ortochallengetheviewsoftheiropponents.Chrysippus,forexample,devotedoneofhisbookstowhatcameto beknownasthe‘growingparadox’,whichhetookfromEpicharmus:how cansomethinggainorlosepartsovertimewithoutceasingtobethethingit is?Similarly,weknowfromPlutarch’s Lives thatthequestionofmereologicalchangewasamplydiscussedinconnectionwiththepuzzleoftheshipof Theseus—theshipofthemythicalkingofAthensthatwaspreserveddown tothetimeofDemetriusPhalereusbyconstantlyreplacingtheold,decayingpartswithnewandstrongertimber.(And,again,thiswasnotaquestion exclusivetoWesternphilosophy.Accordingtothe NihonShoki,forinstance, theGrandShrineofIsewasestablishedbythedaughteroftheJapanese emperorSuininpreciselypursuanttotheShintobeliefsconcerningtheim-

1 1abitofhistory3

permanenceofallthings,withthetwomaintemplesbeingtakenapartand rebuiltonadjacentsiteseverytwentyyears.)

Theinterestinmereologycontinuesthroughoutantiquity,asevidenced e.g.byNeoplatonistthinkerssuchasPlotinus,Proclus,andPhiloponus,and especiallyBoethius,whoplayedacrucialroleintransmittingancientviews onthesematterstotheMiddleAgesthroughhistreatises Dedivisione and InCiceronisTopica.Amongmedievalphilosophers,mereologicalquestions weretakenupextensively,forinstance,byGarlandtheComputistandby PeterAbelard,andeventuallybyallthemajorScholastics:WilliamofSherwood,PeterofSpain,ThomasAquinas,RamonLlull,JohnDunsScotus,WalterBurley,WilliamofOckham,AdamdeWodeham,JeanBuridan,Albert ofSaxony,andPaulofVenice,whosemonumentaltreatiseon‘allpossible logic’,the Logicamagna (1397–1398),containedamplesectionsdevotedexpresslytovariousformsofpart-wholereasoning.

Mereologicalquestionsoccupyaprominentplacealsoinmodernphilosophy,fromJungius’ LogicaHamburgensis (1638)andCavendish’s Opinions (1655)throughLeibniz’s Deartecombinatoria (1666)and Monadology (1714) (andmanyshorteressaysinbetween)toWolff’s Ontologia (1730).Among theEmpiricists,theyarecentrale.g.tothedebateoninfinitedivisibility,witnessHume’sargumentsinthe Treatise (1739)andinthe Enquiry (1748).And, ofcourse,wefindmereologicalconcernsinKant,fromtheearlywritings (e.g.the Monadologiaphysica of 1756)tothefamousSecondAntinomyin the CritiqueofPureReason (1781–1787).Thesis:Everycompositesubstanceis madeupofsimpleparts,andnothinganywhereexistssavethesimpleor whatiscomposedofthesimple.Anti-thesis:Nocompositethingismade upofsimpleparts,andtherenowhereexistsintheworldanythingsimple. Withallthis,itisnotanexaggerationtosaythatmereologicaltheorizing formsacentralchapterofphilosophythroughoutitshistory.3 Nonetheless itshouldbenotedthatsuchextensivetheorizingfocusedbyandlargeon substantivetreatmentsofmetaphysicalquestionsconcerningtheactualpartwholestructureoftheworld.Fewphilosophersengagedinthesystematic studyofpart-wholerelations assuch,asifthepropertiesofsuchrelations wereinsomesenseobvious,oreasilyrecoverable.Forexample,itisnatural toconsiderwhetherparthoodbehavestransitively,sothatthepartsofa

3 Forafullerpicture,see Kaulbach etal. (1974), BurkhardtandDufour (1991),andthehistorical entriesin Burkhardt etal. (2017).Onancienttheories,especiallyPlato’sandAristotle’s,seealso Bogaard (1979), Barnes (1988), Harte (2002), Koslicki (2006, 2008),and Arci (2012).Onmedieval mereology,see Henry (1989, 1991a), Arlig (2011a,b, 2019), NormoreandBrown (2014),andthe essaysin KlimaandHall (2018)and Amerini etal. (2019).Onmodernviews,see Costa (inpress) alongwith Peterman (2019)onCavendish; Schmidt (1971), BurkhardtandDegen (1990), Cook (2000), Hartz (2006),and Mugnai (2019)onLeibniz; FavarettiCamposampiero (2019a,b)on Wolff;and Baxter (1988c), Jacquette (1996),and Holden (2002)onHume.OnKant,see Bell (2001)togetherwith VanCleve (1981), Engelhard (2005), Marschall (2019),and Watt (2019).

4whatismereology ?

wholealwaysincludethepartsofitsparts.Yetitishardtofindanywhere anexplicitdiscussionofthisgeneralprinciple,oroftheconditionsunder whichitholds.Aristotle,forone,seemstoendorseitwhenhesaysthat “whiteisinmanbecauseitisinbody,andinbodybecauseitresidesinthe visiblesurface”(Physics, iv, 3, 210b4–5; Aristotle, 1984,p. 358),andsome ancientcommentatorsreinforcethisview—forinstance,Simplicius: Hesaysthat[...] somethingcanbeinsomethingasapartisinawhole,likea fingerinahandorinthewholebody,inthehandasapartandinthewholebody asapartofapart.(OnAristotle’sPhysics, 551 19–20; Simplicius, 1992,p. 45) 4

Ontheotherhand,Aristotlerecognizesseveralsensesof‘part’,including asenseinwhich“thegenusiscalledapartofthespecies”andanother inwhich“thespeciesispartofthegenus”(Metaphysics, v, 25, 1023b18–25; Aristotle, 1984,p. 1616),anditisnotclearwhetherthecorrespondingparthoodrelationobeysthesamelawsineachcase,oracrosscases.Ifanindividualsubstanceincludesitsformamongitsparts,andtheforminturn includesthegenus,doesitfollowthatSocrates,whoispartofthespecies humanbeing,whichispartofthegenusanimal,whichispartofCoriscus’ form,ishimselfinsomesensepartofCoriscus?5 Andwhatoftransitivity itself—mayitbesaidtoholdinonesensebutnotinanother,evenwithin thesamedomainofapplication,asinthefollowingpassagefromBoethius?

Theletters,syllables,namesandversesareinsomesensepartsofthewholebook. Nevertheless,whentakeninanothermanner,theyarenotpartsofthewhole, rathertheyarepartsofparts.(Dedivisione, 888b; Boethius, 1998,p. 40)

Thisisjustanillustration,butitisindicativeofapatternthatistypicalof mereologicaldiscussionsthroughouthistory.Wearegivensomeexamples, andinferencesaredrawntherefrom,butexactlywhatpart-wholeprinciples thoseinferencesaresupposedtoinstantiateisgenerallyleftinthedark.

OneexceptiontothislackofsystematictreatmentswasLeibniz,whoexplicitlyformulatedasetofgenerallawsinhisessaysonso-called‘realaddition’.Agoodexampleisashortuntitledtextfromaround 1690,which beginswithaformulationofhisfamousIdentityLaw(“Sameorcoincident arethosetermsthatcanbesubstitutedforeachotheranywhere salvaveritate”)andcontinuesbyintroducingabinaryoperationofcomposition, , whichLeibnizaxiomatizesasbeingbothcommutative(B N = N B)and idempotent(A A = A).Fromthis,Leibnizinfers—correctly6 —thatthecor-

4 Thisisstillalimitedthesis.Somescholars(e.g. Barnes, 1988,§2)actuallydoubtanyoneinantiquityeverheldthetransitivityofparthoodinitsgeneralform.

5 Thepuzzleisraisedin Koslicki (2007,pp. 138f; 2008,p. 158).Whetherformsarethemselves parts,however,iscontroversial;seee.g. Galluzzo (2018), Rotkale (2018),and Shields (2019).

6 Usingalsoassociativity,i.e., A (B N)=(A B) N,whichLeibniztakesforgranted.

1 2contemporaryperspectives5

respondingrelationofmereologicalcontainmentis,notonlytransitive,but alsoreflexiveandantisymmetric,whichistosayapartialorder:

‘B N = L’meansthat B isin L,or,that L contains B,andthat B and N together constituteorcompose L [...]

Proposition 7. A isin A [...]

Proposition 15.If A isin B and B isin C,then A isin C [...]

Proposition 17.If A isin B and B isin A,then A = B.(Leibniz, 1966,pp. 132–136)

AnotherimportantprinciplelistedbyLeibnizisthefollowing,whichhe addstothebasicaxiomson .ItsuggeststhatLeibnizregardedmereologicalcompositionasastructuraloperationthatobtainsautomaticallyassoon asseveralthingsareposited,regardlessofwhattheyare:7

Postulate 2.Anypluralityofthings,suchas A and B,canbetakentogetherto composeonething, A B.(ibid.,p. 132)8

Whetherornottheseprinciplesshouldholdunrestrictedlymay,ofcourse, beamatterofcontroversy.Butitispreciselyonprinciplesofthissortthata robustmereologicaltheoryneedstorest.IndeedweshallseethatLeibniz’s intuitionshereareprettymuchinlinewiththoseofmostcontemporary theorists.Unfortunately,however,theywereanisolatedepisode.Leibniz’s foraysintoageneraltheoryofparthoodhadnoimpactwhatsoeveronwhat cameafter,ifanythingbecausetheessaysinquestionwerenotpublished until 1890,andeventhenasminorwritingswithnoapparentconnection withthemostimportantpartsofhisextensivephilosophicalproduction.9

1.2contemporaryperspectives

Thislackofasystematicstudyofthepart-wholerelation perse wasovercomeonlyatthebeginningofthe 20thcentury.Thereweretwomajorimpulsestowardsthischangeofperspective.Onecamefromtheschoolof

7 Cf.thefollowingpassage,fromanearlierfragmentdatingmid-1685: Ifwhenseveralthingsareposited,bythatveryfactsomeunityisimmediatelyunderstood tobeposited,thentheformerarecalled parts,thelattera whole.Norisitevennecessarythat theyexistatthesametime,oratthesameplace.[...] ThusfromalltheRomanemperors together,weconstructoneaggregate.(Leibniz, 2002,p. 271)

8 Herethe 1966 Englishtranslation(byG.H.R.Parkinson)has‘term’insteadof‘thing’.However, intheLatinoriginalitseemsclearthatLeibnizisusingtheneuter,singularorplural,tospeak ofgenericthings(“Pluraquæcunqueut A, B...”),sowefollow Mugnai (2019,p. 55).

9 TheuntitledessaycitedaboveappearedforthefirsttimeinGerhardt’seditionofthe PhilosophischenSchriften (Leibniz, 1890,pp. 236–247),alongwithanothershortessayonthesamesubject entitled Noninelegansspecimendemonstrandiinabstractis (pp. 228–235).Otherrelevantessays werepublishedonlyinCouturat’slatercollection(Leibniz, 1903).FordetailedstudiesofLeibniz’scalculus,see Swoyer (1994), Lenzen (2000, 2004),and,again, Mugnai (2019).

6whatismereology ?

FranzBrentano(whoemphaticallymaintainedthattheproblemsofAristotle’stheoryofcategorieshadtheiroriginsintheunderlyingmereology)10 throughEdmundHusserl;theothercamefromLe´sniewski.11 Theirspecific motivationsweredifferent:inHusserl’scase,thetheoryofpartsandwholes waspivotaltothedevelopmentofageneralframeworkfor formalontology; Le´sniewski’smereology,bycontrast,issuedprimarilyfromhis austerenominalism,andspecificallyfromtheneedofanominalisticallyacceptablealternativetosettheory.Neitherofthesemotivationsisbyitselfintrinsicto mereologyassuch.Nonethelessitispreciselythesetwosortsofmotivations that,together,havefixedthecoordinatesofmostlaterdevelopments.

1 2 1 MereologyasFormalOntology

Husserl’sconceptionofmereologyasapieceofformalontologyreceives itsfullestformulationinthethirdofhis LogicalInvestigations (1900–1901). Broadlyspeaking,thegoalofthisInvestigationwasthedevelopmentof the pure(apriori)theoryofobjectsassuch,inwhichwedealwithideaspertinent tothe categoryofobject [...]aswellasthe apriori truthswhichrelatetothese. (Husserl, 1900–1901,p. 435)

Husserlmentionedseveralother‘ideas’besidesPartandWhole,includingGenusandSpecies,SubjectandQuality,RelationandCollection,Unity, Number,Magnitude,etc.YetthebulkoftheInvestigationisdevotedtothe firstoftheseideasandthetitleitself,‘OntheTheoryofWholesandParts’, spotlightsthecentralityofthepart-wholerelationinHusserl’sproject. Theverynotionofan‘objectassuch’is,ofcourse,heavilyladenwith philosophicalmeaning,asisHusserl’snotionofan apriori truth.Forour purposes,however,thecentralideacanbeputrathersimplyasfollows. Don’tthinkofontologyinQuineanterms,i.e.,asatheoryaimedatdrawing upaninventoryoftheworld,acatalogueofthoseentitiesthatmustexistin orderforourbesttheoriesabouttheworldtobetrue(Quine, 1948).Rather, thinkofontologyintheoldsense,asatheoryofbeing qua being(Aristotle), orperhapsofthepossible qua possible(Wolff).Inthissense,thetaskofontologyisnottofindoutwhatthereis;itistolaybaretheformalstructure ofwhatthereis nomatterwhatitis.Regardlessofwhetherourinventoryof theworldincludesobjectsalongwithevents,concreteentitiesalongwith abstractones,andsoon,itmustexhibitsomegeneralfeaturesandobey somegenerallaws,andthetaskofontology—understoodformally—isto

10 See Brentano (1933,pt. 2,§i).OnBrentano’sviewsonmereology,see BaumgartnerandSimons (1993), Baumgartner (2013), Salice (2017),and Kriegel (2018a,§1 6; 2018b,§3).

11 Le´sniewskididhisdoctoralstudiesunderKazimierzTwardowski,himselfapupilofBrentano andanearlymereologist(see Twardowski, 1894,§§ 9–11).Forconnections,see Rosiak (1998a).

1 2contemporaryperspectives7

figureoutsuchfeaturesandlaws.Forinstance,itwouldpertaintothetask offormalontologytoassertthateveryentity,nomatterwhatitis,isgovernedbycertainlawsconcerningidentity,suchastransitivity:

If x isidenticalto y and y isidenticalto z,then x isidenticalto z.

Ideally,thetruthofthislawdoesnotdependonwhat(kindsof)entitiesare assignedtotheindividualvariables‘x’,‘y’,and‘z’,exactlyasthetruthofthe followinglawconcerningentailmentdoesnotdependonwhatpropositions areassignedtothesententialvariables‘p’,‘q’,and‘r’:

If p entails q and q entails r,then p entails r.

Bothlawsaremeanttopossessthesamesortofgeneralityandtopic-neutrality.Botharemeanttoholdasamatterofnecessityandshouldbediscovered,insomesense, apriori.Andjustasthelatterlawmaybesaidto pertaintoformallogicinsofarastherelevantvariablesrangeoverpropositions,i.e., claimsabout theworld(nomatterwhattheysay),theformerwould pertaintoformalontologyinsofarastheirvariablesrangeover thingsin the world(nomatterwhattheyare).12

Now,Husserl’sviewwasthatthegeneralprinciplesofmereologyshould constituteaformalontologicaltheorypreciselyinthissense,liketheformalprinciplesgoverningidentity.Transitivity,forexample,wouldholdin thesameway:nomatterwhat x, y,and z happentobe,if x ispartof y and y ispartof z,then x mustbepartof z.Andwhatgoesfortransitivity goesforanyothermereologicalprinciplethatatheoryofthissortshould contain.Husserlhimselfdidnotgoasfarasprovidingafullaccount,describingthelawsputforwardinhisInvestigationas“mereindicationsofa futuretreatment”(p. 484).Moreover,suchindicationsarepresentedinaway thatmakesitdifficulttodisentangletheanalysisofthepart-wholerelation fromthatofotherontologicallyrelevantrelations(suchasfoundation).13 Husserl’sconcludingremarks,however,leavenodoubtsastothenature andscopeofthetask.Itisworthquotingtheminfull,fortheyrepresentthe firstexplicitstatementofafull-fledgedprojectinmereology:

Aproperworkingoutofthepuretheoryweherehaveinmindwouldhavetodefineallconceptswithmathematicalexactnessandtodeducealltheoremsby argu-

12 IntheProlegomenatothe Investigations,Husserlspeaksoftheselawsasgoverningthe‘interconnectionsoftruths’andthe‘interconnectionsofthings’,respectively(§ 62).Theparallelwill returnrepeatedlyinHusserl’swritings,from IdeasI (1913,§10)to FormalandTranscendental Logic (1929,§54)to ExperienceandJudgement (1939,§1).Forageneralanalysis,see Smith (1989); fordiscussion,see Crosson (1962), Scanlon (1975), Poli (1993), Rosiak (1998b),and Smith (2003). 13 Thelistofattemptsinthisdirection,someofwhichquitethorough,islong;see Ginsberg (1929), Sokolowski (1968), Simons (1982a), Null (1983), BlecksmithandNull (1990), Fine (1995), Rosiak (1995, 1996), Casari (2000, 2007), Ridder (2002,§ vi 2),and Correia (2004).

8whatismereology ?

mentainforma,i.e.mathematically.Thuswouldariseacompletelaw-determined surveyofthe apriori possibilitiesofcomplexityintheformofwholesandparts, andanexactknowledgeoftherelationspossibleinthissphere.Thatthisendcan beachieved,hasbeenshownbythesmallbeginningsofpurelyformaltreatment inourpresentchapter.(Husserl, 1900–1901,p. 484)

Asweshallsee,muchcurrentworkinmereologyhasbeeninfluenced bythiswayofthinking.Thelastclaimisespeciallyimportantifwewant tounderstandthephilosophicalmotivationbehindsomeofthemostrecenttechnicaldevelopments.ForclearlyHusserl’sprojectraisesadifficult challenge—thechallengeofdeterminingwhich,amongthemanythings onecansayaboutparthood,shouldbetakenasformallawsintherelevant sense.Afterall,noteverygeneralthesisconcerningidentityqualifiesasformal,either;theprincipleofIdentityofIndiscernibles,forinstance,isasubstantivethesisthatcanhardlybeclaimedtohold apriori,ifatall.Likewise forparthood.Thevexedquestionofwhethertherearemereological atoms, orwhethereverythingisultimately composedof atoms,isobviouslyasubstantivequestionabouttheactualmake-upoftheworld;anyanswerwould amounttoasubstantivemetaphysical(orphysical)thesisthatgoesbeyond a‘puretheoryofobjectsassuch’.Thesamecouldbesaidofothermereologicalthesesthatcometomind,suchasLeibniz’spostulatetotheeffect thatanypluralityofthingswhatsoevercanbeaddedtogethertocomposea furtherthing.Where,then,shouldthelinebedrawn?Whatelseshouldbe includedinthe‘puretheory’ofparthoodbesidestransitivity?Indeedistransitivityagoodcandidatetobeginwith,giventhepuzzlesmentionedearlier inconnectionwithAristotleandBoethius?14 Thesequestionsadmitofno simpleanswer.Butpreciselyforthisreason,thechallengestheyraisemay besaidtohavesettheagendaforthedevelopmentofformalmereological theorieswellbeyondthenarrowscopeofHusserlianscholarship.

1 2 2 MereologyasanAlternativetoSetTheory

Le´sniewski’smotivationsforthedevelopmentofmereologywere,aswe said,significantlydifferent,originatingentirelywithinthephilosophyof mathematics.Heretheincentivewasthenominalisticpersuasionthatset 14 Asamatteroffact,transitivityhassometimesbeenquestionedalsointhecaseofidentity, beginningwithCarneades.AsGalenwrites:

Hedidnotevenbelievethisprinciple,whichisthemostevidentofall:thatquantitieswhich areequaltothesamequantityarealsoequaltooneanother.(Deoptimadoctrina,§2; Galen, 1821,p. 45)

Forcontemporaryexamples,see Prior (1966), Garrett (1985),and Priest (2003).Thesameis trueofthetransitivityoflogicalentailment,atleastsince Geach (1958).Forlogicsinwhich transitivityfails,seee.g. Zardini (2008), Ripley (2012), Cobreros etal. (2012),and Weir (2015).

1 2contemporaryperspectives9

theoryhadbeenconceivedinsin—thesinoffoundingallofmathematics onsuch abstracta asCantoriansets—andthatatheoryofthepart-whole relationcouldprovideamoresolidfoundation.InLe´sniewski’sownwords:

Scentinginthe‘classes’ofWhiteheadandRussellandinthe‘extensionsofconcepts’ofFregethearomaofmythicalspecimenfromarichgalleryof‘invented’ objects,Iamunabletoridmyselfofaninclinationtosympathize‘oncredit’with theauthors’doubtsastowhethersuch‘classes’doexistintheworld.(Le´sniewski, 1927–1931,p. 224)

Le´sniewskiproducedseveralversionsofhistheory.Thefirstversionappearedinanessayentitled Foundationsofthegeneraltheoryofsets (1916);15 theothersarepresentedinaseriesofarticlescalled‘Onthefoundationsof mathematics’(1927–1931),wherethetheorywasofficiallynamed‘Mereology’.Thevariousversionsdifferintheirchoiceofprimitives,resultingin differentsetsofaxiomsanddefinitions:inthefirstversion,thebasicnotion is properpart,whichLe´sniewskitakestoapplytothosepartsofanobject thatarenotidenticalwiththeobjectitself;laterversionsuseasprimitive thenotionof part initsbroader,properorimpropersense,orothernotions suchas disjoint (lackingacommonpart).16 Sincethesenotionsareallinterdefinable,however,suchdifferencesprovetobeimmaterialandwecan speakofLe´sniewski’sMereologyasasingletheory.Andinthiscase,unlike Husserl’s,itisatheorythatwasmeanttobecomplete.Hereareitsaxioms statedintermsofparthood(adaptedfrom Le´sniewski, 1927–1931,pt. vii):17

(a)If x ispartof y and y ispartof x,then x is y

(b)If x ispartof y and y ispartof z,then x ispartof z

(c)Ifevery ϕ ispartofboth x and y,andifevery z thatispartofeither x or y hassomepartthatispartofsome ϕ,then x is y. (d)Ifsomethingis ϕ,thenthereissome x suchthatevery ϕ ispartof x andeverypartof x hassomepartthatispartofsome ϕ. Whetherthistheorycouldinfactserveasanadequatefoundationfor mathematicsisaquestionthatgoesbeyondourpresentconcerns.18 Le´sniew-

15 PublishedasPart i;thecontinuationneverappearedinprint(cf. Le´sniewski, 1927–1931,p. 227).

16 Thisisourterminology,followingcurrentusage.Le´sniewskiused‘part’(cz ˛ e´s´ c)forthenotion ofproperpartand‘ingredient’(ingredyens)forthebroadernotion.Histermfor‘disjoint’was ‘exterior’(zewn ˛ etrzny).Laterdevelopmentsby Soboci´nski (1954), Lejewski (1954a),and Clay (1961)displayanevenwiderrangeofpossibleprimitives;forafullpicture,see Welsh (1978).

17 Strictlyspeaking,theseaxiomsshouldbereadagainstthebackgroundofLe´sniewski’speculiar understandingofthemeaningandlogicofthecopula‘is’andofthequantifiers‘every’and ‘some’.Thisiswheretheothercomponentsofhisoverallsystem,especiallyOntology,become relevant.Forourpurposeswemayignoresuchaspects,butseenote 2 aboveforsomeliterature and Simons (1982c)forhelpfulguidance.Forcompactexpositions,seealso Simons (1987,§2 6; 2018), Ridder (2002,§i 1 2),and Urbaniak (2014a,ch. 5);foranextensivestudy, Gessler (2005). 18 Forafirstassessment,see Simons (1993)and Urbaniak (2014a,§5 3,and 2015).