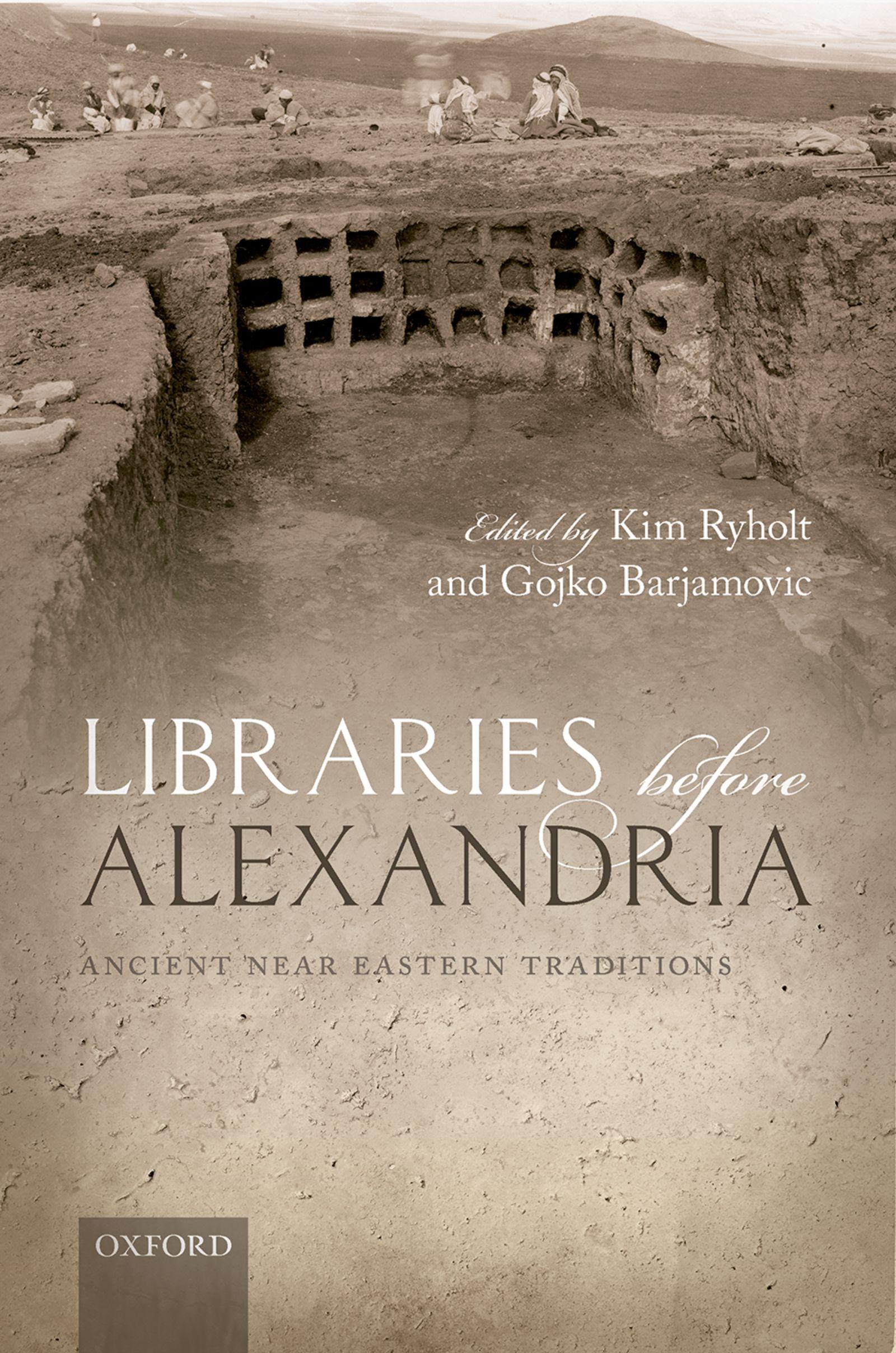

Librariesbefore Alexandria

AncientNearEasternTraditions

Editedby KIMRYHOLT and

GOJKOBARJAMOVIC

GreatClarendonStreet,Oxford,OX26DP, UnitedKingdom

OxfordUniversityPressisadepartmentoftheUniversityofOxford. ItfurtherstheUniversity’sobjectiveofexcellenceinresearch,scholarship, andeducationbypublishingworldwide.Oxfordisaregisteredtrademarkof OxfordUniversityPressintheUKandincertainothercountries

©OxfordUniversityPress2019

Themoralrightsoftheauthorshavebeenasserted

FirstEditionpublishedin2019

Impression:1

Allrightsreserved.Nopartofthispublicationmaybereproduced,storedin aretrievalsystem,ortransmitted,inanyformorbyanymeans,withoutthe priorpermissioninwritingofOxfordUniversityPress,orasexpresslypermitted bylaw,bylicenceorundertermsagreedwiththeappropriatereprographics rightsorganization.Enquiriesconcerningreproductionoutsidethescopeofthe aboveshouldbesenttotheRightsDepartment,OxfordUniversityPress,atthe addressabove

Youmustnotcirculatethisworkinanyotherform andyoumustimposethissameconditiononanyacquirer

PublishedintheUnitedStatesofAmericabyOxfordUniversityPress 198MadisonAvenue,NewYork,NY10016,UnitedStatesofAmerica

BritishLibraryCataloguinginPublicationData Dataavailable

LibraryofCongressControlNumber:2019952282

ISBN978–0–19–965535–9

DOI:10.1093/oso/9780199655359.003.0001

Printedandboundby

CPIGroup(UK)Ltd,Croydon,CR04YY

LinkstothirdpartywebsitesareprovidedbyOxfordingoodfaithand forinformationonly.Oxforddisclaimsanyresponsibilityforthematerials containedinanythirdpartywebsitereferencedinthiswork.

Preface

Thisbookisconceivedasanintroductionandreferencetolibrariesinthe pre-ClassicalworldofEgyptandWesternAsia.Itoriginatedfromourconvictionthatacollectedpresentation,writtenbyspecialists,waslongoverdue, asoutlinedinChapter1.The finalproducthasbeenmuchtoolonginthe making.Almostadecadehaspassedfromthe firstmeetingandthelively debatesoftheauthorsinDenmark.Wearegratefultothecontributorsfor theirpatienceandfortheirwillingnesstokeeptheeditorialprocessgoingover suchalongperiodoftime.

Theprojectonlibrariesinthepre-ClassicalEgyptandWesternAsiawhich ledtothisbookwasthe firstofaseriesoflargecollaborativeeffortsinitiatedby the CenterforCanonandIdentityFormationintheEarliestLiterateSocieties undertheUniversityofCopenhagenProgrammeofExcellencedirectedby KimRyholtandwithGojkoBarjamovicasitsAssociateDirector.Weoweour gratitudetotheRectoroftheUniversityofCopenhagenforfundingthe researchcenterovera five-yearperiod2008–2013.

Throughoutourwork,wehavereliedonthegenerosityofmanycolleagues andfriends,withwhomwehavebeenprivilegedtohavestimulatingdiscussionsandmuchhelpandadvice.Thisincludesthesixteencolleagueswho graciouslytookouttimetoserveasanonymousreadersofthetenchaptersin thisbook.Wearealsoindebtedtonumerousfriendsandcolleaguesworking inarchives,onexcavations,andinmuseumcollections,forkindlyproviding valuableimagesandplansusedthroughoutthisvolume.

Inparticular,wearegratefultoHaiderAlmamori,AdelalTai,andKhalidal Timimifortheirkindpermissiontopublishacompleteimageofthemagnificent E’ulmashlibraryforthe firsttime(Fig.1.10),toKlausWagensonnerforproviding imagesandhisowndrawingsfromtheYaleBabylonianCollectionforthe introductorychapter(Figs1.5,1.6,1.9),toFikriKulakoğluforsharinghis unpublishedexcavationphoto(Fig.1.8),toAndreasSchachnerforproviding high-resolutionplansofHattusa(Figs5.1–5.3),toSaadEskanderforhisimage fromKalhu(Fig.8.2),toFelixArnoldfortheplanofthetowerhouseat Elephantine(Fig.10.3),toMartinAndreasStadlerforthephotographofthe templelibraryatEdfu(Fig.10.4),toLuigiPradaforthephotographoftheostraca jarsatNarmuthis(Fig.10.12),andtoJeffreyC.BlossomoftheHarvardCenterfor GeographicAnalysisforproducingthemainmapforthevolume(pp.xviii–xix).

WearealsogratefultoSerainaNettwhoprovidedtheinitialtranslationof Chapter5fromGerman;toPaulKosminforvaluablecommentsandcriticism; totheremarkableworkofTimothyR.Beck(UniversityofMinnesota)during thecopy-editingphaseofthemanuscript;andnotleasttoGeorginaLeighton, KalpanaSagayanathan,SeemadeviSekarandtheOxfordUniversityPressfor their flexibilityandsupportinproducingthisvolume.

Contents

ListofMapandFigures ix

ListofTables xv

ListofContributors xvii

1.LibrariesbeforeAlexandria 1 KimRyholtandGojkoBarjamovic

2.TheRiseofLibrariesinWesternAsia, c.2600–2300

KamranVincentZand

3.LibrariesinAncientEgypt, c.2600–1600

R.B.Parkinson

4.ArchivesandLibrariesintheOldBabylonianPeriod, c.1900–

PaulDelnero

5.TheTabletCollectionsoftheHittiteState, c.1650–1080

PaolaDardano

6.LibrariesinSyriaandtheLevantintheLateBronzeAge, c.1450–1100

MatthewRutz

7.LibrariesinAncientEgypt, c.1600–800

FredrikHagen

8.ScholarlyTabletCollectionsinFirst-MillenniumAssyria andBabylonia, c.700–200

EleanorRobsonandKathrynStevens

9.Assurbanipal’sLibrary:AnOverview

IrvingFinkel

10.LibrariesfromLatePeriodandGraeco-RomanEgypt, c.800

KimRyholt

ListofMapandFigures

Map

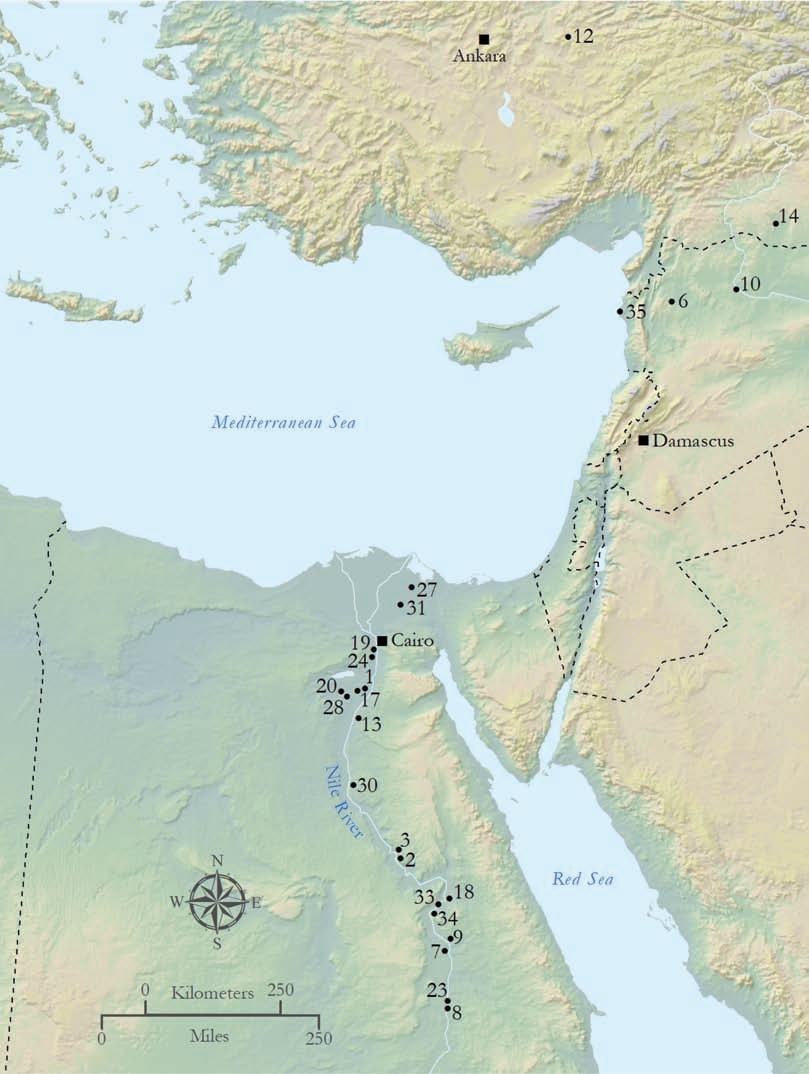

1.MapofEgyptandWesternAsiashowingthelocationoflibraries andassemblagesofliterarymanuscriptsdiscussedinthebook xviii

Figures

1.1.EgyptianscribalstatueofahighofficialfromtheKushiteperiod, lateeighthcentury

1.2.Papyriwithsamplesofdifferentscripts

11

ImagescourtesyofthePapyrusCarlsbergCollection 13

1.3.Ostracawithsamplesofdifferentscripts (a)ImagecourtesyoftheNationalMuseumofDenmark (bandc)ImagescourtesyofthePapyrusHauniensis Collection 14

1.4.Egyptianscribalpaletteofwoodwithreedpens ©TrusteesoftheBritishMuseum 17

1.5.Brokencuneiformtabletsthatshowhowobjectswereprepared forwriting

PhotosbyK.WagensonnerandcourtesyoftheYaleBabylonian Collection 18

1.6.Differenttablettypesandformatsthroughhistory

Tabletsa–b:photosbyK.WagensonnerandcourtesyoftheYale BabylonianCollection.Writingboard:photocourtesyofthe MetropolitanMuseumofArt,NewYork 20

1.7.Examplesofre-usedpapyri

ImagescourtesyofthePapyrusCarlsbergCollection 23

1.8.Claytablet,stillintheground,excavatedin2009byProf.Kulakoğlu andhisteamfromAnkaraUniversityatthesiteofKültepeinTurkey PhotobyFikriKulakoğluandcourtesyoftheKültepeExcavations24

1.9.Tabletsbearingcolophonsforidentificationorcollectionprovenience PhotosanddrawingsbyK.WagensonnerandcourtesyoftheYale BabylonianCollection 29

1.10.ThetemplelibraryofE’ulmashinSippar,excavatedbyIraqi archaeologistsin1988 PhotobyAdelalTai1988,photoeditbyKhalidalTimimi2018 Usedwiththeircourtesyandkindpermission 47

2.1.PlanofexcavationsinthecityofShuruppag(modernFara)around theso-called ‘TabletHouse’ atXVhandtheadjacentareaNorthofXVh AfterMartin1988:161 75

2.2.PlanofhouseIXacandtheareaoftheIXaatablets AfterMartin1988:162 77

2.3.PlanofTellAbuSalabikharoundAreaE(theBurnedBuilding andSouthernUnit)andtheEasternHouses AfterKrebernikandPostgate2009:2 81

2.4.PlanofPalaceatEbla(modernTellMardikh)with findspotsofthe smallergroupsmarkedasA–BandD–E,andthepositionoftheMain ArchivemarkedasC AfterArchi2015:78 85

2.5.(a)PlanoftheroomthatcontainedthemainarchiveC(L2769) inPalaceGatEbla,and(b)aschematicoverviewofitsoriginal organizationasdeterminedbytheItalianexcavators AfterArchi2015:82–388

2.6.(a)Imageofthelexicaltabletsasfoundinheapsfromthecollapsed shelvesalongthenorthernwall,and(b)thenorthernsectorofthe easternwallofL2769inPalaceGatEbla AfterMatthiae1986:63–589

3.1.Thename ‘Amenemhat’ inthedifferenttypesofscriptinuse intheMiddleKingdom

DrawingbyR.B.Parkinson 118

3.2.Afunerarymodelofascribe’schestwiththelidopen,showingrolls laidoutlengthwaysandhorizontally ©TrusteesoftheBritishMuseum 121

3.3.AMiddleKingdomstoragebox,similartothatinwhichthe ‘Ramesseum papyri’ werediscovered ©TrusteesoftheBritishMuseum 122

3.4.ApapyrusfromthearchiveofNeferirkareatAbusir,withdutyrosters laidoutintablesonruledguide-linesonafull-heightroll ©TrusteesoftheBritishMuseum 125

3.5.Fourrollsdepositedonlidofacoffininanearly12thDynastyburial chamber:P.ReisnerI–IVasdiscoveredinTombN408/406at Nagael-Deir

AfterW.K.Simpson1963a:[frontispiece].Photographcourtesy ofMuseumofFineArt,Boston 145

3.6.Ahalf-heightrollwith TheTaleofthePeasant (B1146–166)written inliteraryhieraticinamixtureofverticalandhorizontalformats CourtesyoftheÄgyptischesMuseumundPapyrussammlung,Berlin149

3.7.P.Ramesseum6with HymnstoSobek (l.40–58) ©TrusteesoftheBritishMuseum153

4.1.Left:planofthecityofUrdrawnbyF.Ghiowithnumbersremoved (CreativeCommonsLicense3.0).Middle:PlanofUrneighborhood areaAH.AfterC.E.WoolleyandM.E.L.Mallowan,TheOld BabylonianPeriod,UrExcavations7[London:BritishMuseum,1976], fig.124.Right:PlanofNo.1BroadStreet,drawnbyauthor. ImagecourtesyofMcGuireGibsonandtheOrientalInstituteofthe UniversityofChicago175

4.2.Left:GeneralplanofthecityofNippurwiththelocationof ‘HouseF’ markedinthelowerrightcornerof ‘TrenchA’ 172.Imagecourtesy ofMcGuireGibsonandtheOrientalInstituteoftheUniversityof Chicago.Right:CompositeexcavationplanofHouseF,Level10 redrawnafterRobson2001.

ImagecourtesyofFabrizioGhio(ResearchGate)andthePenn MuseumUrDigitizationProject 180

5.1.GeneralplanofHattusa,thecapitaloftheHittiteState ImagecourtesyofAndreasSchachner 194

5.2.PlanofBüyükkale,theroyalcitadelofthecapitalHattusawithan outlineofthemainpalatialbuildingsandfortifications

ImagecourtesyofAndreasSchachner 195

5.3.PlanoftheGreatTemple(alsoknownasTemple1)atHattusawith surroundingstorehouses

ImagecourtesyofAndreasSchachner 196

5.4.ExtensivecolophononlibrarytabletKBo23.103fromHattusa ©Hethitologie-PortalMainz(MainzerPhotoarchiv);hethiter.net199

5.5.(a)TabletlabelKBo13.90fromHattusa.(b)TabletlabelKBo31.33 fromHattusa

©Hethitologie-PortalMainz(MainzerPhotoarchiv);hethiter.net200

6.1.ClaytabletinscribedwithUgariticBaalCyclefromthe ‘Houseofthe HighPriest’ inUgarit

PhotocourtesyofLesfrèresChuzeville,©RMN-GrandPalais/Art Resource,NY 217

6.2.Planofthe ‘HouseoftheHighPriest’ (MaisonduGrand-prêtre) inUgarit

IllustrationcourtesyofM.Yon,afterSaadé2011:280, fig.88a 220

6.3.Planofthe ‘HouseofUrtēnu ’ inUgarit

IllustrationcourtesyofM.Yon,afterSaadé2011:241, fig.79a 224

6.4.PlanofthecityofEmar-Bālis

IllustrationcourtesyofU.FinkbeinerandF.Sakal 228

6.5.Claymodelofasheep’sliverwithAkkadiancuneiforminscription from ‘TempleM₁’ inEmar PhotocourtesyofErichLessing/ArtResource,NY 229

6.6.PlanoftheLowerTownwith ‘TempleM₁’ (templedudevin)inEmar IllustrationcourtesyofU.FinkbeinerandF.Sakal 230

7.1.MapofthecentralquarterofTellel-Amarna,showingthelocationof the ‘HouseofLife’ andthe ‘RecordsOffice ’ (‘PlaceofDocuments ofPharaoh’ wherethecuneiformlettersandliterarytextswerefound) AfterStevensonSmith(1998:184),courtesyofYaleUniversityPress247

7.2.Mapdetailwiththe ‘PlaceofDocumentsofPharaoh’ andthe ‘HouseofLife’ atTellel-Amarna FromPendlebury1951:II,pl.19 248

7.3.(a)AlettersentfromthekingofMitannitothekingofEgypt,with areceptionnoteinEgyptianwritteninblackinkunderneath thecuneiformmessage.(b)AletterfromthekingofMitanni tothekingofEgypt,withareceptionnoteinEgyptianwritten inblackinkonthesideofthecuneiformtablet (fromWinckler1889:19)

(a)©TrusteesoftheBritishMuseum.(b)©StaatlicheMuseenzuBerlin249

7.4.HieraticostracafromanareaoftheRamesseumwhichhasbeen interpretedasa ‘school’ ora ‘HouseofLife’ CopyrightthePetrieMuseumofEgyptianArchaeology,UCL. FacsimilesafterSpiegelberg1898:pls.VIIandXI 257

7.5.(a)AfaïencelabelforacontainerforapapyrusrollbelongingtoKing AmenhotepIII; ‘BookoftheMoringaTree’.(b)Afaïencelabelfora containerforapapyrusrollbelongingtoKingAmenhotepIII; ‘Book ofthePomegranate’

(a)©TrusteesoftheBritishMuseum.(b)©YaleUniversityArtGallery260

7.6.MapofthevillageofDeirel-Medinawiththe find-spotofthefamily libraryofQenherkhepshef

AfterCastel1980:planno.1;courtesyoftheIFAO,Cairo 279

7.7.Photographofthe findspotofthelibraryofQenherkhepshef (markedbyarrow);takenwhilelookingnorth-west,withthewestern villagewallafewmetresbehindthecamera CourtesyofRichardParkinson 280

7.8.(a)AschematicdrawingofthefrontofPapyrusChesterBeattyI. (b)AschematicdrawingofthebackofpapyrusChesterBeattyI DrawingsbyFredrikHagen 287

7.9.(a)Anexampleofapapyrusfromaprivatelibraryofthe NewKingdom:column fiveofP.ChesterBeattyI,from thelibraryofQenherkhepshef(c.1300–1200 ) (b)DetailfrompapyrusChesterBeattyI(column16,line9),showing theerasedtitleandnameoftheoriginalcopyistandtheinsertion ofthewords ‘madebyNakhtsobek,scribeoftheNecropolis’ ©TheChesterBeattyLibrary 288

7.10.ThefamilyofthescribeQenherkhepshef AfterPestman1980:160andDavies1999:chart25 293

7.11.Adepictionofthe ‘PlaceofDocumentsofPharaoh’ inPiramesse, fromThebanTombno.23 AfterBorchardt1907:59 fig.1

302

8.1.Pigeon-holesfortabletsinRoom5ofNabu’stempleinDur-Sharrukin, c.705 AfterLoud&Altman1938:pl.19c,courtesyoftheOrientalInstitute oftheUniversityofChicago 324

8.2.TheviewfromthetabletroomintoNabu’sshrineintheEzidatemple, Kalhu PhotobySaadEskander,2017 335

8.3.SchooltabletBM77665obverseandreversebearingacolophon dedicatedtoNabu,northernBabylonia, c.550 ©TheTrusteesoftheBritishMuseum 341

8.4.A3DreconstructionoftheReš templeinSeleucidUruk,withAnu’ s zigguratintheforeground ©artefacts-berlin.de;Material:GermanArchaeologicalInstitute348

8.5.ThecuneiformtabletTCL6:10(AO6466),obverseandreverse writtenbyNidinti-AnuinUrukin222

©RMN,MuséeduLouvre 351

9.1.Sketch-maptoshowtheprincipalsitesatKuyunjik AfterReade2000:192 fig.2 372

9.2.Assurbanipal’sinscriptionL⁴ (K2694+3050),whichincludes thecleareststatementofhisscholarlyabilities ©TrusteesoftheBritishMuseum 374

9.3.Amuch-travelledtablet(K6073+Bu.91-5-9,132.)containing apowerfulspelladdressedtotheSungodtobanishghosts, inconspicuouslylarge,clear,even ‘textbook’ Neo-Babylonianscript ©TrusteesoftheBritishMuseum 380

9.4.TabletK8289,whichwaswrittenfortheNabuTempletabletcollection ©TrusteesoftheBritishMuseum

383

10.1.GeneralplanofthetownofTebtunis AfterRondot2004:plan2;courtesyofInstitutfrançaisd’archéologie orientale 394

10.2.(a)SchematicofBuilding32,partiallyreconstructed,withindication ofthetwocellarsinwhichthetemplelibrarydepositwasdiscovered. AdaptedfromGallazzi2018:142–3, figs7and12.(b)Thetempleof SoknebtuniswiththeinnerpartofthetempleandBuilding32 markedwithgreyshadingAfterRondot2004:plan2; courtesyofInstitutfrançaisd’archéologieorientale

10.3.Groundplan(a)andprofile(b)oftowerhouseK19,nexttothe templeofKhnumatElephantine,whereseveraljarsfullofpapyriwere found insitu

396

10.4.TheentrancetothetemplelibraryatthetempleofHorusatEdfu CourtesyoftheHorusBehedetyProjectoftheJuliusMaximilian UniversityWürzburg,2018 425

10.5.PlanofthetempleofHorusatEdfu;thearrowmarksthelocation ofthetemplelibrary AfterPorter/Moss1939:120

10.6.ReliefdepictingPtolemyVIIIpresentingbookchestswithleather rollstothefalcon-headedHorusofEdfu AdaptedfromChassinat1929:pl.82

427

429

10.7.(a)Nicheforstoringpapyriontheeastwallinsidethetemplelibrary atthetempleofHorusatEdfu.(b)Theoreticalstackingofpapyriwith theEdfulibraryniches (a)CourtesyofKimRyholt,2007.(b)DrawingbyKimRyholt430

10.8.PlanofthetempleofIsisatPhilae;thearrowmarksthelocationofthe templelibrarybehindthecolonnade CourtesyofAncientEgyptianArchitectureOnline(Aegaron): Philae,CentralBuildingsandSurroundings,no.0005 434

10.9.(a)InnerpartofthetempleofMonthatMedamudwiththepossible locationofthetemplelibrarymarkedbythearrow.(b)Innerpart ofthetempleofNekhbetatel-Kabwiththepossiblelocation ofthetemplelibrarymarkedbythearrow (a)AdaptedfromBissondelaRoque1927:pl.1 (b)AdaptedfromClarke1922:pl.6 437

10.10.(a)ThePtolemaicadditiontothetempleofMonthatTod (b)ThenorthernnicheatthetempleofMonthatTod (a)AdaptedfromBissondelaRoque1937:pl.1 (b)CourtesyofDietrichWildung 439

10.11.(a)PlanofthetempleofRenenutetatNarmuthis.(b)Cluster ofbuildingsdesignatedHouseI-IVbuiltagainsttheinside oftheeasterntemenoswall.Thetwojarswiththe1300ostraca werefoundinthenicheoffthesouth-easterncornerofHouseIII, markedx

AdaptedfromBresciani2003: fig.10;courtesyofEddaBresciani442

10.12.ThelargerofthetwoostracajarsatNarmuthis insitu butnowmuch damaged

CourtesyofLuigiPrada,2011 443

10.13.(a)SketchofthetemplecompoundatTellTukhel-Qaramus. (b)Insert:thebuildinginwhichthetreasureandpapyriwerefound (a)AdaptedfromNaville/Griffith1890:pl.9.(b)Adaptedfrom Edgar1907:207 454

Whilsteveryefforthasbeenmadetosecurepermissiontoreproducethe illustrations,wemayhavefailedinafewcasestotracethecopyrightholders.If contacted,thepublisherwillbepleasedtorectifyanyomissionsattheearliest opportunity.

1.1.Aselectionofcollectionsandassemblagesofliterary textsfromEgyptandWesternAsia56

2.1.Generaloverviewofthemajor findsoftextsandattestedtextual genresoftheUruk,EarlyDynastic(OldSumerian),and OldAkkadianperiods

2.2.Textscomingfromthe ‘TabletHouse’ (atXVh)

2.3.Textscomingfromthelocus ‘NorthofXVh’

2.4.TextswithanoriginfromHouseIXacandIXaa

2.5.TextswithanoriginfromIXf–g78

–IIi

2.11.The ‘TabletHouse’ (atXVh)inShuruppag

2.12.TabletsfoundinShuruppagNorthofXVh

2.13.TabletsfoundinShuruppaginHouseIXacandIXaa

2.14.TabletsfoundinShuruppaginHouseIXf–g

2.15.TabletsfoundinShuruppaginTrenchHJ–IIi

2.16.TabletsfoundatTellAbuSalabikh,AreaERooms11,20,21,and31106

4.1.ThesequenceoftheelementaryscribalcurriculumatNippur 177

4.2.CompositionsattestedatbothHouseFandNo.1BroadStreet 182

4.3.CompositionsonlyattestedatHouseF 183

4.4.CompositionsonlyattestedatNo.1BroadStreet 184

5.1.Dateofthetextsinrelationtotheir find-spots 197

5.2.Textswithprescriptiveanddescriptivefunction(basedonvanden Hout2002) 205

5.3.Typologyofthetabletcollections 206

6.1.Cuneiformtabletsandartefactsfromthe ‘HouseoftheHighPriest’ , Ugarit 221

6.2.Cuneiformtabletsfromthe ‘HouseofUrtēnu ’,Ugarit 226

6.3.Cuneiformtabletsfrom ‘Temple’ M₁,Emar.Syrian(S), Syro-Hittite(SH),anduncertain(?)scribaltraditions 232

7.1.Alistofmanuscriptsandcompositionsbelongingtoaprivatelibrary ofthe18thDynasty266

7.2.Alistofmanuscriptsandcompositionsbelongingtoaprivatelibrary fromPerunefer,datedtothe18thDynasty268

7.3.AlistofmanuscriptspossiblyfoundtogetherinatombatSaqqara (c.1200 )

7.4.AlistofmanuscriptsbelongingtothelibraryofInena,ascribe associatedwiththeroyaltreasury(c.1200 )

7.5.AlistofmanuscriptsbelongingtothelibraryofQenherkhepshef andhisfamilyfromDeirel-Medina(c.1240–1120 )

7.6.Alistofmanuscriptsbelongingtoaprivatelibraryofthe 21stDynasty(c.1000 ),probablyfoundatel-Hibeh

7.7.Alistofmanuscriptsfromalibrarybelongingto(?) Djedmontuiufankh,apriestofAmun-Reandoverseer oftheroyaltreasury

8.1.Scholarlytabletcollectionsfoundin first-millenniumAssur (afterPedersén1985–6;1998:132–43)

8.2.ScholarlytabletcollectionsfoundinNeo-AssyrianKalhu, Dur-Sharrukin,andNineveh(afterPedersén1998:143–78)

325

8.3.Scholarlytabletcollectionsfoundinwesternprovincialtowns oftheAssyrianEmpire(afterPedersén1998:178–81;Robsonetal. 2007–;Harrison2012) 326

8.4.ScholarlytabletcollectionsfoundinNeo-andLateBabylonian Babylon(afterPedersén1998:183–91;2005:188–283 passim) 328

8.5.ScholarlytabletcollectionsfoundinnorthernBabyloniancities oftheNeo-andLateBabylonianperiods

8.6.ScholarlytabletcollectionsfoundinsouthernBabyloniancities oftheNeo-andLateBabylonianperiods(afterPedersén1998: 206–12)

10.1.Chronologicalchart

10.2.Building32measurements

330

332

10.3.PublishedliterarypapyrifromtheGermanexcavationsatElephantine 1906–8.Nos.1–12havebeenassignedtotheSaïteperiodandno.13 totheearlyPtolemaicperiod,whileno.14cannotbepreciselydated404

10.4.The ‘BrooklynLibrary’ (listofthepublishedorcitedpapyri) 409

10.5.TomblibraryofSminissonofPetemestusandIthorôscalledSentaës412

10.6.Akhmimtomblibraries 416

10.7.EgyptianliterarypapyrifromtheAbusirel-Melekcartonnages422

10.8.MeasurementsofthelibraryatthetempleofHorusatEdfu

428

10.9.MeasurementsofthetwonichesatthetempleofMonthatTod438

10.10.Locationsandsizesoftemplelibraries(theasteriskmarks conjecturedidentifications) 440

LibrariesbeforeAlexandria

KimRyholtandGojkoBarjamovic

1.1.THELIBRARYINALEXANDRIA

ThecreationoftheLibraryofAlexandriaiswidelyregardedasoneofthegreat achievementsinthehistoryofhumankind agiantendeavourtoamassall knownliteratureandscholarlytextsinonecentrallocationsoastopreserve itandmakeitavailableforthepublic.Inturn,thiseventhasbeenviewedas ahistoricalturningpointthatseparatestheancientworldfromclassical antiquity.Standardworksonthelibrarycontinuetopresenttheideabehind theinstitutionasnoveland,atleastimplicitly,aproductofGreekthought.¹

Yet,althoughthescaleofthecollectioninAlexandriaseemstohavebeen unprecedented,thenotionofcreatingcentralrepositoriesofknowledge,while perhapsnewtoGreektradition,wasage-oldintheNearEastwherethe buildingwaserected.Heretheexistenceoflibrariescanbetracedbackanother threemillennia,andthecreationoftheLibraryinAlexandriawasnotasmuch thebeginningofanintellectualadventureastheimpressiveculminationofa longtradition.

Seeninthiscontext,itisnocoincidencethattheLibraryofAlexandriawas builtinEgyptandnotinGreeceitself.PtolemyIestablishedforhimselfa kingdominaregionthathadbothanancienttraditionoflibrariesandan outstandingreputationforwisdomintheMediterraneanworld.Forgenerations,GreeksphilosophershadtravelledtoEgyptintheirquestforknowledge,tothepointwhereitbecamearecurrentthemeorideaincontemporary

¹Cf.e.g.theoptimisticaccountbyEl-Abbadi1990andhis2016articlefor Encyclopædia Britannica,aswellasCasson2001:31f.MacLeod2004isslightlymorecarefulregardingthe noveltyandGreeknessoftheLibrary,butalsotendstotakeancientsourcesatfacevalue,cf.e.g. pp.4–5.EventhecriticalarticlebyJohnston2014referstothe ‘inventionofthelibrary’ (passim) andclaimsthatfor ‘the firsttimewecanseealibraryasaninstitution’,buildingonasomewhat circulardefinitionoftheterm ‘library’ itself(p.356).Anewandmoresoberapproachtothe historiographywasopenedupbyBagnall2002withameticulousdismantlingofthewritten traditiononwhathecalleda ‘LibraryofDreams’ .

KimRyholtandGojkoBarjamovic, LibrariesbeforeAlexandria In: LibrariesbeforeAlexandria: AncientNearEasternTraditions.Editedby:KimRyholtandGojkoBarjamovic,Oxford UniversityPress(2019).©OxfordUniversityPress.DOI:10.1093/oso/9780199655359.003.0001

thinkingthatmanyofthegreatestmindshadstudiedthereatonetimeor another.Togiveanexample,thewell-informedauthorPlutarchin DeIsideet Osiride 10claimedthatSolon,Thales,Plato,Eudoxus,andPythagorasall studiedwithpriestsinEgypt.Whilesuchclaimsareinherentlydifficultto proveinthecaseofindividualphilosophers,theyaresufficientlycommonto provideevidenceofanestablishedtradition.

PtolemyIwouldhimselfhavebeenwellawareoftheintellectualreputation enjoyedbyEgyptinhistime.Significantproofofthisisthatoneofhis firstacts asarulerwasadeliberateretrievalofthecorpusofEgyptiantempleliterature, whichhadbeenremovedbythePersiansduringtheirsecondoccupationof Egypt343–332 .Infact,thisaccomplishmentwassoimportantinPtolemy’ s self-representationthatitwasgivenpriorityevenoverthefoundationofthe cityofAlexandriaontheso-called SatrapStele erectedin311 (Ryholt §10.11).ThecircumstancethatPtolemyinthisinscriptionexplicitlymentionedthereturnoftheEgyptiantempletextsunderlinesastrikingcontrast totheLibraryofAlexandria,whichisneveroncereferredtointheextant, contemporarydocumentsofthePtolemaickings.

ItremainsuncertainwherethetextswhichPtolemyclaimsheretrieved weredepositedupontheirreturn,butsinceEgypthadlongattractedGreek philosophers,theideaofcreatingadesignatedspacewheretheymightundertaketheirstudiesintheirnativetongueseemsareasonableextensionofthis activity.Thecostlyundertakingwashardlyaltruisticinnature.Incontrastto theconstructednarrativeofauniversallibrarywiththeprimarypurposeof preservingtraditionandfacilitatingscholarshipinitsownright,thebuilding ofthelibrarywasmorelikelyanactiondesignedtopromotecarefullyplanned politicalambitions.Ptolemyhadforgedanewmajorkingdominthecontext ofcriticalpoliticaltensionandoutrightrivalrythatfollowedthedeathof AlexandertheGreat,anditwasnecessarytolegitimizesuchambitions throughvariousmeasures,bothtowardalocalEgyptianaudience,andtothe Hellenisticworldatlarge.Ptolemy’sseizureofAlexander’sbody,anditsburial inEgypt,wasoneofthemostdramaticandsymbolicallyladenofthese undertakings.Buttheformergeneralalsoauthoredanowlostbiographyof Alexander,inwhichhenodoubtpromotedhisownroleinrelationtothe king.Theestablishmentofalarge-scalelibraryatthenewroyalresidence inEgypt,andtheprospectofgenerousfunding,mayberegardedasfurther meanstopromotetheseefforts essentiallycreatinganobjectofaristocratic androyaldisplayandpropaganda(Johnstone2014:349).Itmadeitpossible toattractrenownedphilosopherstotheroyalresidence,andsotosetupa royalcourtthatwouldlendlegitimacytothenewdynasty.Whethertheideaof buildingagrandlibraryinAlexandriawasconceivedalreadyduringthe lifetimeofPtolemyI,orwhetheritonlyappearedbythetimeofhis successor ancienttraditionsareinconflictonthispoint remainsimmaterialinthisrespect.Thiswasaregionthathadastandingtraditionfor

librariesandanintellectualreputation.The firstrulerofPtolemaicEgypt chosetoengagewiththistraditionfromtheoutset.

AnalogousdevelopmentsintheothermajorsuccessorstatesofAlexander’ s empire,includingtherivalSeleucidEmpireinmodern-dayIraq,pointtoa common Zeitgeist inpoliticalthought,butfactualdetailsoutsideofEgyptare vague.AlthoughnoindividualcollectionachievedthefameofitsEgyptian contender,Seleucidpatronageproducedgreathistoricalwritersandscholars (Kurth1987),whoformedthevenueoftransmissionfortheEasternlibrary traditionintotheGreekworld(Frahm2005;Goldstein2010:201–3).Tracing developmentsintheEastfurtherback,Beaulieu(2006:28–32)hasarguedthat theexposureofAlexander’sgeneralstothegreattemplelibraryofMarduk inBabylonandthetraditionofAssurbanipalaspatronofaroyalcollection mayalsohavebeenimportantstimulibehindthecreationoftheLibraryin Alexandria.

DespitetheenthusiasticreceptionofEgyptianand ‘Oriental’ wisdomin classicalandHellenistictimes,thereisalimitedappreciationinmodern scholarshipofwhatcentralandmulti-facetedroleslibrariesplayedthroughout theNearEastalreadymanycenturiesbeforethefoundingofAlexandria.This istruebothinrespecttothelibrariesintheircontemporarysocialcontext, andasaprecursorforlatertraditions(duToit2011).Thismayinpartbedue toahistoricalbias perhapslargelyunconscious thatfavoursGreekand Westerntraditions.Thephenomenonwasmuchmorepronouncedinthepast thanitistoday,whenclassicalscholarsoftenmakegreateffortstotakethe traditionsandinfluenceofborderingareasintoaccount.Butamoredirect causeisthemannerinwhichNearEasternmaterialhasbeenstudiedand presentedbythescholarswhoworkonit.Muchoftheevidenceforearly librarieshasbeendiscussedbyAssyriologistsandEgyptologistsprimarilyin communicationsaimedattheirownscholarlycommunities,andthrough specializedpublicationsinajargonandwithanattentiontodetailthatdoes notfacilitateeasyaccessbycolleaguesfromother fields.

ItisthussymptomaticthatasynthesisoftheNearEasterntraditionforthe benefitofabroaderaudiencehasnotpreviouslybeenattempted.Theclosest efforttodateistheoverviewof LibrariesintheAncientWorld byLionel Cassonfrom2001,whichseekstoincludeNearEasternmaterial,butfailsto usemuchoftheless-accessiblesecondaryliterature.Asaresult,theearlypart ofhisvolumefocusesprimarilyonthewell-knownseventh-century LibraryofAssurbanipalatNineveh,anditomitstheevidencefromEgypt entirelywiththesinglecommentthat: ‘Thoughitproducedarichbodyof writings,bothtechnicalandliterary,ithasnothingtoaddtothehistoryof libraries.Theyexistedthere,tobesure,butweknowofthemonlyvaguelyand indirectly’ (Casson2001:15–16).

ThisbringsustoanotheraspectoftheLibraryofAlexandria onethat contrastssharplywiththeearlierevidencefromtheancientNearEast.Asfar

astheancientworldisconcerned,theLibraryofAlexandriaranksamongits mostwidelyknownachievements.Whatislesswellknownoutsideacommunityofspecialistsisthatourknowledgeofthatlibraryishighlyrestricted bythefactthatwelackanyformofcontemporarysourcesaboutit.Nota singlemanuscriptfromthecollectionsurvives,andnotasinglebrickorstone fromthebuildinghasbeenpositivelyidentified.Wehavenophysicalevidence foritslocation,size,orlayout,andallourknowledgeaboutitisbasedonlater secondaryandderivativesources.²Moreover,latertraditionoftenprovides conflictinginformation,evenaboutsuchfundamentalaspectsasthedateof creationandscopeoftheLibraryinAlexandria.Thisproblematicsituation,and acriticalassessmentofthedesperatemeasurestowhichscholarshaveresorted inordertocreateadetailedhistoryoftheinstitution,areskilfullyoutlinedby RogerBagnall(2002)in Alexandria:LibraryofDreams.Despitehiscaution, however,somescholarsstillinsistonanacceptanceofthemostinflated figures foundinlatertraditioninrelationtothesizeandcontentsofthecollection. IncontrasttotheLibraryofAlexandria,virtuallyallevidenceforlibrariesin theancientNearEastpresentedwithinthisvolumederivesfromprimary sources.Aboveall,itconsistsofactualmanuscriptsthatwereconsultedbyan ancientaudience.Inseveralcasesweevenhaveatourdisposaltheremainsof librariesfoundintheiroriginalcontext,i.e.thephysicallocationswherethey werecreatedandusedinantiquity.Andbecausesomanymanuscriptsare preserved,weareofteninapositiontoseeexactlywhattheancientuserssaw: wecanliterallyholdandstudythesamephysicalmanuscriptsandobserve howtextswerewritten,arranged,andorganized.Wecanlearnthestyleof writingandparsing,inspecterrorsandcorrections,andformanimpressionof thephysicalpropertiesofthecollections.Sometimeswecanevenascribea groupoftextstospecificindividualsonthebasisofcolophonsordistinctive traitsinthehandwriting.Inshort,wegaininsightintothedetailsofthephysical worldoflibraryandscribalculturethatarerarelyavailableintheGraecoRomanworldoutsideofEgypt.

1.2.ACOMPARATIVEAPPROACHTOLIBRARIES INEGYPTANDWESTERNASIA

ThisvolumedrawsuponevidencefromtheentireancientNearEast,examiningboththecuneiformculturesofWesternAsiaandthewrittentraditions

²Thesameholdstruefortheso-calledLibraryofPergamum.Itsidentificationwithinthe ruinsofthesanctuaryofAthenaontheacropolisofPergamuminAsiaMinor,proposedinthe 1880sandfrequentlycitedeversince,hasnowbeenshowntobebaseless(Coqueugniot2013). 4 KimRyholtandGojkoBarjamovic

ofancientEgypt.Theapproachiscomparativeandbuildsuponmaterial datingtothe firstthreeandahalfmillenniaofwrittenhumanhistory, c.3300 –300 .Thereasontostudythetwoareastogetherseemstous asevidentasitisuncommonincurrentscholarlypractice.Therehavebeen previousattemptstostudytheliterarytraditionoftheancientNearEastasa whole,oftendrivenbyadesiretoshedlightonthewritingsoftheHebrew Bible.TheearlydevelopmentofscriptandliteracyinEgyptandWestern Asiahasalsoreceivedmuchattention.Buttherehasnotyetbeenacomparativestudyofthecollectionandpreservationoftheliterarytraditionin thespecificsense,inspiteofthefactthattheEgyptianandcuneiform corporashareimportantstructuralsimilarities,werecontemporaneous, andremainedincontactthroughouthistory.Moderndisciplinaryboundariesseemattimestobemoredif ficulttocrossthanancientfrontiers.The intentioninthisvolumeisthereforetocomparetwocloselyrelatedtraditions, allowingusnotonlytoextractnewdataandideas,butalsotoinspirenewsets ofquestionsandproduceanalyticaltoolsthathaveawiderapplication.

TheideaforthisbookgoesbacktoaconferenceheldatStAndrews Universityin2008onAncientLibraries(Königetal.(eds)2013),which includedtwopapersontheNearEastthatsoughttocontextualizetheriseof librariesintheclassicalworld.Theconferenceshowedthatrelativelyfew colleaguesoutsideAssyriologyandEgyptologywereawareoftheexistence oftheverylongtraditionand,aboveall,theabundantphysicalevidencefor librariesinthepre-HellenisticNearEast.Itthusexposedaneedforan accessiblesynthesisoftheevidencefortheearliestlibraries,bothintheir ownright,andasaprecursortoGraeco-Romantraditions.

Inoverviewsofclassicaltradition,theLibraryofAlexandriafrequently appearsasanembryonicexampleofwhatbecamethemajorinstitutional collectionsofwrittentradition oftenimplicitly,andsometimesdirectly, assumedtohaverisen exnihilo asacreationofearlyHellenistictradition.It israrelyasked why theLibraryofAlexandriawasbuiltinEgypt andnot Greece(orelsewhereintheHellenisticworld) andhowthecountlessworks itcontainedcameintobeing,ifnotfromanalreadyexistingtradition.The writingofanaccessiblesynthesisaboutlibrarytraditionsintheancientNear Eastthusbecameakeycomponentinabroaderresearchprojectdevotedto theexplorationoftheintellectualhistoryofancientMesopotamiaandEgypt, conductedattheCenterforCanonandIdentityFormationintheEarliest LiterateSocietiesaspartoftheUniversityofCopenhagenProgrammeof Excellencebetween2008and2013.

Insteadofwritingatop-downdescriptivevolumeaboutthedevelopmentof librariesinthepre-Hellenisticworld,ourapproachwastoengageagroupof specialistsfromvarioussubfieldswithinancientNearEasternstudieseachto workononegiventopicandasettask.Thepresentbookthereforeconstitutes acollaborationbetweenscholarswhoareallexpertphilologistsandhistorians