Acknowledgments

This project began at the University of Illinois, where my mentor, Peter Fritzsche, directed me to Berlin’s daily newspapers as the best source for turn-of-the-century urban life in Berlin. Peter then wisely counseled me to embed my burgeoning interest in the newspaper personal ads I found there in a larger investigation of love in the big city of Berlin, and I am thankful to him for his expert guidance in storytelling and historical analysis at every step along the way. Peter taught me that history is, at heart, about telling beautiful stories, and this advice has stuck with me perhaps more than anything else I have learned about being a historian.

I had the support of the entire history department throughout my time at Illinois, and immense thanks are due also to Mark Micale, Harry Liebersohn, and Mark Steinberg, who, together, made up my dissertation committee and made that initial project so much better. They recognized that I had first written a book, not a dissertation, and prefaced their requests for more dissertation-like theoretical and methodological content with the advice that I should save a copy of my manuscript, make the necessary additions to a separate document to use as the dissertation, and then return to the former. This book is so much more than that saved file, but they were absolutely right, and I am grateful to them for their friendship and training over the years.

In a (now) somewhat more distant but no less important way, I would also like to thank my academic mentors from graduate school and college, notably Clint Shaffer, who took me to Germany for the first time and inspired me to study German; Dean Rapp, from whom I took my first (and still favorite) history course; Rainer Nicolaysen and my cohort at Middlebury College, where I sharpened my German-language abilities; Suzanne Kaufman, David Dennis, and Timothy Gilfoyle, who gave me my first professional historical training; and Ute Frevert, who served as my adviser-away-from-home in Berlin and welcomed me into the fold at her fascinating History of Emotions institute.

Acknowledgments

For that matter, I first learned German from Margy Winkler and Heidi Galer at Iowa City West High School, and I do not see how I would have even come to this project in the first place without their excellent teaching and inspiration.

Numerous institutions and archives were critical to the development of this book, notably the Fulbright Commission, which funded a year of research in Berlin; the German Historical Institute, without whose training in reading the old German script I would have floundered in many of the archives I visited; and the Iowa City Noon Rotary Club and Doris G. Quinn Foundation, both of which provided important funding throughout the research and writing process. Archivists in Germany—especially the staff at the Landesarchiv Berlin, the Zentral- und Landesbibliothek Berlin, and the Deutsches Tagebucharchiv in Emmendingen—were also ever helpful and friendly to me as I came and went each day and made the research experience a degree less lonely and isolating.

Special thanks are due to Cornell College, where I teach and have been welcomed warmly by my colleagues in both History and Modern and Classical Languages, not to mention the entire college. The very first course I taught at Cornell was an upper-level German seminar on the history of Berlin, and that first class of five students was treated to some early material from this book. From the very beginning, then, my students have been wonderful and insightful interlocutors on the many themes and topics that make up this book.

I am thankful also to my editor, Susan Ferber, for taking such a keen interest in this book and shepherding it through to its completion, as well as to the anonymous reviewers of the manuscript, whose comments and critiques without question made this book better. My friend Suja Thomas also deserves many thanks for her creative ideas, advice, and friendship along the publishing road.

My gratitude to my family extends well beyond this book, but they of course helped in a variety of ways on this project, too. My father-in-law used countless frequent flyer miles to cover flights back and forth from Berlin so I could visit my wife back in Iowa during my year of research. My motherin-law, too, provided critical support for us throughout the process. And my wife’s great aunt, Dorothee, who lived in Munich until her death in 2014 at the age of ninety-three, was a dear friend and incisive historical interlocutor. My visits to her nursing home were always filled with much laughter and discussion about Germany, past and present, and I am sad that she is not here to see the finished product.

Acknowledgments

My mom and dad, brother and sister, grandparents, and wonderful in-laws have been enthusiastic supporters of this book project and were always eager to celebrate each milestone along the way. Special thanks are due to my mom and dad, who, among many, many other things, provided a most idyllic and nurturing upbringing and set me on a path for success and, more importantly, happiness. My siblings and their families have made every step along the way fun and memorable, and I am so very thankful to my grandpa and grandma for their innumerable kindnesses over the years.

This book is a history of love and dating, and it is dedicated to my own two loves: my wife, Melissa, and our daughter, Lena. Though she was not in Berlin with me when I made my archival discoveries, Melissa was the first to learn about each find, first to hear my ideas for weaving this story together, and always full of outstanding ideas for making it better. She has read, edited, and praised every part of this book, and it is infinitely better for it. And I am infinitely better because of her.

As for my daughter, I was editing portions of this manuscript as a weekold Lena lay sleeping in my arms, and I was sublimely happy. Lena will be just under a year old when the first copies of this book are printed, and while she is not yet old enough to read it, I hope and trust she will be proud of her dad when she is.

Love at Last Sight

Introduction

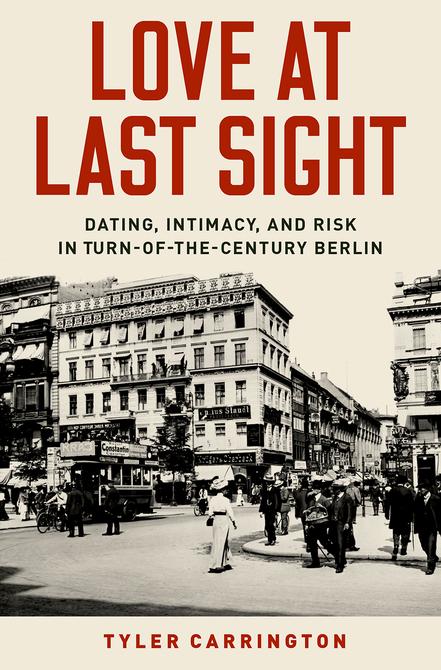

On June 17, 1914, a thirty-nine-year-old, single seamstress named Frieda Kliem left Berlin on a suburban commuter train to meet the man she had fallen in love with through a newspaper personal ad. What she found when she got there was not the wedding proposal she had hoped for or even the man she thought she knew. The man she met murdered her, stole her keys, and made off with the few valuables she had in her tiny Berlin apartment. When a forester found her body over a week later, the police launched an investigation into her upbringing, adult years, and love life that later made up the core of a highly publicized murder trial during World War I, one that pitted the full legal resources of the state against Berlin’s most famous defense attorney, featured delays, false starts, and lengthy recesses, and produced more than one shocking twist. After the jury’s verdict rang out in 1916, the case documents were placed back in their file folders, the evidence was sealed in green police envelopes, and the entire stack was filed away in the police archives, where it sat unused and unopened for the rest of the twentieth century.

On August 22, 2011, while searching through Berlin’s state archive for material related to love at the turn of the century, I came across these files, the first of which detailed the police’s frantic search for Frieda Kliem’s murderer. As I worked my way through the file, opening green police envelopes of sealed evidence and hoping the archivists would not mind that I was ripping into previously unopened, century-old materials, I began to piece together the fascinating story of a poor, single Berlin seamstress who spent her life searching for love in the modern metropolis but found each effort to make connections and find intimacy thwarted. Here was a woman who, like hundreds of thousands of others, had arrived in Berlin at the moment of its metamorphosis into the most dynamic city in the world and then struggled to make her way without much in terms of family connections, employment

prospects, or, crucially, money. It soon became clear that while Frieda Kliem was, paradoxically, totally unknown and, for a few weeks during 1914–1916, a sensation about whom every Berliner was talking, she was also the consummate turn-of-the-century Berliner. Apart from the fact that she was violently murdered, her concerns, her joys, and her everyday existence were shared by thousands upon thousands of other similarly ordinary Berliners whose lives were unremarkable enough that they have all but been forgotten.1

Love at Last Sight is about Frieda Kliem’s world—more specifically, about the in-between people and places that held it all together. The turn- ofthe- century city, indeed, the modern world it typified, was filled with the aspirations and anxieties of people like Frieda, people who were in a perpetual state of becoming.2 For Frieda, as for so many Berliners at the time, “becoming” was all about becoming middle class, which stood above all for financial stability but also encompassed a set of social and cultural markers that conferred status and respectability. Frieda moved in and out of the middle class, but she spent most of her time somewhere between the working class and the lower middle class. Indeed, while her upbringing in a relatively prosperous rural family imbued her with some of the pretentions of the middle class, her independent spirit, her move to the big city of Berlin, and no doubt her gender seemed to set her back perpetually and leave her on the boundary of middle- classness, ever striving for a stable rung on which to plant her foot and move up the social ladder.

The historical questions Frieda Kliem’s life raises are not new. Scholars have long sought to shed light on the complexities of class belonging and striving, on the tensions of urban life, and on the way intangible desires and emotions render each of these still more complicated and fraught. Yet employing Frieda as a prism for these topics—and focusing on love, intimacy, and dating— fractures many of the established ways of thinking about the city, the middle class, and modernity itself, and it reveals the mix of excitement and risk of trying to piece together modern love and middle-class respectability.

At the center of this book is the middle class, or at least the dream of being middle class. Working- and lower-middle-class Berliners like Frieda were keenly aware of their city’s hegemonic middle-class moral and cultural norms, and practically all men and women of these classes harbored not only the desire to achieve and adopt middle-classness for their own lives, but also the sense that it was possible and achievable, whether through hard work,

craftiness, or sheer luck.3 Bürgerlichkeit, or middle-classness, thus in many ways extended beyond the very boundaries it defined and defended, and focusing on the margins of middle-classness opens a window onto the turn-ofthe-century urban world.

But why was middle-classness so central to the way Berliners ordered their lives? Surely there was a degree of comfort associated with middle-class life. It was a cut above the gritty, tedious existence of peasants and workers. It also lacked the heavy baggage of the deeply patinated upper class. The middle class was in fact relatively new, the creation of the industrial age, and perhaps its newness made it seem a degree more attainable. But by the end of the nineteenth century, the middle class was confronting a threat it perceived in the social, cultural, and political aspirations of a rising working class.4 Fearing that its borders were becoming more porous, the middle class sought to immure itself by re-emphasizing the pristine moral, social, and heavily gendered qualities required to belong in its ranks.

But it had little to worry about, for the walls of the middle-class fortress were solid. Strict norms of respectable comportment ensured internal cohesion, and children of middle-class parents were generally careful to marry other middle-class men and women.5 Middle-class people were mostly uninterested in aping the styles of the upper class, and middle-classness, based as it was on this contentedness, in this way contained its own raison d’être.6 Theodor Mommsen put it succinctly in his 1899 diary with the aphorism, “[Ich] wünschte ein Bürger zu sein” (“If only I were middle class”). Mommsen’s famous line may contain an underlying pessimism, but the self-legitimacy and desirability of middle-class status at the turn of the century is unmistakable.7 Indeed, middle-classness became at the end of the nineteenth century a sort of “religious mood” with its own sacralized tenets and values.8 Middle-classness, despite the usual handwringing, was thus still quite hegemonic, quite safe at the turn of the century.

If there were any cracks in the foundation, they were in the modern city and in the private and intimate aspects of men’s and women’s lives.9 The modern city and its manifold new lifestyle opportunities offered a chance at individualism and the cultivation of the modern self. But there was an inherent unorthodoxy to the modern self, and this created immense tensions for men and women on the margins of the middle class. As they moved from provincial towns to modern metropolises like Berlin, and as middle-class life became ever more fixed to urban centers, they were confronted with this tension between the opportunities for modern self-creation and the risk of losing the status and respectability of middle-classness.10 Sociologist Ulrich Beck

calls this the tension of “individualization” in the modernized world. When the conditions of a more traditional, communal society melt away—as in the turn-of-the-century city—the individual becomes free to make her own way, free to forge her own self based on the opportunities of modern metropolitan life. But she also has no choice but to do so, and this produces tremendous anxiety.11 In turn-of-the-century Berlin, men and women on the margins of the middle class also had to do this on their own, for the middle class lacked the solidarity of the working class and the built-in securities of the upper class. The risks of individualization were present in all aspects of life—work, leisure, dress—but especially so in intimate, private life.12 As Beck writes, the private sphere was not immune to this modern conundrum; in fact, the tensions and anxieties of individualization were intensified in intimate matters, for here “the outside [was] turned inside and made private.”13 Love, marriage, and family, in other words, were in many ways thus the locus of this central tension of modern, urban, middle-class life.

This book approaches middle-classness in turn-of-the-century Berlin through the lens of love, marriage, dating, and intimate relationships because searching for and articulating love—indeed, navigating its compulsions, risks, and tensions—revealed the most foundational values of modern urban life.14

Contemporary observers noticed as much: the pioneering sociologist Georg Simmel considered love “one of the great formative categories of existence,” while Marianne Weber, another giant of sociology, recognized love as central to “matur[ing] to human wholeness.”15 Not everyone could speak so eloquently, but the changing dynamics of love and intimacy at the turn of the century nevertheless had people talking about them as never before.16

The modern metropolis presented men and women with the tools, ideas, and dreams for a different approach to love, intimacy, dating, and marriage. But it was not really the newness of these emerging approaches to love, nor frustrated marital dynamics, that occasioned so much talk and debate.17 The debate was so fierce, rather, because love (and gender and sexuality, more generally) at the turn of the century was the site of a battle between a conservative middle-class orthodoxy and the bewildering and tantalizing explosion of new possibilities in the modern metropolis.18 It was the thrilling but clearly transgressive possibility of women proposing to men, of meeting on the streetcar or through the newspapers, indeed, of marrying outside of the social circle deemed acceptable by family and friends. These were plainly off-limits for middle-class people, but the dynamics of the modern city were making these approaches nearly irresistible. The city was thus paradoxically both frustrating

to those looking for love and, at the same time, the “place of the enlarged horizon of opportunities.”19

The definition of love was itself also contested terrain, and these muddy conceptual waters raised the stakes even further. For the most part, middleclass society at the turn of the century approached love warily. Love marriages had famously been on the rise since the beginning of the nineteenth century, but strategic unions remained the favored middle-class means of connection. Casual sexual relationships were common enough but not acknowledged in public; nor were these allowed to count as “love.” And love—where it was so named—was certainly always heterosexual for middle-class tastes.

For its part, the Meyers encyclopedia of 1905—a fixture of the respectable bourgeois home—defined love as “the irresistible impulse for union” and insisted somewhat provocatively that the purely physical nature of “sexual love” was something different altogether.20 Other references saw in love the very “will of the ‘race’ for procreation and evolutionary betterment,” while more cynical commentators, as historian Edward Ross Dickinson puts it, understood love as “really just the need for a highly desirable item of consumption—sex.”21

In this book, love as a category of analysis extends beyond sex; indeed, it refers both to a discursive set of values and conventions, on one hand, and, on the other hand, to the totality or interwoven sum of affections, connections, desires, and tendernesses that were so magnetic and deeply meaningful for the men and women whose lives fill these pages. At the same time, the modern metropolis effectively decoupled love and sex more than ever before. Prostitution, fleeting liaisons, and pragmatic unions forged out of economic necessity (to able to afford an apartment, for example) all moved sex further away from “emotional unity” or something necessarily deeply meaningful. Even though love and sex surely continued to go hand in hand for some, the inverse was potentially true for a great many others. By that same token, intimacy, as in physical or emotional closeness, also acquired a new set of meanings in the city. Whether close, physical and emotional connection with others or mere companionship, intimacy is located somewhere between love and sex on a spectrum of emotions, though it is perhaps harder in the abstract to isolate intimacy from either love or sex. After all, one often found intimacy in loveless sex, and it is intriguing to consider the massive business of urban prostitution at the turn of the century as not just an economic exchange but also the search for physical and emotional intimacy.

Same-sex love was complex in an age when both sex and marriage were illegal and had to exist in a liminal, risky space outside the public eye. This book

is keenly interested in the contours of same-sex love and intimacy in turnof-the-century Berlin, as it was how a not insignificant portion of Berlin’s residents found love in the city. Same-sex love also in many ways reflects doubly the problems, anxieties, strategies, and ambiguities of love, respectability, and risk at the turn of the century. After all, the city may have opened new horizons of opportunities for gays and lesbians when compared with smaller towns and villages, but it also proved especially isolating, alienating, and even dangerous for them, given deeply entrenched cultural biases and long-standing legal statutes with serious punishments.22

There is no chapter or section of this book dedicated to the men and women who navigated the tricky world of same-sex relationships; instead, their story is woven into the discussion of heterosexual love, as they illustrate common trends with particular clarity. Love and intimacy perhaps took on slightly different forms for same-sex lovers in some circumstances, but connection, closeness, belonging, and stability meant the same thing for straight and same-sex couples alike. Accordingly, this book seeks to unite gay history with straight history. The very real differences in gay and straight experiences must, of course, never be effaced, but insisting on a strict boundary between straight and same-sex histories merely reinforces the long-standing isolation of these experiences as mutually unintelligible. Exploring them together— and dissecting their similarities and differences—helps make sense of both experiences separately. The time has come to merge these stories.23

Love—whether straight or same sex—is in any case difficult to pin down in historical sources. Happy lovers often produce little by way of concrete evidence of their love. Unhappy lovers, on the other hand (not to mention the lovesick, broken-hearted, and vengeful), tend to leave behind an impressive trail of material. This book relies as much on sources that were produced in the absence of love as on texts composed in the delirium of found love. It also seeks out other registers of love: marriage, dating and courting, intimacy, sex, divorce, murder, crime, the law, and even death. The chapters of this story of love in turn-of-the-century Berlin approach love from different angles: loneliness and desire; dating and individualization; bachelorhood, spinsterhood, and “free love”; and newspaper personal ads. In doing so, this book attempts to portray the totality, complexities, and tensions of the search for love in Berlin around 1900.

A great many of the stories and voices presented in this book come from the pages of Berlin’s daily newspapers. Urban dailies like the Berliner Morgenpost and the Berliner Lokal-Anzeiger are indeed rich sources for

turn-of-the-century urban life, and the newspaper has long been hailed as a critical feature and forum of intellectual exchange in modern life. In Berlin, specifically, reading newspapers was perhaps the most typical, emblematic turn-of-the-century activity. Day after day, edition after edition, newsprint shaped and transformed the way Berliners understood the city around them.24

But vibrant and important as they were and are, newspapers can also be deceiving. The stories and dramas pull one in, make one believe that each aged and brittle page (or, more commonly, microfilm reel) is a window through which the unmitigated past can be observed. But of course this is not the case. The Berlin that existed in the columns of the daily newspapers did not map perfectly onto the real Berlin in which people like Frieda Kliem worked and danced and moved about.25 After all, it was a stylized, imagined, and emplotted city, one that registered the predilections of the writers and was marketed to its readers; one that was fit to deadlines and the moods of editors and squeezed into last bits of free space on a page. The newspaper formed a triangular relationship with the city insofar as it described, shaped, and was shaped by Berlin around 1900.26

Berliners talked about their city and about themselves, both the reality and the fantasy, and the text and discourse this created was a crucial part of what it meant to live in a city that was on the cutting edge of modernity. This was particularly true in matters of love and intimacy, for so much of a person’s tastes, habits, ideals, norms, and practices was molded by the material she read and the fantasies she (or those around her) constructed for herself. Indeed, whether it was a news story about a personal ad swindling, an advice column about the propriety of bicycle riding, a readers’ forum on making potentially intimate acquaintances on the street, a front-page column about men who avoided marriage and opted to extend their bachelorhood, or a serial novel about a workplace romance—all of which reflect to some degree how Berliners were living—these not only shaped the way Berliners thought about love and intimacy in their city but also influenced the way they looked for and reacted to love in their own lives. After all, they, too, were part of the city, and they made sense of their own lives according to urban narratives of love.

It is therefore important to hold newsprint narratives and social practices in tension when examining Berliners’ lives at the turn of the century. When newspapers wrote about so-called eternal bachelors, for example, it was easy to believe that all Berliners had abandoned marriage for good. So, too, did columns about old maids, swindlers, modern girls, frustrated singles, and the disappearance of “mother’s way” make it seem as if each of these trends was completely taking over the city. In reality, these were, for the most part,

exceptional phenomena that were remarkable precisely because they were emerging but minority trends. They also made for fantastic copy. It was quite the same with the ubiquitous talk of newness, which was as much the reimagining of the old as new as it was actual revolutionary change. Finding love in the metropolis was a perplexing problem, but most Berliners ultimately did find love or at least got married and found some measure of intimacy. Statistics show that connection and marriage were not dying out but actually relatively healthy—evidence that Berlin was, strictly speaking, not the unassailable romantic antagonist it was often made out to be. With these caveats in mind, the problem of love and the rise of the new in the modern city were nevertheless exceedingly important narratives in turn-of-the-century Berlin. Even if most Berliners found spouses, the centrality of these discourses influenced the way Berliners lived their lives, raised their children, played matchmaker with their friends, and even understood their own relationships.27

Within these pages, newspaper tropes of love and modernity are situated against the many other sources of romantic discourse at the turn of the century, such as novels, plays, scientific articles, literary journals, diaries, memoirs, and police reports. However, daily newspapers do, in fact, offer the richest collection of evidence about everyday, ordinary lives from this era. The articles, columns, readers’ letters, and serial novels that form the foundation of the following analysis are not the eccentric writings of anomalous, aberrant individuals; they are urban narratives that circulated by the millions throughout the city and formed the basis for many more conversations around dinner tables, in the seats of trams and buses, and at cafés and bars throughout the city. They also prompted responses, dialogues, and debates that found their way back into the newspaper, which allows for observation of how newspaper copy was digested, perceived, and measured against reality, even if features like letters to the editor were also shaped by editors.28 And while Berlin’s major newspapers generally catered to their predominantly working-class readership in a heavily working-class city, this is also what makes them such useful sources for the present study.29 Indeed, in the stories they covered, the features they ran, and the viewpoints they presented, daily newspapers not only reinforced the allure of middle-classness but also seem to have addressed primarily those Berliners who were poised to achieve middle-class status or who teetered on the edge of losing it, people, in short, like Frieda Kliem.

The backdrop of the story of Frieda Kliem—the turn-of-the-century city—is more than window dressing or generic stage scenery. This book

argues that the conditions and opportunities of the city created desires for, avenues to, and new risks of love and dating around 1900. The city, then, is itself an important cast member of this story. This book is set specifically in Berlin, not only because it is where Frieda Kliem lived, but also because Berlin at the turn of the century was regarded as the most electric, dynamic, and fluid city in all of Europe. But this book is also about more than a single city at the turn of the century. It is about urban environments and the way urbanites navigated them, how they interacted with each other, and how they narrated their experience.

But what was it about Berlin, specifically, that allows it to speak for other urban environments? It is certainly true that the evolving pressures and impulses of city life, the complicated relationship between twentiethcentury Europeans and their nineteenth-century roots, and the always-tricky negotiation of class and gender norms were present in any number of turnof-the-century cities.30 Paris and London are also more famous as nineteenthcentury capital cities.31 But the characteristics that made twentieth-century cities distinct, whether the unprecedented intracity mobility, the lack of sustained connections to the surrounding countryside, or the self-consciously urban culture, were all present in Berlin in unique ways.32 Berlin was unique in its rapid rate of growth, its overwhelmingly young, fluid, and unattached population base, and the fact that these new Berliners did not self-segregate into ethnic neighborhoods. These factors raised the stakes in the search for love and intimacy.

The fact that Berlin was the place of heightened romantic opportunity and risk was not lost on contemporary observers. Berlin attracted the attention of some of the most insightful urban sociologists, theorists, and philosophers of the early twentieth century, and its newspapers were filled with notes and travel reports by curious visitors from all over the world.33 Regular people noticed it, too, and Berlin became one of the world’s first destinations for sex tourism, as Berlin authorities noted nervously at the time.34 Talk about Berlin ranged from concern to fascination, but nearly all voices concluded that the risks and rewards of modern dating were as clear to see in Berlin as anywhere else in the world.

The Berlin of this book is best understood as part of a larger typology, one that includes not only the standard list of great European cities but also a wide variety of urban contexts from Shanghai to Buenos Aires to Cracow.35 To be modern, to be urban—these were about much more than growth or industrialism or technology or the western hemisphere; the modern metropolis engendered an aesthetic all its own: a quality of living, a pattern of expression,

and a mode of interaction. Berlin cannot, of course, speak for the entire realm of meanings and methods of the modern world; but in exploring one aspect of turn-of-the-century urban life—love—this book aims to define some of the contours of this typology based on one of the most exemplary metropolitan environments.

The tensions between exceptional and representative, discourse and reality, and ordinary and celebrity are woven through each chapter of this book, and this fits perfectly with Frieda Kliem. Frieda was at once a celebrity and a totally unknown seamstress; her life was unquestionably—tragically—real, yet we know about it only in mediated, narrated, and emplotted forms. While Frieda’s life was representative of the way Berliners lived and loved, her struggle to find love, not to mention her violent death at the hands of a personal ad killer, was absolutely exceptional.

The structure of the book harnesses the tensions embedded in Frieda’s life in order to achieve a deeper, more nuanced analysis of the search for and navigation of love in turn- of-the- century Berlin. Each chapter opens with a period of Frieda’s life and explores the themes with which that part of her life intersects. Chapter 1 begins with Frieda’s arrival in Berlin and follows her as she struggles to fit herself to the urban environment, economy, and interpersonal dynamics. Chapter 2 sees Frieda finding her footing and stepping outside the lines of acceptable femininity and respectability as she pursued avant- garde paths toward intimacy that were more fleeting and individualistic than those of previous generations. Frieda’s prospects for marriage— and its alternatives— form the beginning of chapter 3, which examines the debate sparked by the growing number of Berliners who sought to revise long- standing beliefs about marriage and adapt them to the modern world. Chapter 4 explores Frieda’s use of newspaper personal ads and examines the matchmaking services and personal ads that represented revolutionary approaches to love and dating in the modern metropolis. Chapter 5, finally, delves into the trial of Frieda Kliem’s murderer. After analyzing the legal strategy of the defense attorney, courtroom exchanges between judge and defendant, and the trial’s dramatic ending, it concludes by considering the risks and rewards of love in the modern metropolis.