List of Illustrations

0.1 The Indian Emperor. Or the Conquest of Mexico. As performed in the year 1731 in Mr Conduitt’s, Master of the Mint, before the Duke of Cumberland &c. Act 4, Scene 4; William Hogarth, 1732

0.2 Sir Isaac Newton; Godfrey Kneller, 1702

1.1 Newton’s House, 35 St Martin’s Street; C. Lacy after Edward Meredith, 1811

1.2 David Le Marchand; Joseph Highmore, 1724

2.1 Tower of London; Samuel and Nathaniel Buck, 1737

2.2 Queen Anne’s coronation medal; Isaac Newton and John Croker, 1702

3.1 Family tree; Isaac Newton, 1705

4.1 Medal of John Conduitt; designed by Gravelot, engraved by John Sigismund Tanner, 1737

5.1 Title page, The Constitutions of the Free-Masons; James Anderson, 1723

5.2 Frontispiece, The Constitutions of the Free-Masons, 1723; engraving by John Pine

5.3 A New & Exact Map of the Coast, Countries and Islands within ye Limits of ye South Sea Company; Herman Moll, 1711

6.1 Principia Mathematica (1713) with handwritten additions and corrections; Isaac Newton, after 1713

6.2 Frontispiece of Principia Mathematica (1726); George Vertue after John Vanderbank, 1726 122

7.1 Caroline Wilhelmina of Brandenburg-Ansbach; Jacopo Amigoni, 1735

8.1 ‘The Art of Coining’, Universal Magazine, 1750

8.2 Gold assay plate, 1707

9.1 Africa: Corrected from the Observations of the Royal Society at London and Paris; John Senex, 1725 173

9.2 Company of Royal Adventurers Trading into Africa, coat of arms, 1663

9.3 Ivory imported by the Royal African Company, 17th or 18th century 189

9.4 Cape Coast Castle 192

10.1 Newton in Senegal, 1770; from Jean Delisle de Sales, Philosophie de la nature, 1770

The first of all English games is making money. That is an all-absorbing game; and we knock each other down oftener in playing at that, than at football, or any other roughest sport: and it is absolutely without purpose; no one who engages heartily in that game ever knows why. Ask a great money-maker what he wants to do with his money,—he never knows. He doesn’t make it to do anything with it. He gets it only that he may get it. ‘What will you make of what you have got?’ you ask. ‘Well, I’ll get more,’ he says. Just as, at cricket, you get more runs. There’s no use in the runs, but to get more of them than other people is the game. And there’s no use in the money, but to have more of it than other people is the game.

John Ruskin, The Crown of Wild Olive, 1866

Prologue

This book has two subjects: Isaac Newton’s three decades in London, and a picture by William Hogarth that is packed with Newtonian references.

Figure 0.1 The Indian Emperor. Or the Conquest of Mexico. As performed in the year 1731 in Mr Conduitt’s, Master of the Mint, before the Duke of Cumberland &c. Act 4, Scene 4; William Hogarth, 1732

Prologue

Here are ten facts about Isaac Newton.

Some of them may surprise you.

All of them are discussed in this book.

He owned two silver chamber pots, twelve bibles, and thirteen copies of the New Testament.

He lost a small fortune on the stock market by buying high and selling low.

He lived in London longer than in Cambridge.

He was twice elected MP for Cambridge University.

He was paid a bonus for every coin minted from slavetrade gold.

He had sworn to sexual abstinence, but was plagued by obsessive thoughts.

He wanted to ban imports of luxury goods from China and India.

He worked for many years in the Tower of London while it still housed a zoo.

He hired an experimental assistant who became the Grand Master of English Freemasonry.

He believed that 666 is the Number of the Name of the Beast.

Precise figures are hard to find, but this table indicates Newton’s relative affluence by listing estimates for the wealth at death of twelve other people who appear in this book.1

£1000 in 1700 was worth approximately £140,000 in 2018 using measures of price, and £2,500,000 using measures of income.2

Hans Sloane

David Garrick

Isaac Newton

Edward Gibbon

George Handel

Physician and collector

Actor

Master of the Royal Mint

Historian

Composer

Robert Boyle Chemist

Alexander Pope Poet

Samuel Johnson

Writer

John Flamsteed Astronomer Royal

Elizabeth Tollet Poet

William Whiston

Daniel Defoe

John Desaguliers

Former Cambridge professor

£100,000

£100,000

£32,000

£26,000

£17,500

£10,000

£5000–6000

£2300

£2000

£1770+

£1300+

Author Nothing

Master of Freemasonry Pauper

To say that all the world’s a stage had become a cliché long before William Shakespeare was born.3 During the eighteenth century, members of England’s elite put on their own daily performances. Their elaborate gestures, powdered wigs, tightly drawn-in waists and elliptical phraseology all helped to disguise a personal identity that remained closed off even from husbands and wives. Emotions were to be reined in, not displayed publicly. Born with life-scripts marked up in advance, privileged children were moulded into their adult roles, their futures mapped out in front of them. Posing for family portraits, miniature aristocrats held stiff, formal poses, perhaps clutching a little sword or wearing a dress cut so low that a nipple showed. One major priority for landed families was to preserve their estates intact, and so the oldest son inherited everything; daughters remained the possession of their father until marriage, when they—along with everything they owned—became the property of their husband.

London polite society thrived on financial schemes, sexual intrigues, and political manoeuvres, and it became fashionable for children to perform adult plays that taught them about the survival skills they would need. In 1731, four years after Newton died, the Drury Lane Theatre revived John Dryden’s The Indian Emperour, which had first

been staged in 1665, when Newton was at Cambridge. Soon afterwards, the manager’s son—actor and notorious rake Theophilus Cibber—directed a children’s performance in the house of John Conduitt, Newton’s successor as Master of the Mint. The wealthy audience included the juvenile actors’ proud relatives as well as three royal children—Prince William (already the Duke of Cumberland, despite his youth) and his two younger sisters. William must have enjoyed the occasion because, at his request, the play was presented again the following year for their parents—King George II and Queen Caroline—at St James’s Palace.4

Now largely forgotten, Conduitt was a man of considerable standing, a Member of Parliament and husband of Newton’s half-niece. An assiduous social climber, he was proud of the aristocratic entertainment he had provided, and he wanted a permanent record. By the following year, his friends were gossiping that he was ‘going to have a conversation piece drawn by Hogarth, of the young people of quality that acted at his house; and if I am not mistaken he hopes to have the honour of the Royal part of the audience in the picture.’5 He did indeed commission Hogarth to portray this event in an exceptionally large picture, 130 × 145 cm (Figure 0.1). Because it contained so many individual faces, the painting took three years to finish. This domestic scene is still privately owned, and unlike much of Hogarth’s work, was not on sale as an engraving until 1791, long after most of its participants had died.

Conduitt made an astute choice of artist. Hogarth is now most famous for his scenes of depravity and corruption, which forced prosperous purchasers to confront the risks of slipping from their comfortable existence to share the misery of London’s gin-sodden slum dwellers. But at the time, he was renowned for his conversation pieces. The word ‘conversation’ carried implicit connotations of sexual as well as verbal encounters, and these carefully constructed group pictures depicted long-term tensions and ambiguities in eighteenth-century culture. Resembling snap-shots in oils of a specific instant in time, they portrayed the wealthy at leisure inside their own homes, displayed on canvas as if participating in a performance.

Conduitt’s commission arrived with perfect timing, while Hogarth was beginning to enjoy the success of his Harlot’s Progress series.

After celebrating with friends on a trip to Kent, he set to work. Dryden’s The Indian Emperour. Or the Conquest of Mexico was loosely based on the Spanish colonization of the Aztecs in the early sixteenth century. Hogarth had recently painted another play, the theatrical hit The Beggar’s Opera, when he sat among the Drury Lane audience sketching on blue paper to remain concealed in the dark. Perhaps remembering the five years his father had spent in Fleet Prison, Hogarth depicted a grim scene inside a cell, featuring two women and a man in handcuffs. In five successive versions, he increasingly included the audience as well as the action on stage, so that in retrospect the series seems to have been leading up to a grand finale—his Indian Emperor.

Again, he showed a prison scene, when two local princesses are vying for the love of Hernán Cortés, a Spanish invader who has been temporarily imprisoned by Montezuma, an Aztec emperor. The adults in the audience would have known that, before the evening was over, Montezuma would die and the Cortés character would emerge as conqueror, but perhaps for the watching children the plot and its savagery came as a surprise.

Hogarth’s pictures were rarely unambiguous: he liked stacking them with symbolic references and double meanings. Here shimmering flashes of gold and cream evoke power and aristocracy both on and off the makeshift stage, while the scene ripples with concealed passions. By lacing it with visual references to Newton, Hogarth simultaneously paid tribute to an English icon and emphasized Conduitt’s high status in London society.

Physically present as a marble bust surveying the scene from the mantelpiece, Newton also pervades the canvas metaphorically. In the audience, the royal governess is bidding one of her daughters to pick up the fan that has fallen though the force of gravity, while the prompter at the back left is one of Newton’s staunchest propagandists. Appropriately enough for an intellectual Titan, only Newton’s head is present, glowing like a floodlit reminder of his innovative book on optics. Materially absent from the room as from life, Newton’s mind is dominant. Resembling gravitational forces that shoot through empty space, he is both nowhere and everywhere, an all-seeing divine presence looming over these childish human activities.

When Isaac Newton wanted something, he was willing to pay for the best—and he knew that whatever a person’s inner virtues, outward appearances counted. England was renowned as the land of portrait painters and, like other affluent social climbers, Newton commissioned London’s top artists to create flattering pictures for winning over his critics and influencing his supporters. This was common practice in England; in contrast, continental Europeans looked down with disdain on such ‘FacePainting’, regarding it as inferior to history painting, which showed a specific event such as a famous battle or a mythological scenario. Newton hung many of his portraits in his own home, where his visitors could admire the exclusive good taste that can only be purchased by the wealthy. When he became president of London’s Royal Society, one of his first steps was to organize a picture collection of its eminent Fellows. To set a suitable example, Newton donated a large picture of himself, making sure that everyone recognized his elite status by adorning it with gold lettering (in Latin) advertising his role as president.

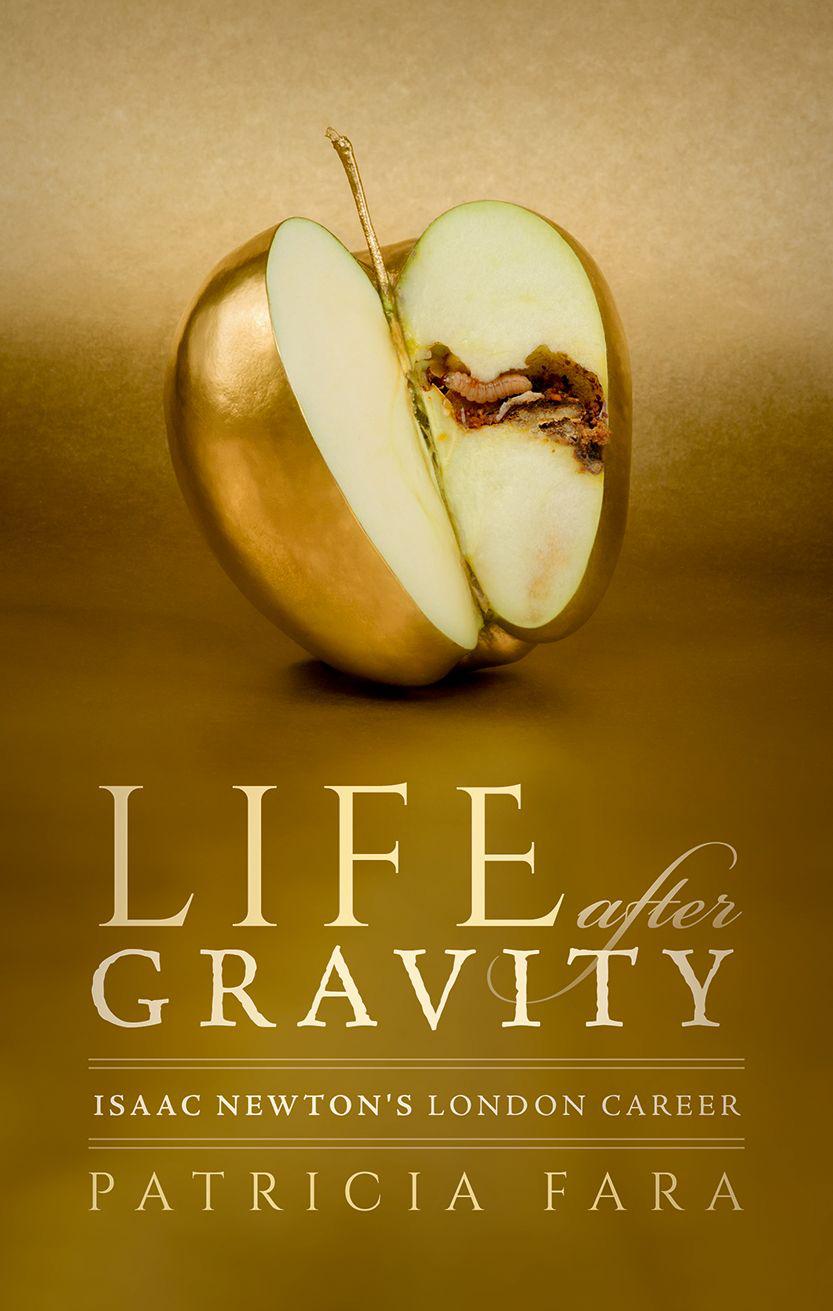

Among Newton’s favourite artists was the Germanborn Godfrey Kneller, who had studied under Rembrandt van Rijn in Amsterdam before being appointed Principal Painter to the Crown by Charles II. Many years later, when one of Newton’s London homes was demolished, Kneller’s card was found underneath the floorboards. He painted five different portraits of Newton, although only two of them are well known. Newton’s facial characteristics are similar in all of them, and their striking differences are due not to his advancing age but to his desire of repeatedly presenting himself in different roles.

The first time he sat for Kneller, in 1689, Newton was in his midforties and had published the Principia—his famous book on mechanics and gravity—just two years earlier. (In English, this book’s full title is Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy; because all three editions were published in Latin, it is usually referred to as the Principia, short for Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica). This early portrait shows him as a reclusive academic with unkempt hair and a thin pale face, a dedicated scholar who has temporarily ventured out of solitude before scurrying back to the security of his

rooms. It has often been interpreted to confirm what many people want to believe: that Newton was an unsullied scientific genius who disdained all thoughts of material comfort. Although that persona dominates biographies and documentaries, after arriving in London Newton radically refashioned himself, and the sombre picture remained virtually unknown, languishing in the dark corridor of a country mansion until the middle of the nineteenth century.6

Kneller’s second portrait (Figure 0.2) was very different, and it displays the manabouttown who is the less familiar subject of this book—the metropolitan Newton who thrived in high society

Figure 0.2 Sir Isaac Newton; Godfrey Kneller, 1702

for three decades and became extremely rich. When it was painted in 1702, Newton was already Master of the Mint, and within three years he had become President of the Royal Society and been knighted by Queen Anne. More conventional but less intimate than the first, the painting shows a distinguished gentleman wearing a fine white shirt and gazing out arrogantly at the viewer. This Newton appears determined to advertise his elegant worldly status. The glossiness of his wig competes with the sheen of the sumptuous velvet wrap, which is deep crimson, the colour of nobility that remained Newton’s favourite. Unlike the previous portrait of 1689, this one was widely circulated. As well as being repeatedly copied in oils, it was engraved in black and white with varying degrees of fidelity. Reproduced in books, prints, and medallions, this version travelled all over Europe and became the standard Enlightenment image of Sir Isaac Newton, Britain’s most distinguished natural philosopher.

Perhaps on Kneller’s advice, in this second picture Newton’s face is surrounded by luxuriant but artificial auburn locks, very similar to the style worn by King George I when he posed for Kneller’s coronation portrait. Men’s wigs were not mere decoration: they indicated the owner’s station in life. Unlike those worn by women, which supplemented their natural hair, men’s were a coverover or even a total replacement: older men might be naturally bald, while younger ones could have their heads shaved. In 1720, an advice manual on hair and teeth made it clear that whereas women chose such adornments to make themselves more beautiful, ‘men should dress suitable to their various ranks in life, whether as a magistrate, statesman, warrior, man of pleasure, &c.’ Just like theatre actors who change their costume, the author explained, male social performers ‘may be dress’d to produce in us different ideas of the qualities of men’.7 In Kneller’s portrait, Newton is acting out the cosmopolitan role that he assumed in 1696, after terminating over three decades of scholarship at Cambridge to live in London for the rest of his life.

This book explores how Newton interacted with elite metropolitan society, a milieu far removed from his previous surroundings of the remote Lincolnshire countryside and the secluded cloisters of Trinity College. He spent the next thirty years running London’s Royal Mint, revamping the British economy and moving in

fashionable aristocratic circles—a very different character from his previous persona as a reclusive Cambridge academic. Rather than soaring above mundane concerns, this Newton immersed himself in financial negotiations, court intrigues, and international politics. By the time he died, he had revived the ebbing fortunes of the Royal Society, but he had also accumulated a substantial fortune, been knighted by Queen Anne, and launched the international gold standard. As a wealthy Enlightenment gentleman with influential contacts, Newton played a key role in the interlinked growth of science, the state, and British global trade.

Preparing to Leave

This was no overnight metamorphosis. Newton finally abandoned Cambridge in the spring of 1696, but he had been exploring future possibilities for some time, prompted by the publication of the Principia in 1687 and the political upheaval of the Glorious Revolution the following year. Each time he tried but failed to get a better position, the metropolis became increasingly attractive. By then, he had already emerged from the sanctuary of his books and experiments to become prominent in university politics. Over the next few years, he often travelled to London, even living there for months at a time. During this transitional period, he established fresh friendships and prepared himself for a fresh future.

Even during his most reclusive years, Newton could never totally isolate himself from Cambridge’s intertwined religious and political intrigues: survival demanded tactical secrecy and flexibility. He openly abhorred Catholicism openly, denouncing it as a false religion that posed a dangerous threat to the English nation. In contrast, he kept selfprotectively quiet about his aversion to some doctrines of the Anglican Church, subscribing instead to a religious heresy named after Arius, a Christian living in Egypt around the end of the third century. The Arian doctrine maintained that although Jesus Christ was the Son of God, he was born later and was therefore secondary. This conflicted with the Trinitarian creed of the Anglican Church that God comprises three distinct but divine personages: God the Father, God the Son, and God the Holy Spirit.8

When Newton was offered a position as Cambridge’s second Lucasian Professor of Mathematics, his Arianism presented an awkward obstacle, because Charles II had decreed that in addition to their vow of celibacy, all university fellows should subscribe to the ThirtyNine Articles, the basic statement of Anglican beliefs. Newton’s manuscripts reveal how much he struggled to observe sexual abstinence, but at least it was in line with his own high moral standards. The new requirement presented a greater challenge: even the name of his Cambridge college must have felt alien for a heretic who rejected the validity of the Holy Trinity. Technically, it was possible to obtain a royal dispensation, but several requests had already been rejected. Somehow, although it is still not clear how, Newton managed to wriggle out of the university stipulation for orthodoxy. Mysteriously, after a visit to London, a draft exemption was on its way to the Attorney General. Somebody somewhere— probably his predecessor in the post, Isaac Barrow—had pulled strings. From then on, no Lucasian Professor was obliged to take the oath of Anglicanism. Even so, discretion was essential. While Newton diplomatically kept quiet about his unorthodox beliefs, his successor William Whiston actively advertised his own Arianism, and was soon dismissed from the university in disgrace.

Consumed by his work, and keeping well below the parapet, Newton effectively disappeared from public view. When he was at last nearing the end of the Principia, Newton embarked on a new phase in his life, gradually emerging from his selfimposed seclusion. By then, James II had inherited the throne from his brother, Charles II—and James was determined to make England Catholic. Refusing to heed his advisers, he replaced Anglicans in powerful positions by Catholics, despotic behaviour that aroused great resentment across the country. Even his daughters, Anne and Mary, complained that ‘the priests have so much power with the King as to make him do things so directly against the Laws of the Land, & indeed contrary to his own promises.’9

At Oxford and Cambridge, James began distributing dispensations for Catholics, who were normally banned from the universities. In the spring of 1687, Cambridge University rebelled by making a test case out of a Benedictine monk, Alban Francis, refusing to follow

James’s instructions that this ardent Catholic should receive a degree without swearing allegiance to the ThirtyNine Articles. Angry letters circulated; secret meetings were convened. Hypocrisy does not seem too strong a word for describing Newton’s behaviour as he launched himself into the campaign against Francis. The Arian who ten years earlier had refused to take vows himself now defended the Anglican Church, insisting that Francis should not be admitted without signing up to the ThirtyNine Articles. Newton did have other options: he might have left Cambridge, or he could have kept quiet about his conviction that James had no right to intervene in academic affairs. Instead, he decided that protecting the university against Catholicism and Stuart control was more important.

Agitating when appropriate, but discreetly absenting himself from Cambridge when expedient, Newton became such a key player that he was one of eight representatives chosen to defend the university at an official hearing in London presided over by George Jeffreys, a sycophantic supporter of King James. Already notorious as ‘The Hanging Judge’, Jeffreys ruthlessly enforced royal policy and was duly rewarded with repeated promotion. For his part, Newton drafted fervent defences of the university’s position and rose to prominence. Although details of the negotiations remain murky, the outcome is clear: Newton’s side won, sustaining only one casualty, an incompetent vicechancellor with a drink problem.

By the end of 1688, William of Orange—Protestant husband of James’s daughter Mary—had landed in England and seized power. James had fled to France, his Catholic protégés had been forced out of Cambridge, and Jeffreys was confined in the Tower (reportedly, he had been captured in a Wapping pub, despite having shaved off his eyebrows and disguised himself as a sailor). Conspirators tend to be scrupulous about covering their tracks, and it is now impossible to retrieve definite information about Newton’s possible involvement in the clandestine discussions that had been taking place all over the country. Even so, stray references make it clear that Newton had powerful patrons who were ready to reward him for past favours—so much took place behind the scenes, so much was hinted at rather than openly stated. Whatever had been happening, Newton rapidly emerged as a powerful figure within the