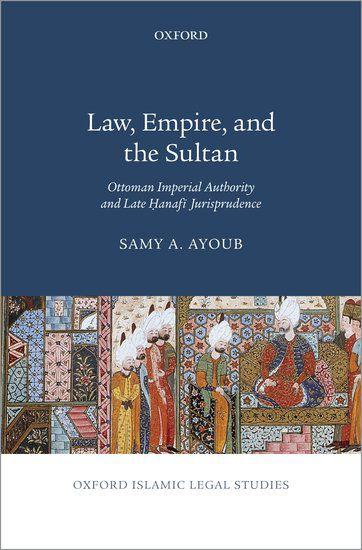

Series Editors’ Preface

The Oxford Islamic Legal Studies Series is pleased to feature Samy Ayoub’s important book, which brings together the histories of Ḥanafism and the Ottoman Empire in a generative study that furthers the historical analysis of both fields. Offering an account of “late” Ḥanafism, Ayoub brings both historiographical and institutional sensibilities to the study of Islamic law. Ayoub’s work will certainly challenge certain pieties that have long remained part of the Islamic legal studies field. From the interaction between Islamic law and the state, jurists and bureaucrats, legal argument and institutional enforcement, Ayoub’s work will no doubt inspire new questions and research trajectories in the near and distant future.

Anver M. Emon Clark B. Lombardi

Lynn Welchman

Permission

I would like to thank the following publishers for permission to reproduce certain materials included in this book.

An earlier version of Chapter 2 has appeared in the form of an article: Samy Ayoub, “The Sultan Says: State Authority in Late Ḥanafī Tradition,” Islamic Law and Society, (23) 3 (2016): 239–278 (copyright, Brill, 2016). This material has been reproduced with permission from Brill.

An earlier version of Chapter 4 has appeared in the form of an article: Samy Ayoub, “The Mecelle, Sharia, and the Ottoman State: Fashioning and Refashioning of Islamic Law in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries,” Journal of the Ottoman and Turkish Studies Association, (2) 1 (2015): 121–146 (copyright, Indiana University Press, 2015). This material has been reproduced with permission from Indiana University Press.

List of Figures and Tables

Figure I.2. Ibn Ṭulūn al-Dimashqī, al-Ghuraf al-ʿAliyya

Figure I.3. Al-Ḥā

Figure 1.1. Ibn Nujaym’s references to early and late Ḥanafī opinions

Figure 1.2. Al-Qūnawī, al-Fawāʾid al-Muhimma

Figure 1.3. References to Ibn Nujaym’s opinions in selected chapters of Ibn ʿĀbidīn’s Radd al-Muḥtār

Figure 1.4. References to Ibn al-Humām’s Fatḥ al-Qadīr in selected chapters of Ibn ʿĀbidīn’s Radd al-Muḥtār

Figure 2.1. Al-Shurunbulālī, “Itḥāf al-arīb,” al-Taḥqīqāt (King Saud MS)

Figure 2.2. Al-Shurunbulālī, “Aḥsan al-aqwāl,” al-Taḥqīqāt (King Saud MS) 76

Figure 2.3. Al-Shurunbulālī, “Aḥsan al-aqwāl,” al-Taḥqīqāt (King Saud MS)

Figure 2.4. Al-Shurunbulālī, “Tadhkirat al-bulaghāʾ,” al-Taḥqīqāt (King Saud MS)

Figure 2.5. Al-Shurunbulālī, “Tadhkirat al-bulaghāʾ,” al-Taḥqīqāt (King Saud MS)

Figure 2.6. Al-Shurunbulālī, “Tadhkirat al-bulaghāʾ,” al-Taḥqīqāt (King Saud MS)

Figure 2.7. Al-Shurunbulālī, “Tadhkirat al-bulaghāʾ,” al-Taḥqīqāt (King Saud MS)

76

77

78

80

81

Figure 2.8. References to Ibn Nujaym’s opinions in selected chapters of Shaykh-Zāda’s Majmaʿ al-Anhur 83

Figure 2.9. References to Ibn Nujaym in selected chapters of al-Ḥaṣkafī’s al-Durr al-Mukhtār 87

Figure 2.10. References to Abū al-Suʿūd’s Maʿrūḍāt in al-Ḥaṣkafī’s al-Durr al-Mukhtār 90

Figure 3.1. References to the late Ḥanafīs in selected chapters of Ibn ʿĀbidīn’s Radd al-Muḥtār 117

Figure 3.2. References to Abū al-Suʿūd’s Maʿrūḍāt in Ibn ʿĀbidīn’s Radd al-Muḥtār 120

Figure 3.3. References to sultanic orders and edicts (amr/manʿ/nahy sultanī) in Ibn ʿĀbidīn’s Radd al-Muḥtār 120

Figure 4.1. Mecelle-yi ahkâm-ı adliye (Istanbul: Matbaa-yı Osmaniye, 1882) 141

Table I.1. Examples of self-identified late Ḥanafīs 15

Table 1.1. Ibn Nujaym’s key sources and their origins 35

Table 3.1. Ibn ʿĀbidīn’s key sources, arranged by genre 98

Acknowledgments

This book was born out of my fascination with Zayn b. Ibrāhīm b. Muḥammad b. Nujaym’s (d. 970/1562–3) legal scholarship. He was among the first generation of Egyptian Ottoman Ḥanafīs whose opinions and works gained immense popularity and authoritativeness that shaped late Ḥanafī jurisprudence in the seventeenth to nineteenth centuries. My study of Ibn Nujaym introduced me to the development of late Ḥanafism.

My encounter with the Ḥanafī school started in 1994, when I started middle school in the Al-Azhar educational system of Egypt. On the first day of middle school, we were given a week to choose one of the available legal schools—Ḥanafī, Shāfiʿī, and Mālikī for our training throughout the middle and high school years until college. Symbolically, after joining a legal school, this decision cannot change. My interest in the Ḥanafī school started with my uncle, Muḥammad Ayoub––a Ḥanafī fiqh teacher at al-Azhar in Shubrakhit in the west Nile Delta of Egypt. In his attempt to convince me to join the Ḥanafī school, he assured me that “Abū Ḥanīfa is the master jurist.” I followed his advice and remained in the Ḥanafī class, which fluctuated for a week, until we had three equal classrooms distributed among the Ḥanafī, Mālikī, and Shāfiʿī schools. I was fortunate to have been trained with wonderful Ḥanafī teachers: Shaykh ʿAbduh ʿAnānī, Shaykh Basyūnī Abū al-ʿAdab, Shaykh Ibrahīm al-Saqqa, and Basyūnī al-Sanhūrī.

The first Ḥanafī text we studied and memorized was Ḥasan al-Shurunbulālī’s (d. 1659) Taysīr Nūr al-Īḍāḥ. This work was my first sustained introduction to learning how Muslim jurists discussed ritual purity, prayer, marriage, contracts, divorce, and inheritance. My journey into the Ḥanafī school started by acquiring the vocabulary of the jurists and mapping out the divergent positions among the disciples and the eponym of the school. Throughout these foundational years, the study of the Ḥanafī school meant, for me and my colleagues, something beyond mere intellectual curiosity or history. Ḥanafī norms were tangible and were reflected in persistent practices—such as the witr prayers (three units of prayers with one set of taslīm at the end) and the way we performed ritual ablution— within a dominant Shāfiʿī culture in the Nile Delta of Egypt. Moreover, Ḥanafīs have also permeated a key social event in the Delta—marriage ceremonies (katb al-kitāb), where the name of Abū Ḥanīfa and his school are still an integral part of the marriage proposal. This set of experiences, affinity, and familiarity have defined—for me—the relevance of the Ḥanafī school and Islamic law in general, and defied certain narratives about the madhhab, local practices, and relevance of the sharīʿa. This formative experience shaped my understanding of the sociology of Islamic law and gave me a unique perspective on its historical articulation. This book could not have been written without the help and support of Scott Lucas, Ahmad Atif Ahmad, Yaseen Noorani, and Maha Nassar. My experience at

Acknowledgments

the James E. Rogers College of Law was essential to my legal training. I am particularly grateful to Kay Kavanagh and David Marcus. They introduced me to American legal studies and shaped the ways I study and think about law. Guy Burak was kind enough to spend a great deal of time with me discussing his research on the Ottoman canon. These discussions with Guy sparked my interest to explore the different ways in which the Ottoman state was imagined in Ḥanafī juristic discourses.

There are many colleagues and friends who made the journey of writing this book possible. Guy Burak, Dale J. Correa, Anver Emon, Will Smiley, and Joshua White read the entire book manuscript and offered very helpful feedback and important suggestions that I incorporated into the book. Lena Salaymeh and Sohaira Z.M. Siddiqui read the introduction and suggested better organization and corrections. Mohammad Fadel commented on one of the chapters that I presented at the Middle Eastern Studies Association (MESA) meeting in 2013. I have discussed some of the arguments of this book in conversations during conferences, workshops, meetings, and phone and Skype calls with Asad Q. Ahmad, Kecia Ali, Omar Anchassi, Ovamir Anjum, Abdurrahman Atçıl, Nesrine Badawi, Jonathan AC Brown, Alexandre Caeiro, Janan Delgado, Moatasem al-Gheriani, Robert Gleave, Vanja Hamzić, Hadi Hosainy, Hedayat Heikal, Marion Katz, Mutaz al-Khatib, Hakan Karpuzcu, Brinkley Messick, Rudolph Peters, David Powers, Junaid Quadri, Kevin Reinhart, Adam Sabra, Safa Saracoglu, and Mohammad Sherine.

In Turkey, I thank Murteza Bedir, Tarık Çasşkurlu, Hatice Kübra Kahya, Said Salih Kaymakçı, Recep Şentürk, Hümeyra Özturan, Merve Özdemir, and Hacer Yetkin for their colleagueship and help during the research for this book. The archival research for this study was made possible by the financial assistance of the School of Middle Eastern and North African Studies (MENAS) and the Social & Behavioral Sciences Research Institute (SBSRI) at the University of Arizona. These funds allowed me to explore the manuscript collections of the Egyptian National Manuscript Library, the Süleymaniye Library in Istanbul, and the Rare Books and Special Collections at Princeton University. They also allowed me to spend four months at the Center for Islamic Studies (ISAM) in Istanbul, Turkey.

At the University of Texas at Austin, I am eternally grateful to Kamran Scot Aghaie, Robert (Bobby) Chesney, Donald Davis, Mary Rader, and Na’ama Pat-El for their support of my academic career, and facilitating the publication of this work. Bobby Chesney was a source of inspiration for my intellectual and professional development. Na’ama Pat-El vigorously supported my fellowship at the Netherlands Institute of Advanced Study (NIAS) in 2018–2019. I am grateful for all of my colleagues at the Department of Middle Eastern Studies and the University of Texas School of Law, particularly Hina Azam, Mahmud Al-Batal, Kristen Brustad, Karen Grumberg, Jonathan Kaplan, Faegheh Shirazi, Jeremi Suri, and Stephen Vladeck.

Anver Emon, a series editor of the Oxford Islamic Legal Studies series, made useful comments; while Jamie Berezin of Oxford University Press shepherded

the work through its production process. Hanna Siurua edited the entire manuscript and offered very important suggestions.

Dale J. Correa was key to the success of this journey. Her constant encouragement and belief in my scholarship assured me in the most difficult times of my writing. I am eternally grateful for her kindness, love, and companionship. I would like to acknowledge my three children, Rayhan, Surayya, and Idris, who brought meaning to my life and are a constant source of joy, comfort, and laughter. Finally, I would like to thank my family in Egypt, who sacrificed so much and worked so hard to make possible the opportunities that I have.

About the Author

Samy Ayoub is an Assistant Professor of Law and Middle Eastern Studies at the University of Texas at Austin. He specializes in Islamic law, modern Middle East law, and law and religion in Muslim societies. He focuses on issues concerning the interaction between religion and law, and the role of religion in contemporary legal and socio-political systems within a global comparative perspective. Dr. Ayoub was selected as a Fellow at the Netherlands Institute for Advanced Study (2018–2019). He also served as the President of the Islamic Law Section of the American Association of Law Schools (AALS) for 2018–2019, and he is a member of the Editorial Board of Arab Law Quarterly. Before joining the University of Texas at Austin, Dr. Ayoub was a postdoctoral faculty fellow (2014–2015) at the University of California, Santa Barbara, where he was nominated by the student body to the Margaret T. Getman Service to Students Award. He is the winner of the 2015 Malcolm H. Kerr Dissertation Award for the best dissertation in the humanities by the Middle East Studies Association (MESA). Dr. Ayoub earned his PhD in Islamic law from the School of Middle Eastern and North African Studies and the James E. Rogers College of Law at the University of Arizona. He earned a BA in Islamic jurisprudence from Al-Azhar University in Cairo, Egypt, in 2006, where he received systematic instruction in Ḥanafī jurisprudence. He also received an MSc. in Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies from the University of Edinburgh in Scotland, UK, in 2008.

Introduction

This book is the first study of late Ḥanafism in the early modern Ottoman Empire.1 It focuses on Ḥanafī juristic discourses and traces their various permutations and transformations over the course of the sixteenth to nineteenth centuries. I examine the legal scholarship of late Ḥanafī jurists, giving special attention to the Ḥanafī responses to Ottoman sultanic authority in the process of lawmaking. By considering the relationship between law and empire from the point of view of legal practitioners, I demonstrate how Ḥanafī jurists sustained and expanded Ottoman sultanic authority through careful investigation of late Ḥanafīs’ reformulations of their own school and their engagement with new notions of governance embraced by the Ottomans. Situated at the intersection of Ottoman and Islamic legal studies, this book opens up the Islamic legal universe to reconsider some of its entrenched premises.

It is accepted wisdom in the field that premodern Muslim jurists in their legal deliberations operated outside of government influence.2 But this study maintains that this view overlooks the ways in which Muslim jurists theorized and engaged with the political office of the Ottoman sultan or caliph and its relationship to issues of law, governance, and policymaking. The discussion about law and legality in the early modern Ottoman Empire brings to the fore key questions about political legitimacy, sovereignty, and the normativity of the Ottoman political order.

1 There are many studies that focus on the social and legal history of the Ottoman Empire, where the late Ḥanafī tradition played a central role in shaping policies in the imperial capital and the provinces. However, these studies generally do not address the emergence of distinct late Ḥanafī identities, sources, and doctrines. See, for example, Martha Mundy and Richard Saumarez Smith, Governing Property, Making the Modern State: Law, Administration and Production in Ottoman Syria (London: I.B. Tauris, 2007); Sabrina Joseph, Islamic Law on Peasant Usufruct in Ottoman Syria: 17th to Early 19th Century (Leiden: Brill, 2012); Guy Burak, The Second Formation of Islamic Law: The Hanafi School in the Early Modern Ottoman Empire (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015); Abdurrahman Atçıl, Scholars and Sultans in the Early Modern Ottoman Empire (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017); James E. Baldwin, Islamic Law and Empire in Ottoman Cairo (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2017); Baki Tezcan, The Second Ottoman Empire: Political and Social Transformation in the Early Modern World (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010).

2 See, for example, Wael B. Hallaq, “Juristic Authority vs. State Power: The Legal Crises of Modern Islam,” Journal of Law and Religion 19, no. 2 (2003–4): 250.

Law, Empire, and the Sultan. Samy A. Ayoub, Oxford University Press (2020). © Samy A. Ayoub DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780190092924.001.0001

Furthermore, this study incorporates empire as a mode of governance in the contestations about Islamic legalities during Ottoman rule.3 I analyze reformulations of Islamic law in the Ottoman imperial context and their lasting legacies in local and regional domains. Law occupies a central role in imperial governance. Ottoman sultans paid close attention to law because of its fundamental role in the preservation of social order. Exploring the relationship between law and empire invites us to consider the multiplicity of law and legal orderings. This approach also expands the legal sphere for different analytical potentialities and relieves the Islamic legal space of the burden of the ideological packages and presumptions about law and society that accompany the context of nation-states. Empires differ from nation-states as political entities. Jane Burbank and Fredrick Cooper explain that “the concept of empire presumes that different peoples within the polity will be governed differently.”4 Unlike state law, imperial law is negotiated, not imposed.5 Seeing law and empire as a paradigm allows us not only to examine law from the local point of view but also to demonstrate how legal traditions navigate and respond to the imperial will.

This framework of analysis addresses the challenges that lie at the intersection of law, governance, and imperial power. I believe that studying Islamic law within its imperial context permits serious interrogation of the role of Ottoman sultanic authority within the Islamic lawmaking process. I use the word “empire” to denote “rule over a diversity of people.”6 This approach casts law as a moral-political notion, as a practice of government, and as a social process. In the Ottoman context, Islamic law was necessary to provide a space of legitimacy, and it was essential for the longevity of the political order. Law forms part of the endeavor to integrate peoples into overarching political structures.7

Scholarship in the field draws a picture of diverse and plural legal regimes, which were integral parts of imperial governance. Ottoman studies scholars locate Ottoman rulership and lawmaking in the Islamic legal tradition. They are careful to differentiate between various practices of law, pointing to the coexistence of sharīʿa and sultanic qānūn. Ottomanists disagree, however, on how these two different sources of legality were deployed by the imperial power. Ottoman sultanic authority did not consume the entire legal space of the empire. Instead, it left room for Islamic law and social practice, which were meant to operate within the Ottoman imperial framework.

It is the contention of this book that analysis of Islamic law and society on the basis of a supposed epistemological conflict between law and imperial power is

3 By “Ottomans” I refer not only to the sultan but also to the ruling elite and the leadership of the empire. See Norman Itzkowitz, Ottoman Empire and Imperial Tradition (New York: Knopf, 1972).

4 Jane Burbank and Fredrick Cooper, Empires in World History: Power and Politics of Difference (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2010), 8.

5 Jill Harries, Law and Empire in Late Antiquity (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999), 36.

6 Jeroen Duindam, Jill Harries, Caroline Humfress, and Nimrod Hurvitz, “Introduction,” in Law and Empire: Ideas, Practices, Actors, ed. Jeroen Duindam, Jill Harries, Caroline Humfress, and Nimrod Hurvitz, 1–22 (Leiden: Brill, 2013).

7 Ibid.

simplistic and inaccurate in the Ottoman context. Instead, Ottoman jurists (and late Ḥanafī jurisprudence in particular) viewed Ottoman imperial enactments as authoritative and legitimate expressions of power. Late Ḥanafīs affirmed that Ottoman subjects were morally obligated to obey the sultan. However, they stressed that this authority was not absolute and that its validity was contingent on its meeting objectives of the sharīʿa, such as fairness and justice. In this regard, the authority of the laws of the sultan depended on “the inherent power of the office, approval of the imperial subjects, and self-assertion of the sulṭān over the governed.”8 The incorporation of imperial legislation into authoritative legal works by Ḥanafī jurists was a sign of the indispensable authority of the Ottoman sultans in the lawmaking process.

LAW AND THE SULTAN

The kings are the rulers of the people; the scholars are the rulers of the kings; and the law is the ruler of everyone.

Arabic proverb9

This book studies authoritative Ḥanafī legal works from the Ottoman world of the sixteenth to nineteenth centuries ce, casting new light on the understudied late Ḥanafī jurists (al-mutaʾakhkhirūn). Specifically, I interrogate the Ḥanafī legal tradition’s portrayal of Ottoman political authorities and their local actors and agents. To this end, I engage with works of Ḥanafī positive law (furūʿ)10 and case studies from the legal literature that reveal the Ḥanafīs’ negotiation of their relationship with Ottoman sultanic authority. My analysis shows that late Ḥanafī jurists assigned probative value and authority to the orders and edicts of the Ottoman sultan. This authority is reflected in the sultan’s ability to settle juristic disputes, to order specific opinions to be adopted in legal opinions (fatāwā), and to establish his orders as authoritative and final reference points. The incorporation of sultanic orders into authoritative Ḥanafī legal commentaries, treatises, and fatwā collections was made possible by a shift in Ḥanafī legal commitments that embraced sultanic authority as an indispensable element of the lawmaking process. I use the term “sultanic authority” to refer to political power within the Ottoman Empire. The sultan’s legal authority is a reflection of his power and his

8 Natalia Krolikowska, “The Law Factor in Ottoman-Crimean Tatar Relations in the Early Modern Period,” in Law and Empire: Ideas, Practices, Actors, ed. Jeroen Duindam, Jill Harries, Caroline Humfress, and Nimrod Hurvitz, 178–95 (Leiden: Brill, 2013).

9 Recep Şentürk, “Between Traditional and New Forms of Authority in Modern Islam,” in Tradition and Modernity: Christian and Muslim Perspectives, ed. David Marshall, 45–56 (Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, 2013), 45. This statement is attributed, without the last part (“the law is the ruler of everyone”), to Abū al-Aswad al-Duʾalī (d. 69/689). See Ibn Qutayba al-Dīnawarī, ʿUyūn al-Akhbār (Beirut: al-Maktab al-Islāmī, 2008), 1:185; Abū Ḥāmid al-Ghazālī, Iḥyāʾ ʿŪlūm al-Dīn (Cairo: Muʾassasat al-Ḥalabī, 1967), 1:47.

10 I use the phrase “positive legal works” to refer to the juristic production of Muslim jurists.

ability to enforce order. Late Ḥanafī jurists use the terms al-dawla al-ʿaliyya, alsalṭana al-ʿaliyya, al-dawla al-turkiyya, and al-dawla al-ʿuthmāniyya to acknowledge the authority of the sultan in their legal scheme.11

In addition, I draw on late Ḥanafī juristic literature to examine the ways in which these jurists articulated their own authority and the juristic discourse they espoused to construct late Ḥanafism in the early modern period. I pose the following questions: How can we explain late Ḥanafī jurists’ departure from the established norms of their school and their adoption of a new set of doctrines? What are the tools they used to justify such changes? In what ways did Ḥanafī jurists incorporate Ottoman edicts and orders? And how should we evaluate the codification of Ḥanafī legal doctrines in the late nineteenth century?

I contend that Ottoman jurists secured the authority of the late Ḥanafīs through (1) engagement with legal texts written by previous generations of Ḥanafīs, (2) disclosure of the reasoning that underpins late Ḥanafī legal opinions, and (3) invocation of the principles, authorities, and arguments that construct late Ḥanafism. I argue that the late Ḥanafī legal tradition developed its own distinct identity, opinions, and consensus in relation to early Ḥanafī opinions. Late Ḥanafī jurists formulated a set of juristic tools and devices to change, alter, or perpetuate early Ḥanafī opinions, even those that originated with Abū Ḥanīfa (d. 150/767), the eponym of the school. For instance, late Ḥanafīs employed the legal devices of necessity (ḍarūra), customary practice (ʿurf), change of time (ikhtilāf ʿaṣr wa-zamān), widespread communal necessity (ʿumūm albalwā), and others to justify fundamental changes in key Ḥanafī doctrines that transformed the classical opinions of the school. In fact, late Ḥanafīs invoked the authority of the eponym of the school in their legal formulations, insisting that “were [he] here, [he] would say the same [on this issue].”12 Beyond such legal devices, the late Ḥanafīs were also concerned with the contours of the role of the sultan in the process of lawmaking. I show that the late Ḥanafīs as a group are distinguished from their chronological predecessors within the school by their relationship with Ottoman sultanic authority and by their characteristic jurisprudential production. My analysis of their works provides evidence of the probative value of sultanic orders and edicts in authoritative Islamic legal commentaries (shurūḥ) and fatwā literature.

It is important to note that the late Ḥanafī tradition was essentially formulated and existed in conversation with early Ḥanafī methodological commitments and

11 Muḥammad Amīn b. ʿĀbidīn, Radd al-Muḥtār ʿalā al-Durr al-Mukhtār (Beirut: Dār al-Fikr, 1992), 4:180; Zayn al-Dīn b. Nujaym, al-Baḥr al-Rāʾiq Sharḥ Kanz al-Daqāʾiq (Cairo: Dār al-Kitāb al-Islāmī, n.d.), 5:76; ʿAbd al-Raḥmān b. Muḥammad Shaykh-Zāda, Majmaʿ al-Anhur fī Sharḥ Multaqā al-Abḥur (Beirut: Dār Iḥyāʾ al-Turāth al-ʿArabī, n.d.), 2:425.

12 Ibn ʿĀbidīn, Majmūʿat Rasāʾil Ibn ʿĀbidīn (Istanbul: Dār-i Saʿādat, 1907), 1:45; Ibn Nujaym, Rasāʾil Ibn Nujaym, ed. Khalīl al-Mays (Beirut: Dār al-Kutub al-ʿIlmiyya, 1980), 32. The statement in Ibn Nujaym’s treatise reads, “If the early Ḥanafīs had witnessed what the late Ḥanafīs are experiencing, they would have unanimously agreed with their opinions”; Hallaq, “A Prelude to Ottoman Reform,” in Histories of the Modern Middle East: New Directions, ed. Israel Gershoni, Hakan Erdem, and Ursula Woköck, 37–62 (Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner, 2002), 56.

doctrinal attitudes, on which it based its authority and formulations. For the late Ḥanafīs, the past was never irrelevant; it constituted a point of reference and a source of continuity for later Ḥanafī scholarship. In addition, late Ḥanafī jurists of the early modern period were particularly careful to pinpoint and distinguish local customs in Cairo, Damascus, and Istanbul (and Anatolia more generally), despite the geographical proximity of these centers of Ḥanafī training to one another. Such local practices and traditions were significant factors in their juristic discourse.

Furthermore, I demonstrate that confining the practical aspects of Islamic law to the Ottoman judiciary (court records and registers) rests on a mischaracterization of how late Ḥanafīs viewed the process of legal practice. In contrast to common law, which is found in precedents established by courts of law, Islamic law exists in a body of writings authored by jurists and muftīs.13 It would thus be misguided to attempt to understand juridical practice and reasoning in the Ottoman Empire without taking into account the authoritative positions of the madhhab at the time. The assumption that books of jurisprudence address theory while fatāwā and court records reflect actual practice and social reality is not indicative of the substance of the legal discourse of late Ḥanafī jurists.14 The latter insisted that the legal and judicial norms contained in their authoritative legal works should be prioritized above fatwā collections and adopted by judges in their legal rulings.15

The development of Ḥanafī jurisprudence during the Ottoman period presents a compelling case study of the incorporation of imperial orders and edicts into the authoritative opinions of a legal school. This development was reflected in the consistent adoption of Maʿrūḍāt Abū al-Suʿūd. The Maʿrūḍāt is a collection of fatāwā issued by the Ottoman Shaykh al-Islām Abū al-Suʿūd al-ʿImādī (Turk. Ebussuud Efendi, d. 1574) and sanctioned by Sultan Süleyman I (r. 1520–66).16 A key feature of the Maʿrūḍāt is its insistence on the obligation (ilzām) of the judiciary and jurists to act upon sultanic edicts. Ḥanafīs from the seventeenth to nineteenth centuries refer to the Maʿrūḍāt and emphasize the obligatory

13 Hallaq, An Introduction to Islamic Law (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009), 10.

14 Lena Salaymeh makes a similar observation in her study of Islamic law in the late antique period. She asserted that Islamic law is amalgamation of theory and practice. She traces the popular dichotomy between “law on the books” and “law in action” to the socio-legal studies which presented the study of legal practice in social contexts as a “corrective to the study of jurisprudential texts.” To Salaymeh, law is both what on the books and what is in action because “legal texts cannot be interpreted in isolation from their interpretive communities.” See Lena Salaymeh, The Beginnings of Islamic Law: Late Antique Islamicate legal Traditions (Cambridge: Cambridge University press, 2016), 202.

15 Ibn Nujaym, al-Baḥr al-Rāʾiq, 1:61; Ibn ʿĀbidīn, Minḥat al-Khāliq ʿalā al-Baḥr al-Rāʾiq, published together with al-Baḥr al-Rāʾiq by Ibn Nujaym (Cairo: Dār al-Kitāb al-Islāmī, n.d.), 1:89. They emphasize: “It is established that what is in the mutūn should be prioritized over what is in the shurūḥ, and what is in the shurūḥ should precede what is in the fatāwā.” See also Shaykh-Zāda, Majmaʿ al-Anhur fī Sharḥ Multaqā al-Abḥur (Beirut: Dār al-Kutub al-ʿIlmiyya, 1998), 1:341: “Al-iftāʾ bimā fī al-mutūn awlā.”

16 Abū al-Suʿūd Efendī, Maʿrūḍāt (MS, University of Michigan, Isl. Ms. 69 [5 fols., copied ca. 1149/ 1736]), fols. 268b–272a. The complete text of Maʿrūḍāt has been transcribed in modern Turkish; see Ahmet Akgündüz, Osmanlı Kanunnameleri ve Hukuki Tahlilleri (Istanbul: Fey Vakfı, 1992), 4:35–59.

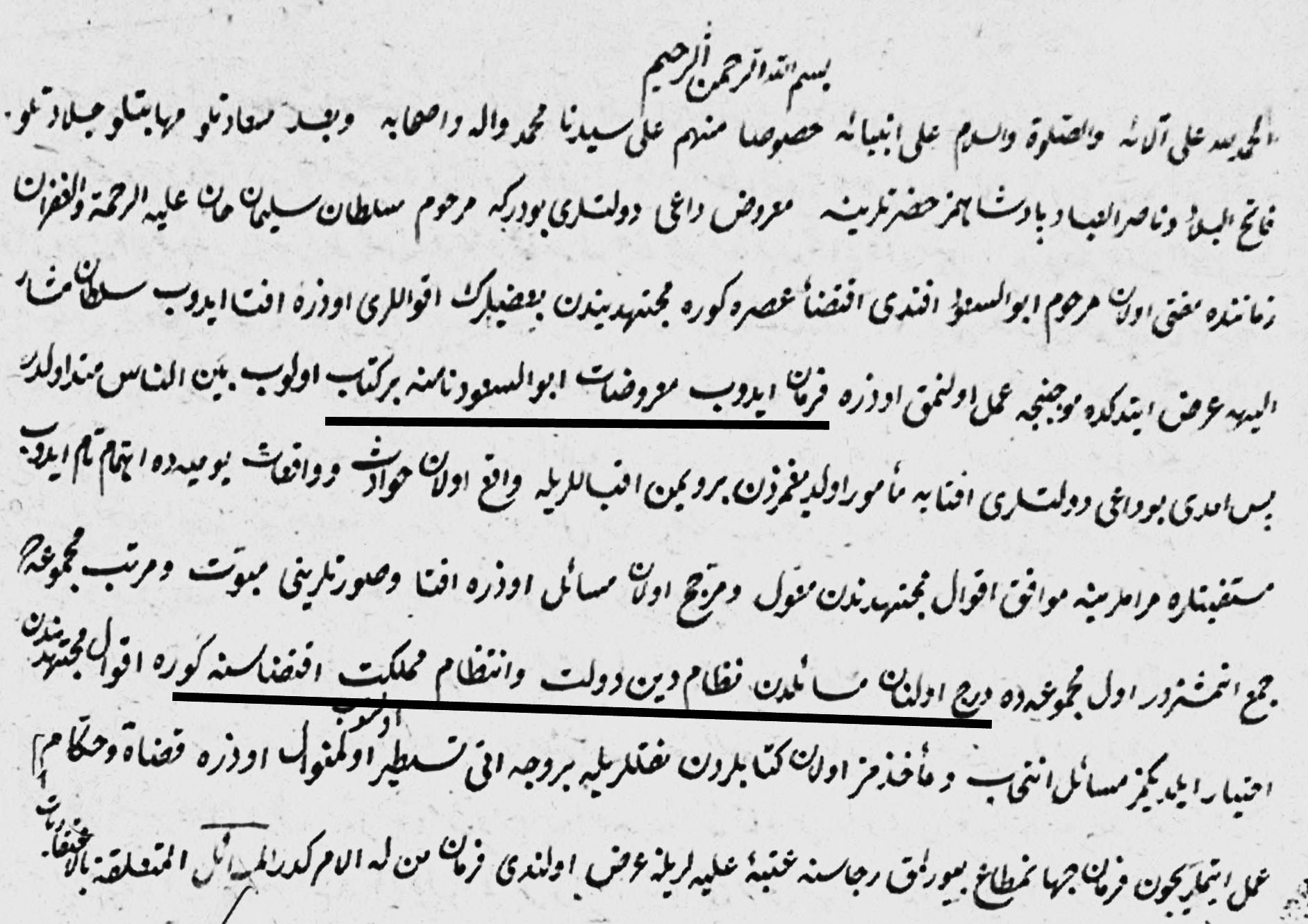

Figure I.1 Yenişehirli ʿAbd Allāh Efendī, Maʿrūḍāt, fol. 20a.

nature of such edicts in their legal commentaries and fatwā collections. Further, Yenişehirli ʿAbd Allāh Efendī (d. 1742–3), another Ottoman Shaykh al-Islām, embraced this view of sultanic authority in his legal writings. Under Sultan Ahmet III (r. 1673–1736), ʿAbd Allāh Efendī wrote another Maʿrūḍāt on the basis of his widely circulated and referenced Bahjat al-Fatāwā. 17 Building on the popular acceptance and effectiveness of Abū al-Suʿūd’s Maʿrūḍāt, he argued that a sultanic edict adopting his own Maʿrūḍāt would address newly emerging issues and preserve social and political order in the empire (see Figure I.1).18

The argument that Islamic law is the private and exclusive domain of the jurists and the characterization of any role for the political authorities in the lawmaking process as an encroachment on the legal domain need to be reconsidered. Ḥanafī legal literature from the Ottoman period draws a complex picture of the relationship between political and legal authorities. This literature recognizes a growing role for the Ottoman sultan in the making of Sunni jurisprudence. And it reveals spaces in which Ḥanafī legal doctrine was able to expand to incorporate the decisions and policies of the sultan. However, late Ḥanafī jurists did not take the contours of Ottoman imperial authority as given. They rejected, accepted, and expanded the policies and decisions made

17 Yenişehirli ʿAbd Allāh Efendī, Bahjat al-Fatāwā (Istanbul: Dār al-Ṭibāʾa al-ʿĀmira, 1849).

18 Yenişehirli ʿAbd Allāh Efendī, Maʿrūḍāt (MS, Süleymaniye, Bağdatlı Vehbi, 2054 [25 fols., copied ca. 1683]), fols. 20a–21b.

by the Sublime Porte. Ottoman sultans and their provincial deputies, such as governors, judges, and treasury officials, negotiated with Ḥanafī jurists on many issues involving political, social, and economic order in the Ottoman provinces. Their influence was mutual.

In early Ḥanafī legal discourse, the emphasis appears to be on political authorities’ upholding of the law, not their legislation of it. The enforcement of laws in Ḥanafī jurisprudence is closely connected to the political jurisdiction (dār). The existence of political jurisdiction, in turn, is dependent on the legal dominance of the political leader over the Muslim population. Some Ḥanafī jurists conditioned the categorization of a territory as Muslim versus non-Muslim jurisdiction (dār al-islām/dār al-kufr) on the ability of the political ruler to enforce the law. In this regard, the Ḥanafīs thus relegated the authority to apply the law exclusively to the political ruler.19 However, early Ḥanafī doctrine’s emphasis on the ruler’s upholding the law was, in late Ḥanafī thought, combined with the probative value of sultanic orders and edicts. Late Ḥanafī jurists opened up legal doctrine to allow a role for the sultan in the lawmaking process. This book uncovers the type of value that they assigned to the sultan’s orders in the hierarchy of authority within the Ḥanafī school.

PRINCIPAL QUESTIONS

Why Positive Legal Works?

A plethora of studies on the Ottoman ʿulamāʾ, court records, and registers have attempted to reconstruct the social and economic history of various regions of the Ottoman Empire.20 These studies have enriched our understanding of interconnected issues such as gender, the nature of the empire and local forces, nonMuslim communities under Ottoman rule, and fiscal matters such as land tax and rents. However, in these studies, Ḥanafī legal discourse is generally relevant only insofar as it serves a larger narrative concerning the political and social history of the Ottoman Empire. Consequently, these studies provide little systematic analysis of the Ḥanafī jurisprudential tradition as a sustained discourse indispensable to understanding legal developments within the Ottoman world.

19 Samy Ayoub, “Territorial Jurisprudence, Ikhtilaf al-Darayn: Political Boundaries and Legal Jurisdiction,” Contemporary Islamic Studies 2 (2012): 4–5, https://doi.org/10.5339/cis.2012.2.

20 Haim Gerber, “Shari‘a, Kanun, and Custom in the Ottoman Law: The Court Records of Seventeenth-Century Bursa,” International Journal of Turkish Studies 2 (1981): 138–47; Uriel Heyd, Studies in Old Ottoman Criminal Law (Oxford: Clarendon, 1973); Galal EI-Nahal, Judicial Administration of Ottoman Egypt in the Seventeenth Century (Minneapolis: Bibliotheca Islamica, 1979); Jon E. Mandeville, “Usurious Piety: The Cash Waqf Controversy in the Ottoman Empire,” International Journal of Middle East Studies 10 (1979): 289–308; Halil Inalcik, “Suleiman the Lawgiver and Ottoman Law,” Archivium Ottomanicum 1 (1969): 105–38; Judith E. Tucker, In the House of Law: Gender and Islamic Law in Ottoman Syria and Palestine (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998); Baldwin, Islamic Law and Empire.

This study focuses on positive legal works because they are the loci of central aspects of Ḥanafī legal discourse and its judicial practices. In Islamic law, legal manuals (mutūn) and commentaries (shurūḥ) influence all other forms of legal discourse, such as fatāwā, legal treatises, and judicial reasoning.21 In addition, the goal of this book is to examine the legal discourse of late Ḥanafī jurists in the early modern period as part of a sustained trajectory within the Ḥanafī school. It is important to stress that the law of Islam is found within a juristic body of writings recorded in the authoritative legal works (mutūn, shurūḥ, and fatāwā) written by Muslim jurists in various legal schools.22 Thus, in the premodern Muslim world, the decisions of judges were not treated in the manner they are in modern courts.23 Instead, the legal manuals, commentaries, and fatāwā not court decisions—were gathered and published as authoritative sources for determining the law.24 It is also crucial to recognize that “law in action is most clearly seen in the legal process and the juristic act.”25 In other words, legal norms were created, developed, and sustained within the context of the legal schools (madhāhib), with a community of jurists vetting all such norms. The Ḥanafīs insisted that judicial reasoning should be practiced within the confines of judges’ madhāhib; otherwise, they argued, judicial decisions would be based purely on personal discretion.26

Who Are the Mutaʾakhkhirūn?

There are no specific criteria to define early versus late Ḥanafīs; the terms are relative. We are told that the early Ḥanafī jurists are those who saw or met Abū Ḥanīfa (d. 150/767), Abū Yūsuf (d. 182/798), Muḥammad b. al-Ḥasan al-Shaybānī (d. 189/805), Zufar b. al-Hudhayl (d. 158/775), or Ḥasan b. Ziyād al-Luʾluʾī (d. 204/ 819).27 By contrast, the late Ḥanafīs (al-mutaʾakhkhirūn) are simply those who did not study with these authoritative figures. We are also told that the third century ah (tenth century ce) constitutes the fault line between the early and the late Ḥanafīs. This idea is further confirmed by the claim that the late Ḥanafīs are

21 Late Ḥanafīs consistently portray mutūn and shurūḥ as the prime sources for their juristic discourse and grant them more authoritative status than they do fatāwā and juridical decisions. See Ibn ʿĀbidīn, Radd al-Muḥtār, 1:72; Ibn Nujaym, al-Baḥr al-Rāʾiq, 1:247. They both state that al-ʿamal bima wāfaq al-mutūn awlā.

22 Hallaq suggests that Islamic law is found in “a juristic body of writings that originated mostly in the answers given by muftīs.” See Hallaq, Introduction, 10. However, late Ḥanafīs rank fatāwā below mutūn and shurūḥ in terms of authoritativeness. See Ibn ʿĀbidīn, Radd al-Muḥtār, 1:121, 153, 216.

23 Hallaq, Introduction, 10.

24 Ibid. A clear indication of this understanding can be observed in the publication of key Ḥanafī fatwā works as legal codes in colonial India. See Nawab Abdur Rahman, Institutes of Mussalman Law, a Treatise on Personal Law according to the Hanafite School, with References to Original Arabic Sources and Decided Cases from 1795 to 1906 (Calcutta: Thacker, Spink, 1907), 1–5.

25 Alan Watson, The Nature of Law (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1979), 8.

26 Muḥammad b. ʿAbd Allāh al-Timurtāshī, Masʿafat al-Ḥukkām ʿalā al-Aḥkām, ed. Ṣāliḥ al-Zayid (Riyadh: Maktabat al-Maʿārif, 1996), 2:627–29.

27 ʿAbd al-Ḥayy al-Laknawī, ʿUmdat al-Riʿāya ʿalā Sharḥ al-Wiqāya (Beirut: Dār al-Kutub al-ʿIlmiyya, 2009), 15–16; al-Laknawī, al-Fawāʾid al-Bahiyya, 241.

those who came after Shams al-Aʾimma al-Ḥalwānī (also known as al-Ḥulwānī or al-Ḥalwāʾī; d. 456/1063).28

ʿAbd al-Ḥayy al-Laknawī al-Hindī (d. 1886), a key later Ḥanafī authority, is a proponent of the latter view. He defines al-Ḥalwānī as the “landmark” between al-mutaqaddimūn (the early scholars) and al-mutaʾakhkhirūn (the late scholars).29 In Western scholarship, Baber Johansen suggests that late Ḥanafism starts in the eleventh century: “From the beginning in the eleventh century and continuing until the period of the Tanzimat (1839–76), the Ḥanafī jurists were aware of differences in conceptions and doctrines that separated the Hanafite doctrine of the ‘modern jurists’ (al-mutaʾakhkhirūn) from that of the ‘classical jurists’ (almutaqaddimūn).”30 Johansen points out that Ḥanafī jurists writing after the eleventh century repeatedly inform their readers that “they follow a legal doctrine that was developed by the ‘modern jurists.’ ”31

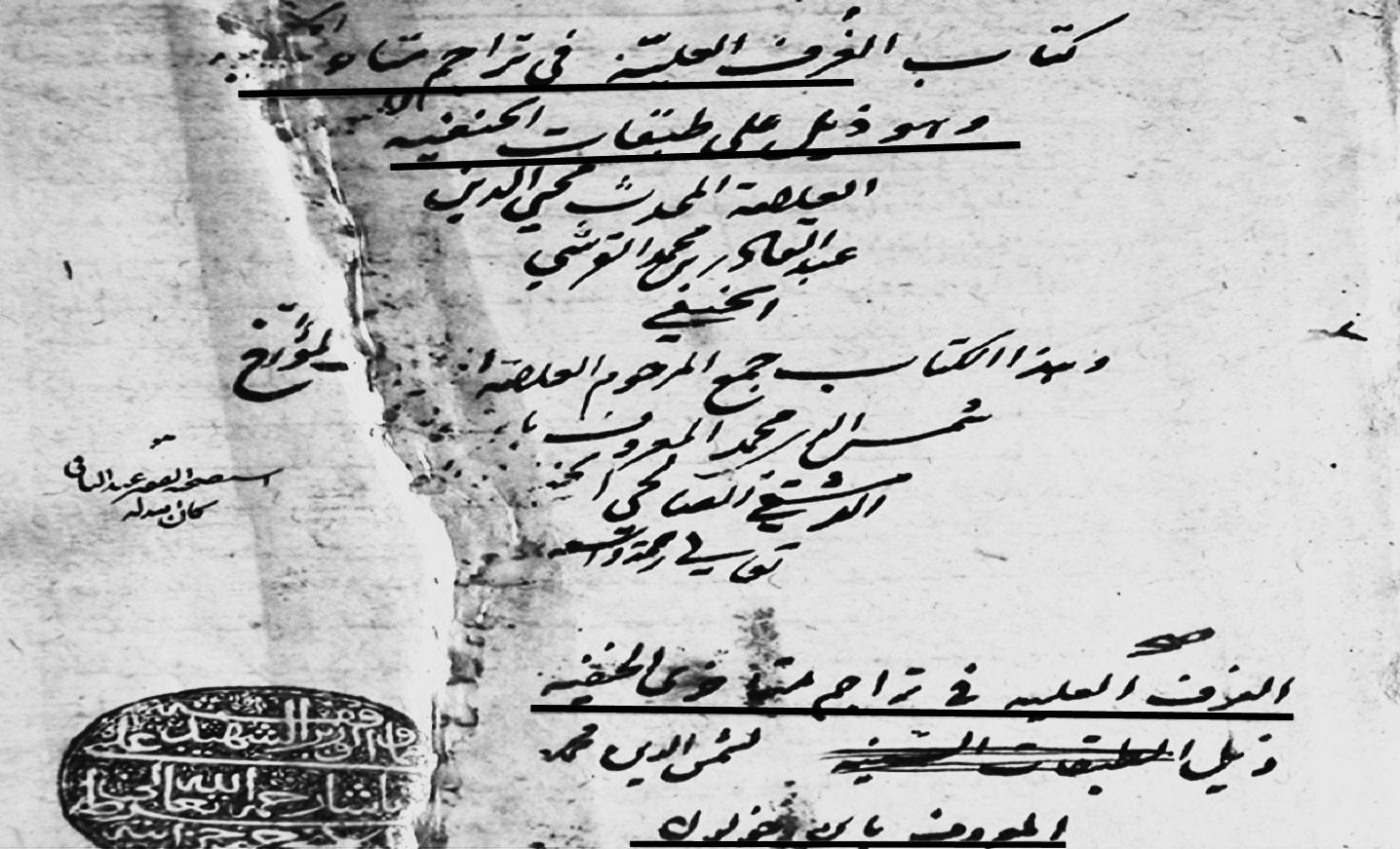

In this book, I propose to approach late Ḥanafī jurists in terms of their selfidentification and the legal patterns, opinions, and norms in their legal scholarship. For instance, the appellation “late Ḥanafīs” appears in the title of a biographical dictionary (ṭabaqāt) by Shams al-Dīn Muḥammad b. ʿAlī b. Aḥmad Ibn Ṭulūn al-Sāliḥī al-Dimashqī (d. 1546), al-Ghuraf al-ʿAliyya fi Tarājim Mutaʾakhkhirī al-Ḥanafīyya (see Figure I.2).32 The work was written in the first half of the sixteenth century and remains extant in manuscript form.33 Ibn Ṭulūn starts his work by providing biographical information on the founders of the school—Abū Ḥanīfa, Abū Yūsuf, and al-Shaybānī and then jumps ahead in time to the biographies of later Ḥanafīs, beginning with Ibrāhīm b. Aḥmad b. Khiḍr al-Ṣāliḥī alḤanafī (d. 1413). Overall, the work is primarily concerned with Ḥanafī jurists from the thirteenth to sixteenth centuries, the time frame that Ibn Ṭulūn adopts for his identification of late Ḥanafīs.34

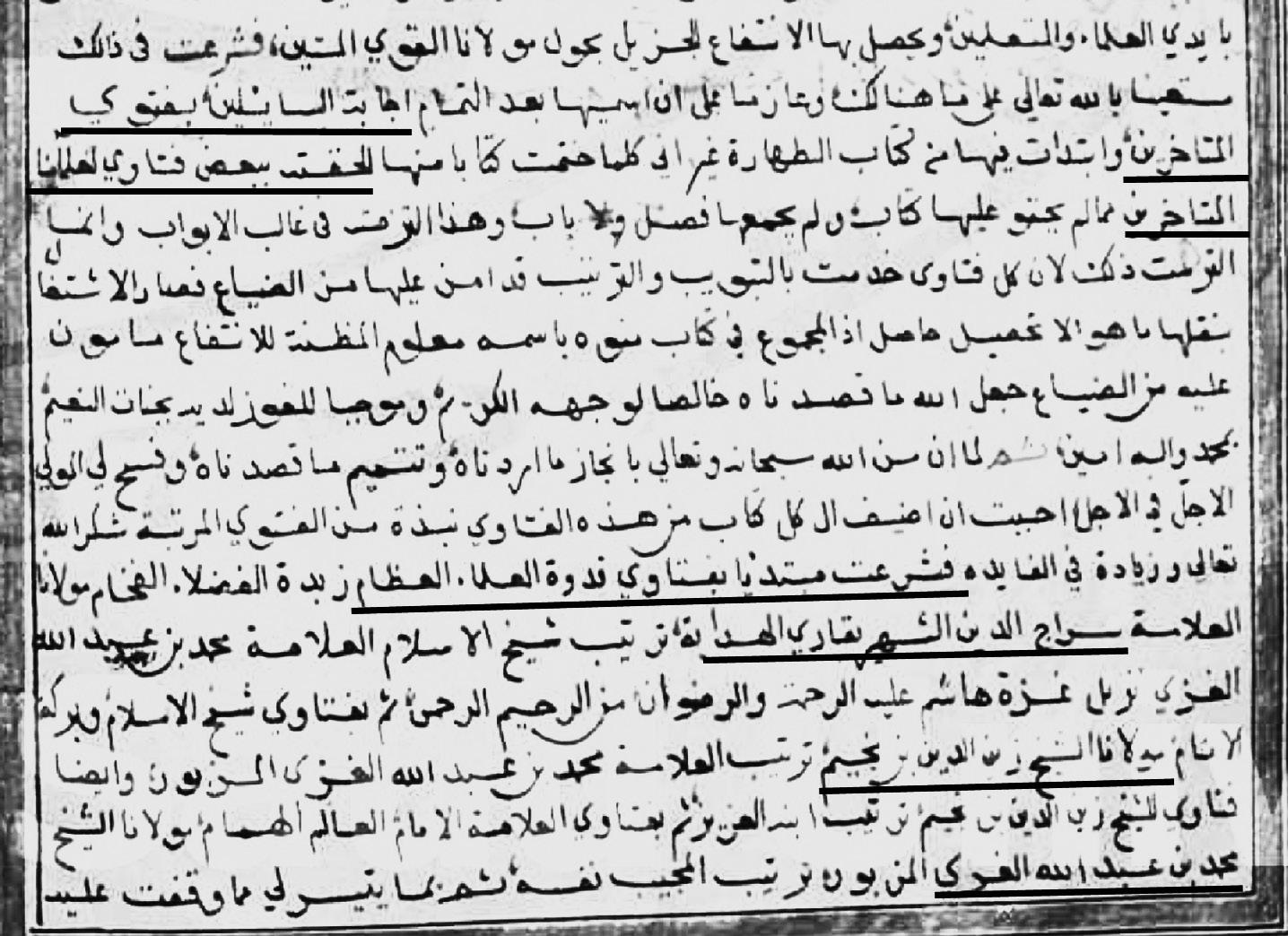

Moreover, the label “late Ḥanafīs” is also employed in the early modern period in relation to the authority to respond to legal questions. Jamāl al-Dīn al-Ḥānūtī (d. 1601), for example, authored a work titled Ijābat al-Sāʾilīn bi-Fatwā al-Mutaʾakhkhirīn (Answering the questioners on the basis of the fatwā of the late Ḥanafīs; see Figure I.3). The work was collected and arranged by ʿAbd Allāh b. Ḥasan al-Kāzrūnī (d. 1690?), who states in the introduction that he relied

28 Al-Laknawī mentions these versions of the name. He elaborates that al-Ḥulwānī refers to Ḥulwān, a small town, whereas al-Ḥalwāʾī denotes someone who sells ḥalwā (dessert).

29 ʿAbd al-Ḥayy al-Laknawī, ʿUmdat al-Riʿāya, 15–16; al-Laknawī, al-Fawāʾid al-Bahiyya fī Tarājim alḤanafīyya (Beirut: Dār al-Maʿrifa, n.d.), 241.

30 Baber Johansen, The Islamic Law on Land Tax and Rent: The Peasants’ Loss of Property Rights as Interpreted in the Hanafite Legal Literature of the Mamluk and Ottoman Periods (London: Croom Helm, 1988), 98.

31 Ibid.

32 Muḥammad b. ʿAlī b. Aḥmad b. Ṭulūn al-Sāliḥī al-Dimashqī, al-Ghuraf al-ʿAliyya fī Tarājim Mutaʾakhkhirī al-Ḥanafīyya (MS, Süleymaniye, Şehit ʿAlī Paşa, 001925 [368 fols.]), fol. 2a.

33 Guy Burak alerted me to the fact that Ibn Ṭulūn appears to be responding to other works on the mutaʾakhkhirīn in the Shāfiʿī school, namely, Bahjat al-Nāẓirīn ʾila Tarajim al-Mutaʾakhkhirīn mina al-Shāfiʿiyya al-Bāriʿīn by Muḥammad b. Aḥmad b. ʿAbd Allāh al-Ghazzī (d. 864/1459).

34 Ibn Ṭulūn, al-Ghuraf al-ʿAliyya, fol. 2a.

Figure I.2 Ibn Ṭulūn al-Dimashqī, al-Ghuraf al-ʿAliyya, fol. 1a.

Figure I.3 Al-Ḥānūtī, Ijābat al-Sāʾilīn bi-Fatwā al-Mutaʾakhkhirīn, fol. 2b.

primarily on the fatāwā of the late Ḥanafīs.35 He informs us that he arranged al-Ḥānūtī’s fatāwā thematically in accordance with the organization of books of jurisprudence. At the end of each chapter, al-Kāzrūnī dedicates a special section to a list of the late Ḥanafī fatāwā on that chapter’s topic.36 However, the most significant aspect of this work is its sources. Al-Kāzrūnī incorporates a body of fatwā literature that represents what he calls “the late Ḥanafī opinions.”37 He includes the fatwā works of Sirāj al-Dīn ʿUmar b. ʿAlī b. Fāris al-Kinānī al-Ḥanafī, known as Qāriʾ al-Hidāya (d. 1426),38 and of Zayn al-Dīn b. Ibrāhīm b. Nujaym (d. 1562–3).39

Importantly, these two scholars were Egyptians, and their scholarship had a lasting influence on Ottoman Ḥanafism. Ḥanafī networks in Egypt (as well as in Syria) provided the educational training and scholarship for emerging Anatolian Ottoman Ḥanafī jurists. Prominent Anatolian Ottoman Ḥanafīs traveled to Egypt and Syria for legal education. A few examples of such scholars are Dāwūd alQayṣarī al-Kurāmānī (d. 1350), Muḥammad b. Isrāʾīl b. ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz, known as Ibn Qāḍī Samāwnih (d. 1420), and Shams al-Dīn al-Fanārī (d. 1431).40

Furthermore, Ḥanafī jurists from Ibn Nujaym to Ibn ʿĀbidīn employ a number of specific phrases to show the fully developed nature of their identity, opinions, and consensus in relation to those of the early Ḥanafīs. These phrases include ajmaʿa al-mutaʾakhkhirūn (“the late Ḥanafīs agreed on”), ikhtalafa almutaʾakhkhirūn (“the late Ḥanafīs differed among themselves on”), ṭāʾifa min al-mutaʾakhkhirīn (“a group of the late Ḥanafīs”), ʿāmmat al-mutaʾakhkhirīn (“the majority of the late Ḥanafīs”), baʿḍ al-mutaʾakhkhirīn (“some/one of the late Ḥanafīs”), kathīr min mashāyikhinā al-mutaʾakhkhirīn (“many of our late Ḥanafī master scholars”), jamāʿa min al-mutaʾakhkhirīn (“many of the late Ḥanafīs”), ikhtiyār al-mutaʾakhkhirīn (“the preference of the late Ḥanafīs”), al-mukhtār ʿinda al-mutaʾakhkhirīn (“the preferred opinion among the late Ḥanafīs”), shawādh baʿḍ al-mutaʾakhkhirīn (“legal opinions among the late Ḥanafīs that fall beyond the accepted boundaries of the school”), akthar al-mutaʾakhkhirīn (“most of the late Ḥanafīs”), al-madhhab ʿinda al-mutaʾakhkhirīn (“the authentic opinion of the late

35 Muḥammad b. ʿUmar al-Ḥānūtī, Ijābat al-Sāʾilīn bi-Fatwā al-Mutaʾakhkhirīn (MS, King Saud University, J 3018 [204 + 106 fols., copied ca. 1118/1706]), fol. 2b.

36 Ibid. 37 Ibid.

38 The formal legal opinions of Qāriʾ al-Hidāya were collected by his disciple Kamāl al-Dīn b. alHumām al-Ḥanafī (d. 1457). The collection contains juridical questions posed by a judge and the answers provided by Qāriʾ al-Hidāya. A similar compilation was also collected and arranged by Muḥammad al-Ghazzī al-Timurtāshī (d. 1596).

39 Muḥammad al-Timurtāshī also collected and arranged Ibn Nujaym’s fatāwā. Al-Timurtāshī’s legal scholarship enjoyed immense authority among Ḥanafīs in the sixteenth through nineteenth centuries.

40 See Aḥmad b. Muṣṭafā Ṭaşköprüzāde, al-Shaqāʾiq al-Nuʿmāniyya fī ʿUlamāʾ al-Dawla al-ʿUthmāniyya (Beirut: Dār al-Kitāb al-ʿArabī, 1975), 8, 12, 16. The centrality of the Egyptian Ḥanafī tradition is also affirmed by the sources used by the Damascene Ḥanafī jurist Muḥammad Amīn b. ʿĀbidīn (d. 1836) in his legal commentary. In his introduction to his famous commentary Radd al-Muḥtār, Ibn ʿĀbidīn enumerates the important authorities among the late Ḥanafīs who shaped his commentary. The Mamluk-era Egyptian Ḥanafī Ibn al-Humām and his students Ibn Amīr Ḥājj (d. 1474) and Qāsim Ibn Quṭlūbughā (d. 1474) are central to late Ḥanafism in the Ottoman period.