NoteonSourcesandTranslations

QuotationsfrommemoirsanddiariesheldattheArchivioDiaristicoNazionale(ADN)arequotedwiththepermissionoftheauthorsortheirfamilies.In caseswhereitwasnotpossibletocontacttheauthorsortheirrelatives,no directcitationsoridentifyingdetailshavebeenincludedbyrequestofthe ADN.Inthesecasesthetextisidentifiedonlyby firstnameandshelfmark.

SeveralofthediariesandmemoirsconservedattheADNweresubsequently published.Inthesecasesitisindicatedthatthepublishedversionoriginatedin atextheldattheADNandthattheyarethusincludedinthesampleset.

AlltranslationsfromItalianaremyownotherwiseindicated.Inmytranslationsfromthediariesandmemoirs,Ihavetriedtokeepascloselyaspossible totheoriginalpunctuationandsyntaxoftheItaliantextinordertobest conveytherhythmsoftheoriginaltextandtorepresenttheauthor’svoiceas accuratelyaspossible.Translationisalwaysanimperfecttaskandnecessarily involvessomemeasureofinterpretation;anyerrorsareofcoursemyown.

Introduction

ThedayofmyweddingeventhoughIseemedhappy.Iwasdespairing thinkingofwhatwasaheadofme.Itwasanobsession.Irememberthat Iwaspreparingthe finaldetailsofthelunch,allalone,whentheyhad alreadyrungthebellsfortheweddingmass[...]Igotdressedinagreat hurrybecauseIwasgoingtobelateotherwise.

EventhoughIverymuchlovedthemanIwasmarrying,tomeitseemed itwasthedayofmyhanging.OnceIarrivedinthechurch,Isaweverythingdouble,Ihadasplittingheadache.Ididn’tsayanythingtoanyone.¹

ThisishowAmaliaMolinelliwroteaboutherweddingattheageof22.Her wordsarestrikinglycandidandevenshockingforawomanwhopresented herselfashappilymarriedinmiddleage.Amaliawasbornin1928toapeasant familyinthenorthernItalianprovinceofEmilia-Romagnaanddescribeda happyruraladolescence,goingtodancesregularlyatweekends.Asayoung womanshehadworkedasadomesticservantinnearbyGenoabutshe dislikedthecity,preferringtheopennessoftherurallandscape.Amalia marriedalocalmanin1950.Astheweddingdrewclose,shewasterrifiedof goingtolivewithherhusband’sfamilyafterthemarriage,aswascustomaryin theruralnorth.Themainemotioninheraccountoftheweddingisfear, althoughitwasonethatshekepthiddenfromeverybodyontheday.Atthe sametime,shewascarefultomentionhowmuchshelovedherhusband,the mantowhomshewouldstaymarriedformorethanthirtyyears.

Despitethebrutallyhonestdescriptionofhowshefeltonherweddingday, Amalia’smemoirwasneverthelessacarefullyconstructednarrativeofherlife. Herchildhoodeducationdidnotgobeyondelementaryschoolaswastypical thenforruralgirls,andshewrotehermemoirbetween1976and1982,after havingreturnedtoeducationtogainhermiddleschooldiploma.Bythistime shewasmarriedforovertwenty-fiveyearsanddescribedherselfasahousewife.Eventhoughthefearandanxietyshefeltonherweddingdaybetraysher

¹AmaliaMolinelli, IpensierivagabondidiAmalia (Milan,2002),p.43.Acopyisalsokeptat theArchivioDiaristicoNazionale(ADN).

deepambivalenceatthatpoint,itseemedinwritinghermemoirthatlovehad tobeapartofthenarrativeofmarriage.In1950,marriageinItalywasstill firmlyseenasalifelongcommitmentandanydebatesaboutdivorcewerefar fromherconsciousnessasayoungwoman.

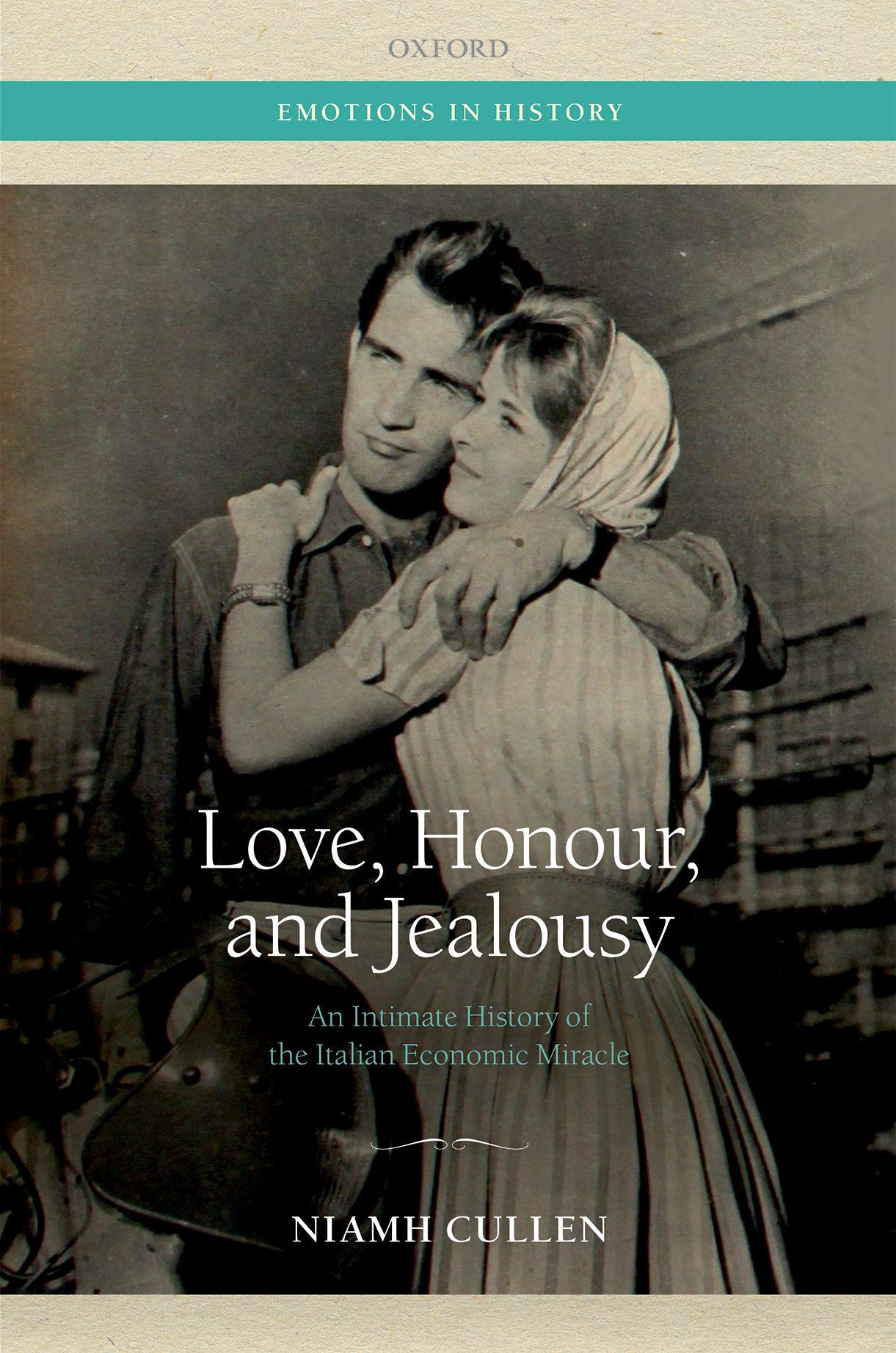

Almosttenyearslater,LiviaColasantiwouldhaveaverydifferentexperienceofromanticpartnership.Bornin1937toamiddle-classfamilyinRome, Livia’schildhoodwasurbanandaffluent.Sherememberedlongperiodsof leisureinherchildhoodwiththefamilyspendingsummersonthebeachat Ostia,justoutsideRome.Herearlyteenageyearswerealsomarkedbytherise ofconsumerismandpopularculture;particularlyfashionandmusic.At15she beganwork,whilealsotakingasecretarialcourseatnightandstartingwhat shedescribedasagood,solidjobattheageof21.Shehadmetherpartner Dariothepreviousyearin1957.Hewasmarried,althoughseparated.In1964 LiviabecamepregnantandwenttolivewithDario.Althoughherimmediate familyacceptedthesituation,aweddingreceptionwasheldinordertosave faceinfrontoftheextendedfamily,withthe fictionthataprivateceremony hadtakenplacebeforehand.The ‘farce’ involvedafullreceptioninabarfacing theTiber,andahoneymooninFlorence.Uneasyrecallingitevenmanyyears laterinhermemoir,Liviacomparedthestagedweddingto ‘acomedy,a scenariofroma1950s film’,andlikenedherselfandDariotothecoupleina posedpublicityphotographofabrideandgroominStPeter’sSquare.The growingmediafocusonmarriageandromanticlovein film,music,and advertisingevidentbythe1960swas,inherview,atoddswiththerealityof hersituation.

SheleftDarioninemonthsafterherdaughterwasborn.Sheasked ‘how couldIhavelivedwithamanwhowasunfaithful,whodidnotsharemy politicsandwhoevenmockedmyviews[ ...]?’.²InLivia’smemoir,thenotion ofromanticloveprovidedameasureagainstwhichherownrelationshipwas testedandfailed,unlikeinAmalia’snarrativewherelovewaspresentedasa seamlessandbarelyexaminedcomponentofthemarriage.Thecommercializationofromanticloveonlyhighlightedthediscordanceofthestaged weddingofLiviaandDario.Livia’smemoircontainedamuchclearernotion ofwhatanidealromanticpartnershipwouldinclude,andshewascertainthat herownexperiencewithDariodidnotliveuptoherideals.Thedifferences betweenAmalia’sandLivia’sattitudestowardsmarriageandloveareasharp illustrationofanItalyintransformation,notjustinmaterialcircumstances butinattitudes,expectations,andfeelings.Althoughbothwomenwrotetheir memoirsinmiddleage,theirattitudeswereclearlyshapedbytheworldin whichtheycameofage.InAmalia’scasethiswastheruralnorthwherethe needsoffamilywereplacedaboveallelse,whilein1960sRome,Liviacould

²LiviaColasanti,

‘Ilsaporedellacioccolata’,MP/10,ADN.

haveajobandenjoyfashion,popularmusic,and film.Crucially,thetwo womendifferednotjustintheirexperiencesbutinhowtheymadesenseof theirlivesandtheirfutures.UnlikeAmalia,Liviawasabletoimaginethather lifecouldbedifferent.

Thisbookwillexplorethestorynotjustofhowpracticesofcourtshipand marriagechangedinItalybetween1945and1974,buthowitbecamepossible forItalianmenandwomentothinkabouttheirlives,emotions,andtheir choicesdifferently.Itwilldosobydrawingcloselyonalargebodyofmostly memoirsanddiaries,setagainstthecontextofthepopularculturethatthese menandwomenabsorbedintheiryouthandyoungadulthood.Initsfocus ontheordinarylivesofItalians,thisbookaimstowriteasocialhistoryof emotionsduringItaly’seconomicmiracle.Indoingsoitpaysanimportant debttothegrowingnumberofhistoriansinvestigatingthemodernhistory oflove,courtship,andmarriage,includingClaireLanghamer,SimonSzreter, andKateFisheronEngland,DagmarHerzogonsexualityinEurope,Hester Vaizey,PaulBetts,andJosieMcLellanonmodernGermany,andRebecca PuljuandSarahFishmanonFrance.³Emotionshavealsobeencommanding attentioninmodernItalianhistory,notablywiththeworkofMarkSeymour andPennyMorris.⁴ MeanwhiletheworkofAnnaTonelliandMariaPorzioon thepoliticsofloveandsexualityandofEnricaAsqueronmiddle-classlife duringtheeconomicboom,makevaluablecontributionstothehistoryof

³ClaireLanghamer, TheEnglishinLove:TheIntimateStoryofanEmotionalRevolution (Oxford,2013);SimonSzreterandKateFisher, SexBeforetheSexualRevolution:IntimateLifein England1918–1973 (Cambridge,2010);DagmarHerzog, SexualityinEurope:ATwentieth CenturyHistory (Cambridge,2011);HesterVaizey, SurvivingHitler’sWar:FamilyLifein Germany,1939–1948 (London,2010);JosieMcLellan, LoveintheTimeofCommunism: IntimacyandSexualityintheGDR (Cambridge,2011);PaulBetts, WithinWalls:PrivateLife intheGermanDemocraticRepublic (Oxford,2010);RebeccaPulju, ‘FindingaGrandAmourin MarriageinPostwarFrance’,inKristinCelelloandHananKholoussy(eds), DomesticTensions, NationalAnxieties:GlobalPerspectivesonModernMarriageCrises (Oxford,2015);andSarah Fishman, FromVichytotheSexualRevolution:GenderandFamilyLifeinPostwarFrance (Oxford,2017),pp.126–46.Otherworksspecificallyonthehistoryofromanticlovetakea moreculturalandintellectualperspective:seeWilliamReddy, TheMakingofRomanticLove: LongingandSexualityinEurope,SouthAsiaandJapan,900– 1200 CE (Chicago,2012)and LuisaPasserini, WomenandMeninLove:EuropeanIdentitiesintheTwentiethCentury (NewYork,2009).

⁴ SeePennyMorris, ‘AWindowonthePrivateSphere:AdviceColumns,Marriageandthe EvolvingFamilyin1950sItaly’ , TheItalianist,27:2(2007),pp.304–32and ‘Feminismand Emotion:LoveandtheCoupleintheMagazineEffe’ , ItalianStudies,68:3(2013),pp.378–98; MarkSeymour, ‘EpistolaryEmotions:ExploringAmorousHinterlandsin1870sSouthernItaly’ , SocialHistory,35:2(2010)pp.148–64and ‘EmotionalArenas:fromProvincialCircusto NationalCourtroominLateNineteenth-centuryItaly’ , RethinkingHistory,16:2(2012), pp.177–97.SeealsoMartynLyons, ‘“Questocorchetuosirese”:ThePrivateandthePublic inItalianWomen’sLoveLettersintheLongNineteenthCentury’ , ModernItaly,19:4(2014), pp.355–68andPennyMorris,FrancescoRicatti,andMarkSeymour(eds), ModernItaly: Special IssueontheEmotions,17:2(2012),pp.151–285.

sexualityandintimatelife.⁵ Thisbookbuildsonthiswork,andthroughitsuse of first-personwriting,providesnewandoriginalinsightsintothesocial historyoflove,sexuality,andmarriagewithimplicationsnotjustforItaly butmorebroadlyforEuropeinthesameperiod.

FROMPOST-WARRUINTOPROSPERITY: THEITALIANECONOMICMIRACLE

ThecontrastbetweentheperspectivesofAmaliaandLiviaonloveand marriageillustratetheextentofItaly’stransformationinthedecadesfollowing thewar.Apeasantwomanmarryingin1950andamiddle-classwomanin 1960sRome,thetwowomenaredividedbyplaceandclassbutalsobytime. Italyintheearly1950swasstilllargelyapoorandruralsociety,recently ravagedbywar,sociallyconservative,anddeeplydivided.Evenasthenew ItalianRepublicsoughttodistanceitselffromtherecentpast,thememoryof fascismandthetraumaofwarwerestillpresentinmanyminds.Themenand womenatthecentreofthisbook,comingtoadulthoodinthepost-warperiod, hadmostlyexperiencedfascismaschildrenandsomeasadolescents.Fewof themenhadbeenoldenoughto fightinthewar,buttheywouldlikelyhave participatedinfascistyouthorganizationswheretheyimbibedthemessage ofmartialmasculinity,justasgirlsreceivedmessagesaboutfascistmotherhood:traditional,submissive,andprolific.⁶ Thereactionarygenderpoliticsof fascismultimatelyhadlittledemographicimpactalthoughitisaltogether moredifficulttogaugetheimpressionthesemessagesmadeonyoungItalians.

TheretrenchedpositionoftheCatholicChurchcombinedwithColdWar politicstomakepost-warItalyasocietythatwasbothconservativeanddeeply divided.⁷ Asalegacyoftheantifascistresistance,ItalyhadthelargestCommunistParty(PartitoComunistaItaliano,orPCI)inWesternEuropeafter 1945,creatingtwostrongopposingideologieswithdeeprootsinsociety. CommunismandCatholicismwerenotjustaboutpoliticsandreligion;each

⁵ MariaPorzio, Arrivaniglialleati!Amorieviolenzenell’Italialiberata (Rome,2011);Anna Tonelli, Gliirregolari:AmoricomunistialtempodellaGuerraFredda (Rome,2014);Enrica Asquer, Storiaintimadeicetimedi:Unacapitaleeunaperiferianell’Italiadelmiracoloeconomico (Rome,2011).

⁶ Theliteratureongenderandfascismisextensive.SeeespeciallySandroBellassai, ‘The MasculineMystique:AntimodernismandVirilityinFascistItaly’ , JournalofModernItalian Studies,10(2005),pp.314–35;PaulGinsborg, FamilyPolitics:DomesticLife,Devastationand Survival1900–1950 (NewHaven,CT,2014),pp.139–225;VictoriaDeGrazia, HowFascism RuledWomen (Berkeley,CA,2000);andNatashaChang, ShapingtheNewWoman:BodyPolitics andtheNewWomaninFascistItaly (Toronto,2015).

⁷ SeePaulGinsborg, AHistoryofContemporaryItaly,1943–1980 (London,1990).

onewasalsoawayoflife,withsociallifebeingorganizedaroundthepartyfor PCImembersandmanymillionsofItaliansbelongingtoCatholicActionand otherCatholicandyouthorganizations.⁸ TheCatholicChurchofthe1950s continuedto fightthebattleagainstbothcommunismandmodernityby focusingongenderandsexuality,andtheprincipaltargetwasthepurityof girlsandyoungwomen.⁹ Catholicismwasespeciallystronginthenorthand north-eastofItaly,whileinthesouthlocaltraditionalsocontributedtoa socialandculturalclimatethatwasdeeplyconservativeinitsattitudestowards women.ThePCI,stronginthenorthandcentralregions,didlittleinpractice tochangedeeplyentrenchedideasaboutgenderroles.¹⁰ Inasocietythatwas stillpredominantlyrural,thestrongestinfluenceremainedthatofthefamily. InthesouthofItaly,inSicilyandCalabriainparticular,thenotionoffamily honouralsoplayedanimportantpartintheregulationofwomen’slives. Theseattitudesandcustomsledinextremecasestocrimesofhonour,which wereregularlyinthenews,andforcedmarriageswhich,withtheexceptionof the1965caseofFrancaViola,tendedtoremainprivatematters.

Bythelate1950sandearly1960s,averydifferentItalywasbeginningto emerge.The ‘economicmiracle’ oftheindustrialnorthbegantotakeoffinthe late1950s,sparkingwidespreadmigrationtoMilan,Turin,andGenoaand moregenerallyfromruraltourbanItaly.Itisestimatedthatatleastninemillion anduptotwenty-fivemillionItalians(roughlyhalftheentirepopulation)were onthemoveintheseyears.¹¹Notallofthesemovedfarenoughtobeproperly consideredmigrants,butitisalsocertainthattherealnumberofinternal migrantswasfarabovetheofficial figuresfortheseyears.Thisunprecedented waveofmigration,predominantlyfromruraltourbanItaly,undoubtedly changedItaliansociety.TheriseofprosperityandconsumerculturetransformedtheordinarylivesofmillionsofItaliansbothinmaterialtermsandin

⁸ SeeDavidForgacsandStephenGundle, MassCultureandItalianSocietyfromFascismtothe ColdWar (Bloomington,IN,2007),pp.247–68;SandroBellasai, Lamoralecomunista:Pubblicoe privatonellarappresentazionedelPci(1947–1956) (Rome,2001);andDavidKertzer, Comrades andChristians.ReligionandPoliticalStruggleinCommunistItaly (Cambridge,1980).

⁹ PercyAllum, ‘UniformityUndone:AspectsofCatholicCultureinPost-warItaly’,in ZygmuntBaranskiandRobertLumley(eds), CultureandConflictinpost-warItaly:Essayson MassandPopularCulture,(London,1990);PatrickMcCarthy, ‘TheChurchinPostWarItaly’,in PatrickMcCarthy(ed.), Italysince1945 (Oxford,2000).

¹⁰ MariaCasalini, Famigliecomuniste:Ideologieevitaquotidiananell’Italiadeglianni ’50 (Bologna,2010).

¹¹Ginsborgreportsthe figureofjustoverninemillionforintra-regionalmigrationbetween 1955and1971whileCrainzreportsa figureofapproximatelytenmillionforintra-regional migration: AHistoryofContemporaryItaly,p.219;GuidoCrainz, Storiadelmiracoloeconomico: Culture,identità,trasformazioni (Rome,2005),p.108.Thedisparitiesandthelackofprecise figurescanbeexplainedbythefactthata1939lawdesignedtolimitmigrationfromrural areas onlyrepealedin1961 madeitverydifficultformigrantstoestablishlegalresidencyin theirnewtownorcity.SeealsoStefanoGallo, Senzaattraversarelefrontiere:Lemigrazioni internedall’Unitàaoggi (Rome,2012).

theirvalues.¹²Theriseofmassculture,fromcinemaandpopularillustrated magazinesintheearly1950stotelevisioninthelate1950sand1960s,also transformedidentitiesandperspectivesfromlocaltonationalandtransnational.TheinfluenceoffamilyandreligiononyoungItalianswasgivingwayto modernsecularvalues,whilethepopularizationofthenotionof ‘companionate marriage’ andthegrowingcommercializationofromanticloveinItalyas elsewheretransformedexpectationsofmarriageandincreasinglyplacedthe burdenofchoiceonindividualsratherthanontheirfamilies.Theopportunities affordedtowomenwerechangingtoo,andnewideasaboutgenderinfluenced attitudestowardscourtshipandmarriage.Ofcourse,theseprocesseswerenot assimpleoraslinearasthisnarrativemightsuggest,andthisbookwillexplore thosecomplexities.

Thoseborninthe1940sandcomingofageinthemidtolate1960s inheritedaverydifferentworldtothosebornduringthepreviousdecade. Althoughtheymighthave(barely)livedthroughthewaraschildren,theirs wasanItalywhichquicklyleftbehindtheausterityandconservatismofthe early1950sforItaly’ s ‘miraculous’ 1960s.Thisgenerationwaslikelytoreceive abettereducationthanpreviousgenerations,withthenumbersattending secondaryschoolanduniversityexpandingrapidlyintheseyears.¹³Bythelate 1960s,manyofthisgenerationalsobegantorejecttheconsumerismofthe boomyears,andthesocialconformismitfostered,dismissivelysummarized asthe ‘threeMs’ : ‘macchina,moglieemestiere’ (car,wife,andprofession).¹⁴ In rejectingtheconsumerismoftheboomyears,somealsorejectedtheconventionalmodelofmarriageandfamily,experimentingwithnewformsoflove andcommitment.WhiletheItalian ’68isnotcentraltothestoryofthisbook, severalofthemenandwomendiscussedherewereinvolvedinthewider movementandhadtheirexperiencesofloveandsexualityshapedbythe cultureofthoseyears.TheItalianfeministmovementwhichgrewoutof ’68 wasalsocrucialtothelivesofsomeofthewomen,transformingtheirattitudes tomarriageandfamily,withseveralwomenevencomingto1970sfeminismin laterlifeasmarriedwomen.Inthesecasestheencounterwasoftenacatalyst forchange,althoughmostmemoirsdescribedagradualshiftinoutlookrather thanasuddentransformation.

Inamoregeneralsense,thisbookaimstotellthestorynotofactivistsorof thosecentraltothecountercultureofthelate1960sandthesocialmovements ofthe1970sbutratherofthoseattheperiphery.Wewillseehowtheordinary

¹²EmanuelaScarpellini, MaterialNation:AConsumer’sHistoryofItaly (Oxford,2011), pp.109–224;SimonettaPicconeStella, Laprimagenerazione:Ragazzeeragazzidelmiracolo economicoitaliano (Turin,1993).

¹³RobertLumley, StatesofEmergency:CulturesofRevoltinItalyfrom1968to1978 (London, 1990);AnnaTonelli, Comizid’amore:Politicaesentimentidal ‘68aiPapaboys (Rome,2007); AnnaBravo, Acolpidicuore:Storiedelsessantotto (Rome,2008).

¹⁴ GuidoCrainz, Storiadelmiracoloitaliano,p.143.

livesexaminedinthisbookrevealadifferent1960stothenarrativeof liberalizationthatemergesinpopularcultureandthroughasingularfocus on ’68.Indeedtheintentionofthisbookistocomplicateandtochallengethis narrative.Itisnotjust,aswewillsee,thatexpectationsdidnotalwaysmatch realityandthatdevelopmentwasuneven,aswasthecaseparticularlyinrural Italyandinthesouth.Wemustalsotakeaccountthat,aswithjealousy,change didnotalwaysmoveinastraightforward,liberaldirection.Moreover,itis worthnotingthatnotallexperiencesareaddressedinthebook.Theabsence ofhomosexualityisareflectionofthestrongheteronormativityofthesources, whetherthosedrawnfromthemediaandpopularcultureorthepersonal texts.Differentsourceswouldhavebeenneededtouncoverthesehidden experiences;whatweseeinthediariesandmemoirshereexaminedarethe attemptsthatordinarypeoplemadetoplacethemselvesandtheirexperiences inrelationtodominantdiscoursesratherthan(forthemostpart)indefiance ofthem.¹⁵ Wecanonlyspeculateaboutwhatstoriesmightbefurtherhidden. Letusnowturntothepersonalnarrativesthataresocentraltothisnewstory ofpost-warItaliansociety.

FIRST-PERSONWRITING:THENARRATORS

Asamplesetof142 first-persontextsareusedinthisbook,alldrawnfromthe textscollectedinItaly’sNationalDiaryArchive,locatedinPieveSantoStefano inTuscany.Whilethemajorityofthetextsarememoirs,somearediaries(most ofthesewereadolescentdiariesdetailingschoolanduniversitylife,although theyincludeonebyawomanofficeworkerandonebyamalemigrantworker in1950sGermany).Thecriteriaforinclusioninthesamplesetwerebroadly defined:allwritersbornbetween1926and1946(andthusgrowingup andcomingofageinthe1950sand1960s)andwhereatleastsomedetailof eitherlove,sexuality,courtship,ormarriagewereincluded.Thisamountedto fifty-ninetextsbymenandeighty-threebywomen.Thetextsvarygreatlyin lengthandstyle,andinthelevelofdetailtheyprovide.Somehavebeenused extensively,analysedintermsoflanguageandstructureaswellascontent, whileotherssimplyconfirmedpatternsandtrends.Althoughthesampleset

¹⁵ ScholarshaverecentlydevotedmuchattentiontouncoveringthehistoryofItalianhomosexualityinthelatenineteenthandearlytwentiethcenturies,althoughmoreneedstobedonefor thelatetwentiethcentury.TheseworksincludeChiaraBeccalosi, ‘TheOriginofItalianSexologicalStudies:FemaleSexualInversion c. 1870–1900’ , JournaloftheHistoryofSexuality,18:1 (2009),pp.103–20;LorenzoBenadusi, TheEnemyoftheNewMan:HomosexualityinFascist Italy (Wisconsin,2012);CharlotteRoss, EccentricityandSameness:DiscoursesonLesbianism andDesireBetweenWomeninItaly, 1960sto1930s (Oxford,2015);andValeriaBabini,Chiara Beccalosi,andLucyRiall(eds), ItalianSexualitiesUncovered,1789–1914 (London,2015).

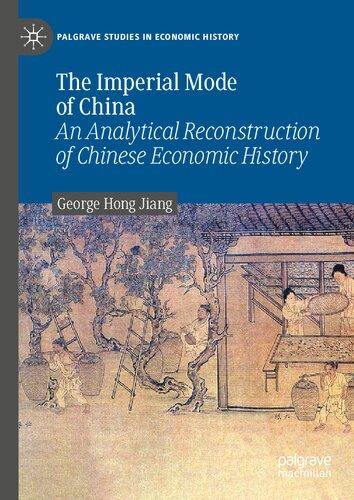

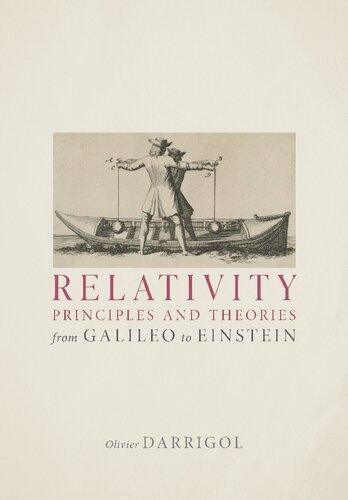

happenstohaveaslightlyhigherrepresentationofwomenthanmen,thatis nottosuggestthatmendidnotconsiderlove,courtship,andsexualityimportanttotheirlives.Manyofthemenconsideredinthesepagesactuallywrotein hugedetailandwithgreatintensityabouttheseaspectsoftheirlives.Atthe sametime,menwerealsomorelikelytowriteadiaryormemoirofwork, career,orpolitics,compartmentalizingtheirexperiencesofintimacyorfamily. Intermsofgeographicalspread,thetwentyItalianregionswerefairlyequally represented(seeFigureI.1).Themalewriterswereveryevenlyspreadacross Italy,withtwenty-twofromnorthernItaly,twentyfromthecentralregions, andtwentyfromthesouth,includingSicilyandSardinia.Thewomenwere

FigureI.1. MapofItaly,showingtheregionalprovenanceofthediaristsandmemoiristsasperAppendix1. <http://www.geocurrents.info/cartography/customizable-base-maps-of-italy>.

Sardegna

Sicilia

Calabria

Puglia

Basilicata

Campania Molise

Abruzzo Lazio

Umbria Marche

LombardiaVeneto

TrentinoAlto Adige Friulivenezia Giulia

Toscana

Liguria Emilia-Romagna

Piemonte Valle d'Aosta

morelikelytobefromnorthernItaly(thirty-nine),withtwentycoming fromcentralItalyandtwenty-threefromthesouth.Urban,provincial,and ruralbackgroundswerealsoallstronglyrepresented.Theculturalpositionof womeninthesouthofItaly,whichoftenmeantamoresecludedlifeand lowerlevelsofeducationandparticipationintheworkforce,mayexplainthe lowernumberofsouthernwomenwritersaswellastherelativesilenceon certaintopics.¹⁶

Classisdifficulttogaugepreciselyfromthetexts.Thediaristsareoverwhelminglymiddleandupperclass,whilethebackgroundsofthememoirists aremuchmorediverse.Althoughlessthanhalfoftheauthorsgavedefinite informationontheirclassorfamilybackground,thepartialinformationgiven suggeststhatclassisfairlyevenlyrepresented(seeAppendix1).Atleasteleven menandsixteenwomenmemoiristscamefrompeasantbackgrounds,while theregionswerealsofairlyevenlyrepresentedintheruralmemoirs.¹⁷ AlthoughthemajorityoftheItalianpopulationwasruraluntiltheonsetof theeconomicmiracle,theexperiencesofpeasantsaredifficultforhistoriansto access,beyondregionallyspecificworkssuchasNutoRevelli’sextremely valuableoralhistoriesofPiedmont.¹⁸ Thesetextsthusrepresenttheenormous valueoftheNationalDiaryArchive.¹⁹ ThestrongrepresentationofworkingclassandpeasantmemoiristscanperhapsbeexplainedbytheItaliantradition ofpopulartestimony,whichwaslinkedtopost-warleft-wingpoliticaltraditionsandcultivatedinparticularbytheDiaryArchive.

Thewritersweremorelikelytodisclosetheirowneducationalachievement thantheirfamilybackground,andonthesubjectofeducationweseeastrong genderdisparity(seeAppendix2).Althoughthetypicalpatternforpeasant familiesuptothe1950swasforboystoattendschooluntil10or11,themale memoiristsfrompeasantbackgroundswereoftenatypicalinthattheyhad completedmiddleschoolorgoneontofurthereducation.²⁰ Veryfewofthem

¹⁶ SeePerryWillson, WomeninTwentiethCenturyItaly (London,2009),pp.71–3and 117–18andSimonettaPicconeStella, Ragazzedelsud:Famiglie, figlie,studentesseinunacittà meridionale (Rome,1979).

¹⁷ Ofthetenmenfrompeasantbackgrounds,onewasfromnorthernItaly,fourfromthe south(includingSicilyandSardinia),and fivefromthecentralprovinces.Thewomenwere spreadmoreevenly: fivewerefromnorthernItaly,fourfromthesouth,andsixfrom centralItaly.

¹

⁸ NutoRevelli, Ilmondodeivinti:Testimonianzedivitacontadina (Turin,1977)andNuto Revelli, L’anelloforte.Ladonna:storiedivitacontadina (Turin,1985).

¹⁹ Peasantor ‘contadino’ isgenerallyusedtorefertobothsmallfarmersandlandlessrural labourersinItaly.RudolphM.Bellstatesthatheusestheterm ‘torefertoallagriculturalmanual labourercategoriesnotedabove(smallholders,landlessandambiguous)andspecificallyto excludesubstantiallandholdersandagriculturalcapitalistsandmiddlemen’.Quotedin ‘“What isaPeasant?”’,inRudolphM.Bell, Fate,Honor,FamilyandVillage:DemographicandCultural ChangeinRuralItalySince1800 (Chicago,1979).

²⁰ Compulsorysecondaryschooleducationuntiltheageof14wasonlymadelegalin1962: seeGinsborg, AHistoryofContemporaryItaly,p.298.