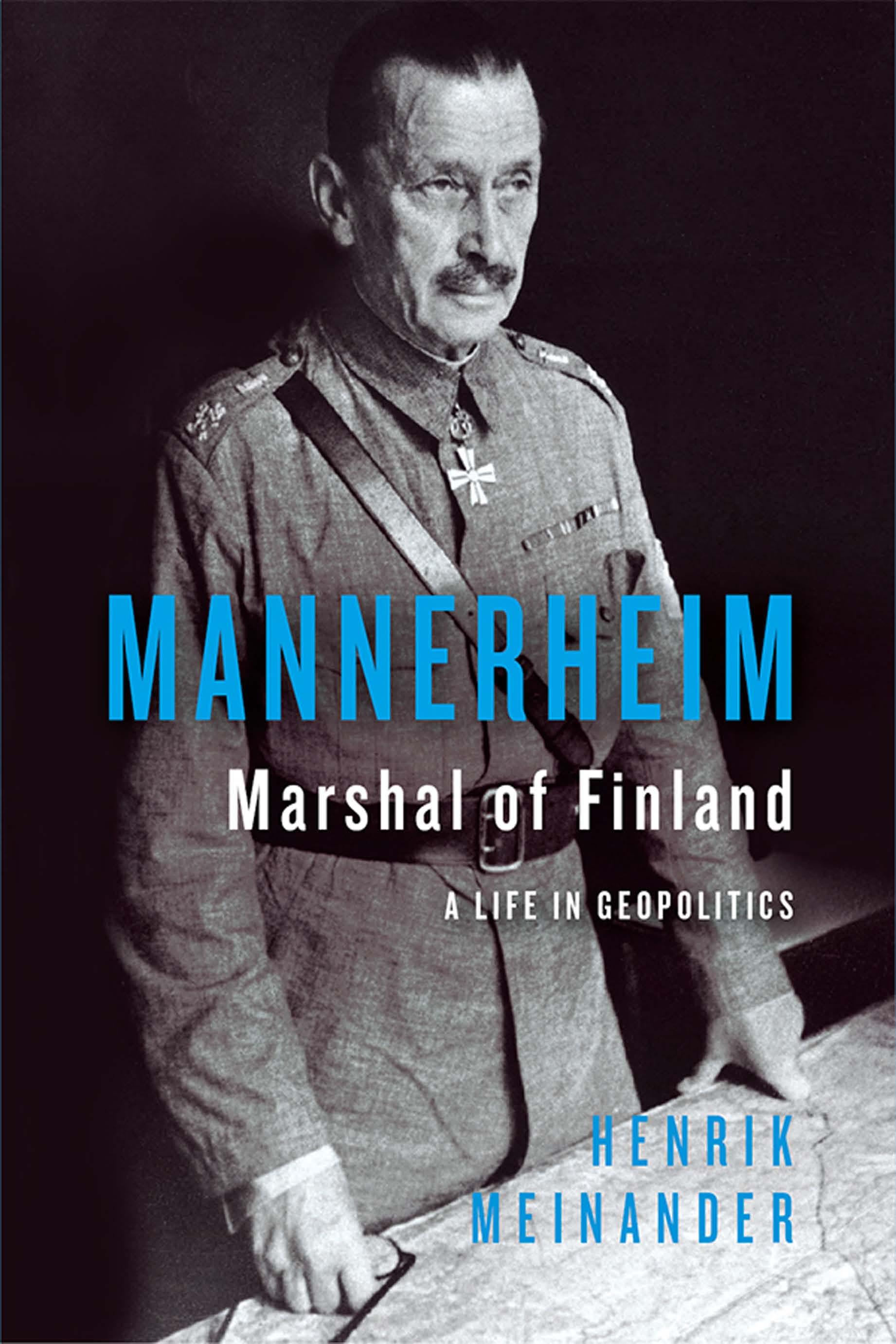

Mannerheim, Marshal of Finland

A Life in Geopolitics

HURST & COMPANY, LONDON

First published in the United Kingdom in 2023 by C. Hurst & Co. (Publishers) Ltd.,

New Wing, Somerset House, Strand, London, WC2R 1LA

© Henrik Meinander, 2023

All rights reserved.

Distributed in the United States, Canada and Latin America by Oxford University Press, 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

The right of Henrik Meinander to be identified as the author of this publication is asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988.

A Cataloguing-in-Publication data record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 9781787389373

This book is printed using paper from registered sustainable and managed sources. www.hurstpublishers.com

LIST OF MAPS

Fig. 1.6: The expanding railway network of the Russian Empire between 1890 and 1919. 26

Fig. 3.1: The route of Mannerheim’s 14,000-kilometre journey across Asia.

57

Fig. 4.1: The Baltic section of the Eastern Front between March 1917 and March 1918. 84

Fig. 7.4: The transformation of the political map of Northern Europe in 1940. 183

Fig. 8.5: The development of the Eastern Front between September 1943 and December 1944. 212

Fig. 9.3: Soviet-dominated post-war Europe. 234

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

Fig. 1.1: Louhisaari Manor, Mannerheim’s birthplace and childhood home. Drawing by Gunnar Berndtson. 2

Fig. 1.2: Brothers Count Carl and Baron Gustaf Mannerheim, 1884. Mannerheim Museum photo archives. 5

Fig. 1.3: Homework test in Hamina Cadet Corps. Illustration by Hugo Backmansson. From Backmansson, Hugo: Teckningar ur kadett-lifvet. Helsingfors, 1892. 11

Fig. 1.4: The 20-year-old civilian Mannerheim, between military schools in 1887. 18

Fig. 1.5: Mannerheim (right) and a young colleague at the Nicholas Cavalry School, 1888. Mannerheim Museum photo archives. 19

Fig. 1.6: see List of Maps

Fig. 2.1: Chevalier Guards’ officer Mannerheim in full dress uniform, 1892. Mannerheim Museum photo archives. 29

Fig. 2.2: Anastasia Mannerheim, née Arapova, in the mid-1890s. Mannerheim Museum photo archives. 34

Fig. 2.3: Nicholas II’s coronation in May 1896, with Mannerheim on the right. Finnish Heritage Agency HK10000:2368 (Creative Commons CC BY 4.0). 38

Fig. 2.4: The Russian troops’ chaotic retreat after the Battle of Liaoyang, 1904. German illustration from the period. From Gädke, Oberst: Japans Krieg und Sieg. Politisch-militärische Beschreibung des russisch-japanischen Krieges 1904–1905. Berlin, c. 1910. 49

Fig. 3.1: see List of Maps.

Fig. 3.2: Southern Xinjiang, August 1906: Mannerheim (right) visiting a local celebrity, the 96-year-old Alasjka Tsaritsan. Photo by Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim himself. 62

Fig. 3.3: Major-General Mannerheim in 1912, Commander of the Imperial Life Guards’ Uhlan Regiment in Warsaw and General in the Imperial Retinue. Mannerheim Museum photo archives. 67

Fig. 3.4: Mannerheim in conversation with Marquess Aleksander Wielopolski in Poland in the early 1910s. Otava photo archives. 71

Fig. 3.5: Mannerheim cross-country riding in Poland, 1914. Mannerheim Museum photo archives. 74

Fig. 3.6: Mannerheim inspects a bicycle battalion at the Transylvanian Front, turn of 1916–17. Mannerheim Museum photo archives. 78

Fig. 4.1: see List of Maps.

Fig. 4.2: The satirical newspaper Kerberos’s summary of Mannerheim’s and the Germans’ role in the Finnish Civil War. National Library of Finland. 92

Fig. 4.3: Mannerheim shaking hands with von der Goltz, German commander in Finland, at a victory parade on Senate Square, Helsinki, 16 May 1918. Finnish Heritage Agency HK198 60105:1.31d (Creative Commons CC BY 4.0). 98

Fig. 4.4: The Regent gives a speech to elementary grammar schoolteachers in Helsinki, spring 1919. Otava photo archives. 103

Fig. 5.1: Mannerheim (second from right) on the steps of his summer villa in Hanko with Dutch guests, 1925. Mannerheim Museum photo archives. 118

Fig. 5.2: Mannerheim (second from left) as singer Aulikki Rautavaara’s dining partner at the Grand Restaurant Börs, 1936. Mannerheim Museum photo archives. 123

Fig. 5.3: The inauguration of the new Lastenlinna Children’s Hospital in Helsinki, October 1921, featuring Head Nurse Sophie Mannerheim on Mannerheim’s right. Wikimedia Commons/ public domain. 128

Fig. 5.4: Field Marshal Mannerheim on a ride in Helsinki’s Central Park, 1936. Wikimedia Commons/public domain. 132

Fig. 5.5: A page from Mannerheim’s hand-written telephone directory, listing his godchildren, late 1920s. Mannerheim Museum/photo by Toni Piipponen. 135

Fig. 6.1: Mannerheim with his aide-de-camp in front of his private residence, mid-1930s. Mannerheim Museum photo archives. 137

Fig. 6.2: Mannerheim as a guest of the British General Staff, including General Sir Walter Kirke, September 1936. Otava photo archives. 143

Fig. 6.3: Finnish Envoy to Stockholm (and future President of Finland) J. K. Paasikivi at Helsinki Central Station, November 1938. From Polvinen, Tuomo: J. K. Paasikivi.

Valtiomiehen elämäntyö 2. 1918–1939. Helsinki, 1992. 150

Fig. 6.4: The “Insurance” Man: Soviet bear knocking on the door of the Baltic states, a satirical cartoon in The New York Times, autumn 1939. From Churchill, Winston: Min bundsförvant Berlin, c. 1941. 157

Fig. 7.1: Molotov cocktail. Photo from the Finnish Front during the Winter War, early 1940. SA-kuva | Finnish Wartime Photograph Archive. 163

Fig. 7.2: Mannerheim at his desk at Headquarters in Mikkeli, January 1940. SA-kuva | Finnish Wartime Photograph Archive. 169

Fig. 7.3: The first Commemoration Day of Fallen Soldiers at the war memorial in Joensuu, 19 May 1940. SA-kuva | Finnish Wartime Photograph Archive. 179

Fig. 7.4: see List of Maps.

Fig. 7.5: A menu and guest list handwritten by Mannerheim for a lunch for the British Minister-Plenipotentiary to Helsinki, Sir Gordon Vereker, on 15 December 1940. Mannerheim Museum photo archives. 187

Fig. 8.1: Finnish postage stamp depicting Field Marshal Mannerheim, 1941. Mannerheim Museum/Maria Englund. 191

Fig. 8.2: Finnish infantry crossing the 1940 border (defined by the Moscow Peace Treaty), July 1941. SA-kuva | Finnish Wartime Photograph Archive. 197

Fig. 8.3: Mannerheim gazes eastwards over the Karelian Isthmus from Mainila hill, September 1941. SA-kuva | Finnish Wartime Photograph Archive. 201

Fig. 8.4: Hitler and Mannerheim on the Marshal’s birthday, 4 June 1942. Finnish Heritage Agency HK19710326:13 (Creative Commons CC BY 4.0). 205

Fig. 8.5: see List of Maps

Fig. 8.6: The University of Helsinki’s Main Building in flames after being struck by a bomb on the night of 26–27 February 1944. SA-kuva | Finnish Wartime Photograph Archive. 215

Fig. 9.1: The freshly appointed President Mannerheim inspects the guard of honour in front of Parliament House, 4 August 1944. SA-kuva | Finnish Wartime Photograph Archive. 220

Fig. 9.2: Gertrud Arco-Valley (née Wallenberg) and Mannerheim in Central Europe, 1949. Wikimedia Commons/public domain. 231

Fig. 9.3: see List of Maps.

Fig. 9.4: Mannerheim’s funeral procession passing by the Swedish Theatre in the centre of Helsinki, 2 February 1951. Mannerheim Museum photo archives. 239

Fig. 10.1: Mannerheim on the eve of the Continuation War. Satirical cartoon by Heikki Paakkanen, 1991. From Paakkanen, Heikki: Suomi sodassa 1939–1945. Helsinki, 1991. Published with Heikki Paakkanen’s permission. 255

Fig. 10.2: President Kekkonen lays a wreath at the newly unveiled equestrian statue of Mannerheim, 4 June 1960. From von Fersen, Vera: Mannerheim-stiftelsens historia 1945–1951–2001. Mannerheim-säätiön historia. Helsinki, 2007. 257

Fig. 10.3: Monumental: Pekka Vuori’s apt summation of the mythology around Mannerheim, 1994. From Paakkanen, Heikki: Suomi sodassa 1939–1945. Helsinki, 1991. Published with Heikki Paakkanen’s permission. 264

FOREWORD

Every book has its own history. This particular one has its origin at a lunch in the mid-2010s at the Helsinki Bourse Club with the grand seigneur of the Finnish book trade, Professor Heikki A. Reenpää (1922–2020). Before we had even begun the main course, he had proposed that I should write a new concise biography of Gustaf Mannerheim, Marshal of Finland, and one of the few Finns renowned internationally. The idea had certainly crossed my mind before, since I had spent almost three decades researching, writing and lecturing about the Marshal. Until that point, however, I had always put it off, as I had not felt ready for such a demanding undertaking.

In all probability, I would have gone on putting it off for the rest of my life, if the suggestion had not come from Heikki A. Reenpää himself. It was he who had helped bring out the Finnish edition of the Marshal’s memoirs in the early 1950s, published by Otava. Reenpää had afterwards nurtured a great number of other Mannerheim books to fruition at Otava, which meant that his proposal was too tempting to resist. To put it simply, I wanted to join the publisher’s long line of Mannerheim authors, the first of whom had been no less than the Marshal himself.

Writing a biography of Mannerheim (1867–1951) was therefore both a rewarding and a demanding task. It was not only that his impressive life’s work as an Imperial Russian officer, a Finnish military commander and head of the state covered a crucial era in the formation of modern Europe. It was also the way Mannerheim conducted this journey—so dramatically and sometimes even unpredictably that, to keep the grip concise, I tried to follow Lytton Strachey’s advice, in the foreword to his classic study Eminent Victorians: the first duty of the biographer is to preserve “a brevity which excludes everything that is redundant and nothing that is significant”.

Another challenge, of course, was to keep a balance between critical distance and empathic understanding, not least because Mannerheim still can inspire either unconditional admiration or deep irritation among many of my countrymen. It is inevitable that my perspectives and conclusions bear the imprint of my own background and career. Particularly relevant here is the fact that I was curator of the Mannerheim Museum in Helsinki in the 1990s, which taught me much about both the panegyric and demonising tendencies in the politicisation of Mannerheim’s story, whether in historical research or popular commemoration.

Mannerheim was born into one of Finland’s leading noble families, which lost all its fortunes due to his father’s fatal shortcomings. After these and some other early difficulties, he forged a splendid career in the Russian Army, coming into close contact with the Imperial family and serving for three decades. That fascinating chapter in his life ended abruptly when the Russian Revolution of late 1917 brought him back to Finland, which declared its independence after 108 years as a Russian Grand Duchy. When the revolution spread to Finland in 1918, Mannerheim was appointed Commanderin-Chief of the counter-revolutionary Finnish White Army, which ultimately triumphed over the Finnish Red Guards.

After a short period as interim regent of the newborn Finnish state, Mannerheim retreated into a comfortable life as a national hero, living off a fund raised by the people for his income—until the Second World War saw him return to the heart of power, picking up where he had left off two decades earlier. Now in his seventies, he once again took to the world stage, now as Commander-in-Chief of the Finnish Army; and, for the second time, steered his country through the Armageddon of European war with its independence intact. The price Finland paid for its survival was harsh: the death of almost 100,000 soldiers, and a military alliance with Hitler’s Third Reich between 1941 and 1944, for which Mannerheim held responsibility as commander-in-chief. Not surprisingly, the Marshal has been both adulated and vilified for the decisions taken during these troublesome years.

Mannerheim’s life and legacy are thus closely intertwined with the dramatic twists and turns of Finland’s history as an independent state. For a long time, the concept of geopolitics as a meaningful

way to understand events was severely tarnished by the experiences of the two world wars. But, gradually, the concept has become relevant again. As we have seen in Ukraine, geography, along with the control of strategically important territories and trade routes, simply continues to be a decisive factor in international politics. Mannerheim seems almost an embodiment of this truth. Finland’s border with Russia constitutes the longest and, in some senses, the sharpest frontier between civilisations in Europe; as such, the country has often been a pawn on the international chess board. Even to this day, geopolitics still has a considerable impact on Mannerheim’s reputation in Finland: how the Second World War is commemorated and how the Marshal is viewed often go hand in hand.

The first editions of this book were published in Finnish and Swedish in June 2017 for the 150th anniversary of Mannerheim’s birth. Foreign interest in the Marshal has only grown since then, with the biography brought out in Estonian and Russian in 2018 and 2020, respectively. With this English translation, it has now been published in five languages, which I am naturally proud of and thankful for.

I warmly thank Dr Richard Robinson for his precise and nuanced English translation of the manuscript. I am indebted to my editor Lara Weisweiller-Wu for her thorough and engaged editing of the manuscript, which made it more accessible for Western readers. I must also express my gratitude to Dr Hannu Linkola, who draw the six maps that so vividly uncover the different geopolitical contexts of Mannerheim’s career. This translation has been funded by the Mannerheim Foundation, for which I am also grateful.

Henrik

Meinander Helsinki, January 2023

CHILDHOOD AND ADOLESCENCE

Unrest and Upheaval

“At a ¼ past 7 in the evening Hélène had a healthy baby boy.” So reported Louise von Julin to a close relative on 4 June 1867, after she had assisted in the birth of her stepdaughter’s third child. The grandmother had washed the newborn, and described him as “kind and jolly”, which were not exactly qualities for which the boy would always come to be known later in life, serving as a reminder that we all start out as blank slates. The birth took place in Louhisaari Manor in Southwest Finland, a stately stone mansion from the seventeenth century which had been a home for the noble family since its purchase by Carl Erik Mannerheim in the 1790s. While the baby’s delivery went smoothly, the mood was sombre, for the newborn’s aunt had only recently died in childbirth. Hence the christening, held three weeks later on Midsummer’s Eve, was solely for the immediate family, with the grandmother as the only godmother in attendance.

In a letter to her sister in Sweden, Hélène Mannerheim complained that “not a single person was glad about” the boy’s arrival. He would, however, go on to become more famed and fêted than anyone else in twentieth-century Finland. He was baptised Carl Gustaf Emil, but was usually called Gustaf. The first two names had been borne by many of his forefathers; the last came from his oldest uncle, ironmaster Emil Lindsay von Julin, who would later try to guide his nephew down the right path with the help of moral insights from British literature. While Mannerheim could have arrived into the world at a more propitious moment in history, there is no doubt

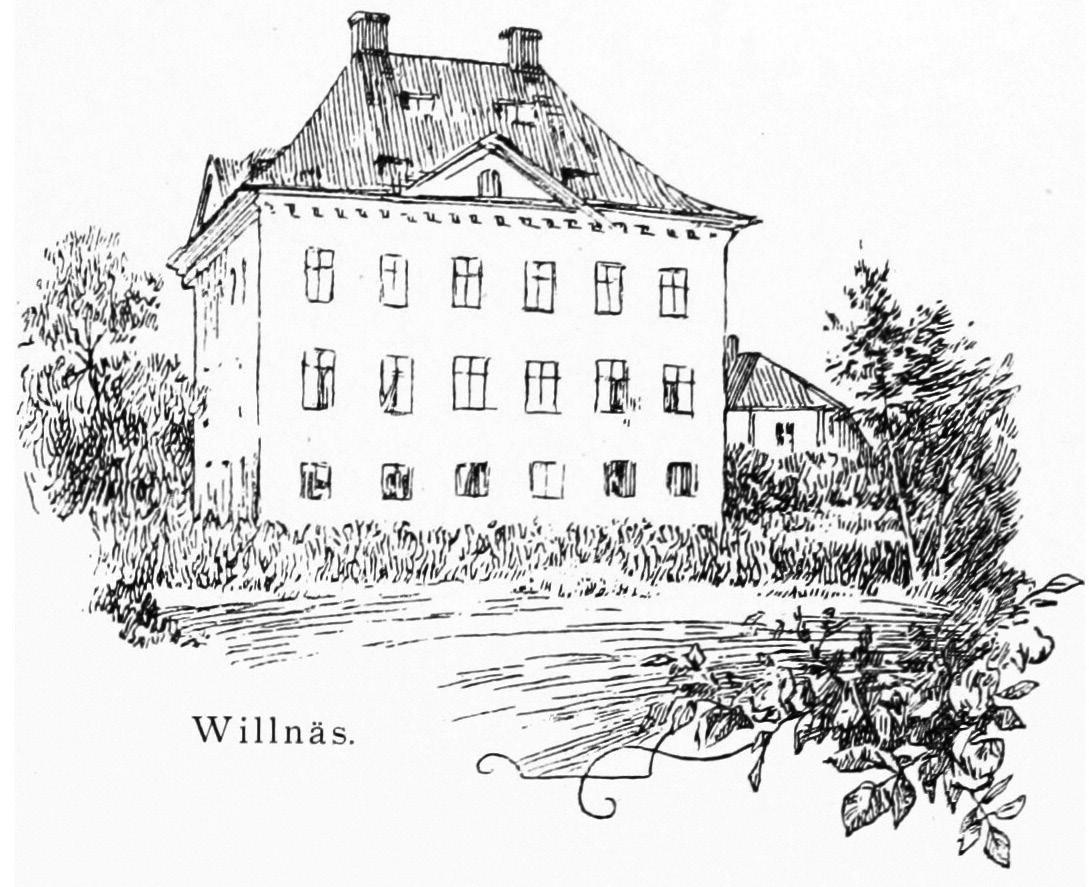

1.1: Louhisaari Manor, Gustaf Mannerheim’s birthplace and childhood home.

that he was born with a silver spoon in his mouth. On numerous occasions in his early career, he would get himself out of a tight spot with the aid of his uncles’ money and his noble relatives’ contacts, above all those in the centre of the Russian Empire, St Petersburg.

But let’s not jump forward in Mannerheim’s life without first examining how the world and Finland looked in the mid-1860s. Tired truism it may be, but these years really were a time of upheaval in many respects. The Crimean War of the 1850s had resulted in Great Britain surpassing Russia as Europe’s leading Great Power. Over the next two decades, and thanks to its technological and military advantages, the British Empire expanded faster than any other before or since, in the process spreading its innovations and the British social ideal to other parts of Europe. As the world’s leading industrial and colonial power, it stood to reason that Britain was the foremost advocate of a liberalised global trade and a free civil society, one that not only gave its citizens

Fig.

freedom of speech and association, but also the right for a growing number of them to vote.

In the same year that Mannerheim was born, a parliamentary reform was implemented in Britain that significantly broadened the franchise. The reform did not seem to impress Karl Marx in the slightest, for 1867 was also the year when the socialist, who had moved from Germany to England in 1849, published the first—and certainly the most influential—part of his work Das Kapital. Due to the boom in newspaper publishing, the 1860s witnessed a formidable eruption of ideas and ideologies about what the future of society could and should look like. The majority of those seeking reform had freedom as their common cause, but they became increasingly fractured as to whether the freedom should be individual, national or economic in nature.

Across Europe and North America, more and more resources were being invested in railways, industry and steamboats. In February 1867, the first ships sailed through the French-built Suez Canal. The canal company was soon purchased by the British, and the European colonial powers tightened their grip over East Africa and Asia via this new waterway. Also noteworthy is the 1867 International Exhibition, held in Paris and opened in April, which even featured a Finnish exposition in the Russian pavilion. On the very date of Mannerheim’s birth, Helsingfors Dagblad featured a long report from the exhibition, which paid special attention to the public demonstrations of “improvements in the social, moral and physical standing of the working class in France”.

The modest Finnish products and artworks told a very different story. In the mid-1860s, Finland was one of Europe’s poorest countries, and the plight of its inhabitants was heightened by the succession of extremely cold summers that struck the northernmost parts of Europe between 1865 and 1868. These led to crop failures, famines, epidemics and, ultimately, to high death tolls, not least in the isolated and capital-poor Finland, where more than 100,000 people died. So, while the display cases at the world fair were abundant with culinary delicacies, food shortages in the Finnish countryside were degenerating into a humanitarian catastrophe. The spring of 1867 came extremely late, and by August the arable land was again being assailed by hard frosts at night. Although the Senate had,

at long last, taken foreign loans to buy grain from abroad, the early onset of winter meant there was no time for it to arrive before the sea froze and put a stop to all shipping traffic.

The irony of fate was that, in this case, ultimate responsibility for the government’s fatal procrastination lay with J. V. Snellman, a member of the Senate’s Department of Finance. He was at the vanguard of the burgeoning Finnish nationalist movement—Fennomania—and in previous years he had succeeded in forcing through a number of decisions and reforms that were extremely important for Finland’s development. In 1863, after a 54-year wait, the Russian Emperor had agreed that the Diet of Finland, the country’s chief legislative body, could begin to meet regularly. Also in 1863, an imperial edict was issued—on Snellman’s initiative—declaring that Finnish would gain equal status with Swedish as an official language within twenty years. In the same period there began a comprehensive modernisation of the country’s education system, and the recently introduced Finnish currency (markka and penni) was tied to the silver standard rather than to the rouble.

All these reforms caused cracks to emerge in the established social order, within which many previous generations of the Mannerheim family had reached high positions. The family’s progenitor was the merchant Henning Marhein from Hamburg: his son Hinrich, born in 1618, was drawn north to Sweden, which was a Great Power at the time. He settled first in Gävle, where he worked as a merchant, before later moving to Stockholm and earning his living as a bookkeeper. The following two generations climbed rapidly up the social ranks. Hinrich’s son Augustin was ennobled in 1693 for his contribution to Charles XI’s Great Reduction (in which the Swedish Crown reclaimed land from the high nobility) in the Baltic provinces. In 1768, Augustin’s son, Colonel Johan Augustin Mannerheim, was made a baron. The two generations that followed also included high-ranking officers.

An integrated part of Sweden since the twelfth century, Finland was brought under Russian rule following the Finnish War of 1808–09. The country was designated an autonomous Grand Duchy of the Russian Empire as a result of negotiations in which Carl Erik, Johan Augustin Mannerheim’s grandson, played a central role. As a consequence he was appointed a member of the country’s first Senate,

originally called the Governing Council, and received the title of count in 1824. This title was subsequently held by the head of the family: that is to say, the eldest male family member of each generation. Hence the Mannerheim dynasty became one of the high-ranking families that led the Grand Duchy, in part through high office and in part through many mutually beneficial marriages. This continued until the 1860s, when the aforementioned Diet of Finland began to assemble and the nobility’s privileges were slowly eroded.

As the winds of change sweeping across Europe were finally felt in Finland, one after another of the well-to-do noble families lost

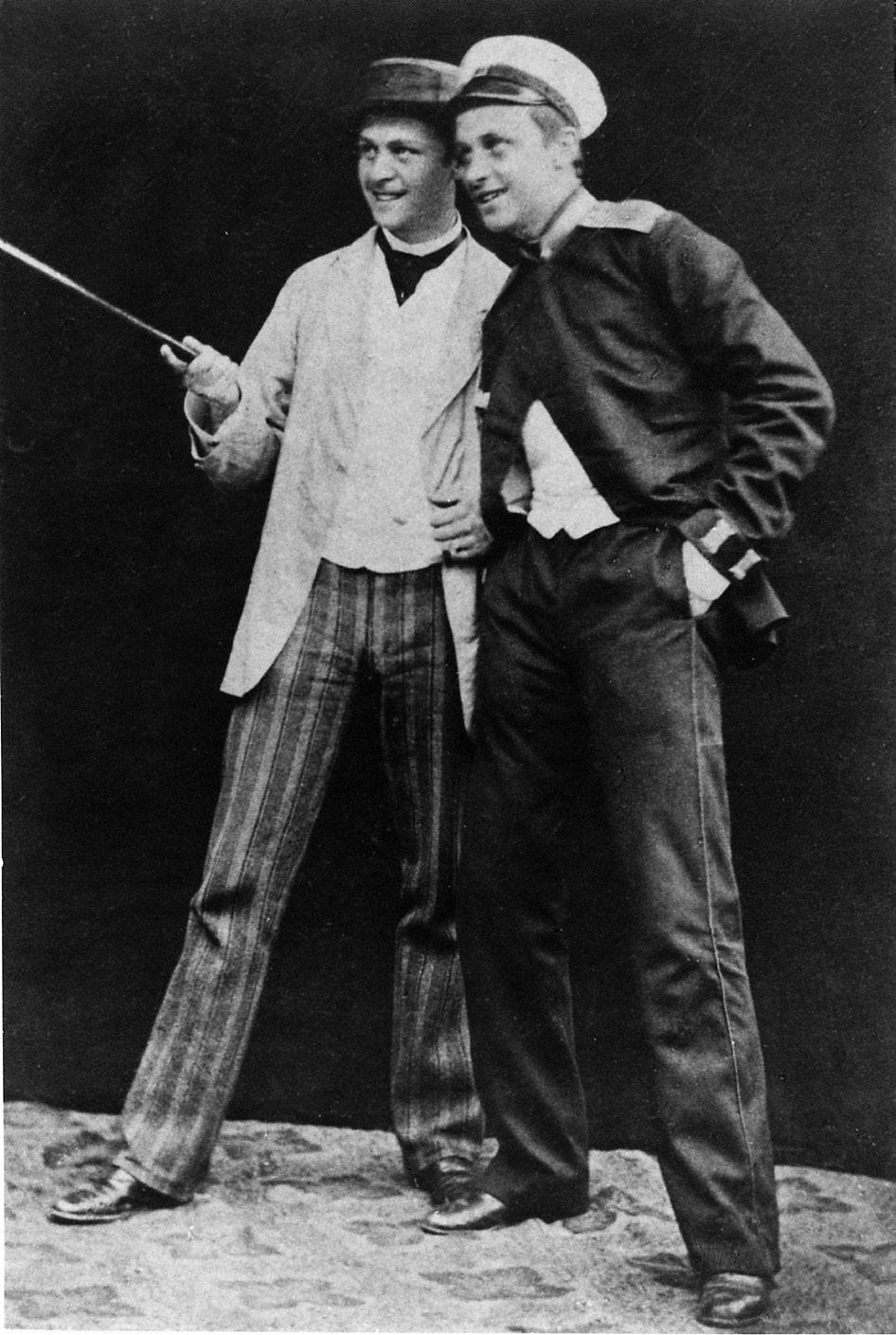

Fig. 1.2: Brothers Count Carl and Baron Gustaf Mannerheim posing cheerfully, 1884.

their social status and financial fortunes. Carl Erik Mannerheim’s son, Carl Gustaf, became a provincial governor and the President of Viipuri’s Court of Appeal, but his grandson, Carl Robert, did not fare so well. In the late 1850s, he ruined his reputation among the powers that be in St Petersburg by joining a clique of liberals critical of the regime, thereby losing all prospects of a successful career in the Russian bureaucracy. Instead, Carl Robert tried his luck as an entrepreneur in the nascent forestry industry.

But in common with many of his standing, Carl Robert completely lacked the necessary qualities to prosper as a capitalist and industrialist. His childhood friend, the upper-class liberal Anders Ramsay, would candidly recall in his memoirs, Från barnaår till silfverhår (1904–07; From Child’s Play to Going Grey), how he himself managed to bankrupt not one but two large businesses. In Carl Robert’s case, his unsuccessful investments and half-baked ventures were exacerbated by his accumulation of gambling debts. By 1866, straitened circumstances compelled him to begin selling his and his wife’s shared heirlooms one after another. Fourteen years later this culminated in a catastrophe that would leave its mark on the whole family.

Hélène von Julin’s brothers and relatives could surely not have imagined that everything would end so badly when the young Count Mannerheim eagerly proposed to her in autumn 1862, even though they were somewhat hesitant in approving the couple’s marriage. Carl Robert was undeniably handsome and charming, but also notorious for his outspoken political views and lavish lifestyle. This contrasted with the Julins’ frugal existence, which was more in keeping with that of merchants or industrialists than the upper class. Indeed, although the family had been ennobled in the late 1840s, the railways, mechanical workshops and estates that they ran in LänsiUusimaa continued to prosper, to the benefit of the whole region. In spite of her family’s doubts, Hélène got her way, and the couple’s wedding was celebrated at Fiskars’s factory on New Year’s Eve 1862, with guests including a number of high-ranking officials and liberal cultural personalities.

Unions of this kind between ancestry and money were customary at this time in Finland, as elsewhere in Europe, and if everything went well they could work to the advantage of both sets of relatives.

Hélène and Carl Robert’s matrimony initially appeared to have fulfilled the young couple’s romantic expectations. As the family grew, Hélène was increasingly tied to the Louhisaari Manor, which became a meeting place for the Mannerheim clan. It often proved attractive to her relatives, too, such as when Grandma Louise helped with the birth of Gustaf during the exceptionally cold early summer of 1867. The eldest child of the brood was Sophie, who was born in 1863 and who shouldered a large responsibility for her younger siblings from an early age. Two years later, their son Carl was born, who inherited his father’s countship; then came Gustaf and after him a further four children between 1868 and 1873: Johan, Eva, Annica and August.

Mannerheim’s early years at Louhisaari are described in idyllic terms in just about all his biographies. But what did his boyhood surroundings actually look like? The stone manor that housed the large family, its guests and servants comprised three storeys, plus attic and cellar spaces. The interior was fairly typical for a manor of the period. The accumulated furniture, pictures and other household paraphernalia of past generations were interspersed with the occasional object that reflected the current inhabitants’ interests and characters. In Carl Robert’s case, his personal additions included a choice art collection of the period’s foremost Finnish painters. The strict symmetry of the main building’s north-easterly entrance hall contrasted with the English park that stretched out to the southwest. Behind the park could be spied Louhisaari Bay, a broad archipelago where the children spent their summers happily swimming, rowing and sailing.

There are numerous anecdotes detailing the young Gustaf’s wild nature and his almost foolhardy bravery. Yet it is pertinent to consider the extent to which he greatly differed from other healthy and boundary-testing boys of his age. Perhaps his unruliness was a way for him to assert himself in the shadow of his elder brother, Carl, who was often praised for his level temperament. Perhaps he took the lead from his father, whose vivacious but unstable nature stood in contrast to his mother’s steady and discreet disposition. Or perhaps it was simply that his father was far too rarely at home to instil discipline in him.

The Mannerheim siblings would later reminisce about their childhood at Louhisaari with gratitude, always emphasising the memory

of their mother, whose love and devotion they all attested to. In contrast, their father’s contribution was typically and tellingly absent from such recollections. It is no accident that Mannerheim chose to start his memoirs from the year 1882, when his career in the military began. Much later, Gustaf’s younger brother Johan wrote to his fiancée that his parents’ marriage during his childhood had been a horrible failure: “I would in no way induce myself to experience all the misery, that I, as a child, have witnessed.” Johan and his betrothed kept this in mind and went on to spend a contented life together in a manor in Östergötland in Sweden. The other children were not quite as successful in shaking off the traumatic experiences of their parents’ abrasive marriage, not least because Carl Robert’s gross mismanagement of many generations’ accumulated fortune and reputation caused the family to fall apart. This left the deepest impression on Sophie and Gustaf, who would themselves both enter into a short-lived wedlock and never remarry.

In autumn 1879, the bankrupt Carl Robert, together with his lover Sofia Nordenstam, fled to Paris. True to form, he did not bother to enquire about the mess that he had left behind. A year later, all his remaining property was sold at auction to cover at least some of his creditors’ claims. Fortunately, Carl Robert’s sister, Eva Vilhelmina Mannerheim, was able to buy Louhisaari, which allowed the family to continue to spend their summers at the manor, although this was, of course, scant comfort. Hélène and the younger children were compelled to move to their grandmother’s manor house, Sällvik, in Pohja, while the older children continued their schooling in Helsinki and Hamina.

Gustaf had begun his schooling in Helsinki in 1874, and while there his unruly conduct had continued to attract attention. A few years later, in autumn 1879, he was expelled from the prestigious Helsingfors Lyceum—sometimes also called the Böökska lyceet—for having broken a number of windows in the city with some friends. As a consequence he was sent instead to Hamina, the home of the Finnish Cadet Corps; he passed its entrance exam in summer 1882, after a couple of years in the local grammar school. This was neither an unusual nor an ignominious solution for a Finnish noble family in the nineteenth century; especially not if the family had a military history or was in straitened circumstances, and even less so if the

boy had shown himself to be too disorderly for a civil education. Around 3,000 sons of the nobility passed through the corps during its years of operation between 1818 and 1903, and so made up the majority of its 4,000 graduates. Around 500 Finns reached the rank of general or admiral in the Imperial Russian Army and Navy.

Since autumn 1879 was also when his bankrupt father left the family high and dry, it was hardly a coincidence that Gustaf’s bad behaviour degenerated and led to his expulsion from Helsingfors Lyceum at that particular moment. And as the family’s possessions were sold off and rumours spread of Carl Robert’s exploits in Paris, the social pressure became too much for Hélène, who died in January 1881 from a heart attack. It has been reported that the children welcomed Carl Robert with open arms when he came back to attend her funeral. However, when he married his mistress a few years later and returned with her to Finland, their disappointment with him hardened into a lifelong contempt, not least in the case of his eldest boy, Carl. According to hearsay, his sons took to calling him “Count Swine” behind his back.

It should, however, be noted that Gustaf’s relationship with his tarnished father was less condemnatory. It seems the fact that they had both slipped up and suffered setbacks made them more prepared to forgive each other. Upon his return home, his father founded a new business specialising as agents of office supplies, which gradually came to provide him with a modest standard of living. Both father and son were happy to meet when Gustaf was in Helsinki, and they maintained a regular correspondence. As the letters make clear, Carl Robert accepted his son’s career in the Russian military, even though it was increasingly at odds with his own and his other sons’ liberal and constitutional attitudes.

The Cadet in Hamina

In his expansive biography of Mannerheim, Stig Jägerskiöld advances the idea that Gustaf was his father’s son, in the sense that he remained, at heart, a constitutional and liberal patriot throughout his life, even as he later expressed an unwavering loyalty to the Russian Emperor. John Screen, who has likewise written a splendid biography of Mannerheim, is not so convinced that this was the