3

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

© Oxford University Press 2020

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

CIP data is on file at the Library of Congress ISBN 978–0–19–005230–0

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

Printed by Integrated Books International, United States of America

To my teachers 子曰:「溫故而知新,可以為師矣。」

1. Paradoxes of Freedom: Modern

1.2. “From Status to Contract”: Myths and Histories of Authority’s

1.3.

1.4. Transformations of “Dependence”

1.5.

2.

2.4.

2.5.

2.6.

3.6.

3.7.

3.8.

4. The Confucian Dào: Mastery as the

4.1.

4.2.

4.5.

4.6.

4.6.1.

4.6.2.

4.6.3.

5. Dependence, Autonomy, and the Varieties

5.1.

5.2.

5.3. Subordinate

5.4.

5.5.

5.6.

6. Dreaming of a Meritocracy, Grappling

6.1.

6.2. Realism, Idealism, and “Dark Consciousness”

6.3.

6.4.

6.5. The Hierarchies of “Virtue” and “Position”

6.6.

7.

7.1.

7.2.

7.3. Autonomy

7.3.1.

7.3.2.

7.3.3.

7.4.

7.5.

7.6.

Acknowledgments

This book has been gestating for a long time, and I have incurred many debts. I thank colleagues and friends at Indiana University, and remain delighted to be a part of that intellectual community, especially our vibrant and collegial Department of Religious Studies. I have learned much from participants in the EPP colloquium, the Chinese reading group, and the Global and Comparative Approaches to Religion, Ethics, and Political Theory seminar, among other groups. A number of people have read large parts of the manuscript, and it was significantly improved by their suggestions and questions— notably by Michael Ing and P. J. Ivanhoe, who both gave me extensive and helpful comments, as well as Ryan Collins, Aurelian Craiutu, Oliver Eberl, Constance Furey, Bojue Hou, Naiyi Hsu, Hui Jiang, Mihee Kim-Kort, Simon Luo, Aolan Mi, Patrick Michelson, Rick Nance, Gheorghe Pacurar, Meng Zhang, and Kuangyu Zhao. I also very much appreciate the comments and suggestions from two anonymous reviewers for Oxford University Press, as well as the brisk professionalism of my editor, Peter Ohlin. Gretchen Knapp’s editorial help has been invaluable. I am particularly grateful to my friend and colleague Michael Ing, who has cheerfully endured almost infinite discussion of points large and small related to the ideas here, supported me throughout, and taught me much. And I am thankful for many delightful and stimulating talks with Rich Miller about ideas that eventually found their way into this study.

Beyond those already mentioned, I have learned from conversations related to the book with, among others, Steve Angle, Cheryl Cottine, Susan Blake, Nick Vogt, Rui Fan, Bharat Ranganathan, Hao Hong, Ruilin He, Lisa Sideris, Winni Sullivan, Kevin Jaques, Huss Banai, Jeff Isaac, Kate Abramson, Marcia Baron, Gary Ebbs, Bob Eno, Chuck Mathewes, Jeff Stout, Gustavo Maya, Eric Gregory, Liz Bucar, Grace Kao, John Kelsay, Barney Twiss, Aline Kalbian, Martin Kavka, Jock Reeder, the late Wendell Dietrich, Hal Roth, Jung Lee, Lee Yearley, Bruce Grelle, Nigel Biggar, Joshua Hordern, Chip Lockwood, Amy Olberding, Ted Slingerland, Eric Hutton, Jack Kline, Justin Tiwald, David Wong, Bryan Van Norden, Michael Puett, Yong Huang, Tongdong Bai, Robin Wang, Michael Slote, Erica Brindley, Karyn Lai,

Alexus McLeod, Doug Berger, Benjamin Huff, Bryan Hoffert, Jud Murray, Erin Cline, Frank Perkins, Tao Jiang, On-cho Ng, Keith Knapp, Christine Swanton, Tim Dare, Brad Wendell, Sophie Grace Chappell, Steve Macedo, Melissa Lane, Alan Patten, and Leora Batnitzky. I have presented versions of parts of the manuscript in several venues, including at the Midwest Conference on Chinese Thought; I would like to thank participants on all these occasions for their helpful responses.

Part of section 1.2 appeared previously in “Mastery, Authority, and Hierarchy in the ‘Inner Chapters’ of the Zhuāngzǐ,” in Soundings: An Interdisciplinary Journal 95.3 (2012): 255–283. Parts of chapter 3 appeared in an earlier form as “Virtue as Mastery in Early Confucianism,” in the Journal of Religious Ethics 38.3 (September 2010): 404–428. I thank the editors of both journals for allowing me to reuse and adapt this material.

I gratefully acknowledge timely financial support from the Indiana University College Arts and Humanities Institute, the Chiang Ching-kuo Foundation, and the Indiana University Office of the Vice President for Research, which gave me needed time to focus on research and writing at various points.

I am especially grateful for my family, who have taught me almost all that I know about the real human basis for this book. In particular I thank my wife, Kirsten Sword, for many fruitful conversations that originally stimulated much of the research for this book, for discussions and help with relevant historical scholarship, and for timely reading and editorial aid. My children, Elena and Rowan, have grown up as I wrote this book, and have, perhaps without meaning to, taught me a great deal about both mastery and dependence along the way.

Conventions

I use the Pinyin system of Romanization throughout. Nevertheless, when I include Chinese characters in the text I use the traditional complex forms. Exceptions to the use of Pinyin include scholars’ names when they are written in some other form of Romanization, such as Hao Chang (張灝). For contemporary people, I follow the English-language rule of putting personal names first and surnames second, even for Chinese names. For figures from early China, my preferred practice is to refer to their standard honorific titles in Pinyin, e.g., “Kǒngzǐ” instead of “Confucius,” and “Mèngzǐ” instead of “Mencius.” I refer to other well-known figures from the tradition according to their Chinese names, in a Chinese order (e.g., Zhū Xī). I capitalize Rú (儒) when referring to the people, ideas, or tradition of thought and practice known commonly in the West as “Confucian” or “Confucianism,” although in this case, for variety, I use both “Rú” and “Confucian” interchangeably. With regard to the word dào 道, a “path” or “way,” I keep the word lowercase when I refer to a practice tradition such as archery, or use the word in a generic sense; when capitalized, Dào refers specifically to the Confucian “Way” of life as a whole.

For works cited, I use the author-date system in both the endnotes and the bibliography, and follow the conventions described in the Chicago Manual of Style, as amended by Oxford University Press. For early Chinese primary sources, I generally refer to the Chinese University of Hong Kong Institute of Chinese Studies’ Ancient Chinese Text Concordance Series 《 香 港 中 文 大 學 中 國 文 化 硏 究 所 先 秦 兩 漢 古 籍 逐 字 索 引 叢 刊 》, unless otherwise noted. When citing specific passages in the texts, I refer to the relevant concordance in the following format: “chapter/page/line.” However, I also frequently cite whole passages from the Analects and Mèngzǐ in accordance with the traditional style of “book.passage” for the Analects (e.g., 12.1) or “chapter-division-passage” for the Mèngzǐ (e.g., 2A2). For the Xúnzǐ, I follow Knoblock’s chapter and section scheme for citing whole passages (e.g., 19.1), because this can be easily cross-referenced with Hutton’s excellent translation or with Knoblock’s. For the Lǐjì, I have used the ICS Concordance (Lau and Chen 1992) as well as the Chinese Text Project’s electronically published text

(http://ctext.org/liji), which is based on a version of the widely available Táng dynasty edition, the 禮記正義 (see Lü 2008). Citations to the Lǐjì are in the form: chapter.CTP section.ICS section/ICS page/line(s). For an English translation, see Legge (1885). Translations are my own unless otherwise noted. I do refer to other editions at times, especially when discussing textual or interpretive issues. I abbreviate the Analects as LY (= Lúnyǔ 論語), the Mèngzǐ as M, and the Xúnzǐ as X.

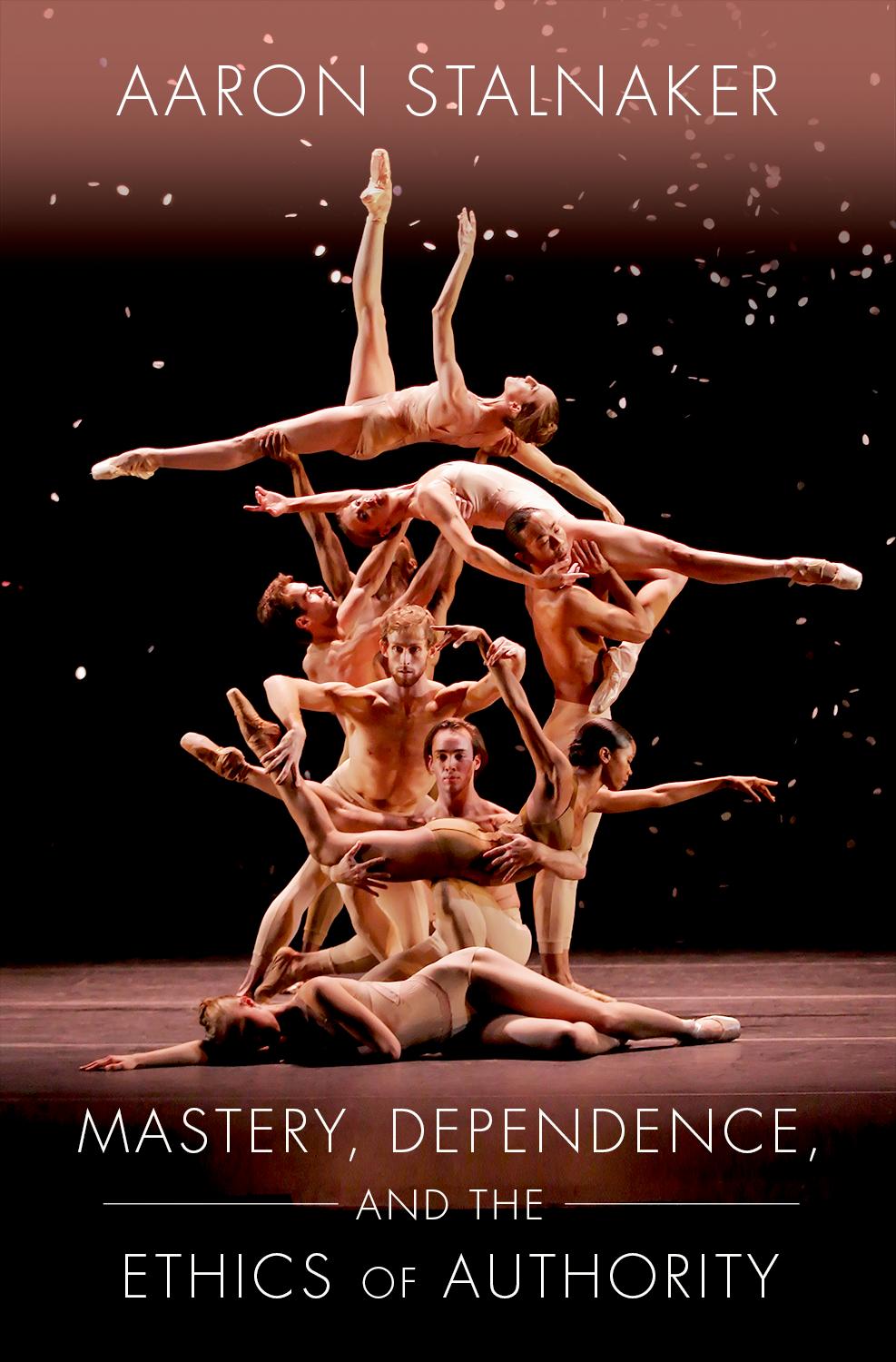

Mastery, Dependence, and the Ethics of Authority

1 Paradoxes of Freedom

Modern Western Difficulties with Authority and Dependence

1.1. Introduction

What are the proper roles of authority in a life well lived, and in flourishing communities? How should we understand the relation of personal autonomy to the authority of experts and other practical authorities, such as political leaders? How many different kinds of authority are there, and how should they be understood? This book addresses these and related questions, especially regarding various kinds of dependence, by means of a sustained encounter with a potentially surprising source for new insights: classical Confucian ethics and political theory.1 Early Rú 儒, or “Confucian,” texts, especially those memorializing Kǒngzǐ (“Master Kǒng” or “Confucius”), Mèngzǐ (“Master Mèng” or “Mencius”), and Xúnzǐ (“Master Xún”), develop a set of responses to these questions that are powerful, subtle, and in certain important respects very attractive even today. To begin to see why early Rú ideas can help us, we need first to take stock of common conceptions of authority, and learn to see these in relation to views of dependence.

Contemporary Westerners are heirs to a deeply conflicted heritage of ideas about authority and personal freedom. The question of what makes an authority legitimate has been intensely debated for several centuries in the West, and with renewed vigor in political philosophy and associated fields since the upheavals of the 1960s. Philosophical discussions of practical authority from that time forward have generally been framed to address the “anarchist challenge,” which questions the legitimacy of all governmental authority, seeing it as an unjustified infringement on individuals’ autonomy. This sort of root-and-branch rejection of authority often accompanies seemingly progressive hopes for a liberated future without hierarchies of any kind. But is it really possible, and desirable, to do without authority? Let me briefly

Aaron Stalnaker. Mastery, Dependence, and the Ethics of Authority, Oxford University Press (2020). © Oxford University Press.

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780190052300.001.0001

point out some common but conflicting intuitions about different kinds of authority.

Contemporary people readily accept the value and even necessity of master teachers of skillful arts such as violin performance or playing basketball. When we want to learn to play the piano, for example, we arrange to learn from an expert teacher of the art; we would rightly consider it misguided to try to learn to play without such training. Similarly, most contemporary people would, upon reflection, agree that children need good parents or parent-surrogates to raise them, and in the process exercise some forms of authority over them.

For adults, however, the positive value, and perhaps necessity, of various forms of authority is more controversial. For example, many are more suspicious of the idea that there might be ethical experts who are genuinely wiser than the rest of us, better able to live life well. This idea seems anathema to contemporary convictions that all people are morally equal, especially if such experts may claim more respect or power than others. If such ethical “masters” exist, what teaching roles they might play in human development, if any, is the subject of profound controversy and much principled skepticism. If ethical experts were to try to teach someone else how to be good, would that not override the student’s own judgment at times and thus threaten his or her moral autonomy? This dissonance leads to serious questions. In what ways might people need to depend on others to learn about and cultivate virtue? What role does autonomy play in such personal formation, both as goal and as means?

A set of concerns parallel to those just mentioned about ethical experts can also be raised concerning those involved in the world of politics. Just as there is principled skepticism regarding ethical expertise, there is widespread skepticism regarding the existence of political experts, by which I mean people who actually are much better than the rest of us at leading social groups and exercising executive authority.2 Westerners generally find that Lord Acton’s pithy 1887 thesis, “Power tends to corrupt and absolute power corrupts absolutely,” expresses an obvious truth.3 As a matter of democratic prudence we should therefore expect anyone who holds high office to be repeatedly tempted to disintegrate morally, and thus corrupt whatever political expertise they might once have possessed, gradually approximating the pseudoexpertise of contemporary campaign consultants and “spin doctors” willing to shill for anyone. On these premises, how one might actually become a wise

political leader begins to seem even more mysterious than how one might become a good person.

The questions I raised at the beginning about authority and autonomy are timely ones for contemporary Westerners, as well as perennial and universal issues of human social life. Historically speaking, many intellectuals in the West (and elsewhere) understand themselves as heirs to the “flight from authority” inaugurated by the Protestant Reformation and deepened by the Enlightenment and associated political revolutions. And the social life of Western democracies took a dramatic turn from the late 1960s forward, as large numbers of young people rebelled against existing authorities and the institutions that gave them power. A conservative backlash ensued in the 1980s, and the shape of that confrontation has continued to define American politics in particular, for better and for worse. At the same time, economic and social stratification has gradually increased to dramatic levels not seen since the Gilded Age in the late nineteenth century.

Many factors have contributed to these trends, and they are not easy to unravel. As the field of sociology has developed, it has arguably taken social stratification, whether by class, race, gender, or other forms of status, as its primary focus.4 Understandably, sociologists tend to be skeptical of these forms of status and wealth differentiation, often finding them to be unjustified— in contrast to some economists and political thinkers. Defenders of wealth inequalities often insist that what we now see are the natural results of free and dynamic competition, in which there will always be winners and losers. From either side, debate tends to hinge on ideas about human equality and the nature of liberty, and how they ought to interact. Philosophical and religious thinkers have provided the egalitarian normative underpinnings of both the sociological research program and the debate among social critics about justice.

This study focuses on these fundamental normative presuppositions. In this book I argue that an excessively narrow focus on coercive authority, combined with unwarranted inferences from laudable commitments to moral equality, have led contemporary thinkers astray on authority, dependence, and social ethics more generally. We can do better, by refining our political and ethical commitments so that they might direct us away from the paradoxes of coercive authority in a free society, toward more fine-grained understandings of different forms of hierarchy, authority, and merit, as well as of our dependence on and responsibility to each other. If we can more precisely distinguish legitimate exercises of authority from objectionable

domination, we will be better able to evaluate and reform, where needed, a wide range of current social practices structured by authority relations, including government, academia, family life, and even the business world.

The rest of this chapter proceeds as follows. In section 1.2 I briefly discuss the intellectual history of the modern transformation of authority alluded to earlier, in order to suggest the deep roots of contemporary convictions. In section 1.3, I begin to engage contemporary debates about autonomy and authority, drawing on liberal, republican, and feminist analyses. There I examine how the tendency to understand universal human dignity as conferred by individual autonomy is often used to justify the politics of antidomination that structure many discussions of political authority. (I return to these issues in greater depth in section 7.3.)

Recent analysts almost always understand such authority, to borrow Max Weber’s concept, as Herrschaft, or “imperative control”: the socially legitimated power to command obedience, correlated with a duty requiring subjects of that authority to obey (Weber 1947, 152). Given our liberal and democratic heritage, such authority generally appears suspicious, something to be limited as much as possible.

The legal and political philosopher Joseph Raz has articulated the most influential contemporary philosophical analysis of authority in this sense. I address his theory and the debates it has spawned, in part because it is in many ways an incisive discussion of the subject, and in part because it shows how relevant, and in certain key respects distinctive, are early Confucian analyses of authority and its relation to autonomy.

We can see the distinctiveness of Confucian views in two main areas: first, they reject the idea that submission to authority is automatically threatening to individual autonomy; instead, they think submitting to the right sort of authority in the right way is the best path to cultivating autonomy. And second, they insist that the human condition is one marked by numerous interacting forms of dependence, which are not only ineradicable, but in many ways good. On a classical Confucian view, it is natural, healthy, and good for people to be deeply dependent on others in a variety of ways across the full human life span. Fully unpacking these points will take some time, and will require care to avoid falling into common conceptual confusions between differing senses of “authority,” “dependence,” and “autonomy,” among other key ideas.

After addressing authority as imperative control, and sketching the contours of current debates over legitimate authority, this chapter moves

on to less familiar territory. In section 1.4 I summarize and discuss the implications of historians’ work on the history of dependence in the modern West to add needed nuance to intellectual historical discussions of changing ideas about authority over this period. And in section 1.5 I discuss the resolute anti-paternalism of thinkers like J. S. Mill and Isaiah Berlin, whose ideas have done much to provide intellectual cover for a libertarian agenda that seeks to minimize state support for cultivating “positive freedom” or capabilities among the general populace. With these preparatory analyses of the current state of debate in place, I close the chapter with a preview of what contemporary Westerners should learn from the early Confucians about authority, dependence, and the cultivation of autonomy in every citizen, to be developed over subsequent chapters.

I expect some readers will be growing increasingly impatient with my apparent acceptance and even advocacy of authority and dependence, and my remarks on the potentially problematic implications of certain ways of asserting human moral equality. Just what am I arguing for here? And why rehabilitate the oppressive term “master”? Let me address the second issue about mastery in order to prepare a clear response to the more general question of normative aims.

The word “master” has a bad odor today. For example, it has become dubious or even unacceptable to continue using “master” to name the leader of a residential college (i.e., a dormitory) at Harvard and Yale, a twentiethcentury American title that mimicked older British conventions regarding heads of colleges at Oxford and Cambridge.5 The moral horror motivating these changes is slavery, with its dreadful aftereffects continuing in American civic life, and critics of the word hear echoes of the title of slave “master” that attached to owners of enslaved people. Slavery obviously is as much an abomination today as it has always been, whatever any particular community decides about how to name administrative offices.

The word “master,” though, has a very long history, which spans the two most relevant senses of authority addressed in this book, and also serves as the most natural way in English to refer to becoming excellent at some complex art or practice. It is thus precisely the word to use to raise the issues this study engages. Descending from the Latin magister via the French maistre, “master” has a deep and complex history, which ties together two different but related ideas of authority: first, someone who controls something or some group of people through wielding effective power over it; and second, someone who is a teacher, genuinely qualified to teach others. There

are many variations, including numerous traditional titles for various offices, and the name for the most common graduate degree. The most crucial sense of the word, for this project, is the idea of mastering an art or craft through long study and practice.6 It is most crucial because mastery in this sense turns out to be the central paradigm for Confucian conceptions of virtue and, thus, as we shall see, practical authority. The early Rú also systematically relate their ideas about virtuous mastery to actual political authority, held by those in powerful governmental offices. Thus the double meaning captures their range of interest in and analysis of authority, and appropriately signals the themes of this study.

My overarching goal in this book is to articulate what I think contemporary Westerners need to learn from early Confucians regarding authority, dependence, and the cultivation of autonomy. I am not trying to develop a form of “new Confucianism,” nor am I trying (ludicrously) to offer advice to East Asians about how they should reform their governments or even their cultures. I do view early Rú thinkers as equivalent in intellectual significance to classical Western figures like Aristotle and Augustine, and thus see them as worthy of engagement as potential sources of theoretical insight. This is all the more true because of contemporary Western ethicists’ and political theorists’ relative unfamiliarity with their ideas. In other words, I view them as wise but far from perfect interlocutors, worthy of great respect and attention, but do not see them as infallible authorities—because there are no infallible human authorities.

The early Rú do not share modern Western commitments to egalitarianism, but they have a much stronger sense of universal human moral and intellectual potential than thinkers like Plato and Aristotle (Munro 1969). They also articulate their ethical and political ideas in a more obviously generic and universal form, addressed to all human beings who must live together in communities, and indeed in large, bureaucratically run states. If modern thinkers such as Friedrich Nietzsche, Bernard Williams, Alasdair MacIntyre, and Martha Nussbaum can rehabilitate key themes from the ancient Greek and Roman philosophers in new forms, the early Chinese political and ethical theories this study engages represent a comparatively easy lift, despite the greater linguistic differences from English. (In chapter 2 I address more fully just how different from our own ideas early Chinese thought and culture should be seen to be.)

Broadly speaking, I hope this study will contribute to more widespread interest in what I consider powerful and attractive Confucian ideas. I aim to

help contemporary Westerners untie some of the intellectual knots regarding authority and especially obedience that have kept us from properly grasping the real failings in Enlightenment-inspired political and ethical theories, without sliding into unjustified reactionary authoritarianism, or defeatist Romantic yearning for a lost haven of meaningful, integrated community life. And at the most substantive level I aim to contribute to what has come to be called liberal or moderate “perfectionism,” in work by thinkers such as Vinit Haksar, Joseph Raz, Thomas Hurka, George Sher, and Steven Wall, recently augmented by Confucian contributions from Stephen Angle, Joseph Chan, and Sungmoon Kim. I also hope to contribute to contemporary feminist reflection on dependence and its relation to autonomy and hierarchy, building on work by Eva Feder Kittay, Martha Fineman, Jennifer Nedelsky, and Nancy Folbre, among many others.

1.2. “From Status to Contract”: Myths and Histories of Authority’s Decline

The history of modern Western religious and philosophical thought has often been told as a set of related stories organized around one central theme: “the flight from authority.” As Jeff Stout writes: “modern thought was born in a crisis of authority, took shape in flight from authority, and aspired from the start to autonomy from all traditional influence whatsoever” (1981, 3).7 The rough outlines of this intellectual history are quite familiar and can be told as the gradual triumph of empirical science over religious dogmatism; or, more subtly, as the fragmentation of intellectual authority into a number of disintegrated spheres or “disciplines,” separating out theology, philosophy, and the natural and human sciences.

The intellectual history relies on a related story about social and especially political changes that gradually secularized a number of realms that were previously governed, at least in theory, by religious authorities. In brief, these histories correlate dramatic changes in intellectual authorities with equally dramatic changes in political authorities. In Europe, Protestant reformers challenged the Roman Catholic Church hierarchy as corrupt, preferring instead to submit to the authority of the Bible. For a variety of reasons, the resulting conflicts between Protestants and Catholics were savage, aptly described as the “wars of religion.” Struggling to arrive at a way to attain public order and peace without relying on contested religious premises,

jurists such as Hugo Grotius updated the Christian tradition of theorizing about the “natural law,” and ended up inventing the beginnings of secular governance. Intense early modern disputes over who, if anyone, really had a right to rule gradually led to a search for a basis for political order outside of an alliance between religious leaders and supposedly noble kings. With the advent of the Enlightenment, democratic political revolutions gradually made increasingly real alternative forms of government, based at least nominally on “the consent of the governed.” At the same time, in a roughly parallel set of maneuvers, moral philosophers attempted to provide intellectual foundations for morality that would appeal to all rational beings, regardless of their religious loyalties—the most influential traditions of this sort are probably Kantianism and utilitarianism. These philosophies made human moral equality a cardinal premise of rational morality.8

This history is long and complex, and obviously beyond the scope of this chapter to address adequately. Moreover, it has been narrated quite ably by many others. The point of this section and the next is, instead, to suggest in general terms why modern Western debates about authority have been structured in what has become their characteristic way: as debates focused on who can legitimately demand compliance from others, backed up with the coercive power of the legal system, often linked to a duty obliging those others to obey the authority’s commands. Moreover, this authority to command obedience appears to threaten what many heirs to the Enlightenment regard as the paramount human characteristic, the very ground of our equal human dignity, that is, our rational autonomy. To outline how and why these developments took this form, I will briefly discuss two landmarks of intellectual history: a highly influential nineteenth-century account of what makes modernity modern, provided by Henry Maine, and Isaiah Berlin’s almost equally influential account of “liberty” that reflects twentieth-century thinking about the dangers of potentially oppressive government action, even when pursued in the best interests of citizens.

Let us begin with Henry Maine’s (1866) Ancient Law: Its Connection with the Early History of Society, and Its Relation to Modern Ideas. 9 Maine’s book established the historical study of law as a worthwhile intellectual endeavor, and it was a classic version of world-spanning, evolutionarily inclined, nineteenth-century European comparative argument. Maine’s central thesis was that human social history could be summarized as the move “from status to contract,” with the invention of contractual relations and their attendant legal and institutional support system being a distinctively modern

development. In contrast, “ancient law,” which mostly enumerated custom from time immemorial, reflected a society based on the status of various persons, such as wives, children, and slaves, within patriarchal households. Only the father could enter into legal contracts; all others were unfree dependents without the legal and property rights of the father. Maine’s key motif is gradual emancipation: over time more and more social relations are conceived on the model of a contract entered into freely by equal citizens under the rule of law, and fewer relationships are defined by the status, with associated duties and prerogatives, of the parties involved.

In this account, autonomous agents who can own property, control their own activity, and freely enter into binding contracts regarding, for example, their own labor, become the modern norm. Other relations, such as slavery or the dependence of wives on husbands, are marked as archaic. Maine thereby demarcates the modern liberal realm of the public and contrasts it with a private realm where ancient customs linger on, perhaps out of biological necessity. This mapping of social life continues to capture central features of the modern Western cultural imagination. A crucial consequence of these developments is a sense that hierarchical relations are somehow strange and questionable because they deviate from the model of autonomously chosen agreements between equals.10 Such relations must apparently be based on archaic, “traditional” conceptions of status that we should be glad to have lost.

The primary remaining place for authority, in Maine’s scheme, is for the orderly enforcement of contracts. (His was a history of law.) We thus need a legal system, and political authorities empowered to execute and defend that system, which itself ought to be premised on the equal autonomy of citizens. The gradual expansion over time of who might count as a citizen only deepened the hold of this basic conception of rightly ordered social life. But what is the right scope for laws, and thus for governmental action generally? Should it stick to enforcing contracts, and warding off crimes, or should it take various actions to support the autonomy of citizens? To address common views of these questions, let us turn now to Isaiah Berlin.

Isaiah Berlin’s tremendously influential 1958 essay, “Two Concepts of Liberty,” is a history of Western political theory, not law per se.11 But it crisply captures and explains the enduring appeal of giving what he calls “negative” liberty priority over a different conception, “positive” liberty. Regardless of its erudition and sensitive, humane spirit, it is very much a document of the Cold War, and seeks among other things to explain how Western rationalist philosophy, including forms dedicated to the freedom of the individual, has in

practice ended up justifying and inspiring illiberal revolutionary movements and even totalitarian regimes. It takes as its central topic the “greatest” of the “dominant issues of our world”: “the open war that is being fought between two systems of ideas which return different and conflicting answers to what has long been the central question of politics—the question of obedience and coercion” (Berlin 1997, 193). Berlin aims to provide an explanation of two contending political visions, leading to two conflicting accounts of proper political authority, conceived as the power to demand obedience and enforce compliance through coercive state power.

Amid the profusion of different doctrines of freedom in Western thought, Berlin discerns two primary types, “negative” and “positive.” Negative liberty is freedom from interference from others, including governmental representatives, in the pursuit of one’s goals (194–95, 198–99; see also 202 n. 1 for caveats and details). Negative freedoms are rights to be left alone, of the sort guaranteed in the American Bill of Rights. Positive liberty, by contrast, is freedom to live as “one’s own master,” “conscious of myself as a thinking, willing, active being, bearing responsibility for my choices and able to explain them by reference to my own ideas and purposes” (203). Positive freedom, then, is the capacity or power to live according to one’s own judgment, as a rational agent choosing what to do, within the limits of what law permits and what is actually possible in the natural world.

While these may not seem intrinsically distant from each other, Berlin charts their divergence over time, particularly when paired with strong rationalist premises about the rational agency that positive freedom instantiates. Positive freedom is a way of talking about self-realization through developing one’s own rational agency—i.e., “self mastery.” Berlin suggests that the seemingly harmless metaphor of self-mastery, in the sense of self-control or self-command, implies a contrast between a higher self, often identified with reason, and a lower self that must be controlled or overcome, often identified with irrational impulse, desire, or passion. The “true” or “higher” self may also “be conceived as something wider than the individual . . . as a social ‘whole’ of which the individual is an element or aspect: a tribe, a race, a Church, a State” (204). When such a move is made, an individual’s own will and choices can appear to be ignorant or misguided when in conflict with the “collective, or ‘organic’ ” will of the larger social entity. Coercion of the backward and recalcitrant starts to seem quite reasonable on these premises, since it is done “for their own sake, in their, not my, interest” (204). And sometimes authorities can even claim that those they are coercing have unconsciously

chosen what their rulers say is best, despite their expressed dissent. (We might here imagine some Soviet apparatchik referring to the “unconscious” wishes of recalcitrant peasants to join collective farms, when in fact they have to be dragged to them by force.) Berlin comments: “This monstrous impersonation, which consists in equating what X would choose if he were something he is not, or at least not yet, with what X actually seeks and chooses, is at the heart of all political theories of self-realisation” (205). This is an extraordinarily strong denunciation of political theories that aim to cultivate citizens’ positive freedom, rather than simply protect their negative freedom from encroachment. Do all such theories really center on lying about people’s actual choices in comparison to their ideal or best choices? The answer is clearly no, but to see why Berlin feels compelled to render this verdict on the Western tradition of political theory, we should examine how he sees political theory linked to theories of personal formation.

Berlin examines in some detail the way philosophical theories of selfrealization in the West have borne fruit over time. One strand he charts is the Stoic “retreat to the inner citadel,” which consists in contracting the frontiers of one’s personal “kingdom” in order to ward off vulnerability to misfortune. Berlin thinks the characteristic modern form of this view is Kant’s moral philosophy, in which the noumenal rational self struggles to assert its (rational, autonomous) control of the self, against the “heteronomy” of “slavery to the passions” (206–12, 210). This line of thought, Berlin argues, shows the inadequacy of defining negative liberty, as he suggests J. S. Mill does, as “the ability to do what one wishes”—if one’s wishes can be contracted or perhaps extinguished, “I am made free” (211). “Ascetic self-denial may be a source of integrity or serenity and spiritual strength, but it is difficult to see how it can be called an enlargement of liberty,” Berlin writes (211).

According to Berlin, European theories of rational self-realization actually go much further than this: advocates of rational enlightenment including Spinoza, Herder, Hegel, and Marx insist that “to understand the world is to be freed” (214). Reason liberates us from error and frustration. Once we see clearly, we will affirm what reason dictates and only that. Liberation by reason, Berlin suggests, is “at the heart of many of the nationalist, communist, authoritarian, and totalitarian creeds of our day” (216). Why is this? Because a number of thinkers, including in addition Rousseau, Kant, and Fichte, transform the originally individualist doctrine of rational self-direction into a social doctrine, and seek to understand how a rational life is possible for