Mendeleev to Oganesson

A Multidisciplinary Perspective on the Periodic Table

Edited by eric scerri and guillermo restrepo

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

© Eric Scerri and Guillermo Restrepo 2018

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Title: Mendeleev to Oganesson : a multidisciplinary perspective on the periodic table.

Description: New York, NY : Oxford University Press, [2018] | Includes index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017034854 | ISBN 9780190668532

Subjects: LCSH: Periodic table of the elements. | Periodic law. | Chemistry—History—19th century. | Chemical elements.

Classification: LCC QD467 .M4294 2018 | DDC 546/.8—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017034854

Foreword by Roald Hoffmann vii

Introduction 3

CHAPTER 1 Heavy, Superheavy . . . Quo Vadis? 8

Paul J. Karol

CHAPTER 2 Nuclear Lattice Model and the Electronic Configuration of the Chemical Elements 43

Jozsef Garai

CHAPTER 3 Amateurs and Professionals in Chemistry: The Case of the Periodic System 66

Philip J. Stewart

CHAPTER 4 The Periodic System: A Mathematical Approach 80

Guillermo Restrepo

CHAPTER 5 The “Chemical Mechanics” of the Periodic Table 104

Arnout Ceulemans and Pieter Thyssen

CHAPTER 6 The Grand Periodic Function 122

Jan C. A. Boeyens

CHAPTER 7 What Elements Belong in Group 3 of the Periodic Table? 140

Eric R. Scerri and William Parsons

CHAPTER 8 The Periodic Table Retrieved from Density Functional Theory Based Concepts: The Electron Density, the Shape Function and the Linear Response Function 152

Paul Geerlings

CHAPTER 9 Resemioticization of Periodicity: A Social Semiotic Perspective 177

Yu Liu

CHAPTER 10 Organizing the Transition Metals 195

Geoff Rayner-Canham

CHAPTER 11 The Earth Scientist’s Periodic Table of the Elements and Their Ions: A New Periodic Table Founded on Non-Traditional Concepts 206

L. Bruce Railsback

CHAPTER 12 The Origin of Mendeleev’s Discovery of the Periodic System 219

Masanori Kaji

CHAPTER 13 Richard Abegg and the Periodic Table 245

William B. Jensen

CHAPTER 14 The Chemist as Philosopher: D. I. Mendeleev’s “The Unit” and “Worldview” 266

Michael D. Gordin

CHAPTER 15 The Philosophical Importance of the Periodic Table 279

Mark Weinstein Index 305

t he icon of our profession has remained strong and deeply useful because of its nonreducible chemical nature, because of its flexibility in both definition and utilization. And it remains alive not only because of its essence, the way it organizes our elements, but also because of the natural challenges it provokes. Let me explain.

The periodic table has evolved as chemistry has evolved; its meanings are now multiple. That is its strength, not a putative weakness. Useful chemical concepts evolve by appropriation. So the line of Kekulé’s time, a symbol for a then-unknown persistent connection between atoms, in time was assigned the meaning of a shared Lewis pair. This was further coopted by Pauling to stand for a covalent wavefunction. In a similar way, the periodic table of Mendeleev, which began as a summary of valence regularities of the elements in combination, was reinterpreted in the new atomic theory of Bohr (and by the quantum chemistry that followed) as the outcome of a sequential, quantum-mechanically determined filling of atomic orbitals. The table is alive because it can accommodate alternative interpretations that are of chemical utility, that suggest similarities and fruitful substitutions—in chemical reactions to be tried, in physical properties to be desired.

And what do I mean by the challenges it engenders? There were the initial ones, of atomic weights to be believed or not. Quandaries to be added on to, by asking why a table of chemical proclivities in compounds should have anything to do with filling the orbitals of isolated atoms. Should we, for instance, worry or not about the fact that the electronic configurations of the ground states of isolated Ni, Pd, Pt atoms are all different? No, for there is no ambiguity in the configuration taken on by the most common valence state, II, of those atoms in their compounds. And yes, we should think (if not worry) about what that ambiguity in Ni, Pd, Pt ground state atomic configurations tells us of how close the nd, (n-1)s levels are in the three transition series,

I was asked once by Chemical & Engineering News to pick an element to write about. I picked silicon. Not because I had done many calculations on silicon-

containing compounds, but because . . . it was to me the most obvious example of that essential tension of identity, of similarity and difference, of being the same and not the same. Of course, just as the periodic table implies, silicon forms analogues of methane, ethane, and ethylene. And the Si-Si bond length in H 2 Si=SiH 2 is shorter than in H 3 Si-SiH3, just as in the carbon analogues. But . . . there are no bottles of Si 2 H4; it’s a fleeting molecule seen only in a matrix of solid Ne. And—hold on to your pants—quite unlike the carbon case, the enthalpy of the bond-breaking reaction of H2Si=SiH2 to two SiH 2 is actually less than that to H 3 Si-SiH 3 to two SiH3. And in a wide group of compounds, silicon goes five- and six-coordinate, whereas carbon resists that, with a vengeance.

Should we abandon the periodic table, look for a resemblance between C and Al or P? Nonsense. The periodic table gains in interest because (a) we see its limitations, and (b) we try to understand them. Not to substitute another numerology for that the table represents, but to reason out the “why?” that makes compounds of Si different from those of C.

We now have prime evidence for a multitude of exoplanets with conditions approaching those of Earth. Many low-probability accidents of evolution must intervene before conscious, intelligent life develops on these. But the chances of that happening have been much increased by our discovery of the exoplanets. A survivor and an optimist, I have no special desire to see the future; we will find a way, despite what we have done to the planet. Except for one thing— how I would like to learn, in that encounter with extraterrestrial intelligence that must come, how the ETs represent the periodic table! The regularities of atoms, ions, and molecules will be there in their world; but given the vagaries of evolution, the diverse ways we see things worked out in our world, our ET friends will not look the way we do. And the accidents of that piece of cultural evolution we call chemistry (that I am certain will transpire on their world) will have been constructed by them with a different mindset, with different symbols. I just long to see their “table.”

Roald Hoffmann

Mendeleev to Oganesson

Introduction

The periodic Table is ubiquitous in chemistry—as it is in science and in the popular imagination. These days “nerdism” has become a respectable way of being. While science may continue to get bad press, having an expertise in technical matters appears to be increasingly respected. We should all be grateful for the latter if not the former..

The periodic table is one of the areas in science that seems to come under the scrutiny of highly gifted children. Through the YouTube, and the Internet in general, we encounter younger and younger children who are drawn to learning the names of the elements in their correct atomic number sequence.1 What is this scientific and cultural icon that seems to evoke such strong passions even at such early ages?

Much has been written on the periodic table in recent years, including technical articles and books as well as popular expositions aimed at a variety of audiences.2 Why do we need another book on the subject? The answer is that as popular interest in the subject grows it becomes even more important for experts in different fields to provide an ever-deeper analysis of what it is we are all talking about.

This project began some years ago following a conference on the periodic table that was held in the idyllic Peruvian city of Cuzco.3 The organizer, Julio Gutierrez Samanez, has had a lifelong interest in the periodic table, especially its mathematical aspects. It was at this meeting (which included the inevitable excursion to the nearby Inca temple at Machu Picchu) that Scerri and Restrepo conceived of the idea of a book of essays aimed at furthering the foundations of all aspects of the periodic table. We quickly decided that we should also invite authors who might not have attended the meeting. These included mathematicians, physicists, geologists, historians, chemists, semioticians, and philosophers from many different countries and with a variety of interests.

1 Some examples are available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nM52VBSb9vk

2 A full list of all books published on the elements and the periodic table (and in several languages) can be found at www.ericscerri.com.

3 http://www.chemistryviews.org/details/event/2459831/Third_International_Conference_on_the_ Periodic_Table.html. Also see the announcement in Foundations of Chemistry (2012) 14:105–106.

We naturally turned to Oxford University Press as a possible publisher given their recent record in, not to say virtual domination of, the field of books on the periodic table.4 After the usual proposals and discussions the press accepted our project and we began to gather the essays you find collected here.

The 15 chapters of this book show aspects of the periodic system from different perspectives and disciplines, and include new translations of some documents by Mendeleev.

Paul J. Karol, a nuclear chemist, ponders the limits of the periodic table, and the stability of the heaviest elements, and provides a review of the subject in his chapter. Among other things, Karol discusses the nuclear liquid drop model and its different refinements, which he later combines with several electronic approaches. He also claims that nuclei with up to 172 protons are stable.

“Nuclear Lattice Model and the Electronic Configuration of the Chemical Elements” is by Jozsef Garai, a mechanical engineer by profession. The author argues that the periods of the periodic system are related to a lattice nuclear model in which protons and neutrons are regarded as spheres that adopt packing patterns of tetrahedra made of layers of nucleons. Garai argues that the number of protons in those layers is related to the periodicity patterns found in electronic configurations.

Philip J. Stewart, an ecologist by profession, reviews some graphical representations of the periodic system, including the short, medium-long, spiral, and left-step forms of the periodic table. He criticizes the reluctance of chemists to accept other non–medium-long periodic tables. He also points to what he regards as contradiction in regarding hydrogen, a non-metal, as being the head of the alkali metals while rejecting that helium, which is also a non-metal, should be at the head of alkaline-earth metals. Stewart stresses the role of amateurs in devising periodic tables and finally makes a plea for his own favorite spiral representation.

In “Similarity Structure of the Periodic System,” Guillermo Restrepo discusses the differences between the concepts of periodic system, periodic law, and periodic table. The chapter is motivated by Mendeleev’s distinction between basic and simple substance as well as Mendeleev’s insistence on considering the properties of the compounds in the classification of elements. A total of seven similarity studies of the chemical elements based on experimental information are then reviewed, in an attempt to clarify the minimum number of properties needed to characterize chemical elements.

Ceulemans and Thyssen provide a discussion of the foundations of Madelung’s rule and of its interpretations by exploring different approaches from

4 J. Emsley, Nature’s Building Blocks: An A-Z Guide to the Elements; E. Scerri, The Periodic Table, Its Story and Its Significance, OUP, 2007; A Very Short Introduction to the Periodic Table, OUP, 2011; A Tale of Seven Elements, 2013; M. Kaji, H. Kragh, G. Pallo, The Early Reception of the Periodic Table, OUP, 2015. M.V. Orna, M. Fontani, G. Fontani, The Lost Elements, The Periodic Table’s Shadow Side, OUP, 2014.

mathematical physics. This is a topic that is of some importance to chemical education, which habitually attempts to indoctrinate students into being able to write the correct electronic configuration for any particular atom.

Jan C. A. Boeyens, a mathematical chemist, combines information on nucleons with number theory to devise sequences that are related to the periodic system. The author claims that all chemical phenomena displaying periodic trends should be amenable to mathematical analysis. Boeyens also concludes that the results of number theory are completely general and applicable to disciplines other than chemistry.

Eric Scerri and William Parsons are the authors of “What Elements Belong in Group 3 of the Periodic Table?” They claim that group 3 of the periodic table should include lutetium and lawrencium as opposed to lanthanum and actinium. The authors review the many arguments that have been proposed on both sides of the debate and conclude that although the evidence in favor of the proposed change is quite impressive there has yet to be a conclusive argument to satisfy all parties. They proceed to then provide what they consider such a conclusive argument by turning to a long-form presentation of the periodic table and the demand that the elements be strictly ordered according to increasing atomic number.

Paul Geerlings, a theoretical chemist, considers the relationship between density functional theory and chemical periodicity. Geerlings criticizes the quantum chemical approach to the periodic system based on isolated atoms and orbitals. Instead he presents an alternative approach based on electron density and on the amount of information among atoms. He adopts what may be termed a more “realistic” approach to the chemical elements by considering perturbed atoms rather than those in isolation.

Yu Liu, a semiotician, makes a semantic argument for having several periodic tables. With reference to two particular periodic tables published by John Newlands, the author examines the shifts of interests and meanings that Newlands wanted to address. Liu claims that different kinds of relations were depicted by Newlands including that of mereology, which in turn was related to the concept of a chemical period. Liu concludes that chemical periodicity is far from having a resolved meaning; rather, its meaning is constantly being negotiated.

Inorganic chemist and chemical educator Geoff Rayner-Canham discusses several classifications of transition metals and one that includes groups 4 to 11 of the periodic table. The author suggests a novel classification based on the aqueous chemistry of the compounds of elements. Rayner-Canham claims that the traditional approach through groups and periods is not appropriate to the similarities among transition elements. The author suggests a mixture of vertical and horizontal similarities and that one element may take part in more than one similarity class.

Bruce Railsback is the author of “The Earth Scientist’s Periodic Table of the Elements and Their Ions: A New Periodic Table Founded on Non-Traditional Concepts,” where chemical elements do not occupy a single position but rather several of them, depending on their oxidation states. The table especially

includes information on chemical elements present in materials of geochemical interest. Railsback’s table is divided into four blocks or neighborhoods according to the oxidized forms of the elements: hard, intermediate to soft cations, anions, and noble gases, which in turn are further divided into finer neighborhoods. Railsback suggests that the table can be used to highlight interactions between chemistry and various other disciplines.

The chemical historian Masanori Kaji analyzes the scientific and social conditions which gave rise to Mendeleev’s system. He examines how Mendeleev’s interests in analytical chemistry, isomorphism, specific volumes, indefinite compounds, and the classification of organic substances led him to develop his ideas of chemical element and to devise his periodic system. Kaji also shows how the creation of the Russian Chemical Society motivated Mendeleev to write his famous chemistry textbook, which in turn led him to discover the periodic system. This chapter also includes a complete English translation of Mendeleev’s letter replying to accusations that he was not doing “real work.”

The chemical historian and educator William B. Jensen discusses Abegg’s rule of eight, which represented the first attempt to interpret the periodic system in electronic terms. Jensen reformulates and extends the rule to the concept of a valence manifold by using valence electrons and vacancies. Several controversial questions regarding the placement of elements in the periodic table are addressed. Jensen concludes hydrogen and helium should be separated from each other, that lanthanum and actinium should be grouped with the innertransition, and that the zinc group elements are main-block elements.

The studies of the philosophical views of Mendeleev have been mainly based on translations of his scientific publications. However, as Michael Gordin states in his chapter, Mendeleev wrote two explicitly philosophical documents that Gordin translates for the first time into English. These documents are thoughts that Mendeleev appears to have hesitated from sharing openly. “The Unit,” written under a pseudonym, reveals Mendeleev’s views on spiritualism while “Worldview,” a posthumously published document, contains his political and economic views in the midst of the first Russian revolution.

The final contribution in this multidisciplinary compilation is perhaps the most philosophical of all the studies presented. In it Mark Weinstein considers the methodology, and in particular the role of counter-evidence, in evaluating generalizations. He then examines how the table permits a reinterpretation of foundational epistemological notions of truth, and finally asks how the periodic table supports our commitment to the fundamental nature of reality.

We hope that these essays will further stimulate interdisciplinary as well as multidisciplinary studies on the central icon of chemistry—whose status is still widely debated. There is still widespread disagreement as to whether it should be regarded as a representation, a model, a law, and so on. Perhaps one should avoid even trying to categorize it according to the usual criteria that are imposed by philosophers of science; perhaps one should embrace the uniqueness of the periodic system or simply regard it as the paradigm or framework of modern chemistry.

We end on a sad note in reporting that while this book was in press two of the authors, Masanori Kaji and Jan Boeyens passed away. They will be deeply missed by their families, friends and colleagues, including the editors and other authors represented in this volume. We also acknowledge the passing of Ray Hefferlin who spoke at the Cuzco meeting on the periodic table and who appears in the group photograph above.

Figure 0.1 Left to right: Rolando Alfaro, Elisa Seidner-Scerri, Eric Scerri, Alberto Vela, Pieter Thyssen, Alfio Zambon, Inelda Hefferlin, Ray Hefferlin, Ana María Gutierrez, Guillermo Restrepo, Margarita Viniegra, Heidi Rubio, Adolfo Gutierrez, Julio Gutierrez.

CHAPTER 1

Heavy, Superheavy . . . Quo Vadis?

Paul J. Karol Department of Chemistry, Carnegie Mellon University, USA

uranium was discovered in 1789 by the German chemist Martin Heinrich Klaproth in pitchblende ore from Joachimsthal, a town now in the Czech Republic. Nearly a century later, the Russian chemist Dmitri Mendeleev placed uranium at the end of his periodic table of the chemical elements. A century ago, Moseley used x-ray spectroscopy to set the atomic number of uranium at 92, making it the heaviest element known at the time. This chapter will deal with the quest to explore that limit and heavy and superheavy elements, and provide an update on where continuation of the periodic table is headed and some of the significant changes in its appearance and interpretation that may be necessary. Our use of the term “heavy elements” differs from that of astrophysicists who refer to elements above helium as heavy elements. The meaning of the term “superheavy” element is still not exactly agreed upon and has changed over the past several decades. “Ultraheavy” is occasionally used. Interestingly, there is no formal definition of “periodic table” by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) in their glossary of definitions: the “Gold Book.” But there are plenty of definitions in the general literature—including Wikipedia, the collaborative, free, internet encyclopedia which calls the “periodic table” a “tabular arrangement of the chemical elements, organized on the basis of their atomic numbers, electron configurations (electron shell model), and recurring chemical properties. Elements are presented in order of increasing atomic number (the number of protons in the nucleus).”

IUPAC’s first definition of a “chemical element” is: “A species of atoms; all atoms with the same number of protons in the atomic nucleus.” Their definition of atom: “the smallest particle still characterizing a chemical element. It consists of a nucleus of positive charge (Z is the proton number and e the elementary charge) carrying almost all its mass (more than 99.9%) and Z electrons determining its size.” Our approach here will be to start with some necessary historical context, followed by a look at the nucleus, without which there would be no atom, and then an examination of the electrons, without which there would be no atom.

Early thoughts on heavy elements trace back at least to John Newlands, an English analytical chemist and one of the earliest contributors in developing a periodic table. Following Mendeleev’s proposal, Newlands noted that “All our views on the subject of the ordinal numbers to be attached to various elements are liable to be corrected by the light of future experience. There may be elements having atomic weights as much above uranium as uranium is above hydrogen” (Newlands 1878). Since neither electronic structure of atoms nor nuclear theory had been launched yet, speculations on new elements could proceed without restraint. And did.

In the nearly one-and-a-half centuries since Mendeleev, conjecture about the number of possible elements has been erratic, as illustrated in the historical summary in Table 1.1, which is based partially on the work of Kragh and Carazza (1994) and Kragh (2013 q.v.). Obviously, very early speculations about heavy elements are beyond incorrect physics, they were wild guesses. Neither atomic nor nuclear structure was launched. As to more recent speculations, all the proposed physics may be amiss since the leaping extrapolation from Z = 118 to Z ~ 175 involves enormous relativistic effects that are of unknown/unproven applicability. To this day, relativity and quantum mechanics are not unified. Calculations depend on approximations which are likely unjustifiable as Z increases since the corrections depend very strongly on increasing Z to a power argued to be at least the square, if not the fourth power.

To an extent, much of the speculation was fueled by the discovery of radioactivity revealing the phenomena of transformations and isotopy. Ernest Rutherford and Marie Curie helped clarify the process of radioactive decay, although the physics behind the phenomenon was still a total mystery. Their efforts eventually revealed the uranium decay series.

The series begins with 238U, shown on the right in Figure 1.1 below and, through a now-known chain of alpha-decays (downward arrows) and betadecays (upward arrows), terminates in stable 206Pb on the left in the figure.

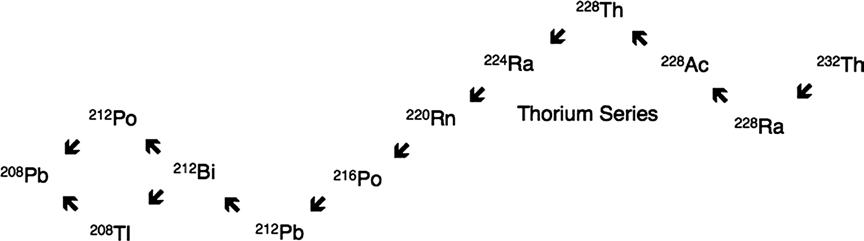

Two other series, the thorium series and the actinium series, were also established. One series began with thorium (Fig. 1.2) and the other (Fig. 1.3) with a lighter isotope of uranium—at the time called “actino-uranium.”

The history of these efforts is well-covered in Marjorie Malley’s “Radioactivity” (2011).

Figure 1.1 Uranium decay series commencing with 238U and terminating at 206Pb. Downward arrows are alpha decays and upward arrows represent beta decays.

table 1.1 History of predictions about the upper limit of the periodic table proposed by year z

J. Newlands 1878 A → 480

E. Mills 1884 92

V. Meyer 1889 100

C. Baskerville 1901 93

S. Losanitsch 1906 >92

W. Tilden 1910 92

N. Bohr 1922 hundreds or thousands

S. Rosseland 1923 92

S. Rosseland and N. Bohr 1923 137

A. Sommerfeld 1924 137

R. Swinne 1926 110

J. Jeans 1926 thousands

M. Snyder 1926

E. Meyer 1927

W. Gordon 1928

W. Nernst 1928 >92

W. Kossel 1928 <137

H. Flint and O. Richardson 1928

W. Glaser and K. Sitte 1928 90.5

J. Jeans 1928 95

S. Stone 1930 A<340

G. Lemaître 1931 millions

A. Eddington 1932

V. Narliker 1932 92

O. Koblic 1934 93

G. Gamow 1942 several times > 92

F. Werner and J. Wheeler 1958 147

B. Fricke and W. Greiner 1971 172

A. Migdal 1974 > (137)3/2 ~ 1600

J. Berger et al. 2001 ≈300

V. Nefedov 2006 164

A. Khazan 2007 155

J. Emsley 2011 128

W. Brodziński and J. Skalski 2013 126

Figure 1.2 Thorium decay series commencing with 232Th and terminating at 208Pb. Downward arrows are alpha decays and upward arrows represent beta decays.

Figure 1.3 Actinium decay series commencing with 235U and terminating at 207Pb. Downward arrows are alpha decays and upward arrows represent beta decays.

James Jeans, a British physicist and astronomer, contributor to the field of modern cosmology, and author of “The Kinetic Molecular Theory of Gases,” hypothesized that elements with atomic numbers even a thousand times greater than that of uranium exist in stars (1928). The need for such superheavy elements was, at the time, a missing ingredient to explain the huge energy production exhibited by the sun.

First, the Atomic Nucleus

In 1929, a bit before the discovery of the neutron, the Russian physicist George Gamow, working in Niels Bohr’s institute, published the first theory of nuclear structure (1930). In it he referred to a liquid drop model based on the theory of capillarity. The drop model plays an essential role in discussing the behavior, observed and predicted, for heavy nuclei. Gamow developed an expression for the energy of such a drop, consisting (for simplicity) of alpha particles in which the necessary attractive forces were short-ranged (as with capillary action in a macroscopic liquid) but of unknown strength. By matching predictions of the nuclear drop model energies with Aston’s 1927 published mass measurements, Gamow was able to demonstrate a primitive agreement. There was a major problem with the prediction though: At nuclear masses of 120 or higher, instability toward radioactive decay was predicted despite the perceived absence of instability through masses of about twice that value. The fact that nuclear masses were approximately twice the atomic numbers was accommodated, as usual for these times, by assuming that many more protons and alpha particles in the nucleus were accompanied by a sufficient number of electrons within the nucleus itself to account for the eventual balance and mass number, A (equaling N + Z, number of neutrons plus number of protons).

Only a few years after the discovery of the neutron by British physicist James Chadwick in 1932, Gamow’s nuclear drop model was adapted by German theoretician Carl von Weizsäcker into an extended form of the liquid drop model leading to the semi-empirical mass formula (1935), a very successful stratagem for understanding major bulk characteristics of atomic nuclei.

On July 5, 1934, Czechoslovak newspapers reported that an element with atomic number 93 and atomic weight 240 had been discovered in Joachimsthal pitchblende by Odelon Koblic, Director of the National Uranium and Radium

Plant in Joachimstal (1934). The logic behind Koblic’s search was very reasonable. An element heavier than uranium had to exist in order to explain the chain of radioactivities that included actinium (10-day 225Ac) in a fashion identical to the three uranium series already quite well-characterized. But within the year, a retraction of the evidence was published as no characteristic x-radiation could be found to confirm the new substance. Neptunium was discovered in 1940 and the now-known series appears below in Figure 1.4. Its parent isotope (half-life of 2.1 million years) is too short-lived to be naturally occurring: any original neptunium is extinct.

As we begin to consider understanding the extension of the periodic table beyond uranium, we must deal with the stability of the nucleus itself without which, of course, there would be no elements. With a stable nucleus, the second consideration is the stability of the electronic structure, a requirement to have atoms and then, ipso facto, an element, according to definition. Beginning just with stability of the nucleus is our chosen approach.

The nuclear liquid drop model is a very simple and effective recipe for many major features of nuclear stability. From early measurements of nuclear size using alpha particle scattering measurements, the nuclear radius, r, was seen to be proportional to the cube root of the mass number, A1/3. From this observation one may infer that the nuclear force between the constituents of the atomic nucleus (initially thought to be only protons and electrons, eventually recognized to be protons and neutrons) had to be short-ranged leading to a saturation effect qualitatively similar to the forces between molecules in ordinary liquid matter. Increasing the numbers of nuclear particles, collectively termed nucleons, would increase the volume of the nucleus, meaning the total number of “bonding” interactions would likewise increase. The total “bonding” energy would then be proportional to the nuclear volume ( π ∝ 3 4 3 rA) and the proportionality coefficient would depend on the strength of the nuclear force, unknown, and therefore just represented as a constant-to-be-determined, avol. Recalling the behavior of ordinary liquids, as long as the volume is small, there is a considerable surface tension owing to the absence of “bonding” external to the surface of the drop. The magnitude of that surface effect reduces the total bonding energy by an amount proportional to the number of (bonding

Figure 1.4 Neptunium decay series commencing with 237Np and terminating at 209Bi. Downward arrows are alpha decays and upward arrows represent beta decays.

unsaturated) particles on the nuclear surface. That, in turn, varies with the surface area. The strongest total bonding will occur when the reduction due to the surface effect is minimal, namely with a spherical shape. The surface area of a sphere ( π 2 4 r ), and therefore the dependence of the surface binding energy reduction, consequently depends on A2/3. To summarize to this point, the total binding energy, EB, of a spherical drop of liquid can be written as

Bvolsurf EaAaA

However, within the nucleus are Z positively charged protons that are mutually repelling each other, reducing the net attractive bonding strength accordingly. Electrostatic (coulomb) repulsion energy among particles is proportional to the product of the charges and inversely proportional to the distance between them. A collection of Z protons is each repelled by the other Z-1 protons and the average distance of separation is proportional to the size of the nucleus, r, which depends on A1/3. Proceeding to the binding energy of a charged liquid drop, we have

In this case, the coefficient acoul is actually known since it incorporates classical electrostatic energy constants.

If we ceased our development of the nuclear liquid drop model at this point, the composition (Z,A) of any nucleus corresponding to the maximum binding energy and therefore the highest stability for that A would be such that Z = 0 or 1. Not very encouraging. But missing from the development at this stage is an important quantum effect. Modern quantum mechanics had already been launched by the time of the nuclear liquid drop model’s construction. The constituents of the atomic nucleus were known to be protons and neutrons, both of which obey the same Pauli Exclusion Principle so essential to the electronic structure of atoms: two protons per quantized energy state and two neutrons per quantized energy state within the nucleus: spin up, spin down. As an example, considering four nucleons; having two protons and two neutrons in the lowest state for each species is one possibility. Having two protons in the lowest state and a third in the next higher state (as required by the Exclusion Principle) with one neutron in the lowest state would be higher in energy than the previous configuration. The mirror image alternative having two neutrons in the lowest state and a third in the next higher state with one proton in the lowest state is accommodated by exactly the same energy increase.

Generalizing this picture, the most favorable configuration, considering just the effect of the Exclusion Principle and quantized levels, is that any departure from a composition that has equal numbers of protons and neutrons is higher in energy than that symmetric composition. A detailed consideration of the quantum effect of symmetric composition of nucleons, two different spin ½ particles, gives us the next term in the total binding energy, a term that reduces the energy for compositions where Z and N are not equal.

The symmetry effect is most important for light nuclei since it is inversely proportional to A. It explains why the most stable light nuclei have N = Z, or at least nearly so. Illustrating this with a few examples we have the most stable nuclei with mass numbers A = 4, 16 and 40 being 4He, 16O, and 40Ca.

Although the details of the nuclear force were unknown, Weizsäcker was able to use measured masses to get values for the four coefficients in the expression for EB. Since the energy equivalent of a mass equals mc2 where c is the speed of light:

MZ,Nc+ E= ZMc+ ZMc

( ) 222 BHn

In this expression M(Z,N) represents the atomic mass of the isotope of element Z with N neutrons and MH represents the atomic mass of hydrogen. Mn is the neutron mass. Atomic masses are used because they are what is determined in mass spectrometer measurements and the number of electrons, equal to Z, is conserved on both sides of the above equation. Consequently, mass measurements allow evaluation of EB for each isotope. Best values for avol, asurf, and a sym can then be extracted from fitting the data.

An additional property that emerges from the nuclear liquid drop model is the ability to get a firm grasp of the energetic considerations of radioactive transformations. For example, the decay of 238U into 234Th plus an alpha particle 4He involves a decay energy expressible as

( ) ( ) ( ) 234 238 MThc+2422 MHec– MUc

Substitution converts this into the decay energy in terms of binding energies:

( ) ( ) ( ) 234 238 4 BBB ETh+EHe–EU

for which either the experimentally determined values can be used or the model predictions from the nuclear liquid drop picture. The model’s predicted value is 4.1 MeV and the experimental value is 4.3 MeV. Interestingly, what emerges is that any element with a mass above about 140 is unstable with respect to alpha decay. Energy available or unavailable (negative values) for alpha decay along the smoothed trend of stable compositions is shown in Figure 1.5.

For lighter systems the negative energies shown below suggest that fusion of an alpha particle with a nucleus is energetically feasible; it is effectively the reverse of emission. Why alpha-decay isn’t prevalent just above its threshold in practice is resolved by the well-known dichotomy in ordinary chemistry: thermodynamic (energetic) considerations versus kinetic (rate) considerations.

As far back as 1911, the strong connection between the energy release in alpha-decay and the rate at which the transformation occurred was recognized. That relationship was first embodied in the Geiger-Nuttall Law which gave the

Energy for alpha decay along line of stability for smooth liquid drop

Figure 1.5 Energy available for alpha decay as a function of nuclide mass number A for the most stable nuclide at that mass number. Negative energies means the decay is thermodynamically forbidden.

variation of the alpha-decay half-life as log t1/2 being proportional to / ZEdecay . Thus a small increase in decay energy could be reflected as a very large increase in the rate of decay and vice versa. In 1928, George Gamow explained the Geiger-Nuttall empirical relationship by devising a theory of alpha-decay involving the quantum mechanical tunneling of the alpha particle through the nuclear electrostatic barrier (Gamow 1928). Following this model, it is easy to understand why alpha-decay around A = 140 with very little energy available for decay would proceed exceptionally slowly, as observed in the rare cases where such nuclear behavior has been measured. (144Nd has an observed halflife of 2.4 quadrillion years.) Alpha-decay is spontaneous above A~140 but not necessarily instantaneous.

The rate of decay plays an essential role in looking at very massive systems but we will postpone consideration of this aspect of nuclear behavior until later.

The liquid drop model can also be employed to recognize that there are limits to how many or how few neutrons a nucleus can tolerate before the binding of an additional neutron or proton goes to zero. Predicted limits on composition result. 400U, for instance, will not persist but will hemorrhage neutrons spontaneously and nearly instantaneously until stability is achieved again at around 300U. (The most massive uranium isotope known is 242U.)

A much more illustrative approach to nuclear stability is to look at the average binding energy per nucleon, EB/A. For a bulk liquid, this average would be constant, independent of the size/volume of the bulk liquid under consideration. But as the volume of the liquid approaches zero (nuclear size), the surface effect becomes important and the average binding energy decreases significantly. That is exactly what is observed. On the other hand, as the volume of our nuclear system increases, as the number of particles increases, the binding energy per particle also begins to drop. This is understandable from

the contribution of the coulomb repulsion effect in which, as we go to higher and higher elements, more and more protons counteract the net effect of the short-ranged attractive nuclear force. Our quest here is to explore what happens as heavier and heavier systems are considered.

Quantitatively, the simplified version of the liquid drop model here when fitted to mass-derived data gives what is frequently called the semi-empirical binding energy formula with units of MeV:

A graph of the average binding energy per particle is displayed quantitatively for the most stable nucleus at each mass number A in Figure 1.6. As implied in the above expression, for fixed A, the maximum binding energy can be found as a function of Z and would correspond to the most stable element, ZA, at that mass number. The approximate expression that emerges is

Although we have omitted several important aspects of nuclear structure from our treatment so far, the above illustration serves to demonstrate some interesting features of the most stable nuclei. There is a peak in stability around A = 60 corresponding to nickel and iron isotopes. As we get to much heavier nuclei, fission into two more tightly bound fragments becomes energetically favorable. Fission was discovered by German nuclear chemists Otto

Figure 1.6 The liquid drop model average binding energy EB per nucleon along the valley of stability as a function of A, the number of nucleons in the nucleus.

Hahn and Fritz Strassmann in 1938. Within the year, Austrian physicists Lise Meitner and (her nephew) Otto Frisch came up with an explanation of fission based on the liquid drop model of the nucleus. If 238U hypothetically splits exactly in half, the product 119Pd’s are not themselves stable and so Figure 1.6 is inaccurate for that nucleus. Our simple formula gives ZA for A = 119 as close to 119Sn, not 119Pd. Nevertheless, the energy released in splitting, calculated from the binding energies, still exceeds 150 MeV. That energy is typical for what is available to fission for heavy nuclei. As with alpha-decay, fission is disfavored by a Coulomb barrier, the energy needed to overcome the electrostatic repulsion associated with the two large ≈ Z/2 fragments. The liquid drop model provides a very straightforward scheme for estimating the composition at which the barrier to fission vanishes implying instantaneous fission, that is, instability.

A nucleus undergoing fission, splitting into two fragments, has to distort its spherical shape—stretching, forming a neck, and breaking in two. The process affects two features of the drop model through the shape change: the surface area will increase (since the single original sphere has the smallest area) and the electrostatic repulsion will decrease (since the average distance of separation between protons will increase). For small distortions from the original spherical shape, the surface energy and the electrostatic coulomb energy will change from their original spherical values, 2/3 0 = surfsurf EaA and ( ) 1/3 0 1 =−coulcoul EaZZA , according to

in which β is a measure of the distortion. Total volume is conserved as is the total contribution of neutron-proton asymmetry energy of the two fragments which maintain the same relative composition as the fissioning parent. Distortion of the spherical shape on the way to fission leads to a total change of energy:

The path to accomplish fission requires no additional energy when ΔEdist = 0 or

which, upon reference to the semi-empirical equation for the liquid drop model becomes