LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

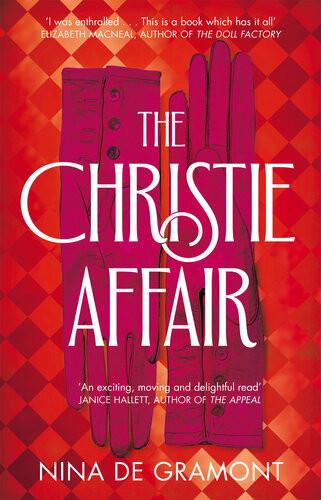

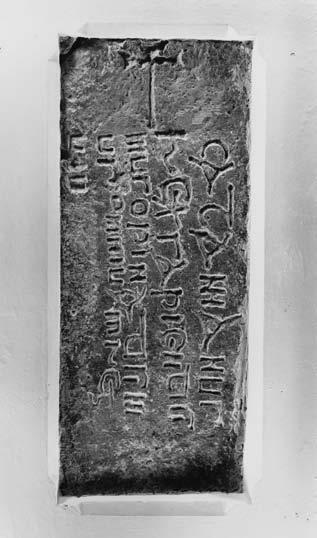

1.1. The inscribed stone at Llangadwaladr, Anglesey, commemorating King Catamanus (Cadfan) of Gwynedd. 5

1.2. Llangorse crannog, Breconshire, excavated in 1869. 11

1.3. The Lichfield Gospels, the end of St Matthew’s Gospel. 26

1.4. The opening page of the Martyrology in the Psalter of Rhygyfarch. 31

2.1. Wales: physical features. 36

2.2. Wales, showing the locations of pre-Roman peoples, early medieval kingdoms, and other regions. 39

2.3. Latin-inscribed stone commemorating Dervacus son of Iustus standing beside the Roman road, Ystradfellte, Breconshire. 45

2.4. Llangynfelyn trackway, Cors Fochno, Cardiganshire. 46

2.5. Wentlooge Level, Monmouthshire, showing a reconstruction of the evolution of the landscape between the Roman period and the eleventh century. 52

2.6. Sundial, Clynnog Fawr, Caernarfonshire. 59

3.1. Major events noted in the written sources relevant to the ending of Roman control in Britain. 66

3.2. Later Roman Wales: principal fourth-century sites and others mentioned in the text. 70

3.3. The walls of the civitas capital at Caerwent, with an additional mid-fourth-century bastion. 73

3.4. Roman-period rural settlements: comparative plans. 77

3.5. Late finds from the auxiliary fort at Caernarfon. 86

4.1. The auxiliary fort at Caernarfon, showing its spatial relationship. 106

4.2. The Roman legionary fortress of Caerleon and the Roman town of Caerwent, with later sites and other features. 108

4.3. Distribution of fifth- to seventh-century roman-letter- and ogham-inscribed stones. 115

4.4. Fifth- and sixth-century roman-letter and ogham inscriptions. 119

4.5. Later sixth-century, Latin-inscribed stone from Margam Mountain. 121

5.1. Early medieval settlement sites and some other possible sites. 136

5.2. Glanfred, aerial photograph. 138

5.3. The twin summits of Degannwy. 143

5.4. Comparative plans of hillforts and promontory forts. 145

5.5. Llanbedrgoch, plan of the enclosed settlement. 153

5.6. Llangorse crannog. 156

5.7. Farmsteads with evidence of early medieval occupation. 162

5.8. Geophysical survey of the open settlement at Rhuddgaer, Anglesey. 164

5.9. Excavated remains of an open settlement at South Hook. 167

5.10. Building plans. 168

5.11. Diagram of the promontory fort at Dinas Powys, showing internal use of space. 178

6.1. Early medieval estates donated to the Church recorded in charters in the Book of Llandaf: Llan-gors and Penally.

6.2. Figure-of-eight-shaped corn-dryer of fifth- or sixth-century date, Parc Cybi.

6.3. Later seventh- or eighth-century fish-trap, Oldbury flats.

7.1. Bone and antler combs.

191

199

211

227

7.2. South Hook, iron-smelting workshop. 229

7.3. Dinas Powys, fine-metalworking evidence.

232

7.4. Portrait of an armed man on the cross-slab at Llandyfaelog Fach. 240

7.5. Parts of the fragmentary Llangorse embroidered garment. 241

7.6. Penannular brooches. 242

7.7. Sites with imported pottery, glass, and other exotic finds in Wales and the borders, mid-fifth to early eighth centuries.

7.8. Discoveries of coins and silver/coin hoards in Wales dating from the late seventh to mid-eleventh centuries.

253

256

7.9. Balance weights from Llanbedrgoch. 259

7.10. The Llandwrog Hoard.

7.11. The Hywel Dda penny. 262

8.1. Early medieval ecclesiastical sites.

8.2. Distribution of early medieval cross-carved stones and stone sculpture.

8.3. Distribution of early medieval cemetery sites.

8.4. Llanmerewig Church, with its curvilinear embanked enclosure. 283

9.1. Votive offerings from Llys Awel, near Pen-y-Corddyn Mawr hillfort.

9.2. Rhuddgaer lead coffin.

9.3. The Llantrisant inscribed stone.

9.4. Early medieval ‘undeveloped’ cemeteries.

10.1. Llandough, showing the site of the modern church, the early medieval cemetery, and the Roman villa, with other burials nearby.

10.2. Bangor, showing the Cathedral and associated buildings, the probable line of the monastic enclosure, and other early medieval remains.

10.3. St Patrick’s Chapel, showing the eleventh- or twelfth-century building, with the rectangular burial enclosure beneath.

305

317

318

334

10.4. St Patrick’s Chapel, showing the eighth-century leacht during excavation in 2021. 334

10.5. Capel Maelog, showing evidence for the earlier settlement, the cemetery, the enclosure, and the late twelfth- or early thirteenth-century chapel.

11.1. Llaniestyn, early medieval cemetery and mortuary enclosure, and Pennant Melangell Church, with its eastern apse and the grave later associated with St Melangell.

11.2. The reliquary known as Arch Gwenfrewi, recorded by Edward Lhuyd at Gwytherin.

11.3. An iron bell from Llangenau and a copper-alloy bell from Llangwnnadl.

11.4. Tywyn cross-carved stone, with commemorative inscriptions in Old Welsh.

11.5. Disc-headed cross, Margam.

336

354

357

359

371

372

12.1. The Pillar of Eliseg.

381

12.2. Maen Achwyfan, with the figure of an armed warrior on the cross-shaft. 383

12.3. The polyfocal landscape of Bayvil in the cantref of Cemais.

12.4. Offa’s Dyke from the air.

12.5. Map showing Offa’s and Wat’s Dykes with other short dykes.

12.6. Evidence for the Viking impact on north-west Wales.

12.7. Evidence for Viking settlements in the vicinity of the Dee and Mersey estuaries.

385

388

390

400

404

12.8. Evidence for the Viking impact on south Wales. 406

Rediscovering the Early Medieval Past in Wales: Approaches and Sources

How did people live in early medieval Wales and how did their lives change over time?

The period c. ad 300–1050, spanning the collapse of Roman rule to the coming of the Normans, was formative in the development of Wales as an entity. At the end of the Roman period the colonial infrastructure based on military occupation, taxation, and a monetized market economy with mass-produced goods disintegrated and authority fragmented. Nevertheless, elements of Roman culture, including Latin literacy and Christianity, survived, and Latin- and ogham-inscribed stones testify to the rise of new elites, amongst them settlers from Ireland, and the establishment of small kingdoms. Although Roman settlements, such as forts, were largely abandoned, there is also increasing evidence for the continuation of long-established native ways of living. Hillforts and other high-status sites identifiable through craftworking and luxury imports became the homes of elites, who largely controlled the dissemination of wealth. However, the post-Roman centuries were also a period of climate deterioration leading to population decline and the need for agricultural adaptation. At the same time cemeteries and inscribed stones, later stone sculpture, and early church sites chart the course of conversion to Christianity, the rise of monasticism, and the increasing power of the Church. From the later seventh century onwards changes in both elite and farming settlements as well as the growing visibility of estates suggest societal change with indications of an expanding agricultural economy. However, the increasing wealth and power of Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, particularly Mercia, led to the loss of British lands to the east, and by the end of the eighth century the borders of Wales were being defined by the construction of Offa’s Dyke. Nevertheless, Anglo-Saxon pressure continued, especially in the north-east, and from the mid-ninth century onwards limited Hiberno-Scandinavian settlement was also taking place. Whilst raiding was undoubtedly destructive, external contacts also brought new opportunities for wider international trade and limited access to silver bullion and occasionally coin as means of exchange. Nonetheless, the economy remained underdeveloped compared with that of Ireland, England, and the Continent. At the same time continuing internal conflict is apparent and some kingdoms, notably Gwynedd in the north-west,

became more powerful, with the consequent need for mechanisms of control facilitated, for example, by places of assembly. Indeed, shortly before the advent of the Norman incursions, Wales was briefly united under the rulership of Gruffudd ap Llywelyn of Gwynedd.

Even though the early Middle Ages are seen as seminal in the evolution of Wales and the Welsh, there has been comparatively little analysis of the spectrum of archaeological evidence, and earlier studies have largely focused on a historical perspective.1 Apart from a brief period of attention in the 1960s and 1970s in the context of broader archaeological and historical studies of western and northern Britain, early medieval Wales has too often been an object of neglect. As far as the archaeology is concerned, this has arisen for a variety of reasons. The most important is the comparative lack of wealth in the material record and difficulties in locating early medieval sites in Wales, particularly in comparison with the archaeology of southern and eastern Anglo-Saxon England. This has tended to deflect attention elsewhere, even though the resource and the ways in which we can interrogate it continue to expand. Indeed, in Wales itself the focus has often been on the more visible remains from prehistory, the Roman period, and the later Middle Ages. More generally, the virtual purging by archaeologists of the Celts from the Iron Age and the ongoing debate about the origins of Celtic languages2 may have served to shift attention away from western and northern Britain in the early Middle Ages, in parts of which such languages continue to be spoken to this day. At the same time, the rise of World Archaeology as part of a broader global turn in the humanities, prompted by an emphasis on widespread developments and interconnections, may lead to the perception that the early medieval archaeology of Wales is at best regional, at worst an adjunct to that of Anglo-Saxon England, rather than part of a wider and more diverse Britain.3

The emphasis here is on using the archaeological evidence to try and reconstruct how people lived in the early Middle Ages in the land that became Wales, thereby enabling a better understanding of the factors that drove societal change over a period of more than seven hundred years. But although analysis of the material evidence has shaped my discussion, this is used as part of a multidisciplinary approach that also considers aspects of the written record and, where appropriate, linguistic evidence in the form of place names and personal names. By so doing, the aim is to enhance our understanding of a period for which the sources, archaeological and written, are frequently very patchy and challenging to interpret. Although historical figures, principally rulers such as Catamanus (Cadfan) of Gwynedd or Hywel Dda

1 The most important studies focusing on early medieval Wales are Lloyd 1911, Davies, W. 1982a, and Charles-Edwards 2013. All three, but particularly Davies, include some analysis of archaeological evidence. The only primarily archaeological general study is Arnold and Davies 2000.

2 For a key discussion of the ‘Celtic’ debate from an archaeological perspective, see Collis 2003, and, on linguistic research, see Sims-Williams 2020.

3 For recent consideration of Wales within a wider British context, see Fleming, R. 2010; Carver 2019.

(Hywel ‘the Good’), but also saints such as David, whose life has come down to us in the form of much later hagiography, are mentioned, my principal concern is with how the archaeological record and other sources can cast light on society more generally, ordinary people as well as the elite. It is also the intention as far as possible to place the evidence within a wider context, enabling comparison with other parts of Britain and Ireland and, where appropriate, with other parts of Europe in order to see broader trends, including the impacts of climatic, economic, and religious change.

This introductory chapter has two objectives. The first, focusing primarily on the material evidence, is to examine both earlier and more modern approaches to the study of the early medieval past in Wales. My aim is to introduce the evidence, the ways it has been studied, and the impact of these on how our understanding of it has developed over time. Discussion begins with antiquarian notices of Offa’s Dyke and the recording of inscribed stones and stone sculpture beginning in the sixteenth century, subjects that have continued to be major objects of interest until the present day. It ends with consideration of the growing archaeological resource resulting from both modern research and developer-led investigations and the increasing impact of scientific and other archaeological techniques at our disposal allowing a much broader and chronologically better-defined interpretation of the evidence to emerge. The second aim is to introduce the written sources concerned with early medieval Wales that are considered alongside the archaeological evidence elsewhere in this book. This includes an assessment of what has survived, before a chronological discussion of the main genres and some of the difficulties associated with using them. I also include consideration of some sources written beyond Wales that have relevant material and a number of later medieval sources that, if judiciously used, can shed some light on the early Middle Ages. I end with a brief assessment of research on place names.

ANTIQUARIANS AND THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF EARLY MEDIEVAL WALES

That Offa’s Dyke was the first early medieval monument in Wales to receive antiquarian attention is hardly surprising given its early mention in Asser’s Life of King Alfred 4 and the scale of the earthworks that still survive today. The earliest antiquarian description is by John Leland (c.1503–52), who visited Wales in the late 1530s and had clearly observed stretches of the dyke, which he termed a limes or fortified boundary.5 A century later his work undoubtedly influenced the polymath John Aubrey (1626–97),

4 Stevenson 1959, 12, ch. 14; Keynes and Lapidge 1983, 71.

5 Toulmin Smith 1906, viii–ix, 40; Ray and Bapty 2016, 57–8.

who had also seen the dyke and later wrote a short account of it in his unpublished Monumenta Britannica. 6

From the later sixteenth until well into the twentieth century, however, the study of the material remains of early medieval Wales was concentrated on the recording of stone monuments. These comprise memorial stones with commemorative Latin inscriptions and sometimes inscriptions in Primitive or Old Irish oghams, broadly datable between the fifth and mid-seventh centuries, and a range of Christian sculpture, notably large free-standing crosses with complex ornament and occasionally iconography as well as sometimes Latin inscriptions mainly datable to between the ninth and eleventh centuries. There are two main reasons for this. Firstly, the fact that these were substantial stone monuments gave them durability and meant that, when they were first noted, many still survived in the landscape or were rediscovered during nineteenthcentury church restorations. Secondly, those with inscriptions drew the attention of those seeking a way to understand their own national history, and their recording began as a small part of a much wider interest in the humanist recovery of the past centred in Italy, which was largely focused on classical remains, including sculpture and inscriptions.7 In Britain, however, it was also precipitated by the Reformation and dissolution of the monasteries, which placed many of these monuments in danger, a threat which increased during the mid-seventeenth century as a result of the destruction of the Civil War and subsequent neglect. This focused antiquarian efforts on recording what remained before even more was lost.8

The earliest references to the inscribed stones and stone crosses were made by both antiquaries with an interest in Wales who were based in London and by members of the local gentry. For example, William Camden (1551–1623),9 the famous chorographer and author of Britannia, visited Wales in 1590 and noted the Latin inscription on the stone at Clocaenog, Denbighshire,10 while George Owen of Henllys in north Pembrokeshire (c.1552–1613) was the first to mention the cross at Nevern.11 However, the earliest major advances in our knowledge and understanding of these monuments were made a century later by the Welsh antiquary, linguist, and natural scientist Edward Lhuyd (c.1660–1709), who became the second keeper of the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford.12 He knew Aubrey and became part of an intellectual circle at the vanguard of Anglo-Saxon studies,13 as a result of which he contributed the important Welsh additions to the new edition of Camden’s Britannia published

6 Scurr 2015, 184; Fowles and Legg 1980–2, iii, 884–5; Ray and Bapty 2016, 58.

7 Weiss 1969, which includes discussion of the study of classical inscriptions, 145–66; Barkan 1999, 17–18, 26–8; for the roots of nationalist history in the Renaissance, see Díaz-Andreu 2007, 31–4.

8 Parry 1995, 14. 9 Herendeen 2007.

10 Camden 1594, 519; Edwards 2013, 19, no. D1; for further early records of inscribed stones, see Redknap and Lewis 2007, 7.

11 Charles 1948, 270; Edwards 2007a, 12, no. P73; for further early records of sculpture, see Edwards 2013, 19.

12 Roberts 2022. 13 Edwards 2007b, 168.

F ig . 1.1. The inscribed stone at Llangadwaladr, Anglesey, commemorating King Catamanus (Cadfan) of Gwynedd (d. c.625), first recorded by Edward Lhuyd in 1699 (Crown copyright: Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales).

in 1695.14 Lhuyd carried out an immense amount of fieldwork in Wales and subsequently in other Celtic-speaking countries as well as having a wide range of correspondents. This enabled him to record a considerable number of archaeological sites and monuments of all periods, including nearly ninety early medieval inscribed and sculptured stones in Wales, which he often noted with remarkable accuracy.15 Equally, as a Welsh speaker, he developed a pioneering interest in Celtic philology, and the early medieval inscriptions with their British and Irish names were therefore clearly of interest to him. He recognized, for example, that the inscribed stone at Llangadwaladr, Anglesey, commemorating ‘Catamanus, wisest and most illustrious of all kings’ could be identified as King Cadfan of Gwynedd, who had died c.625 (Fig. 1.1).16

During the later eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries at the height of European Romanticism,17 Wales became a fashionable destination for travellers seeking to

14 Camden 1695, cols 583–678, with Lhuyd’s additions at the end of each county; Parry 1995, 347–54; Edwards 2007b, 180–1.

15 Edwards 2007b; 2010.

16 Edwards 2013, 21, no. AN26. The inscription reads Catamanus rex sapientisimus opinatisimus omnium regum

17 For the impact of Romanticism on the development of medieval archaeology, see Gerrard 2003, 23–9.

explore its picturesque scenery.18 As a result, tours of Wales were published drawing attention to early medieval stone monuments and other antiquities worthy of notice. The most influential was A Tour in Wales by Thomas Pennant (1726–98), the popular Flintshire travel writer and naturalist.19 For example, drawing on Lhuyd, he described and illustrated the ninth-century Pillar of Eliseg, Denbighshire, and mentioned the opening of the burial cairn on which it had once stood and its recent re-erection.20 He also visited other early medieval sites, such as the hillfort at Dinas Emrys and the monastery on Ynys Enlli (Bardsey Island), Caernarfonshire, giving lively accounts of the stories associated with them.21 Other tours include that of Pembrokeshire by Richard Fenton (1747–1821), who came from St Davids. He noted several carved stone monuments in the south-west, as well as ‘stone coffins’ at St Non’s Chapel, which are almost certainly early medieval graves.22 The artist and naturalist Edward Donovan (1768–1837) also toured south Wales and made fine illustrations of crosses at Llantwit Major and Margam, sometimes setting them within romantic landscapes.23

The next major breakthroughs in our understanding of early medieval Wales, its inscribed stones, and stone sculpture were fostered by the foundation of the journal Archaeologia Cambrensis in 1846 and, in the following year, the Cambrian Archaeological Association, which gradually placed the study of material remains in Wales on a more scientific footing.24 This should be seen as the Welsh expression of a similar expansion of interest in antiquarian societies in England and Ireland at this time alongside an increasing concern to preserve medieval remains from destruction.25 Members of the Association, some of whom had international contacts and included a number who lived outside Wales, met annually in different parts of the country. These meetings provided important opportunities to visit sites and monuments in a particular area and debate their significance as well as to deliver papers, many of which were published in the journal. During the mid- and later nineteenth century, four members stand out for their research on the early medieval inscribed and sculptured stones. Harry Longueville Jones (1806–70), co-founder of the Association and its journal, described and illustrated a considerable number of monuments, especially on Anglesey during the 1840s.26 Secondly, in 1846, J. O. Westwood (1805–93), later Hope Professor of Zoology at Oxford University and a scholar of early medieval Insular art, recognized for the first time the significance of the ogham inscription on the stone at Eglwys Nynnid, Glamorgan.27 He went on to compile Lapidarium

18 Andrews 1989, 39–66, 85–151. 19 Evans, R. P. 1991; Withers 2007; Edwards 2013, 21–2.

20 Pennant 1778–83, i, 399–401, pl. XXVI; Edwards 2013, no. D3.

21 Pennant 1778–83, ii, 182–4, 205–8.

22 Fenton 1903, 63, pl. opp. p. 353; Edwards 2007a, 13, 450.

23 Donovan 1805, i, 332–49, ii, 4–7, 24–7; Redknap and Lewis 2007, 13–15, figs 8–11.

24 Thomas 1978; Moore, D. 1998, 3–16; Edwards and Gould 2013, 144–9, 161–3.

25 Gerrard 2003, 30–55.

26 Edwards 2013, 22–4.

27 Ibid., 24–5; Westwood 1846; Redknap and Lewis, 2007, 16.

Walliae, the earliest illustrated catalogue of inscribed stones and stone sculpture in Wales, which included over 200 early medieval examples.28 Thirdly, from the 1870s, there was a revival of interest in Celtic philology led by John Rhys (1840–1915), an outstanding Welsh scholar with an international reputation, who in 1877 became the first Professor of Celtic at Jesus College, Oxford. Much of his research in Wales was focused on the early inscribed stones, especially those with oghams, and the forms of the personal names on them, though he also understood the importance of recording their contexts.29 Finally, the art historian and archaeologist J. Romilly Allen (1847–1907), now best known as the co-author of The Early Christian Monuments of Scotland, 30 also had connections with Pembrokeshire and was the first to analyse the form and ornament of the early medieval crosses in Wales.31

THE LATER NINETEENTH AND FIRST HALF OF THE TWENTIETH CENTURIES

The later nineteenth and first half of the twentieth centuries saw archaeology in Britain and Ireland gaining in significance as a discipline, and it is during this period that we can also identify several important developments in Wales which were to have a significant impact on our understanding of the early medieval period. These were set in motion by what has been termed a ‘National Awakening’, which focused above all on efforts to foster Welsh culture and education.32 The founding of the University of Wales in 1893 allowed the professional study of history in Wales for the first time, and in 1911 J. E. Lloyd (1861–1947), Professor of History at the University College of North Wales, Bangor, published A History of Wales from the Earliest Times to the Edwardian Conquest 33 This was a landmark since it sought to dispel the myths of the past and set the medieval history of Wales on a more scientific footing. Interestingly, in the book Lloyd not only demonstrates a deep knowledge of the Welsh landscape and its interaction with society but also tries to break down the barriers between historical and archaeological evidence,34 as, for example, in his discussion of the oghaminscribed stones as proof of Irish settlement during the fifth century.35

In Wales, however, there was no equivalent of the Victoria County History, established in England in 1899, or the English Place-Name Society founded in 1923.36

28 Westwood 1876–9; Redknap and Lewis 2007, 15–18; Edwards 2007a, 14.

29 Morris-Jones 1925; Sims-Williams 2019b; Edwards 2007a, 14–15.

30 Allen and Anderson 1903; Henderson 2004; Redknap and Lewis 2007, 21, fig. 16; Edwards 2013, 25.

31 Allen 1899.

33 Lloyd 1911.

32 Morgan 1981, 90–122; Pryce 2011, 4–6.

34 Pryce 2011, 95–113, 131–4. 35 Lloyd 1911, 111–21.

36 Gerrard 2003, 78–9. The first county history in Wales was Carmarthenshire, sponsored by the London Carmarthenshire Society, Lloyd 1935–9. Publication continues on a piecemeal basis. Cymdeithas Enwau Lleoedd Cymru (Welsh Place-Name Society) was founded in 2010.

Nevertheless, the foundation of three other Welsh institutions at this time undoubtedly championed the recording and preservation of the Welsh past and aided the development of archaeology in Wales, not least that of the early medieval period. The National Museum, centred in Cardiff, was finally set up after over half a century of struggle in 1907,37 and two exceptional archaeologists were early directors, Mortimer Wheeler (1924–6) and Cyril Fox (1926–48).38 The Museum provided an important focus for research and excavation as well as a repository for artefacts. The Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales was likewise established in 1908 to compile inventories of monuments county by county,39 and the University of Wales Board of Celtic Studies, which acted as a significant catalyst through initiating, funding, and publishing research within its remit, including archaeology, was inaugurated in 1919.40

The early volumes of the Royal Commission,41 apart from occasional speculation on possible early medieval sites, continued to record the only identifiable monuments known at that time: Offa’s and Wat’s Dykes,42 together with the inscribed stones and stone sculpture. However, they also emphasized the lack of knowledge of what was considered a formative period of Welsh history43 and the archaeology associated with it:

Perhaps the most difficult period that the Welsh antiquary has to deal with is that which lies between the departure of the Romans and the arrival of the Normans. From the archaeologists’ point of view this period extends for at least 700 years, and is in Wales the most barren of remains that may with fair assurance be attributed to it.44

Up to 1925 the volumes had been largely antiquarian compilations of earlier work and contained little original archaeological recording. However, when Pembrokeshire was published, it was roundly criticized and this resulted in new guidelines being adopted, proposed by Cyril Fox, which included the necessity for on-site survey and recording in the future and the need to employ professional archaeological staff.45 As a result, the Anglesey volume was of a very different standard. C. A. Ralegh Radford (1900–98), who was employed as Inspector of Ancient Monuments in Wales and

37 Morgan 2007; Mason, R. 2007, 23–9.

38 Hawkes 1982, 83–102; Carr 2012, 88–123; Scott-Fox 2002, 61–180.

39 Browne and Griffiths 2008, 19–24. Royal Commissions were established in England and Scotland the same year, Gerrard 2003, 79.

40 Pryce 2011, 73–6.

41 RCAHMW 1911–25, vols I–VII, covering Montgomeryshire, Flintshire, Radnorshire, Denbighshire, Carmarthenshire, Merionethshire, and Pembrokeshire.

42 RCAHMW 1912, xix. Wat’s Dyke was assumed to be the later and was mistakenly seen as a boundary between the English and the Danes.

43 RCAHMW 1921, xviii. 44 RCAHMW 1917, xxi.

45 Phillips 1987, 41; Browne 2007, 33–7.

Monmouthshire (1929–34)46 and then became a Commissioner, was responsible for the introduction to the early medieval period. He drew upon both written sources and archaeological evidence and showed a particular interest in the sites of what he termed the ‘Celtic Church’, suggesting, for example, that the remains on the island of Ynys Seiriol (Priestholm) were those of an early Christian hermitage. He also considered a small number of secular sites ascribed to the period, as well as cemeteries with stone-lined graves, finds, such as the Viking silver arm-rings from Dinorben quarry, and the full range of inscribed stones and stone sculpture. Where possible, he also attempted to place the monuments within a wider archaeological context, for example, for the first time, drawing attention to comparisons between some of the fifth- to seventh-century inscriptions and those in Gaul.47

Two other important projects were undertaken by the National Museum at this time, the second in partnership with the Board of Celtic Studies. In 1925 Cyril Fox (1882–1967) embarked upon his truly pioneering survey of the length of Offa’s Dyke together with Wat’s Dyke and the short dykes, completed in 1934, the foundation of all research since. To establish a detailed record of their extent, features, and condition, he systematically walked the dykes describing the remains and annotating the 6-inch Ordnance Survey map, as well as drawing profiles and taking photographs. Fieldwork was published annually and the results subsequently analysed, being finally brought together in 1955.48 Secondly, during the 1930s V. E. Nash-Williams (1897–1955), Keeper of Archaeology at the National Museum, embarked on research to catalogue and classify the inscribed stones and stone sculpture, which by now comprised over 400 monuments, though its highly influential publication was not achieved until after the Second World War.49

In England, pagan and conversion-period Anglo-Saxon graves had long attracted antiquarian attention, including excavation, because of the presence of mounds, cremation urns, and often rich grave goods, and their early medieval date was first recognized in the late eighteenth century.50 The first Anglo-Saxon settlements, notably Sutton Courtenay, Oxfordshire, were identified in the early twentieth century, though similar remains at the time were long interpreted to indicate miserable living conditions.51 By contrast, in Wales there were almost no excavations of sites ascribed to the early medieval period during the later nineteenth and first half of the twentieth centuries. This was because a lack of diagnostic artefacts made them almost impossible to identify unless they were mentioned in the written sources. Nonetheless, Llangorse crannog, Breconshire, provides an interesting early exception. Its discovery by Edgar

46 Gilchrist 2013, 343. 47 Radford 1937; Edwards 2007a, 25–6.

48 Fox, C. 1955; Ray and Bapty 2016, 68–77.

49 Nash-Williams 1950; Randall 1956; Redknap and Lewis 2007, 22–3; Edwards 2013, 26–8.

50 Kendrick and Hawkes 1932, 307–20; Lucy 2000, 5–14; Williams, Howard 2006, 5–6.

51 Kendrick and Hawkes 1932, 320–4; Hamerow 2012, 7–8.