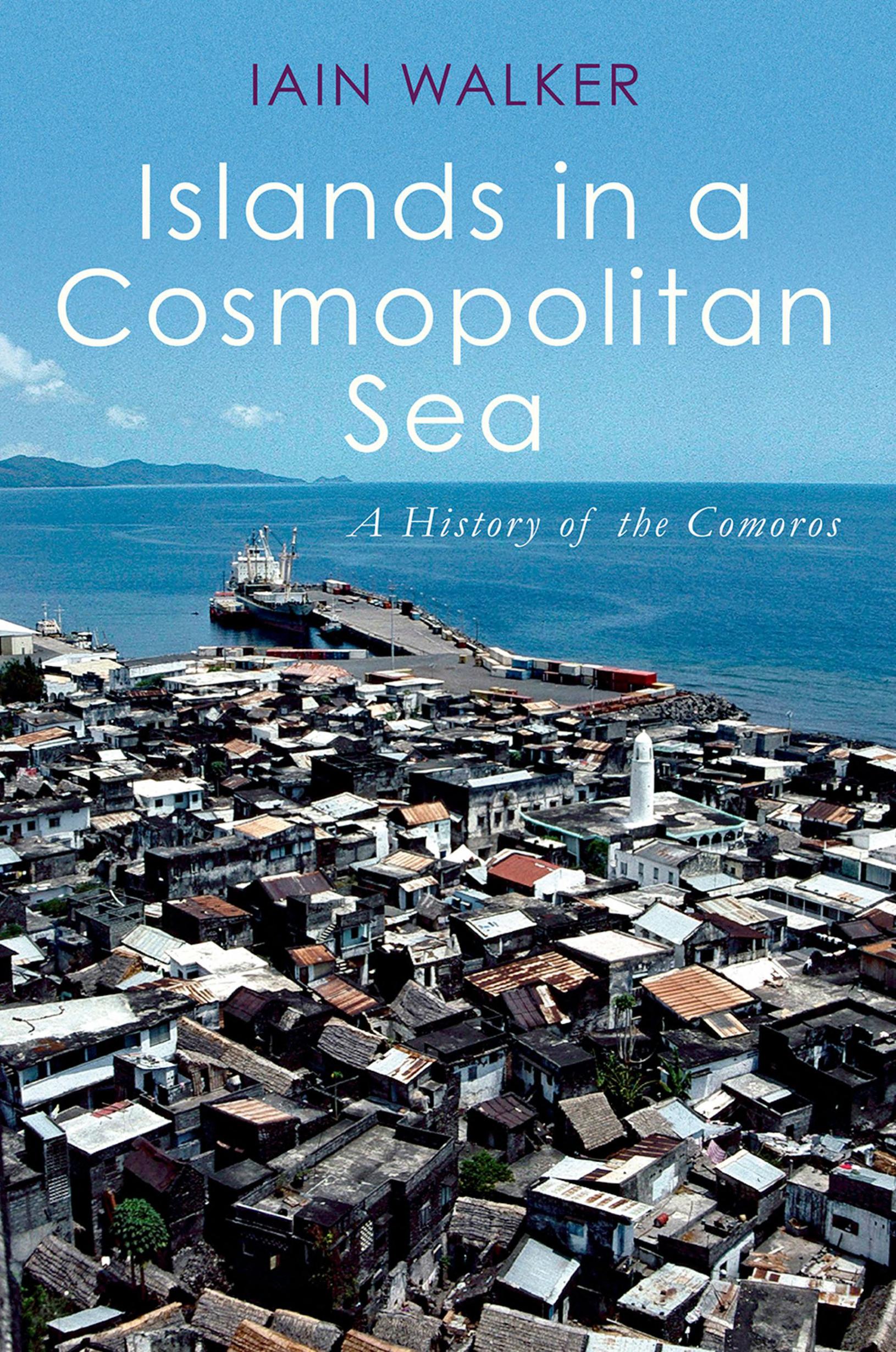

IAIN WALKER

Islands in a Cosmopolitan Sea

A History of the Comoros

3

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America

© Iain Walker, 2019

First published in the United Kingdom in 2019 by C. Hurst & Co. (Publishers) Ltd

All rights reserved. No part ofPublication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer

A copy of this book’s Cataloging-in-Publication Data is on file with the Library of Congress.

ISBN 9780190071301

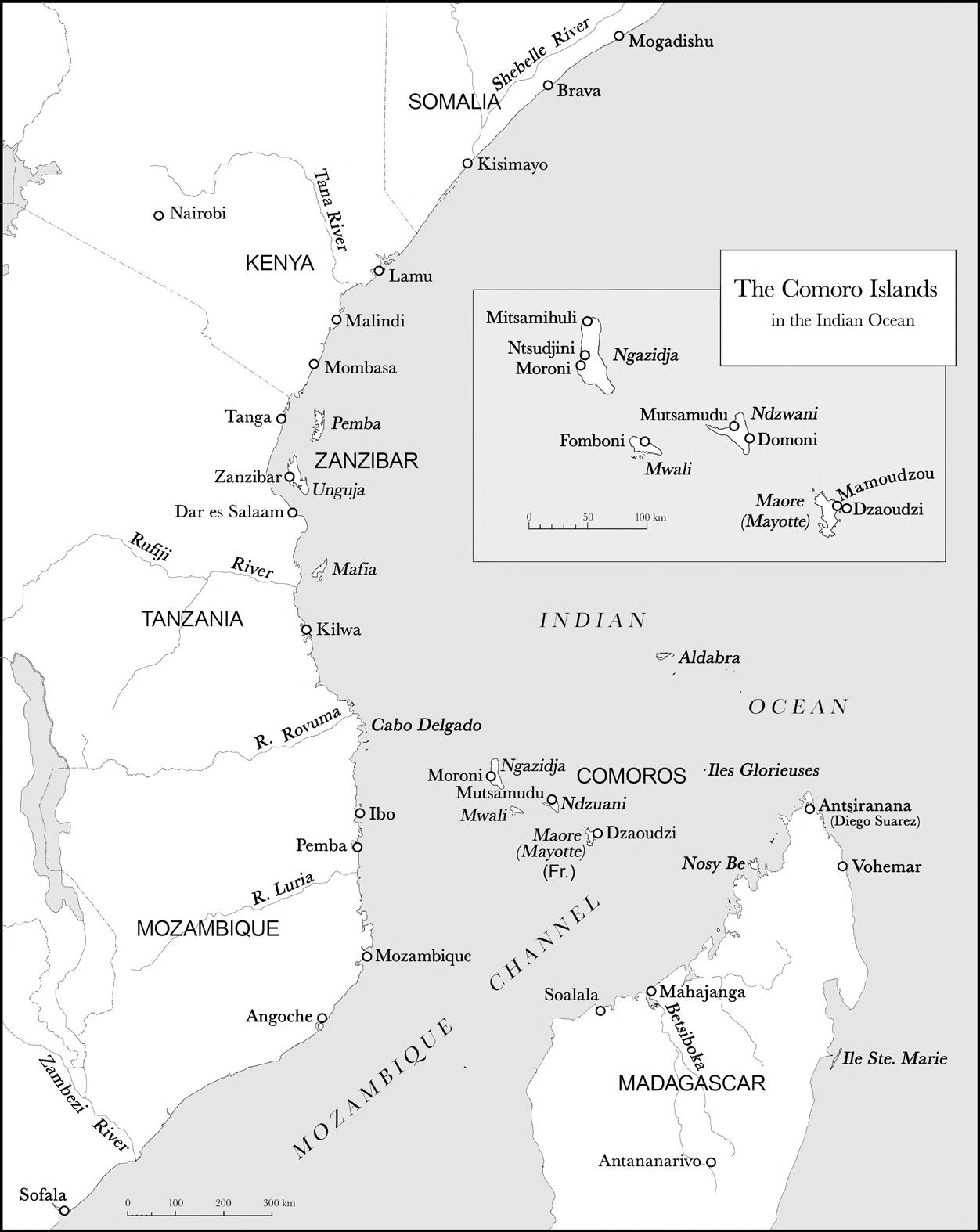

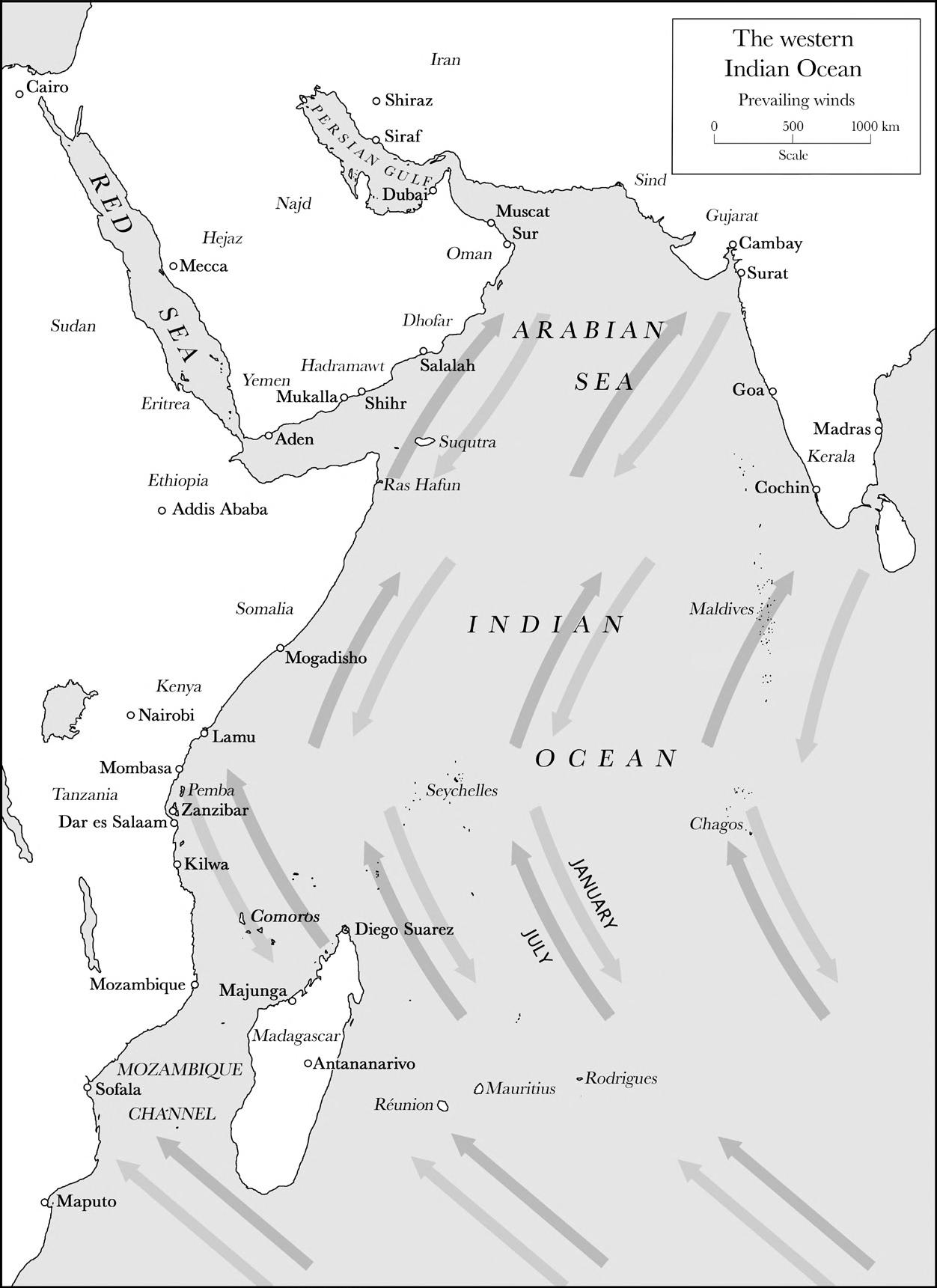

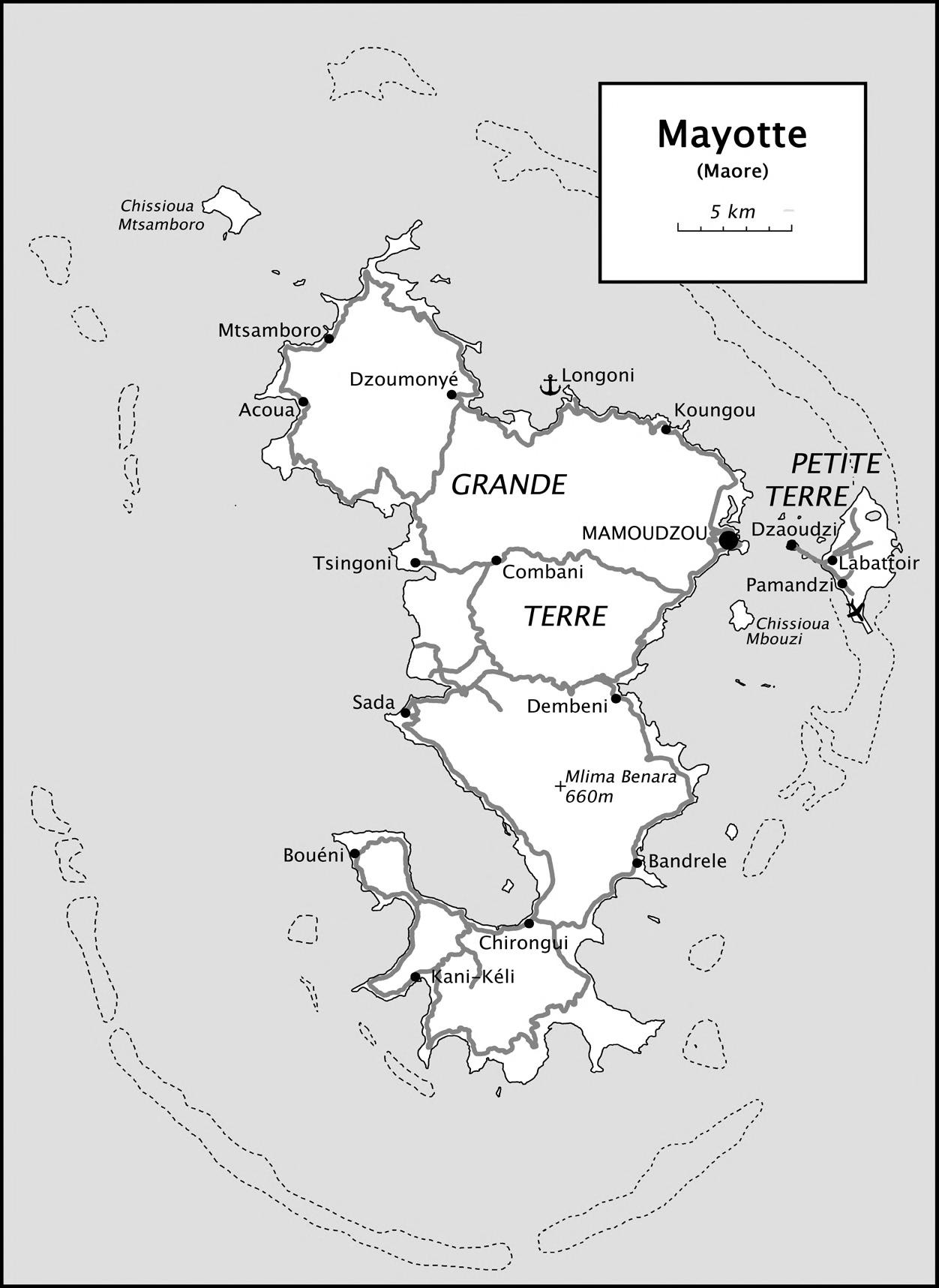

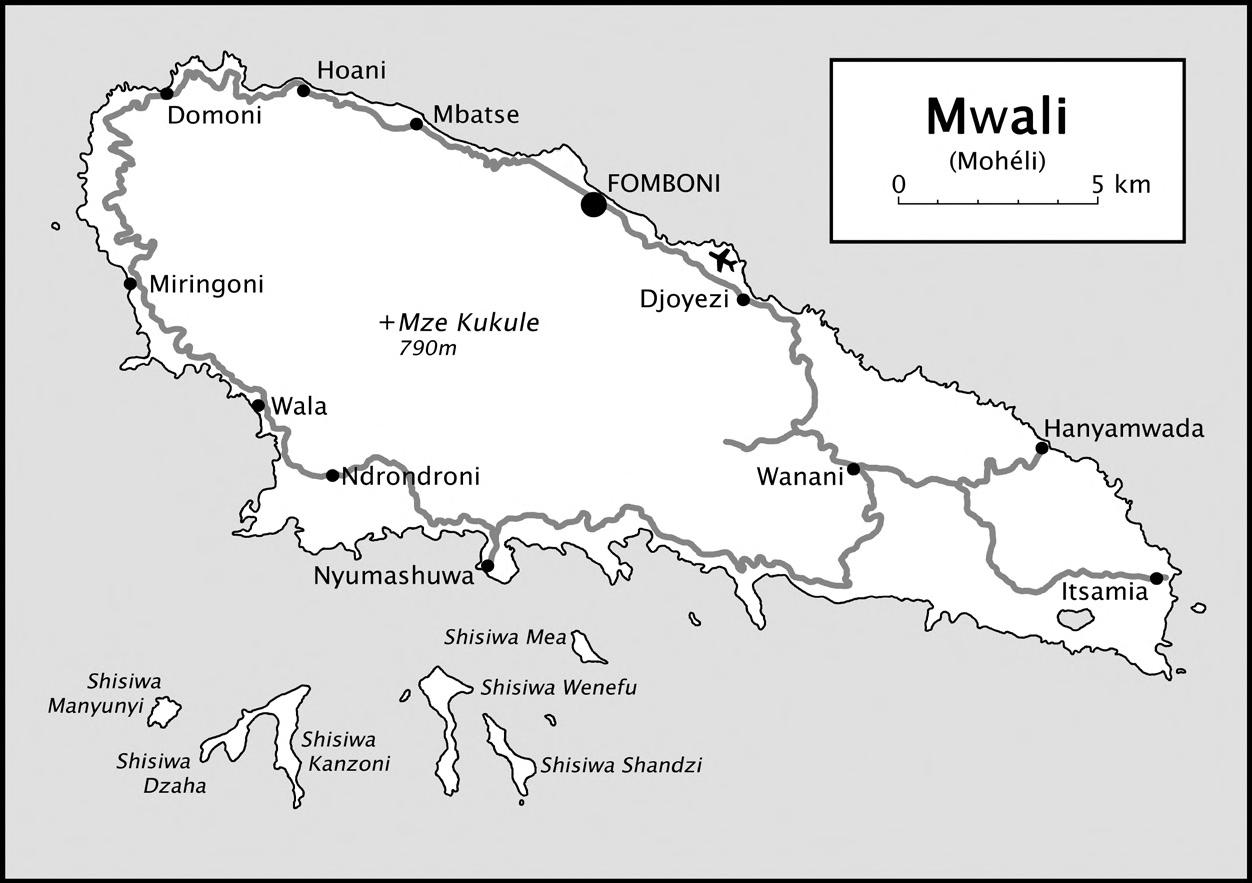

Map of the Comoros

Map of the Western Indian Ocean

Map of Mayotte

Map of Ngazidja

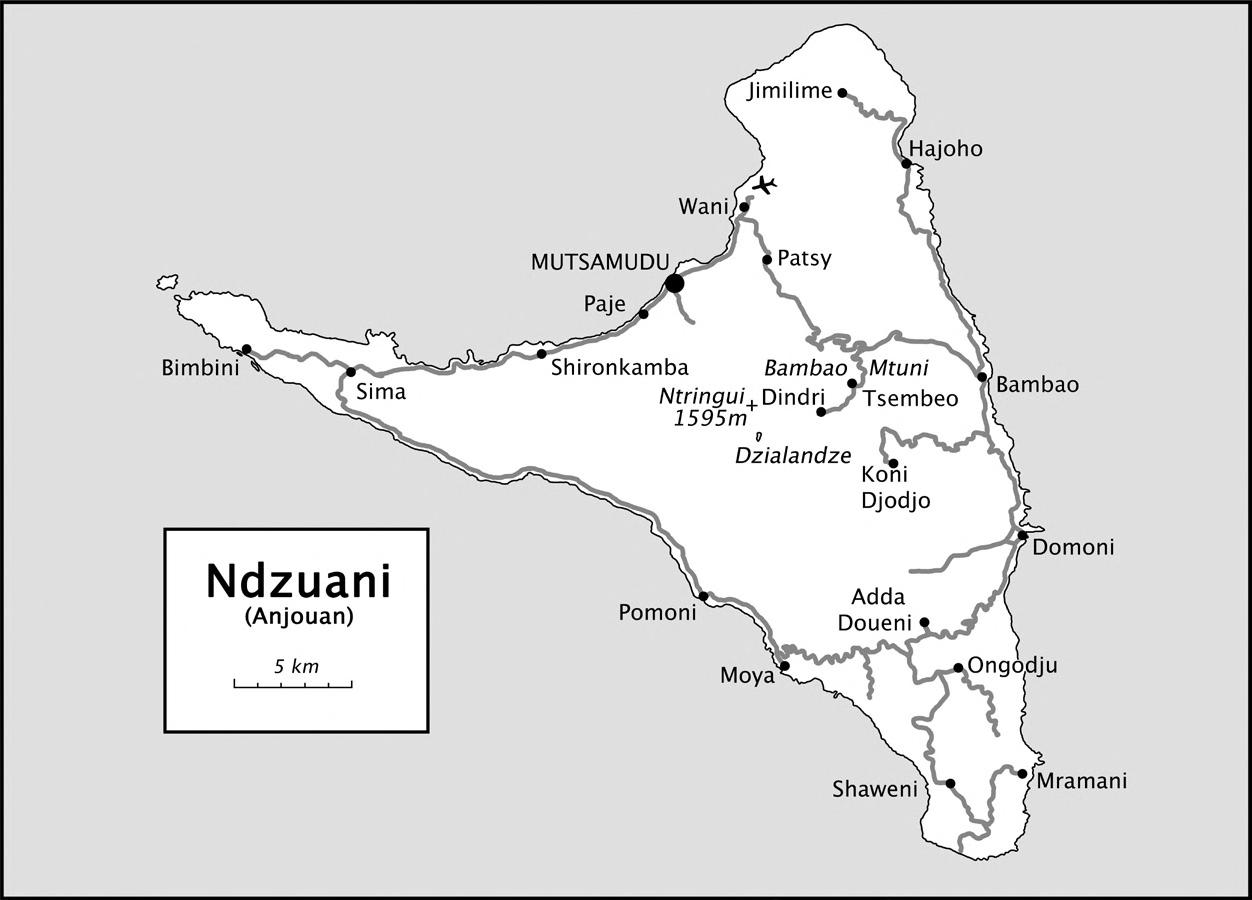

Map of Ndzuani

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

1. The earliest known sketch of Ngazidja, from João de Castro’s Roteiro de Lisboa a Goa, an account of his voyage to India in 1538.

João de Andrade Corvo, ed., Roteiro de Lisboa a Goa por D. João de Castro, Lisbon, Academia Real das Sciencias, 1882. See another version online on the Biblioteca Nacional de Portugal website, http://purl. pt/27123/5/P164.html.

2. An engraving of the island of Mayotte, portraying the visit of the Dutch admiral Jacob Van Heemskerk in 1601.

Willem van West-Zanen, Derde voornaemste Zee-getogt (Der verbondene vrye Nederlanderen) na de Oost-Indien: gedaan met de Achinsche en Moluksche vloten, onder de Ammiralen Iacob Heemskerk, en Wolfert Harmansz, In den Jare 1601, 1602, 1603, Amsterdam, H. Soete-Boom, 1648.

3. A 1705 map of the Comoros and the nearby mainland coast, by Pieter Mortier. Ngazidja is disproportionately large, its exaggerated size reflecting navigators’ wariness of the island.

Pierre Mortier, Carte Particuliere des Costes de l’Afrique Depuis C. Del Gado Jusques Rio Mocambo, et les Isles aux Environs: Levée par Ordre Expres des Roys de Portugal sous qui on en a Fait la Decouverte, Amsterdam, 1705.

4. Moussamoudo (Rough sketch of Johanna, half the town—H.B.M. Consulate & Anchorage) May 1875, J.E. The captions read, from left to right: Town walls; Old ruined Arab fort; Anchorage; H.B.M.’s Consulate with yard & landing place; Town walls with ruined fort; Mssrs Dunlop Mees & Co of Rotterdam (Agency); River ‘Ziancunde’; Saddle Island; Sultan’s House; Mosque.

Courtesy of the National Archives, London, UK: National Archives, Records of the Admiralty, ADM 127/36: ‘Admiralty: East Indies Station: Correspondence. Islands in the Indian Ocean; and the East Coast of Africa. Zanzibar, Madagascar, Comoro Islands and Mozambique. 1883-1888.’

5. The first issue of the government-owned national newspaper, then called Al-Watwany, with the portrait of President Ahmed Abdallah on the front page.

Courtesy of Al Watwan.

6. A silver 5000-franc coin, part of a prestige collector’s set of three coins bearing the portrait of Said Mohamed Cheikh, issued as a revenue-raising exercise in 1976 by Ali Soilihi.

7. Sultan Said Ali ben Said Omar of Bambao, Ngazidja, surrounded by the notables of the island.

Courtesy of the Centre National de Documentation et de Recherche Scientifique, Moroni, Comoros.

8. Sultan Said Omar el Masela of Ndzuani with, to his right, Pierre Papinaud, governor of Mayotte from 1888 to 1890.

9. A contemporary pro-Comorian roadside sign in Moroni.

Photo taken by the author.

10. The former governor’s residence, Dzaoudzi, Mayotte.

Photo taken by the author.

11. A wooden-framed mud-plaster house, Mwali.

Photo taken by the author.

12. Aerial view of the town and port of Itsandramdjini.

Photo taken by the author.

13. Bull-baiting during an ãda wedding at Fumbuni, Ngazidja.

Photo taken by the author.

14. The zifafa, a procession in the ãda wedding on Ngazidja, during which the groom is escorted to his future residence.

Photo taken by the author.

GLOSSARY OF TERMS APPEARING IN THE TEXT

ãda na mila the body of ritual customary practice; unless otherwise specified, ãda itself usually refers to the ritual marriage (Ng); see below

ajojo Comorians, and specifically usually Wangazidja (Mg)

banga hut where young boys sleep after puberty (My, Nz; cf. vala)

bangwe public square in village (Ng, Mw; cf. mpangahari, trengwe)

bedja ruler, pre- or early Islamic period (Ng)

bidaa “innovation” in Islam

fani ruler, pre- or early Islamic period (Mw, Nz)

galawa outrigger canoe

gungu ritual punishment that involves blackening an individual with soot and parading him or (more rarely) her through the streets of the village to be publicly shamed (Ng)

hinya matrilineage, clan (Ng)

itreya village of slave origin (Ng)

kashikazi wet season, summer

kusi dry season, winter

kwasa kwasa speedboat used to carry migrants to Mayotte, generally illegally

mafe local rulers, pre-Islamic period

maferembwe local rulers, pre-Islamic period (Ng)

makabaila aristocracy of Arab descent (My, Nz)

manyahuli land collectively owned by a hinya (Mw, Ng)

mdji village (see also ritual terminology below)

mfaume “king”, used prior to the adoption of the title of sultan

mila na ntsi body of customary law governing, amongst other things, ãda na mila (Ng, see pp. 34, 117–8, 176–8)

GLOSSARY OF TERMS APPEARING IN THE TEXT

mpangahari public square in village (Nz; cf. bangwe, trengwe)

ntibe meat dish eaten at ãda meals; Sultan Ntibe, the paramount sultan on Ngazidja

ntsambu seed of a cycad (Cycas thouarsii) typically eaten on Ngazidja

ntsi land, kingdom

sabena Comorian repatriated from Mahajanga in 1977 (cf. zanatany)

silamu Comorian in Madagascar, Malagasy of Comorian origin (Mg)

trengwe public square in village (My; cf. bangwe, mpangahari)

ulapva customary banishment of an individual or a mdji (Ng)

ustaarabu the state of being civilised; cf. washendzi

vala hut where young boys sleep after puberty (Ng, Mw; cf. banga)

wamatsaha “Bushmen”, the original inhabitants of Ndzuani

washendzi uncivilised people, often used to refer pejoratively to African mainlanders

zanatany Comorian born in Madagascar (Mg, but used on all islands, cf. sabena)

ziyara pilgrimage to a local shrine; on Mayotte, a site of spiritual significance

Islam and related terms (pp. 45–7 and 115–8)

cadi Islamic judge

fundi teacher, of any kind, but usually understood as a religious teacher

hatwib preacher in the mosque, often a hereditary title

maulida reading celebrating the life of the Prophet; Maulid is the Prophet’s birthday

mwalimu learned man, a healer, often drawing on both religious and nonIslamic knowledge (see pp. 31–32)

qasida Islamic poem, often sung

sharifu descendant of the Prophet Muhammed through his daughter Fatima

Political terminology, regime of Ali Soilihi (pp. 155–7)

bavu administrative division

liwali administrator of a bavu

Commando Moissi Soilihi’s elite military squad

Mongozi leader, guide

mouhafidh administrator of a wilaya

mudir administrator of a mudiriya

mudiriya administrative division

wilaya administrative division

Clothing (pp. 217–8)

bushuti, djoho, djuba, dragla gowns worn by men and which indicate a particular status, customary or religious kiemba, kofia headgear, the former worn usually only by the groom at ãda weddings, the latter worn daily by all men

mharuma shawl worn by an elder as a sign of status nkandu gown, usually white, worn daily by men bwibwi black garment worn by women, similar to the Arab abaya

leso, saluva colourful garments worn by women daily sahare, subaya more formal dresses worn by women, usually in ritual contexts

shiromani distinctive red and white patterned cloth typically worn by women on Ndzuani

Sufism (pp. 120–1)

daira circle; a group of sufi adepts

dhikr repetitive chanting in a sufi ritual

twarika sufi brotherhood

zawiyya sufi meeting place

Dances (pp. 218–9)

bomu, lele mama, wadaha, twarab women’s dances, usually at marriages biyaya, djaliko, sambe, shigoma, twarab men’s dances, usually at marriages

Age system and ritual terminology (pp. 35, 117–20, 211–5; Ngazidja unless otherwise specified)

Darweshi group opposed to the expenses of the ãda on religious grounds

GLOSSARY OF TERMS APPEARING IN THE TEXT

djeleo ãda marriage event at which food is distibuted to be cooked

guzi an age grade occupied someone either close to or late in performing his ãda harusi wedding; hence bwana harusi, the groom, and bibi harusi, the bride (all islands)

hirimu age grade or set manzaraka customary wedding (My)

madjeliss ãda marriage event of Islamic inspiration mdji literally village, but also a group of men in the age system

mndru mndzima man who has performed his ãda; an elder (literally “complete man”, pl. wandruwadzima) wafomanamdji an age grade of senior young men, yet to perform their ãda (literally, “kings of the children of the town”) wanamdji collectively, boys and men who have not performed their ãda (literally, “children of the town”) wandruwadzima see mndru mndzima

ntswa shenda nine days following the zifafa during which the groom is confined to the house shungu meal in age system, often linked to marriage (all islands other than Ngazidja)

zifafa ãda marriage event during which the groom is led to the nuptial house

Abbreviations, referring to island or language: Ng, Ngazidja; Mw, Mwali; Nz, Ndzuani; My, Mayotte; Mg, Malagasy

PREFACE

I sometimes try to cast my mind back, to revisit my impressions of the Comoros as I first saw them, some thirty-five years ago now, an enigmatic group of islands lying between Madagascar and Zanzibar that called out for me to stop and have a look. The islands were slightly mysterious, quite off the beaten track, absent from the anglophone view of the world, and prior to my visit I don’t recall meeting anyone who had even heard of them. I do remember that in 1985 the islands were both more French and more Islamic than they are today. The only cars seemed to be the ubiquitous Renault 4 (the ‘4L’), which, for a foreigner, was quintessentially French; the men, almost without exception, wore the kofia (embroidered skullcap) and nkandu (gown) that are today only really worn on Fridays, while the women were draped in leso, and rare were those who did not cover their hair. There was an exotic fragrance to the place—I only managed to visit Ngazidja—whether it was ylang ylang that I could smell or just exotic flowers generally, I don’t recall.

There were no other tourists as far as I could tell: I appeared to be the only guest in the once glamorous Hotel Karthala, although given the rundown state of the establishment, that was not particularly surprising (the water from the shower flowed across the floor, under my bed and out of the door to drip over the edge of the balcony). But the islands were charming, the people too, and the one beach I managed to find was, prior to the construction of Bob Denard’s Galawa Hotel, palm-fringed and quite deserted. And then there were the exotic volcanic landforms: eroded craters and lava flows, all giving the island a slightly surreal aspect. As a budding young anthropologist—I had just finished fieldwork for my master’s thesis in Mauritius—I asked a few appropriate questions and found out about an extravagant big wedding and a matrilineal kinship system which, a decade later, would tempt me back to do my PhD. Most of all, though, I had the feeling of being outside the normal flow

of events, isolated from the rest of the world, to which the island seemed to be only very tenuously connected by a small handful of weekly flights.

Today the islands have changed somewhat—most noticeably both the 4Ls and the Islamic attire have largely gone and the Hotel Karthala, alas, has also gone (it is now the faculty of arts of the university). But, surprisingly, much of the rest remains: the people, who have always been welcoming (and very tolerant of the peculiar questions that anthropologists ask); the exotic landscapes and the perfumes; and, of course, the weddings, ever more extravagant. My own perspectives on the islands have, of course, changed dramatically, and, with a view to introducing what follows, one of the greatest shifts is in my perception of the islanders’ relationships with the ‘outside’ world: isolated the islands most certainly were not. Comorians are great travellers, and are adept at negotiating their relationships with foreigners, both at home and away. This should have been immediately apparent on my first visit: unlike parts of Madagascar, where children would run after me crying Vazaha! vazaha! (‘European’) and adults would try to sell me something, in the Comoros, and despite the apparent absence of visitors, no one gave me a second glance: a reflection, I think, of the familiarity with the world that Comorians enjoy. I hope in what follows I have been able to convey a sense of both the uniqueness and the worldliness of the islands (even if the latter is occasionally touched by some naivety), and redress some of the more widespread misconceptions about the country (particularly its baffling reputation for violence: it is among the most peaceful places on earth). Much history has been gleaned from books and archives but I have, of course, also learned a great deal from my Comorian friends and colleagues, historians of their own country and observers and guardians of traditions, and although I am grateful to all of them, I should particularly like to thank Damir Ben Ali, whose door I regularly darken with my notebook clutched in my hand. Henry Wright was kind enough to read a draft version of Chapter Two and provide valuable comments, and Edward Alpers did likewise for Chapter Three. I am grateful to both as well as to two anonymous reviewers of the final draft. I would particularly like to thank Robert Aldrich, who read a full first draft of the entire manuscript and whose critiques, and criticisms, were invaluable as I revised it. I hope it is a better book for his remarks; if not, the fault is entirely mine.

Language, names and orthography

I refer to the islands of the independent state by their Comorian names, Ngazidja, Mwali and Ndzuani, although I maintain the original names or

spellings in quotations. Their French names—Grande Comore, Mohéli and Anjouan respectively—are, of course, still widely used in the literature but the use of the local names has several advantages. First, it ‘decolonises’ the language used, particularly desirable given that in two cases, Ndzuani and Mwali, the French names are simply French attempts to represent the Comorian name. Secondly, it removes the ambiguity between ‘Comorian’ as an adjective for all islanders and ‘Comorian’ as referring only to people from Ngazidja; and thirdly, it allows me to use, with a degree of consistency, the various derivatives of the names for the people and the language: the prefixes m-, wa- and shirefer, respectively, to the singular and plural of the inhabitants and to the language. Thus one Mngazidja is only one of many Wangazidja who speak Shingazidja. However, I call the fourth island (Maore in Comorian) Mayotte, since this is the official name of the French department that it now is, and the constant use of the two names in parallel would be tedious; likewise, I use the spelling Maorais (which to the foreigner sounds the same as the Comorian word Mmaore) for the people, singular or plural, although I call the language Shimaore. This should not be read as a political statement but simply a stylistic convention that follows accepted current practice in the various islands.

As for place names, in the independent islands I use currently accepted Comorian orthography, even if it is not yet widely used (visitors to the islands looking for Washili should be prepared to end up in Oichili) while for Mayotte I use the sometimes curiously hybrid orthography used by the Institut Geographique National: thus Dzoumonyé rather than the old French Dzoumogné or the contemporary Dzumonye. Readers should be alert to the fact that there are a number of places across the islands that have the same name. Bambao, the sultanate on Ngazidja, is a different place from either of the two Bambaos on Ndzuani; likewise Domoni on Mwali and Domoni on Ndzuani; and so on. Finally, with the exception of a few families of French or Arab origin, Comorians do not have family names: Fatima, daughter of Ahmed, son of Mohammed, is Fatima Ahmed to her friends, but Fatima Ahmed Mohammed to distinguish herself from Fatima Ahmed Soilihi. I occasionally use ‘bin’ (‘son of’) or ‘binti’ (‘daughter of’) where this is a common part of the name in general usage. Note that, for the sake of readability, where I use Comorian words I do not generally distinguish between singular and plural forms; finally, unless otherwise indicated, any translations from original texts in languages other than English are my own.