NoteonTranscriptionsand CatalogueNumbers

Intheinterestsofbrevity,Ihaveprovidedonly STC numbersforallbooksprinted inEnglandorforanEnglishreadership.BooksprintedinEuropeforeitheran internationalmarketoranothercountryarereferredtobytheir ISTC numberif printedbefore1501andbytheir USTC numberifprintedafterwards,thoughthe latter’scoverageisnotyetperfect.Ihaveusedthedatesfromtherelevant catalogue,exceptwherenoted.Wherecopy-specificfeaturesarediscussed Iprovideidentifyinginformationforthatcopyinthefootnotes.

Inmyowntranscriptionsforeaseofreadingandtoincreaseaccessibility, abbreviationshavebeenexpandedanditalicized,romannumeralssilently replacedbyeitherwordsorArabicnumeralsasappropriateandthornssilently replacedby th.Virguleshavebeenchangedtocommas,butpunctuationhas otherwisebeenleftunchangedunlessitinterfereswithintelligibility.Titlesof editionshavebeenmodernized.Pagesareusuallyreferredtobysignature,except wheretheoriginalhasfolionumbers.Veryoccasionally,whereneithersignatures norfolionumbershavebeensuppliedbytheprinter,Iusetheunmarkedfolio numberorotherlocator,suchaschaptertitle.

Introduction

[Publishers’]salesandmarketingactivitiesareconcernednotsimply tobringaproducttothemarketplaceandletretailersandconsumers knowthatitisavailable;theyseek,morefundamentally,to builda market forthebook.Topublishinthesenseofmakingabook availabletothepublic iseasy ...Buttopublishitinthesenseof makingabook knowntothepublic,visibletothem,andattractinga sufficientquantumoftheirattentiontoencouragethemtobuythe bookandperhapseventoreadit,isextremelydifficult ...Good publishers...aremarket-makers.¹

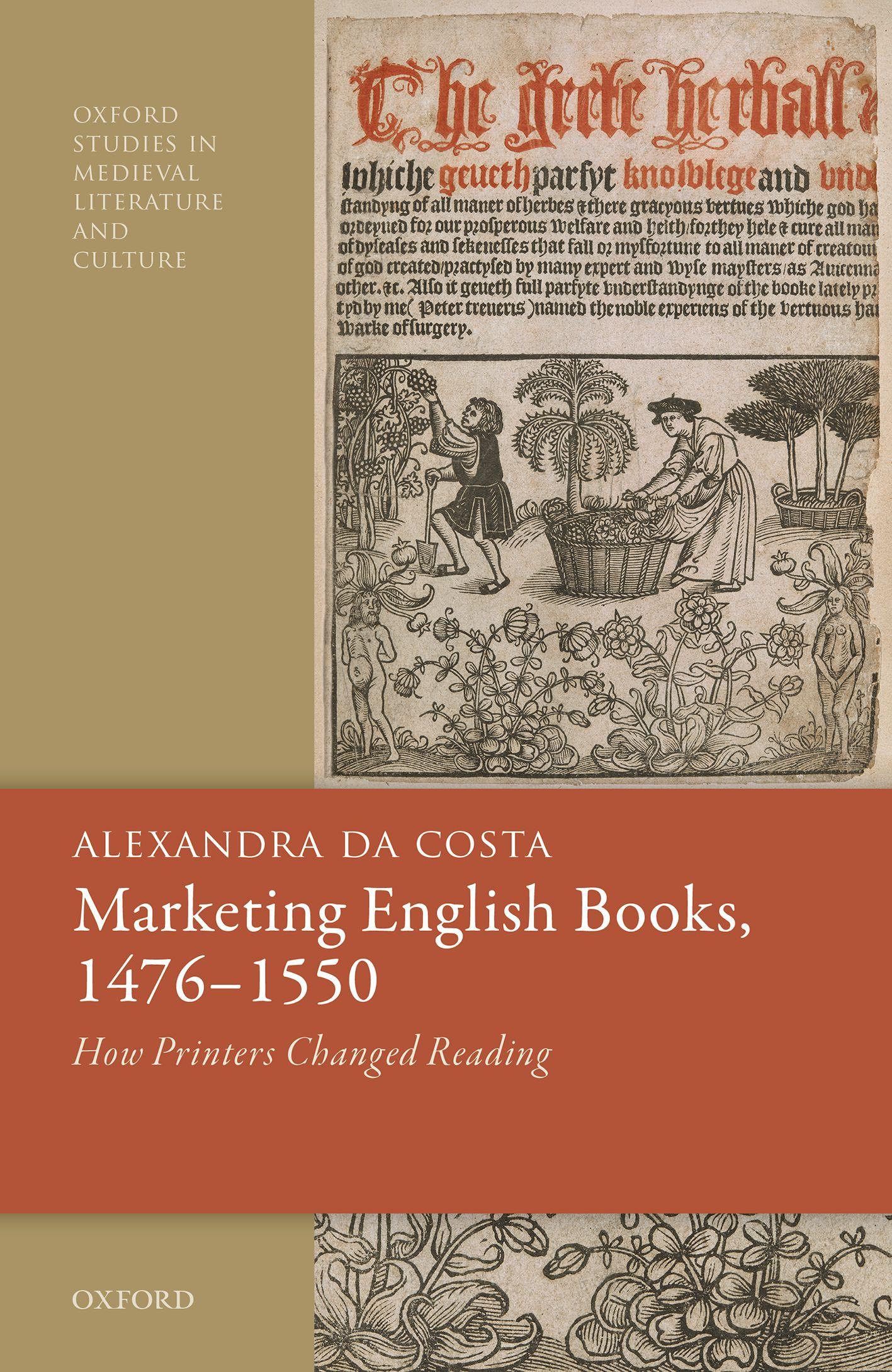

Thisobservationisastrueofprintersinthelate fifteenthandearlysixteenth centuriesasitisforpublishersinthetwenty-firstcentury.Untiltheadventof print,thesaleofbookshadbeenprimarilya ‘bespoketrade’,butprintersfaceda newsaleschallenge:howtosellhundredsofidenticalbookstoindividuals.²This droveprinterstothinkcarefullyabout(whatwenowcall)marketingandpotential demand,foreveniftheysoldthroughamiddleman asmostdid thatwholesaler,bookseller,orchapmanneededtobeconvincedthebookswouldattract customers.³ MarketingEnglishBooks setsout,therefore,toshow how marketsfor particularkindsofworkwerecultivatedbyprintersbetween1476and1550by focusingonthreebroad(butnotwhollydiscrete)categories:religiousreading,

¹JohnThompson, MerchantsofCulture:ThePublishingBusinessintheTwenty-FirstCentury (2010),p.21.

²GrahamPollard, ‘TheEnglishMarketforPrintedBooks:TheSandarsLectures,1959’,in PublishingHistory:TheSocial,EconomicandLiteraryHistoryofBook,NewspaperandMagazine Publishing 4(1978):pp.7–48,p.10.Onspeculativeproductionofmanuscripts,seeLinneMooney, ‘VernacularLiteraryManuscriptsandtheirScribes’,in TheProductionofBooksinEngland1350–1500, editedbyAlexandraGillespieandDanielWakelin(2011),pp.192–211;J.J.G.Alexander, ‘Foreign IlluminatorsandIlluminatedManuscripts’,in CHBBIII,pp.47–64,p.53;A.I.Doyle, ‘TheEnglish ProvincialBookTradebeforePrinting’,in SixCenturiesoftheProvincialBookTradeinBritain,edited byPeterIsaac(1990),pp.13–29,p.17;andCarolM.Meale, ‘Patrons,BuyersandOwners:Book ProductionandSocialStatus’,in BookProductionandPublishinginBritain1375–1475,editedby JeremyGriffithsandDerekPearsall(1989),pp.201–38,p.218.

³ThisbookisinspiredbyA.S.G.EdwardsandCarolM.Meale’sseminalarticle, ‘TheMarketingof PrintedBooksinLateMedievalEngland’,whichbegantoexplorehowearlyprintersapproached ‘what wewouldnowterm “marketing”:theidentificationofwaysinwhichprintedbookscouldannex existingmarketsorestablishnewones’ . TheLibrary,s6–15(1993):pp.95–124,p.95,doi.org/10.1093/ library/s6-15.2.95.SeealsoTamaraAtkinandA.S.G.Edwards, ‘Printers,PublishersandPromotersto 1558’,in ACompaniontotheEarlyPrintedBookinBritain1476–1558,editedbyVincentGillespieand SusanPowell(2012),pp.27–44.

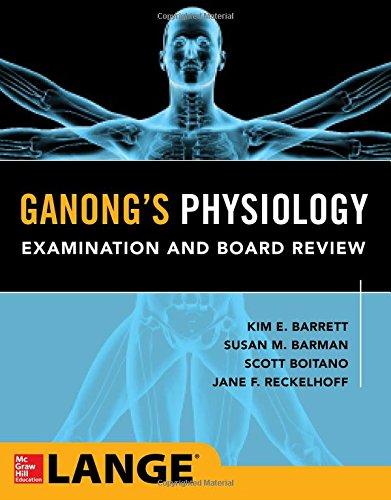

MarketingEnglishBooks,1476–1550:HowPrintersChangedReading.AlexandradaCosta,OxfordUniversityPress(2020). ©AlexandradaCosta. DOI:10.1093/oso/9780198847588.001.0001

secularreading,andpracticalreading.Withinthosecategories,thechaptersfocus indetailonthedevelopmentoftypesofbookthateitheremergedforthe firsttime duringthisperiod(evangelicalbooks,newspamphlets)orunderwentconsiderablechangesinpresentation(devotionaltexts,romances,travelguides,household works).⁴ Thebookarguesthatwhileprintandmanuscriptcontinuedalongside eachother,developmentsinthemarketingoftheseprintedtextsbegantochange whatreadersreadandtheplaceofreadingintheirlivesonalargerscaleandata fasterpacethanhadoccurredbefore,shapingtheirexpectations,tastes,andeven theirpracticesandbeliefs. ⁵

Theexactpercentageofthepopulationthatcouldreadinthisperiodisamatter ofdebate,but,accordingtoJ.B.Trapp, ‘aguessthat,inthesecondquarterofthe sixteenthcentury,halftheadultpopulationofthecountrycould,insomesenseof theword,readEnglishmightnotbewideofthemark’ . ⁶ Whatthatmightmeanin practicevariedenormously.Thekindofliteracythatareaderpossessedtendedto correlatewiththeirsocialrankandoccupation.MalcolmParkesdistinguishes betweentheliteracy ‘oftheprofessionalreader,whichistheliteracyofthescholar ortheprofessionalmanofletters;thatofthecultivatedreader,whichisthe literacyofrecreation;andthatofthepragmaticreader,whichistheliteracyof onewhohastoreadorwriteinthecourseoftransactinganykindofbusiness’ . ⁷ Literacywasnotevenlydistributed urbancommunitiestendedtohaveagreater concentrationofreadersandthereweremorereadersamongthenobility,gentry, andmerchantclassthaninlowerranksofsociety buteventhosewholacked literacymightbenefitfromitthroughlisteningtoothersreadorrecounttheir reading.⁸ Thisbookisconcernedwiththegrowingnumbersofsecularreaders withcultivatedorpragmaticliteracywhoboughtbookseitherdirectlyfrom printersorthroughbooksellersandchapmen.Thesewerethekindofreader whowereunlikelytohaveLatinandthereforemostlikelytoacquirebooks fromEnglishprinters,sincethelatterhadsetoutto fillagapinthemarketby

⁴ Foradiscussionofhowprintersmarketedmoreliteraryworks,seeAlexandraGillespie’ s Print CultureandtheMedievalAuthor:Chaucer,Lydgate,andtheirBooks1473–1557 (2006),whichprovides arichanalysisofhowprinters ‘madeEnglishliterarytextsinto “goods”’ andusedtheideaoftheauthor to ‘provideawealthofreasons’ forsomeonetobuyatext(p.228).

⁵ JuliaBoffey’ s ManuscriptandPrintinLondonc.1475–1530 (2012)explorestherelationship betweenmanuscriptandprint,andhowitaffectedthedecisionsmadebywritersandreaders.

⁶ J.B.Trapp, ‘Literacy,BooksandReaders’,in CHBBIII,pp.31–43,pp.39–40.SeealsoM.B.Parkes, Scribes,ScriptsandReaders:StudiesintheCommunication,PresentationandDisseminationofMedieval Texts (1991),p.296.J.W.Adamsonoffersasimilarlygenerousestimatein ‘TheExtentofLiteracyin EnglandintheFifteenthandSixteenthCenturies:NotesandConjectures’ , TheLibrary,s4.10(1929): pp.163–93,p.193,doi.org/10.1093/library/s4-X.2.163.

⁷ Parkes, Scribes,ScriptsandReaders,p.275.

⁸ CynthiaZollinger, ‘“Thebooke,thelefe,yeaandtheverysentence”:Sixteenth-CenturyLiteracyin TextandContext’,in JohnFoxeandhisWorld,editedbyChristopherHighleyandJohnN.King(2002), pp.102–16,p.103.Onhow ‘literacyinteractedwithotherformsofcommunication’ seeBobScribner, ‘Heterodoxy,LiteracyandPrintintheEarlyGermanReformation’ in HeresyandLiteracy1000–1530, editedbyPeterBillerandAnneHudson(1994),pp.255–78,p.259.

supplyingthesereaderswithvernacularbooks,whereasthe ‘Latin(i.e.imported) tradewasaimedprimarilyattheuniversities,thereligiousandtheclergy’ . ⁹

Thisisnot,however,abookconcernedjustwithprintinginEnglishandin England.AlthoughthemajorityofbooksprintedinEnglandwereinEnglishand intendedfornativereaders,thebooktradeasawholehadlongbeenaninternationaltradedominatedbyLatin.¹⁰ ForeignstationershadshopsinLondonor sentbooksonrequest,andproducersabroadcreatedbooks,bothmanuscriptand print,specificallyforEnglishmarkets.¹¹Someofthemostperipateticartisanswere scribesandilluminators.¹²PrintedbookswereavailableinLondonmorethana decadebeforeCaxtonestablishedhispressanditwascommonforprintedbooks tobeimported.¹³AnneSuttonandLiviaVisser-Fuchspositthat ‘by1480...any enthusiasticscholarcouldgetanyprintedtextfromanywhere;itjusttooktime andpersistence.’¹⁴ MargaretLaneFord’sanalysisof4,300extantprintedbooks withclearmarksofEnglishandScottishownershipsuggeststhatuntilthe1550s, German-speakingcountriesproduced33percent,Italy25percent,France24per cent,andtheNetherlands8percent.Nativeprinterswereresponsibleforonly10 percent.¹⁵‘Throughtheendofthe fifteenthcentury,andwellbeyond,aprinted bookpurchasedinBritainwouldjustaseasilybearacontinentalimprintasa domesticone.’¹⁶ Indeed,whenFernandoColónvisitedLondonin1522hepurchasedeightybookstosendbacktoSeville,ofwhichonlyeightwereprintedin England.¹⁷ Andofcourse,when ‘Englishprinters’ arereferredtointhisbook, whatisreallymeantis ‘printersinEngland’ formanyhadbeenbornonthe Continent.Amongthe fifteenth-centuryprintersinLondon,Caxtonwastheonly oneborninEngland.¹⁸ Sowhilethisbookfocusesontheeffortsofprintersin Englandtomarketwhattheyprinted,thoseeffortsareplacedwithinawider Europeancontext.JustasEnglishmanuscriptsweremouldedby ‘foreign

⁹ MargaretLaneFord, ‘PrivateOwnershipofPrintedBooks’,in CHBBIII,pp.205–28,p.227.

¹

⁰ DavidRundle, ‘EnglishBooksandtheContinent’,in TheProductionofBooksinEngland 1350–1500,editedbyAlexandraGillespieandDanielWakelin(2011),pp.276–91.

¹¹A.S.G.Edwards, ‘ContinentalInfluencesonLondonPrintingandReadingintheFifteenthand EarlySixteenthCenturies’,in LondonandEuropeintheLaterMiddleAges,editedbyJuliaBoffeyand PamelaKing(1995),pp.229–56,p.238.

¹²M.A.Michael, ‘UrbanProductionofManuscriptBooksandtheRoleoftheUniversityTowns’,in CHBBII,pp.168–94,p.194.

¹³JuliaBoffey, ManuscriptandPrint,pp.125,128.Caxtonbothimportedandexportedbooks.Paul Needham, ‘TheCustomsRollsasDocumentsforPrinted-BookTradeinEngland’,in CHBBIII, pp.148–63,pp.154–5.

¹

⁴ AnneF.SuttonandLiviaVisser-Fuchs, ‘ChoosingaBookinLateFifteenth-CenturyEnglandand Burgundy’,in EnglandandtheLowCountriesintheLateMiddleAges,editedbyCarolineBarronand NigelSaul(1995),pp.61–98,p.64.

¹

⁵ MargaretLaneFord, ‘ImportationofPrintedBooksintoEnglandandScotland’,in CHBBIII, pp.179–201,p.183.

¹

¹

⁶ Needham, ‘TheCustomsRolls’,pp.148–9.

⁷ DennisRhodes, ‘DonFernandoColónandHisLondonBookPurchases,June1522’ , ThePapersof theBibliographicalSocietyofAmerica 52(1958):pp.231–48,p.233,doi:10.1086/pbsa.52.4.24299644.

¹

⁸ Edwards, ‘ContinentalInfluences ’,p.238.

influences inscript,inillumination,inmaterials,instructure’,Englishprinters weredemonstrablyinfluencedbythewaystheircontinentalcounterpartspresentedbooks,especiallythosethatwentthroughmultipleeditions.¹⁹

‘Lossesandcostsanddead-ends’ alsoinfluencedprinters’ decisions.²⁰ William Kuskinarguesthatprintersneeded ‘tostrategizenotjusttheirnextproject buttheoverallmarketfortheirbooks’ iftheyweretoreaptherewardsofthe capitalinvestmentintheirpresses.²¹However,Kuskin ’sapproachcanmake printingstrategyseemateleologicalprocessof ‘appropriationandconsolidation’ , ignoringJoadRaymond’swarningthat ‘thefrequencyofprinterandbookseller bankruptcies...suggeststhat[their]knowledgeofthemarketwasoftenimperfect’.²²Consequently,attentionisgivenheretowhatdidnotsellandthepossible explanationsforthat,aswellashowprintersrespondedtothosefailures,either theirownorthoseoftheircompetitors,domesticandforeign.Thefriabilityof earlyprintandlowsurvivalratesmakeithardtoknowforcertainwhatsoldwell asmanytextsandeditionshaveundoubtedlydisappearedwithouttrace,potentiallydistortingevidenceofpopularity.Conversely,TamaraAtkinarguesthat ‘the issueofanewedition[byadifferentprinter]didnotalwaysindicatethatthelast hadbeenasell-out’,onlythatthenewprinterhadconfidence ‘thatpotential buyersexistedinsufficientnumberstojustifytherisk’,resultingintheparadoxical situationwhere ‘aworkcouldbothruntonumerouseditions[bydifferent printers]andexistinalargenumberofremaindercopies.’²³Nevertheless,ithas seemedsafertoargueinthisbookonthebasisofwhathassurvivedratherthan hypotheticallosteditions,equatingthesurvivalofmultipleeditionsandthe publicationoffurthersimilarworksassignsofabuoyantmarket atthetime whenprintingwasundertakenandsingleeditions,editionsseparatedbyseveral decades,andalackofsuccessivesimilarworksasevidenceoflimitedorintermittentinterest.

Whileprinterswereinevitablyconcernedwithhowmanycopiesofatextthey couldsell,thisisunlikelytohavebeentheironlyinterest,asKathleenTonryhas

¹⁹ DavidRundle, ‘EnglishBooksandtheContinent’,p.291.Forwidercontext,seeDianeBooton, Manuscripts,MarketandtheTransitiontoPrintinLateMedievalBrittany (2010);EmmaCayleyand SusanPowell,eds, ManuscriptsandPrintedBooksinEurope1350–1550:Packaging,Presentationand Consumption (2013),andShantiGraheli,ed., BuyingandSelling:TheBusinessofBooksinEarly ModernEurope (2019).

²

⁰ JamesRaven, ‘SellingBooksacrossEurope, c.1450–1800:AnOverview’ , PublishingHistory 34 (1993):pp.5–19,p.5.

²¹WilliamKuskin, SymbolicCaxton:LiteraryCultureandPrintCapitalism (2008),p.52.

²²Kuskin, SymbolicCaxton,p.16.JoadRaymond, ‘Matter,SociabilityandSpace:SomeWaysof LookingattheHistoryofBooks’,in BooksinMotioninEarlyModernEurope:BeyondProduction, CirculationandConsumption,editedbyDanielBellingradt,PaulNelles,andJeroenSalman(2017), pp.289–95,p.291.

²³TamaraAtkin, ‘ReadingLate-MedievalPietyinEarlyModernEngland’,in MedievalandEarly ModernReligiousCultures:EssaysHonouringVincentGillespieonhisSixty-FifthBirthday,editedby LauraAsheandRalphHanna(2019),pp.209–41,p.210.

persuasivelyclaimed.Complicatingourunderstandingofprinters’ motivations anddifferentiatingherworkfrompreviousapproaches,shearguesthat

Modernscholarlyinterestinearlyprinthastendedtoreinscribeaconceptual breakbetweenprintandmanuscriptbyassumingthatprintershadquitelimited intellectualinvestmentsinthebookstheypublished.The fieldhaslargelyfocused onthecommercialandtechnologicalaspectsofearlyprint...Missingfromtheir discussionsarethewaysthatprintingwas(andis)alsoanactoftextualcreation, ofengaged,deliberate,intentional making,aswellasinterestinprintersasagents ofthatmaking.²⁴

Ratherthanfocusingsimplyonmotivesofprofitandloss,Tonryexploreshow printers’ ethicalandpoliticalcommitmentsinfluencedthemakingofbooks, framingherdiscussionintermsofagency.Shedefinesagency following KatherineO’BrienO’Keefe as ‘thecapacityforresponsibleindividualaction’ andasnotbeingopposedtoculturalstructure,butenabledbyit: ‘toexercise agencyrequiresactorstohaveknowledgeoftheculturalformswithinwhichthey areenmeshedandsomeabilitytoaffectthem.’²⁵ Forexample,shearguesthat Caxton’sprefacetoa BookofGoodManners preparesthereadertoseethetextas aninstantiationof ‘amercantileethosemphasizingthevaluesofself-regulation, autonomy,andanorientationtowardthecommonprofit’.²⁶

Here,Iseethekindof ‘intentionalmaking’ Tonrydiscussesasinseparablefrom, ratherthanantitheticalto,the ‘commercial...aspectsofearlyprint’.Printers expressedtheiragencyinthemarketingofbooksconstantly.Thatis,theydemonstratedtheirknowledgeoftheculturalformsinwhichtheyparticipated throughtheirstrategicdecisionsabouthowtomarketatext.Thosecultural formsweremultiple:bookculture,withitsdifferentgenres,traditionsofpresentationandreaderlyexpectations;mercantileculture,withitsexigencyof(ideally fair)profitandconcomitantresponsibilityforthefamily,workersandfellowguild membersinvolvedinthetrade;politicalculture,withitsrefusaltobroketoo criticalavoice;religiousculture,withitsdemandfororthodoxconformityand limitationsonacceptableknowledge;andsoforth.Printershadtonegotiateallof thisineverypublicationtheymade,stayingalerttotheenmeshedandshifting contextsinwhichitwouldbereceived.AlexandraHalaszdrawsattentiontothis whenshechallengesMarx’sdistinctionbetweenuse-valueandexchange-value andthe ‘primacyofproductivelaborindetermingvalue’ inthecontextof pamphletproduction.Shearguesinsteadthat

²⁴ KathleenTonry, AgencyandIntentioninEnglishPrint,1476–1526 (2016),pp.11–12.

²⁵ Tonry, AgencyandIntention,p.13,quotingO’BrienO’Keefe, StealingObedience:Narrativesof AgencyandIdentityinLaterAnglo-SaxonEngland (2012),pp.9,13.

²⁶ Tonry, AgencyandIntention,p.107.

...inorderfordiscoursetoacquireanexchangevalue,activeclaimshavetobe madeforitsuse/usefulnessasacommodity...Obviously,nosingleorselfevidentclaimofusefulnesscanserve;rather,suchclaimsmustbeimprovised repeatedlyinordertosecurepurchase,inordertomaketheexchangetransaction seemsensibleorbeneficial,inordertomakelisteners/readersintoconsumers.²⁷

Printersexpressedtheiragencyinthewaysinwhichtheyadopted,reinforced, altered,andadaptedthepresentationoftextstosecuresales.Indecidinghowto appealtopotentialcustomers,printershadtoknowwhentoutilizetradition drawingfromemergingandlong-standingconventionsofhowtopresenta work andwhentobeinnovative.Themarketingofaworkinthisperiod was toborrowaphrasefromaverydifferentsphere—‘apracticeofimprovisationwithinasceneofconstraint’.²⁸ However,itwasnotalwaysacoherent improvisation.RogerPooleyhasillustratedhowthepresentersofRenaissance textsused ‘apparentlycontradictorygestures’ toattractdifferentkindsofreaders. Thesamecanbesaidofearliermarketingattemptsandfocusingontheirapparent tensionscanrevealthediversityofreaderstowhichprinterssoughttoappealand themultiplecontextstheyhadtonegotiate.Themarketingofearlyprintedbooks hadthepotentialtomakeasignificantculturalimpactandinvolvedmore complexjudgementsthanjustwhatpresentationaltoolstouse.

The firststepincreatingamarketinthisperiodwassimplytotaketheriskof makingatextavailabletothepublic,withoutwhichdemandcouldneitherbe testednorencouraged.Whenprintersventuredtodothistheydiditinasan informedamanneraspossible,judgingthepotentialmarketbytakinginto accountsuchthingsasmanuscriptpopularityandthesuccessofcontinental editions,eitherofthesameworkinadifferentlanguageorofasimilargenre. Theysoondiscoverediftheyhadmadeamisjudgementthroughtheharshlessons ofpoorsales,butalsopaidattentiontocustomerfeedback,asananecdoteby ThomasPaynellreveals.InhisprefacetohistranslationofUlrichvonHutten’ s De morbogallico (STC 14024,1533),Paynellrecords:

Notlongeagoo,afterIhadtranslatedintoourenglysshetongethebokecalled RegimensanitatisSalerni [STC 21596,1528],IhapnedbeingatLondontotalke withtheprinter[ThomasBerthelet],andtoenquireofhym,whathethought, andhowhelykedthesameboke:andheanswered,thatinhismynde:itwasa bokemochenecessarye,andveryprofitableforthemthattokegoodhedetothe holsometeachynges,andwarelyfolowedthesame.Andthismochefartherhe addedtherto,thatsofarfortheaseuerhecoudehere,itisofeuerymanverywell

²⁷ AlexandraHalasz, TheMarketplaceofPrint:PamphletsandthePublicSphereinEarlyModern England (1997),p.29.

²

⁸ JudithButler, UndoingGender (2004),p.1.

acceptedandallowed.AndIsayd,Ipraygoditmaydogood,andthatisallthat Idesyre.Andthusintalkyngeofonebokeandofanother,hecamefortheand sayde:thatifIwoldetakesomochepeyneastotranslateintoInglysshetheboke thatisintitled Demedicinaguaiaci,etmorbogallico wrytenbythatgreatclerkeof AlmayneVlrichHuttenknyght,Ishulde,saydhe,doaveryegooddede...For almosteintoeueryeparteofthisrealme,thismoostefouleandpeynfulldiseaseis crepte,andmanysooreinfectedtherwith.Whanhehadsaydthushisfantasye, andthatIhaddebethoughtemeandwelladuysedhiswordes,Ianswered... (sig.[p]1r–v,italicsindicateRomantype)²⁹

Paynellobviouslyrelatedthisencountertosellmorecopiesofthe Regimen sanitatisSalerni,puttingintoBerthelet ’smouthwordssimilartothoseonthe title-pageofthe firsteditionofthe Regimen andofferingevidenceofitbeingwell regardedtofurtherencourageinterest.³⁰ But,indoingso,heportrayedtheprinter asproactivelylisteningforcommentsaboutapasteditionhehadprinted,paying attentiontothefortunes ‘ofonebokeandofanother’—includingpresumablythe successofHutten ’sworkthathadbythattimebeenprintedinParis,Bologna,and Mainz andenteringintoa ‘fantasye’ abouthowtotakecommercialadvantageof thespreadofsyphilisinEngland.Whilewritersandtranslatorsmightbringatext toaprinter,unlesstheywerealsowillingtotakeonallthecommercialrisksof printingit andthisseemstohaverarelybeenthecase theprinterhadtojudge itsmarketviabilityandthatrequiredthekindofalertnessthatPaynelldepicts.The precisereasonsbehindadecisiontopublishcanrarelybepinneddown,butthis bookestablishessomeofthefactorsthatmayhavecontributedtotheprintingofa textandwhyaprintermighthavethoughtitlikelytosellwell.

Onceaprinterdecidedtopublishatext,thesecondstepwastoworkouthowto attracttheinterestofreadersor,inThompson’swords,howtomakeabook ‘knowntothepublic,visibletothem’.Tocreatemarketsfortheirbooks,early printershadtouse,whatGérardGenetteterms,the paratext. Paratexts arethe ‘productions,themselvesverbalornot,likeanauthor’sname,atitle,apreface, illustrations’ thatsurroundatext ‘inorderto present it,intheusualsenseofthis verb,butalsoinitsstrongestmeaning:to makeitpresent,toassureitspresencein theworld,its “reception” anditsconsumption.’³¹Therearetwotypesofparatext.³² Peritexts arethoseelementsofpresentationthatsurroundatext,likeatitle

²⁹ H.S.Bennettcitesthispassageandconcludesthat ‘encouragementsuchasthissetthetranslatorto work’ withoutofferingfurthercomment. EnglishBooksandReaders1475to1557:BeingaStudyinthe HistoryoftheBookTradefromCaxtontotheIncorporationoftheStationers’ Company (1969), pp.42–3.

³

⁰ Thetitle-pageofthe firsteditionofthe RegimensanitatisSalerni describesitasabook ‘ as profitable&asnedefulltobehadandreddeasanycanbetoobseruecorporallhelthe’ .

³¹GérardGenette,trans.MarieMaclean, ‘IntroductiontotheParatext’ , NewLiteraryHistory 22 (1991):pp.261–72,p.261,https://www.jstor.org/stable/469037.

³²Genette, ‘IntroductiontotheParatext’,pp.263–4forthedefinitionsofperitextsandepitexts.