https://ebookmass.com/product/law-and-love-in-ovid-courting-

Instant digital products (PDF, ePub, MOBI) ready for you

Download now and discover formats that fit your needs...

Law, Courts, and Justice in America

https://ebookmass.com/product/law-courts-and-justice-in-america/

ebookmass.com

Love and Marriage in the Age of Jane Austen Rory Muir

https://ebookmass.com/product/love-and-marriage-in-the-age-of-janeausten-rory-muir/

ebookmass.com

Philosophy in Ovid, Ovid as Philosopher Gareth D. Williams (Editor)

https://ebookmass.com/product/philosophy-in-ovid-ovid-as-philosophergareth-d-williams-editor/

ebookmass.com

Presupuestos: Planificacion y Control 6th Edition Glenn A. Welsch

https://ebookmass.com/product/presupuestos-planificacion-ycontrol-6th-edition-glenn-a-welsch/

ebookmass.com

Placebo effects : understanding the other side of medical care 3rd Edition

Fabrizio Benedetti

https://ebookmass.com/product/placebo-effects-understanding-the-otherside-of-medical-care-3rd-edition-fabrizio-benedetti/

ebookmass.com

Qualitative Methodologies in Organization Studies: Volume I: Theories and New Approaches 1st Edition Malgorzata Ciesielska

https://ebookmass.com/product/qualitative-methodologies-inorganization-studies-volume-i-theories-and-new-approaches-1st-editionmalgorzata-ciesielska/ ebookmass.com

Liberation, (De)Coloniality, and Liturgical Practices: Flipping the Song Bird 1st ed. Edition Becca Whitla

https://ebookmass.com/product/liberation-decoloniality-and-liturgicalpractices-flipping-the-song-bird-1st-ed-edition-becca-whitla/

ebookmass.com

Time Series Analysis in Seismology: Practical Applications 1st Edition Alejandro Ramírez-Rojas

https://ebookmass.com/product/time-series-analysis-in-seismologypractical-applications-1st-edition-alejandro-ramirez-rojas/

ebookmass.com

Britain and Danubian Europe in the Era of World War II, 1933-1941 (Britain and the World) 1st ed. 2021 Edition

Andras Becker

https://ebookmass.com/product/britain-and-danubian-europe-in-the-eraof-world-war-ii-1933-1941-britain-and-the-world-1st-ed-2021-editionandras-becker/

ebookmass.com

https://ebookmass.com/product/breaking-ground-from-extraction-boomsto-mining-bans-in-latin-america-rose-j-spalding-2/

ebookmass.com

1

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP, United Kingdom

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries © Ioannis Ziogas 2021

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

First Edition published in 2021

Impression: 1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Data available

Library of Congress Control Number: 2020942394

ISBN 978–0–19–884514–0

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780198845140.001.0001

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. Oxford disclaims any responsibility for the materials contained in any third party website referenced in this work.

For Daphne

incipe, parua puella, patrem cognoscere risu

Preface

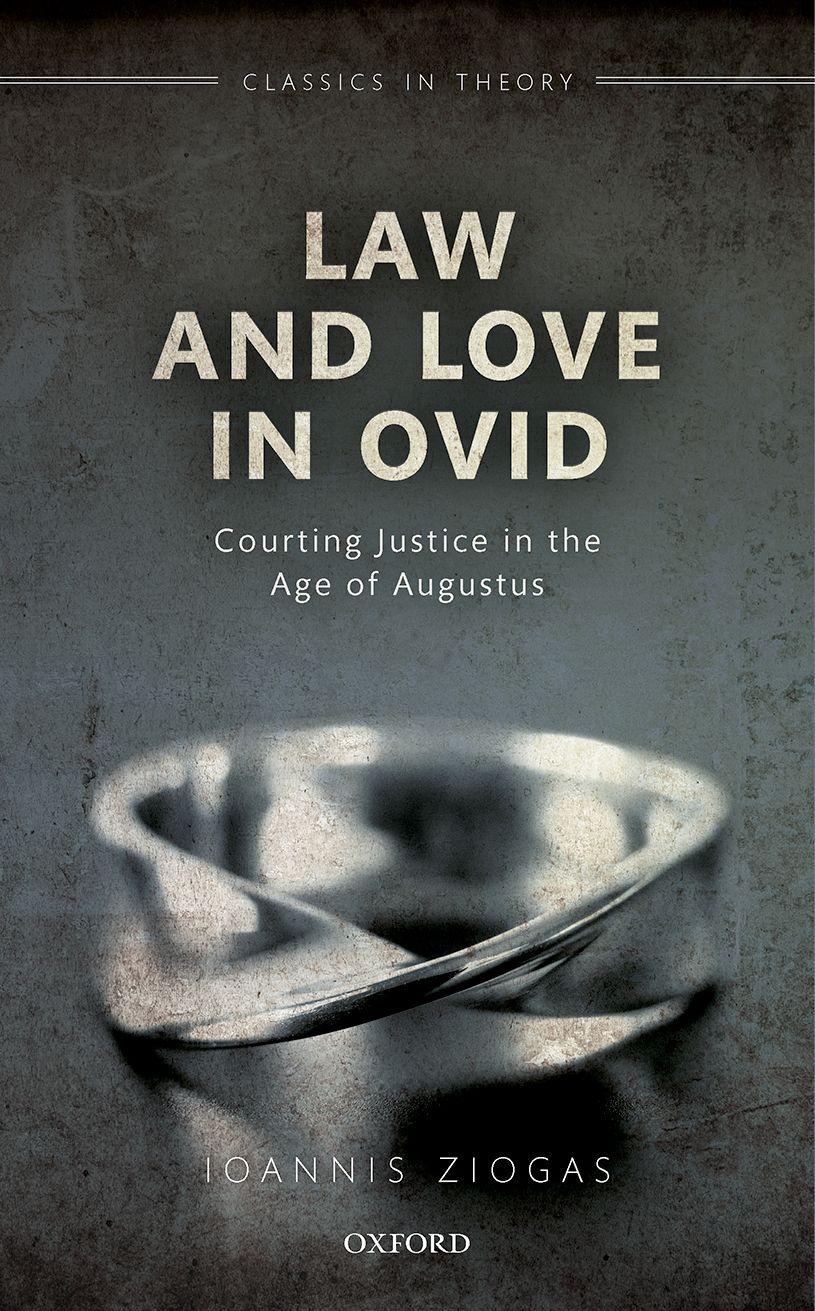

This book’s cover shows a wedding ring in the shape of a Möbius band. Such rings have become fashionable, though I am sure their popularity has nothing to do with the contents of this book. Nevertheless, the image illustrates one the main theoretical approaches of this monograph. Giorgio Agamben (1998: 37–8) mentions the Möbius strip in his attempt to represent schematically the essence of sovereignty. For Agamben, sovereign power is the very impossibility of distinguishing what lies inside and outside the law; rule and exception, nature and law, violence and justice pass through one another as in a Möbius strip. My argument is that the relationship between law and love in Latin love elegy creates a similar zone of indistinction between what lies inside (law) and outside (love) the juridical order. This is how Amor emerges as the sovereign legislator of elegiac love. At first sight, the relationship between law and love may look antithetical. Love falls outside or transcends legal boundaries—it is above or beyond the law. The law, by contrast, needs to suppress affection in order to operate objectively. We may represent love (extramarital and extralegal) and law (family and property law) with two distinct circles. When emotions (love or anger) enter the legal sphere, they signal a suspension of proper procedure, an exception to the rules. But instead of undermining the law, many exceptions are fundamental to the legal system (think of clementia1 or amnesty). The exception and the rule are mutually constitutive. Thus, in the next stage, the two circles of law and love are inside each other—they form two concentric circles that overlap in part. In the third stage, the exception (love) and the rule (law) merge in one circle. Marriage is a good example of how law and love may or

1 Clementia is the sovereign’s power to pardon someone who deserves to be convicted. In Seneca’s De clementia, it appears predominantly in contexts of imperial adjudication, but is an extrajudicial action. It is the power to suspend the law in the name of justice.

should coincide in absolute indistinction. And the Möbius band is what illustrates the union of lex (‘law’) and amor (‘love’).

This book argues that Ovid is obsessed with the interactions between law and love—the ways in which these concepts can be perceived as mutually exclusive but also mutually constitutive, as distinct and inseparable. My aim is to study what Ovid has to say about this dynamic dialectic. This does not mean that I necessarily endorse his ideas (and thus I hope that I will not be relegated to the margins of scholarship). Although I am passionate about Ovid, I intend to neither approve nor disapprove of his amatory jurisprudence. Between the roles of Ovid’s defence lawyer and prosecutor, I choose neither.

Admittedly, this may be hard to achieve, given that the trial setting, where Ovid defends his life and poetry, is one of his main preoccupations. In Ovid’s case, a iudex is simultaneously a judge and a literary critic. Aesthetics and legality, like law and love, blend together at the moment of their separation. Ovid loves a good courtroom drama. But despite his burning desire to be part of legal procedures, he has been convicted, censored, or acquitted without trial from his to our times. There is something in his poetry that turns readers into judges, and, in my view, this is not coincidental, but lies at the heart of his oeuvre; his love poetry is essentially juridical, inviting readers to pass judgment on its principles. Is Ovid a sexist or a feminist? Does he support or undermine Augustus’ laws? Is he guilty or not guilty? Do his laws of love liberate or enslave?

I do not have a straightforward answer to these questions other than that one can argue either side. The main point is that in Love’s sovereign rule, the identities of master and slave, moralist and adulterer, lawgiver and outlaw become indistinguishable. Once we put Amor in the dock, we realize that he is a very elusive god—he is both a lovely child and a venomous creature; he can reconcile or divide; he likes to live outside the law, but is fully versed in it. Amor in the Ovidian sense covers a great range of emotions and behaviours, a fact that made my research both challenging and fascinating. Love may aim to establish a harmonious society in which justice is so prevalent that crimes are non-existent and thus legal procedures are suspended indefinitely. The laws of love are the dream of a utopian

civilization. In its positive connotations, Ovid’s amor is not unrelated to the Christian meaning of love as the fulfilment of the law—I do not shy away from the tradition of a ‘Christian Ovid’ (Ouidius Christianus). In particular, I draw a connection between Ovid’s laws of love and the Judaeo-Christian tradition of the relationship between law and love (especially as it is expressed in Paul’s letter to the Romans).

But this is not the whole story of amor in Ovid. Elegiac love is synonymous with crimen (‘accusation’ or ‘crime’). Amor can be tyrannical. His sovereignty thrives in a state of exception, which blends violence and justice, coercion and persuasion, nature (φύσις) and custom (νόμος). This coincidence of opposites casts a dark shadow on Amor’s regime. The very exceptionalism of the rule of Love takes us to the origins of totalitarianism. In particular, the ways in which Amor construes his sovereign jurisdiction uncannily reflect the ways in which the emperor Augustus established his autocratic rule, namely by simultaneously setting himself inside and outside the juridical order. The prince is primus inter pares (“first among equals”), both included in a legislative body as an equal member and standing outside it as the undisputable first in the hierarchy.

My thesis is that Ovid deploys legal discourse throughout his works in conscious reflection on Augustus’ ongoing—and thoroughgoing— revision of the Roman legal landscape. To that end, I select representative case studies from the whole of Ovid’s oeuvre, from the Amores, Heroides, Ars amatoria, and Remedia amoris to the Metamorphoses, the Fasti, and the exile poetry. The passages I discuss are wideranging, but far from exhaustive. Ovid’s poetry is so deeply steeped in the language and rituals of law that it is hard to find a substantial passage that does not engage with legal theory or practice. I hope that my work will inspire further study on Ovid and the law, but also make a significant contribution to the interdisciplinary field of law and literature. This book is not the fulfilment of Ovid’s laws of love—it is just the beginning.

Acknowledgements

Parts of significantly revised versions of three of my previous publications are included in this book. The first part of ‘Stripping the Roman Ladies: Ovid’s Rites and Readers’, Classical Quarterly 64 (2014), 735–44 has been reworked for Chapter 6; ideas and arguments from ‘Love Elegy and Legal Language in Ovid’, in P. Mitsis, and I. Ziogas, (eds.) Wordplay and Powerplay in Latin Poetry, De Gruyter, Berlin and Boston, MA, (2016) 213–40 are developed in Chapters 2, 4, and 6; Chapter 8 has substantial points of contact with ‘Orpheus and the Law: The Story of Myrrha in Ovid’s Metamorphoses’, Law in Context 34 (2016), 24–41. These publications are not simply reproduced—they have been thoroughly revised and integrated into the structure and overall approach of the monograph. Significant parts of these articles are not included in this book, and thus the publication of this monograph does not replace them. I would like to thank the editors of Classical Quarterly, Law in Context, and De Gruyter’s series Trends in Classics for permission to reprint revised parts of my previous work.

I often consulted the Loeb translations of Greek and Latin texts. Several translations in the book are modified versions of Loeb translations. For the titles of Greek and Latin texts, I follow the abbreviations used in the Oxford Classical Dictionary.

The idea of this book was conceived when I was working in the Australian National University. I am grateful to Renata Grossi for inviting me to contribute to Law in Context’s special volume on ‘Law and Love’. Desmond Manderson was incredibly supportive at the very beginning of my project. He has inspired a great part of my work, and I owe him more than he probably realizes.

I thank Durham University for granting me a term of research leave to work on this book (Epiphany 2018). I am very grateful to Durham’s Department of Classics and Ancient History— their support and encouragement kept me going. I feel very lucky to be part

xii Acknowledgements

of such a collegial group of scholars. I am particularly grateful to Jennifer Ingleheart, Zara Chadha, Peter Heslin, Roy Gibson, Erica Bexley, Amy Russell, Phillip Horky, Stuart McKie, and Ted Kaizer. I would also like to thank James McKeown for sending me a draft of his unpublished commentary on Amores 3.

My students at Durham have been a source of inspiration for this project. I am grateful to all the students who took my module on Roman Law and Latin Literature and my MA seminar on Law and Literature in Ancient Greece and Rome. That was research-led teaching at its best.

I presented various parts and versions of this book at the Universities of St. Andrews, Edinburgh, Cambridge, Belgrade, Newcastle, Boston, the Scuola Normale Superiore in Pisa, and the Florida State University. I am grateful to colleagues who invited me to present my work and to audiences for their responses. I am particularly grateful to Nikoletta Manioti, Aaron Pelttari, Goran Vidović, Athanassios Vergados, Leah Kronenberg, Hannah ČulíkBaird, Patricia Johnson, Gianpiero Rosati, and Celia Campbell.

Many thanks to Oxford University Press and the series editors of Classics in Theory for being extremely supportive from the beginning till the end. I am particularly grateful to my OUP editors, Georgina Leighton and Karen Raith, and their excellent team. Many thanks are also due to the anonymous readers of the press for their perceptive, detailed, and challenging reports.

I would also like to thank my friend George Gryllos, who took the picture of the book cover.

If the book’s iudices discover any faults or misdemeanours in my work, I take full responsibility—ego feci!

1 Introduction

Eros and Nomos

We may start by saying that law is the negation of passion. As Aristotle put it, ‘the law is a mind without desire’ (Politics 3.11.4

ἄνευ ὀρέξεως νοῦς ὁ νόμος ἐστίν). The legal system relies on dispassionate objectivity in an attempt to put an end to the vicious circle of revenge. Personal desires and vendettas need to be controlled by the disinterested hand of the law. Subjective emotions undermine law’s rationality. Vengeance does not end crime but perpetuates it in a way that renders the distinction between crime and punishment indistinguishable. Reason is the source of the law and passion a regression to the primitive rules of the lex talionis (‘law of retaliation’). The representatives of the legal system need to be unrelated to their subjects. It is imperative for the effective administration of justice that the judge have no relationship with the defendant outside the strictly prescribed rituals of the courtroom.

Yet we can also argue that desire is the ultimate source of the law. The legal system does not replace passions with reason, but creates an elaborate apparatus that conceals the very source of justice, which is none other than the will of the legislator. Law needs a precedent in order to establish its objectivity. Every law acquires authority from past laws, a technical procedure designed to check the transgressive forces of personal urges. But once we strip law of all layers of referentiality, we are left with the arbitrary choices of the legislator or the will of a god. No rational explanation can justify the primary source of law, unless it includes the subjectivity of the legislating authority. If we push this argument further, we can even say that law is the division of passions into legitimate and illegitimate.

Law and Love in Ovid: Courting Justice in the Age of Augustus. Ioannis Ziogas, Oxford University Press (2020). © Ioannis Ziogas.

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780198845140.003.0001

Similarly, love poetry is often a normative discourse that legitimizes or outlaws desire. That the language of pleasure dominates love poetry may seem unremarkable. More surprising is that pleasure is explicitly related to the lawmaking procedures of the Romans. The legislative formula senatui placuit (‘it pleased the senate’) reveals an often wellhidden secret: that the ultimate source of law is the desire of the legislator. Under Augustus, this sovereign authority is transferred to the prince. Ulpian famously rules that ‘whatever pleased the prince has the force of law’ (Institutes 1.4.6; Digest 1.4.1 quod principi placuit legis habet uigorem). In the numerous constructions of placet (‘it is pleasing’) in Ovid, we should detect the poet’s claim to the authority of the sovereign legislator. Ovid exemplifies the confluence of lawmaking and lovemaking, an essential aspect of his poetry that has been overlooked in scholarship.

Latin love elegy reaches its climax at the same time as Augustus introduces his moral legislation. This is not a coincidence. The production of laws that revolve around the regulation of sexuality and the publication of love poetry that has the force of law are the two sides of the same coin. Augustus’ reforms were unprecedented in the history of Roman law. His legislation criminalized adultery, encouraged marriage, rewarded childbirth, and penalized celibacy.1 What was hitherto the business of the family and the pater familias now became the business of the state and the pater patriae. For the first time, a standing criminal court was created to punish adultery and criminal fornication by trial. The laws were primarily aimed at the upper classes, whose members, in the eyes of Augustus, had deviated from the good old ways of Republican morality. To this end, there were several legislative attempts: the Lex Iulia de maritandis ordinibus (18 bce ), the Lex Iulia de adulteriis coercendis (16 bce ), and the Lex Papia Poppaea (9 ce ). This time span is indicative of Augustus’ persistence and struggle to enforce a particularly unpopular legislative agenda. Despite the immediate reaction from several groups (including the knights, Ovid’s social class), the laws remained valid for centuries. Yet they did not seem to be successful, if we trust

1 On Augustus’ moral legislation, see Csillag (1976); Raditsa (1980); Treggiari (1991); Edwards (1993: 34–62); McGinn (1998: 140–215).

Tacitus (Annales 3.25) and Dio (56.1–10).2 A particularly thorny issue was that Augustus himself suffered under his laws. The prince punished his daughter and granddaughter for committing adultery. His family life was too problematic to function as an authoritative example for his marriage legislation. Augustus (then Octavian) divorced Scribonia soon after she gave birth to his daughter Julia to marry a hastily divorced and heavily pregnant Livia. Rumours about Augustus committing adultery with Livia before their marriage would inevitably proliferate.

Ovid (43 bce –17 ce ) writes his love poetry during this period. Even though we are not sure about the date of the second edition of his Amores, it is beyond reasonable doubt that the love poet is aware of the Augustan legislation. The moral reforms loom large throughout Ovid’s oeuvre, not only in his love elegies (the Amores, the Heroides, the Ars amatoria, and the Remedia amoris), but also in the Metamorphoses, the Fasti, and the exile poetry (the Tristia and Epistulae ex Ponto). The Ars amatoria is a turning point, since it is likely that it provided a reason for Ovid’s exile in 8 ce . On account of ‘a song and a mistake’ (Tristia 2.207 carmen et error), the poet was relegated to Tomis by a decree of Augustus. The measure is extraordinary; the emperor was personally offended by Ovid. In his exile poetry (e.g. Tr. 5.12.67–8; Ibis 5–6), Ovid says that he was destroyed by his own art (meaning his poetic art but also his ‘Art of Love’)— his books are compared to children who turned against their father (see Chapter 7). There is an uncanny similarity here between Ovid, the author of love poetry, and Augustus, the author of moral legislation—the prince suffered under his own laws when his own child broke them.

The similarities between Ovid and Augustus are a key aspect of this book. In my view, Ovid is essentially antiAugustan not in his opposition to the prince, but in his attempt to be equal to Augustus (the other meaning of the Greek ἀντί). This is important for interpreting legal discourse in Ovid. The love poet does not simply ‘comment on’ the laws of Augustus, but casts himself in the role of the sovereign legislator. And even if Ovid’s poetry simply reacts to

2 For the minority view that Augustus’ laws could be judged successful, see Reid (2016).

Augustan legislation, this is not a superficial reaction. To interpret the law was a legislative act in the age of Augustus. The interpretations of influential jurists were instrumental for the production of law. As we shall see in this book (Chapter 6), Ovid casts himself as a jurist—the teacher of law and the teacher of love speak the same language. Far from reducing literature to a harmless parody of real law, we need to take seriously the ways in which Ovid’s love poetry is involved in the production of normative discourse.

While scholars relegated Ovid to the realm of mockery and frivolity, my book aims to restore him to his rightful position in the field of law and literature. Contrary to Kenney’s (1969: 263) view that Ovid’s transference of legalisms into elegy is surprising and amusing, I argue that the language of law in Ovid is not incidental, but fundamental. If older critics may be excused, antiquitatis causa, for dismissing legal language in Ovid as superficial and incongruous (see, e.g. Daube 1966; Kenney 1969; 1970), the persistence of similar views in more recent scholarship shows that more often than not there is still no escape from the interpretative dead end of trivializing Ovid. In an otherwise fine and compelling article, Kathleen Coleman (1990: 572) suggests that Ovid imitates the pedantic locutions of jurists in order to trivialize the preoccupations of the bickering Olympians. For Coleman, legal jargon in Ovid contributes an atmosphere of incongruous pomposity to the divine comedy of the Metamorphoses. She notes that ‘[it] has been well observed that Ovid frequently employs legal terminology in contexts where it is either starkly incongruous or else pregnant with double entendre’. Coleman here subscribes to Kenney’s reading. Similarly, Alessandro Schiesaro (2007: 82), in his perceptive chapter on rhetoric and law in Lucretius, endorses Kenney’s view that legal terminology in Ovid points to little more than his training in eloquence. For Neil Coffee (2013: 85), the lover’s juridical discourse in Amores 1.10 is evidence that Ovid was more concerned with the rhetorical play of his poetry than with the representation of a real amatory situation (as if we could strip away from a ‘real amatory situation,’ whatever that means, all layers of rhetoric). ‘Few lovers’, he adds, ‘would have been clever enough to know something about the law and dull enough to imagine that they could persuade their girlfriends with legal

analogies.’ Without further ado, the lover’s discourse is deemed alien to anything that has to do with the law. To introduce legal diction into love poetry is to highlight an absurd combination.

This book argues against the widespread view that the language of law in Ovid is another glib affectation of our poet. In my view, the image of a superficial Ovid is the creation of superficial scholarship. I do not mean to argue that Ovid’s poetry is not playful (far from that). Something can be fundamental and important—even, in sense, serious—but still amusing. Ovid’s playfulness should not prevent us from exploring the deeprooted connections between law and love. Below the glimmering surface of Ovid’s wit there is an ocean of amatory jurisprudence.3 Even if the language of law in Ovid is another joke, this should not be the end but the starting point of our interpretations. We do not really get the joke, unless we figure out what is at stake in it. And what is at stake is much more than mockery of the Augustan legislation. What is at stake is a fearless exploration of the origins of law.

My thesis is that the language and rituals of law in Ovid point to love as the source of the law’s emergence. This may sound like the sort of trendy legal theory that has little to do with Ovid. In fact, it comes from Ovid’s poetry. In Fasti 4, for instance, the book and month of Venus, Ovid includes an encomium of the goddess of love. Venus is praised as the lawgiver of the universe (Fasti 4.93 iuraque dat caelo, terrae, natalibus undis, ‘and she gives laws to the sky, the earth, and her native sea’). The goddess of love is thus the primary legislator. For Ovid, Venus is the origin of human civilization:

prima feros habitus homini detraxit: ab illa uenerunt cultus mundaque cura sui. primus amans carmen uigilatum nocte negata dicitur ad clausas concinuisse fores, eloquiumque fuit duram exorare puellam, proque sua causa quisque disertus erat.

3 Contra Miller (2004: 162): ‘What lies beneath the surface of Ovidian wit is precisely nothing.’

mille per hanc artes motae; studioque placendi, quae latuere prius, multa reperta ferunt.

Ovid, Fasti 4.107–14

That force first stripped man of his savage garb; from her he learned decent attire and personal cleanliness. A lover was the first, they say, to serenade by night the mistress who denied him entrance, while he sang at her barred door, and eloquence lay in winning over a harsh girl, and each man was a barrister pleading his cause. This goddess has been the mother of a thousand arts; the wish to please has given birth to many skills that were unknown before.

In the context of the laws of Venus, the passage quoted above evokes the setting of a trial: the primary meaning of causa is ‘a legal case’ (OLD s.v. A1) and disertus means ‘barrister/forensic orator,’ as in Ovid, Ars amatoria 1.85 (see Hollis 1977: 49–50 and cf. Ars 1.459–64). Readers familiar with Latin love elegy will recognize that Venus here features as the inventor of this genre. The lover’s serenade (109–10), the socalled paraclausithyron (‘lament by the door’), is a trademark of the elegiac lover. The role of Venus also clearly evokes the praeceptor amoris (‘the teacher of love’) of the Ars amatoria. Instructions about cultus (‘fashion style’) and munditia (‘cleanliness’) feature in the Ars amatoria. Winning over a girl is similar to wining over a judge (cf. Ars 1.459–64). The pursuit of pleasure, the aim of the Ars amatoria, is the origin of a thousand artes. These ‘arts’ are inspired by Venus and derive from the art of love. The art of rhetoric, ars oratoria, is cast as an imitation of the art of love, ars amatoria. This is important for understanding how Ovid conceives of the relationship between the lover’s and the lawyer’s discourse. Contrary to modern critics who see incongruity between the language of law and love, Ovid points to Venus as their common origin. For Ovid, forensic rhetoric derives from the poetics of Latin love elegy. In Ovid’s history of human civilization, the art of courtship not only precedes courtroom rhetoric, but actually provides the model for winning a legal case. Fasti 4.111–12 is not a case of introducing the setting of a trial into the rituals of elegiac courtship, but exactly the opposite. The elegiac lover is the archetypal lawyer (disertus). From that

perspective, the current practice of pointing out Ovid’s borrowings from law is problematic. Ovid says that legal diction is a reflection of the lover’s discourse, not the other way around.

Far from being an Ovidian peculiarity, the overlap between amatory and forensic discourse is as old as Homer and Hesiod.4 The end of Aeschylus’ Eumenides, to refer to a clearly serious case, is a good example for the confluence of legal and amatory persuasion. Nicholas Rynearson (2013) argues convincingly that Athena draws on the discourse of amatory persuasion in order to win over the Erinyes to give up their wrath. Through the erotic element of her seductive speech, the virgin goddess woos the Erinyes, casting them as the beloved objects. Her rhetoric of seduction has a transformative power over the Erinyes, just as amor is the driving force of metamorphoses. Critics have been puzzled by the fact that no less than onethird of the play takes place after the decision has been rendered. But Aeschylus seems to understand that the legal system does not depend on whether the winners accept the verdict, but on whether the losers do.5 To sustain the law, seductive persuasion is more fundamental than law enforcement.

My work contributes to a current interdisciplinary trend in law and the humanities that examines the interactions between law and love.6 Peter Goodrich (1996; 1997; 2002; 2006) has been a pioneer in this field and one of the main inspirations for my project. Justice, Goodrich (2006: 7) notes, has always been tied to the jurisdiction of love. The law of Venus was the originary and thus higher law, because it allowed for settlement, and it furthered the community in mending itself. To proceed by love was to remain friends and to forestall law in its coercive and punitive forms (see Goodrich 2006: 8). We shall see that Ovid draws a similar distinction between the justice of love and the corruption of litigation, between love that resolves conflict and legalism that breeds dissent (see Chapter 5).

4 See Chapter 5. On amatory persuasion in antiquity, see Gross (1985).

5 Cf. Ovid, Tr. 2.95–6 (discussed in Chapter 5), in which the poet refers to his appointment as a judge and tells Augustus that even the losing side acknowledged his good faith.

6 See Bankowski (2001), who argues that law and love are entangled and even dependent on each other. See also Detmold (1996); Petersen (1998); Goodrich (1996); (2006); Manderson (2003); Meyer and Umphrey (2010); Nussbaum (2013); Grossi and Neoh (2016); Neoh (2019). On law and love in Shakespeare, see Kahn (2000); in Cervantes, see González Echevarría (2005).

While Goodrich mentions Ovid in passing, the Roman poet is at the centre of my research. The medieval tradition that Goodrich studies is not anomalous in time, unrelated to prior or succeeding legal discourses. In fact, a great part of it derives from the Ovidian jurisprudence of love.7

My work both builds on Goodrich and interrogates his approach. The key is that Goodrich treats the medieval courts of love as isolated from the mainstream legal system and running by wholly independent norms. By contrast, my aim is to show that Ovid’s courts of love were not simply ‘other’ than Roman law but fundamentally connected to them in discourse, in principles, and in concepts of jurisdiction. The engagement between love and law is intimate rather than isolate, and this makes a contrast with Goodrich’s approach.

Interdisciplinary work on law and the humanities has reopened questions of jurisdiction and the plurality of laws—nterior and exterior, emotional and rational, imagined and real. All these issues lie at the heart of Ovid’s poetry; yet Ovid is conspicuously absent from recent work on law and literature. By contrast, scholarship on Ovid rarely engages with current developments in legal theory. The common denial to take law in Ovid seriously is partly to blame for this. There are, however, some exceptions which hopefully suggest a paradigm shift. In his book on Latin love elegy, Paul Allen Miller (2004: 160–83) includes a chapter on ‘Law and the Other in the Amores’. He argues that Ovid’s Amores revolve around the double axis of law and transgression. His fascinating argument is relevant to my thesis that Ovidian elegy creates a zone of indistinction between following and breaking the law (see Chapter 3). Miller argues that Ovid violates the law in such a way as to require its preservation. For Miller, the poet ultimately reproduces the structures of the dominant regime. Without law there is no transgression, and vice versa. In my view, Ovid indeed avers that transgression is the fulfilment of the law. But the fulfilment of the law can be either its

7 Andreas Capellanus’ Rules of Courtly Love (twelfth century), Boccaccio’s Decameron (fourteenth century), Martial d’Auvergne’s Judgments of Love (fifteenth century), and Stephanus Forcadel’s Cupido Jurisperitus (sixteenth century) are deeply influenced by Ovid’s amatory jurisprudence.

preservation or its end. While imperial legislation crumbles in Ovid’s sovereign jurisdiction of love, the art of love cannot escape from the web of Augustan legislation.

Micaela Janan (2001: 146–63) has a short, but perceptive analysis of the interdependence of law and desire in Propertius 4.11.8 Janan applies Lacan’s concept of the Law as ungrounded in any unshakable foundation to her compelling reading of Livy’s Verginia and Propertius’ Cornelia. She notes that ultimately juridical reasoning comes to rest in the logical opacity of desire: something is made into law, because ‘it is the will of [the gods, Nature, emperor, people, senate]’. To the question ‘what does justify this’, no answer can be given (Janan 2001: 149). Janan’s chapter is relevant to my approach: desire is the ultimate source of law and love. That is why the lover and the legislator are the two sides of the same coin.

Kathryn Balsley’s article on Ovid’s Tiresias (Balsley 2010), which partly derives from her unpublished dissertation (Balsley 2011), discusses Ovid’s presentation of the seer as an expert in law. Ovid brings together prophetic, poetic, and juristic discourse in an era that signals the emergence of the science of law (see Chapter 6). Balsley (2011: 44–100) studies the trial scene in Ovid’s Metamorphoses in a way that complements my work on the trial scene in the Amores, the Heroides, and the Ars amatoria. The trial setting also features prominently in Gebhardt (2009), the only recent booklength study of law in Augustan poetry. This monograph has been extremely useful, as it systematically identifies legal diction in Ovid and other Augustan poets. Yet, despite its usefulness, its scope is limited. Even though Gebhardt (2009: 3–4) mentions in his introduction the field of law and literature, his analysis is mostly restricted to identifying legal terms in Augustan poetry. It is striking that the laws of Augustus do not concern his study.

My book does not follow the common practice of identifying legal terminology in Augustan poetry and then moving on without interpreting its cultural significance. Dissecting legalisms in Ovid

8 I find her discussion of the law of the father in Metamorphoses 3 (Janan 2009: 53–86) less relevant to my approach. Her Lacanian concept of Law is too abstract in comparison to my historically grounded analysis.

for the purpose of collecting and evaluating historical data about Roman law is similarly not the goal of my research. Ovid’s poetry is not merely a reflection or distortion of Roman law but is involved in its production. If the majority of works on Roman law are to blame for studying law as a culturally isolated field, the literary critic who sees legal diction in poetry as appropriated in a closed literary universe falls into a similar trap. In my view, poetry does not borrow from law just to serve poetic ends. Law in literature is more than just another literary device. The language of law in Ovid declares the normative force of his art.

The classicist whose work is most relevant to my project is Michèle Lowrie.9 Her work not only engages with the interdisciplinary field of law and literature, but also combines close readings with historically sensitive analyses. Key aspects of her work (authority, performativity, and exemplarity) feature prominently in my monograph. As far as legal theory is concerned, the work of Giorgio Agamben (1998; 2005a) is key for my argument that both Ovid and Augustus, the love poet and the prince, define the boundaries of the law by excluding themselves from formal legal procedures. For Agamben, sovereignty consists in pronouncing what lies inside and what outside the juridical order. Agamben’s work is not only relevant to Augustan Rome; it actually derives from his research on Roman law and the crucial shift from the Republic to the Principate. The titles of two of his most influential books (Homo Sacer and State of Exception) are concepts of Roman law. According to Pompeius Festus (De uerborum significatione 318), the homo sacer is a man whom anyone can kill without committing a crime. This is an important concept, because it describes a man who is not legally punished, but whom the law banned from the juridical order and thus reduced to what Agamben calls ‘bare life’, a life that does not concern the law. When Latin love poets exclude themselves from the juridical order or are banned from it by a domina (a mistress) or a dominus (Augustus), they bear more than fleeting similarities to the homo sacer (see Chapter 2).

9 See mainly Lowrie (2009: 327–82); (2016).

But they also bear more than fleeting similarities to the sovereign legislator. The homo sacer is a legal creation of tribunician law (see Festus, De uerborum significatione 318). This is important because the sacrosanctity of the tribunes has an uncanny similarity to the bare life of the homo sacer. Augustus solidified his sovereignty by assuming the tribunes’ powers and sacrosanctity (see Chapter 2). The prince becomes the sovereign ruler by creating for himself a state of exception. He simultaneously stands outside the juridical order and belongs to it by legally defining it. My argument is that Latin love poets play a similar game of sovereignty. The elegiac lover exemplifies the correspondence of sovereign power and bare life that lies at the heart of Agamben’s theory. The lover can effortlessly shift roles between an outcast from law and a sovereign legislator, because the homo sacer and the sovereign share a place outside the law. The elegiac poets exclude the sacrosanct lover from the juridical order and thus create a sovereign exception that presupposes the juridical reference in the form of its suspension. In fact, Latin love elegy claimed this state of exception before Augustus. From that perspective, the elegiac constructions of sovereignty are not just a parodic reflection of Augustan politics. Quite the contrary— the prince seems to have copied from Latin love elegy, not the other way around.

Not unlike sovereignty as defined by Agamben, love is included in cultural conventions by excluding itself from them. Love, like law, is a cultural construct that claims that its origins lie outside cultural norms. Cultural constructs are most powerful when they pose as reflections of the natural order. Michel Foucault’s incomplete History of Sexuality (Foucault 1979; 1986; 1988) plays an important role in my research. His work has been both followed and criticized by classicists.10 Some of the criticism is relevant to this book. Foucault skips Augustan Rome, a period that is key for the emergence of sexuality as an independent discourse (cf. Habinek 1997). Contrary to Foucault’s phallocentric approach, Ovid’s poetry and

10 See Hallet and Skinner (1997); Larmour, Miller, and Platter (1998); Nussbaum and Sihvola (2002); Ormand (2008); (2014); Blondell and Ormand (2015); Boehringer and Lorenzini (2016). On Foucault and Roman antiquity, see the collection of articles in Foucault Studies 22 (2017).