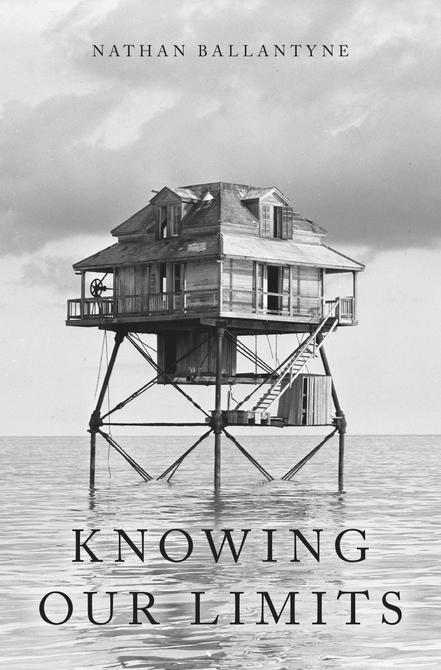

Knowing Our Limits

NATHAN BALLANTYNE

3

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

© Oxford University Press 2019

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Ballantyne, Nathan, author.

Title: Knowing our limits / Nathan Ballantyne.

Description: New York : Oxford University Press, 2019. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019006877 (print) | LCCN 2019980862 (ebook) | ISBN 9780190847289 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780190847296 (ebook) | ISBN 9780190847302 (updf) | ISBN 9780190847319 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: Knowledge, Theory of.

Classification: LCC BD201 .B35 2019 (print) | LCC BD201 (ebook) | DDC 121/.2—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019006877

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019980862

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

Printed by Sheridan Books, Inc., United States of America

For my family

My thoughts!—It is the building a house for them that troubles me.

Joseph Joubert (1754–1824), Pensées, published posthumously

Every thing has its own limits, a little centre of its own, round which it moves; so that our true wisdom lies in keeping to our own walk in life, however humble or obscure, and being satisfied if we can succeed in it. The best of us can do no more, and we shall only become ridiculous or unhappy by attempting it. . . . An overweening vanity or self-opinion is, in truth, often at the bottom of this weakness; and we shall be most likely to conquer the one by eradicating the other, of restricting it within due and moderate bounds.

William Hazlitt, “On the Shyness of Scholars,” 1827

Vanity and vexation close every inquiry: for the cause which we particularly wished to discover flies like the horizon before us as we advance. The ignorant, on the contrary, resemble children, and suppose, that if they could walk straight forward they should at last arrive where the earth and clouds meet. Yet, disappointed as we are in our researches, the mind gains strength by the exercise, sufficient, perhaps, to comprehend the answers which, in another step of existence, it may receive to the anxious questions it asked.

Mary Wollstonecraft, A Vindication of the Rights of Women, 1792

A man’s got to know his limitations.

Clint Eastwood, in the 1973 action thriller Magnum Force

Acknowledgments

While writing this book, I accumulated debts to many people for helpful conversations and written comments on draft chapters. There are too many people to thank, but let me mention a few names here.

I am grateful to Alex Arnold, Andrew Bailey, Matthew Ballantyne, Michael Bergmann, E.J. Coffman, Stewart Cohen, Sorana Corneanu, Thomas Crisp, Carlo DaVia, Dennis Des Chene, Peter Ditto, Joshua Dolin, David Dunning, William Dyer, Ian Evans, Marcello Fiocco, Bryan Frances, Daniel Greco, Stephen Grimm, Michael Hannon, John Heil, Terry Horgan, Daniel HowardSnyder, Xingming Hu, Tim Kenyon, Nathan King, Hilary Kornblith, Charlie Lassiter, Keith Lehrer, Kirk Lougheed, Michael Lynch, Jonathan Matheson, Andrew Moon, Blake Roeber, Patrick Rysiew, David Schmidtz, Norbert Schwarz, Roy Sorensen, Mark Timmons, Justin Tosi, Greta Turnbull, Joseph Vukov, and anonymous reviewers. A number of friends, former teachers, and colleagues shared insightful feedback on the project as well as gestures of encouragement: Jason Baehr, David Christensen, Paul Gooch, Peter King, Klaas Kraay, Sydney Penner, Andrew Rotondo, and Jada Strabbing. And I ought to single out three people who read more rough draft material than is right or safe: Peter Seipel, Shane Wilkins, and Benjamin Wilson. Peter and Shane commented tirelessly on the manuscript, made it better, and were sympathetic to the project when I found myself wondering what on earth I had gotten myself into. Ben offered wise counsel, keen questions, and support from false start, to start, to finish. His writerly powers and comedic instincts are matchless among former Junior Resident Fellows of Massey College.

Draft versions of different chapters were tested out on audiences at Boston University, Bowling Green State University, Loyola Marymount University, Ryerson University, University of Arizona, University of California at Irvine, University of Connecticut, University of Southern California, University of Tokyo, and Washington University in St. Louis. Thanks to audience members for discussions during Q&A sessions.

While I was at work on this project, my research assistants at Fordham University helped me hunt down sources and scholarly curiosities. They are Johnny Brennan, Noah Hahn, Allysa Lake, Joe Morton, Justin Reppert,

Luke Schumacher, and Nicholas Sooy. Thanks to Alison Shea at Fordham’s Law Library for her help cracking the case of the butcher jurors. For ad hoc translation advice, I turned to Carlo DaVia, Peter King, and Shane Wilkins. Johnny Brennan translated from German the Goethe epigraph in Chapter 8. Suzie Appenzeller and Margaret Donovan, who expertly manage the dayto-day affairs of Fordham’s Philosophy Department, were invariably knowledgeable and kind whenever I needed help.

I taught graduate seminars at Fordham where my PhD students heard about some of the arguments that ended up in these pages. Thanks to all of my students for their questions and input, especially Samuel Kampa and Coran Stewart, who gave me sharp and detailed feedback on draft chapters. Sam took a careful look at the whole manuscript during the copy-editing stage and beat me in a contest to catch my typos.

I am grateful both to my editor at Oxford University Press, Lucy Randall, for enthusiastically supporting my project, and to Hannah Doyle for her guidance throughout the production process.

Earlier versions of a few chapters appeared elsewhere. Chapter 5 began life as “Debunking Biased Thinkers (Including Ourselves),” 2015, Journal of the American Philosophical Association 1 (1): 141–162. Most of Chapter 6 appeared earlier as “Counterfactual Philosophers,” 2014, Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 88 (2): 368–387. Chapter 7 is based on “The Significance of Unpossessed Evidence,” 2015, The Philosophical Quarterly 65 (260): 315–335. Chapter 8 is a lightly brushed-up version of “Epistemic Trespassing,” 2019, Mind 128 (510): 367–395. For permission to reproduce some material from those articles, I acknowledge Cambridge University Press, John Wiley & Sons, and Oxford University Press. Thanks also to Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc. for allowing me to use as an epigraph an excerpt from the 1973 film Magnum Force.

My work was generously supported by the John Templeton Foundation, the University of Connecticut’s Humanities Institute, and Fordham University. Thanks are due to Alex Arnold, Eva Badowska, John Churchill, John Drummond, John Harrington, Michael Lynch, and Michael Murray.

If I could sit at my desk and start again on the first blank page, I suspect I would do it all differently, except for the music that animated my writing sessions. I am partial toward “North German” music—Sweelinck, Schütz, Buxtehude, Bruhns, and Johann Sebastian Bach—as well as Canadian music—Oscar Peterson, Glenn Gould, Lenny Breau, Angela Hewitt, The Tragically Hip, Propagandhi, and The Weakerthans.

I am grateful to my whole family for their companionship and thoughtfulness, and for forgiving me for the times when I should have been “there” but was working instead. My parents, Brenda and John, have been unfailingly supportive of my efforts in all things over the years and filled with love and enthusiasm. I also want to thank my grandmother, Betty Ballantyne-Brown, and my late grandfather, Frank Dicks (1932–2016), for kindness, generosity, and fishing trips.

I was confronted by my limits more than once while working on this project, but I didn’t have to rely on my own abilities to keep going. My wife, Jennifer, and our daughter, Clara, cheered me on and kept me grounded. Jennifer was a judicious and patient sounding board for ideas and encouraged me to cultivate the right attitude toward writing about academic epistemology. Clara once asked me whether the book’s cover could feature a picture of her riding a Stygimoloch. Her arrival on the scene prompted me to try to say something about my chosen academic field that I didn’t know how to say. Without Clara, this work would have been completely different.

There’s an old observation, attributed to Blaise Pascal, about authors and their books: “Certain authors, speaking of their works, say: ‘My book,’ ‘My commentary,’ ‘My history,’ and so on. They resemble middle-class people who have a house of their own and always have ‘My house’ on their tongue. They would do better to say: ‘Our book,’ ‘Our commentary,’ ‘Our history,’ and so on, because usually there is in their books more good from others than from themselves.” This book owes so much to many people—but most to my family. I dedicate it to them.

Nathan Ballantyne June 2019

Epistemology and Inquiry

It is good, from time to time, to view the present as already past, and to examine what elements it contains that will add to the world’s store of permanent possessions, that will live and give life when we and all our generation have perished. In the light of this contemplation all human experience is transformed, and whatever is sordid and personal is purged away.

Bertrand Russell, “On History,” 1904

Epistemology is careful reflection on inquiry. When we inquire, we use evidence to answer questions. One inescapable fact is that we are all imperfect inquirers. We are often overconfident, prejudiced, muddled, and wrong. Improving our intellectual life takes work. But how should we direct our efforts? What can we do to become more reasonable and reliable? That is where epistemology figures in. We need guidance to overcome our intellectual shortcomings, and my central thesis in this book is that epistemology can provide that guidance.

An inquiry-guiding conception of epistemology has played an important role in the history of philosophy, though it is not so well represented today in the field of professional epistemology. Let me briefly describe two historical roots of the present work.

Some philosophers in early modern Europe played a central role in their world’s intellectual affairs. After the gradual breakdown of the widespread religious and moral consensus of the Middle Ages, people faced a crisis. The sources of authority that had ordered human life for centuries had eroded. Many people found traditional values and ideas doubtful. Some philosophers tried to fill the intellectual vacuum by rejuvenating inquiry. They turned to questions about methods, knowledge, and reasonable opinion. They tried to build new foundations for science and medicine, challenge superstition and dogmatism, and draft blueprints for a more stable society. We now

think of their efforts as ringing in the ages of “Scientific Revolution” and “Enlightenment.” An important part of philosophers’ work was what John Locke called the “first inquiry”—the attempt, as Locke put it, “to examine our own Abilities, and see, what Objects our Understandings were, or were not fitted to deal with” (1975 [1690], 7). Philosophers often saw themselves as using truths about inquiry to promote the sciences and human flourishing.

In Vienna during the early decades of the twentieth century, a small but influential group of European intellectuals met regularly to talk. They discussed philosophy, science, and society. They called themselves Der Wiener Kreis the Vienna Circle. What united them was empiricism. By starting with the idea that experience is the only source of knowledge, they wanted to articulate and defend what they called the “scientific world-conception.” Although some members of the Vienna Circle were academics, the group was not merely trying to settle scholarly scores; many of them hoped that philosophy and science would transform the social and political order. Some members took it as their goal to “unify” and coordinate the sciences in the service of effectively planning modern life. Reaching out in public lectures and writings, they conveyed the scientific world-conception to audiences. They hoped that their ideas could help counteract the rise of totalitarian regimes. After all, mistaken epistemological ideas threaten to usher in dangerous social consequences. During the 1930s, politicians and propagandists used ideas such as “highest duty” and “national community” to whip the masses into a frenzy and to launch armies of goose-stepping soldiers. Members of the Vienna Circle thought clear-eyed empiricism would eliminate such perilous nonsense and help to preserve civil society. One historian remarked that the Circle sought nothing less than “to help fulfill the promise of the eighteenthcentury French Enlightenment” (Reisch 2005, 3).

There are many other examples of thinkers seeking to use reflection on inquiry as a tool to improve inquiry and thereby our lives. I offer this book as a modest contribution to the long tradition of what I’ll call regulative epistemology the kind of epistemology that aims to provide guidance for inquiry.

My path to writing this book has been roundabout. Here’s one little habit that led me here. On a quiet afternoon, I like to choose a well-regarded academic philosophy journal from the library shelves and skim fifteen or twenty issues from the first half of the twentieth century. It usually takes me until dinner. I glance at articles by scholars whose names I have mostly never heard of. I wonder about the origins of now-forgotten theoretical agendas

and debates. At high speed, I watch a great parade of philosophical research pass by. I have tried to fathom the quantity of the ambition and the striving represented by these many thousands of pages. How many late nights, how many waste bins loaded with crumpled-up drafts, did all of this take? Is this what it’s like to view philosophers’ lives from the outside? I’m confronted in these acid-free pages with questions about my own working days. One keystroke at a time, I add a few more pages to the growing heap of work on academic philosophy. But what is the point of these efforts? Is it more than paying bills, or seeking promotion, or trying to eke out a place in a professional field?

So I’ve thought a little about what professional epistemologists do. In their work, they reflect on inquiry carefully. What is the purpose of their reflection? Which parts of inquiry matter to them? What is epistemology for? For me, these are disquieting questions. I bring no conclusive answers. Yet I am often moved by the idea that careful reflection on inquiry could have great value if it makes us less imperfect in our attempts to figure things out.

In the first three chapters of this book, I introduce regulative epistemology by examining its nature and scope, a brief part of its history, and its practical ambitions for guiding inquiry. The present chapter orients us toward the place of regulative epistemology within the contemporary scene. First, I describe some general trends in recent academic epistemology, explaining why the field often does not share the concerns of regulative epistemology (sections 1–4). Then I describe how regulative epistemology requires contributions from scientific and humanistic researchers who focus on inquiry. As I explain, there’s a vital role for epistemologists to play in the project (sections 5–7).

1. What Is Professional Epistemology?

In 1986, a group of epistemologists met at Brown University to celebrate the seventieth birthday of a renowned practitioner of their craft, Roderick Chisholm (1916–1999). The philosophers sat together in a large seminar room and listened to presentations. Principles and arguments in premiseconclusion form were written in chalk on a blackboard. During Q&A periods, speakers and audience members went back and forth in critical exchange. One speaker joked that if a bomb had been dropped on the building where the group had met, the profession of epistemology in America would cease to exist. Professional epistemology has only ever been a relatively slight

thing. Even today, all of the professional epistemologists would probably fit into the grand ballroom at a corporate conference hotel.

What do epistemologists do? In recent textbooks and encyclopedias, epistemology is defined as the branch of philosophy that investigates questions about the nature and scope of knowledge and reasonable belief.1 The subject matter of contemporary epistemology is widely thought to be general, abstract epistemic concepts or epistemic states themselves. Practitioners aim to describe propositional knowledge, epistemically justified belief, and evidence. They puzzle over radical skeptical challenges and evaluate responses. They detail the character traits of virtuous thinkers.

But the vast majority of work in contemporary professional epistemology is not regulative epistemology. Although many philosophers in the past launched campaigns to repair our intellectual shortcomings, it would be a stretch to describe epistemology today in those terms. Today, little traffic flows from epistemology to other fields of research. Fields such as physics, biology, or computer science are paradigms of knowledge production, but they evolve with apparently no intervention from professional epistemologists. The same apparently holds for investigation carried out by laypeople. People asking questions about politics, morality, or religion don’t ordinarily appeal to the relatively esoteric products of epistemological research to guide them. And when newspapers or magazines feature stories of truth-seeking gone awry—bias in scientific research, say—journalists don’t ask epistemologists for a sound bite. Epistemology is not known as a field that trades in guidance.

2. The Drift

I’ve already noted that early modern and early twentieth-century epistemological projects aimed to guide inquiry. So what happened? As I’m concerned with it here, epistemology is careful reflection on inquiry. Professional

1 Reaching over to my bookshelf, I find several introductory books on epistemology, and each one includes a terse statement about its subject matter: “The theory of knowledge, or epistemology, is the branch of philosophy that addresses philosophical questions about knowledge and rationality. Epistemologists are primarily interested in questions about the nature of knowledge and the principles governing rational belief” (Feldman 2003a, 1). “Epistemological questions involve the concepts of knowledge, evidence, reasons for believing, justification, probability, what one ought to believe, and any other concepts that can only be understood through one or more of the above” (Fumerton 2006, 1). “Epistemology is the philosophical study of knowing and other desirable ways of believing and attempting to find the truth. . . . Most of the central questions of epistemology, then, pertain to knowledge: What is knowledge? Is knowledge possible? How do we get it?” (Zagzebski 2009, 1–2).

epistemology involves such reflection and thus qualifies as epistemology in my sense. But the field has been dominated in recent generations by methods and preoccupations that have drawn it away from the ongoing business of inquiry. The practices and problems of real-world investigators do not normally shape epistemologists’ work, though there are interesting exceptions. In general, the discipline has drifted away from inquiry in this sense: its products are not likely to direct anyone’s intellectual efforts.2

To see what I mean, just reflect on situations where we need guidance. We often confront complex, mixed bodies of evidence. How can we determine what our evidence makes it reasonable for us to believe? Epistemologists could at this point provide us with stock theories of epistemic justification. Perhaps they tell us that process reliabilism is true: a belief is justified when it is produced by a process that generates mostly true beliefs (Goldman 1979). Or perhaps theorists report that evidentialism is true: a belief is justified when it is a fitting response to our evidence (Feldman and Conee 1985). Over the last few decades, hundreds of articles have been written on reliabilism and evidentialism, to mention only two popular theories. But, all on their own, do reliabilism or evidentialism offer guidance? These theories do seem to help if we need to distinguish between cases of justified and unjustified belief, where we happen to know all of the background details about the cases. The background details would include, for instance, facts about the total evidence or the belief-forming processes that produced some beliefs. But when we need guidance, we typically need something else. Learning about the nature of justified belief won’t usually tell us how to gain or preserve justified belief when we’re faced with complex bodies of evidence and ignorance about the specifics of our situation.

But let’s be fair to the theorists. Their goal was not to guide. Instead, they aimed to describe the nature of epistemic goods or articulate reasoning for or against general epistemic principles. One possibility is that theorists need not explicitly aim to enhance inquiry in order for their efforts to accomplish precisely that. A theory that’s good for one thing can also be good for another. So why not think epistemologists’ labors already serve some regulative purpose or other?

2 I am thinking of inquiry in a broad sense to include a wide range of practices where evidence is used to answer questions. We can say that personal inquiry involves one person asking herself what to think about a topic and how to go about gaining information to form a good opinion on that topic. In a social inquiry, there is some question about what a group or community should think about some question. A particular personal or social inquiry could take as its object some question about science, ethics, politics, history, religion, or the like.

That idea is charitable but implausible. Critics of recent epistemology have often explicitly denied that standard theories and theoretical investigations improve inquiry. For instance, Mark Kaplan, in an article criticizing research on propositional knowledge, tells epistemologists “to stop and face the unpleasant reality that we simply have no use for a definition of knowledge” (1985, 363). Michael Bishop and J. D. Trout write: “It is time for epistemology to take its rightful place alongside ethics as a discipline that offers practical, real-world recommendations for living” (2005, 6). Mark Webb asks whether epistemology can be “of any use to non-philosophers” and answers thus: “Not by doing what [epistemologists] have been doing for most of the twentieth century” (2004, 51). According to Susan Haack, “much contemporary work in epistemology is hermetic and self-absorbed” and can’t help people who are seeking to inquire (2015, 3). And Stephen Stich piles on:

On the few occasions when I have taught the “analysis of knowledge” literature to undergraduates, it has been painfully clear that most of my students had a hard time taking the project seriously. . . . They could recognize the force of the increasingly arcane counterexamples that fill the literature, and they occasionally produced new counterexamples of their own. But they could not for the life of them see why anybody would want to do this. It was a source of ill-concealed amazement to these students that grown men and women would indulge in this exercise and think it important—and of still greater amazement that others would pay them to do it! This sort of discontent was all the more disquieting because deep down I agreed with my students. (1990, 3)3

Theorists have not returned fire at their critics by asserting that standard theories improve inquiry. Silence does not imply the allegations are correct. But it’s doubtful, I think, that standard answers to questions like “What is knowledge?” or “What is epistemically justified belief?” or “Is there a good response to radical skeptical arguments?” are likely to guide anyone’s investigation.

If all professional epistemologists were to suddenly hang up their boots— or if, forbid the thought, their conference hotel was destroyed by a bomb— what would happen? The world would want for new articles and books in

3 Thanks to Samuel Kampa for reminding me of this passage.

professional epistemology. But human inquiry would proceed mostly uninterrupted.

Here is my view of the matter. As the critics insist, abstract theories about inquiry don’t, on their own, help imperfect inquirers. However, we should not leap to pessimistic conclusions about the potential usefulness of recent theories. Use is the best test of an idea’s utility. I doubt theorists have put their ideas and methods to that test. They have not, in the main, tried to use their ideas to guide inquiry. Yet I think that many recent theoretical proposals can do precisely that. But not on their own. First, the proposals must be repurposed, salvaged for regulative aims, and fitted carefully within a new framework for theorizing.

3. Academic Specialization and Professional Epistemology

Before I say more about how regulative theorizing works, it will prove instructive to consider this question: why has contemporary epistemology drifted away from direct concern with inquiry? Thinking broadly about the nature of academic specialization will suggest a plausible explanation.

The field of epistemology is one branch of academic philosophy, and philosophy is itself one branch on the tree of academic disciplines. Epistemology’s place on the tree seems to presuppose that epistemologists will not guide inquiry. That’s just what we get with the organization of highly specialized research. Advances in organic chemistry will probably never help to answer questions about aeronautical engineering or Soviet political history. Academic epistemology is just one insular, specialized discipline among many.

Although epistemological research sometimes draws on ideas from the social and cognitive sciences, empirically-informed epistemologists have been a minority in the field in recent years. Knowing little or nothing about the sciences or the humanities does not impede most contemporary research, in part because knowing about inquiry elsewhere is not required. And practitioners do not seem to assume that progress in answering their questions would mandate changes in how other investigators do their jobs. Few professional epistemologists believe that their theoretical offerings— even if correct—will do much to help researchers elsewhere improve their store of knowledge or justified belief. Epistemologists have their own field to

roam and they seldom stray from it. Even less often do outsiders drop by for a visit.4

If it’s guidance for inquiry that people need, they will probably look elsewhere. The “logic” of academic specialization suggests why epistemology has drifted away from the wider world of inquiry. The evolution of academic fields depends on the making of distinctions. Over and over again, the world of knowledge has been broken into smaller pieces, like miraculously dividing loaves of bread. New distinctions create new disciplines, subdisciplines, and subsubdisciplines. The evolution of increasing differentiation and segmentation has produced professional epistemology. I return to this issue in Chapter 2, but it is enough for now to see that practitioners find within their field’s boundaries a set of questions and answers that is largely for them alone. Their questions, or perhaps their answers, are apparently not of much relevance for the conduct of inquiry anywhere else.

4. The Vienna Circle, Sputnik, and Gettier

I’ve used some ideas about the organization of academic disciplines to describe how professional epistemology drifted away from real-world inquiry. Granted, these ideas are a bit abstract. We will see the drift more easily by considering a historical story. We can recognize epistemology’s drift by noting some sweeping changes that made the field increasingly specialized through the middle decades of the twentieth century. I will tell the story in two parts: first, by describing the broad background conditions that led to the rise of “analytic” philosophy in the United States after the Second World War and, second, by looking at how one methodology became dominant in professional epistemology during the 1960s and ’70s.

The story begins with the Vienna Circle in the 1920s and ’30s. As I noted earlier, the members of the Circle used empiricism as a tool to articulate and defend the “scientific world-conception.” They declared in a manifesto that “[n]eatness and clarity are striven for, and dark distances and unfathomable depths rejected” (Neurath, Carnap, and Hahn 1979 [1929], 89). Their

4 Let me say what I don’t mean. I don’t deny that progress in academic epistemology leads to changes in how research is conducted in other philosophical subdisciplines, such as metaethics or metaphysics, where philosophers often wrestle with epistemological quandaries. I also don’t deny that occasionally epistemological research could clear up confusions in fields far from professional philosophy. Neither do I suggest that academic epistemology could not pique the curiosity of researchers in other disciplines or interested people more generally.

empiricism led them to dump “the metaphysical and theological debris of millennia” (1979 [1929], 89). Their epistemological project was intended to resolve problems in philosophy and science, but it was also part of an effort to reorder social and political life.

The reception of the Vienna Circle’s ideas on American soil occurred during an important transition in twentieth-century philosophy. During the first third of the century, American philosophy was a relatively eclectic enterprise where scholars explored broad questions about value, society, education, and metaphysics. Through the 1930s and ’40s, the scene was transformed by the importation of ideas from Europe. These ideas challenged the methodological underpinnings of American philosophy. One idea, stemming from writings by Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889–1951), was that traditional philosophers were doing something meaningless and that philosophical work properly pursued would clarify meaning through careful analysis. The ideas of the Vienna Circle moved in these currents. At first, these new ideas reached U.S. shores in the form of articles, books, and homegrown philosophers returning from European tour, such as a young Willard Van Orman Quine (1908–2000). But then important Circle members fled totalitarian Europe for the safety of American teaching posts. For instance, Rudolph Carnap (1891–1970) moved from Europe to the University of Chicago and later the University of California, Los Angeles, while Phillip Frank (1884–1966) taught physics and philosophy of science at Harvard University.

Nevertheless, the bold vision and style of ideas from the Circle, sometimes labeled “logical empiricism,” primed many American philosophers to reconceptualize the methods and problems of philosophy, even though many of them rejected logical empiricism. Looking toward the sciences, many philosophers found a new model for objectivity and value-free neutrality. Influential members of the profession increasingly regarded the hard sciences as the ideal and championed a new conception of scientific philosophy, which involved hostility toward metaphysical speculation, instead treating conceptual or linguistic analysis as the proper work of philosophers. Bruce Kuklick suggests that “[t]hese developments gave American thought worldwide honor in professorial circles, but came at great cost to the public presence of philosophy and even to its audience outside the academy. . . . In contrast to what philosophy had been . . . philosophy after World War II had narrow concerns” (2001, 199). American philosophy’s humanistic roots began to wither. As Alexander Nehamas noted, philosophy in the United

States around mid-century “no longer saw itself as bearing a direct relation to the world.” For most researchers, the field was “an essentially theoretical discipline” (1997, 212). As Quine confessed, philosophers have no “peculiar fitness for helping to get society on an even keel” (1981, 193).5

In the ’20s and ’30s, many members of the Vienna Circle had hoped their approach would renovate social and political life. So what happened in the United States? As George Reisch (2005) argues, the Circle’s ideas and ambitions were “depoliticized” in America following the Second World War. The dark paranoia of the McCarthy years meant that many socialist and left-leaning academics were scrutinized and sometimes persecuted. These were the days of loyalty oaths and hunts for communists. The director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, J. Edgar Hoover, had case files on Carnap and Frank, who were surveilled by agents in the ’50s. Although logical empiricism in America was by no means an apolitical movement, as is sometimes asserted, the Circle’s technical and methodological ideas— not its social or political ones—blossomed in the anti-communist soil. During this period, many believed commitment to one’s academic vocation ought to be free from values and politics, especially radical politics. As Reisch notes, some academics thought “the path to intellectual success and integrity in any discipline and the path to job security and freedom from political attack were one and the same” (2005, 233). Analysts did not dream to remake their world. Their ambitions were more modest: they were building a professional field where conceptual technicians could solve theoretical problems.

These conditions in professional philosophy figure into wider trends that some historians call the “new rigorism” of the post-war university. Disciplines like economics, political science, and English literature also remade their goals using putatively objective tools. Like philosophy, these disciplines turned from many of the broad, synthetic concerns and value questions that had defined education and scholarship in earlier decades (Bender and Schorske 1997). Some observers at the time described a new style of modern American intellectual who had dispensed with “wide-ranging, curious, adventurous and humane study” and instead aimed to produce “results”

5 Hans Reichenbach, an influential logical empiricist expelled from Germany by fascists before taking up a teaching post at UCLA, wrote in his 1951 book The Rise of Scientific Philosophy: “Those who ask the philosopher for guidance in life should be grateful when he sends them to the psychologist, or the social scientist; the knowledge accumulated in these empirical sciences promises much better answers than are collected in the writings of the philosophers” (quoted in Reisch 2005, 355).

(Reisch 2005, 349). The forces shaping mid-century academic philosophy came from both within and without.6

And so it was that professional epistemology began to find its life and purposes in the 1960s. The whole story here is complex and involves a large cast of characters and theoretical projects, ranging from Chisholm’s work in the ’50s on foundationalism to C. I. Lewis’s work on the “given” (the sensory qualities we are immediately aware of in experience). But we can begin to see what happened in the field by zooming in on one particular episode.

It begins at a public university in Detroit, Michigan during the early 1960s, a few years before the city would descend into economic failure, “white flight,” and postindustrial decay. John F. Kennedy was still president and the Philosophy Department at Wayne State University had recently hired a group of young philosophers. Some of these philosophers had turned down job offers from Ivy League universities. They chose instead to teach in the cinder-block buildings on Wayne State’s urban campus.

These were peculiar days in the American academy. The Soviet launch of Sputnik 1 into orbit in October 1957 precipitated a hiring bonanza across many fields. In response to fears that the United States was falling behind the Soviet Union in education, President Eisenhower’s National Defense Education Act of 1958 flooded the country’s universities and colleges with resources as never before. Historians have noted the dramatic changes to fields like physics (Kaiser 2006), but academic philosophy was also transformed. There were more teaching posts for philosophers than there were new PhDs to fill them. Some young philosophers had their pick of the available jobs.7

One faculty member in the Wayne State department, Keith Lehrer, had accepted a job offer from Brown University and then wriggled out of his contract to go to Detroit; another, Alvin Plantinga, chose Wayne over Yale. They went to Detroit on the promise of an intense intellectual community, persuaded by the department chair, George Nakhnikian. They weren’t

6 See Reisch (2005) and Isaac (2012) for more on the rise of scientific philosophy in mid-century America.

7 This situation didn’t catch professional philosophers by surprise. In the wake of Sputnik 1, a committee of the American Philosophical Association, chaired by none other than Roderick Chisholm, produced a report on the state of graduate education in American philosophy. The report notes that “a shortage of qualified philosophy teachers will probably become serious before 1965” (Chisholm et al. 1958–1959, 155, footnote 1). To increase supply to meet demand, the report recommends that philosophers “should investigate the possibility of making more extensive use of our total resources of teaching manpower, for there are certain groups we now tend to overlook. It may be, for example, that we do not now give sufficient encouragement to women, or to certain racial groups, or to people who have been working outside of the academic world” (1958–1959, 149).