CONTENTS

Preface ix

Acknowledgments xiii

1. What Are the Foundations of an Integrated Approach to Teaching and Learning? • 1

What Is Music Technology? • 2

What Is Cross-Curricular? • 4

What Is Arts Integration? • 6

What Is Collaboration? • 8

What Should STEM with Arts Integration Be? • 9

What Is STEM’s Connection to STEAM? • 10

How Can We Integrate the Arts with STEM? • 14

2. How Should Learning through STEM and Music Be Aligned? • 16

Introduction: The Rules of the Pool • 16

Intentional Integration • 18

Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS) • 19

International Society for Technology in Education Standards (ISTE) • 19

Computer Science Teachers Association (CSTA) and K–12 Computer Science

Framework • 20

Mathematics Standards • 20

Engineering Standards • 21

National Core Arts Standards (NCAS) • 22

Connections between Standards and Practices • 23

Building a Shelf • 24

Aligning the Cognitive Demand Level • 25

3. How Should Learning through STEM and Music Be Assessed? • 28

The Four Main Components of an Assessment • 28

Assessment vs. Evaluation • 30

Addressed vs. Assessed Standards • 30

Compliance vs. Assessing • 30

Objectivity vs. Subjectivity in Assessments • 30

Alignment and Assessment Examples • 31

Bold and Italic Typeface in Summative Assessments • 33

Student-Centered Assessments • 33

4. How Can I Integrate STEM with Music? • 35

Lesson Title—Wearable Circuits for Piano Performance: Sustain Pedal • 35 Duration • 35

Lesson Description • 36

vi

Listing Integration of Contents • 37

Cognitive Demand Using Bloom’s Taxonomy • 37

Gardner’s Multiple Intelligences • 38

21st-Century Skills • 38

Content Standards and Arts Standards: Assessed vs. Addressed • 39

Key Vocabulary • 40

Arts Concepts Based on National Core Arts Standards • 40

Materials • 41

Essential Questions • 41

Lesson Sequence and Corresponding Assessments • 42

Summary Activity • 48

Extension Activity(-ies) • 48

Adaptations for Grade-Level Bands (K–2, 3–5, 6–8, 9–12) • 49

Lesson Cross-Compatibility and Customization • 50

5. Instructional Plans: Grades K–2 • 51

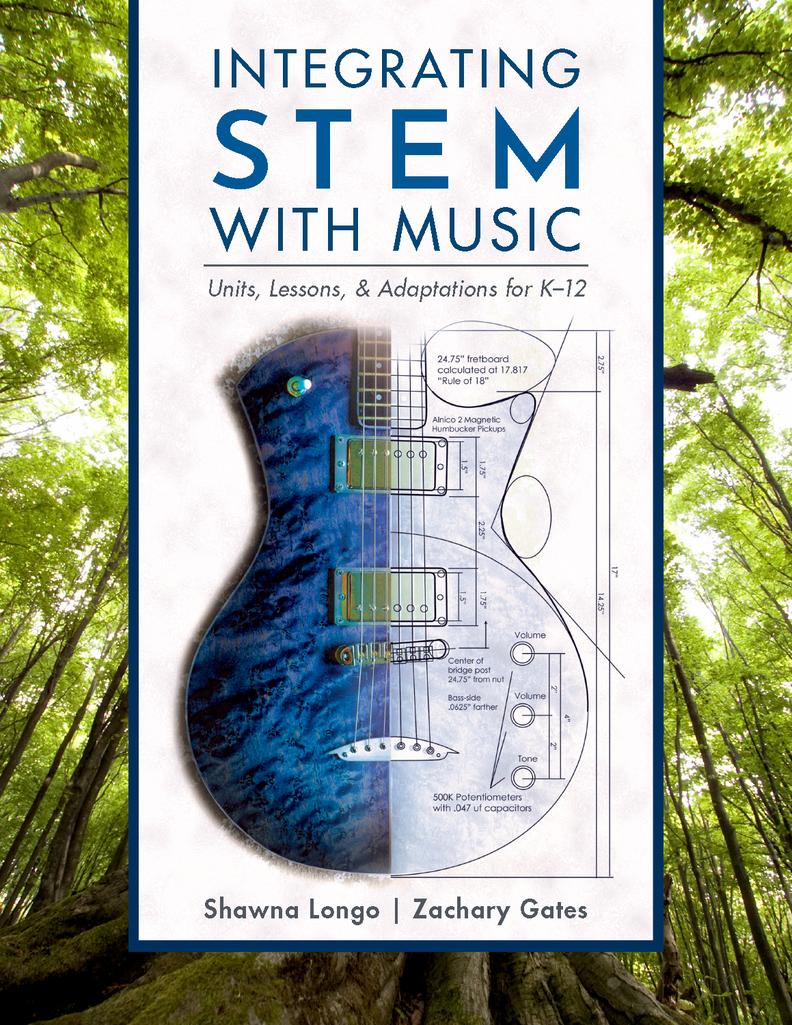

Project #1: Shapes of Electric Guitars • 51

a. Students will explore the style of Pablo Picasso’s guitar sculptures and other images showing various electric guitar shapes. Students will design and create an electric guitar using selected shapes, cardboard, and copper tape. Students will provide a musical demonstration using Makey Makey and Scratch.

Project #2: Sound Amplification and Speaker Building • 59

a. Students will learn about rudimentary acoustics, explore physical acoustic amplification and isolation, and make mobile device/speaker amplifiers using simple materials. Students will then explore how electric signals can carry audio, and how we can hear the audio by converting the sound with paper plates and magnets.

Project #3: Measuring Length and Pitch • 71

a. Students will explore the length of Boomwhackers as they relate to pitch. Students will compare the lengths of Boomwhacker tubes and place them in order by ascending pitch and then descending pitch. Students will create a simple 4-measure melody using iconic and standard notation by comparing and ordering Boomwhacker tubes.

6. Instructional Plans: Grades 3–5 • 81

Project #1: Invent an Instrument Using Recycled Materials • 81

a. Students will explore the three R’s (reduce, reuse, recycle) and the four families of instruments. Students will design and create two instruments, one percussion and one non-percussion, using geometric components and recycled materials. Students will create a written and recorded (video) tutorial for creating their two instruments.

Project #2: Composing Music Using Light: Musical Automata • 92

a. Students will configure an automatic music-making machine incorporating motorized discs, as well as light and motion sensing to compose their own song.

b. Students will conceptualize and interface with music in a non-linear way. They will build a rudimentary iteration of what’s known today as an electronic sequencer, a cornerstone of electronic music making today.

Project #3: Performing Music Using Light: Theremins and Oscillators • 102

a. Students will use concepts such as voltage, resistance, and oscillation to create their own electronic musical instruments that change pitch depending on exposure to light. Students will then perform songs with their own light theremins.

7. Instructional Plans: Grades 6–8 • 111

Project #1: Building a Fretboard • 111

a. Students will use the “Rule of Eighteenth” to calculate the location of the frets on a guitar (full size, 3/4-size, and/or 1/2-size). Students will then create a guitar fretboard using various materials.

Project #2: Piezoelectricity Experiments • 122

a. Students will learn how kinetic energy can be transferred to electricity using cheap quartz-based piezo sensors. They will be able to hook up their own sensors to capture various sounds around their environment. This will then lead to a “found-sound” music experiment where students can also make their own paper speaker.

Project #3: Composing Music Using Coding • 132

a. Students will make connections between coding and traditional music composition. Students will learn the basic function of Little Sound Dj (LSDj) software and a Gameboy emulator. Students will learn to compose a piece of music that uses all channels (PU1, PU2, Wave, Noise) and various instrument sounds. Students will further develop skills using texture, melody, harmony, percussion, dynamics, pitch, and rhythm in composing music.

Project #4: Performing Music Using Coding • 145

a. Students will make connections between coding and music performance. They will learn to code in sounds (pitch), rhythm, and movement using Scratch Desktop. Students will compose a piece of music using their Scratch code and perform it using a Makey Makey kit.

8. Instructional Plans: Grades 9–12 • 158

Project #1: Audio Engineering: Ratios in Recording • 158

a. Students will apply previous knowledge of mathematics to assist in the work typically involved with recording engineering. Applied mathematics will assist in mic positioning, monitor positioning, equalization, compressor settings, as well as spectral analysis for the purposes of creating and improving the quality of recorded and sampled audio.

Project #2: Designing a Chromatic PVC Instrument • 167

a. Students will design a one-octave chromatic instrument using mathematical calculations and representations to create initial expressive statements and explain the relationships among the frequency, wavelength, and speed of waves traveling in the PVC pipes.

Project #3: Controlled Voltage: Composing, Performing, and Improvising with Subtractive Electronic Synthesis • 178

a. Students will use electronic synthesizers in tandem with an electronic sequencer to simultaneously present a blended musical presentation of composition, performance, and improvisation.

Project #4: Field Study: Sound Pollution and Its Effects on Local Bird Ecology • 188

a. Students will learn about local ecology, noise pollution, and ornithology, as well as how to take melodic dictation. Students will then use these ideas and skills to conduct field research so as to ascertain noise pollution level and the effect it has on local bird populations.

Glossary • 199

Bibliography • 203

Index • 205

Creativity largely consists of rearranging what we know in order to find out what we don’t know. It is alchemical in a way, achieving transformation through canny and uncanny combination. Finding these combinations and connections speaks to one of the main objectives of humanity, which is the act of discovery. In creativity and science, microtonality and microgravity, lies the human pursuit of discovery. In writing this book, we discover our passion within a format and mode that we believe you will find speaks to that very purpose of discovery. Sharing knowledge and empowering students has been our goal and it is our hope that through this book, the alchemy of integrating Music with STEM can be more accessible to anyone who may find themselves perusing these pages.

Finding Our Passion and Purpose

Shawna Longo:

I always felt strongly that the more connections we as teachers make for our students within and among contents, the deeper their learning becomes. Connections make learning come to life and become more relevant. I can remember sitting in more than one high school social studies class where the blackboards ran floor-to-ceiling across the wall of the classroom. Class time would be spent copying notes that covered the entirety of these boards, and then a test would ensue. The only connection to the material experienced was in the pain I felt in my hand from copying notes for days on end.There were too many missed opportunities to make those history lessons come to life. Part of what drives me, gives me purpose, and fuels my passion is to inspire other teachers to know how important connections are for students. Without creating connections, the concepts and skills we teach are meaningless and won’t “stick” in students’ minds.

People who know me typically say that I am a hard worker and very passionate about what I do. I enjoy work—honestly, it doesn’t feel like work to me. It’s a part of who I am. But the road for me wasn’t paved as a straight line. I had many detours along the way, most of which I could have never predicted and which could have derailed me. I learned that that’s not who I am. I’m more of a “I’ll find a way to make lemonade out of any lemons that are thrown my way!” kind of person. Regardless of the detours, I had to shift and recalculate on numerous occasions to find new paths to keep me moving toward the same goals. I also believe that no matter the situation, good or bad, we can choose to learn something and improve ourselves. You need to be ready to lift yourself up and improve yourself.

Experiences can teach us what to do, and they can also teach us what not to do. The note-taking experiences that I had throughout my school life taught me what not to do and started me on this journey to make more connections for students through integration and creating engaging experiences. As we make connections for students, it is

important to also help them view and understand the world outside of where they live, while making content come to life!

Zachary Gates:

If luck does exist, then I’d say that I’ve been bestowed quite a lot of it. When I attempt to look at positive modern education in practice from a bird’s-eye view, I see a strong push toward relevance to the students’ lives represented in the wrappers the material is delivered in. A lesson may involve an internet meme, a teacher may mention social media, and in the music classroom, repertoire can take into account what is playing on the radio. While attention-catching and partly valuable because of that trait, how deep or meaningful is that experience if not followed up with actual content and facilitation of thinking that is equally as relevant? Growing up, due to a learning disability and other reasons, my attention was pretty difficult to catch in school. In many instances, it led to a school system wondering if I belonged in special education classes or accelerated classes. In my opinion, I feel I was personally lucky that they chose the latter, and that I also happened to especially excel in music class, the only class I excelled in, really. With my feeling of accomplishment feeding my actual accomplishment, I knew that a life pursuing music in any form would keep my attention, make me feel accomplished, and feed my soul.

If I had to say that there is one thing that has shaped me the most from within, it would be my penchant for exploring. Not wanting to stay in one place and bouncing from thing to thing was my natural state as a kid, but I made the choice to actually do that within music. My collectively creative and tech-savvy parents encouraged my very early case of Gear Acquiring Syndrome, allowing me to buy guitars, amps, loop pedals, and even a synthesizer before I actually knew what it was. To me, I was just exploring. Looking back, I see that I was connecting. When I bought a guitar, I didn’t just want to play it, but I wanted to go inside and solder broken connections and assemble custom electric guitars. I didn’t want to just play a synthesizer, but to know scientifically how it played, and to be able to record my musical efforts in a Digital Audio Workstation. I didn’t want to just record music and figure out how to incorporate MIDI effects, but actually use MIDI and piezo-electric sensors to help create interactive sound-art installations. For me, making the connections and knowing the inside of the instrument helped with the playing of that instrument.

If luck exists, I’m lucky that I had and have such supportive people around me and that I was able to persist and find the silver lining to what could have been my neverending cloud. I’m grateful that I got to meet Shawna when I did, and I’m especially grateful that I can posit ideas into the world that will hopefully make it a better place. That’s all a teacher really wants to do, right?

Meeting of Minds

When you go to a teacher convention, at first, you never really know what you are going to get, but professional development as an educator couldn’t have gotten any better. We briefly met through a mutual colleague, and soon after, began exchanging ideas and compiling solutions on what continues to be a pursuit and evolution on how

to integrate STEM with Music in the most meaningful and engaging ways possible. Although we are both trained music educators, our work and approaches aren’t just for integrating STEM into the music classroom. These approaches translate just as well for any STEM area teachers who are interested in connecting their content with music.

We often discuss the connections between STEM and Music, as well as the personal journeys each one of us has taken to get to the current understandings we hold by way of having numerous conversations over the years. We don’t purport to have eyes and ears in every classroom in the world; however, we are able to determine certain things based on anecdotal evidence and quantitative data that supports the anecdotal evidence.

The process of researching for this book comes mostly from being personally involved with this subject for many years. Between the two authors, we each bring our own personal experiences that we’ve had in and out of the classroom that shape our goals for our students and our goals for ourselves. The trial-and-error portion of engineering design, year after year of teaching lessons, finding what works, what doesn’t, is a large part of our field research. Seeing children and the society they are being raised in, seeing and being the change is our field research. This isn’t to say that the contents of this book are purely anecdotal, but they fall to the same perspective of personal lens that any reflective classroom teacher acknowledges. Reflecting, refining, and trial and error are inherent in how we’ve researched, tested, and compiled the contents of this book.

What Is Our Philosophy?

We believe in play and the idea of free experimentation and exploration. Free experimentation, from a structural standpoint, needs to be more structured in some instances when delivering education. Definitions, standards, alignment, assessment, language, and cognitive demand level need to be communicated, calibrated, and synchronized. What works for students and teachers in one town or school may not necessarily work in another, but through the use and alignment of national standards we aim to create instructional plans that are applicable universally.

The term “integration” refers to taking from many to create a new whole. When approaching the integration of STEM with Music, we are foundationally aligning a STEM standard with a Music standard to authentically and equitably teach and assess in and through both standards. Standards alignment is the backbone of integrating STEM with Music so that it universally speaks to more teachers, students, and classrooms, which is our goal. To create distinction from music as an art form, we the authors denote the teaching discipline of Music with capitalization throughout this work, holding it to the same expectation of capitalization as the teaching disciplines included in STEM.

We spend a good deal of time, and pages, devoted to explaining the details included within our instructional process, namely, lesson/unit plans, for integrating STEM with Music. While we acknowledge that this can get a bit heavy, we feel it is necessary to truly understand why and how to create authentic experiences. Either it’s been way too many years since you took educational classes in college or no one really explained the what and the why behind lesson/unit plan components. Our goal is to give the reader a better understanding of why various components are included and necessary within planning an instructional process.

Using This Text as a Manual for Instruction and Planning

This text serves as a flexible document that seeks to uncover, define, and detail the path toward the instructional goals that we have previously stated. We begin with a heavily theory-based approach and then connect that theory to practice. The organization of the text is influenced by the engineering design process, as discussed by the creators of the Next Generation Science Standards. Much as with many other courses, we believe that without a strong foundation, any practice built on top is not of the quality that we strive to create or promote. To begin with this process, we must define a problem and its context, or in essence, develop the theory and define the pillars that support our understanding. After this, we then develop solutions based on the applied theory, creating a criterion for the use of assessment and aligned standards. Lastly, the optimization of these understandings is achieved through the developing and offering of the included instructional plans.

To be an expert in all the topics and concepts presented is not required or expected for the reader to progress through the chapters. With a better understanding and more time to digest the information, the application of these ideas and approach will, like any good-quality teaching strategy, continuously improve and develop.

As we transition in the text to the K–12 instructional plans, there are many concentric circles these plans inhabit. You, the reader, will find adaptations, cross-compatibility, assemblances of vertical articulation, and the potential for this text to quite literally serve as the foundation for a K–12 course curriculum. Through our love of music and pursuit of providing impactful and relevant experiences for students, we have created these plans for teachers to use immediately in the classroom.

What Are the Foundations of an Integrated Approach to Teaching and Learning?

I don’t think there’s a kid in America, or anywhere in the world, who gets out of bed in the morning wondering what they can do to raise their state’s reading standards. They get out of bed if they’re motivated by their own interests and their own development.1

Sir Ken Robinson

When a teacher walks into the classroom, their mental toolbox is typically brimming with objectives that they have curated for their students. While guiding the approach in defining student achievement, these objectives can also run the gamut and sometimes fall into an unremarkable sea of “the students will be able to . . .,” making the essence of the art of teaching unclear. One could consider that the core of teaching lies in the act of sharing human perspective with one another, and when walking out of the classroom, teachers have not only shared their own worldview, but have also hopefully changed the way their students view the world for the better.

A teacher’s perspective on the world undoubtedly affects how they teach, but there is an abundance of examples revealing the dichotomy between how teachers and students view the same world. Whether the subject is an overall opinion on broccoli, or how tall playground monkey bars really seem, the juxtapositions between our worlds can sometimes be vast. By recognizing and celebrating shared differences, those differences have less of a chance of dividing a community, and more of a chance of bringing that community together. This inclusive idea is relevant to many music educators in the sense that they often are the facilitators of individual artistic expression for students while simultaneously working to maintain a delicate balance in their pursuits of uniformity within performing ensembles. However, at what point does celebrating differences in opinion and terms defined result in diminished effectiveness in an educational structure, which could then lack an actionable consensus? For instance, is it to be celebrated if a student in class voices that, in her opinion, which is different from that of the rest of the class, “Wade

1 Sir Ken Robinson (2013, May 10), “How to Escape Education’s Death Valley,” TED talk. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wX78iKhInsc

Integrating STEM with Music. Shawna Longo and Zachary Gates, Oxford University Press. © Oxford University Press 2021. DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780197546772.003.0001

in the Water” is not a traditional African American spiritual? Situations that are subtly and overtly problematic can arise from issues of key differences in the way teachers, students, and a learning community tend to define a seemingly simple concept or word. These differences can be the result of over-arguing semantics, core disagreements in philosophy, or a simple lack of knowledge resulting in a fundamental misunderstanding. Whatever the reason may be, to see how someone views the world is to see how they define and recognize the parts of their world that matter to them most. The things that make us and our views different can cause us to become divided and tribalistic, unified under new and greater perspectives and ideas, or perplexed by misconceptions of seemingly simple material. For teachers to effectively share their perspective with their entire learning community, a shared understanding needs to be cultivated of basic definitions so as to move the conversation forward. This can be said for when advocating for any new method or initiative in a variety of contexts. When misconceptions go unaddressed in any context, like trying to figure out “who’s on first?,” these misconceptions can rear their heads in ugly ways during unexpected moments.

What Is Music Technology?

For instance, at the end of a long but overall successful year teaching choir, a young music educator in the suburbs of New England sought written feedback from their students pertaining to their experience in their class. Since the school district’s yearly initiative was to promote and enhance the usage of technology in the classroom, this was something the young teacher worked hard to incorporate into each and every lesson. From synthesizers being played at the concert, to daily classroom assignments being recorded and uploaded via the web, educational and music technology was in every nook and cranny of the students’ experience.

This made it all the more surprising to the teacher when, while looking at the online forms filled with feedback, they saw that many of their students responded to a particular question that made them scratch their head, wondering for a second.

The question had been posed:

Q: How do you feel the incorporation of technology affected your experience the most in choir this year? How would you like to see it integrated next year?

Students responded:

A: N/A. I don’t know

“Not applicable”? “I don’t know”? After further questioning and discussion, it was discovered by the teacher that the students said “N/A” because they did not think of their online classroom discussion forums, sight-reading programs, or the introduction of mobile devices for assessment as “technology integration.” Students just didn’t view the services or devices used as “technology.” They instead perceived these devices and programs as just “things” that were already embedded in their world. While considering the fascinating societal and educational implications of how younger people can have a decidedly different definition of “technology” than those who are older, it’s also notable that the students who did not define technology in the same way the teacher defined

technology were also unable to demonstrate an ability to synthesize ideas and share opinions on the method, frequency, and quality by which technology was and could be incorporated in the classroom.

As an educational stakeholder, what does this say about developing a sense of ownership for the individual student? How can students have their voice heard when they haven’t been given command over the language? How can we keep students from calling a theremin “educational technology” and their online learning management system “music technology”? Can’t a theremin be used for education, and an online learning management system help a music class? Clarification is needed if we truly aim to integrate technology for the sake of improving student understanding and achievement and not just for the sake of integrating.

To lay it out simply, finding a good way to break down the idea of “technology” into different categories for students and the greater learning community helps when discussing integrating STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics) with Music. The categories of technology listed in Table 1.1 are far from the only identifiable types of technology, and are far from the only way to divide types of technology. While most every example of technology can belong in at least one other category, each example shows a majority of reliance on, or application with, each individual section.

To be clear, music technology can be used in an educational context, just as educational technology can be used in a musical context, but they are two separate sides of the same coin. “Music technology” should be used to define devices, services, or media that have been developed and produced for the main functional purpose of enhancing musical experience and outcome. “Educational technology” should be used to define devices, services, or media that have been developed and produced for the main functional purpose of enhancing educational experience and outcome. A digital- sampling pad would first be considered as an example of music technology, even if it was used to teach electronic music performance in a class, while a computer- aided assessment would first be considered as an example of educational technology, even if it was used for a music class. While these examples of technology

Table 1.1

Technology Type

1. Science/Chemical Technology

2. Engineering/Manufacturing Technology

3. Mathematical/Computer Technology

4. Education Technology

5. Music Technology

Key Examples

DNA testing, super-hydrophobic materials, electrochemical energy storage (lithium ion batteries), nuclear power

Suspension bridges, motor vehicles, commercial mass-production machines, 3D printers

Data visualization, autonomous machines, internet connectivity, mapping and direction services

Online learning management systems, smartboards, document cameras, online instructional videos and discussion forums

Digital Audio Workstations/interfaces, guitar pickups, synthesizers, looping pedals

use and serve multiple functions, their categorization stems from their most accepted and common functionality.

When integrating forms of technology into instruction, the act of merely integrating does not automatically result in a higher-quality educational experience. Teachers can avoid the pitfalls of integrating technology for the sake of technology integration by using a model for assessing the function and quality of technology integration (Ruben, 2015). Popularized by Dr. Ruben Puentedura, SAMR (Substitution, Augmentation, Modification, Redefinition) separates integration into a row of categories that grow increasingly difficult to plan and achieve (Table 1.2). While each step gets more difficult to achieve, each step also increases how meaningful the potential impact can be for activities, lessons, and students.

Before applying any model for assessing technology integration, like SAMR, it’s imperative for teachers to ensure that their learning community understands and comes to a degree of consensus on what is defined as technology and how different tools and topics can be identified. “If used wisely, technology becomes a tool for meaning making and developing agency for learners” (Ruthmann, 2020, p. xviii).

Table 1.2 SAMR Component Definition Example

1. Substitution Tech acts as a direct tool substitute, with no functional change.

2. Augmentation Tech acts as a direct tool substitute, with functional improvement.

3. Modification Tech allows for significant task redesign.

4. Redefinition Tech allows for the creation of new tasks, previously inconceivable.

Using PDF files of sheet music for students on tablet computers.

Using an app to make score markings on PDF sheet music for students on tablet computers.

Creating music using notation software/apps on a computer.

Exporting MIDI* data from student-made compositions to a DAW† for use in a song.

* MIDI (Musical Instrument Digital Interface)—A standard of communication for how computers handle musical data for the composition and performance of all technical parameters for music making. MIDI signals do not contain audio and are used mostly for computer-based/assisted music making.

† DAW (Digital Audio Workstation)—Any hardware or software that allows a user to arrange, perform, compose, and process audio, e.g., Garageband, Logic X, Ableton Live, Soundtrap, Soundation, and Pro Tools.

What Is Cross-Curricular?

In the realm of misidentification and misconception, consider a third grade class memorizing each US state in alphabetical order. The teacher decides that by singing a

song containing the name of each state in alphabetical order, students will memorize the states better. Is this considered cross-curricular?

How about a middle school percussion sectional analyzing how the density of a mallet affects the sound of a drum being played? Is that considered cross-curricular? For both examples, whether or not these scenarios are considered cross-curricular depends mostly on what’s happening behind the scenes and before the actual instruction begins.

The International Bureau of Education, partnered with UNESCO, defines crosscurricular education as “an approach to formulating curriculum that favours the dynamic use of learning topics and themes to be covered and skills/competencies to be developed in a number of learning areas across the curriculum” (International Bureau of Education, 2019).

Under this definition, if skills are to be meaningfully developed in varying learning areas, then let’s take two classroom versions of the same lesson as an example:

In choral classroom “A,” students are learning a piece from Switzerland that incorporates vocalization that is inspired by the art of yodeling. So then, while handing the piece out to students, the teacher puts a map of Switzerland on the smart board, points to it, and begins teaching rhythms and melody.

In another choral classroom, classroom “B,” students are learning the same piece from Switzerland. However, the map on the smart board includes detailed topography, which leads into a conversation about the history of yodeling in the region and its relationship to the mountainous terrain. A science teacher then helps students in the classroom learn the acoustical physics that pertains to how pitch and resonance can travel great distances. Students will then be given time to manipulate a browser-based computer simulation of the phonatory process, mouth, and larynx.

While the teachers in classroom “A” and “B” may feel that they are both teaching a lesson that incorporates cross-curricular learning and high-quality technology integration, the teacher in classroom “A” would unfortunately be mistaken.

It might be deduced from the description of learning and activities taking place in classroom “B” that that teacher has used content standards and objectives that may be found in content areas other than music to engage students in a deeper and more meaningful learning experience. This enhanced learning experience could more effectively hook students who identify as having more strength in content areas other than music, like geography, physics, and anatomy, and can also develop a more personal connection to the material taught by the teacher. Not only can positive collaboration between colleagues be observed in classroom “B,” but the scenario ends in an example of extremely high-quality technology integration, or Redefinition within the SAMR model, by way of having students virtually visualize and manipulate a vocal tract, thus engaging students in a task that enables a higher Bloom’s Taxonomy level through the synthesis of knowledge previously thought to be inconceivable.

In criticism of classroom “B,” a teacher or administrator could perhaps, in their opinion, find fault in how long it took those students to actually start learning the notes and rhythms of the specific piece of music. Isn’t that the point of a music class? To learn the music? A healthy and well-reasoned response to that criticism is similar in the way music educators should defend the importance of teaching musical literacy in classes for performing ensembles. Teaching musical literacy to students of any age takes time. This

is time that could arguably be spent just learning the music by rote and singing it back on command, so why spend the time? Critical and performing ensemble pedagogy has taught us that teaching literacy to students is how teachers can empower students in the rehearsal process. When given the tools and agency to decode essential material and thus be able to think critically, students develop higher levels of achievement, retention, and ownership in the rehearsal process.

Students in classroom “B” will have taken longer to get to the rhythms and notes in their piece, but they will be equipped with a multifaceted wealth of knowledge that will help drive their learning forward and create a more meaningful experience. Isn’t that the point of a music class? To learn the music through meaningful experiences? The approach in classroom “B” provides a bigger picture and deeper connection to the content. It also affords students opportunities to make real-world connections to content. Using connections as the driver of experiences with content benefits not only the students but the teacher(s). Recognition of what these connected topics truly look like and how they are defined are the strongest steps toward impactful advocacy.

This is also why, when guided by Critical Pedagogy for Music Education (CPME), traditional music learning in schools is not so distant from a more modern or alternative approach to music learning in schools (Abrahams, 2005).

What Is Arts Integration?

Misunderstanding frequently occurs when teachers talk about arts integration. As defined by the Institute for Arts Integration & STEAM, “Arts integration is an approach to teaching and learning through which content standards are taught and assessed equitably in and through the arts” (Riley, 2019). This approach to teaching and learning occurs when any non-arts content is intentionally integrated with an arts content through the assessment, alignment, and positioning of the content standards.

The key word is intentional. Are you intentionally aligning two standards? In order to authentically apply arts integration strategies, teachers of the arts need to understand what topics and standards are covered within the non-arts content areas. As a music teacher, you should have an understanding of what big topics and concepts the other content teachers are covering throughout the year within their scope and sequence. If you can authentically draw out those non-music topics that naturally relate to the music topics, concepts, and/or skills that you teach, then you will deepen student learning within the music class and make connections to the other content area(s). This will not only strengthen their learning in the class, but also in the other content area(s). As the teacher, if you personally happen to cover the material first, then you are also helping your colleagues as students are pre-taught and exposed to non-arts topics/concepts/skills in music. It brightens my day when other content teachers stop me in the hall and are, at first, shocked and excited that their students had a baseline of knowledge when they started a new unit because they learned about it in music! When you embrace this approach regularly, your colleagues might be less shocked and have a better chance to enjoy the opportunity to dig deeper into their content, while making connections to the arts as they recognize and draw upon the relatedness between the contents.

This won’t happen overnight—it takes time, consistency, and trust. As a teacher of the arts, it takes time to look at the content standards outside of the arts. It can also help to have a colleague in each department that you can trust, lean on, is willing to brainstorm with, and answer your questions without judgment. A quick five-minute conversation with another content teacher can give you a substantial list of the topics or concepts that they cover throughout the school year. If you can have this conversation with a teacher in each content area, then you will gain a better understanding of the scope and sequence of topics, concepts, and standards that your students are encountering during the rest of their school day. This is also a way to start building trust with your colleagues and start conversations that can eventually lead to the other content teachers bringing your arts content into their classrooms!

Circling back to the word intentionally, do the verbs included within the arts and non-arts standards agree? Once you have selected the arts standard that you will be covering and have determined the other content area that you want to integrate, find the content standard that aligns with the arts standard. It can be very overwhelming to dive into content standards, especially those out of your area of expertise. This is where that relationship and trust that you have developed with your colleagues can help you out. If you go to a colleague who teaches the content area that you want to integrate and ask their opinion, consider starting by giving them a brief overview of your lesson/unit idea, explaining how you will bring their content into your arts classroom and then ask them what content standard will best align with the arts standards. Once you have the standards for both content areas (arts and non-arts), then you will want to take a look at the verbs included within each standard. Does the intended action associated with each verb agree?

For example, let’s look at the alignment of a math and a music standard (Table 1.3):

The verbs included in these two standards are “model” and “demonstrate.” Clearly, these two verbs agree and are related in the action that the students will be doing.

Now, let’s take a look at aligning that same math standard with a different music standard (Table 1.4):

Table 1.3 Standard Description

CCSS.MATH.

CONTENT.K.G.B.5*

MU:Cn11.0.Ka†

Model shapes in the world by building shapes from components and drawing shapes.

Demonstrate understanding of relationships between music and other arts, other disciplines, varied contexts, and daily life.

* Source: National Core Arts Standards © 2015 National Coalition for Core Arts Standards. Rights administered by State Education Agency Directors of Arts Education (SEADAE), www.nationalartsstandards.org. All rights reserved.

† Source: © Copyright 2010. National Governors Association Center for Best Practices and Council of Chief State School Officers. All rights reserved.

Table 1.4

MU:Re7.1.Ka* With guidance, list personal interests and experiences and demonstrate why they prefer some music selections over others.

* Source: © Copyright 2010. National Governors Association Center for Best Practices and Council of Chief State School Officers. All rights reserved.

The verb “model” and “list” do not agree. Creating a list does not authentically or naturally relate, or connect, with modeling or building shapes.

Another aspect of intentionality within arts integration occurs within the following question: Are you intentionally and equitably teaching both standards throughout the lesson or unit? Discussing a science concept for five minutes within multiple lessons of music class does not display equity between the contents. This is not to say that each content must have the exact same amount of time spent during a lesson sequence, but it should be close. And further, the teacher needs to be intentionally discussing both integrated contents throughout the lesson sequence. Content that is used cannot solely be in service to other content, nor should it be considered more important than other content. There is no hierarchy despite the fact that we all need to serve as our content’s best advocates.

Related to that, a critical aspect of integrating standards is by intentionally assessing standards from different content areas. This is where most teachers answer with a resounding “no.” Often, teachers don’t feel comfortable assessing a content area that is not within their certificated area. But, if you expect your students to learn through the integration of the contents and show what they have learned, then you as the teacher should be able to assess the standards that you taught equitably throughout the lesson(s).

In turn, if the standards are not authentically and naturally aligned, or equitably taught and assessed, then the lesson probably only qualifies as arts enhancement. In arts enhancement, the arts are being used in service of another content, like singing a song as a device to remember a concept, coloring a picture, or drawing a diagram. The arts are used to make learning “stick” better and there isn’t anything wrong with that . . . it’s all about intention. Frequently, teachers integrate the arts, but without knowing it or acknowledging it. Oftentimes, the teacher just needs to align an arts standard to their lesson (and assessment), and immediately the lesson is kicked up just a notch to become true arts integration. Remember, it’s all about intentionality and recognizing the relatedness between the arts and non-arts contents.

What Is Collaboration?

Collaboration can be defined as the process of joining efforts with one or more people with a specific goal in mind. And although it would seem logical that teachers would collaborate to ensure that they are making deeper connections for their students on a daily basis, this is not typically the case. Most teachers are overworked and overtaxed with more content and standards to cover than they can fit into the limited time they have with their students. As arts teachers in a K–8 setting, we often serve as the “prep” time

for the other content teachers. Although schedules vary based on building and district needs, most arts teachers work on either a five- or six-day schedule, or teach markingperiod or semester-long classes. This also doesn’t account for pull-out classes like speech, therapy, counseling, etc.; inclement weather days; and the plethora of other disruptors to the schedule.

This constant struggle with time often leaves teachers feeling and being stuck in their classrooms. Over time, this can compound into total isolation. Once we begin to recognize the relatedness between contents, we can then utilize collaboration with our colleagues to break down these silos of isolation. Arts integration and STEM initiatives are effective means to encourage collaboration between arts and non-arts teachers in order to break down the silos of isolation. Once broken down, the resulting collaboration will improve school climate and culture, leading to deeper, more authentic student learning.

Collaborating with teachers from different subject matters to construct a student-driven arts integration project is a unique and inspiring experience. I teach 7th grade physics. Within the physics curriculum, I focus on different kinds of waves and the science of sound. Each educator typically has a different way of approaching content matter when teaching students. We teach in a way that we feel best connects with our students; a way that ideally has the most stimulating and positive impact on them. When my colleague, the music teacher in our middle school, approached me about ideas for a sound waves project for my students I was very interested. What I did not anticipate was the power of combining our different teaching styles, research methodologies, strengths, and unique approaches to the subject matter. We initially brainstormed together, then worked independently to construct parts of the project, and continued to periodically meet for continued collaboration. The combination of gathered information, teaching tools, and strategies generated a significantly more powerful project than if I had developed the project on my own. The end result was a project that was attention-grabbing, fascinating, and educational! The students learned and loved it.

Leeann Juliano, science teacher, middle school

What Should STEM with Arts Integration Be?

STEM with arts integration should be about creating student-centered experiences that focus on critical thinking, inquiry, and dialogue, and are driven by these examples so as to equitably integrate STEAM content areas. Most schools today are focused on high-stakes test preparation where students find the right answer and move on. The test-preparation model inherently fails to address the need for more soft skills to be taught in classrooms.

Soft skills do not depend on acquired knowledge or job-specific skills. Instead, they are related to how you work with others. Soft skills are a part of our personalities and behaviors that can help or hinder our success as adults in the workplace or as students in school. They can also be connected to the Habits of Mind, which exist

across multiple contents including Science, Engineering, Mathematics, and Artists (Riley, 2020).

By using STEAM strategies for learning, the classroom focus shifts to more soft skills that will serve students well in their future careers and lives in general. It allows students the opportunity to practice skills like perseverance and grit. Even if students run into roadblocks or fail, they need to have the ability to stay the course and complete the task at hand.

As shown in Table 1.5, there are habits or soft skills found across these contents that can each be integrated into a theme or idea. Although there are not any Habits of Mind specifically for technology, the engineering habits are synonymous to the habits or soft skills used in the field of technology.

One may think that what sets STEAM apart from arts integration is the specific content standards that are being integrated: arts integration can integrate any non-arts content area with the arts while STEAM integrates science, technology, engineering, and/ or mathematics with an arts content area. But, of course, it’s not that simple. “STEAM is an educational approach to learning that uses Science, Technology, Engineering, the Arts, and Mathematics as access points for guiding student inquiry, dialogue, and critical thinking. The end results are students who take thoughtful risks, engage in experiential learning, persist in problem-solving, embrace collaboration, and work through the creative process” (Riley, 2020). In addition to the content areas being integrated with the arts, STEAM focuses on student inquiry, dialogue, and critical thinking, which will result in a more student-centered, student-driven classroom.

Simply putting on a piece of music, coloring a picture, or reading a play are not examples of arts integration or STEAM. It is important to note, however, that in both arts integration and STEAM approaches, student learning occurs when creativity drives the authentic and intentional connections between the knowledge, skills, and processes of non-arts and arts content areas. The encouragement of creativity and innovation can deepen student learning in both content areas.

What Is STEM’s Connection to STEAM?

In 2009, the Obama administration announced the “Educate to Innovate” campaign in order to draw attention to the student deficiencies occurring in STEM. The purpose was to motivate and inspire students to increase their interest and success in, as well as to pursue careers in STEM fields. “STEM is a curriculum that is based on the idea of educating students in four specific disciplines—science, technology, engineering and mathematics—in an interdisciplinary and applied approach. Rather than teach the four disciplines as separate and discrete subjects, STEM integrates them into a cohesive learning paradigm based on real-world applications” (Hom, 2014). The national focus on STEM contents created a race for school districts across the country to rethink and revamp their educational programs in order to pursue available funding directly tied to STEM contents, teaching strategies, and curriculum. A missing piece of the puzzle was that many, if not most, teachers were not trained, equipped, or certified to teach these types of STEM courses.Time, energy, and money needed to be spent on providing highquality and sustained professional development for STEM teachers so that they could

Table 1.5 Habit/ Soft Skill Contents Used in

Apply our previous knowledge when exploring, designing, creating, producing, presenting, and performing new creative ideas and/ or work(s).

Create ideas and/ or works that generate new solutions and/ or experiences.

Effectively communicate our creative ideas and/ or works to others when we find common terms or language.

Foster an openness to continual learning so that we may grow as individuals and expand our creative work.

Strive to be flexible and keep our minds open to new creative ideas, opinions, and experiences especially when we meet “failure.”

Use mental pictures to imagine and/ or “see” endless possibilities in envisioning new ideas, designs, solutions, creations, and/ or performances.

Willing to experiment and search for innovative ideas and solutions to transform and revolutionize our creative work(s).

Spend time and energy listening to varied viewpoints and perceptions to inform and evolve our creative ideas, opinions, and work(s).

(continued)

Applying Previous Knowledge to New Situations

Creating

Communicating

Continual Learning

Flexibility

Imagining

Innovating

Listening

Persist in working through our ideas and completing our creative work over a length of time despite difficulty and/ or fatigue.

Practice continual selfreflection and are open to constructive criticism of our creative ideas, solutions, and work(s) in order to nurture and encourage our desire to make better work(s).

Take responsible risks and push the confines of our perceived boundaries in order to continually challenge our creative selves to grow through our ideas, solutions, and work(s).

Grow as creative and cooperative individuals through working in groups where we develop and practice effective and necessary social skills in order to access a larger base of knowledge and experience.

Source: Costa, 2008. Continued

Persisting

Effectively and inquisitively ask the right questions to fill in the gaps between known and unknown knowledge while creatively developing ideas, solutions and work(s). Reflecting

Questioning

Risk

Thinking Interdependently

understand how to find connections between the contents and present the material in an engaging way to students. The underlying purpose was to encourage teachers to see how STEM contents relate to each other and to encourage collaboration among all teachers. This, in turn, would trigger the development of critical thinking and creativity within students.

Currently, most STEM teachers have no previous professional experience with this type of teaching and learning throughout any part of their education—from elementary to secondary to college or beyond. Their experience was grounded in rote memorization, minimal real-world application, and a focus on finding the “right” answer when it came to testing, whether or not they acquired the knowledge and skills being taught. The arts can provide an effective way to increase the opportunities for creativity in the classes that students feel might not necessitate any creativity.

Through the inclusion of creative activities in STEM, we are allowing students to make real-world connections between the various contents and skills that they are learning. Creative activities allow students the opportunity to think outside the box and shift the focus away from finding the answer where there is only one specific end result. This model allows students to focus instead on the journey itself, or the process it takes to move toward the goal. With this in mind, we can view this model as a means for increasing college and career readiness in the 21st century for our students. Adding the “A” to STEM can increase student engagement, motivation, and self-confidence through interactive and group learning (collaboration) opportunities, especially for students who feel as if they won’t be successful with STEM instruction due to negative past experience with traditional academic models. The arts give us different pathways to see, hear, and understand the world in ways we may otherwise miss, and they invite students who might otherwise be unwilling to invest time and effort to explore something new.

The “A” in STEAM can represent visual art, music, theater, dance, and/or new media arts. Many music classrooms are already integrating STEM contents into the classrooms through the use of music technology. The arts integration component is valid if it is authentically and intentionally taught and assessed throughout the lesson(s). Here are some examples of where arts integration, or the foundation of STEAM, can be occurring in Music and the STEM contents that are or can be integrated into the concepts or practices:

• Counting and composing rhythms (technology, engineering, math)

• Sound waves and amplitude (science, technology, engineering)

• Performing using Boomwhackers or any other traditional instruments (science, math)

• Performing using virtual instruments (science, technology, math)

• Music technology cloud-based programs like Noteflight, Groovy Music, Morton Subotnick’s Creative Tools, or O-Generator through MusicFirst Classroom (science, technology, engineering, math)

• Composing/arranging/recording using Soundation, Soundtrap, or GarageBand (science, technology, engineering, math)

• Makey Makey, Little Bits Synth, Jamstik, etc. (science, tech, engineering, math)

• Music technology apps and/or websites (science, tech, engineering, math)