Acknowledgements

My firstthanksgototheArtsandHumanitiesResearchCouncilandtheBritish Academyforgenerouslyfundingperiodsofresearchleavewithoutwhichthis bookcouldnothavebeenwritten.TheSasakawaFundenabledaneye-opening visittoarchivesandmuseumsinJapan.IamextremelygratefultoTrinity CollegeandtheFacultyofEnglishLanguageandLiteratureatOxford,and wouldliketoacknowledgeinparticularRosBallaster,EllekeBoehmer,Seamus Perry,andHelenSmall.AlsointheEnglishFaculty,DavidDwan,LauraMarcus, andDavidRussellhaveprovidedabracingmixtureofintellectualstimulusand camaraderie.InTrinityCollege,myspecialthanksgotomycolleaguesKantik GhoshandBeatriceGrovesfortheirsupportandfriendship.

Theideasdiscussedinthisbookhavetakenshapeoveralongperiodoftime, evolvinginthecourseofmanyconversationsandtravels.DuringmyAHRC fellowshipIwasfortunatetoworksidebysideClémentDessy,whosharedwith mehisknowledgeofliterarycosmopolitanism,periodicals,theBelgianand French findesiècle,andmuchelsebesides.PhilipRossBullock,ClémentDessy, MichikoKanetake,CatherineMaxwell,JosephineMcDonagh,andValerieWorth allreadandcommentedononeormoredraftchapters.Ihaveprofitedenormouslyfromtheirinsights.Severalmorecolleaguesandfriendshavegivenadvice, criticism,andpracticalhelp,orcollaboratedonactivitiesconnectedtothe researchofthisbook.Amongthose,Iwouldliketoexpressmygratitudeto EmilyApter,RebeccaBeasley,LaurelBrake,LuisaCalè,DenisEckert,Emily Eells,HilaryFraser,RegeniaGagnier,AnalíaGerbaudo,KatharinaHerold, RichardHibbitt(withwhomIsharedmy firstforayintoliterarycosmopolitanism inourjointissueof ComparativeCriticalStudies ),DaichiIshikawa,BonKoizumi, KristinMahoney,SandraMayer,AlexMurray,AyakoNasuno,TinaO’Toole,Tim Owen,AnaParejoVadillo,MatthewPotolsky,LloydPratt,FraserRiddell,Gisèle Sapiro,andAkikoYamanaka-Binns.SpecialthanksareduetoJosephBristow, ToreRem,MargaretD.Stetz,andBirgitVanPuymbroeckfortheirextreme generosityinsharingresearchandhistoricalsourceswithme.

Writingaboutcosmopolitanismteachesonetoappreciatethegiftofhospitality. Forthisreason,IwouldliketoofferspecialthankstoGesaStedmanandthestaff oftheCentreforBritishStudiesoftheHumboldt-UniversitätzuBerlin,whichhas beenahomeformeformanyyears.Aconsiderablepartofthisbookwaswritten duringvariousstaysinBerlin.ThechapteronLafcadioHearnwaswrittenlargely inParis,duringmytenureasvisitingprofessorintheSorbonne,forwhichIam extremelythankfultoCharlotteRibeyrol.Otherinstitutionsthathaveinvitedme

topresentworkinprogressincludetheuniversitiesofAmsterdam,BardCollege Berlin,Birkbeck,Birmingham,Bologna,Bordeaux,Bristol,Chicago,Copenhagen, Exeter,Georgia(Athens,USA),Glasgow,Lille3,ParisSorbonne,Pisa,Royal Holloway,Milan,Stockholm,Sussex,UCLA,andVienna.Mygratitudegoesto myhostsinalltheseplaces,whohavemademewelcomeandprovidedmewith invaluableopportunitiestoreceivefeedbackfromengagedaudiences:Joseph Bristow,GraceBrockington,MatthewCreasy,RoxanneEberle,CarlottaFarese, HannahField,HollyFling,LauraGiovannelli,RudolphGlitz,BéatriceLaurent, RuthLivesey,RonanLudot-Vlasak,JosephineMcDonagh,SandraMayer,Rebecca N.Mitchell,AlexMurray,FrancescaOrestano,LeneØstermark-Johansen, CarolinePatey,CharlotteRibeyrol,GinoScatasta,LauraScuriatti,GilesWhiteley. HeartfeltthanksarealsoduetoLeireBarrera-Medrano,AlexanderBubb,Katharina Herold,andSaraThorntonforinvitingmetopresentmaterialfromthebookat theirconferences.Ifeelparticularlyluckytohavebeenabletosharemyresearchin theseminaron ‘ThePoliticsofAesthetics’ attheFondationdesTreilles,forwhich IthankBénédicteCoste,CatherineDelyfer,andChristineReynier;andinthe InstituteforWorldLiteratureatHarvard,forwhichmythanksgotoDavid DamroschandDeliaUngureanu.Ialsooweahugedebtofgratitudetothemembers oftheWriting1900groupandtheAHRC-fundedDecadenceandTranslation Networkformanystimulatingconversationsthroughtheyears.

Significantportionsoftheresearchforthisbookhavetakenplaceinthe BodleianLibrary,theBritishLibrary,theButlerLibrary,theDepartmentof PlannedLanguagesoftheÖsterreichischeNationalbibliothek,theHarry RansomCenter,theHoward-TiltonMemorialLibraryofTulaneUniversity (NewOrleans),theNewYorkPublicLibrary,theNationalLibraryofNorway, ToyamaUniversityLibrary,andTheWilliamAndrewsClarkMemorialLibrary, UniversityofCalifornia,LosAngeles.Amongthelibrariansandarchivistswho havehelpedmeintheseplaces,IwouldliketothankinparticularElizabeth Adams,SarahCox,SharonCure,ScottJacobs,VivO’Dunne,EmmaSillett,and BernhardTuider.

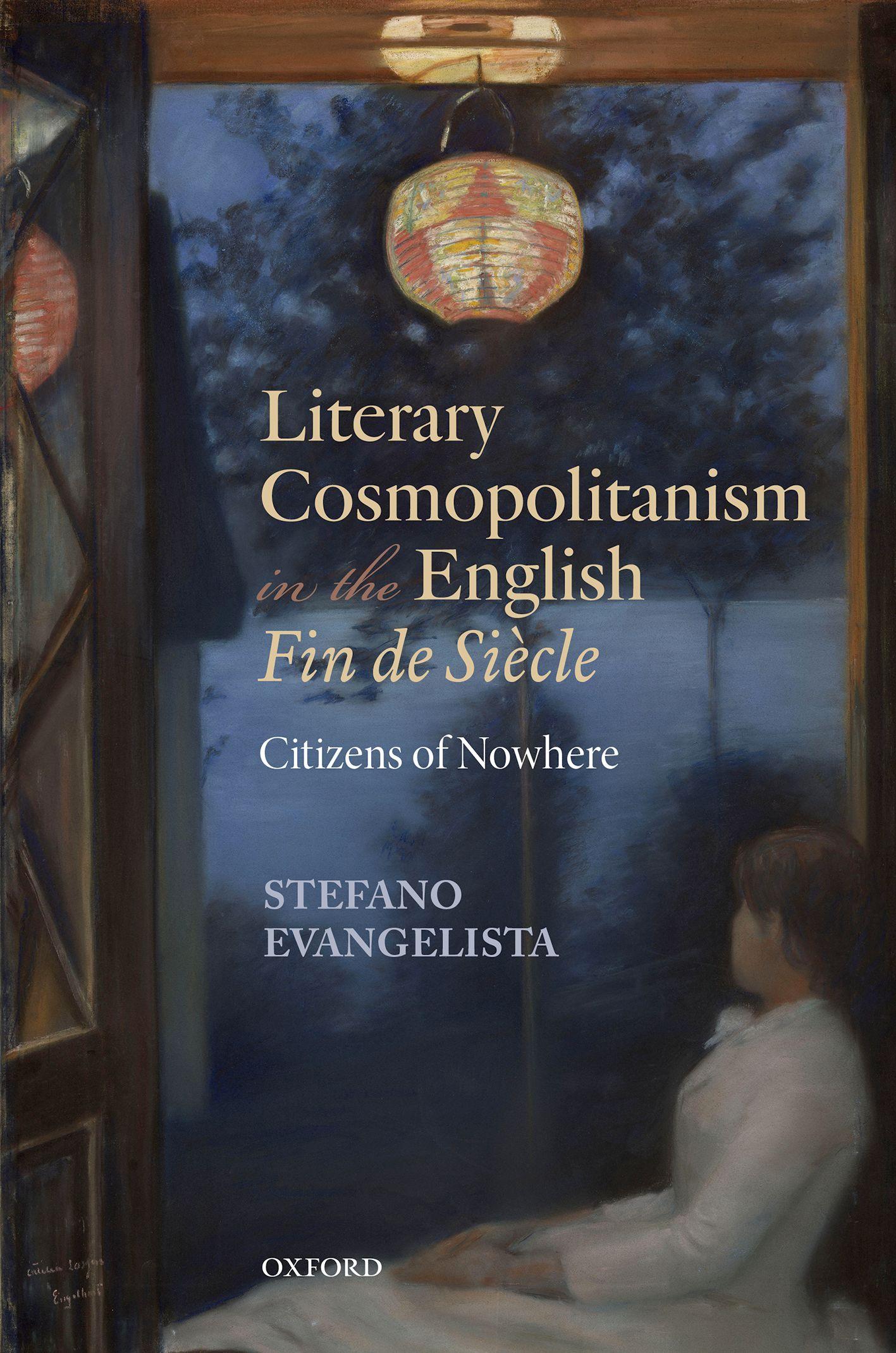

Fortheprovisionofimagesandpermissiontoreproducethem,Iwouldliketo acknowledgePunchCartoonLibrary/TopFoto;theMasterandFellowsof UniversityCollege,Oxford;Tate;theSammlungfürPlansprachenofthe ÖsterreichischeNationalbibliothek;andtheEsperantoAssociationofBritain. The ImperialFederationMapoftheWorld hasbeenreproducedfromCornell UniversityLibraryDigitalCollections,andthecoverimage,OdaKrohg’ s Japansk lykt (JapaneseLantern,1886)fromtheNationalMuseum,Norway.Ithankthe WilliamAndrewsClarkMemorialLibrary,UniversityofCalifornia,LosAngeles, forpermissiontoquotefromtheOscarWildeMSSandGeorgeEgerton’ scorrespondence;theHarryRansomCenter,TheUniversityofTexasatAustin,toquote fromtheJohnLaneCompanyRecordsandtheLafcadioHearnCollection;the HenryW.andAlbertA.BergCollectionofEnglishandAmericanLiterature,the

NewYorkPublicLibrary,Astor,LenoxandTildenFoundationstoquotefromthe LafcadioHearnpapers;theNationalLibraryofIrelandtoquotematerialfromOla Hansson’sletterstoGeorgeEgerton;andtheManuscriptsDivision,Special Collections,PrincetonUniversityLibrarytoquotefromSelectedPapersofMary ChavelitaBright(C0105).SomeofthematerialinChapter1haspreviously appearedinanessaytitled ‘CosmopolitanClassicism:WildebetweenGreece andFrance’,in OscarWildeandClassicalAntiquity (OUP,2017).Mythanksto KathleenRileyandtheothereditorsofthatvolumeforallowingmetouseit againhere.

Finally,myheartfeltthanksgotoJacquelineNorton,whohasbeenanideal editor,andtoAimeeWright,whohasguidedmethroughtheprocessofproductionatOUP.

ListofIllustrations xii

NoteonTranslations xiii

Introduction.TheSmallWorldofthe FindeSiècle 1

1.OscarWilde’sWorldLiterature32

2.LafcadioHearnandGlobalAestheticism72

3.GeorgeEgerton’sScandinavianBreakthrough117

4.ControversiesinthePeriodicalPress: Cosmopolitan and Cosmopolis 164

5.ThoseWhoHoped:LiteraryCosmopolitanismandArtificial Languages206 Conclusion.CitizensofNowhere:OneLastGhost256

Introduction

TheSmallWorldofthe FindeSiècle

Whatdoesitmeantoliveinacosmopolitanage?Inanessayfrom1892,Walter Patersuccinctlydefinedthelatenineteenthcenturyas ‘sympathetic,eclectic, cosmopolitan,fullofcuriosityandaboundinginthe “historicsense”’.¹Itis impossiblenottobestruckbyPater’sinclusionofcosmopolitanismalongside suchkeywordsofVictorianliberalhumanismassympathyandcuriosity.Pater, whowasnearingtheendofhiscareerasoneofBritain’sforemostcriticsand stylists,hadneverusedthiswordbeforeinprint.Henowassociatedcosmopolitanismwithhabitsofdiscriminationandcomparisonthatcharacterizedgood criticism:itdenotedatypeofintellectualdistinctionthatcombinedpowerof observationwiththecapacitytosituateone’spointofviewalwaysinalonger historicalperspectiveandinrelationtothewiderworld.InPater’sspecific context,thismeantlookingbeyondandmaybeagainstthegrainofEnglishculture fornewideasandoutlooks whichexplainsthelinktoeclecticismand,laterin thesameessay,totheactof ‘removingprejudice’.²Givenhownotoriously painstakingPaterwasinhischoiceofwords,hisprominentreferencetocosmopolitanismasanattributeofthe ‘geniusofthenineteenthcentury ’ shouldgive uspause.³

DerivedfromtheancientGreekfor ‘worldcitizenship’,cosmopolitanismasks individualstoimaginethemselvesaspartofacommunitythatreachesbeyondthe geographical,political,andlinguisticboundariesofthenation.FortheGreek cynicphilosopherDiogenes,whoiscreditedashavingcoinedtheterm,cosmopolitanismwasacategoryofresistanceandnon-belonging.Whenaskedwherehe camefrom,Diogenesmemorablyretortedthathewas ‘acitizenoftheworld’ (κοσμοπολίτης),implyingthathisoutlookandloyaltieswouldnotbeboundby thelimitsofanyone polis orstate.⁴ ClosertoPater’stime,ImmanuelKantposited thedesirabilityof ‘auniversal cosmopolitanexistence’ thatwouldenablepeople fromallnationstojointogetherina ‘greatfederation’,wheretherightsand

¹WalterPater, ‘Introduction’,in ThePurgatoryofDanteAlighieri:AnExperimentinLiteralVerse Translation,tr.C.L.Shadwell(LondonandNewYork:Macmillan,1892),pp.xiii–xxviii(p.xv).

²Ibid.,p.xvi.³Ibid.,p.xiv.

⁴ DiogenesLaertius, DiogenisLaertiiVitaePhilosophorum,ed.MiroslavMarcovich,3vols(Stuttgart andLeipzig:Teubner,1999–2002),i,414(6.63).

LiteraryCosmopolitanismintheEnglish FindeSiècle: CitizensofNowhere.StefanoEvangelista, OxfordUniversityPress.©StefanoEvangelista2021.DOI:10.1093/oso/9780198864240.003.0001

2

securityofallwouldbesafeguarded.⁵ Kant,whoalsodevelopedtheideaof universalhumanrights,sawcosmopolitanismasagreatpoliticalandethical project,integraltotherealizationofthecivilizingmissionoftheEnlightenment. ButwhileforKantcosmopolitanismwasautopianvisionor,atbest, ‘afeeling [that]isbeginningtostir’ , ⁶ forPateritwaspartofthematerialandhistorical realityofthepresent.Crucially,itwasalsointimatelyassociatedwithliterature.It issignificantthatPater’sremarksoccurintheintroductiontoanewtranslationof Dante.TheconceptofcosmopolitanismenablesPatertoexplaintheuniversal appealofDante,thatis,thequalitiesthatmakehisworkreadilyintelligibleand attractivetodifferentagesandnations,eventhroughthedistancingmediumof translation.Atthesametime,cosmopolitanismreferstoadistinctiveliterary orientationofthepresentthat,moreandmore,removes ‘certainbarrierstoa rightappreciation’ offoreignauthors,suchasDante,and,insodoing,makes readerslessinsularintheirtastes,moreopen-minded,andreadiertovalue ‘strangeness ’ asapositivequality.⁷ Infact,PateropenlycontraststhecosmopolitanismofhistimewiththefailureoftheeighteenthcenturytoappreciateDante: ‘Ifthecharacteristicmindsofthelastcentury,forinstance,wereapttoundervalue him,thatwasbecausetheywerethemselvesofanagenotofcosmopolitangenius, butofsingularlylimitedgifts,giftstemporaryandlocal.’⁸ Counterintuitively,the loftyabstractidealsoftheeighteenthcenturyledtoatypeofnarrowness, accordingtoPater,whereasthenineteenthcenturyiswhencosmopolitanism becomesatrueconstituentofthemodernityoftheage.

Pater’sattempttoreclaimcosmopolitanismwassymptomaticofaperiodin whichthisconceptcameunderincreasingpressurefromwriters.Somethree decadesearlier,CharlesBaudelaire whosewritingswerefoundationalforPater andhisEnglishcontemporaries hadlaidoutthecosmopolitantendenciesof artisticmodernityinhisessay ‘ThePainterofModernLife’ (‘LePeintredelavie moderne’,1863).Baudelairedefinedcosmopolitanismastheabilitytoinhabit multiplepointsofview whathecalledbeing ‘oftheentireworld’—and,atthe sametime,thedesire ‘toknow,understandandappreciateeverythingthathappensonthesurfaceofourglobe’ ⁹ Thisclearlyimpossibleambitionwasthe productofaworldwhereadvancesintransport,media,andcommunication technologiescompressedgeographicalspaceandacceleratedtheinternational

⁵ ImmanuelKant, ‘IdeaforaUniversalHistorywithaCosmopolitanPurpose’ [‘Ideezueiner allgemeinenGeschichteinweltbürgerlicherAbsicht’],in Kant’sPoliticalWritings,ed.HansReiss,tr. H.B.Nisbet,2ndedn(Cambridge:CambridgeUniversityPress,1990),41–53(51,47).

⁶ Ibid.51. ⁷ Pater, ‘Introduction’,in ThePurgatoryofDanteAlighieri,pp.xv,xvii.

⁸ Ibid.,p.xxiii.

⁹ CharlesBaudelaire, ‘ThePainterofModernLife’,in ThePainterofModernLifeandOtherEssays, tr.JonathanMayne(NewYork:DaCapo,1986),1–40(7).Thequotationsinthemainbodyofthetext aretakenfromthisEnglishtranslation;theFrenchoriginalinthefootnotesisfromBaudelaire, ‘Le Peintredelaviemoderne’,in Critiqued’art,suivideCritiquemusicale,ed.ClaudePichois(Paris: Gallimard,1992),343–384(‘Hommedumonde,c ’est-à-direhommedumondeentier[...]ilveut savoir,comprendre,appréciertoutcequisepasseàlasurfacedenotresphéroïde’,349).

circulationofideas.Inthisnew,smallworldofthelaternineteenthcentury, especiallyasviewedfromBaudelaire’svantagepointinmetropolitanParis,individualsweremoreintellectuallymobilethaneverbeforeand,crucially,readierto appreciatewhatcamefromdifferentpartsoftheglobe.Asaconsequence, cosmopolitanismalsomeantaheightenedstateofreceptivitytowardsimpressions andsensualstimuli.InBaudelaire’sglossonDiogenes’ famousdefinition,this combinationofworldlinessandhypersensitivitymadethecosmopolitansubject ‘thespiritualcitizenoftheuniverse’,¹⁰ wherethespiritualcitizenshipofcosmopolitanismrepresentedaradicalalternativetoJohannGottfriedHerder ’snotion of Volkesgeist,or ‘spiritofthepeople’ (towhichweshallreturnshortly),andideas ofcitizenshipespousedbythemodernnationstates.Indeed,althoughneitherof themsaidsoexplicitly,bothPaterandBaudelairecelebratedcosmopolitanismasa spiritualforcethatchallengedandcorrectedtheculturalnationalismoflarge nationssuchasBritainandFrance,imaginativelydrivingtheindividualtowards strangersandforeignspaceinsearchofnewidentitiesandnewideas.For Baudelaire,whoseversionofcosmopolitanmodernitywasaltogethergrittier thanPater’sliberalandratherbookishideal,thissearchcouldleadtodangerous places: ‘akindofcultoftheself ’ andothertypesofantisocialdesiresinfamously associatedwithdecadence.¹¹

ThedialoguebetweenPaterandBaudelairebringstolighttwokeyideasthis booksetsouttoexplore.The firstisthat,intheyearsaroundtheturnofthe twentiethcentury,literaturebecameanimportantmediumforsimultaneously promotingandinterrogatingcosmopolitanism atopicthathadpreviouslybeen largelyconfinedtophilosophicaldiscussion.Intheliteratureofthe findesiècle, cosmopolitanismtookshapenotasanabstractidealbutassomethingthat informedtheactual,livingpracticesofauthorsandreadersastheyexperimented withnewwaysofrelatinglocalandglobalidentitiesinaworldthattheyexperiencedasincreasinglyinterconnected.Thesecondisthatcosmopolitanismwas then,asitisnow,acontestedconceptthatgenerateddebateanddisagreement. PaterandBaudelairebothembracedthecosmopolitanideal,buttheirinterventionsoccurredwithinalargelyhostileculturethatdenouncedcosmopolitanismas politicallyandmorallysuspect,andstressedinsteadtheresponsibilitiesofliteraturetowardsthenation.Mysubtitle, CitizensofNowhere,emphasizesthissenseof controversybyadoptingadistortionofDiogenes’ formula(‘Iamacitizenofthe world’)thathasbeenrepeatedlyusedtostiflecosmopolitansentimentandfuel nationalism.Baudelairehimselfhintedatthisdiscourseofalienationandnonbelongingwhenhecharacterizedcosmopolitanismastheabilitytobesimultaneously ‘awayfromhomeandyettofeeloneselfeverywhereathome’.¹²Baudelaire

¹⁰ Ibid.(‘citoyenspiritueldel’univers’,349).

¹¹Ibid.27(‘uneespècedecultedesoi-même’,370).

¹²Ibid.9(‘Êtrehorsdechezsoi,etpourtantsesentirpartoutchezsoi’,352).

4

viewedthisconditioninapositivelight,asastrategyofradicaldefamiliarization thatpresentedattractiveadvantagesintheartisticandsocialspheres.However, thesameattitudethatpotentiallyenablesthecosmopolitansubjecttobelongin differentspacesandcontextsalsoplaceshimorheratriskofbecomingastranger anywhere,thatis,ofweakeningthesocial,linguistic,cultural,andaffectiveties thatmakeindividuals ‘athome’ inacommunity.Inthe findesiècle,thisparadoxicalnatureofcosmopolitanismstartedtoemergeclearly:itwassimultaneously apositionofstrengthandvulnerability;ageneralizedconditionofmodernityand aformofexceptionalismthatsetsomeindividualsapartfromtherestofsociety.

Inaseriesofdefinitionsthat,likePater’s,harkbacktothecorevaluesofliberal societies,KwameAnthonyAppiahhaslinkedcosmopolitanismtothecelebration of ‘thevarietyofhumanformsofsocialandculturallife’,thecherishingof ‘local differences’,andtherespectforminorities(national,ethnic,sexual,etc.)that facilitatealong-termprocessof ‘culturalhybridization’ ofhumanity.¹³Appiah’ s workbelongstoagrowingbodyofscholarshipinthehumanitiesandsocial sciencesthathasfocusedoncosmopolitanismsincethe1990s.Thisincludes importantinterventionsbyHomiK.Bhabha,PhengCheah,JacquesDerrida, PaulGilroy,JuliaKristeva,MarthaNussbaum,andBruceRobbins.¹⁴ Indifferent ways,thesecriticshaveallinterrogatedcosmopolitanismbecausetheybelieveit capableofprovidinganswerstosomeofthemostpressinggeopoliticalchallenges thatwefaceinthepresent:globalization,diasporas,displacement,massmigration, multiculturalism,andintegration,and,onemustnowadd,theresurgenceof xenophobicnationalismsandwhitesupremacyintheWest.Thetrendoverthe yearshasbeentoexpandtheconceptofcosmopolitanisminordertoemphasize itsplurality PhengCheahemphaticallyspeaksofthe ‘newcosmopolitanisms’— andtomakeitasculturallyinclusiveaspossible,inanattempttocorrectthe Eurocentricbiasofitsclassicformulations(e.g.Kant’s)and,sometimes,the Americanbiasofmuchofthecurrentdebate.¹⁵ Inthetwenty- firstcenturyasin

¹³KwameAnthonyAppiah, ‘CosmopolitanPatriots’ , CriticalInquiry,23.3(1997),617–639(621, 619,and passim).SeealsoAppiah, Cosmopolitanism:EthicsinaWorldofStrangers (London:Allen Lane,2006).

¹

⁴ HomiK.Bhabha, ‘Unsatisfied:NotesonVernacularCosmopolitanism’,inLauraGarcía-Moreno andPeterC.Pfeiffer,eds, TextandNation:Cross-DisciplinaryEssaysonCulturalandNationalIdentities (Columbia,SC:CamdenHouse,1996),191–207;CarolA.Breckenridgeetal., Cosmopolitanism (Durham, NC,andLondon:DukeUniversityPress,2002);JacquesDerrida, OnCosmopolitanismandForgiveness, tr.MarkDooleyandMichaelHughes(London:Routledge,2001);PaulGilroy, PostcolonialMelancholia (NewYork:ColumbiaUniversityPress,2005);JuliaKristeva, StrangerstoOurselves,tr.LeonS.Roudiez (NewYork:ColumbiaUniversityPress,1991);BruceRobbinsandPhengCheah,eds, Cosmopolitics: ThinkingandFeelingbeyondtheNation (MinneapolisandLondon:UniversityofMinnesotaPress,1998); MarthaNussbaum, ‘PatriotismandCosmopolitanism’ , BostonReview,19.5(1994),1–6.Nussbaum’ s provocativeessaywascrucialintriggeringawaveofawarenessandcontroversyaroundcosmopolitanism inthelatetwentiethcentury;aseriesofresponsesarecollectedinJoshuaCohen,ed., ForLoveofCountry: DebatingtheLimitsofPatriotism (Boston:BeaconPress,1996).

¹

⁵ PhengCheah, InhumanConditions:OnCosmopolitanismandHumanRights (Cambridge,MA: HarvardUniversityPress,2006),19.SeealsoDavidA.Hollinger, ‘NotUniversalists,NotPluralists:The NewCosmopolitansFindtheirOwnWay’ , Constellations,8.2(2001),236–248;RobertJ.Holton,

thenineteenth,cosmopolitanismhasofcoursealsobeencriticizedbothfromthe rightandtheleft,whetherforitsroleinprovidingwaysofunderminingnational loyaltyorforbeingcomplicitwithcolonialmentalityandneoliberalpolitics.¹⁶ Ishallcomebacktosomeofthesecriticismsinthecourseofthechapters.For now,itisenoughtonotethatthisbookaimstoshowthatthedebateon cosmopolitanismthattookplaceinthe findesiècle laidthefoundationsforour ownunderstandingofthisconceptinthetwenty- firstcentury.Whilenotengaging explicitlywiththepoliticalsituationofthepresent,thisbookarguesthatliterature writtenoveronehundredyearsagoisfulloftensionsandinsightswhicharestill surprisinglyrelevanttokeyissuesthatpreoccupyustoday:theculturaland emotionalchallengesofmigrationanduprooting,thetoleranceofculturaldiversityinaliberalstate,theuneasybalancebetweenpatriotismandnationalism,the limitsofuniversalism,andthepressureofethicalobligationstowardsstrangersin aglobalsociety.Beforedelvingfurtherintohowliteraturedealtwiththeseissues, itisimportanttoconsiderthecomplexhistoryoftherelationbetweennationalism andcosmopolitanisminthenineteenthcenturyandthelatter’sriseasadistinctive socialidentity.

CosmopolitanismandNationalism

Wenowtendtothinkofcosmopolitanismandnationalismasirreconcilable oppositesbutthishasnotalwaysbeenthecase.Inthelateeighteenthcentury theGermanphilosopherJohannGottfriedHerderestablishedalinkbetween languageandnationhoodthatwouldformthebackboneoffuturetheoriesof nationalism.However,Herderwasalso,atonceandwithoutexperiencingthisasa contradiction,acosmopolitanandaninternationalist.Hebelievedthatthevariety ofhumanlanguageswasanundisputableproofofthedifferencebetweenone nationandanother;hearguedthateachnationhaditsownspiritualessenceor soul(Volkesgeist);buthedidnotthinkthatanyonenationoritscultureshouldbe seenassuperiortoothers.Herdercelebrateddiversity,notingthat ‘[i]nalmostall smallnationsofallpartsoftheworld,howeverlittlecultivated(gebildet)theymay be,balladsoftheirfathers,songsofthedeedsoftheirancestors,arethetreasureof theirlanguageandhistoryandpoeticart,[theyare]theirwisdomandtheir Cosmopolitanisms:NewThinkingandNewDirections (BasingstokeandNewYork:Palgrave Macmillan,2009);BruceRobbinsandPauloLemosHorta,eds, Cosmopolitanisms (NewYork:New YorkUniversityPress,2017);SheldonPollocketal., ‘Cosmopolitanisms’ , PublicCulture,12.3(2000), 577–589.

¹

⁶ ForexamplesofthelatterseeTimothyBrennan, AtHomeintheWorld:CosmopolitanismNow (Cambridge,MA:HarvardUniversityPress,1997);andHalaHalim, AlexandrianCosmopolitanism:An Archive (NewYork:FordhamUniversityPress,2013).

encouragement’.¹⁷ Hisnationalismwasbasedontheprinciplethatallnationshad equaldignity,even onecouldalmostsay,especially thepoliticallyoppressed ones.Herderwarnedagainstthedangersofnationsturninginwardonthemselves andclosingtheirborderstoforeigninfluences,andremindedhisGermancompatriotsofalltheyhadlearnedfromforeigncultures.¹⁸ Heheldthatthetransmissionofculturefromnationtonationwas ‘the finest bondoffurtherformation thatnaturehaschosen’.¹⁹ Formostofthenineteenthcentury,Kant’ s EnlightenmentmodelofuniversalistcosmopolitanismandHerder’sromantic particularism,withitsemphasisontheuniquenessofnationalcharacter,could existalongsideoneanother.²⁰ TheItalianpatriotGiuseppeMazzini,forinstance, wasbothatheoristofItaliannationalismandacommittedcosmopolitanwho campaignedforaunitedEurope.

Sometimeinthelatenineteenthcentury,however,ashiftoccurredthatcaused thetwotobifurcate.In1893,thehistorianC.B.Roylance-Kentobservedthatit wouldhavebeennaturaltosupposethattheincreasedcontactbetweenpeople fromdifferentnationswouldbythenhavecaused ‘acorrespondingadvancein cosmopolitanspiritandlatitudeofsympathy’.²¹However,quitetheopposite seemedtobethecase:everywhere,nationalistsentimentwas ‘runningtoexcess’ andtakingtheformofan ‘exuberantpatriotism ’ thatmanifesteditselfasa hostilitytowardsforeigners.²²Thisrecentphenomenon,whichRoylance-Kent deploredforhavingtakentheworldbackto ‘theruderhabitsofanearlierage’ , waspartoftheparadoxicalconditionofmodernity.²³CorroboratingRoylanceKent’sperception,historiansofnationalismnowseethe findesiècle asaturning pointthatmarkedtheemergenceofanewtypeofnationalism,which,inthe wordsofE.J.Hobsbawm, ‘hadnofundamentalsimilaritytostate-patriotism,even whenitattacheditselftoit.Itsbasicloyaltywas,paradoxically,notto “the country”,butonlytoitsparticularversionofthatcountry:toanideological construct.’²⁴ InBritainandalloverEurope,thebirthofthis ‘domesticnationalism ’

¹⁷ JohannGottfriedHerder, ‘TreatiseontheOriginofLanguage’ [1772],in PhilosophicalWritings, tr.anded.MichaelN.Forster(CambridgeandNewYork:CambridgeUniversityPress,2002),65–164 (147).ThequotationsinthemainbodyofthetextaretakenfromthisEnglishtranslation;theGerman originalinthefootnotesisfromJohannGottfriedHerder, ‘AbhandlungüberdenUrsprungder Sprache’,in WerkeinzehnBänden,ed.MartinBollacheretal.(Frankfurta.M.:Suhrkampf, 1985–2000),i: FrüheSchriften1764–1772,ed.UlrichGaier(1985),695–810(‘Fastinallenkleinen NationenallerWeltteile,soweniggebildetsieauchseinmögen,sindLiedervonihrenVätern,Gesänge vondenTatenihrerVorfahrenderSchatzihrerSpracheundGeschichte,undDichtkunst;ihre WeisheitundihreAufmunterung’,791).

¹⁸ Ibid.160.

¹⁹ Ibid.,italicsintheoriginal(‘dasfeinste BandderFortbildung,wasdieNaturgewählet’,806).

²⁰ SeeEstherWohlgemut, RomanticCosmopolitanism (Basingstoke:PalgraveMacmillan,2009).

²¹C.B.Roylance-Kent, ‘TheGrowthofNationalSentiment’ , Macmillan’sMagazine,69(Nov.1893), 340–347(340).

²²Ibid.344.²³Ibid.

²⁴ E.J.Hobsbawm, NationsandNationalismsince1870:Programme,Myth,Reality (Cambridgeand NewYork:CambridgeUniversityPress,1990),93.

fosteredthegrowthof ‘right-wingmovementsforwhichtheterm “nationalism” wasinfactcoinedinthisperiod,or,moregenerally,ofthepoliticalxenophobia whichfounditsmostdeplorable,butnotitsonly,expression,inanti-Semitism’.²⁵ This ‘fulfilment’ ofnationalismwaseffectivelyabetrayaloftheidealsespousedby Herderandtheromantics.²⁶ Frombeingassociatedwithliberalismandtheleft, nationalismturnedtobeing,inHobsbawm’swords, ‘achauvinist,imperialistand xenophobicmovementoftheright,ormoreprecisely,theradicalright’.²⁷ While governmentsmanipulatedthisnewnationalismtotheirownends(RoylanceKent,forinstance,reviewedawholeseriesofxenophobiclawsthathadrecently comeintoforceinvariouscountriesaroundtheworld),itisimportanttonotice thatitwasnotsimplyaphenomenonimposedfromaboveintheformofpolitical propaganda:itwasatthesametimeanideologyandtheexpressionofapopular sentimentthatgaverisetoextremelysuccessfulgrassrootmovements.Theradicalizednationalismoftheturnofthecenturyfedonnationalfeelingincomplex, sometimesdeliberateways,seeking albeit,obviously,notalwayssuccessfully to reorientpatriotismtowardsanilliberalposition,hostiletointernationalcooperationandfriendship.

Cosmopolitanism,withitsmillennialhistorythatstretchedallthewaybackto ancientGreece,longpredatedthebirthofthenationasapoliticalletalone ideologicalentity.Inthesecondhalfofthenineteenthcentury,itsabstract principlesformulatedbyKantweregivenmoreconcreteshapethroughthe proliferationofnew,organizedformsofinternationalism.Fromthefoundingof theInternationalWorkingMen’sAssociation,orFirstInternational,in1864to theestablishmentoftheInternationalLeagueforPeaceandFreedom(1867),the Second,orSocialist,International(1889),andTheHagueConventionsof1899 and1907,internationalismwasasprominentafeatureofthishistoricalperiodas thenationalismdescribedbyHobsbawm.Theselandmarkevents,andthemany internationalcongressesandinitiativesforstandardizationthattookplaceinthese years,givetheimpressionofagrowingconsensusthatthenationnolonger reflectedtheactualconditionsofaninterconnectedmodernworld,inwhich people,goods,andideasmovedacrossborders.However,RaymondWilliams, whodrawsahelpfuldistinctionbetweennationalismandnationalfeeling,cautionsusagainstseeingastarkoppositionbetweentheconceptsofnationalismand internationalism:internationalism ‘isonlytheoppositeofselfishandcompetitive

²⁵ Ibid.105.

²⁶ HansKohn, TheAgeofNationalism:TheFirstEraofGlobalHistory (NewYorkandEvanston,IL: Harper,1968),9–10.KohnandHobsbawmagreeindatingthisparadigmshifttotheyearsfromthe 1880stotheFirstWorldWar.SeealsoPaulLawrence,whodatestothisperiodthebirthofaprocessof culturalinquiryintotheprosandconsofnationalism;Lawrence, Nationalism:HistoryandTheory (HarlowandLondon:Longman,2005),17ff.

²⁷ Hobsbawm, NationandNationalism,121.

policiesbetweenexistingpoliticalnations’;²⁸ itdoesnotnecessarilyquestionthe fundamentalprinciplesofthenationasapoliticalandsocialentityoritsspiritual functiondescribedbyHerder.Williams’sinsightisborneout,inthisperiod,by theriseofmovementsofpan-Germanism,pan-Slavism,andpan-Latinism,which allbuiltbridgesbetweenexistingnationsonlyinordertoerectnewbarriers aroundthem,andreasserthighlyexclusiveformsofethnic,cultural,andsocial identity.Indeed,lookingspeci ficallyattheturnofthetwentiethcentury,the historianGlendaSlugahaschallengedtheengrainedpositionofnarrativesof nationalisminourunderstandingofhistory,speakinginsteadofalongsymbiotic relationshipbetweennationalismandinternationalismas ‘entangledwaysof thinkingaboutmodernity,progress,andpolitics’.²⁹

Withinthiscomplexand fluid field,cosmopolitanismprovidedphilosophical, emotional,andethicalargumentsthatintellectualsandactivistscouldusetocurb thespreadofanaggressivenationalism.Ina1900pamphletissuedbythe InternationalArbitrationandPeaceAssociation,thejournalistGeorgeHerbert Perrisdescribedthepresentasamomentofunprecedentedawarenessabout globalinterconnectedness:asitbecameincreasinglydifficultandindeedmeaninglesstoseparatedomesticandforeignaffairs,internationalrelationsassumed paramountimportance,inthepoliticalaswellastheethicalandculturalspheres. ForPerris,notonlywasthenationshowingsignsofdeclineasatypeofsocial organization,butthevery ‘spiritofnationality’ was finallybeingrevealedforwhat itwas a ‘myth’ : ‘itisinpartasuperstitionofmoreorlessignorantsentimentalists,andinpartapretenceofcertainclassesofpersonswhoareinvariousways interestedinthemaintenanceofthesuperstition’.³⁰ Perrissawthe ‘newinternationalism’ oftheturnofthetwentiethcenturyaspartofalonghistoryof cosmopolitanisminwhichthebirthandcollapseofthenationwasonlya shortchapter.Forthatreason,herecommendedthatthepresentmuststudy closelythe ‘cosmopolitanheritage’ ofthepast(bywhichhemeanttheclassicaland Judaeo-Christiantraditions),whoseresourceswerestilluntapped.³¹Perris believedthat,onlybylearningtoseethroughthesentimentalappealof nationalism,couldhiscontemporarieslaythefoundationsfornewethical andsocialstructuressuitedtothematerialconditionsofthemodernage. WhiletheEnlightenmentcosmopolitanismofKant,Goethe,andGoldsmith wasstillavalidmodel,itwasalso,forPerris, ‘avaguesentiment’ ,too ‘academicandarti fi cial’ ;thechallengeforcosmopolitanismwasthatitmust

²⁸ RaymondWilliams, Keywords:AVocabularyofCultureandSociety,rev.edn(NewYork:Oxford UniversityPress,1983),214.

²

⁹ GlendaSluga, InternationalismintheAgeofNationalism (Philadelphia:Universityof PennsylvaniaPress,2013),3.

³

⁰ G.H.Perris, TheNewInternationalism (London:InternationalArbitrationAssociation,[1900]), 35.OnPerris’sinvolvementintheInternationalArbitrationandPeaceAssociation,seePaulLaity, The BritishPeaceMovement,1870–1914 (Oxford:Clarendon,2001),133–138.

³¹Perris, NewInternationalism,32.

nowgrowintoa ‘popularandorganicideal’— itsphilosophicalideal,thatis, mustbebuiltintothetransactionsofeverydaylifeinaworldwheretravel, commercialrelations,andscienti fi candculturalcooperationwereallhappeningonaninternationalscale.³²Perry ’ spamphletshowshow,intandemwith thetransformationofnationalism,cos mopolitanismalsotookonanewidentityinthisperiod:itassumedanoppositionalcharacter,becameradicalized. Thischangedrewcontributionsfromawidesocialpoolthatwentfrom internationalistactivists,likePerrishimself,tobourgeoisliberalsandintellectuals,socialistinternationalists,anar chists,migrantgroups,feminists,homosexuals,theosophists,andproponentsofuniversallanguagemovements. Unlikethenationalists,thesescattere dsocialandpoliticalentitiesdidnot uniteunderasinglebannerbuttheirvarietygaveaspecialculturalenergyto thecultureofcosmopolitanismthatthisbookseekstoreconstruct.

If,inBenedictAnderson’sfamousargument,thenationderiveditscoherence asanimaginedcommunityfromprinttechnology,which ‘madeitpossiblefor rapidlygrowingnumbersofpeopletothinkaboutthemselves,andtorelate themselvestoothers,inprofoundlynewways’,theprintmediumcouldnow alsobeappropriatedforthecosmopolitancause.³³Evenwhenitdidnotcriticize nationalismexplicitly,theevermoreeffectiveandfar-reachingprintindustry ofthelatenineteenthcenturymadereadersmoreinternationalbyorienting themoutwards,beyondthehorizonsofexpectationssetbynationalborders. WithinEuropeatleast,bycirculatingtranslationsandforeignnews(including, crucially,culturalitems)withunprecedentedspeedandinunprecedentedquantities,thepresscreatedinternationalcommunitiesthatsharedtastes,interests,and culturalcodes:readersinLondon,Copenhagen,andMilanengagedinvery similarculturaldebates(e.g.thecontro versiesoverdecadenceandnaturalism) virtuallyatthesametime,developing inthisprocessnewbondsofidentity thattranscendednativecustoms.Unsurprisingly,oneofthemostcontested issuesamongtheenlarged,denationalizedcommunityofreadersofthe fin desiècle wastheverynatureandmeaningofcosmopolitanism.ShouldindividualandcommunalidentitiesberootedinHerder’ sideasofthe Volkesgeist ? Wasaworld-mapdividedintosmallparcelsoflinguisticandculturaluniquenesssomethingtoregretorcelebrate ?And,inthecaseofBritain,whatwas therelationshipbetweenthemultinationalcultureoftheempireandcosmopolitanideology?

³²Ibid.39.

³³BenedictAnderson, ImaginedCommunities:ReflectionsontheOriginandSpreadofNationalism (LondonandNewYork:Verso,1991),36.ForcritiquesofAnderson’smodel,withspecialrelevancefor literarystudies,seePhengCheah, ‘GroundsofComparison’ , Diacritics,29.4(1999),2–18;andJonathan Culler, ‘AndersonandtheNovel’ , Diacritics,29.4(1999),19–39.Thisjournalissueisentirelydedicated toresponsestoAnderson’swork.

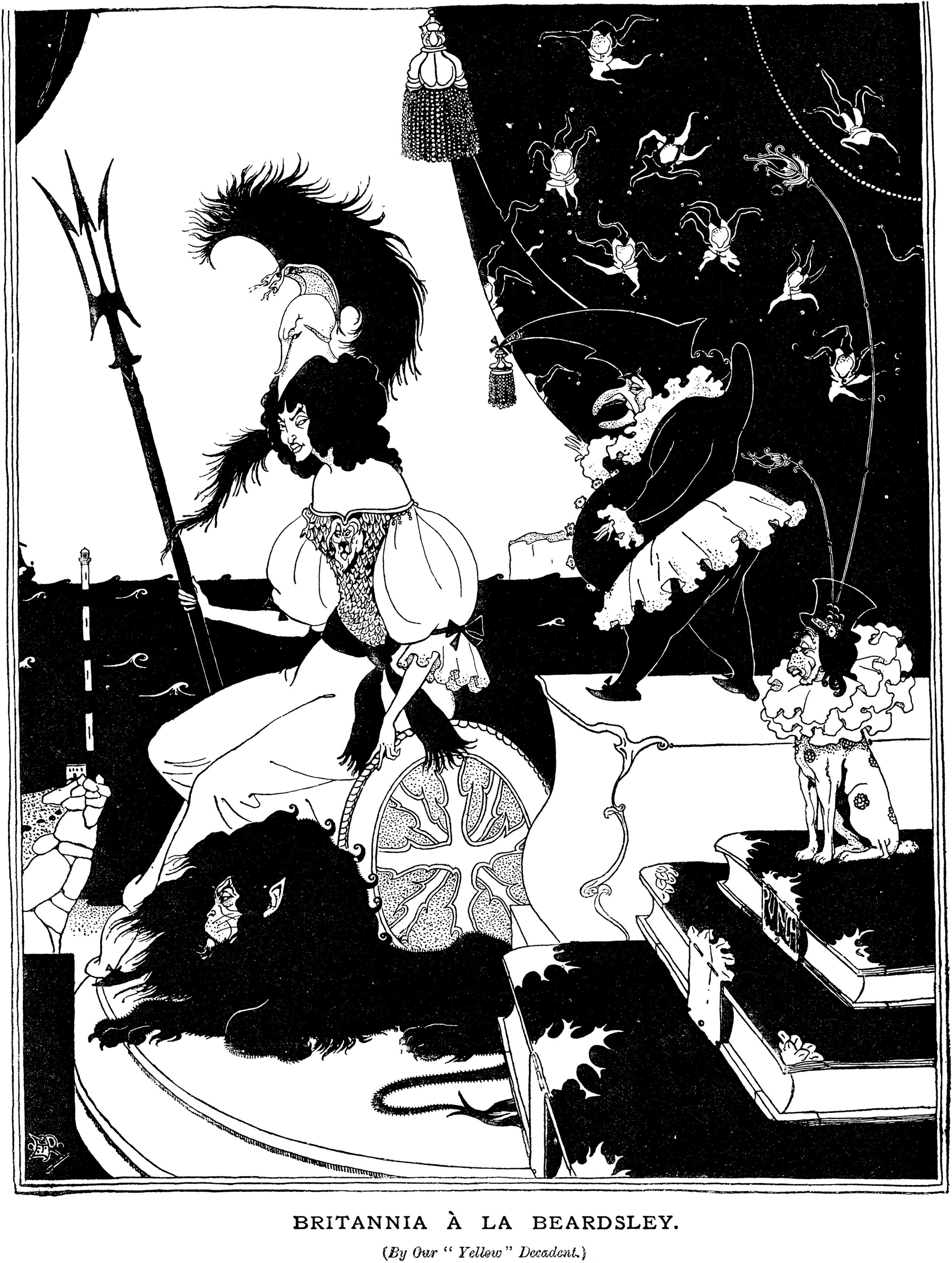

Wemustimaginetheconfrontationbetweennationalismandcosmopolitanism asaslowgameofpressures,frictions,andironies,onlyoccasionallyenlivenedbya visibleconflagration.Take,forinstance,acartoonthatappearedin Punch’ s Almanack in1895,titled ‘BritanniaàlaBeardsley’ (illustration0.1).Thedrawing showsanationalsymbolrefashionedthroughthecosmopolitansensibilityof AubreyBeardsley,anEnglishartistthenattheheightofhisfame:anarmoured androgynous figure itcouldbeawomanoramanindrag holdingBritannia’ s iconictridentandshieldis floatingontheseainthecompanyofananthropomorphiclionthatlooksabitlikeapoodleandothergrotesque figures.TheWhite CliffsofDoverarevisibleinthebackgroundand,intheforeground,anEnglish patrioticbulldogintophatandrufflesstaresproudlyahead,restingonapileof lavishlyboundvolumes.Thecaricaturist(EdwardT.Reed)hasskilfullyreproducedsignaturefeaturesofBeardsley ’sstyle:theframingofthepicturethrough theatricalcurtains,allusionstoeighteenth-centuryaesthetics,themixtureof classicismandthegrotesque,theassociationwiththeart-booktrade,andthe self-referentialjoke(thetomeonthetopofthepileisavolumeof Punch ).Hehas evenmanagedtocapturesometh ingoftheessenceofBeardsley ’sdrollhumour. Andwhatisfunnyispreciselytoseethathumourtrumpedbythecaricaturist, followingatraditionofavant-gardebashingthat Punch hadbeenpeddlingfor decades.Herethecosmopolitansympa thiesofprogressivemetropolitan typesareexaggeratedandmadetoclashwithnationalistsentimentinfrontof thereaders ’ eyes.AcosmopolitanartistlikeBeardsleyisshowntobeclearly un fi ttorepresentthenation.HisdistortedvisionofBritanniasuggestsatbest non-belongingand,atworst,calculate ddisloyalty.Thecartoongraphically demonstratesthatpatrioticandcosmopolitansentimentscannotthriveon sharedground.Weonlyneedtorememberthat1895wasalsotheyearofthe OscarWildetrials,andthatBeardsleyw ascloselyassociatedwithWildethrough hisdrawingsofthe1894Englishtranslationof Salomé (towhichthephysiognomyoftheandrogynousBritanniaall udes)torealizehowinsidiouslythis caricatureleveragestheanti-Wildesentimentthatdominatedpressreports, compoundingitwithnationalism,asahighlytoxicwarningtoBeardsleyand hiskind.

Nationalistsentimentwaseverywhereinlatenineteenth-centuryBritain:itwas institutionalizedinschoolsandBaden-Powell’sboyscouts,itwasturnedinto spectacleandentertainmentinmonumentsandmilitaryparades,itwasendlessly broadcastbythepopularpress.Nationalismwasgivenliterarycurrencyin jingoisticpoemsandpopularappealinmusic-hallsongs.Inmanyofthese institutionsandculturalproducts,patrioticandnationalfeelingsbecameexclusive andconfrontational,oftenturningintoaggressiveweapons.Moreover,asthe iconographyofBritanniainthe Punch cartoonremindsus,theoppositional relationshipbetweennationalismandcosmopolitanismwasfurthercomplicated bythepresenceoftheempire.Itisobviousthatnationalismprovidedan

Illustration0.1 ‘BritanniaàlaBeardsley’ , Punch’sAlmanack (1895).PunchCartoon Library/TopFoto

ideologicaljustificationforsomeoftheworstformsofpoliticalabuse,violence, andculturalaggressioncommittedinthenameoftheBritishEmpire.But,atthe sametime,theempirecreatedtheconditionsforanunprecedentedglobalmovementofpeople,goods,ideas,and,crucially,writersandtexts,fromandtothe Europeanmetropolis;asLeelaGandhihasshown,thisaidedtheformationof