Introduction

Midwest Bedrock

Like many midwesterners, I spent my youth denying I was midwestern. We all go through this phase. Other places just seem so much more exotic. But my denial was of a different sort. I knew instinctively that this little pocket where I lived—Dubuque, Iowa, along the Mississippi River—was not the typical Midwest. This I could identify with. This was certainly not the Midwest I thought I knew when I traveled even short distances beyond the Mississippi valley.

I can’t put my finger on when it happened. I’m sure it was quite gradual. Perhaps it was when I began dating my wife Dianne more than forty years ago, as we quickly fell into the habit of spending time outdoors together and seeing new places, even if just a short drive from town. When our first son, Paul, was born, we bundled him into a back carrier and hiked amid the autumn gold of birch leaves at the Mines of Spain along the Mississippi. I remember the white trunks etched against the blue sky. After our second son, Brian, came along, we perched them both in child carriers on our bicycles and rode the former railbed on the Heritage Trail, snaking west across Dubuque County. That carrier was on the back of my bike so long that I still dismount so as to not swing my leg across a phantom child seat. When our daughter, Angie—our third and youngest—arrived, Dianne and I were finally outnumbered, but we still took our family chaos hiking and camping. Once, at Pikes Peak State Park about an hour from home, we

unloaded and set up camp, and then discovered that Angie had brought no shoes, sandals, or flip-flops. Who wears shoes in the summer?

We began to discover not only a broader Driftless Area, but a more varied and interesting Midwest than I had ever thought existed. We scaled the blocky, purple quartzite bluff five hundred feet above Devil’s Lake in southwest Wisconsin. We canoed the frisky Wapsipinicon River through eastern Iowa. We camped at Iowa’s Backbone State Park where we played in the sandy creek bottom and hiked “the Backbone,” a hogback ridge, to its narrowest point where it overlooks meanders of the Maquoketa River on either side of the ledge. Over the years we spent summer weeks in fishing resort cabins in the Wisconsin north woods and Minnesota lake country.

And I came to terms with the Plains, too, as I imagined the weight of mile-high glaciers pressing down, crawling southward with a slow certitude, and scraping the landscape flat. I imagined the glacial till sprouting a few grasses as the glaciers retreated, and those grasses blossoming into the prairie that produced and protected the deep, fertile soils that grow corn and soybeans today.

Our outdoor tastes weren’t limited to the Midwest. Dianne and I camped at Rocky Mountain National Park on our wedding trip. As the kids grew older, we also took them to Rocky Mountain, and to Yellowstone, to the Badlands, the Grand Tetons, Yosemite, and the John Muir Woods. When they were young adults, they spent a week with me in Ireland while I was teaching in Dublin. Dianne and I explored Ireland, Germany, England, and France, spending as much of our time as possible on long outdoor hikes and walks in the mountains, around lakes, beside streams, and in hills far away from the famous cities.

The glamorous places—the Rockies, the Tetons, and ocean shorelines—impress the senses with their immensity and grandeur. Nature in the Midwest rarely competes in height, depth, or range.

Midwestern spaces are instead “grace notes.” Musically speaking, a grace note is an ornamental sound so tiny its time value is not counted in the rhythm of the bar. As outdoors spaces, the Midwest’s grace notes include small county parks with clear, cold trout streams as well as large refuges that are tiny in public awareness.

These midwestern grace notes lie near our homes. We will turn a corner on a winding road in the Driftless to find a rock tower hovering above a meandering stream. On that long interstate drive we will see in the distance the curious crests of Nebraska sandhills, and a detour onto the backroads will reveal to us that lonely yet profound landscape. Appreciating the

prairie requires finding the universe in a square yard of ground. These are gift pennies, making us rich only in their moments of sublimity.

And they are bedrock. Literally, in terms of limestone bones of earth that rear up out of the soil in the Driftless. Figuratively, they are the solid physical places in a nation awash in uncertainty.

So what is Midwest Bedrock?

I suppose a more basic—or bedrock—question should precede this: What exactly is the Midwest? Geographically, the United States Census Bureau defines the Midwest as the following twelve north-central states: Ohio, Indiana, Michigan, Wisconsin, Illinois, Minnesota, Iowa, Missouri, North Dakota, South Dakota, Nebraska, and Kansas. In common usage, some will rule out Ohio as too eastern, too much like forested, coal-mining, industrial Pennsylvania. Some will drop North and South Dakota as too western. Others consider Missouri too southern, Kansas too south-central. I like the Census Bureau’s no-nonsense deliberations. In terms of gathering census data, there are four US regions: the Northeast, the South, the West, and the Midwest. There’s something midwestern in that simplicity.

The term seems to have originated out of nineteenth-century US expansion. The Midwest states east of the Mississippi were once simply called the West or the Northwest (hence Northwestern University in Chicago), until the Louisiana Purchase added vast new regions to call the West. Still not quite East and definitely not South, the term Midwest gradually took over.

That is, when it wasn’t being called by other names. A different name like “Mid-America” would be less confusing than “Mid” West. Most kindly, some call the Midwest the “Heartland,” suggesting not only its physical centrality but also, well, a certain bedrock, plainspoken personality of its people. “Prairie States” is a fairly accurate descriptor of its historical flora, but ignores the vast historical stretches of forest and oak savanna. “Plains States” plays to a topographic stereotype and minimizes the Midwest’s varied landscapes while likewise suggesting a rather milquetoast state of mind. What excitement could come from the Plains?

And worst of all is the pejorative “Flyover Country,” so-dubbed by eastern and western elites flying between coastal cities. Many on the coasts t hink they know us: I’ve tried convincing easterners and westerners that there are considerable hills where I live along the Mississippi River.

The problem lies in the desire to quickly label a region without much thought to its nuances. The Midwest is anything but homogenous. Its

landform (or physiographic) regions run from the glacially flattened to the rugged and rocky. On the east it is wet and humid, on the west it is high and dry. The northern midwesterner takes a certain pride in getting buried in snow while the southern midwesterner comes to a halt in the wake of a few inches.

Aware of its diverse landscapes, we call the whole region “Midwest.”

So that leaves bedrock.

Most of the Midwest’s literal sedimentary bedrock coalesced under ancient seas while the North American mantle drifted over the equator from t hree hundred to five hundred million years ago. Limestone formed when those seas teemed with shelled creatures whose hulls sank to the ocean floor after they died. Compressed and chemically altered, they exuded lime, which hardened into rock—and created some pretty cool fossils. Sandstone formed in shallower seas near shorelines, as layer on layer of sand packed into stone. Shale formed where muddy rivers emptied into the sea. With the land rising and falling and rising again, a slice down through Midwest bedrock today typically produces alternating layers of limestone, sandstone, and shale.

Northern Midwest bedrock has different origins. The granites and basalts of northern Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Michigan attest to oncegrand mountains worn away by time and repeated glaciers.

Try as I might, I can’t completely avoid slipping into the metaphorical sense, the somewhat tired cliché of the Midwest being the psychological bedrock of the nation. This book makes no attempt to define a midwestern mindset or culture. Much has been written about “midwestern nice,” i n terms of both friendliness and a certain passive-aggressiveness in not speaking of difficult matters—except behind someone’s back. There is also a perception of the Midwest having a work ethic valued by employers and particularly noticed when midwesterners emigrate to other regions of the country. There may be certain truths to these, but I suspect they are also exaggerated. That said, you may need to excuse me if my vision of “Midwest Bedrock” occasionally suggests a regional personality. It’s hard not to love your neighbor here.

This book, then, is a search. Geographically, there is no denying that the Midwest is at the center of the nation. But what is at the center of the Midwest?

Q

It is worth stating a few things that this book is not about. It is not about the Midwest’s politics, but suffice it to say that I have grown increasingly

despondent about my home region’s political landscape. I once took pride in much of the Midwest’s “purple-state” status, but the region has grown more extreme over the last decade. However, such changes don’t happen in a vacuum. Declining rural population and increased poverty expresses itself in political ways that—in my opinion—don’t always serve our best interests. I also lament the lack of political concern for our polluted midwestern streams and rivers.

Nor is this book about the Midwest’s cities, but it might be worthwhile to set straight some misperceptions of the Midwest as excessively rural. Nine midwestern cities are among the fifty most populous in the United States. Below are their national rankings and populations according to the 2020 US census:

3) Chicago, IL (2,670,000)

14) Columbus, OH (914,000)

16) Indianapolis, IN (887,000)

26) Detroit, MI (664,000)

30) Milwaukee, WI (588,000)

39) Kansas City, MO (502,000)

41) Omaha, NE (480,000)

46) Minneapolis, MN (439,000)

50) Wichita, KS (391,000)

Cleveland (OH), St. Paul (MN), Cincinnati (OH), St. Louis (MO), Lincoln (NE), Fort Wayne (IN), Toledo (OH), and Madison (WI) likewise place in the top one hundred.1

The twelve Midwest states accounted for 68.8 million of the nation’s 331.5 million people in the 2020 census.2 That means we represent 21 percent of the nation’s population in 24 percent of the nation’s states, pretty much right on average as a region. So much for the Flyover Country.

Dianne and I enjoy the occasional day in the city, visiting our daughter in Chicago and taking in the museums, or investigating the St. Louis Gateway Arch or the parks of Minneapolis. For the most part, though, cities are what we pass through on our way to more inviting places.

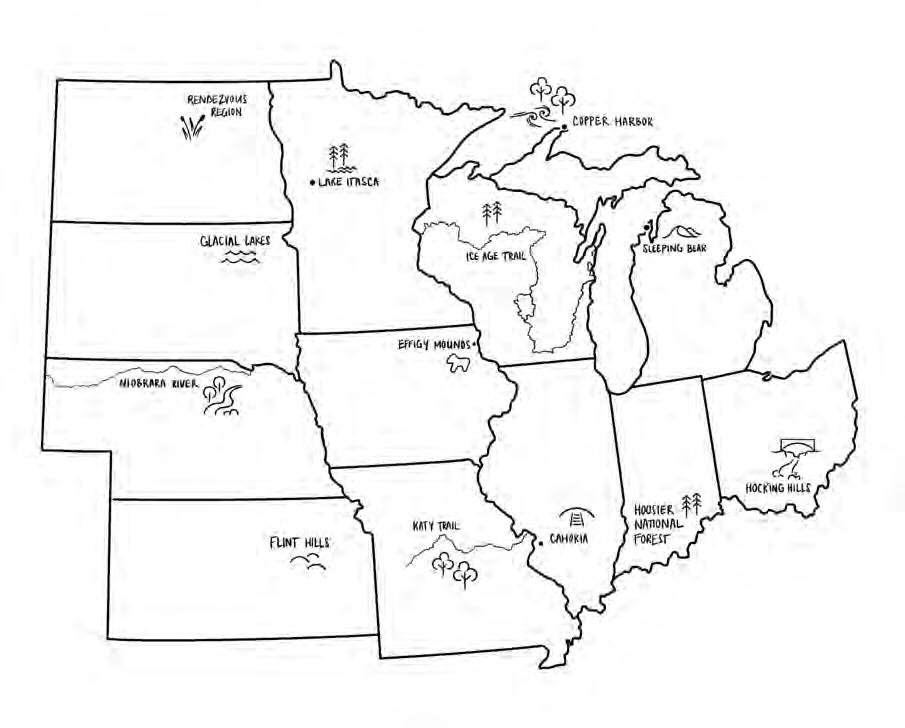

Finally, this book is neither a tourism manual nor a book about the twelve best-known places in the Midwest. Were it that, there would be chapters about Six Flags over St. Louis, the Wisconsin Dells, the Ozarks of Missouri, and Mt. Rushmore of South Dakota. Nothing against those places, but this work seeks to take you places that you may not have heard of or given much thought to. The regions highlighted here may offer readers—even midwesterners themselves—a few notes of surprise.

Who knew that Wisconsin is home to an eleven-hundred-mile national scenic trail, the Ice Age Trail, that roughly follows the end moraine of the last glacier, separating the ice-leveled north from the rugged hills of the unglaciated Driftless Area?

Who knew that Michigan’s sixteen-hundred-mile sand-drifted shoreline along Lakes Superior and Michigan is a remnant of the even larger lakes that existed at the height of the glacial melt back? Or that copper mines once ruled Michigan from depths as far as fourteen hundred feet below ground?

Those who have driven across Indiana and Ohio’s interstates have witnessed vast agricultural resources on the Plains. But southern Ohio first d imples and then rises and plunges in a region called the Hocking Hills, festooned with box canyon waterfalls. Nearby lies a coal-mining past in the Appalachian foothills in one direction and the birthplace of the Hopewell culture of mound-building Native Americans in the other.

Southern Indiana’s Hoosier National Forest fans out across two hundred thousand acres of hilly land reforested by the federal government after early farming erosion and the Great Depression brought about widespread farm foreclosures. This is karst country, too: east of the forest lie great cave networks channeled into the subsurface limestone.

It may come as no surprise that Kansas is grass country, but who knew that eastern Kansas is home to 80 percent of the nation’s remaining tallgrass prairie? The prairie there is preserved because the hilly, rocky terrain of the Flint Hills made the land too rugged to plow. So ranchers graze cattle on the nutrient-rich native grasses.

I advise drivers crossing Nebraska on Interstate 80 to detour to the northernmost tier of counties to the Niobrara River, which downcuts through a two-hundred-foot canyon graced with numerous waterfalls. You will pass through the haunting sandhills along the way.

I may live along and be partial to the Mississippi River, but the Missouri River is its chief North American rival. Bicyclists love the Katy Trail that follows along the river valley halfway across the state of Missouri. History is layered here as the trail runs on the bed of the historic Missouri-Kansas-Texas (or MKT, or Katy) Railroad. And layered beneath that is t he pathway of Meriwether Lewis and William Clark and their Corps of Discovery as they ascended to the West and returned to St. Louis on the Missouri River.

Natural, Native American, and early pioneer history layers the Mississippi River shoreline along western Illinois from East Dubuque to the Ohio River confluence. The Native American city of Cahokia grew to a population of twenty thousand around AD 1100. Cahokia was the seat of

the Mississippian culture where the Missouri and Illinois Rivers joined the Mississippi, offering highways to the north, south, east, and west. Location, location, location.

The North Dakota landscape may look unpeopled, but the northeast corner was once called the Rendezvous Region, where French fur traders and Native Americans came together annually to transport beaver fur and bison hides across the landscape to eastern seaboard and European markets. The flatland that once sat at the floor of Glacial Lake Agassiz is now the vast and frequently flooded plain of the north-flowing Red River. But the Pembina escarpment rises sharply and surprisingly from this plain, leading to a more rugged terrain to the west.

The eastern corridor of South Dakota defies outsiders’ perceptions of the state. South Dakota evokes images of eastern plains and the haunting terrain of the western Badlands, Black Hills, and Mount Rushmore. But northeast South Dakota is a lake-filled area called the Glacial Lakes and Prairies Region, and the southeast corner surprises with its orange-pink quartzite arising out of the landscape only to be sliced by downcutting rivers.

The long story of the Mississippi River begins with a small stream emerging from Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota. The infant river wants to flow quietly north, which it does for a while until the Laurentian and St. Lawrence Divides redirect it southward, sending it on a journey that bisects the country and gathers to it the great rivers, so that in the end the Mississippi watershed drains 40 percent of the United States. Nineteenth-century explorers paddled through the North Country making claims and counterclaims as to the source of the great river. But how does one decide which flow leads to the headwaters and which ones are tributaries? The local Ojibwe were bemused by the quest. Didn’t all of its flows contribute to the Father of Waters?

The Mississippi River runs beneath the bluffs of my home in Dubuque, Iowa. While relatively little of Iowa’s land fits the prevailing mental construct of the state as flat, northeast Iowa in particular shatters the common perception. Steep hills and valleys, rock towers, caves, and freshwater springs pop from every turn along our winding roads in Iowa’s corner of the Driftless Area, or what geologists call the Paleozoic Plateau. This was sacred land, a refugium to plants, animals, and humans sheltering from the great ice to the north. In this refugium, Native Americans built twohundred-foot-long burial and ceremonial mounds, many shaped as bears and birds, on the bluffs overlooking the Mississippi. Here in the northeast corner of the state, Effigy Mounds National Monument protects the largest cluster of effigy, conical, and linear mounds in the country.

Eleven of the twelve Midwest state names derive from Native American words or tribal names, however distilled, mangled, and misunderstood by European and American interpreters. And so we have: Illinois, from Illiniwok, simply meaning “men” but misapplied by Europeans as a name for regional tribes; Iowa comes from the Ioway tribe; Kansas is from the Kansa people, also known as the Kaw; and Missouri is from the tribal name meaning the “canoe-havers.” In relation to natural features: Michigan comes from an Algonquin word meaning “big lake”; Minnesota arose from a Dakota word meaning “cloudy water” or “sky-tinted water,” depending on the pronunciation; Ohio comes from the Iroquois word meaning “beautiful river”; Wisconsin is from the French interpretation of a name for the state’s largest river, the “Ouisconsing”; and Nebraska is close to the indigenous name for the Platte River, ni braska . North and South Dakota derive from a term meaning “friends” or “allies.” The one Midwest state whose name, ironically, isn’t derived from an indigenous word—Indiana—is an American-English reference to the Land of the Indians in general.3

An introduction is a bit early to debate the ethics of Euro-Americans adopting indigenous place names while simultaneously purging indigenous peoples from those same lands. One side will argue that Whites remembered the Native American past by so naming their states and landmarks, while another side sees the practice as whitewashing history. Yet a third view offers that regardless of the reasons and motivations, if Euro-American founders had not so-named their states, there would have been even more erasure of the Native American past from the landscape. For the moment, though, let’s entertain some different state configurations for the Midwest. I’ll name them here for their landscape regions to show that the Midwest is more diverse in its physical geography than most would suspect. My objection to the current twelve state boundaries is that they are political creations often unrelated to the landforms on which they sit. I’ll leave it up to you whether or not to give these new states indigenous names. The Midwest states redrawn according to seven landforms would be:

• Northern Glacial Plain: This state would run across the northern Midwest, including the upper halves of Wisconsin, Minnesota, and north-central Iowa. This is not the only region to have been leveled or otherwise impacted by the most recent (Wisconsinan) glacier, but the glacier’s effects are particularly visible on the landscape here in the forms of kettle ponds, drumlins, eskers, and moraines. Much of North and South Dakota would fit here, too, but I’m putting them into different states. You can see the problem already.

• Tallgrass Prairie: This might be the largest of the Midwest states, running north-south through eastern North and South Dakota, east Nebraska, and east Kansas, and then plunging eastward through Iowa, northern Missouri, north-central Illinois, and a bit of northwest Indiana. Here, big bluestem once grew taller than a rider on horseback, and wildflowers bloomed and waved throughout the summer. Very little tallgrass prairie survives: its rich prairie soil has largely been utilized for farmland.

• S hortgrass Prairie: This state would parallel the western flank of the Tallgrass Prairie state from north to south, but its drier conditions would be noticeable in the smaller height and different variety of grasses. These lands today are either irrigated for agricultural use or grazed as cattle ranches. The Shortgrass Prairie state, while relatively level to the local eye, would nonetheless commence an upward slope to the Rocky Mountains. The western halves of North and South Dakota, Nebraska, and Kansas would make up the Shortgrass Prairie state.

• The Great Lakes Perimeter: This state would outline Lakes Superior, Michigan, Huron, and Erie, a narrow and sinewy region snaking the lakes’ shoreline through Minnesota, Michigan, Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio. This thin band along the lakes has a landscape all its own, having been the former bed and shoreline of the postglacial lakes.

• E astern Woodlands: The Eastern Woodlands state comprised of north and central Indiana and Ohio would blend at its edges with the Northeast state of Pennsylvania. Perhaps the definition of Midwest would again be under contention.

• Southern Hills: This east-west state would run across the southern flanks of Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, and Missouri. This is a rugged, hilly, and forested region that lies beyond the farthest reach of the glaciers.

• The Driftless: The Driftless region encompasses twenty thousand square miles covering the corners of four midwestern states: northwest Illinois, northeast Iowa, southeast Minnesota, and southwest and central Wisconsin. Its ancient hilly and rocky landscapes were neither bulldozed nor plowed under by the glaciers. Its soils contain little or no glacial drift from the Wisconsinan period glacier—glacial drift meaning anything dragged along with, dropped by, or blown in from the massive ice, hence “Driftless.” This is my state. Viroqua, Wisconsin, already claims to be its capital.

I’ll be the first to admit that these boundaries overlap, and that there could be other and different configurations. Perhaps it would have to be settled by political means nevertheless.

But imagine identifying with one’s landscape instead of lines drawn arbitrarily across a map.

Imagine identifying as midwestern.

1 Wisconsin

The Ice Age Trail: Landscape Tells a Story

St. Croix Dalles at Interstate Park (Mile 1)

They might have been gigantic witches’ brew pots painstakingly ground into the bedrock. The smaller ones could have been mixing bowls and the tiny ones inverted cups for sipping rainwater with a straw.

But geologists call them potholes, circular indentations in the bedrock formed when roaring glacial meltwater on the St. Croix River drained the long-gone Glacial Lake Duluth. The meltwaters burst through a sandstone and basalt lip in the landscape, creating Taylor Falls and a hundred-footdeep gorge called the St. Croix Dalles in its roaring wake. Potholes formed when rounded stones—as big as bowling balls and as small as marbles— spun dizzily in the eddying currents and downcut perfectly circular holes into the bedrock. Some of the larger potholes were as deep as six feet and as wide as twelve.1

The Wisconsin Ice Age Trail was not yet on my mind years ago when I first pulled into Interstate Park on the Wisconsin-Minnesota border to wander amid this curious landscape. Bisected by the St. Croix River, the park resides on both states’ rocky shoreline boundary. Winter snowmelt

had set the falls roiling and the St. Croix spraying and tossing from one side of the rock-walled gorge to the other. It was an annual, miniaturized replay of the end of the glacial period twelve thousand years ago.

On a bluff overlooking the St. Croix River, as it settles out downstream from the falls, sits another boulder, this one embossed with a plaque announcing the western terminus of the Wisconsin Ice Age Trail. For those w illing and able to devote their time and legs, the Ice Age Trail here begins a 1,150-mile trek across Wisconsin, following the approximate edge of t he last glacier’s advance. Stretching roughly from northwest to southeast and north again across the state, the trail separates Wisconsin’s glaciated regions to the north from the unglaciated “Driftless” region to the south. A transitional washout zone from the edge of the melting ice occasionally buffers the two landscapes.

Landscape always tells a story. The grayish-black basalt here at Interstate Park—so different from the Midwest’s prevailing limestones, sandstones, and shales—formed from lava flows erupting along fault lines a billion years ago. Half a billion years later, the basalt lay beneath a shallow sea as the North American continental plate slid slowly across the equator. The sea compacted a thick sandstone across the basalt, and eventually the region drifted north and uplifted. Repeated ice ages buried the land under glaciers beginning two million years ago, followed by intermittent thaws. Just twelve thousand years ago, a blip in geologic time, the last great glacier was melting in full force.

I was hiking on the Pothole Trail, two hundred feet downstream from where the meltwater torrents ripped through, creating the Falls, Dalles, and potholes, and scattering ten-foot-high angular blocks of basalt around the gorge. The Pothole Trail is perched high above the St. Croix, indicating that the engorged river ran one hundred feet deeper during the deluge than it does today.2

It was a long time ago. I’m referring of course to the lava flows, ancient seas, and glacial melt, but also to my visit to Interstate Park. I was traveling alone, researching another writing project. My wife and older son back home had just picked out a used car for his teenaged needs. They were consulting with me on my first cellphone as I picked along the trail.

I might as well have been wandering amid the dinosaurs, it was so long ago. My son is in his thirties now, and my flip-phone long ago disappeared into another watery tumult: our family’s washing machine.

But the stories are still here in the landscape. And the great ice still seems only a grinding crunch away.

The Wisconsinan Ice Age

Do you hear it coming? The snap of a tree trunk in its path, the cracking of bedrock underneath, the groan of ice crawling in the valley just beyond the bend? You would have to listen and watch for centuries and let yourself be numbed to the bone, of course, but the wall of ice is on the move, ever so slowly.3

What set off the great beasts from the North? The earth’s tilt cycles every forty-one thousand years between twenty-two and twenty-five degrees off vertical, and when the tilt is greatest, the North Pole will be farther away from the sun in winter. Winter deepens. The earth wobbles like a top through space, and every twenty-two thousand years completes a cycle that likewise puts the North Pole farther away from the sun. Winter deepens. The earth’s orbit around the sun cycles between elliptical and nearly c ircular paths, and when the extreme elliptical path puts us farther away from the sun for long stretches of the year, winter deepens.4

When all three cycles align and conspire, the ice may awaken in the North.

Why not in the South? A perhaps not-so-obvious requirement for continental glaciers is the presence of continents. The Southern Hemisphere hasn’t experienced widespread glaciers except, of course, on Antarctica itself because there are no other large land masses near enough to the South Pole for glaciers to crawl across.

The Wisconsinan period of glaciation had merely been the latest, beginning one hundred thousand years ago. Twelve thousand years ago, it w as in full retreat.

Earlier glacial advances had also covered North America. The Illinoian glaciers conquered the upper Midwest 300,000–130,000 years ago, outlining, as the name suggests, the present-day shape of Illinois. Pre-Illinoian glaciers—sometimes divided into Nebraskan and Kansan—blanketed the northern states even earlier, up to 2.5 million years ago. All of the midwestern states were touched by at least one of the glacial periods.

But only the most recent glacial period is still prominently written on the landscape. Its impact was unmistakable. The Wisconsinan glacier was six hundred feet thick near its edge, but was more than two miles deep farther back over present-day Hudson Bay. Evidence of its movement and melting is still apparent.

The Wisconsinan glacial period also impacted human habitation in North America. So much of the earth’s water was tied up in the ice that sea levels fell four hundred feet, opening up a land path from Asia to Alaska

(a swath that remained fortuitously unglaciated) that humans followed in their incessant wanderlust. Many lingered at the glacier’s edge, hunting mastodons and wooly mammoths until these megafauna suffered perhaps the first human-induced extinctions. Others dispersed throughout North and South America, the ancestors of Native Americans, the first immigrants to the New World.

The ice in my driveway that winter seemed solid as a stone at the curb where I’d given up trying to chop it down to the concrete. The ice on my roof seemed immobile, till during a slight thaw it let loose and pulled the gutter down with it.

How, then, on a flat plain, does ice begin to crawl?

When snow survives the summer melt, as it did when the world grew colder and winter grew longer, it compacts into ice beneath the next year’s snow, which in turn compacts during the following summer’s partial melt. At a hundred-foot depth, after centuries of accumulation, the ice begins to flow like a heated plastic, at first molding itself to the contours of the land, but then—as it gains weight, depth, and force—gouging, scraping, and bulldozing the land as it moves. In one place, the ice might crawl along at a few meters per year, somewhere else one or two kilometers. At its final reach, where summer melt offsets the push of new ice, the glacier’s edge doesn’t move at all, but the ice behind still presses forth. Stalemate.

The Wisconsinan glacial period saw numerous retreats and advances. Twenty thousand years ago, it began its final assault. The earth’s annual average temperature dropped by six degrees Celsius. At the center of the continental glacier, the average temperatures plunged by twenty degrees.

The ice pressed southward through Canada and the northern United States, as well as northern Europe and Asia, often in adjacent lobes that competed for the ground they covered. In Wisconsin, the Superior and Chippewa lobes covered the northwest corner of the state. The Wisconsin Valley and Langlade lobes fronted the north-central regions. The Green Bay and Lake Michigan lobes swallowed the east and southeast. Q

Can you calculate a tipping point? When did the summer grow warm enough and the winter less intense so that the ice groaned to a halt and began its slow retreat? About twenty thousand years ago, the glacier had reached its full extent and started its retreat.

But was it on a Tuesday in April?