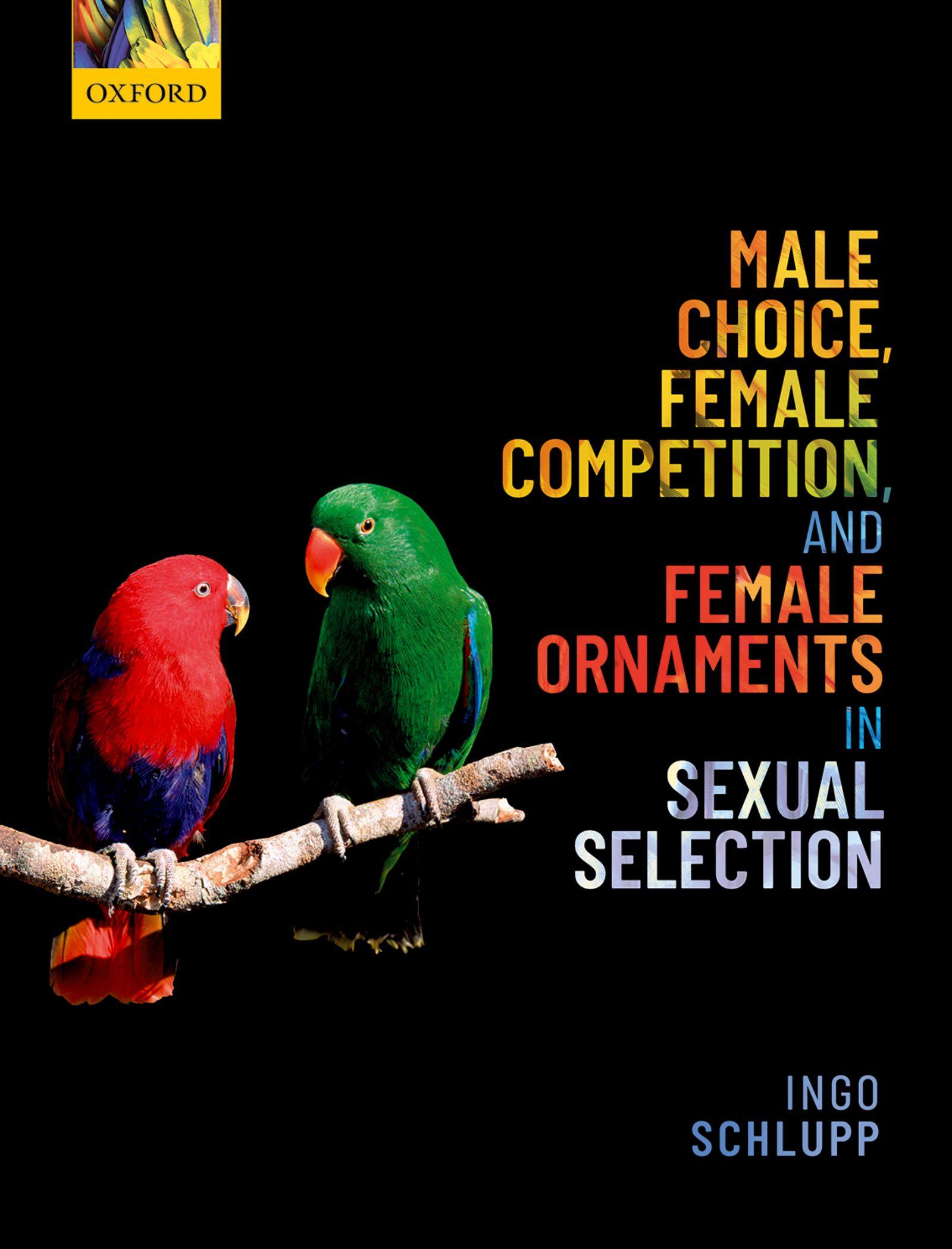

Sexual Selection, Mate Choice, and Competition for Mates

1.1 Brief outline of the chapter

Well over a century ago Charles Darwin redefined biology and introduced the theory of natural selection. One of the problems he encountered was the existence of traits, mainly in males, that seemed to defy the principles of natural selection: they did not aid its bearers in survival and were often outright detrimental. Darwin solved this conundrum by introducing sexual selection. Other than in natural selection where all individuals compete with each other for survival and reproduction, in sexual selection individuals within each sex compete with each other for reproduction. In the original formulation of the principle, Darwin recognized two mechanisms for this: males would compete with each other for access to females, and females would choose mating partners of their preference.

In this opening chapter I want to introduce the topics to be covered in the book, define some basic terms that we will need to understand the subject matter, and define the questions to be asked. My aim for this book is to summarize our growing, yet still comparatively limited empirical knowledge and theory, and to provide suggestions for future research. What interest me most are the relationships between the four forms of sexual selection and their consequences.

1.2 Sexual selection

Sexual selection is one of the most important forces in evolution. Charles Darwin introduced the theory in his revolutionary work On the Origin of Species in 1859 (Darwin, 1859). But as Darwin was working on

his all-encompassing theory of natural selection, he came across many examples of traits that were difficult to explain within his new framework. They were mainly found in males and clearly were detrimental to their bearers. How could selection favor traits that did not contribute to survival? The solution he proposed in 1859 and then in much more detail in another book, The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex in 1871 (Darwin, 1871) was sexual selection. He suggested that males may leave behind more offspring if they had more mating opportunities than others, either because they are favored by females or because they succeeded in competition with other males. We all know impressive examples of these two key mechanisms of sexual selection, female choice and male competition. In an example of the latter, gigantic males fight over access to females in elephant seal (Mirounga angustirostris) colonies. Males compete with each other over harems of females (Leboeuf, 1972). Owing to this, males have evolved a striking sexual dimorphism and are several times the size of the females. Intuitively, most biologists will likely attribute the existence of ornaments and also sexual dimorphism to sexual selection. Later in Chapter 7 I will discuss a few examples where this is misleading. Also, the sexual dimorphism in humans, which is usually attributed to sexual selection, may also be explained by hormonal and developmental effects (Dunsworth, 2020). This idea is by no means widely accepted but provides an example that we need to be cautious when we generalize. Male competition plays out within one sex (intrasexual). On the other hand, in female choice, females in numerous species pick their favorite males out of a line-up of

males who are displaying byzantine dances while showing off ornamental traits, such as colorful plumage, song, smell, and motion patterns among others. Even the giant sperm found in some Drosophila are considered an ornament (Lüpold et al., 2016). A classic example is the tail of the peacock (Pavo cristatus). This particular example goes back all the way to Darwin, who agonized over the peacock’s tail because it was impossible to explain its evolution with natural selection alone. He complained to Asa Gray in 1860 that the “sight of a feather in a peacock’s tail makes me sick” (Hiraiwa-Hasegawa, 2000). While natural selection is somewhat blind to sex (Sayadi et al., 2019), female choice is intersexual and plays out between the sexes. This is all happening to allow individuals to reproduce. The peacock’s tail is also relevant as an example of indirect benefits (Petrie, 1994). Many courtship displays are multimodal (Rosenthal, 2017), and involve multiple sensory channels (Candolin, 2003; Partan and Marler, 2005). A great example of this is the courtship display of the Gunnison sage grouse (Centrocercus minimus), which blends color, motion patterns, and sound (Gibson et al., 1991).

Clearly, finding a partner for reproduction is likely the most important decision any organism ever makes. This is how genes are passed on to the next generation. This applies to direct offspring, and to some degree to offspring of close relatives via inclusive fitness. And, unsurprisingly, mate choice is very complex and complicated (Rosenthal, 2017). It is also a highly interactive process with many different phases, from recognizing a suitable mate to the actual fertilization of gametes. Furthermore, it often seems like an agreeable, almost cordial process, but in actuality is usually fraught with conflict because only rarely do the partners have identical fitness returns (Chapman et al., 2003).

The original definition of sexual selection provided by Darwin has been subject to intense debate and several other definitions have been suggested (Alonzo and Servedio, 2019). All the definitions agree that the hallmark of sexual selection is that it has effects within a sex and highlight differential reproductive success as the key mechanism (Alonzo and Servedio, 2019). A problem with many definitions is that they rely on binary sex roles and assume that we can always assign a male and female role. Sexual

Figure 1.1 Selection in the wild. N equals natural selection, S equals sexual selection, NS equals combined natural and sexual selection (redrawn from Andersson, 1994).

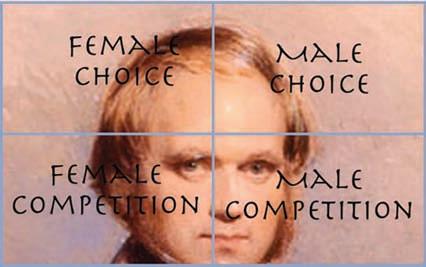

selection can be viewed as a subset of natural selection. Natural selection works on both sexes, although it can work on them separately (Sayadi et al., 2019). To visualize the relationship of natural selection and sexual selection, perhaps one could think of natural selection as the outer layer of an onion. Beneath lies sexual selection, with its four components, female and male mate choice, and male and female competition. These elements and their interplay will determine the reproductive success of an individual (Figure 1.1). One might think that sexual selection theory has been studied enough and is becoming boring, but the opposite is true (Lindsay et al., 2019).

Within sexual selection, two components have received much theoretical and empirical attention: males competing over access to mating opportunities with females and females choosing among competing males. This view, however, appears to leave out some important elements, such as female competition and male mate choice. Male mate choice in particular has been “flying under the radar” for a long time, but recent years have seen a small surge of studies that address what I call the orphans of sexual selection theory: male choice and female competition (Figure 1.2). These two additional elements have been somewhat studied since Darwin’s time, but are far less well documented and understood than female choice and male competition, the two major elements of sexual selection introduced by Darwin.

Sexual selection theory has an interesting history that may provide some more general lessons to be

learned. Male competition was relatively quickly accepted because this aspect apparently was a good fit for Victorian scientists and society (Milam, 2010; Richards, 2017). The notion of a mainly passive female and a knightly competition for them was easier to rationalize than active female choice. Actually, from the very beginning female choice was a tough sell, and Darwin experienced major pushback from his colleagues, including Wallace, who was his ally on natural selection (Richards, 2017). Even Darwin himself, perhaps being a child of the Victorian era, had problems with female choice: he conceived the idea of male competition around 1842, but female choice was not formalized until over a decade later around 1856 to 1858 (Richards, 2017). Darwin uniquely also assigned human men the ability to choose females. This was in contrast to other parts of his theory but has led to the peculiar situation that male mate choice has been a natural topic for evolutionary psychology for a long time—leading to a rich literature on humans, while it was somewhat ignored in other animals.

Female choice finally took a central role in research much later—actually the delay was over a century. To me the late blooming of female choice is an important cautionary tale, showing how societal context influences research and can act as blinders for research. In an early paper, Zuk (1993) summarizes a feminist perspective of sexual selection research and points out how the growing number of female scientists has changed research paradigms, interpretations, and language use to better reflect societal changes. The concept of sex

roles and the stifling effect this has had on the development of the field has also been critiqued (Ah-King, 2013a, 2013b; Ah-King et al., 2014). A proposed solution to this is to use the term “chooser” (Rosenthal, 2017) for any individual that is selective in mate choice. It is important to note that the emphasis is on individual behavior, not sex roles that apply to populations or species. A recent book on mate choice (Rosenthal, 2017) used this terminology and replaced male and female with neutral terms, such as “chooser” for individuals that select mates and “courter” for individuals that compete for mates and display to choosers in some form. This circumvents loaded terminology such as “sex-role reversal” for mating systems in pipefishes, where males are choosers (Berglund and Rosenqvist, 2003).

This struggle with terminology reflects a very general phenomenon. It is very important here to realize that language is very powerful, and in itself may influence how we understand important concepts such as time (Boroditsky, 2001). For example, mate choice is sometimes used as shorthand for female choice (Dargent et al., 2019), effectively removing male mate choice from consideration. Generally speaking, there is always a very tight connection between the science that is done and the current condition of society. This can take many different shapes and forms, such as directly outlawing certain research, like stem cell research using cell lines originating from abortions in the United States based on moral and religious grounds mainly outside of the scientific community, but with clear input from the scientists (McLaren, 2001; Nisbet, 2005). In the United States, legislation banning stem cell research was the outcome of an intense public debate over these values (Ho et al., 2008). Other countries, based on their values and laws, allow stem cell research. This shows how the values of societies, and the resulting governments and administrations, set the framework and the limits for what scientists are allowed to do. Some research, such as studies on gun violence in the United States, is not outright forbidden but may not be funded by public monies. This ban goes back to the so-called Dickey Amendment, which was introduced by US House Representative Jay Dickey (Jamieson, 2013), a Republican from Arkansas, in

Figure 1.2 Complete matrix of sexual selection.

response to a 1993 paper (Kellermann et al., 1993) showing a connection between the presence of a gun in a home and the risk of homicide. Subtler and always well intended, but no less consequential, are the policies set by funding agencies that steer research in certain directions by allocating or taking away funds. But even without outside influences the science actually conducted is obviously influenced by the relevant societal context. This requires a constant engagement of scientists and society on many important issues. A recent example would be the use of cloning technology on humans (Liu et al., 2018), or the ongoing debate on gene-editing techniques using clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)-Cas9. These examples also highlight an important aspect of the feedback loop between society and the scientific community, namely that oftentimes scientific discovery happens a long time before a meaningful discussion of its implications can be held. While some of these discussions are held in public, and sometimes loudly, many discussions and disputes are more internal and never reach a general audience.

Does this also apply to aspects of sexual selection? One reason for the relative lack of studies on male mate choice and female competition could be that based on Darwin’s thinking and cemented by subsequent work, we arrived at a situation where stereotyping of sex roles (Green and Madjidian, 2011) has prevented advances in theory and experimental work, as was suggested for other aspects of sexual selection theory (Ah-King et al., 2014). But maybe the field is simply lacking a better conceptual framework and adequate experimentation.

1.3 Why choose or compete?

Mate choice and competition for mates seem almost ubiquitous, but there is a cheap alternative to choosing, which is simply not to choose and to mate at random. This is, for example, widespread in marine invertebrates. One example is the palolo worm, Palola viridis. This polychaete releases gametes (Caspers, 1984) into the open sea and apparently the mating is random, although the release of gametes is highly coordinated and seems regulated by

the lunar cycle. One caveat here is that potentially choice may be cryptic and mate selection actually happens at the level of the gametes (Chapter 6).

The majority of metazoans, however, exercise either choice or competition for mates, or both. In other words, the costs of choice or competition must be smaller than the benefits. In addition to the easily observed costs of choice and competition, there is a large difference in the initial investment into gametes. Essentially, the argument for choice and competition is an ecological one, but it is based on the evolution of anisogamy—gametes of different sizes (Chapter 5). The traditional view holds that the sex that invests more into gametes, females, usually evolves to be the limiting resource for the other sex, males. Males, on the other hand, invest very little into the gametes and are the limited sex. In a way the two sexes we recognize use very different strategies and packaging to pass on almost equal amounts of DNA (Scharer, 2017).

Early work in sexual selection focused much on male competition (Milam, 2010), largely ignoring female choice. Even the view of aggressive males and coy females, and the associated stereotypical sex roles, are a relatively modern construct and did not really originate until after World War II (Milam, 2012). Interestingly, male mate choice saw some important early work because it was thought to be relevant in speciation, and species recognition. These studies were based on the view of the species as unit of selection and often found only weak support for the predicted male preference of their own species (Milam, 2010). As just one example, Haskins and Haskins published studies of male mate choice in guppies and some close relatives and reported evidence for male preferences for conspecific females (Haskins and Haskins, 1949, 1950). Another contemporary record of male mate choice in the context of species recognition was published by Hubbs and Delco (1960). In this paper the authors describe a conspecific preference in four species of the genus Gambusia, a group of livebearing fishes. They showed that most species indeed show the predicted species preference, but that Gambusia affinis does not.

However, the roots for modern sexual selection theory were put down by Hamilton in the 1960s when he revolutionized the way we think about the

unit of selection. Until then biologists worked under the assumption that selection operates on the species, but Hamilton argued that it is the gene that is under selection (Hamilton, 1964a, 1964b), leading to a Kuhnian revolution and a complete paradigm shift (Kuhn, 1962). A precursor for Hamilton’s idea was found in the works of Haldane, but Hamilton is the one who perfected the argument.

A little later, in 1972, Trivers presented his influential theory of parental investment (Trivers, 1972). He noted that the sex that invests more in their offspring usually evolves to be the choosier sex. Based on Bateman’s earlier work (Bateman, 1948) on the consequences of anisogamy in Drosophila, he argued that females initially invest more into their gametes compared with males, and typically benefit from carefully selecting the partner they have offspring with. Females are limited by the number of eggs or reproductive events they have, whereas the male potential reproductive rate (PRR) is only limited by the number of eggs they can fertilize. Theoretical models have confirmed the role of anisogamy in the evolution of sex roles (Lehtonen et al., 2016). This makes the ecology of investment in offspring a key element in sexual selection. The majority of the research has since focused on female choice, with less focus on male choice. The above line of argument firmly established the concept of sex roles, which has been used widely, but has also been criticized as hindering research into phenomena outside of these sex roles (Hrdy, 1997; Hoquet, 2020). Typically, females can maximize their reproductive success by carefully selecting the best available male. By contrast, males are generally assumed to be far less discriminatory and should be able to maximize their reproductive success by mating with as many females as they can. This idea is captured in their often different PRR. While this view is empirically very well supported, it is also incomplete, because it does not account for the possibility of male mate choice and female competition. This has been pointed out by several authors and observations of male mate choice are now more abundant, as is theoretical literature (Krupa, 1995; Bonduriansky, 2001; Servedio and Lande, 2006; Servedio, 2007; Barry and Kokko, 2010; Edward and Chapman, 2011; Fitzpatrick and Servedio, 2018) (Chapter 3).

The notion of sex roles has an additional consequence. It creates the impression of essentially binary sex roles. However, in humans we know very well that the situation is much more complex than that. In other animals we know about—for example—hermaphrodites and their sperm trading (Michiels and Bakovski, 2000), about sex-change in fishes (Ross et al., 1983), and also same-sex behavior in general (Poiani, 2010), but one wonders how much additional complexity we are missing in animal sexuality.

1.4 Mate choice

As I said above, mate choice can be viewed as a subset of sexual selection theory, which itself is a subset of natural selection as defined by Darwin, first in On the Origin of Species (Darwin, 1859) and in great detail in The Descent of Man (Darwin, 1871).

1.4.1 Female choice

It is widely accepted that females choose their mating partners, but what is the basis for that? Ultimately, the basis for our understanding of sexual selection is the assumption that ecology drives the evolution of competition and choice. There are two important facets to consider here. The argument for females being the choosier sex is based on their very large investment into gametes. Nonetheless, there are many species, including humans, in which males invest strongly into mate choice, courtship, or some aspect of raising their offspring (Buss, 2015). Such investment can level the playing field and might allow for male mate choice to evolve. This is particularly clear when considering the evolution of so-called “sex-role reversed” species, such as pipefish (Rosenqvist, 1990; Mobley et al., 2011), or tropical birds like jacanas (Emlen et al., 1989) and Nordic birds like phalaropes (Schamel et al., 2004), but it applies to all species. This said, it is also clear that females in many species continue investing into their offspring, potentially erasing all compensatory investment by males. Based on investment relative to the other sex, a broad-scale pattern of intersexual choosiness has evolved. On the other hand, males compete with other males for

reproductive opportunities and, if a male increases his fitness by being more selective as compared with other males, male mate choice could evolve. What are the main reasons for females to choose? There are direct and indirect benefits. Females— and also males as I will argue later—often choose partners that provide them with some form of a direct benefit. Or they choose males that confer an indirect, genetic benefit to their offspring.

Direct benefits are relatively easy to understand. Females select males that make a direct contribution to their offspring. This can be a space that allows females to forage or nest. It is very common for males to provide a nuptial gift to the female, like a prey item in scorpionflies (Panorpa cognata) (Engqvist, 2007) and other insects (Hayashi, 1998; Karlsson, 1998), or a large spermatophore, which may contain nutrients or water. This is common in many insects, including katydids. Often, the time a male is allowed to mate and transfer sperm to the female is directly correlated with the time during which the female is consuming the nuptial gift. Longer copulations lead to increased paternity (Vahed, 2006). In extreme cases the male itself becomes the nuptial gift. This has evolved several times independently and is adaptive in systems where the male has a very low probability to mate a second time. This sexual cannibalism is found in some spiders (Elgar and Schneider, 2004) and in many species of praying mantis (Barry et al., 2010). Other forms of direct benefits may include male parental care (Amundsen, 2003), provisioning of offspring (Badyaev and Ghalambor, 2001), or guarding eggs or nests (Reyer, 1984; Mol, 1996), among many expressions of paternal care. In general, females can benefit from selecting males that show good parenting ability. This is also well documented in humans, where females show preferences for mates with higher available economic resources (Mulder, 1990) and many other personality traits including ambition or stability, as well as a number of physical attributes (Buss, 2015). Not only women appreciate men that can solve problems and show cognitive ability: a similar preference was found in a small bird, the budgerigar (Melopsittacus undulatus) (Chen et al., 2019).

The role of indirect benefits is more difficult to study. In many cases female choice (or at least

preferences) has been documented although males provide no direct benefits to the females. This is a conundrum because it is difficult to understand why females should be choosy, especially if choice is costly. Furthermore, how do male ornaments evolve under this scenario and what information do they provide for the females? Several theories have been suggested to explain this. First, ornaments could evolve to indicate good health to females and/or the ability of males to resist parasites (Hamilton and Zuk, 1982). Individual female preferences for males may aim at maximizing compatibility. This is different from a model where we assume that females have uniform preferences for more or less the same traits. Compatibility has especially been demonstrated in preferences based on the major histocompatibility complex or MHC (Wedekind, 1994; Kurtz et al., 2004). This complex of genes is important in immunodefense. Consequently, females often prefer to mate with a male that will give a female’s offspring the highest diversity for the MHC (Aeschlimann et al., 2003), which plays a crucial role in immunodefense. Interestingly, this is thought to operate in humans, too (Milinski and Wedekind, 2001; Milinski, 2006). Second, they could simply indicate that the bearer of ornaments is a good survivor and may pass on viability genes to his offspring (Reynolds and Gross, 1990). Third, under models of “runaway sexual selection,” male traits and female preference become genetically coupled leading to sons that show the ornament of their father and daughters that express their mother’s preference (Kirkpatrick and Ryan, 1991). Finally, under “chase-away selection,” females do not derive a benefit from choosing, but the male ornament exploits a pre-existing sensory bias in the females (Holland and Rice, 1998). Each of these hypotheses has some support, but it is much more limited than the evidence for direct benefits. For example, in bitterlings (Rhodeus amarus), a fish that lays its eggs in mussels, sperm is also regarded as an ornament, and female preferences are based on small amounts of sperm released prior to actual matings (Smith et al., 2018), suggesting that chemical communication might the mechanism for how females detect differences between males. Smith et al. (2018) also suggested that the benefits for females are indirect.

Preference(idealmate)

Social environment

Sampling constraints

Predator threats

Cognitive limitations

Internal constraints

Local composition of mating pool

Choice (in uenced by local constraints)

Reproduction (actual outcome in uenced by cryptic choice, EPP etc.)

Furthermore, while many signals are fixed, some depend on the current condition of the signaler, reflecting current health, feeding ability, even an extended phenotype, as in, for example, the bower of bower birds (Ptilonorhynchidae) (Patricelli et al., 2006). Also, with experience they improve their skills.

How do preferences translate into actual choice and reproduction? This is not a trivial problem. Having a measurable, even consistent, preference is one thing, but does this actually translate into choice and the production of offspring? The answer is often a clear no. Mate choice is complex and complicated (Rosenthal, 2017). One can view this process as a cascade starting with a preference based on an inner template for an ideal mate (Figure 1.3). For many reasons the actual choice is much more constrained. One such reason is that the actual pool of potential mates is spatially and temporally restricted. Also, the female may not be able to wait for a better mate, and eventually has to mate based on internal constraints. This is especially important in seasonal species, like explosive breeding amphibians. Many more factors influence mate choice. For example, another extremely important factor is sexual conflict (Chapman et al., 2003).

Furthermore, mating decisions are often influenced by the social environment (Danchin et al., 2004). In almost every species, mating and all pre-mating interactions happen in a public setting, where multiple types of audiences can have an influence on mating decisions or be influenced by mating decisions (Valone, 2007). Sometimes called audience effects (Matos and Schlupp, 2004; Auld and Godin, 2015), there are a number of social

interactions that can influence mating decisions and have wide-ranging effects. One example would be mate choice copying (Agrawal, 2001; Vakirtzis, 2011; Witte et al., 2015). Mate copying occurs when females or males incorporate information about decisions made by other individuals into their own decision-making. First studied in guppies (Poecilia reticulata) and based on initial models by Losey et al. (Losey et al., 1986; Gibson and Höglund, 1992; Dugatkin and Godin, 1993), this phenomenon has now been discovered in many different species, such as Drosophila, several fishes (Schlupp et al., 1994; Applebaum and Cruz, 2000; Alonzo, 2008), birds (Galef and White, 1998), and mammals (Galef et al., 2008), including humans (Waynforth, 2007). The majority of these studies found mate copying in females, but males have also been shown to copy mate preferences (Schlupp and Ryan, 1997; Vakirtzis and Roberts, 2012). Social influences on mate choice, and mate copying in particular, have important consequences for processes like hybridization and speciation (Varela et al., 2018).

Along the lines of social influence on mate choice, deceptive behavior has also been invoked. In a study using a livebearing fish, the Atlantic molly (Poecilia mexicana) the authors found that males try to mislead other males to make a suboptimal mating decision (Plath et al., 2008).

Finally, not just the current social environment, but learning in general has important impacts on mate choice (Verzijden et al., 2012). Somewhat related to this, I think there will be very interesting data coming out of studies of epigenetics and sexual behavior.

Figure 1.3 Flow chart of the process from preference to reproduction.

Eventually, the cascade from preference via actual mating leads to actual reproduction and maternity or paternity. This final step is made complicated again because often choosers exercise cryptic choice and bias paternity or maternity. Cryptic choice in females happens via selecting sperm after the copulation has ended (Firman et al., 2017). It is also found in pipefishes, where males brood the young in pouches and exercise some control over which offspring is bred to birth via selective abortion (Paczolt and Jones, 2010) based on conditional signals reflecting female quality (Partridge et al., 2009). Cryptic choice is widespread in species with internal fertilization and allows females—at least in theory— to have social partners based on the resources or direct benefits they provide, but seek genetic paternity from males that may provide indirect, genetic benefits. Males may exercise cryptic choice by selectively allocating sperm. This has been documented for example in insects (Reinhold et al., 2002) and in fishes (Schlupp and Plath, 2005).

1.4.2 Male choice

Male choice is not simply the equivalent to female choice with the opposite sign. Female choice can lead to the evolution of traits that are detrimental to their survival, especially when males contribute little or nothing to the offspring. Because females always invest much more in the offspring via their eggs (this is how we define what a female is), it is very difficult to conceive that males would benefit from such selection on females. Males, in that sense are more dispensable, most never reproduce and die as virgins. However, the research methods and programs that have been successfully used to study female choice can also be used to understand male mate choice. Interestingly, Darwin mentioned male mate choice in The Descent of Man (Darwin, 1871), and thought that it was important in humans, but less so in animals (Richards, 2017) (Chapter 3).

Considering the intersexual nature of Bateman/ Trivers sex roles, male choice can evolve when male investment supersedes female investment. This has happened several times, for example, in jacanas and pipefishes, but compared with mating systems where the females exercise choice this situation is

rare (Chapter 3). These mating systems are usually called sex-role reversed.

Male choosiness can also be viewed as relative to other males. If males benefit from being more selective than other males, male mate choice may evolve. Furthermore, male choice can also evolve when the benefit of choice supersedes the cost of choice and when there are differences in the quality of females (Edward and Chapman, 2011). Often this is the case when female quality differs. Then it may be adaptive for males to evolve male mate choice. In other words, male mate choice can evolve even in the absence of male investment (Schlupp, 2018), and also based on differences in sex ratios (Chapter 6).

A corollary of this is that—if males choose—they should evolve to use cues and signals to determine the quality of females, and females would benefit from evolving such traits. Hence, females may evolve ornamentation under male choice, although they are not expected to be as extreme as ornaments in males (Chapter 7). Such cues and signals could be measures of female fitness, but also ornaments and armaments that evolve in females if they compete for males (Berglund et al., 1997; Roth et al., 2014). Even in species where males contribute nothing but sperm to their offspring it can be adaptive for them to discriminate between different females and prefer certain females if the benefits from male choice outweigh the costs. Multiple mechanisms for this have been suggested (Edward and Chapman, 2011), but one easily understood pathway for how male preferences can evolve is in response to differences in female quality, especially fecundity (Chapter 3). In this case males should mate preferentially with more fecund females, or—if they mate with multiple females—mate with the most fecund female first. This idea is easily testable because in many species, including in fishes with indeterminate growth, fecundity is indeed highly correlated with body size (Dosen and Montgomerie, 2004). Patterns that are in agreement with this hypothesis have been found in many species (Chapter 4).

Rowell and Servedio (2009) discuss some of the theoretical conditions under which male choice can evolve and highlight the fundamental difference between female and male mate choice: for males under many circumstances, females are a limiting resource, but males are not a limiting resource for

Reproductive strategy (Mating effort, parental investment, OSR, PRR)

Capacity to mate with available mates Availability of mates

Variation in female quality?

Random mate rejection Male mate choice

Figure 1.4 Flow chart of conditions that may lead to male mate choice. Reprinted from “The evolution and significance of male mate choice” by Dominic A. Edward and Tracey Chapman, Trends in Ecology & Evolution, Volume 26, Issue 12, pp. 647–654 (December 2011), DOI:10.1016 /j.tree.2011.07.012. Reprinted with permission from Elsevier.

females. This difference based on the early investment into gametes remains very important (Bonduriansky, 2001). For example, Fitzpatrick and Servedio (2017) used a population genetic model to argue that male choice will generate only weak sexual selection on females under limited circumstances, essentially saying that male mate choice seems inherently weaker as compared with female choice. In a previous paper Servedio and Lande (2006) provided detailed models for the evolution of male choice in general, also pointing out that the parameter space for the evolution of male choice is limited.

In yet another study (Barry and Kokko, 2010), the authors predict that especially with sequential mate choice (as opposed to simultaneous mate choice),

the evolution of male choice is unlikely. This sets up an interesting tension between theory and empirical studies. The review of male mate choice by Edward and Chapman (2011) proposes a simple flow chart to predict under which conditions male mate choice might evolve. The key parameters for this are a limited capacity to mate with all available females, limited mate availability, and variability in the quality of females. Finally, the benefit of mating has to exceed the cost of choice (Figure 1.4). Especially limited mate availability is an important factor that will influence male choosiness. This limitation can for example be caused by spatial or temporal shifts in the operational sex ratio (OSR). Shifts in OSR can make males the limiting sex either locally, or for a certain time period.

Finally, we have to consider that male choice may be a byproduct of female choice. Basically, the argument would be that the genetic architecture associated with choosing in females is also expressed in males. This idea, a genetic correlation and pleiotropy, is absolutely plausible (Paaby and Rockman, 2013) and should not easily be dismissed. A similar argument is debated for the expression of male-like traits or ornaments in females (Amundsen, 2000) (Chapter 7). If both sexes in a given species choose, it is considered to be mutual mate choice (Johnstone et al., 1996; Servedio and Lande, 2006). It has been hypothesized that females and males negotiate a compromise that is acceptable to both sides (Patricelli et al., 2011). Such mutual mate choice often leads to assortative mating, where partners with trait similarity end up mating. This has been found—for example—in fishes (Myhre et al., 2012), birds (Nolan et al., 2010), and has been studied in humans (Sendova-Franks, 2013; Stulp et al., 2013) (Chapter 3). In zebra finches (Taeniopygia guttata), however, the notion that mutual mate choice leads to assortative mating has been challenged (Wang et al., 2017).

1.4.3 Male competition

Male competition was the first mechanism of sexual selection recognized by Darwin (1859, 1871). Males compete over females because they can benefit from mating with many females, and therefore excluding others from mating opportunities increases their own fitness. Dominant males in general seem to have more mating opportunities (Cowlishaw and Dunbar, 1991). Potentially, female choice also has a role in this, but dominance per se seems to be adaptive (Clutton-Brock et al., 1989). Male competition can take the form of dramatic fights between two males, sometimes to the death, but often less escalated forms of conflict can resolve the situation. On the other side of the spectrum would be sperm competition, which occurs when sperm of at least two males compete for fertilization of eggs, often inside the female’s genital tract.

Especially when open fighting occurs, males often evolve formidable weapons, such as the antlers of red deer (Cervus elaphus) (Clutton-Brock et al., 1989), or the horns of some beetles (Emlen, 1997).

Sometimes the whole body becomes the weapon, for example when sheep ram each other head-on at full speed (Kitchener, 1988). In many cases the fights look somewhat less forceful, for example, when fishes lock their jaws and push and pull on each other (Bischof, 1996). Often, when weapons have evolved, protective structures also evolve to mitigate the potential damage inflicted by opponents. One example for that would be the mane of male lions (West and Packer, 2002). This can also be used to illustrate the dual function that weapons and protective structures can have: they may also be sexual signals and ornaments that females respond to. Male competition is often a very visible and dramatic behavior and one has to wonder if that has biased studies and reporting of the phenomenon. Female competition seems to be subtler and may have been overlooked more often (Rosvall, 2011).

Very often, large numbers of males would have no chance in an open fight. Winning a conflict is mostly determined by size, as demonstrated for the green swordtail, Xiphophorus hellerii (Franck and Ribowski, 1989), and smaller males almost invariably lose. In some species males wait and grow before they challenge another male, but often alternative mating strategies have evolved (Gross, 1996; Oliveira et al., 2008). In these cases, some males try to undermine the mating investment of other males in various ways. They can mimic females and release sperm instead of eggs in the nest of another male (Gonçalves et al., 1996). Or they can try to sneak copulations with a female, avoiding the costs associated with courtship (Ryan and Causey, 1989). These sneakers can be distinct morphs, but in some species males can switch between roles (Kodric, 1986; Travis and Woodward, 1989). Finally, some males may be satellite males that try to intercept females as they are trying to approach other, courting males (Arak, 1988). This is very common in lek breeding systems, where courters gather and display to choosers. Often this is done in the same place every year.

Males may compete for direct access to females, but they can also compete over resources that will subsequently attract females. This is very prominent in many species of birds where males compete over breeding territories of varying quality, which are in turn evaluated by females.

Sperm competition shows that female choice and male competition can intersect. While male competition can be used to explain why it may be beneficial for males to inseminate females multiple times or with large amounts of semen as a response to the possibility of other males also inseminating the same female, the female may use cryptic female choice to select sperm from a certain male. Because armaments can also be ornaments and traits that are adaptive in fights may also be attractive to females, so female choice and male competition can be intimately intertwined (Berglund et al., 1996).

1.4.4 Female competition

Females often compete with each other over resources, although this can be less obvious as compared with males. Openly aggressive encounters between females are rare, but female competition is probably widespread. However, documentation of female competition over males seems to be relatively rare (Rosvall, 2013; Cain and Rosvall, 2014). There are, however, some studies like the one by Petrie (1983) that clearly shows female competition for males in a lek situation, concluding that “females compete for small fat males.” Most female competition, however, seems to be about resources rather than directly for males (Scharnweber et al., 2011a, 2011b). A field study in a livebearing fish, the Atlantic molly (Heubel and Plath, 2008), pointed toward intensive species competition over males and other resources. This view is supported by recent experimental work on female aggression and competition (Makowicz and Schlupp, 2013, 2015; Makowicz et al., 2016, 2018, 2020) in Amazon mollies (Poecilia formosa), another livebearing fish. This suggests that we need more work on within-species competition, as we seem to know relatively little about within-species female competition. A string of papers has raised important questions about female–female competition and its evolutionary consequences. One especially important aspect here is the distinction between the roles of social selection (Tobias et al., 2012) and sexual selection (Cain and Rosvall, 2014) (Chapter 8). Another important aspect is the potential evolution of armaments and weapons in females. We have some knowledge of this in sex-role reversed species (Watson and Simmons, 2010), but little beyond.

1.5 Definitions

Here I want to provide an operational definition of what “mate choice” is. I am making reference to the definition recently suggested by Rosenthal (2017) and also used by Schlupp (2018): “Mate choice can be defined as any aspect of an animal’s phenotype that leads to it being more likely to engage in sexual activity with certain individuals than with others.”

Note that this definition parts dramatically from the problematic traditional usage of sex roles (AhKing, 2013b). Consequently, Rosenthal (2017) replaces female and male with the terms chooser and courter, which can be of any sex. I agree with this definition, but in this book, I want to retain the usage of male and female as a heuristic tool, to reflect the existing difference in the ecology of early investment into gametes, without acknowledging specific sex roles. Furthermore, I want to emphasize that in my view both sexes can be chooser and courters at the same time. I think that we eventually have to realize that mate choice is best understood as a continuum, with the traditional sex roles of male and female confined to the extreme ends. I propose that in reality in most mating systems, females and males both have preferences, exercise choice, and resolve the underlying sexual conflict with some form of reciprocal mate choice.

Similarly, the term “preference” needs to be defined. Again, I use Rosenthal (2017): “a chooser’s internal representation of courter traits that predisposes it to mate with some phenotypes over others.” The difference between choice and preference is that we can assess choice by measuring actual sexual behaviors and outcomes, while preferences can also be measured indirectly, for example, by using association times or preference functions (Wagner, 1998).

An ornament is a trait (or a combination of traits) that is likely to have arisen via sexual selection and plays a role in mate choice by making the bearer attractive to choosers, often at a cost to survival. Ornaments are often sexually dimorphic, but they do not have to be.

Finally, the terms male and female competition also need to be defined. Broadly speaking these are phenomena where individuals of the same sex compete for access to members of the other sex. This is most obvious in species where individuals of one

sex actually fight with another, but the interactions can be much more subtle.

Both within-sex competition and between-sex choice lead to differential reproduction, which is then exposed to selection.

1.6 Short summary

This chapter is introducing the key topics of the book— male mate choice and female competition—relative to each other, and relative to the very established mechanisms of female choice and male competition. It is important to realize that although male mate choice is common and likely more important than currently realized, it is unlikely to have the same effects on females that female choice has on males.

1.7 Recommended reading

The book by Rosenthal (2017) on mate choice is an excellent and comprehensive account of mate choice.

The short review by Edward and Chapman (2011) captures a lot of the thinking on male mate choice.

Male mate choice in insects is covered by Bonduriansky (2001).

Important historical background is provided by Milam (2010) and Richards (2017).

1.8 Bibliographic information

In February 2018 I conducted a search in the bibliographic database Web of Science to find out how many peer-reviewed scientific papers were published in the areas that are the topic of this book. I first searched very broadly for sexual selection, and then conducted a narrow search for the other terms, male and female choice, as well as female competition and male competition. In Web of Science one has many different options to filter results, but what I did with my search for sexual selection was very simple: I used the core database and typed the terms “Sexual” and “Selection” in the search window in the rubric “Topic.” The time period covered was from 1900 to 2017. This search will find papers in the database that contain the words “Sexual” and “Selection.” This simple search found roughly 27,000 articles. The graph in Figure 1.5 indicates a low number of papers per year until an explosive growth occurs in the field around 1990. This seems to coincide with the publication of Andersson’s formative book (Andersson, 1994), but it is hard to pinpoint a single event that might explain this pattern.

I conducted two much more narrow searches on the core terms relevant to this book. First, I studied female choice. This time I used all available databases in Web of Science but restricted the search to papers

Figure 1.5 Number of papers published per year that contain the words “Sexual Selection.”

1.6 Number of publications per year for the term “Female Choice.”

1.7 Number of

Figure

Figure