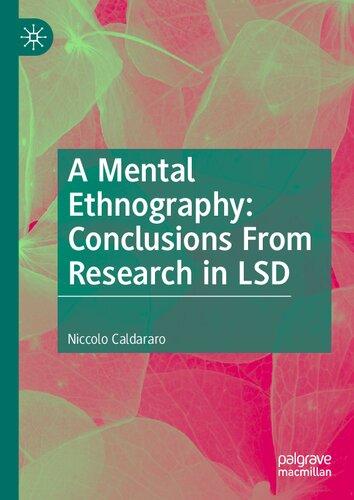

Laughter and Power in the Twelfth Century

PETER J. A. JONES

1

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP, United Kingdom

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries

© Peter J. A. Jones 2019

The moral rights of the author have been asserted First Edition published in 2019

Impression: 1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available

Library of Congress Control Number: 2019937241

ISBN 978–0–19–884354–2

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780198843542.001.0001

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. Oxford disclaims any responsibility for the materials contained in any third party website referenced in this work.

For Kevyn Rhys Jones (1953–2015) Rex ridens

Acknowledgments

While writing this book I had to move around a lot, and I often thought about quitting the project or giving up on the Middle Ages altogether. But the encouragement, support, and love of many people kept bringing me back.

First and foremost, I would like to thank Brigitte Bedos-Rezak at New York University. It would be impossible to imagine a better PhD advisor than Brigitte, whose guidance, patience, and care allowed me to develop a project that I was ready to give my heart to. Brigitte cannot take responsibility for any of my mistakes — those are all my own fault. But without her inspiration and support none of this research would have been possible.

In New York, I was also very lucky to receive guidance from Maryanne Kowaleski at Fordham University. Her introduction to resources, her good advice, and her writing coaching were extremely valuable in getting this project started. It was also a privilege to study at the IFA under Jonathan Alexander, whose suggestions were crucial in the early stages of my research. Both Michael Stoller and Fiona Griffiths offered me help at points when I had almost lost the thread of what I was doing, as did Kostis Smyrlis at NYU. Jay Diehl, Jessica Sechrist, Youn Jong Lee, Mike Peixoto, and James Robertson were all supportive as my research began. Most especially, I would like to thank William Jordan at Princeton, who took a great deal of time coaching me through some of the essentials of twelfth-century politics. He has offered feedback on this work at many points throughout the writing process, and I am very grateful for his continuing support and kindness.

In London, I received advice in the initial stages of my writing from Miles Taylor, Jonathan Waterlow, John Gillingham, Michael Clanchy, and Suzanne Reynolds. John Arnold provided me with feedback on an early draft of one of the chapters of this book, and I want to thank him and Tom Johnson for taking time to get me oriented in the London medievalist community. Gary Slapper was a wonderful host while I was a fellow at NYU London in 2013, and his enthusiasm for the project was uplifting. In Norwich, Nick Vincent was generous in helping me get started, and I want to thank him especially for providing me with many materials that I would otherwise never have found.

In Toronto, I was very lucky to develop much of this research as a fellow at the Jackman Humanities Institute from 2014 to 2016. Bob Gibbs and Kim Yates created an ideal work environment, and provided care and support as I encountered a number of difficulties. Many of the ideas for this book grew in the institute’s seminars on “Humour, Play, and Games,” and I am especially grateful to Matt Cohn, Maggie Hennefeld, Katie Price, Simon Dickie, Jeanne Mathieu-Lessard, and

Oisin Keohane for helping me to see new sides of the topic. I am also thankful to Isabelle Cochelin and Michael Meyerson, from the university’s history department, for their advice and mentorship.

In Providence, I am thankful for the support of Suzanne Stewart Steinberg and Donna Goodnow, who helped me while I was a visiting scholar at the Pembroke Center at Brown University from 2016 to 2017. Within the university’s history department, I would also like to thank Amy Remensnyder for taking time to discuss my research. I am especially grateful, also, for the kind help of Pinar Kemerli and Simon Gilhooley.

In Dublin, I would like to thank Kevin Whelan, Eimear Clowry Delaney, and everyone at the Notre Dame Keough-Naughton Center for letting me take part in their wonderful yearly seminars. Further afield in Tullow, my thanks to Margaret Mulhall for giving me the fortification to see the project through.

In Tyumen, I am indebted to Andrey Shcherbenok and all of the staff and scholars at the School of Advanced Studies. The SAS is a unique scholarly community, and the classes and events at the school have been motivational. Evgeny Grishin and duskin drum were especially supportive as I developed my thoughts in an open lecture series. I would also like to give huge thanks to Valeria Savina, for helping our family make a home in the city, and Gulyusa Zinnat, for being such an amazing friend.

Back in England, I am very grateful for the help of Bill Sherman, Charles Burnett, Alessandro Scaffi, and Eva Miller at the Warburg Institute. Michelle O’Malley was extremely kind in accommodating my family situation when I joined the institute as a Long Term Fellow, and gave me the sort of support that distinguishes the Warburg as such a special place to be. At University College London, David d’Avray was a friendly office neighbor, and gave me guidance as I completed the manuscript. I am also grateful to John Sabapathy and Sophie Page, who were very kind in welcoming me as a colleague. My studies began at the University of Bristol, and ultimately I want to thank Anke Holdenried and Ian Wei for the teaching that set me on the path of medieval history in the first place.

Finally, I would like to thank my friends and family. Todd Foley and Sharon Ostfeld-Johns have offered incredible support, advice, and friendship over the years of this book’s development. Nothing would have been possible without the love of my mother Kim Clark, my brother Mike Jones, my partner Anne Mulhall, and our daughter Frida Jones. Finally, this book is dedicated to the memory of my father, Kevyn Jones, who sadly did not live to sell the book in his shop. Although I will never understand laughter, anything I know about it I learned from him.

Abbreviations

Acta Sanctorum J. Bollandus and G. Henschenius, Acta Sanctorum . . . editio novissima, edited by J. Carnandet et al. (Paris: Palmé, etc., 1863–).

Becket Correspondence The Correspondence of Thomas Becket, Archbishop of Canterbury, 1162–1170, edited and translated by Anne J. Duggan (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000).

Becket Materials Materials for the History of Thomas Becket, Archbishop of Canterbury, edited by James Craigie Robertson, and J. B. Sheppard, 7 vols. (London: Rolls Series, 1875–85).

BL

BN

CCCM

British Library

Bibliothèque Nationale

Corpus Christianorum: Continuatio Mediaevalis.

Gerald of Wales, Opera Giraldus Cambrensis, Opera, edited by J. S. Brewer, J. F. Dimock, and G. F. Warner, 8 vols. (London: Rolls Series, 1861–91).

PL Patrologiae cursus completus: series latina, edited by J.-P. Migne, 221 vols. (Paris: Migne, 1844–64).

Introduction

Laughter and Power in Medieval Europe

Laughter played a surprising role in the twelfth-century European imagination. Around the middle of the 1100s, chronicles began telling stories of dead children being resurrected while laughing. Histories described men being struck dumb for making blasphemous jokes, and hagiographies showed saints and kings laughing while predicting the future. At the very same moment, laughter became an important topic of philosophical, theological, and political debate. By the final decades of the twelfth century it was appearing as the principal subject of monastic treatises, miracle collections, and biblical glosses. Just as theologians at Oxford and Paris were now debating whether Jesus laughed, philosophers were beginning to define laughter as a property of the human, and writers at the great medical schools of Salerno and Montpellier were diagnosing laughter as a healing power within the body. Nowhere was the importance of laughter more hotly debated than in England, at the court of King Henry II (r.1154–89). Here, within the works of a dazzling literary renaissance, two startling figures appeared: a “laughing king” (rex ridens) and a “laughing saint” (sanctus ridens). King Henry II is perhaps most famous now for his bureaucratic legal reforms. But contemporary observers felt that laughter was just as essential as bureaucracy in the running of his government. Whether he was intervening in justice or arguing with his functionaries, we are told that Henry often preferred joking as his first line of attack. Among his critics he was famous for creating a “public spectacle of derision” (publice derisionis theatrum), inspiring joking and mockery as tools of political manipulation.1 As experienced insiders warned newcomers, when entering Henry’s court they should beware “laughter and the disgrace of failure” (risu aut ruinae turpiter), which could cost them their careers or even their lives.2 According to high ranking courtiers such as the bishops Roger of Worcester (d. 1179) and Hugh of Lincoln (d.1200), joking with the king was often the most effective way of deflating his anger and winning his support. Meanwhile Daniel of Beccles (d.c.1206), a courtier who wrote an

1 Peter of Blois, The Later Letters of Peter of Blois, edited by Elizabeth Revell (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993), letter 7, p. 43.

2 John of Salisbury, The Letters of John of Salisbury, edited by W. J. Millor, H. E. Butler, and Christopher N. L. Brooke (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986), vol. 2, Letter 176, pp. 166–7.

extensive conduct manual advising on good manners, claimed that everything he knew of wit (facete) he had learned “from Old King Henry himself.”3

From the same circles that produced this “laughing king” also emerged the figure of Thomas Becket (c. 1120–70), who writers quickly immortalized after his death as a type of “laughing saint.” Thomas had been the king’s closest intimate and Royal Chancellor, and by all accounts he was a frivolous joker in his early political life. But his career took an abrupt turn in 1162, when Henry made him archbishop of Canterbury, the highest rank in the English church. In his new post Thomas began demanding expanded ecclesiastical powers over law and taxation, at which point his relations with Henry cooled sharply. The two men burst into open war, and Thomas fled to France in exile in 1164, apparently fearing for his life. He was assassinated in Canterbury Cathedral shortly after Christmas in 1170, reportedly at the king’s will, and was canonized just three years later. A collection of hagiographies soon followed, many of which singled out Thomas’s laughter as a symbol of his defiance. In these texts Thomas was shown laughing while receiving prophecies, joking while attacking the king, and even laughing while preparing for his death. In one particularly graphic account, a French poet described Thomas’s mutilated severed head laughing back in mockery at his aggressors. And a popular folklore even sprang up, celebrating Thomas for performing a range of “amusing miracles” and miraculous jokes from beyond the grave.

Why did laughter become so important in the second half of the twelfth century? And how did contemporaries imagine it working as an attribute of both kingship and sainthood? By investigating these two connected questions as they played out at the English court, this book aims to expose the powerful role of laughter in medieval political and religious life more generally. Ultimately, I will argue that the popularity of images of the laughing Saint Thomas and King Henry rested on two crucial international developments. First, they reflected laughter’s growing reputation as a sign of transcendent moral authority within wider networks of European theology, literature, and social culture. During this period, I will suggest, descriptions of inspired laughter increasingly worked to communicate God’s emphatic and unequivocal support. More practically, I will also argue that the success of the laughing king and saint was a measure of the increasing value of humor as a political technique for maintaining and negotiating power. As we will see, however, these theoretical and practical capacities crossed over in a number of curious ways. Just as Saint Thomas’s laughter became an imaginative symbol of holy supremacy in his clash with royal power, so theological ideas of moral laughter also came to be mobilized as practical justifications for the satirical and politicized laughter of Henry’s courtiers. What made the laughter of Henry and Thomas so powerful for contemporaries, I will ultimately suggest, was that it managed to be inextricably political and theological in its impact, all at once.

3 Daniel of Beccles, Urbanus Magnus Daniel Becclesiensis, edited by J. Gilbart Smyly (Dublin: Dublin University Press, 1939), p. 92, l.2836–9.

While international in scope, this book will focus on an exceptional English court society. After the country had suffered nearly twenty years of anarchy and civil war, Henry Plantagenet came to the throne in 1154 keen to bring order and stability to his new realm. He ended up bringing a cultural renaissance as well. Among King Henry’s intimates were some of the most talented and creative Latin writers of the Middle Ages. John of Salisbury (d.1180), an experienced administrator and heavyweight intellectual, was a leading light of twelfth-century learning, writing political tracts, poems, and candid chronicles, all saturated with allusions to classical literature and philosophy. Peter of Blois (d.c.1203), a talented diplomat and paranoid nomad who worked for Henry after years of study in Paris and Bologna, produced a collection of letters that are still celebrated as some of the finest in the Latin language. Walter Map (d.c.1209/10), a satirist and raconteur, worked closely with the king and left an exuberant account of his life at court that compared the place to Hell itself. Gerald of Wales (d.c.1223), an ambitious and frustrated archdeacon, served the king closely and reflected bitterly on his experiences across a range of historical, autobiographical, and anthropological texts. Each of these courtiers, alongside many others who we will hear from throughout this book, immortalized the fiercely competitive environment of Henry’s court. Yet they all also went out of their way to stress the importance of humor. Not only did these courtiers produce a wave of popular satirical works, they also participated in unprecedented debates about laughter’s ethics, and they circulated conduct manuals, such as those written by Étienne de Fougères (d.1178) and Daniel of Beccles, that paid obsessive attention to humor and wit as matters of courtly virtue.

Yet these writers also need to be appreciated within wider continental networks of ideas. On the one hand, the turn to laughter at Henry’s court is exemplary of the “twelfth-century renaissance” that was then gripping Europe. As enthusiasm for copying and circulating ancient texts and ideas increased, works such as Suetonius’s Lives of the Caesars, Cicero’s De officiis, and the Satires of both Horace and Juvenal began to have a noticeable impact on ways of seeing humor.4 New commentaries on classical comic texts emerged in the schools of Paris, and philosophers increasingly engaged with interpretations of laughter in the works of Aristotle, Quintilian, and Seneca.5 Yet twelfth-century writers were equally enthusiastic about reaching across spatial boundaries. Courtiers such as John of Salisbury and Gerald of Wales participated in an increasingly federal international culture, drawing on a broad web of theological debates from Paris, monastic sermons from Burgundy, and rhetorical treatises from Italy, as well as saint’s lives from Flanders and love poems from Toulouse. Rather than articulating a totally

4 See for example Suzanne Reynolds, “Glossing Horace: Using the Classics in the Medieval Classroom,” in Medieval Manuscripts of the Latin Classics: Production and Use, edited by Claudine A. Chavannes-Mazel and Margaret M. Smith (London: Red Gull Press, 1996), pp. 109–10, pp. 103–18.

5 James Jerome Murphy, Rhetoric in the Middle Ages: A History of Rhetorical theory from Saint Augustine to the Renaissance (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1981), pp. 89–132.

original view of humor, they processed and intensified these continental and classical attitudes in response to their own highly unique political situation.

Focusing on laughter as a political technique, this book hopes to contribute to our understanding of a deeply transformative period in the development of England. Henry II’s reign (1154–89) was a time of unprecedented political centralization. As Henry strove to reform his government, a string of written protocols, letters, and charters came to replace the forms of personal and charismatic authority that had previously stood in their place.6 In the law the development of original writs brought wider and more uniform access to justice, while economic practices in the Exchequer became codified and scrupulously preserved in archival records.7 At this time England also experienced a transformation of religious practices. Cistercian monasteries sprang up throughout the English countryside, electrifying a new generation of young people with radical ideas of divine love and holy purity.8 In the decades after an English pope, Adrian IV, ruled in Rome (1155–9), English bishops also became increasingly involved in international church politics, fueled in part by the new schools in Paris that were now becoming the standard training grounds for an emerging clerical class.

6 On the period of transition from the reign of King Stephen, see Emilie Amt, The Accession of Henry II in England: Royal Government Restored, 1149–1159 (Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, 1993).

7 Henry’s contributions to legal reform have most recently been discussed in John Hudson, The Formation of the English Common Law: Law and Society in England from King Alfred to Magna Carta, second edition (London: Routledge, 2014), ch. 6. See also Frederick Pollock and F. W. Maitland, The History of English Law before the Time of Edward I, second edition (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1968), pp. 136–73; Doris M. Stenton, English Justice Between the Norman Conquest and the Great Charter, 1066–1215 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1964), ch. 2; Ralph V. Turner, The English Judiciary in the Age of Glanvill and Bracton, c.1176–1239 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985), pp. 17–64; and Paul Brand, “Henry II and the Creation of the English Common Law,” in Henry II: New Interpretations, edited by Christopher Harper-Bill and Nicholas Vincent (Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, 2007), pp. 215–41. On Henry’s financial reforms, see H. G. Richardson and G. O. Sayles, The Governance of Medieval England from the Conquest to the Magna Carta (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1963), pp. 216–50; G. L. Harriss, King, Parliament, and Public Finance in Medieval England to 1369 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1975), pp. 188–93. Emilie Amt, The Accession of Henry II, pp. 119–31; David Carpenter, “ ‘In Testamonium Factorum Brevium:’ The Beginnings of the English Chancery Rolls,” in Records, Administration and Aristocratic Society in the Anglo-Norman Realm, edited by Nicholas Vincent, (Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, 2009), pp. 1–28; John Sabapathy, Officers and Accountability in Medieval England, 1170–1300 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014), pp. 91–110; For more general shifts in record keeping and written mechanisms, see Michael T. Clanchy, From Memory to Written Record: England 1066–1307, second edition (Oxford: Blackwell, 1993), pp. 67–68. See also W. L. Warren, Henry II (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1973), pp. 301–17. A broader analysis appears in Brian Stock, The Implications of Literacy: Written Languages and Models of Interpretation in the Eleventh and Twelfth Centuries (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1983), pp. 30–87. For Henry II, see especially Stock’s comments on pp. 58–9.

8 On twelfth-century religious change in England, see David Knowles, The Monastic Order in England (Cambridge: The University Press, 1940); Charles Duggan, “From the Conquest to the Death of John,” in The English Church and the Papacy in the Middle Ages, edited by C. H. Lawrence (London: Burn and Oats, 1965), pp. 63–115; Brian Golding, Gilbert of Sempringham and the Gilbertine Order, c.1130–1300 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1995); Anne J. Duggan, “Henry II, the English Church and the Papacy,” in Henry II: New Interpretations, edited by Christopher Harper-Bill and Nicholas Vincent (Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, 2007), pp. 154–83; Rachel Koopmans, Wonderful to Relate: Miracle Stories and Miracle Collecting in High Medieval England (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2011); Hugh Thomas, The Secular Clergy in England, 1066–1216 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014).

Henry II’s powerful laughter can tell us a great deal about this changing political context. On the one hand, it highlights the considerable importance of contingency and flexibility in Henry’s government. Lewis Warren, Henry’s greatest modern biographer, once considered the king’s supreme achievement to be his development of an impersonal governmental machinery.9 As the historian John Le Patourel put it, Henry effectively cemented a loose collection of lands into a centralized “feudal” state.10 In more recent decades, however, historians have tended to emphasize Henry’s political spontaneity instead.11 The king’s financial policies were more reactive than proactive, according to James Holt, and his approach to legal reform was “assertive, without . . . an overall plan,” in the view of the legal historian John Hudson.12 For John Gillingham, similarly, Henry’s political decision making was ad hoc and responsive, rather than tightly planned.13 It is clear that Henry was frustrated by many of the protocols he himself had adopted for managing the affairs of state, and it is well known that his emotions often punctuated his leadership style.14 Yet laughter was also a highly productive aspect of Henry’s government, not in opposition to but rather in cooperation with his procedural reforms. By fixing problems thrown up by the governmental machinery, whether deliberately or not, the king’s laughter was able to supplement the abstract tools of power that otherwise constrained him. Within a restrictive framework of written procedure, codification, and bureaucracy, the king’s humor became powerful precisely because it represented an unmediated and irreducible authority. By counterbalancing the very methods of political centralization that enabled his empire to function, Henry’s laughter appeared as a force to shadow and complement the new powers of twelfth-century England.

Meanwhile the emergence of the laughing saint illuminates something of the changing power of the passions in twelfth-century devotion and religious politics. Among theologians of the later 1100s the body was increasingly seen as a vehicle of internal grace. Whereas a previous generation had relegated laughter to something one did in the mind rather than in the mouth, influential new theological voices, from Cistercian monks to Parisian exegetes, began arguing that bodily expressions such as laughter could channel an inner harmony and divinity. In cases like the sanctification of Thomas Becket, where spirituality and politics came to

9 Warren, Henry II

10 John Le Patourel, “The Plantagenet Dominions,” in Feudal Empires: Norman and Plantagenet (London: Hambledon Press, 1984), pp. 289–308.

11 For instance, the two edited volumes produced in the past decade: Writers of the Reign of Henry II, edited by Ruth Kennedy and Simon Meecham-Jones (New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2006), and Henry II: New Interpretations. See especially Nicholas Vincent, “The Court of Henry II,” in Henry II: New Interpretations, pp. 313–14.

12 James C. Holt, Magna Carta and Medieval Government (London: The Hambledon Press, 1985), pp. 28–34; John Hudson, The Formation of the English Common Law, p. 146.

13 John Gillingham, The Angevin Empire (London: Arnold, 2001), especially p. 116.

14 On Henry’s emotional style of kingship, see the famous study by John E. A. Jolliffe, Angevin Kingship (London: Adam and Charles Black, 1955).

intersect, the saintly nature of bodily gestures then became a uniquely powerful weapon.15 As recent studies by Martin Aurell and Hugh Thomas have shown, Becket’s minute bodily gestures were intended in the biographies to communicate a specific choreography of martyrdom.16 Laughter’s place within this bodily economy of devotion was potentially very significant, and deserves more attention.

More broadly, this book engages with a series of historiographical debates about humor’s nature and role within the wider civilization of the Middle Ages. Curiously the twelfth century has received relatively little attention from scholars of medieval humor. Specialized studies have tended to focus instead on both earlier and later texts, highlighting the philosophical impact of classical writers such as Aristotle, as well as the comic preaching practices of the mendicant orders. Writing in the late 1970s, Joachim Suchomski produced a foundational investigation that emphasized how theologians such as the Dominican Thomas Aquinas (d.1274) embraced Aristotle’s praise of eutrapelia (or “wittiness”) in their Christian ethics. Classical ideas were the key for Suchomski, who passed over the twelfth century as a period when writers “failed to integrate Antique ideas of humor into Christian teaching.”17 A decade later the great Annales historian Jacques Le Goff picked up the argument and adopted the same chronology. In an inspiring essay, Le Goff described how the contingent demands of mendicant preaching in urban centers, alongside the spread of classical rhetoric and philosophy in the universities, combined to allow theologians to embrace laughter as a mode of spiritual expression from the early 1200s onwards.18 Within this view, humor was essentially a hindrance to medieval church authorities until they were able to tame and repurpose it as a tool of orthodoxy.

This narrative of a thirteenth-century “Christianization” of laughter has persisted across a range of interdisciplinary approaches in the past decades.19 Jeannine

15 On the impact of theological ideas on court culture, see Fiona Whelan, The Making of Manners and Morals in Twelfth-Century England: The Book of the Civilised Man (London: Routledge, 2017), especially pp. 113–50.

16 Martin Aurell, “Le Meurtre de Thomas Becket: Les Gestes d’un Martyre,” in Bischofsmord im Mittelalter, Murder of Bishops, edited by N. Fryde and D. Reitz (Göttingen: Ruprecht, 2003), pp. 187–210; Hugh Thomas, “Shame, Masculinity, and the Death of Thomas Becket,” Speculum 87: 4 (October 2012), pp. 1050–88.

17 Joachim Suchomski, “Delectatio” und “Utilitas”: Ein Beitrag zum Verständnis mittelalterlicher komischer Literatur (Munich: Francke, 1975), pp. 30–5, pp. 55–61, and p. 65.

18 Jacques Le Goff, “Laughter in the Middle Ages,” in A Cultural History of Humour: From Antiquity to the Present Day, edited by Jan Bremmer and Herman Roodenburg (Cambridge: Polity Press, 1997), pp. 40–53, originally published as “Rire au Moyen Age,” Les Cahiers du Centre de Recherches Historiques 3 (1989), pp. 1–19. See also Jacques Le Goff, Saint Francis of Assisi, translated by Christine Rhone (London: Routledge, 2004), pp. 122–3. For a very similar view, published slightly before Le Goff, see Irven M. Resnick, “ ‘Risus Monasticus’: Laughter and Medieval Culture,” Revue Bénédictine 97 (1987), pp. 90–100. While Resnick discusses changes in philosophy and mainly monastic theology, he does not approach the issue as a broad historical problem in the same way as Le Goff.

19 Some insightful essays on laughter in medieval literature have appeared in the last twenty years, yet while they have shed light on theoretical and textual dynamics of laughter in texts, they have done little to challenge the narrative of a “Christianization” in the 1200s. For example, Risus Mediaevalis: Laughter in Medieval Literature and Art, edited by Herman Braet, Guido Latré, and Werner Verbeke

Horowitz and Sophia Menache expanded the view in their influential book L’humour en chaire, illuminating how thirteenth-century mendicant preachers appropriated humor as a tool of moral instruction, adapting it to the particular demands of an urban audience.20 Jean Verdon echoed these points in his broad history of the subject, again identifying a Christian turn to laughter in the lives of Saints Francis of Assisi and Thomas Aquinas.21 Moving away from texts, both Willibald Sauerländer and Paul Binski have extended this chronology into the visual arts. Demonstrating a multiplication of positive Christian images of laughter during the thirteenth century, they have persuasively suggested that the 1100s were instead dominated by images of laughing devils and demons.22 In a sign of growing consensus across disciplines, a recent collection of essays (published to accompany an exhibition in Mainz) outlined a similar change in Christian debates about laughter in the decades after 1200.23 Once again, these new studies overwhelmingly stressed the role of Aristotle’s philosophy and its thirteenth-century scholastic interpreters in adapting laughter as a positive Christian theme. Where the twelfth century has been the subject of debate, it has often been described as a time of growing anxieties about the abuses of humor. Olga V. Trokhimenko’s important recent book, Constructing Virtue and Vice, has added a vital layer of nuance to the “Christianization” narrative. Pointing to increasing concerns about laughter (particularly women’s laughter) in ecclesiastical and courtly texts from the 1150s onwards, Trokhimenko’s work highlights how, despite the resurgence of Aristotle, theologians continued to be deeply uncomfortable in dealing with the issue. As Christian thinkers began putting more emphasis on the role of the body in devotion, she argues, many within the Church paradoxically fought to control laughter. So, while writers such as Aquinas celebrated it as a necessary human bodily expression, others such as Vincent of Beauvais continued

(Leuven: Leuven University Press, 2003); Grant Risee? The Medieval Comic Presence, edited by Adrian P. Tudor and Alan Hindley (Turnhout: Brepols, 2006); Medieval English Comedy, edited by Sandra M. Hordis and Paul Hardwick (Turnhout: Brepols, 2007).

20 Jeannine Horowitz and Sophia Menache, L’humour en chaire: Le rire dans l’Eglise médiévale (Geneva: Labor et Fides, 1994). See especially, pp. 243–4. This argument is reiterated in Georges Minois, Histoire du Rire et de la Derision (Paris: Fayard, 2000). Minois discusses the Christianization of laughter at pp. 95–215. See also Jacques E. Merceron, “The Sacred and the Laughing Body in French Hagiographic and Didactic Literature of the Middle Ages,” in Risus Sacer – Sacrum Risible, Interaktionsfelder von Sakralität und Gelächter im kulturellen und historischen Wandel, edited by Katja Gvozdeva and Werner Röcke, pp. 101–16 (Bern: Peter Lang, 2009), especially pp. 103–4.

21 Jean Verdon, Rire au Moyen Age (Paris: Perrin, 2001), pp. 24–9.

22 Willibald Sauerländer, “Vom Gelächter des Teufels zur Ironie der Philosophen,” Jahrbuch der Bayerischen Akademie der Schönen Künste 13 (1999), 30–70; Paul Binski, ‘The Angel Choir at Lincoln and the Poetics of the Gothic Smile,’ Art History 20: 3 (1997), pp. 350–74. For an updated take on these debates in art history, see Monika E. Müller, “Das Lachen ist dem Menschen eigen : Seine Darstellung in der Kunst des Mittelalters,” in Seliges Lächeln und höllisches Gelächter: Das Lachen in Kunst und Kultur des Mittlealters, edited by Winifried Wilhelmy, pp. 68–91 (Regensburg: Schnell und Steiner, 2012).

23 Seliges Lächeln. See particularly Winifried Wilhelmy, “Das leise Lachen des Mittelalters – Lächeln, Lachen und Gelächter in den Schriften christlicher Gelehrter (300-1500),” pp. 38–55.

to condemn it, defiantly citing the authority of patristic writers.24 Trokhimenko is certainly correct to suggest that the thirteenth century saw an enduring hostility to laughter, and her emphasis on anxiety takes the debate to a level of complexity that gets us beyond more straightforward ideas of “Christianization.” Nevertheless, as Trokhimeko concedes, her work is limited by its literary and philological focus. Beyond the material she addresses, there is much that remains to be said about the miraculous and awe-inspiring laughter that gripped many hagiographers, monks, medical writers, and biblical exegetes in the 1100s.

Medievalists have long recognized the productive importance of humor in Christianity.25 Most notably, Martha Bayless has uncovered a lively culture of comedy in a great variety of ecclesiastical texts.26 Exploring how medieval clerics produced mock saints’ lives and parodic sermons, mostly for an ecclesiastical audience, Bayless has argued that this material was primarily meant to be fun. She rejects the idea that playful imitations of serious religious forms were automatically “subversive,” and criticizes Mikhail Bakhtin’s theory of carnival for suggesting that laughter was overly restricted and circumscribed in medieval religious life.27 Instead, Bayless emphasizes how laughter and comic play existed alongside serious Christian practices, and advises that the comic should be considered as an intrinsic part of medieval devotion, rather than as its natural opponent. To paraphrase another scholar who has recently extended the same position, laughter can be best understood as a “universal presence” in medieval life, an impulse waiting to burst through rules and codes at any given time.28

But the laughter at Henry II’s court suggests something more substantial than either fun or comic relief. What makes the saintly laughter of Thomas Becket so intriguing is that it was understood as having a holy, even mystical potential all of its own.29 We are long overdue a study that takes the role of laughter and humor in medieval sanctity seriously. Work that has been done so far on this topic has typically focused on the later figure of Saint Francis of Assisi (d.1226). According to Carlo Ginzburg, Franciscan “holy humor” worked above all by confounding expectations in acts of “carnivalesque” inversion, such as kissing lepers and rolling

24 Olga V. Trokhimenko, Constructing Virtue and Vice: Femininity and Laughter in Courtly Society (ca. 1150–1300) (Göttingen: V&R Unipress, 2014), pp. 63–89. Her major argument here is stated on p. 78.

25 For an overview, see Ingvild Saelid Gilhus, Laughing Gods, Weeping Virgins: Laughter in the History of Religion (London: Routledge, 1997), pp. 60–101.

26 Martha Bayless, Parody in the Middle Ages: The Latin Tradition (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1996).

27 Mikhail Bakhtin, Rabelais and His World, translated by Hélène Iswolsky (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1968).

28 Stefan Bießenecker, “A Small History of Laughter, or When Laughter Has to be Reasonable,” in Behaving Like Fools: Voice, Gesture, and Laughter in Texts, Manuscripts, and Early Books, edited by Lucy Perry and Alexander Schwarz (Turnhout: Brepols, 2010), pp. 193–222.

29 As Jacques Merceron has intimated, this kind of “rire sacralisant” alluded ultimately to “a future of eternal bliss.” Jacques E. Merceron, “The Sacred and the Laughing Body in French Hagiographic and Didactic Literature of the Middle Ages,” in Risus Sacer – Sacrum Risible: Interaktionsfelder von Sakralität und Gelächter im kulturellen und historischen Wandel, edited by Katja Gvozdeva and Werner Röcke (Bern: Peter Lang, 2009), pp. 101–16; p. 108.

with pigs, that challenged human dignity.30 If the saintly humor of Francis is seen as transcendent in these accounts then, as John Saward has argued, this is because it defied social norms, working within a tradition of “holy folly” that held foolishness and non-conformity as humble virtues.31 Yet the saintly laughter attributed to Thomas Becket appears to have been far more aggressive and political in nature. Transcending the human institutions that attempted to limit his “divine” authority,32 Becket’s laughter represents a uniquely political, bellicose form of saint’s laughter that has yet to be studied in its own right.

Another principal aim of this book is to assess the role of laughter in medieval politics. Historians have long acknowledged the importance of humor in smoothing political tensions, although they have usually cast it in the rather straightforward role of a means to an end.33 One exception is Stephen Jaeger’s work on medieval courtliness, which has drawn attention to the more complex psychological ways that humor operated in medieval political conflicts.34 Courtiers such as John of Salisbury, Jaeger argues, used irony as a way of distancing themselves from a culture of debate that encouraged fierce backbiting and a nervous consensus. Irony became a mode of survival in this environment, Jaeger argues, as well as an indirect means for offering a more oblique form of court critique.35 In a similar spirit, Hugh Thomas’s recent article in Speculum has stressed how Henry’s court itself produced a culture in which humiliation had a huge impact on political standing.36 While these are important observations, it is clear that more study needs to be done to do justice to the many nuanced and powerful ways that humor worked in medieval political culture. We still lack any real understanding of how laughter functioned in medieval law, for instance, or in medieval bureaucracy, or in moments of brutal political violence. The political regime of Henry II, which specialized in all three, should provide the perfect opportunity to begin taking these issues further.

Moving in scope from broad to narrow, this book has two parts. Chapters 1 and 2 will investigate laughter’s growing political and religious power in twelfthcentury thought and literature. Taking on the widest range of material available to

30 Carlo Ginzburg, “Folklore, magia, religione,” in Storia d’Italia, vol. 1: I caratteri originali (Turin: Einaudi, 1972), pp. 603–76, pp. 615–16.

31 John Saward, Perfect Fools: Folly for Christ’s Sake in Catholic and Orthodox Spirituality (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1980), pp. 84–9. On this issue, see also the excellent work in Max Harris, Sacred Folly: A New History of the Feast of Fools (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2011). On this topic, see also Peter J. A. Jones, “Humility and Humiliation: The Transformation of Franciscan Humour, c.1210–1310,” Journal of Cultural and Social History 15: 2 (2018), pp. 155–75.

32 For this analysis of Christian laughter, see Patrick Laude, Divine Play, Sacred Laughter, and Spiritual Understanding (New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2005), pp. 142–3.

33 See for example Peter Godman, “The Archpoet and the Emperor,” in Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, vol. 74 (2011), pp. 31–58, p. 57.

34 C. Stephen Jaeger, The Origins of Courtliness: Civilizing Trends and the Formation of Courtly Ideals, 939–1210 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1985), especially p. 168.

35 C. Stephen Jaeger, “Irony and Role-Playing in John of Salisbury and the Becket Circle,” in Culture politique des Plantagenêt (1154–1224): Actes du Colloque tenu à Poitiers du 2 au 5 mai 2002, edited by Martin Aurell (Poitiers: Civilisation Médiévale, 2003), pp. 319–31.

36 Hugh Thomas, “Shame, Masculinity,” pp. 1050–88.

Henry’s courtiers, these two chapters represent a broad interrogation of laughter’s significance in the twelfth century. By next focusing on Henry’s court and the king’s conflict with Thomas Becket, the second part of the book (Chapters 3 to 5) will explore how this emerging significance translated into acts of political, saintly, and sovereign power. While the first part of the book, therefore, looks at wider concepts and descriptions of laughter across a great many texts, the second part turns to examine laughter in action within the smaller set of letters, chronicles, and histories that survive from Henry II’s court, as well as the biographies and miracle collections of Saint Thomas produced in the decade or so after his death.

We will hear, in the first two chapters of the book, from the many intellectuals and poets whose ideas laid the groundwork for images of powerful laughter at Henry’s court. Through a genealogical study of intellectual debates known within the king’s circle, the first chapter examines the changing place of laughter in philosophical, exegetical, monastic, rhetorical, satirical, and medical discussions throughout the 1100s. Although this is a broad range of material, there are a number of key convergences. As I will suggest, the way laughter was talked about in theology had close parallels to the way it was discussed in rhetoric, in medicine, and in philosophy. A concern that united these different debates was the role of the body. As the evidence tentatively suggests, writers of all kinds gradually came to embrace embodied laughter as a vehicle for Christian devotion and grace, as well as a potent expression of political power.

Abstract ideas, however, do not give the whole picture of laughter’s place in the imagination. My second chapter turns to look at laughter’s changing role in twelfth-century narrative. Building on the classic work of Philippe Ménard, as well as the more recent observations of Gerd Dicke and Albrecht Classen, this chapter looks at a wealth of historical, poetic, hagiographic, and epic literature as a way of surveying the different narrative motifs of laughter that appeared in texts from the 1100s.37 Exploring how laughter emerged as a sign of mystical contact, as well as a sin for which people were divinely punished, I argue that it began to acquire a prophetic and political potential for revelation in narrative from the 1130s onwards. Most importantly, laughter came to be associated with the power of prophetic revelation in the lives of saints such as Edward the Confessor, and with miraculous disease and charismatic authority in chronicles of kings such as William Rufus. On the one hand these developments owed much to the new intellectual perspectives on laughter that I described in the previous chapter. Yet I will also emphasize how motifs from classical texts, such as Suetonius’s Lives of

37 Philippe Ménard, Le Rire et le sourire dans le roman courtois en France au Moyen Age (1150–1250) (Geneva: Librairie Droz, 1969); Albrecht Classen, “Laughter as an Expression of Human Nature in the Middle Ages and the Early Modern Period: Literary, Historical, Theological, Philosophical, and Psychological Reflections,” in Laughter in the Middle Ages and Early Modern Times (New York: De Gruyter, 2010), pp. 1–140; especially pp. 56–60.

the Caesars, left a profound stamp on how charismatic traits such as laughter were immortalized in the historical record.

My third chapter focuses on the social and political world of the royal court. Here, as I will suggest, laughter’s emerging connections to sublime revelation fused with a cynical political culture to create a twin ethic of humor. First of all, it came to be prized as a weapon for exposing “truths” behind the masks and hierarchies of court life. At the same time that conduct manuals were urging courtiers to cultivate wit above other faculties, veterans in royal service were reminding one another to joke and laugh when in the company of the king. In a setting where courtiers were terrified of speaking the truth to power, it seems that laughter, as a non-explicit act, became a unique way of showing the un-showable and saying the unsayable. On the one hand, this ethic could be edifying, in the form of erudite satires or witty observational humor. On the other hand, however, it could also be spiteful or corrosive, in the form of humiliating derision or career-ruining jokes. Through the formidable tension between these positive and negative ethics, I argue, Henry’s court writers ultimately created a space for images of laughing saints and laughing kings to have especially powerful effects.

Working with these ideas, my fourth chapter looks at the dynamic role of laughter in the retrospective construction of Thomas Becket’s sanctity. Reading in particular the hagiographies and miracle collections produced after Becket’s death, I investigate the curious prominence of laughter in the cult of his sainthood. Becket laughed and joked before he was martyred, he was reputed to have played jokes from beyond the grave on unsuspecting pilgrims, and he was even celebrated for making people laugh as he miraculously brought them back from the dead. Investigating how and why writers came to be obsessed with Saint Thomas’s laughter, this chapter highlights how his reputation for courtly jocularity was recast as one of his defining saintly virtues, and how in the process the political codes of laughter at Henry’s court were translated into saintly practices.

Finally, the fifth chapter approaches the image of the laughing king himself, Henry II. In a series of close readings of moments when the king was shown laughing and joking while intervening in law, during diplomatic confrontations, and in his dealings with the Church hierarchy, this chapter suggests that humor became an inadvertent tool of Henry’s sovereign exceptionalism. As I show, in Henry’s government humor circumscribed tensions between process and presence, allowing the king essentially to subvert and transcend his own network of written codes and rules through the ambiguity of laughter. Yet Henry’s laughter was also a textual effect, one meant to communicate to readers a distinct image of sovereign authority. Picking up on intellectual discourses that dignified joking as a truth-telling device, as well as on poetic ideas of laughter as a mouthpiece for divine authority, writers of Henry’s reign ultimately fixated on the image of laughing kingship as it provided a unique way of reinstating charismatic, or sublime, royal authority within the course of their narratives.

Before beginning, it is necessary to establish a few working definitions. Perhaps most important is the definition of laughter. It is fair to say that laughter is both a bodily reaction and a social sign. It can be triggered by humor, surprise, joy, anxiety, and occasionally by fear. In the twelfth century, it was also said to be triggered by prophecies, by miracles, and by a particular hyperactivity of the spleen. One of the aims of this book is to set aside modern definitions and try to uncover what laughter meant in medieval society. But this can lead to some confusion. Today we make a clear distinction between “laughter” and “humor,” but in the texts of the 1100s this was not the case. As no specific word for “humor” was available in medieval Latin, writers frequently used the word risus, along with the related verb ridere, to designate both the act of laughter and the process of making others laugh.38 Joking was often described, vaguely, as an act of “hilaritas” (cheerfulness), as a type of “levitas” (lightness), or else as a moment of “scurrilitas” (buffoonery). Working with this material, I have been cautious throughout this book to highlight distinctions between the social act of laughter, the use of humor, and more generic descriptions of good cheer. It is important to observe, however, that medieval writers did not always make these same distinctions themselves.

One boundary that was closely observed was laughter’s degree of magnitude, which writers usually measured on a spectrum from gentle smiling to raucous howling. Although a few translators have occasionally preferred to render risus as “smile,” this does not fit twelfth-century usage. When Latin writers in the 1100s wanted to convey smiling, they usually described a person as showing a hilaris vultus, or else they adopted the verbs subridere and arridere. The word Risus, for these writers, was reserved for the noisy and more bodily act of laughing. At the other end of the spectrum, a more charged word in the medieval vocabulary was cachinnum, which almost always carried the meaning of a loud cackle or a vulgar laugh.

I should also define what I mean by Henry’s court, and, by extension, “England.” Henry’s court can expand or contract significantly depending on how we define it. At the very top, the arch courtiers can be identified as Robert of Beaumont (d.1168), Richard de Lucy (d.1179), and Ranulf de Glanvill (d.1190), nobles who Henry employed as Chief Justiciars. Other key figures were the Royal Chancellors, Geoffrey Ridel (d.1189) and, notoriously, Thomas Becket. But while the king had relatively few central office holders, the court entourage was swollen with dozens of writers, jongleurs, and domestics, as well as hundreds of bureaucrats, accountants, and functionaries.39 For the purposes of this study, I have limited my definition of “the court” to the circle of individuals who knew the king personally, who participated in the social and political life of his entourage, and who left some kind of record of their experiences. While this is certainly a narrow definition, it has the

38 For examples of this ambiguity in action, see Gilbert of Poitiers, Commentaria in Librum de Duabus Naturis et una Persona Christi, PL vol. 64, Natura, col. 1364B; and Alan of Lille, Regulae Theologicae, PL, vol. 210, number 101, cols. 675C-676A.

39 Egbert Türk, Nugae curialium: Le règne d’Henri II Plantagenêt (1145–1189) et l’ethique politique (Geneva: Libraire Droz, 1977), pp. 6–7.

advantage of referring to a relatively coherent, focused, and self-aware group. This was a literate community close to the king, made up of individuals who self-identified as “courtiers” (curiales), and who consciously engaged in conversations about conduct, social etiquette, and power within what they understood as a court environment. Although writers such as John of Salisbury and Walter Map may not have overlapped in real time, when they wrote about how to behave in the presence of the king they nevertheless engaged in shared debates about the ethics and practices of being a member of Henry II’s entourage.40

All of this took place in a space that we may call the “Angevin Empire.”41 Alongside the Kingdom of England, Henry II inherited the Dukedom of Normandy from his mother, and the County of Anjou from his father. Following his marriage to Eleanor of Aquitaine (d.1204), Henry also acquired control of the Duchy of Aquitaine and the County of Poitou. Eleanor had been the wife of Henry’s rival King Louis VII of France, and this marriage was initially a strategic triumph in strengthening Henry’s territorial claims.42 Through later military conquests Henry added Gascony, Brittany, and Ireland to an empire that stretched from the Pyrenees to the Scottish borderlands. Henry’s court was therefore an international entourage in constant flux, moving between England and parts of France to the papal curia and beyond. They wrote in Latin, spoke mostly in French, and read works from around the European intellectual community. In many ways “England” does not quite do justice to this vast political and cultural space. Yet for all the court’s itinerancy, the two major theaters for much of the laughter in this book—Henry’s expansion of law and administration, and his conflict with Thomas Becket—both took place in England. While I am concerned with transnational ideas, therefore, England remains both the heart and center of this book’s discussion.

Another issue is one of emphasis. If laughter was so important at Henry’s court, what about other bodily expressions, such as weeping or the gnashing of teeth? On the one hand it is clear that the upsurge of interest in laughter ran in parallel to other changes to the body’s role in medieval society. Excellent work has been done by scholars such as Kimberley-Joy Knight and Susan Kramer, for instance, showing the importance of tears in late twelfth- and early thirteenth-century devotion.43 As Katherine Harvey has shown, a “tear-drenched” hagiography conveyed a

40 This point is also made in Nicholas Vincent, “The Court of Henry II,” in Henry II: New Interpretations, p. 320.

41 John Gillingham, The Angevin Empire.

42 For recent work on Eleanor, see Bonnie Wheeler and John C. Parsons, eds., Eleanor of Aquitaine: Lord and Lady (New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2003); Ralph Turner, Eleanor of Aquitaine (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009); Colette Bowie, The Daughters of Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitaine (Turnhout: Brepols, 2014).

43 Kimberley-Joy Knight, “Si puose calcina a’ propi occhi: The importance of the Gift of Tears for Thirteenth-Century Religious Women and their Hagiographers,” in Crying in the Middle Ages. Tears of History, edited by Elina Gertsman (London: Routledge, 2011), pp. 136–55; Susan R. Kramer, Sin, Interiority, and Selfhood in the Twelfth-Century West (Toronto: Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies, 2016), pp. 55–82.