https://ebookmass.com/product/law-101-everything-you-need-

Instant digital products (PDF, ePub, MOBI) ready for you

Download now and discover formats that fit your needs...

Cloud Computing with AWS: Everything You Need to Know to be an AWS Cloud Practitioner 1st Edition Pravin Mishra

https://ebookmass.com/product/cloud-computing-with-aws-everything-youneed-to-know-to-be-an-aws-cloud-practitioner-1st-edition-pravinmishra/ ebookmass.com

The New Manager’s Survival Guide: Everything You Need to Know to Succeed in the Corporate World 1st Edition Steven Haines

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-new-managers-survival-guideeverything-you-need-to-know-to-succeed-in-the-corporate-world-1stedition-steven-haines/

ebookmass.com

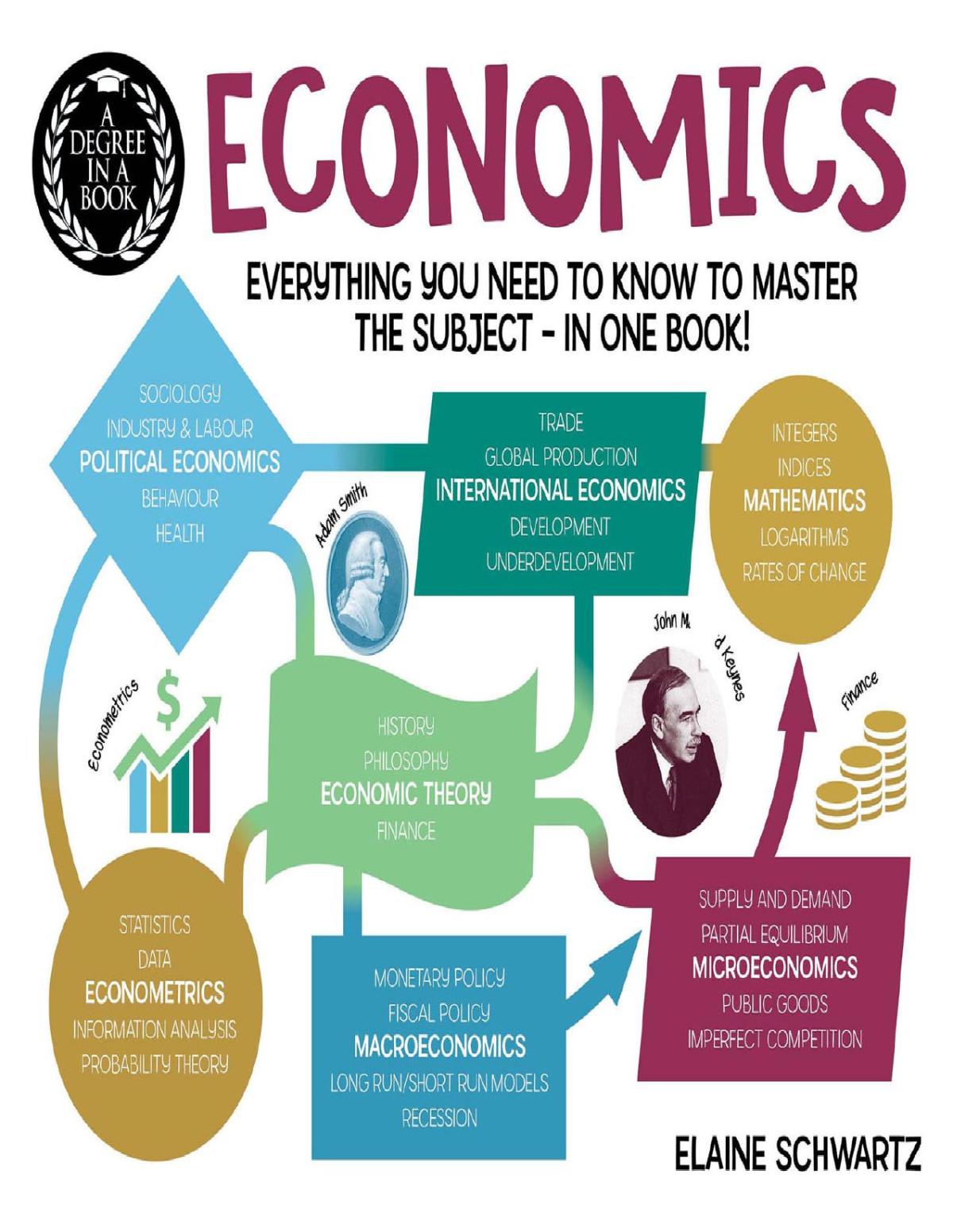

A Degree in a Book: Economics: Everything You Need to Know to Master the Subject – in One Book! Elaine Schwartz

https://ebookmass.com/product/a-degree-in-a-book-economics-everythingyou-need-to-know-to-master-the-subject-in-one-book-elaine-schwartz/

ebookmass.com

Multi-Layered Diplomacy in a Global State: The International Relations of California 1st ed. Edition Alison R. Holmes

https://ebookmass.com/product/multi-layered-diplomacy-in-a-globalstate-the-international-relations-of-california-1st-ed-edition-alisonr-holmes/ ebookmass.com

A Holy Baptism of Fire and Blood. The Bible and the American Civil War 1st Edition James P. Byrd

https://ebookmass.com/product/a-holy-baptism-of-fire-and-blood-thebible-and-the-american-civil-war-1st-edition-james-p-byrd/

ebookmass.com

Political Turmoil in a Tumultuous World 1st Edition David Carment

https://ebookmass.com/product/political-turmoil-in-a-tumultuousworld-1st-edition-david-carment/

ebookmass.com

Chemtrails existieren doch - Teil 3 - Chemische Kondensstreifen im 'Kampf' gegen den erlogenen Klimawandel Frank Hills

https://ebookmass.com/product/chemtrails-existieren-dochteil-3-chemische-kondensstreifen-im-kampf-gegen-den-erlogenenklimawandel-frank-hills/ ebookmass.com

Highland Gladiator Kathryn Le Veque

https://ebookmass.com/product/highland-gladiator-kathryn-le-veque-2/

ebookmass.com

ExpertDDx: Chest 2nd edition. Edition Brett W. Carter

https://ebookmass.com/product/expertddx-chest-2nd-edition-editionbrett-w-carter/

ebookmass.com

The Critique of Commodification: Contours of a PostCapitalist Society Christoph Hermann

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-critique-of-commodificationcontours-of-a-post-capitalist-society-christoph-hermann/

ebookmass.com

JAY M. FEINMAN

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

© Jay M. Feinman 2018

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Feinman, Jay M., author.

Title: Law 101 : everything you need to know about American law / Jay M. Feinman. Description: Fifth edition. | New York, NY : Oxford University Press, [2018] | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2017052995 | ISBN 9780190866327 (hardback) | ISBN 9780190866334 (updf) | ISBN 9780190866341 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: Law—United States—Popular works. | BISAC: LAW / General. | LAW / Administrative Law & Regulatory Practice. | LAW / Constitutional. Classification: LCC KF387 .F45 2018 | DDC 349.73—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017052995

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

Printed by Edwards Brothers Malloy, United States of America

To Leah and Bryan, Keith and Allie, and, more than ever, Carole

Preface xi

1 There Are No Secret Books: You Can Understand the Law 1

2 The Supreme Law of the Land: Constitutional Law 9

What is constitutional law? 9

Why do we need constitutional law? 14

How does the Supreme Court decide what the Constitution means? 18

Where does the Supreme Court get the authority to interpret the Constitution? 24

What powers does constitutional law give to the rest of the federal government? 30

What powers do the states have under constitutional law? 42

3 First Freedoms: Constitutional Rights 47

What rights does constitutional law protect? 47

What is due process? 49

Does constitutional law require that everyone be treated equally? 53

How does the Constitution protect freedom of speech? 60

How does the Constitution protect freedom of religion? 74

What other rights are protected by the Constitution? 81

4 Your Day in Court: The Litigation Process 95

What is civil procedure? 95

Why do we need civil litigation and civil procedure? 98

Where do court cases come from? 100

Where can a lawsuit be brought? 102

When can you make a federal case out of it? 105

If you can sue in different places, what law will apply in each place? 109

How does a lawsuit begin? 110

What can the defendant do to respond to a lawsuit? 112

What if there are more than two parties to a lawsuit? 115

What if there are many parties to a lawsuit? 118

How do the parties discover the facts about their case? 119

What else happens before the trial? 123

What happens at trial? 125

What evidence can be presented at trial? 128

What about the jury? 130

What happens after trial? 136

5 Hot Coffee and Crashing Cars: Tort Law 141

What is tort law? 142

Why do we need tort law? 144

Is it a tort when you hit someone? 149

Is it a tort when you injure someone by not being careful? 152

What does the law mean by reasonable care? 156

How does a plaintiff prove that a defendant has been negligent? 159

What if the victim is partly at fault for an accident? 162

If someone does not intend to injure someone else and acts with reasonable care, can he or she still be liable in tort? 164

When is a manufacturer liable for injuries caused by its products? 165

What damages can a plaintiff get in a tort case? 171

When are damages awarded to punish the defendant? 176

6 A Deal’s a Deal: Contract Law 179

What is contract law? 179

Why do we need contract law? 180

How do you make a contract? 185

Does a contract have to be in writing to be enforceable? 189

Can anyone make a contract? 191

Once two people make an agreement, is it always enforceable? 192

If a contract is unfair, can a court refuse to enforce it? 195

How does the law treat form contracts and online contracts? 197

Once you make a contract, can you ever get out of it? 202

What happens if one party’s performance depends on something happening and it doesn’t happen? 204

Will a court order someone to perform a contract? 207

How much does someone have to pay for not keeping a promise? 209

7 You Are What You Own: Property Law 213

What is property law? 213

Why do we need property law? 217

What kinds of property are there? 220

Who owns the Internet? 223

How can someone acquire property? 226

How is property purchased and sold? 229

How is property transferred on death? 234

What is a trust? 239

How do people own property collectively? 239

How else can ownership of property be shared? 243

What are the property rights of a landlord and a tenant? 246

When can the government take your property? 249

8 Crime Doesn’t Pay: Criminal Law 255

What is criminal law? 255

Why do we need criminal law? 259

What is a criminal act? 263

Does someone have to mean to commit a crime to be guilty? 266

When is self-defense justified? 270

When are the police justified in using force? 273

In what other circumstances is someone justified in committing a crime? 275

Why are criminals allowed to plead insanity as a defense? 278

What other defenses are available? 284

Can someone be convicted for almost committing a crime? 286

What is homicide? 291

Why is rape law so controversial? 296

9 Protecting the Innocent, Freeing the Guilty: Criminal Procedure 301

What is criminal procedure? 301

Why do we need criminal procedure? 303

What are the steps in the criminal process? 306

When can the police conduct a search and seizure? 309

What is the privilege against self-incrimination? 315

What happens if police violate a defendant’s rights? 319

What is plea bargaining? 322

Why do we have juries? 326

What is the adversary process? 330

How does sentencing work? 333

What about the death penalty? 337

Why does it seem that criminal appeals go on so long? 341

Conclusion 347

Index of Legal Cases 349

Index of Subjects 353

Preface

Law is everywhere. Check the news any day and you’ll hear about a notorious criminal trial, a massive lawsuit, or a new constitutional claim. And it all seems so complicated. Why are there legal technicalities that trip up the police and allow criminals to get off? Why does litigation take so long and cost so much? How do the courts figure out how the words of the Constitution apply to situations the framers never dreamed of?

Lawyers are trained to understand issues like these, and there are plenty of resources to help them. The library at my law school has more than a million volumes and innumerable online resources in which lawyers can find statutes, judicial opinions, and learned commentary on the law. This book is for everybody else. Law 101 is a basic explanation of the rules and principles that lawyers and judges use. The premise of the book is straightforward: It’s not easy to decide legal questions, but anyone can acquire a basic understanding of what the questions involve. Each of the substantive chapters of the book covers one of the basic subjects that every lawyer learns during the first year of law school: constitutional law, civil rights, civil procedure and the litigation process, torts, contracts, property, criminal law, and criminal procedure. In each chapter you will learn the fundamental principles that underlie the subject, acquire a legal vocabulary, and see how the rules are applied in ordinary and unusual situations. (If you want simple definitions of even more legal terms, consult this book’s companion volume, 1001 Legal Words You Need to Know.) The book not only tells you about the law— more importantly, it engages you in the process of lawmaking by asking you to think about the tough questions and troubling cases that lawyers and judges face. You will have some fun along the way as well, because the situations the law deals with are always interesting and sometimes amusing or outrageous.

After reading this book, when you hear about controversial legal issues you will have a better sense of the background and the complexity of the issues and you will be better able to make your own judgments about what the law should be. You also will be better prepared to think about the legal problems that you may encounter in everyday life, from owning a home to suing someone to asserting your constitutional rights. If you ever have considered going to law school, Law 101 will give you a taste of what it is like. And if you are a student, either in law school

or elsewhere, it will give you the big picture of basic legal subjects that otherwise can be hard to obtain.

Although I am a lawyer and law professor, writing and revising this book have been as much of an education for me as I hope it will be for its readers. I have had to rethink many subjects that are not my specialties, and I have freshly examined areas I have studied for years. I am very grateful to all of those who helped me in the process. Carl Bogus, Dennis Braithwaite, Ed Chase, Kim Ferzan, Beth Hillman, Greg Lastowka, Thomas LeBien, Earl Maltz, Stanislaw Pomorski, Mike Sepanic, Rick Singer, Allan Stein, and Bob Williams gave me excellent comments. Elizabeth Boyd, Sheryl Fay, Nicole Friant, Amy Newnam, and Beth Pascal provided helpful research assistance. Chris Carr and Bill Lutz gave early support. Rutgers Law School and its deans have provided an environment in which work of this kind could be done. Most of all, thanks to John Wright, who made it happen.

There Are No Secret Books

You Can Understand the Law

Americans are fascinated by the law. And why not? The law is important, intellectually challenging, and sometimes outrageous. Consider some cases that have made front-page news:

• Stella Liebeck, seventy-nine years old, bought a cup of coffee at the drive-through window of a McDonald’s in Albuquerque, New Mexico. As she placed the cup between her legs to remove the lid to add cream and sugar, she spilled the coffee, scalding herself. Liebeck’s injuries sent her to the hospital for seven days for burn treatment, including skin grafts, so she sued McDonald’s, alleging that the coffee was dangerously hot. A jury awarded her $160,000 to compensate her for her injuries and $2.7 million to punish McDonald’s, an amount the jury calculated was equal to two days of coffee sales for McDonald’s. (The trial judge later reduced the punitive damage award to $480,000.) Was this an outrageous example of a tort system run amok, or a fair judgment for an injured victim against a wrongdoer? See Chapter 5.

• James Obergefell and John Arthur met, fell in love, and established a decades-long committed relationship. After John was diagnosed with ALS, or Lou Gehrig’s disease, a debilitating, progressive illness with no cure, they wanted to marry before James died. They flew from their home in Ohio to Maryland, where same-sex marriage was legal, and were wed. After John died three months later, James could not be listed as the surviving spouse on John’s death certificate because Ohio did not recognize same-sex marriage. James sued, and the Supreme Court held that the Fourteenth Amendment required states to issue marriage licenses to same-sex couples and to recognize such

marriages performed in other states. How do the justices know what the Constitution means in cases like these? See Chapter 3.

• Ferguson, Missouri, police officer Darren Wilson approached Michael Brown, an African American teenager, following the robbery of a convenience store; a struggle took place between Brown and Wilson and then Brown fled. Witness accounts were in conflict about just what happened next, but in the end Wilson shot the unarmed Brown at least six times, killing him. A grand jury investigated and refused to indict Wilson for homicide. Brown’s death and the grand jury’s decision contributed to the spread of the Black Lives Matter movement. When can a police officer use deadly force in arresting a suspect? See Chapter 8.

Most of the law is not about important cases like the constitutional protection of same-sex marriage or dramatic cases like Michael Brown’s shooting. Law penetrates our everyday life in many ways. Critics charge that in recent years we have become plagued with “hyperlexis”—too much law and too many lawyers—but law has pervaded our society from the beginning. Even before the Pilgrims landed in Massachusetts they formulated the Mayflower Compact, a legal document that governed their settlement of the new world. In colonial times, legal regulation of the economy, public conduct, and social morality was at least as extensive as it is today. Common human failings such as fornication, drunkenness, and idleness were legally—and frequently—punished, and laws closely regulated economic affairs, prescribing the size of loaves of bread and the time and place at which goods could be sold. Ordinary litigation provided an occasion for public gathering, with great orations by the lawyers and much comment by the public. Today the law affects us individually when we rent apartments or own homes, marry, drive cars, borrow money, purchase goods, belong to organizations, go to school or work, and obtain health care and collectively when the government taxes, regulates the airwaves and cyberspace, polices crime, and controls pollution.

For all our endless fascination with the law, it is hard for most people to learn much about its substance. The law is so complex and voluminous that no one, not even the most knowledgeable lawyer, can understand it all. Moreover, lawyers and legal scholars have not gone out of their way to make the law accessible to the ordinary person. Just the opposite: Legal professionals, like the priests of some obscure religion, too often try to keep the law mysterious and inaccessible.

But everybody can learn something about the law. That is what Law 101 is for. It explains the basics of the law—the rules, principles, and arguments that lawyers and judges use. Not all the law is here; there is just too much law for anyone to learn more than a few pieces of it here and there. That’s one reason that most lawyers specialize, so that they can learn in depth the law of medical malpractice in New Jersey or federal tax law relating to corporations, for example. But all lawyers do know pretty much the same things when it comes to basic subjects and basic concepts, because they all go through a similar law school experience.

The public seems to be morbidly fascinated by law school as much as by law. Books and movies from The Paper Chase to Legally Blonde have fed the folklore of the first year of law school as an intellectually stimulating but grueling and dehumanizing experience. Because the first year of law school is the near-universal training ground for lawyers, this book focuses on the substance of what law students learn there as the core of knowledge that is useful and interesting to nonlawyers as well.

The first-year curriculum in nearly every American law school looks alike. A few topics are fundamental, and this book explores those topics. Constitutional law involves the structure of government (Chapter 2) and personal liberties protected from government action (Chapter 3). Civil procedure concerns the process of litigation (Chapter 4). Tort law concerns personal injuries (Chapter 5). Contract law is the law of private agreements (Chapter 6). Property law governs relationships among people with respect to the ownership of things (Chapter 7). Criminal law defines wrongful conduct for which the state can deprive a person of life or liberty (Chapter 8). Criminal procedure prescribes the process of criminal adjudication and the rights of defendants (Chapter 9).

Nearly every law school offers courses in constitutional law, contract law, and the rest, and the courses taught in different schools resemble each other to a considerable degree in the materials used and the topics covered. Schools in New Jersey, Iowa, and California all teach basic principles of national law, often using the same judicial opinions and statutes. If you attend law school after reading this book, you will find much of the first year will be familiar to you. Every course is taught by a different professor, however, and every professor has a different perspective. Some of those differences in perspective are trivial, but some are crucial. One professor may be a political liberal, another a conservative. One may favor economic analysis as a key to understanding the law, while another takes a natural law approach. Each of these differences in perspective, and the many others that occur, leads to a very different understanding

of what the law is. So while law students and lawyers all understand the same law in principle, they understand it in different ways.

This book has a perspective, too. It couldn’t be any other way. The perspective of this book is informed by much of the best scholarship about the law. Some of the elements of the perspective are widely accepted, and others are more controversial. The perspective can be summed up in a few insights about the law, as follows.

Law is not in the law books. Books are one of the first things that come to mind when we think about law: fat texts almost too heavy to lift; dust-covered, leather-bound tomes of precedents; law libraries filled with rows and rows of statutes and judicial opinions. While books tell us a lot about the law, they are not the law. Instead, law lives in conduct, not on the printed page; it exists in the interactions of judges, lawyers, and ordinary citizens.

Think, for example, about one of the laws we most commonly encounter: the speed limit. What is the legal speed limit on most interstate highways? Someone who looked only in the law books might think the answer is 65 mph, but we know better. If you drive at 65 mph on the New Jersey Turnpike, be prepared to have a truck bearing down on you, flashing its lights to get you to pull into the slow lane. The speed limit according to drivers’ conduct is considerably higher than 65. And legal officials act the same way. The police allow drivers a cushion and never give a speeding ticket to someone who is going 66. If they did, the judges would laugh them out of traffic court. As a practical matter, the court doesn’t want to waste its time with someone who violated the speed limit by 1 mph, and as a matter of law, the police radar may not be accurate enough to draw that fine a line anyway. So what is the law on how fast you can drive? Something different than the books say.

To understand the law, then, we have to examine events as they occur in the world. We can generalize from those events and create theories and concepts to inform our understanding of the law, but the touchstone is always the world and not the idea. One way this is done in law school is by focusing on individual fact situations that give rise to litigation and on the judicial opinions that resolve the situations, known as cases. Each of these cases starts out as a real-world event, such as Stella Liebeck’s suit against McDonald’s or the killing of Michael Brown by Officer Darren Wilson, and becomes the vehicle for thinking about many related events in a way that allows us to go back and forth between the particular fact situation and a general principle of law. This book follows that model and uses many interesting cases to explore legal principles.

Law is not secret. Along with the mistaken notion that the law resides in the books goes the equally mistaken idea that law is secret, or at least

inaccessible to the ordinary person. To understand and apply the law at the advanced, technical level that lawyers do requires professional knowledge, but to understand the basic substance of the law does not. Law reflects life. The principles and issues embodied in the law are not different from those that we experience in other aspects of our lives. Contract law, for example, is a commentary on the way people make, interpret, keep, and break their promises in commercial and noncommercial settings. Few nonlawyers can describe the objective theory of contract formation or the Statute of Frauds (you will be able to after you read Chapter 6), but they have thought a lot about contracts and promises. If you cross your fingers when you make a promise, does it mean that the promise doesn’t count? If you promise to take your children to the movies, are you off the hook if an important business meeting comes up in the meantime? What about if you just don’t feel like it? If your newly purchased television doesn’t work, can you return it to the store? And so on.

These are the kinds of issues that we all confront every day. The law provides a different forum for the discussion of these issues and the exploration of the principles, and the basic ideas involved are wholly accessible to the nonlawyer.

There are no simple answers. Law reflects life, and life is complicated. Therefore, legal problems defy simple solutions.

Life is complicated in two ways. First, things are often messy, so it is hard to define a legal issue and construct an appropriate solution. Think about the speed limit. If we formulate a clear rule, in this instance “driving faster than the speed limit is a crime,” we will inevitably end up with exceptions, such as “a parent rushing a desperately ill child to the hospital may exceed the speed limit.” If we formulate a fuzzy rule— “drive at a speed that is reasonable under the circumstances”—we will engender arguments in every case about how the rule should apply.

Second, life is complicated because we often are of two minds about an issue. We would like to have clear legal rules to ensure consistency, fairness, and predictability. But we want to make room for the equities of individual cases in which the application of a rule would produce an unfair result, in order to relieve a particular party of the hardship of the rule.

Politicians often would like us to think that there are simple answers to tough legal questions. Over the past few years we have become accustomed to sound-bite politics and simplistic ideologies that assert that all our problems can be solved by cutting down on frivolous litigation, getting tough on crime, making people responsible for their actions, or adhering to some other slogan. From the perspective used in this book, it’s just not so.

Law is a battleground of political conflict. The complex questions with which law deals and our conflicting responses to them are the stuff of political controversy. This is not politics in the Republican–Democratic, electoral sense, but a struggle over social resources and social values just the same. At stake in legal decisions are the most fundamental kinds of questions with which any society has to grapple: Who gets what? Who lives and who dies? What is right and what is wrong? Everyone can see this in major constitutional issues like the abortion controversy, but it applies to all other legal issues, too. Should fast-food chains be liable for obesity-related illnesses because they promote and sell super-sized portions of fattening foods? We have to see all legal decisions like this as political in a broad sense.

People make the law. Often, the law appears to be part of the natural order of things. The law and legal decisions can be seen as inevitable, based on immutable principles of justice, hardly the product of human action at all. Lawyers and judges speak as if the law itself were acting, free from their intervention: “The law requires that . . . ” or “The precedents determine a result. . . . ” Nonsense. Law is made by people, and “the law” or “the precedents” never control anything; we control them. All this view does is let a small group of people—the privileged, the politically powerful, and the legal professionals—control the legal system while they deny their responsibility for doing so. Whether the issue is abortion, manufacturers’ liability, or the enforceability of handshake agreements, all of us—not just the lawyers and judges—have to decide what we think is a fair and useful result.

This book strips away the mystery of the law to allow the nonlawyer to understand the rules of law and the principles and conflicts that are behind them. It doesn’t tell you how to be your own lawyer. You won’t learn how to file for divorce, sue in small claims court, or draft your own will. Other books convey that kind of advice; this one deals with issues that are more important, if less immediate. It explores the big issues that are fundamental to law, not the mechanics of particular transactions. Later, whether you use a how-to manual or go to a lawyer to deal with a legal matter, you will have a better sense of what is going on behind the rules and mechanics. And there is an important difference between this book and other law books, whether professional treatises for lawyers or how-to manuals on will drafting: This one is fun to read. The invented children’s author Lemony Snicket wrote, “Books about the law are notorious for being very long, very dull, and very difficult to read.” Not Law 101. Like the law itself, this book is full of puzzles, challenges, interesting tidbits, thought-provoking questions, and intellectual stimulation.

Each chapter is organized in question-and-answer format. The questions provide guideposts to the development of the chapter, and they make it possible to read selectively by dipping into particular topics of interest. At many points there are more questions than answers, and issues are left unresolved. Students of the law—and now you are one of them—experience this frequently and find it very frustrating. But that’s the way it has to be. The law doesn’t clearly answer some questions, and some issues are never finally settled. The courts cannot decide everything; figuring out the just solutions to hard problems is the right and duty of every informed person. After reading this book, you should be in a better position to participate in the process.

The Supreme Law of the Land

Constitutional Law

People who don’t know anything about civil procedure or property law can still recall the basic elements of constitutional law from their eighthgrade civics class: separation of powers; checks and balances; judicial review; due process and equal protection of law; freedom of speech, religion, and press. And if they can’t remember what they learned in the eighth grade, the news will remind them of the continuing significance of constitutional law. Is abortion constitutionally protected? How about same-sex marriage? Do corporations have free-speech rights?

Everything the government does is bounded by the Constitution. Constitutional law defines the relations between the president and Congress and between the federal government and the states, and it regulates the government’s ability to assess taxes, to build highways, to maintain and deploy the armed forces, and to print stamps. Moreover, every hot issue seems to become a constitutional question. Once it was the constitutionality of slavery or of laws establishing maximum hours and minimum wages for workers; now it is abortion, LGBT rights, and campaign financing. In the aftermath of the 2000 election, even who should be president became a constitutional issue, in the litigation resulting in the Supreme Court’s decision in Bush v. Gore. So constitutional law—how our government is organized and what it can and cannot do—is the place to begin our exploration of American law.

What Is Constitutional Law?

Constitutional law involves the interpretation and application of the U.S. Constitution and each state’s constitution (more on state constitutions shortly). Drafted in 1787, the U.S. Constitution contains fewer than 4,400 words, divided into seven short parts called articles. The Bill of Rights (the first ten amendments to the Constitution) was added in 1791,

and only seventeen more amendments have been added in the more than two centuries since. It wouldn’t take you long to do what few Americans do—read the whole Constitution, front to back.

It seems that constitutional law ought to be easy to understand. But despite the Constitution’s simplicity—or perhaps because of it—what the Constitution means and how it should apply are the most hotly debated topics of the law. And constitutional law is unique among all the bodies of law we will consider in this book, for four reasons.

First, other bodies of law work together. Property law creates rights in things like land and refrigerators, and contract law prescribes how to transfer those rights to another person. Tort law defines the right of an injured person to recover damages from a wrongdoer, and civil procedure establishes the process by which the victim can recover. But constitutional law has a different subject matter and a different status than the other fields of law. Constitutional law doesn’t address relations among individuals the way property, contract, and tort law do. Instead, it defines the structure and function of the government and the relationships between the government and individual citizens. It also defines the relative powers of the national government and the state governments and prohibits the government from taking certain actions, such as those that infringe on freedom of religion. In defining and limiting government powers, constitutional law is superior to every other body of law. The Constitution proclaims itself to be “the supreme Law of the Land.” Any state or federal law on any topic—contracts, criminal punishment, campaign contributions, or public schools—that conflicts with the Constitution is invalid.

Second, other bodies of law are based on a mix of statutes and judicial decisions that provide a wide range of sources for rules, principles, and arguments. Contract law, for example, began as a common law subject determined by judges and has been overlaid by legislation. To decide a contracts case, a court can look to a rich variety of sources, from old English precedents to modern state statutes. Constitutional law is different. All constitutional decisions ultimately refer to a single, narrow source: the text of the Constitution with its amendments.

The necessary reference to a single text makes constitutional law so challenging because of the infinitely broad range of situations that the text must cover. When the constitutional text addresses a narrow issue and does so specifically, we have little problem in figuring out how to apply the text; more often, the text is vague and the cases that it covers are much more diverse, so we have to decide what the text means and what result follows from it in a particular case. Sometimes, by universal agreement, the words mean something other than what they appear to

mean. The First Amendment states that “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof,” but even the most ardent strict constructionist understands that the amendment also applies to the president and the courts. Other times the words demand extensive interpretation. Does the constitutional command that no state may “deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws” mean that a state university cannot give a preference in admissions to African American students in order to diversify its student body?

Third, constitutional law, more obviously than other areas of law, raises fundamental political issues and value choices. One of the themes of this book is that every body of law and every legal decision implicates important values; tort law, for example, forces us to make important choices about to what extent people must take account of the harm they may cause to other people. But in constitutional law, the value questions are more readily apparent and therefore are more controversial. If all law is politics to some extent, constitutional law is more explicitly political than other bodies of law. There are very few simple or noncontroversial issues in interpreting and applying the Constitution.

Fourth, in other areas of law the processes of making and applying law seem obvious and appropriate. Legislatures and courts formulate principles of law, and courts apply those principles in deciding individual cases. In constitutional law the decision process also is clear, but whether it is appropriate is much more contested. In other areas of law the power of the courts is taken for granted, even if the correctness of the results they reach may not be. In constitutional law, by contrast, the central issues are why judges have the power to be the final arbiters of constitutional law and what theories of constitutional interpretation they should use in interpreting and applying the Constitution.

When the constitutional text requires interpreting, the courts do so, especially at the federal level. If necessary, cases are taken to the top, to be heard by the nine justices of the U.S. Supreme Court. But the Supreme Court justices are appointed, not elected, and once appointed they serve for life, without ever being subject to review again. If constitutional law involves fundamental political issues, why can those issues be decided for a democratic society by such an undemocratic institution? Moreover, the more overtly political institutions of government such as Congress resolve political issues by consulting constituents, being lobbied by interest groups, looking at opinion polls, and openly debating the pros and cons. How does the Supreme Court decide hot political issues when it apparently is insulated from the political process?