Introduction

I start with what for me is a puzzle. An analytic sentence is a sentence one can see to be true simply by understanding it (and, perhaps, using a little logic). The hoary example is the sentence ‘all bachelors are unmarried’: to understand the sentence one must understand the word ‘bachelor’, knowing that it means unmarried man; so to understand the sentence is not just to know that it says that all bachelors are unmarried but to know that it says something that comes to no more and no less than that all unmarried men are unmarried. But any rational animal who can think the thought that all unmarried men are unmarried knows it.

I accept Quine’s observation in ‘Two Dogmas of Empiricism’ that no sentence, not even ‘all bachelors are unmarried’, is beyond rational revision. I take it to imply that there are not and could not be analytic sentences. But I take seriously the worry Paul Grice and Peter Strawson expressed about Quine’s position. Quine’s view, they pointed out, seems to lead to the conclusion that there is no sense to be made of the idea that expressions can be synonymous, which in turn suggests that talk of meaning is senseless. Thus the puzzle: Can we agree with Quine that there are no analyticities without saying that talk about the meaning of the word ‘bachelor’ is senseless?

Quine’s remarks at the end of ‘Two Dogmas’ suggest a certain picture of our way of being in the linguistic world. At any time, the way we use our words gives them a particular role in inference: for example, our current way of using ‘bachelor’ gives a double thumbs-up to the inference Paul is married; so Paul is not a bachelor. Our linguistic activity also embodies presuppositions about the world and assumptions about how others will use their words when they speak. The inferential role and presuppositions accompanying our words determine how we use our language as a tool for inquiry and communication. But the inferential roles and presuppositions that determine use are fluid and dynamic. How we should proceed in the face of ‘recalcitrant experience’ isn’t determined at the outset, and we can change course—change the presuppositions and inferential role that accompany our words—when it seems apt. So there are no epistemically fixed points in the history of inquiry. Quine’s fundamental worry about analyticity, I think, was that whatever an analytic sentence is supposed to be, it would have to be a fixed point in inquiry.

Now in this picture there is something that plays the role of the meaning of a term—its inferential role and the firmly held presuppositions about use and the world that are associated with it. But this meaning is inherently dynamic. It’s not a fixed Fregean sense or

Platonic universal, but a constantly evolving set of hypotheses, inferential dispositions, and expectations about the world and the speech of others.

There is also something that potentially functions as a criterion of ‘sameness of meaning’. Changes in inferential role or in presuppositions that result in fluid conversation being stymied or in the role of a sentence in inquiry being radically revised can be sensibly called changes in meaning. If, of a sudden, the noun ‘duck’ takes on the role of the noun ‘cookie’—well, that would be a change of meaning. But the statement-sized alterations that Quine had in mind in ‘Two Dogmas’—dropping, say, the belief that ducks are birds while preserving the thought that ducks are fuzzy-feeling aquatic things given to airborne migration—those sorts of changes needn’t upset the apple carts of inquiry and conversation. On this picture, ‘meaning identity’ is not unlike artifact identity. A change in a few of the planks and nails that constitute Theseus’ ship doesn’t make the ship disappear; a sudden, wholesale replacement of the wooden parts with aluminum ones does.

Returning to the puzzle we began with: There are no analyticities because nothing plays the role in inquiry and communication that something would have to play to count as analytic. That doesn’t mean that there isn’t a phenomenon that deserves to be called ‘meaning’. But it’s an inherently dynamic one, and sameness of meaning is a lot like sameness of ship. At the end of the day, many of our ordinary and theoretical judgments of sameness of meaning—both diachronic and synchronic—are judgments of similarity that we frame in the language of identity. Nothing wrong with a little idealization so long as we are aware that we are idealizing.

For the moment, let us not quibble with those who are internalists about language. Let us, that is, allow that languages are (in part, at least) psychological structures which, molded by the idiosyncratic histories of speakers in acquiring their tongues, invariably vary in details of pronunciation, syntax, and meaning; each speaker thus speaks her own language. That granted, when speakers are in actual and potential communication there is typically an enormous amount of similarity in their languages. Communication and language acquisition conspire to insure this: enough evidence that others use a word in ways different than I tends ceteris paribus to reproduce the others’ usage in my idiolect. The linguistic sins of the father tend to be visited on the dialect of the daughter. Speakers in actual and potential communication have similar idiolects; they tend to associate very similar inferential roles and presuppositions with their words. Of course, for all the similarity there is diversity, not only in presuppositions but in phonology, morphology, syntax, and so on. Linguistic individuals interact, and these interactions produce changes in the idiolects of the interactors. These changes are typically ones in which the language of one speaker comes more or less permanently to resemble the language of those with whom he interacts. These changes—that is, the properties acquired because of linguistic interaction—can be and often are transmitted down the road to others. Some such changes spread aggressively across a population whose

members communicate with one another; others fizzle or even disappear; yet others (think of slang) persist in a minority equilibrium. Over time enough changes in the linguistic behavior of a linguistic lineage may lead to linguistic behavior that is radically different than the behavior from which it descended.

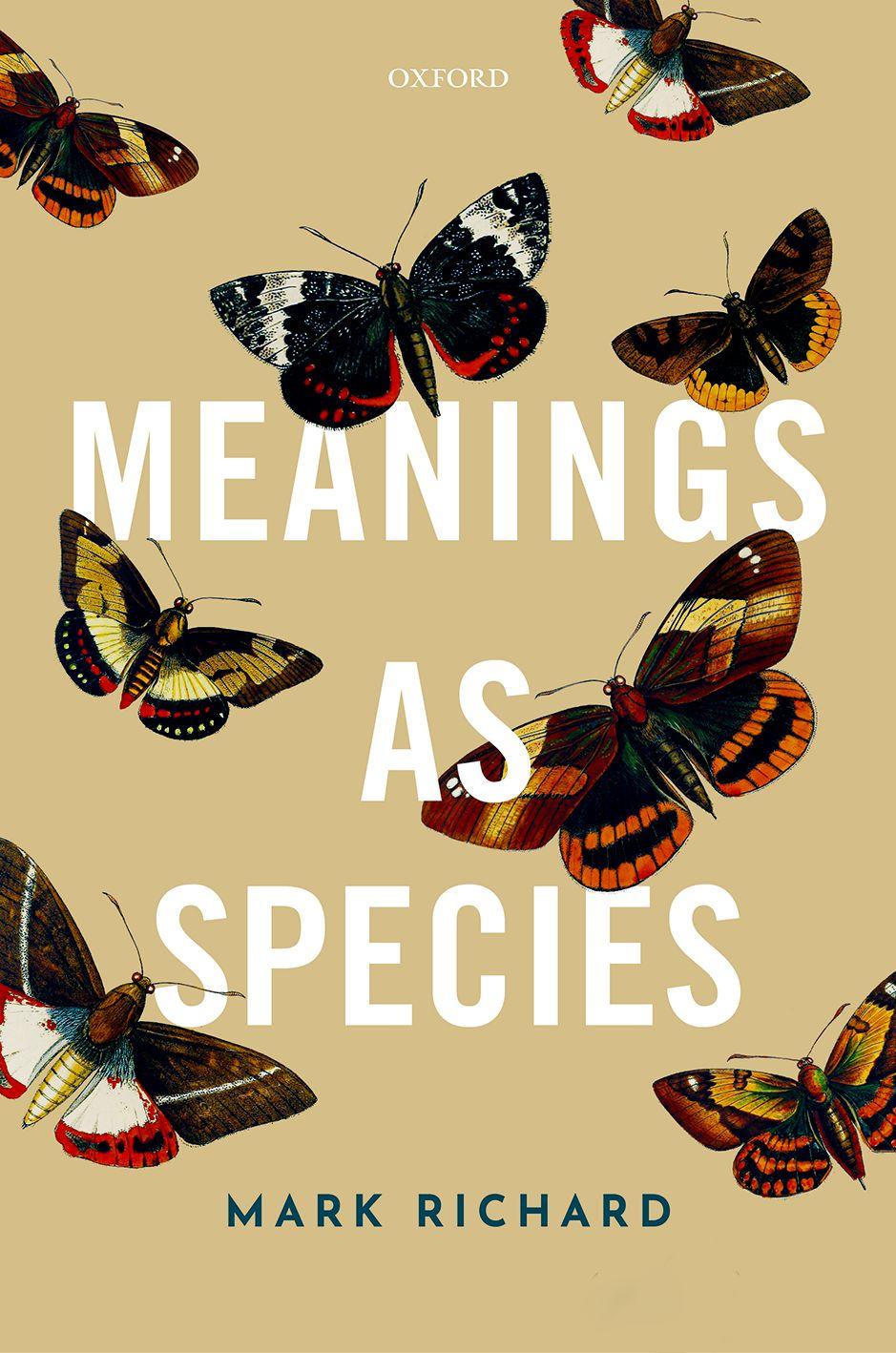

To me—and, I hasten to say, to many linguists, as my analogy is hardly novel—it is striking how much this resembles the biological world. There we find populations of individuals who are very similar—they have similar genomes. The members of a population interact with another—I believe ‘hook up’ is the biological term—with the interactions resulting in individuals who tend to resemble the interactors. Over time, individuals who make up a population lineage may, as changes in transmitted properties become fixed in the population, become so different from their ancestors that we say they are of a different species.

What follows investigates whether linguistic entities—in particular, word meanings— are well understood when we think of them as being like those segments of population lineages that we label species. I think we gain a certain amount of illumination if we combine the idea that meanings are species-like with the picture of meaning that a little while back I ascribed to Quine. *

If meanings are species-like, what exactly are they? What, for example, is the meaning of ‘cousin’?

When a speaker speaks, she makes presuppositions that she expects her audience will recognize as made, ones she expects the audience will have ready for use in making sense of what she says. Some such presuppositions are tied to particular words and accompany their use. When we speak of cousins using ‘cousin’, we expect to be recognized as talking about parents’ siblings’ progeny; we expect the audience can access the idea, that this is what cousins are, in interpretation. For some such presuppositions, it will be common ground in a linguistic community that speakers make them and expect that to be recognized by their audience. I call these sorts of presuppositions interpretive common ground—ICG for short. It is, for example, ICG among English speakers that ‘cousin’ is a term for cousins, and cousins are parents’ siblings’ progeny; speakers presuppose this and expect the presupposition to be recognized and used in interpretation; everybody is cognizant of this. I say the meaning of lexical items is, to a first approximation, ICG in the sense just sketched.

You should say: What do you mean by ‘meaning’? I could mean something like the determinant of reference and truth conditions, something like what David Kaplan calls character. Or I could mean something that can be asserted, believed, and so on, something associated with a sentence’s use by convention and context, or more idiosyncratically by a speaker. Or I could mean meaning in the sense of that with which one must be in cognitive contact in order to qualify as a competent speaker in a population.

I mean the last. ICG is relevant to reference and truth, but reference and truth can’t be read off it, if only because what’s common ground is often erroneous. There is, I think, a

sense of ‘what is said’ in which what is said by a sentence is determined by the ICG of its phrases and their referential semantic values; there are other senses of ‘what is said’ in which ICG (and reference) does not determine what is said. ICG is meaning as the anchor of linguistic competence; it is what knits us together as beings who share a language and thus can communicate.

ICG is pretty clearly a species-like phenomenon. Pick a herd of individuals in actual and potential communication with each other, a herd whose communication is intuitively a matter of their sharing a common tongue. Pick a word—that is, a particular morphology and phonology married to a syntactic role—that is part of the common tongue. Let’s say we picked the English speakers of Newton Highlands MA in 1962 and the word ‘marry’. Members of the herd assume that everyone knows that when people use ‘marry’, they make certain presuppositions which they expect their audience to recognize as being made and to invoke if necessary in interpretation. Members of the herd, for example, assume it’s commonly known that when a speaker uses ‘marry’ she assumes that the word picks out a relation that can only hold between a man and a woman; the herd knows that (all know that) speakers expect the audience to recognize this. Each member of the herd has a ‘lexical entry’ for ‘marry’ that is in part constituted by those presuppositions she takes to be commonly made by users of the word. There will be a good deal of similarity from one entry to another, as speakers tend to cotton on pretty quickly to what all assume all assume. But just as there is variation among the genomes of individual speakers, so will there be variation across the flock about what is commonly presupposed by users of ‘marry’: Just as some of us have green eyes and others blue, some of us think that people think marriage between second cousins is forbidden, while others think this is not what people think. Just as genomes in a population lineage display allelic variation, so do lexical entries. And over time the contours of such variation may shift as a result of speakers’ interactions with one another and with the social environment, as the usefulness of an assumption about a word for understanding its use shifts. The presupposition that people think that (people think that) same-gendered marriage is impossible, for example, has gone by the wayside.

The task of the first three chapters of this book is to set out in some detail the two ideas I’ve been pointing at. Those chapters argue that we should honor Quine’s insights about analyticity and synonymy, not by abandoning the notion of meaning, but by seeing meaning as a dynamic, population-level phenomenon. And they set out the idea that what I’ve called interpretive common ground is an important kind of meaning: it has some call to be said what we are trying to articulate when we engage in philosophical analysis; it is meaning in the sense of what anchors linguistic competence. To be a competent speaker of a group’s language, I argue, is in part to ‘have the right relation’ to the ICG of the words the group shares.

Chapter 1 shows how Quine’s remarks about meaning and analyticity strongly suggest a picture of meaning on which the biological analogy is apt. There has been and

continues to be pertinacious resistance among philosophers to Quine’s conclusions in ‘Two Dogmas’, and Chapter 2 discusses some notable responses to Quine—for example, the complaint that Quine couldn’t be right because, well, obviously we could simply stipulate that a novel expression is to mean what an existent phrase does, as well as the idea that broadly Bayesian accounts of rational credence supply all we need to define what it is for a speaker’s uses of an expression to mean the same thing from one time to another. Chapter 3 begins with a discussion of the idea that much of what’s called philosophical analysis is a sort of conceptual (or meaning) analysis. Developing this idea quickly leads to a picture of (one kind of) linguistic meaning as ICG. It takes a fair amount of work—all of it great fun, I assure you—to develop this picture; if you are skeptical of the theoretical utility of the idea of meaning-cum-ICG on the basis of the five paragraphs devoted to it above, I pray you hold your skepticism in abeyance until you’ve finished Chapter 3.

Species can and usually do evolve without ceasing to be. But evolution can and does lead to the existence of new species, the death of old. It is a nice question as to what the conditions, interestingly necessary or sufficient, are for a species to come or cease to be. If meanings are species-like, there is a question aussi belle as to when linguistic evolution leads to a linguistic form’s having a new meaning. Chapter 4 takes up, but doesn’t pretend to solve, this question. It makes a proposal about the sorts of synchronic relations speakers need to stand in order for it to be apt to say that they share a language, and thus for their words to share a meaning. But answering the question, What makes my contemporaries speakers of my tongue?, isn’t answering the question, What makes future speakers who use the sentences of my tongue mean what I mean with those sentences?

One approach to this question asks under what conditions it is apt to say that in five (or ten or ten to ten to the ten) minutes, a use of a sentence will say the same as its current use. The not unreasonable thought behind this approach is that since a sentence’s meaning is an important determinant of what it can be used to say, switches in saying power tend to indicate mutation of meaning. Since it’s natural to think that what an utterance says is in part determined by the reference of its parts and the truth conditions of the whole, this thought leads to the thought that preservation of reference is necessary for sameness of meaning. Chapter 4’s midsection is devoted to developing the beginnings of an account of the conditions under which one can reasonably ascribe same saying across days, decades, or centuries. It takes seriously the idea that there is a certain amount of indeterminacy in what we use our words to talk about—not the wild indeterminacy that says that ‘sad’ and ‘silly’ might reasonably be said to have sets of numbers as extensions, but a more tempered indeterminacy thesis that acknowledges that, absent interpretive interests and intent, there is just no saying whether ‘water’ as used by George II was true of samples of D2O. This means that same saying is to a certain extent a matter of interpretation. And so insofar as a sentence’s continuing to mean what it does is tied to its continuing to be a vehicle for saying what it presently does, whether a word preserves its meaning across time is to some extent a matter of interpretation.

I said that it was not unreasonable to think that because sentence meaning is coupled with what sentences say, shifts in saying power are indicators of changes of meaning. As I noted, one might go on to say that since what is said determines truth conditions, shifts in truth conditions must produce shifts in meaning. It is a short road from this conclusion to what Chapter 4 calls referentialism, the view that that within a linguistic community, diachronic constancy of a sentence’s character is necessary and sufficient for it to preserve its meaning. If by ‘meaning’ one means something like ‘determinant of reference and truth’, referentialism is obvious enough. But if one means something along the lines of ‘cognitive anchor of linguistic competence’, referentialism is much less obvious. Chapter 4 ends with a frankly skeptical discussion of referentialism about meaning-cum-anchor-of-competence.

I observed above that it’s natural to think that there must be a close connection between what a sentence means, what it is used to say, and the cognitive structures which realize a belief ascribable with the sentence. But just as I don’t think there is a one-size-fits-all-theoretical-needs notion of sentence meaning, so I don’t think there is a distinguished notion of what is (‘strictly and literally’) said by a sentence. It is reasonable to think that if we fix a group of speakers in actual and potential communication—be it all the English speakers in zip code 79104, the students in and teacher of this year’s iteration of Philosophy 147, or me and my wife—a sentence will have a ‘default interpretation’ relative to the group, one constructed from its semantic values and the ICG of its words in the group. Such a default interpretation is the starting point for interpretation, a reification of what someone from the group will have in mind when she begins interpreting the sentence’s use.1 Chapter 3 argues that this is one thing that might be identified as ‘what is said’ by a sentence S’s use. But there are many other candidates for this role. There is, for example, what the clause S contributes to determining the truth conditions of things like Jill said that S or Jack’s pretty sure that T. It strikes me as wildly implausible that in making such ascriptions we are very often to be understood as saying that Jack or Jill stands in an interesting relationship to a default interpretation of S as we and our audience use it. When I say, for example, that the Sumerians thought that Venus is a star, I am not suggesting that they made the sorts of presuppositions we make about Venus and the stars.

Chapter 5 spells out in some detail what I think is going on when we ascribe beliefs, sayings, and the like. It seems to me that what we do is to use our words as a representation—a ‘translation’, if you will—of a state or an utterance of the subject of the ascription. The correctness of an ascription like Jill thought Jack was at the top of the hill turns on whether its content sentence—the bit after ‘that’—is an adequate representation of one of Jill’s belief states, with standards of adequacy varying with the interests and intent of the speaker. I argue that, contrary to what you might think, thinking of ascription of belief and the like in this way doesn’t make it difficult to understand how

1 This way of putting things ignores contextual variability due to such things as demonstratives, gradable adjectives, and so on.

computers or non-human animals like wolves and wildebeests can have beliefs and make presuppositions (and so are in principle and practice able to mean things by behavior in the same sense in which our linguistic behavior does). The chapter argues against the idea that there is a close tie between some sort of (not merely referential) meaning of a sentence S and what we are saying about someone when we say that she said or believes or only just realized that S. It closes by using the account of attitudes and attitude ascription it sets out to defend some of the conclusions of Chapter 4 about meaning persistence.

My thought in this book is that we gain a certain amount of insight into language if we think of meaning as analogous to the population-level processes studied by biologists. But just how much is meaning change like biological evolution? Is it really a matter of something well described in terms of fitness and selection? This is the topic of Chapter 6, which suggests that some but not all of the processes that drive meaning change look to be like evolution via natural selection. That chapter ends with some discussion of interventions in the process of linguistic evolution, focused on Sally Haslanger’s idea of ameliorative philosophical analysis. One of the conclusions of this discussion is that thinking of meaning in the way developed in previous chapters makes the project of ameliorative analysis—as well as many of the projects clustered under the title ‘conceptual engineering’—appear much more sensible than it is otherwise likely to seem.

Quine and the Species Problem

One way to think about meanings has them static and unchanging, neither physical nor mental, abstract denizens of a ‘third realm’. This is more or less how Frege seemed to think of them. This, it seems to me, is a bad way to think about meaning.

Meaning is something our words, sentences, and (some of our) token mental states have. What each of our linguistic and mental states means is determined by a very large array of factors indeed: inferential relations, including tendencies to make inductive and abductive inferences; patterns of application and what contributes to determining them (e.g., prototype structures); tendencies to defer to others about matters of application; environmental and social relations; and so on. These determinants are not static: patterns of application change, prototypes evolve, we come to defer less (or more) to others, etc., etc. One could say that while the determinants of meaning shift, a meaning itself can’t change: like the number six or the Platonic form of Harmony, the meaning of ‘marriage’, the concept marriage, stays as it is, unchanging forever. One could say this, but it seems about as attractive as saying that the objects evolutionary biology studies—species, clades, and the like—do not change over time: species, like the number nine and the Platonic form of Justice, stay ever the same, even as the determinants of what species a population realizes shift. Quatsch

I have tried to cast my point in a way that is neutral as to whether the linguistic bearers of meaning are words and sentences of idiolects (the idiosyncratic language of a single individual) or words and phrases of public, shared languages. Of course, insofar as meanings are publicly shared, things passed on from mothers to daughters, the biological analogy just drawn is even stronger.

My goal in this and the following chapters is to convince you that there is indeed a rather strong analogy between biological entities (species, clades, population lineages) and linguistic and semantic entities (words, meanings, concepts, languages). This chapter makes a modest beginning on this. Its first sections review some obvious facts about language communities and speakers, some elementary facts about the ways biology thinks about species, and points out that there is indeed a prima facie case for thinking that things like word meanings are analogous to species. The chapter’s later sections argue that if we take the analogy at face value, we can embrace Quine’s conclusion in ‘Two Dogmas of Empiricism’—that there is no theoretically interesting notion of analytic truth, no sort of synonymy that can do epistemological work—while still thinking that the notion of meaning can carry a real theoretical load.

1. Private Language, Public Language

I assume that underlying each speaker’s linguistic ability is an internalized grammar. Such grammars are collections of mental representations that realize rules and procedures; these rules and procedures determine what the sentences of the speaker’s language are. Grammars involve a lexicon, a ‘mental dictionary’, that records broadly syntactic information about (basic) words—their syntactic category, phonetics, orthography, argument structure, ways in which they are abnormal or otherwise marked, and so on. Lexical entries are somehow interpreted—they are not senseless signs but have meanings that contribute to determining the meanings of the sentences in which they occur.

It is natural to think that lexical entries will change over time, if only because language is something that is learned over time. Children acquire a word and then expend a fair amount of effort to make their lexical entry similar in various ways to those of speakers in their surround: they refine and correct their pronunciation (smellow becomes marshmallow) and morphology (goed becomes went); they correct over- and under-extensions of predicates. It would be a strange theory indeed that insisted that every such change was the substitution of one vocabulary item for a new one.

Some, in an orgy of internalist fastidiousness, foreswear identifying the languages or even the words used by different individuals. They hold that the proper objects of linguistic study are individual grammars—the idiolects—of individual speakers. They say public languages are myths, since individual idiolects vary between parents and children, sibling and sibling; there is thus not a single set of sentences that constitutes the sentences of ‘the’ language spoken by the members of a single family, much less such a thing as ‘the’ grammar or ‘the’ language they speak.

Idiolects do indeed vary from individual to individual, and we can grant that it is more than just a rarity for parent and child or sibling and sibling to literally share an idiolect. That admitted, there is surely something significantly amiss in the idea that linguistics, thought of as the study of human language, is only concerned with individual idiolects. Languages, after all, are vehicles of communication. And it is hard to see how they could be vehicles of communication within a population—a family, a fourthgrade class, the readers of The New York Times—unless there were mechanisms in place that coordinated the different idiolects in the group so that what a speaker utters is reliably identifiable and thus understandable at some level quite independently of the identity of the speaker and the interpreter, independently of the particulars of contexts of use and interpretation.1 Whatever differences there may be between Mom’s, Dad’s, Brother’s, and Sister’s grammars, there is surely a coordination between their lexicons that links individual entries for the noun ‘stranger’: Dad uses his ‘stranger’ entry, SD, to interpret the words that are generated by Mom’s, Brother’s, and Sister’s

1 The sort of understanding I have in mind is not identifying ‘what is said’ by an utterance but what we would pre-theoretically call ‘knowing what sentence was uttered’, something that is normally necessary but usually not sufficient for ‘knowing what was said’.

‘stranger’ entries SM, SB, and SS; each of the other three use these entries to interpret the tokens generated by the others’ entries. Each interprets the others as producing the same word, and the word each interprets the others producing is the word the others interpret him as producing. Something similar is true of larger phrases, of course. Part of what makes the child’s grammar a language is that it is a medium for communicating with those who are linguistically connected via this sort of coordination with the child; part of the study of language is the study of such linguistic connection, of what underlies, reinforces, and disrupts it, of how it evolves over time. If this is correct, then perhaps there is, internalist objections notwithstanding, something to the idea of a public language. Suppose, for example, that there is a more or less determinate, more or less robust relation lexical entry e is at time t coordinated with lexical entry e’ that connects the entries in different speakers’ lexicons, a relation that (more or less) reflects when speakers do and do not understand one another: save in exceptional circumstances, I interpret your utterance of a word correctly just in case the entry your utterance tokens is coordinated with the entry I use to interpret it. If this relation is (more or less) an equivalence relation, we might understand talk about common vocabulary as shorthand for talk about relations of lexical coordination. And if such coordination projects up from the lexicon to more complex phrases so that it determines a ragged equivalence relation on phrases in different individual grammars, we might be able to understand talk about common languages as shorthand for talk about this sort of coordination. Whether it’s reasonable to think that something resembling the everyday notions of (public language) word and phrase can be so constructed is an issue to which I will eventually return.2

2. Species and Meanings

There are analogies between biological objects—population lineages, species, genomes, and such—and various linguistic objects—languages, vocabularies, individual words, their meanings, and the like. (Public language word) meanings being a kind of concept, it will be no surprise that these analogies extend to concepts. The analogies are useful because they suggest useful ways to think about linguistic and conceptual continuity. In particular, they help us see how it might be that while Quine was substantially correct in his pessimism about analyticity and conceptual truth, he was—or at least might have been—wrong to conclude that something like the ordinary notion of meaning is unable to do serious theoretical work.

Before looking at analogies, let’s review some facts about species and speciation. The currently dominant accounts of species take them to be parts of population lineages— parts, that is, of sequences of populations related by descent and ancestry. Not just any such sequence is a species—we’re conspecific with our grandparents but we aren’t conspecific with every ancestor of the chimpanzee, though there is a tree of descent (a phylogeny) that has the chimps and us descending from common ancestors. There is

2 More on the notion of coordination in Chapter 4.

considerable controversy as to what ‘the right’ species concept is; the species problem is the puzzle of whether there is a notion of species that can do the theoretical work demanded by talk of species in various branches of biology—systematics, evolutionary biology, ecology, population genetics, and so on.

There seem to be something in the neighborhood of two dozen characterizations of species knocking about, and little sign of a great synthesis that would significantly narrow this number.3 Some take species to be something like populations distinguished from others by certain evolved features—a new species arises when a particular set of distinguishing features arises (eleven-toed, tripedal, blue feathers .); the species is the sequence of populations with these features descending from the founding population. Others take them to be populations united by one or another (usually relational) property: the ability to interbreed, geographical or ecological range, fecundity of offspring, etc. Even if—and it remains very much an ‘if’ in evolutionary theory—speciation is usually relatively abrupt in geological terms, the fact remains that, looking at a population generation by generation, it can be difficult or impossible to say in a principled way where one species leaves off and a new one begins.4

While there’s a good deal of variation across species concepts, there’s also some unity. On most accounts, species are certain population lineages whose stages5 (i) tend to reproduce themselves in ways that preserve certain kinds of synchronic cohesion in the succeeding population, and (ii) are subject to diachronic change over generations of reproduction that can result in ‘diachronic lack of cohesion’ between stages of the lineage in which the species occurs. They are lineages which (at each time at which some population realizes the lineage) are unified—there is enough commonality in the genomes of a species’ individuals that we can speak of a common genetic structure with common, functionally defined areas. But they are also diverse: variants of genes (alleles, in biospeak) occur at particular loci in the genome across the population; while every (normal) individual has a version of some trait (eye color, height as an adult, etc.), the form of a trait’s realization varies across the population. As one population descends from another, new forms arise and spread through the population; some traits whose past realizations varied across the population see a particular realization become fixed in successor populations. Enough ‘diachronic lack of cohesion’—enough difference between one segment of a lineage and a later segment—implies that speciation has occurred. What varies across species concepts is (in good part) the sort of cohesion needed for a population in a particular temporal interval to form a stage of a species. On some accounts, it is morphological traits originating in some ancestor that separate

3 Richards (2010) cites Mayden (1997) as claiming that there are more than twenty species concepts in use among biologists. Both Richards (2010) and Hull (1997) give useful discussions for philosophers of the range of species concepts.

4 There are notions of species that come close to untying the idea of a species from the idea of descent, with species defined in more or less observable terms. That said, it is not clear that anyone, not even Aristotle or Linnaeus, really had a totally ahistorical notion of biological species. Again, see Richards (2010) for an illuminating discussion.

5 Think of the stages of species as the populations that constitute them at particular times. The use of ‘stage’ here is not an attempt to suggest that species or languages are ‘four-dimensional objects’.

the species from all others; on other accounts, it is the potential to interbreed; on others, it is a matter of being part of a single gene pool; on others, something else.

There are some who are skeptical that species ‘reflect an important ontological divide in nature’ (Ereshefsky 1999, 286). Some claim that the soritical way in which evolution occurs makes species non-starters as serious theoretical entities. On one version of this view, what is biologically real are lines of descent in which populations diverge in ways passed on by descent, ways driven toward fixation by selection; species are nothing more than a gerrymandered and incomplete way the folk and the biologist have of describing parts of this reality in which they are interested.

It is striking how much of all this seems to be reflected in the linguistic world.6 Think of a population that we would describe as sharing a common language—the residents of Long Island, say, who are in the habit of using English to talk to each other. The grammars that describe the idiolects these people speak are united. They share large swatches of vocabulary and a grammatical template (for example, all these idiolects are Subject/Verb/Object languages, not Verb/Subject/Object languages). But there is also diversity in the community: there is individual variation in morphology, orthography, and conceptual structure in individual realizations of the lexicon; the grammars differ on some rules, morphology varies, and so on. As in the biological case, the (lexical and grammatical) unity that underlies variation in such a population is critical for its (linguistic) perpetuation: one generation typically transmits the lexicon and grammatical template that unifies its linguistic community to the next, (more or less) insuring that the next generation can communicate with one another (and with the previous one).

Of course languages, lexicons, and individual words—like species—evolve. As one population ‘reproduces’ its language in the next, new words arise, old words have their meanings changed, phonology shifts, grammatical rules may be modified, and so on.7 As is the case with species, some of this evolution will be quite gradual: successive generations are able to fluently communicate with one another, just as successive generations in a population lineage are (counterfactually and in principle) able to interbreed, have fertile progeny, share a system for recognizing mates, etc. As is the case with species, even when abutting generations enjoy the sort of cohesion that would drive the observer to classify them as speakers of a single language, the soritical ways of linguistic change, given enough time, will lead to a diachronic lack of cohesion so great that no one will say that ancestor and descendent populations speak the same language, even though the languages they use are related by descent.8

6 A good discussion that recognizes the possibility of an analogy between population genetics and linguistic descent is Lightfoot (1999).

7 There are of course major disanalogies between biological and linguistic evolution. For example: Linguistic evolution is in good part Lamarckian, with ‘acquired traits’ often becoming fixed in a language. Even granting that there are some Lamarckian processes in biological evolution, they are presumably nowhere near as important biologically as they are linguistically.

8 The same sort of thing can occur synchronically in both the linguistic case and the biological one. So-called ring species are made up of populations that abut one another, with the abutters being able to interbreed and produce fertile progeny, although the populations at the ends of the ring are unable to. And

There are those who are skeptical of the reality—or at least the theoretical interest—of public languages, shared vocabularies, and word meanings. Some point to the soritical way languages change across geographic regions or times; some object that if there’s no learnable grammar, there’s no natural language, but there is no reason to think that a grammar that would generate just the sentences that ‘speakers of English’ would recognize (under idealization removing finite limits on processing) as sentences of English.9 It is plausible that the worry that there is ‘no important ontological divide’ between public languages as the folk and philosophers think of them and more encompassing linguistic taxa is at least as well grounded as the worry that there is no important ontological divide between species and other segments of population lineages.

3. Quine’s Argument in ‘Two Dogmas’

Some of Quine’s worries about the notion of meaning—in particular, the skepticism he voices in ‘Two Dogmas of Empiricism’ (Quine 1951)—can be seen as kindred to the skepticism of those who think there is no principled distinction between species and other phylogenies. Quine made at least two important points about analyticity and conceptual change in ‘Two Dogmas’. One was about rational constancy in belief: Quine argued that one could rationally continue to accept a sentence or statement ‘come what may’. He was led to this conclusion by reflecting on how observation impacts theory. One can, and science often enough does, hold on to a hypothesis in the face of evidence that it makes incorrect predictions by discounting that evidence. As Quine put it, ‘our statements about the external world face the tribunal of sense experience not individually but only as a corporate body’ (Quine 1951, 41). If one accepts this, it is natural to think that evidential connections are not essential to the meaning of a sentence: if I can rationally continue to accept the statement made by a sentence no matter how the evidence goes, then revising a sentence’s evidential connections doesn’t—or at least needn’t—change the sentence’s meaning.

Quine’s second point was that no sentence or statement was immune to rational revision. At any time, we accept certain claims—they make up our ‘total theory’—and we take the field of claims to stand in broadly logical and evidential relations to one another and to experience. But there is nothing sacrosanct or meaning-constitutive about these relations: considerations of, for example, theoretical economy or unification could in principle lead us to revise logical laws, but it would be a mistake to see this as simply ‘changing the meaning’ of the logical particles. Theory revision is not in and of itself meaning change.

Of course one could, out of love for the sound of the sentence S, tenaciously accept it come what may by redefining its words; one might, for a lark, redefine ‘or’ to mean ‘and’

more or less gradual variation in dialects across a region can produce incomprehension between speakers on the edges.

9 Both of these complaints can be found in Chomsky (1980).

and consequently revise one’s opinion about the truth of ‘Bob is here or Bob is not here’. Some qualification is needed in Quine's claims, presumably something like this: one may rationally accept any sentence come what may/revise whether one accepts any sentence without there being good reason to say that one means something different by the sentence than what one formerly did.

It would, of course, be useful to have some sort of a story about when one does or does not have good reason to say that a sentence has changed its meaning. Quine doesn’t provide one, but one can imagine what one might say on his behalf. At any time, the way we use our words gives them a particular inferential role. Our linguistic activity embodies presuppositions about the world as well as assumptions about how others will use their words when they speak. The inferential role and presuppositions accompanying our words determine how we use our language as a tool for inquiry and communication.

In order for there to be reason to say that a sentence has changed its meaning in virtue of some change in use or a user’s mental states, there has to be a ‘lack of cohesion’ between how things were before the change and how things are afterwards. Changes in inferential role or in presuppositions that result in fluid conversation being stymied or in the role of a sentence in inquiry being radically revised can be sensibly called a change in meaning.

Suppose a change in a speaker’s use of a sentence (or in the mental states reasonably held to contribute to one’s understanding of the sentence) doesn’t cause (actual or potential) interruption in the fluidity of communication—the change in the speaker’s use, that is, does not result in a loss of the feeling-of-understanding-without-need-ofcorrection-or-reinterpretation on the part of audiences when the speaker uses the word. Suppose further that it has a relatively minimal effect on the role of the sentence in inquiry and on the mass of mental states that contribute to linguistic understanding. Then the change doesn’t give one good reason to think that the sentence means something other than it did before the change; one has good reason, simply given the change, to think its meaning is constant.

This is not an unreasonable criterion. If we accept it, it seems we can spin Putnamian stories that show that putatively analytic sentences—‘cats are animals’, ‘pencils are inanimate objects’—can be rejected without the rejection occasioning a change in meaning (Putnam 1975, 1986). After all, if we did find ourselves in a Putnamian scenario—cats turn out to be robots from Mars, pencils turn out to be disguised worms—we would naturally describe them as scenarios in which . . . cats turn out to be robots from Mars, pencils turn out to be disguised worms. We would feel our use ‘cats are (not) animals’, ‘pencils are (yuck) worms’ after our discovery cohesive with our use before. We would find the suggestion that we had ‘changed the meaning’ of our words at best odd.

I cast Quine’s point as an epistemological one: any statement-sized change in what one accepts may occur without one’s having reason to say that one has changed the meaning of some word (used in making the statement). How do we get from the

epistemological point to the claim that Quine is often thought to have argued for—that the relevant changes aren’t changes in meaning?

It is Quinean at least in spirit to argue so. What determines the meaning of a word or sentence is relatively ‘big’. Meaning is determined by inferential relations, including tendencies to make various sorts of inductive and abductive inferences, patterns of application and things that contribute to determining them (e.g., prototype structures), tendencies to defer to others about matters of application, environmental relations, and so on. But the sorts of statement-sized changes that Quine has in mind in ‘Two Dogmas’ are for the most part relatively ‘small’. Even rejecting the claim that cats are animals needn’t have all that much of an impact on how one uses the terms in ‘cats are animals’, or on whether others understand you. It needn’t have all that much of an impact in that it may leave a great deal of what is meaning-determinative for one’s words or concepts—inferential relations, inductive patterns, patterns of application and deference, environmental relations, and so on—more or less unchanged. But whether it is correct for x to say that her words mean the same as y’s, or that she and y share such and such concepts, is determined by the extent of overlap between what is meaning-determinative for x and y’s words or concepts. Since it would generally be absurd for x to say, when there is only a small failure of overlap between x’s words or concepts and y’s—a small failure that doesn’t in any way impede fluid communication— that x and y don’t mean the same things by their words or that they fail to share (the relevant) concepts, we may conclude that a person who rejects putatively analytic statements like the statement that cats are animals does not thereby change the meanings of the words in the sentence.

I think this sort of argument—I’ll call such an argument a gradualist argument—is basically on target. What follows are some comments on it, along with some comparisons with the case of biological entities like species.

(a) I understand Quine’s claims to have a modal element: no statement is immune to revision in the sense that there are (possible) situations in which one could reject the statement without thereby changing the meanings of the words one uses to make it. To say this is not to say that in every situation in which one rejects the statement the meanings of the relevant words remain constant. Dramatic examples are the most obvious here. Suppose all at once I decide that cats are not animals because I have been misidentifying them, foolishly deferring to my parents and others about which things in the environment are cats: actually, I decide, cats are ubiquitous, as ubiquitous as protons. If I really accept this, I am not using ‘cat’ to talk about cats (or anything else); if this madness is unaccompanied by some concepts coming to play a role more or less like the role my cat concept used to play for me, I have lost that concept.

It seems to me that similar things should be acknowledged about speciation. No small genomic, phenotypical, geographical, or ecological change in a population is intrinsically, of necessity speciating. Which is not to say that there might not be reasons to point to a particular change (or relatively small group of changes) or a particular

event as one that marks a species boundary. Geographic isolation which halts the flow of genes between subpopulations and leads to evolutionary divergence is a natural place to draw a species boundary. But this is very much a contingent, historical matter. It is not the event of separation itself that causes speciation. Suppose P actually splits into subpopulations P1 and P2 at t, and this leads to speciation. If P had split into P1 and P2 at t but shortly thereafter its member populations were reunited (a defect in the dam that separated the populations causes the dam to collapse, say), no speciation would have occurred. Much the same could be said about genetic, phenotypical, and ecological changes: whether a particular such change marks a good boundary to draw a line and say that the line non-arbitrarily marks where speciation has occurred is very much a matter of the historical context in which the change occurs; it is not, unless the change is massive, intrinsic to the change itself.

(b) A familiar idea from the literature on vagueness is that when a predicate’s range of application generates sorites series, the predicate’s application will vary with the context. Confronted with a sequence of patches that very gradually change from orange to yellow and asked to judge of each patch in succession whether it is orange, yellow, or some intermediate category (‘not sure’, ‘indeterminate’, whatever), an observer will start judging patches orange and at some point begin judging them yellow; when the switch occurs, she will then be inclined to reverse her judgment on the immediately preceding patches. (‘Yes, I know I said that one before was indeterminate, but if this one’s yellow, then that one’s yellow, and this one is yellow.’) Given that there is a close tie between the judgments of the competent user of an observational predicate like ‘yellow’ and its correct application—the applications the competent user is prepared to stick by are ceteris paribus correct—this strongly suggests that in the course of evaluating the patches in the series, the application conditions of ‘orange’ and ‘yellow’ as the speaker uses them change.10

It is obvious that in such cases the speaker does not undergo conceptual change— she does not lose one concept of yellow and acquire a new one—or begin using a word with a new meaning which just happens to be spelled like her old word ‘yellow’. True, we might mark this sort of contextual change of use by saying, ‘well, at that point [when the speaker reverses judgment about earlier cases that she did not judge yellow] she meant something else by “yellow” than before’. Pre-theoretical talk about meaning is a pretty blunt instrument, and we do tend to label shifts in correct application as a ‘change in meaning’.11 But even those who are inclined to say this recognize its awkwardness in this sort of case, and allow that in an (in the) important sense the woman does not change what she means by ‘yellow’ as she revises judgment about the cases in the series.

10 This sort of point was first emphasized in Raffman (1994). It has been endorsed and developed in various ways by Graff (2000) and Soames (1999), among others. The point is orthogonal to the question of whether the relevant predicates are bivalent.

11 A good deal of care is required to state this correctly. Chapter 4 takes up relations between various notions of meaning and reference.

If we agree with this story about the color concepts, we will say that they have a limited ‘perspectival relativity’: within a certain (somewhat vaguely delineated) area, users of those concepts have a certain amount of leeway as to what is and what is not their correct application. This perspectival relativity doesn’t render the concepts ‘defective’. For most of the everyday, non-technical jobs we call upon these concepts to perform, their contextual shiftiness is irrelevant; when it matters, we can work around it via stipulations. Ditto for other soritical concepts that may have contextually shifting extensions. A term or concept may be soritical and consequently have shifting boundaries while still being perfectly useful for certain practical or theoretical purposes.

We should apply this moral quite generally to our concepts of particular species, languages, word meanings, and concepts. The concept yellow has a certain limited perspectival relativity. It is a ‘rule of proper usage’ of the concept yellow that if x is observed in favorable circumstances and competently judged yellow, then x and whatever is indistinguishable from it color-wise is yellow.12 Something similar is true of species concepts like Fulvous Whistling-Duck, language concepts such as American English, and concept concepts like the concept book. If the community of biologists competently judges (knowing all the relevant facts) that a certain population P is a single species and that populations ‘next to it’ in the population lineage(s) in which P occurs are conspecific, those judgments are acceptable and may be counted as correct. If a linguistic population is able to converse fluidly with the linguistic population that spawned it and with the linguistic population it spawns, its judgment that it speaks the same language as those neighboring it in its linguistic lineage is generally correct. If a population makes a small adjustment in what is meaning-determinative for a word— where dropping the claim that some cats are animals in a Putnam scenario is small in the relevant sense—but does not feel that it has done anything more than correct an erroneous belief, their judgment that they ‘still mean the same thing’ with the relevant word is ceteris paribus correct.

Note that holding this does not imply that the relevant notion is of no theoretical utility. Species are fuzzy around the edges. Those ‘in the thick of evolution’ might permissibly—and thus correctly—apply a species concept to temporally nearby populations in ways that someone who could survey the course of history could reasonably criticize. This does not show that the notion of a species is unfit to carry explanatory weight in various fields in biology. Ditto for the various linguistic notions.

(c) One might worry that the gradualist argument, like many a sorites argument, proves too much.13 The argument comes perilously close to suggesting (for example) that meaning is indefinitely plastic. We can, after all, imagine a soritical shift in the various factors that determine a word’s meaning: on Monday we replace a prototype that guides the user in applying the term; on Tuesday another; and so on through the

12 Competence requires that in favorable circumstances one’s judgments do not stray too far from paradigm examples.

13 The worry is suggested by comments by Alex Byrne about a kindred argument.