Series Editor’s INTRODUCTION

Oxford Keynotes reimagines the canons of Western music for the twenty-first century. With each of its volumes dedicated to a single composition or album, the series provides an informed, critical, and provocative companion to music as artwork and experience. Books in the series explore how works of music have engaged listeners, performers, artists, and others through history and in the present. They illuminate the roles of musicians and musics in shaping Western cultures and societies, and they seek to spark discussion of ongoing transitions in contemporary musical landscapes. Each approaches its key work in a unique way, tailored to the distinct opportunities that the work presents. Targeted at performers, curious listeners, and advanced undergraduates, volumes in the series are written by expert and engaging voices in their fields and will therefore be of significant interest to scholars and critics as well.

In selecting titles for the series, Oxford Keynotes balances two ways of defining the canons of Western music: as lists of works that critics and scholars deem to have

articulated key moments in the history of the art and as lists of works that make up the bulk of what consumers listen to, purchase, and perform today. Often, the two lists intersect, but the overlap is imperfect. While not neglecting the first, Oxford Keynotes gives considerable weight to the second. It confronts the musicological canon with the living repertoire of performance and recording in classical, popular, jazz, and other idioms. And it seeks to expand that living repertoire through the latest musicological research.

Kevin Bartig

Michigan State UniversityI always just wanted to make things that other people could understand. That’s my only reason to be here.

Laurie Anderson1

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Thank you to Laurie Anderson for her communication and to Lysee Webb, who helped coordinate it. I’m grateful for the discussions I had with Perry Hoberman, Roma Baran, Bob Bielecki, B. George, Stephen Paul Miller, Margaret Fisher, Jon Kutner, and the Oakland Symphony. Robert Coe, Bob Hughes, and Charles Amirkhanian went above and beyond in their assistance; this would be a lesser book without them.

I owe a debt to the curators, archivists, museum professionals, and librarians who helped with my research: Edmund Cardoni, Timothy Conway Murray, Nicole Marchesseau, Andy Leach, Shannon Erb, Gretchen Unico, Jennie Thomas, Laura Maidens, Denise Markonish, Laura Schieb, Carol Berg, and Nick Ferreira. My work was improved by online resources by Jim Davies and Mnemosyne. Simon Morrison, Jason Hanley, and Mandy Smith offered wisdom and assistance with my fellowship from the American Musicological Society and the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in May 2019. Fond remembrance is also due to the late Bob Judd, who guided me through that process

and who was always encouraging. Susan McClary graced my lecture at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame with opening remarks for which I am grateful. Insightful, alarming, and entertaining, this late-1980s memory of hers was a particularly clear indicator of Big Science’s power:

I was asked to come and give a talk at a country club in front of a big interdisciplinary audience. At the time I was working on Laurie Anderson, and I thought, “Oh, I’ll talk about ‘Big Science.’ ” And so I talked a little bit and then I started playing the recording. Now, there were a lot of scientists in the room, and they got so agitated that they rushed the stage, and the police had to be called in. My husband actually thought he was going to have to take a bullet that night. It was one of the scariest things he ever saw.2

Thanks are also due to those who hosted my Big Science lectures: Amanda Eubanks Winkler and Theo Cateforis (Syracuse), Judith Peraino and Roger Moseley (Cornell), Doug McLaren (Cornell Cinema), and Peter Burkholder, Halina Goldberg, Phil Ford, and Giovanni Zanovello (Indiana University). Beyond these engagements, I delivered related research at the Conference on Interdisciplinary Musicology (2005), the FSU Music Theory Forum (2008), the Audio Engineering Society National Meeting (2013), the MoPop Pop Con (2018), the Art of Record Production (2019), and the Ithaca Music Forum (2019).

I received institutional, professional, social, and moral support from friends at Ithaca College including Karl Paulnack, Tim Johnson, Debbie Rifkin, Peter Silberman, Craig Cummings, David Pacun, Crystal Peebles, Elizabeth

Medina-Gray, Kris Shanton, and Sarah Shank. I had tremendous help and inspiration from Sara Haefeli. Certainly many more here have helped me too.

I’m grateful for deep conversations with my students and with Sasha Geffen, Alex Blue V, Des Harmon, Jim Anderson, Trevor Pinch, Benjamin Piekut, Chris O’Leary, Evelyn McDonnell, Maria Buszek, Sasha Frere-Jones, Chloe McLaren, Sydney Kovar, Ellen Jackson, Sarah Hennies, Jess Zimmerman, Aaron Fuleki, Janet Hanseth, Woody Chichester, Jacek Kozlowski, Erika Moore Bertelsen, Bob Proehl, Tiffany Naiman, Sarah Noe, Stephan Pennington, K. E. Goldschmitt, Albin Zak, Lori Burns, Eric Weisbard, Matthew Baumer, Lindsey O’Brien, and Maria Murphy. My sisters Karen and Robyn, along with Tico Wolff, Chris Boone, Ian Struckhoff, and Charles Dodge, deepened my early love of this album.

Tremendous thanks go to those who read and provided feedback on this work, including several anonymous reviewers, Elizabeth Sandifer, and Vic Szabo. In this capacity, Robin James and (again) Phil Ford offered profound insight. My early scholarship on Laurie Anderson was guided by Mathew Rosenblum, Eric Moe, Andrew Weintraub, and Peter Havholm. Mary Lewis, you are missed. Kevin Karnes and Suzanne Ryan believed in this book enough to make me write it. Norm Hirschy, Mary Horn, Kevin Bartig, Sean Decker, and Victoria Dixon were also a great help. Sindhuja Vijayabaskaran, project manager at Newgen KnowledgeWorks Private Limited, ably assisted with copy editing and layout.

Across several intermittent years of typing, my lap was warmed by Amelia, Pie May, Cabot, Princess Peppercorn, Braeburn, and Thistle. Above all, thank you to Meredith Collins, for her insight, inspiration, style, magic, and love. The cover design for this book was her idea too.

CHAPTER 1

FINDING THE NOW IN BIG SCIENCE

THE TIME

Laurie Anderson’s 1982 debut LP, Big Science, opens as if her voice has been waiting for us to show up: “Good evening. This is your Captain.” In welcoming listeners to board the plane, to hear the album, and indeed to behold her career, she offers coolheaded assurance. This space is well prepared. You are in good hands. On the album’s cover, she wears a suit and tie; everything is professional. And that’s when she announces the plane is about to crash.

Anderson’s iconic productions are hi-tech and seemingly dispassionate in their delivery. Vignettes are phrased optimally, their timing and inflection calculated. But deeper still, across hundreds of interviews, whole paragraphs recur verbatim. It can seem as if her stories were always already

Laurie Anderson’s Big Science. S. Alexander Reed, Oxford University Press. © Oxford University Press 2022. DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780190926014.003.0001

there, the opening of Big Science being just one example. Even when they concern the future, their creation is in past tense.

In fairness, I think we all do this. Our stories and catchphrases become word-for-word routines. Gradually drifting from the real moments they memorialize, our stories settle. We perfect and package them like products to be circulated through our social and sentimental economies, where content seems to matter less than flow.

Anderson herself takes up this concern in her 2015 film Heart of a Dog. Having told a nonchalant anecdote all her life about being hospitalized at age twelve with a broken back, she one day “remembered the missing part”: the other children in the hospital, mostly with severe burns. “It was the way the ward sounded at night. It was the sounds of all the children crying and screaming. It was the sounds that children make when they’re dying.”1 She reflects, “I had forgotten what it was really like. And I had gotten caught up into the story about it. And so I realized that repetition does that with stories. And your identity does that with your own story too. The more you tell it, the more you forget it.”2 (Place a bookmark in the notion that stories outsource or externalize identity. This idea will come back at the book’s end in useful ways.)

“This is the time, and this is the record of the time,” Anderson repeats on the album’s opening track. A twentyfirst-century description of Big Science can shine light on the individual and cultural ways that we experience moments, remember them, and overwrite our experience with memory. For her part, Anderson authorized RoseLee Goldberg’s 2000 biography, wrote a career retrospective in

1993 (Stories from the Nerve Bible), wrote another in 2018 (All the Things I Lost in the Flood), and assembled multiple anniversary editions of Big Science. She quips, “I don’t miss the 80’s. I don’t miss anything right now. I have zero time for nostalgia.”3 Because Anderson has said about her early career most of what she is going to, this book is a thirdparty remaking of memory, imperfect and sometimes arbitrary, in which the record of the time offers up a reimagining of the time: the time of New York and America at the turn of the 1980s, the time of Anderson’s artistic self-making, the time you first heard her music, all those times it resonated later.

This book makes room for a now in songs that can seem always to have already arrived. Doing this means revealing moments that collectively triangulate a present-tense experience of memory making. Foremost, I’m interested in the circa 1980 creation of these songs: “now” in the sense of chronos, or historical sequence. How did their concept, text, and music develop, and in dialogue with what realworld artifacts and events? These works’ histories will indicate and exemplify the genesis of Anderson’s remarkable artistic and musical voice. (Accordingly, I’ll sometimes discuss her art from before and beyond Big Science; readers wanting texts and timelines of her career can find them in the sources I mentioned in the last paragraph.) Second, I also describe what it’s like to inhabit a private listening encounter, marking time not by dates and eras but from second to second: “now” in the sense of kairos, or experiential action. Third, I ask without nostalgia how Big Science resonates now in the twenty-first century, acknowledging in the book’s final chapter what some have heard as an

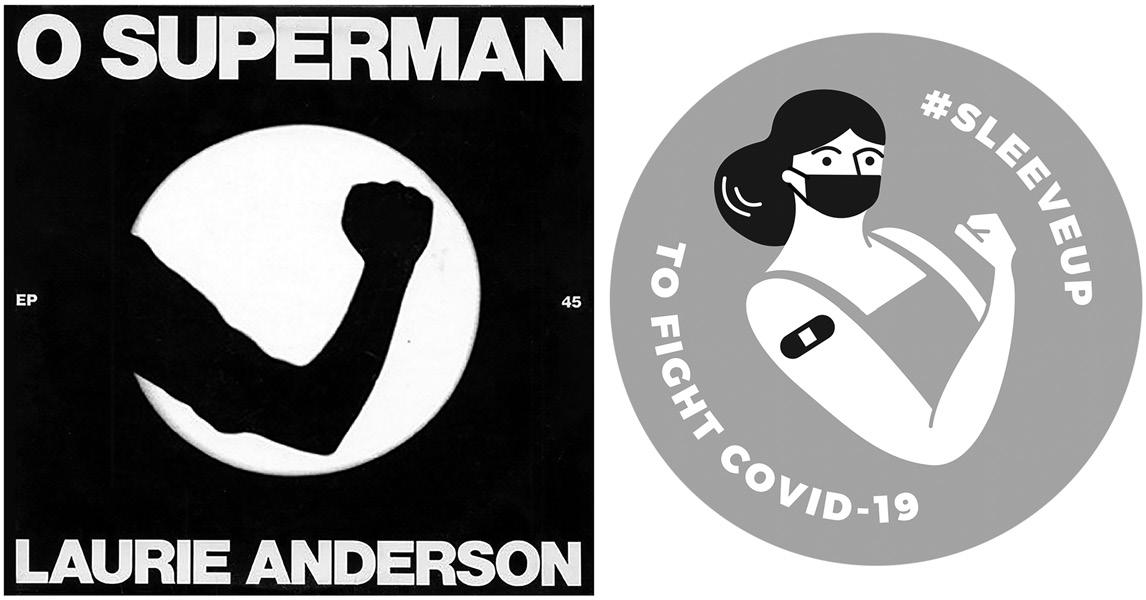

eerie prescience in the record. I write this in the midst of the COVID-19 shutdowns, when we rely on masks, when even intimate communication is mediated by technology, presaged by the phone calls and epistles in “O Superman,” “Example #22,” and “Let X = X” just as surely as “Here come the planes” portended 9/11. Vaccination stickers issued in 2021 by the Centers for Disease Control likewise recall Big Science in their nod to Rosie the Riveter (see figure 1.1).

Collectively, these approaches play the album in the present tense. This matters because mindful presence is both a topic and a strategy in Anderson’s music; its meanings lie in its doing. When we walk beside these songs and not against their grain, describing more than intercepting them, we hear how parts make up wholes. This book advances a hearing of Big Science invested in such experience (“justthisness”), yet situated within the national and the global.

Figure 1.1 Cover art for the “O Superman” single and a 2021 Centers for Disease Control COVID-19 vaccination sticker

THE RECORD OF THE TIME

Born to an affluent and large Chicago family, Laurie Anderson came to Manhattan for college in 1966, and throughout the 1970s, she established herself in the New York art scene as a sculptor, illustrator, photographer, storyteller, and critic. Some of her earliest work was intimate and self-effacing, inspired by her mentor Vito Acconci’s public auto-flagellation. Within a few years, though, she was seeking different self-presentation. In 1977, she told Fluxus artist Dick Higgins:

I used to use myself as subject matter pretty much—personal anecdotes, things that had happened to me.

Then I found that I ran out of them, and the second thing was I found I had two pasts, one was what happened and the second was what I had said about what happened.

I’m sure you’ve had that experience, of not being able to tell the difference.4

To this effect, some critics (all of them men) have, with apparent spite, singled out Anderson for blurring the line between history and narrative. Avant-garde chronicler Richard Kostelanetz dismisses her as “briefly popular in the early ’80s” and digs in: “Anderson’s work fails to meet the claims made for it, whether as visual art, music, writing, or performance. . . . It follows that Anderson herself fakes.”5 He then spends six lines excoriating her for such sins as misspelling Oskar Schlemmer’s name. Whatever. In the second half of the 1970s, Anderson began focusing on language, sound, and technology—spurred by a few important meetings with musicians, writers, and engineers

including Perry Hoberman, Bob Bielecki, John Giorno, Philip Glass, and beat author William S. Burroughs. Across a variety of media, small new works came fast, and so her project became one of organizing, juxtaposing, and optimizing them. Her audience was mostly fellow SoHo artists, but factual talk of her eventual stardom was in the air. Reviewing a 1970s concert, composer Tom Johnson writes, “Some were speculating that, with the help of a good record producer, she would emerge as the ’80s’ answer to Patti Smith.”6

In Anderson’s work, meanings pile up and commingle; it constitutes an “epic of concatenation,” writes media scholar Bart Testa.7 Concatenation applies to her early creative method, too. Particularly in the late 1970s, she was keen never to repeat a program in full, but the phrases, stories, and melodies of one dismantled cycle were fair game for the next. Across a dizzying number of commissions, grant projects, and exhibits, she regularly presented in-progress pieces and not-quite-sequels, hashing out variations on themes. “All of the pieces, in some way or another,” she said in 1979, “have a diagrammatic connection to each other.”8

Her goal wasn’t exactly the creation of a fugue-like corpus. In those pre-stardom days, she couldn’t rely on audiences’ knowing her catalog (and in fact she may have presupposed their unfamiliarity). Larger agglomerations overlapped, such as her For Instants series, the Jukebox exhibit at the Holly Solomon Gallery, and Americans on the Move. But the 1982 publication of Big Science, the 1983 performance of United States I–IV, and the 1984 release of United States Live effectively finalized this decade-long accumulation. “I’ve never done anything that I’ve considered

finished. So to have this on a record, not continually changing disturbs me,” she confessed.9

Here’s how she became a star. In April 1981, Anderson pressed a single of one the many songs from United States Part II as a proof of concept. With producer Roma Baran, she’d recorded it in her apartment hallway. Anderson and her former production manager B. George had gotten a small NEA grant to help manufacture the record; George released it on his microlabel One Ten Records. Anderson threw a release party for “O Superman” at the Kitchen (59 Wooster Street) on April 28, where she DJed a set that juxtaposed Dolly Parton, the BaBenzélé Pygmies, Vito Acconci, csárdás polka, Freddy Fender’s “How Much Is That Doggie in the Window?” in Spanish, African drumming, and the Beach Boys’ “Surfin’ USA.”

Outside of Manhattan, the single was no hit, initially selling few of its five thousand first-run copies, but American success was pretty much secondary to the plan. George recalls, “I had suggested that we needed to do a recording because I had the ability to play it on the radio in Britain, and that was really important.”10 In 1980, he’d published Volume, a wide-angled discography of punk, avant-garde, and new wave music, which had become a transatlantic Bible among collectors, DJs, and A&R staff. This earned him quick friendships with punk distributor Rough Trade and BBC1 tastemaker John Peel.

On or around August 25, 1981, George appeared on Peel’s late-night show in a guest role that allowed him (unlike Peel himself) to spin songs that hadn’t been greenlit by higherups. “I started doing an occasional show of bringing over six or so things that I thought [Peel’s] audience would like,” George recounts. “I think he heard it the first time live that

evening.”11 Fellow jockeys Simon Bates, Dave Lee Travis, and Richard Skinner immediately picked up on the record, giving it daytime airplay. “It went to breakfast radio, which means that every mom in England knew the song,” says George. “When I took a cab later that night, the cabbie said, ‘Oh, you’re the guy on the radio!’ and he started singing ‘O Superman’: ‘AH-AH-AH-AH.’ ”12

As August drew to a close, UK demand for the single grew high. Only five hundred copies had shipped over the Atlantic, but distributors were requesting tens of thousands. Rough Trade Records was keen to sign Anderson, and even began printing labels for the single in anticipation of a deal, but instead (with help from Baran), she called Karin Berg, a Warner Brothers A&R scout who’d been lurking at her shows. Berg, who’d signed Dire Straits, Television, Devo, and the B-52s, negotiated swiftly with Warner Brothers’ head of A&R Bob Regehr and with its London office for a massive eight-LP deal. Anderson herself was reluctant to play the pop game but took it on as a grand experiment. (That’s the official story, at least; since early 1979, though, she’d been making public announcements of a forthcoming album.)13 At the time, Regehr said of her music, “I like the wit of it. She’s very musical. Most performance artists and minimalists, which is a category she falls into, aren’t musical . . . the last time I felt this way was the Sex Pistols.”14

Warner Brothers quickly picked up the rights to “O Superman,” and by early October, it had gone top 20 in sixteen countries, taking the number two slot in the United Kingdom’s weirdest-ever top 5:

1. “It’s My Party,” Dave Stewart with Barbara Gaskin 2. “O Superman,” Laurie Anderson

3. “ The Birdie Song (Birdie Dance),” Tweets

4. “ Thunder in the Mountains,” Toyah

5. “Happy Birthday,” Altered Images

With the large Warner Brothers advance, she renovated her apartment into a recording studio and chose nine songs out of the seventy-eig ht constituting United States I–IV from which to make something like a pop album. Big Science was the result. Vitally, this book is concerned with the album as a functional unit and not some imperfect or incomplete slice of the “proper” experience. Big Science is, after all, how much of the world came to know Anderson.

The album sold well, almost going gold in America. More interesting is this: Anderson may have toiled for fifteen years in SoHo galleries and on the pages of Artforum, achieving cult status in that world, but to her new audience, she emerged from nowhere, fully formed like Athena. Seemingly overnight, she was an event, the first (perhaps the only) superstar of the multimedia avant-garde. As reviewer Rob le Frenais wrote, “the world knows what a performance artist is now.”15

WHAT IS BEHIND THAT CURTAIN?

Now that I’ve pointed toward the topic and scope of this book, allow me a word about its methods. The sensational early-1980s rise of Anderson’s star caused interpretive ripples in the way people wrote about her art. Years later, she’d recall:

I felt that my work was never actually described. I like to think I’ve gotten over that, but I do remember resenting being jammed into someone’s abstract essay on language. Or else the writing focused on the performance itself and analyzed the delivery— “cyberpunk,” “Jack Benny,” “midwestern Madonna”—or focused on the spiked hair or the shiny black jacket, as if I were someone who wandered onstage at the last minute to intone monologues that had appeared out of nowhere. . . . I never felt that art writers had the slightest idea what I was trying to do.16

It’s easy to grasp Anderson’s frustration with those who reframed her work, conscripted it to their academic agendas, caricatured it, poked at her, and careened otherwise between the intrusive and the irrelevant. In many ways, her attitude echoes the 1964 essay “Against Interpretation” by Susan Sontag, whom she’d later befriend. “The function of criticism,” Sontag writes of art, should be to show “that it is what it is, rather than to show what it means.”17 She calls for “a descriptive, rather than prescriptive, vocabulary,” hence Anderson’s wish that her work be “actually described.”18

As Anderson’s spiritual mentor Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche writes, “To the ear, sound is always just sound, nothing more. Like and dislike are shaped by the interpretive mind that remembers, adds, modifies, and spins: The interpretive mind creates entire fictions around just sound, just sight.”19 Sontag goes a step further: “The modern style of interpretation” doesn’t merely invent fictions, but “it excavates, destroys; it digs ‘behind’ the text, to find a sub-text which is the true one,” in favor of which critics too often discard the lived experience (the “erotics”) of art.20

Musicology has engaged extensively with Sontag’s arguments, and it’s not my goal here to evaluate or advance

that conversation.21 But I do want to recognize that Sontag’s words read like a creative blueprint for Big Science: “Ideally, it is possible to elude the interpreters in another way, by making works of art whose surface is so unified and clean, whose momentum is so rapid, whose address is so direct that the work can be . . . just what it is.”22 And so the album brandishes anti-interpretive defenses. Its professionalist sheen downplays markers of genre, gender, time, and place (even as that sheen is itself a prerogative of white intellectual culture). In Anderson’s text, we are undistracted by narrative, because characters and settings dissolve into one another. Real-world names and cities might feature in her other works, but not here, and so politics are submerged. Harmony is so limited and neutral that the album’s tonality seems a landscape of simple polygons. The meaning of words follows their function; “the sun is shining slowly” becomes a viable pop lyric. By setting the record’s scope so wide, seemingly the territory of Western modernity, her topic becomes the infinitude of lenses through which we can peer, preempting the value of any single interpretation— and arguably of interpretation itself. Accordingly, media scholar Douglas Kellner assesses, “Anderson’s images resist interpretation. Her art is an erotics of surfaces and the play of light, sound, movement, word, and performance.”23

Some of the first writing devoted to Anderson’s music (and still some of the best) comes from Susan McClary’s influential 1991 book Feminine Endings. “If her music resists analysis as we practice it in the academy,” she says, it’s “because her premises are different.”24 And so to see through the glossy surface of the LP down into its prismatic depth, we might refocus our listening in sympathy with those

different premises. McClary’s plural here draws our attention to the album’s uncontainable modeling of now at a scale of one to one. Notice the world, Big Science says, notice all of it.

No single key unlocks Anderson’s work, and no single meaning lurks encoded—as if one history or perspective could tidily hold such multitudes or negate the insight of all others. Just as Anderson mixes media in her art, I mix approaches to listening, leaning on urban history, experimental literature, phenomenology, and other perspectives outside my ostensible field of music theory. Analyze if we must, but without interpretive dogma and without mistaking map for territory. Nor, in what follows, do I defer to the internal features of Big Science as if any feature is merely internal, as if we hear any music disconnected from the world of style, convention, embodiment, and politics. But sometimes musical terminology can help explain what a song is doing as it moves along. Furthermore, I don’t hunt down and scrutinize the events of Anderson’s life in hopes of connecting a prurient moment to a key lyric—as if she herself were the text of Big Science. But I also take seriously her recollection in Heart of a Dog of the sawedin-half house sculptures by her friend Gordon Matta-Clark and her excoriation of the postmodernists who analyzed them but failed to connect them to the suicide of MattaClark’s twin brother, Sebastian. Anderson’s call isn’t to psychoanalyze but to acknowledge when biographical realities stare us in the face. Accordingly, I take as meaningful those moments when she writes and speaks of herself, while duly recognizing the circular ways that Big Science marks an ongoing negotiation of privacy amid a culture that demands

that women’s lives be public property. Finally, I resist documenting my own free association with this album—as if you would care. But I tune in to the intuitions I experience in its presence. If I hear something as meaningful, you might hear it too, and we might productively trace that insight— to our bodies, our culture, the sound, Anderson’s agency, or the prior world channeled into music.

I’m carefully agnostic, because academics get uniquely excited about theorizing Anderson’s work. Apparently speaking “our” language, she sparks questions that can seem more the stuff of philosophy than of pop. Anderson has published scholarly criticism and studied the philosophy of Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Mark Fisher, Jacques Derrida, and Walter Benjamin. She knows the musicology, urban studies, artificial intelligence research, and queer theory through which professors process her output. In an online chat, a fan asks, “Would you object to somebody writing a Ph.D. dissertation analyzing your work?” Acknowledging the many theses already written, Anderson (logged on as “Laurie 212”) replies, “I’ve got a collection of them and they’re pretty zippy reading.”25

Despite her awareness, Anderson rarely intellectualizes. She works through story, aphorism, and example— showing-not-telling or, more often, doing-not-telling. An essayist wary of technology, for instance, might cite political theorist Paul Virilio: “When you invent the plane you also invent the plane crash.”26 But Anderson spins your head in weirder 3D by saying, “I think we should put some mountains here. Otherwise, what are the characters going to fall off of?” Anderson does Virilio’s philosophy by staging

a business-as-usual air disaster—“Please extinguish all cigarettes”—in which the crash is the business.

All this matters because I’m writing primarily for the album’s fans, often overlooked in favor of cultural analysts and techno-utopians. This happens both because Anderson emerged from New York City’s artistic caste and because the literati were mostly the ones whose reactions to her work were preserved and reproduced. Their discussions inform this book, but let’s be canny about the self-serving ways intellectuals felt vindicated by Anderson’s popular rise, as if to say, “Here at last on the pop stage is one of our own, demanding our critical arsenal in all its shiny ferocity!” This hungry attitude pervades a decade of scholarship on her work and overlooks her impish rejection of standard academics: Anderson’s early monologues are rife with her own pranks against the stuffiness of teaching and critical writing. Unmoved by credential, she pushes against the ravenous philosophers. True, this book is secondarily written for my fellow musicologists, mostly in offering archival findings and in humble hopes of collating discussion around Anderson’s music and meanings. But to be clear, academia always stood to gain more from an affiliation than Anderson herself did.

Besides, she learned early on that crowds unschooled in her methods react with greater immediacy. Street and community performances in the early 1970s put her face to face with delighted and bewildered viewers. She witnessed her work’s mass appeal in February 1978 at a museum-sponsored show in Houston. “The museum was designed for people who were doing huge sculpture, not performance. There weren’t even chairs. So the event got

rescheduled in a country and western bar (the Texas Opry House),” she told a newspaper. “That changed my life, that particular event. Because, you know, the regulars came early to get a place at the bar, and then the art crowd comes in, fashionably late and all in black. At some point I realized that the regulars understood perfectly what I was doing. Wait! I thought, these people get it.”27 So where possible, this book privileges the immediacy of fan-level interaction with Anderson’s art and music, and if locating a here and now means less airtime for abstraction, then so be it.

In a few cases, though, an excursion into the conceptual will illuminate the conversations that have surrounded Big Science and help us understand its relevance today. Such is the case with chapters 2 and 8, which unpack bigness. Chapters 3 through 6 take up specifically musical concerns—the songs’ individual histories and features, as well as issues of genre. Chapter 7 addresses the structural and historical ways Anderson’s work navigates sexuality and gender.

Now, onward to the plural paths through these songs’ plurality.