List of Acronyms

ACICR International Committee of the Red Cross Archive

AFRHA US Airforce Historical Research Agency

AFS Swiss Federal Archives

AGSSt Armee Gefangenen sammelstelle (Army Prisoner Collection Point)

ANZAC Australian and New Zealand Army Corps

ARC American Red Cross

AWA Allgemeines Wehrmachtsamt (the OKW’s General Office)

BA Bundesarchiv

BA-MA Bundesarchiv-Militärarchiv

BRC British Red Cross

Btn Battalion

CHAR The Churchill Archive

COS Chiefs of Staff

FRUS Foreign Relations of the United States

HSSPF Höherer SS- und Polizeiführer (Higher SS and Police Leaders)

ICRC International Committee of the Red Cross

IDF Israel Defence Force Archive

IMT International Military Tribunal

IWM Imperial War Museum Archive

JC Jewish Chronicle

JISC Joint Intelligence Sub Committee

JMM Jewish Military Museum Archive

JTA Jewish Telegraphic Agency

LMA London Metropolitan Archive

Ln Location

MOC Man of Confidence

NARA National Archives and Record Administration

NCO Non-Commissioned Officer

NSDAP Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (the Nazi Party)

NSFO Nationalsozialistischer Führungsoffizier (National Socialist Leadership Officers programme)

OKH Oberkommando des Heeres (Army High Command)

OKW Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (Armed Forces High Command)

OR Other Ranks (i.e. not officers or NCOs)

PAAA Politisches Archiv des Auswärtigen Amt

PMA Prague Military Archive

POW Prisoner of War

RAF Royal Air Force

RSHA Reichssicherheitshauptamt (Reich Security Main Office)

RSM Regimental Sergeant Major

SA Sturmabteilung (Storm Detachment)

SAO Senior American Officer

SBO Senior British Officer

SD Sicherheitsdienst (Security Services)

SS Schutzstaffel (Protection Squad)

TNA The National Archives

USHMM US Holocaust Memorial Museum Archive

WJC World Jewish Congress

YVA Yad Vashem Archive

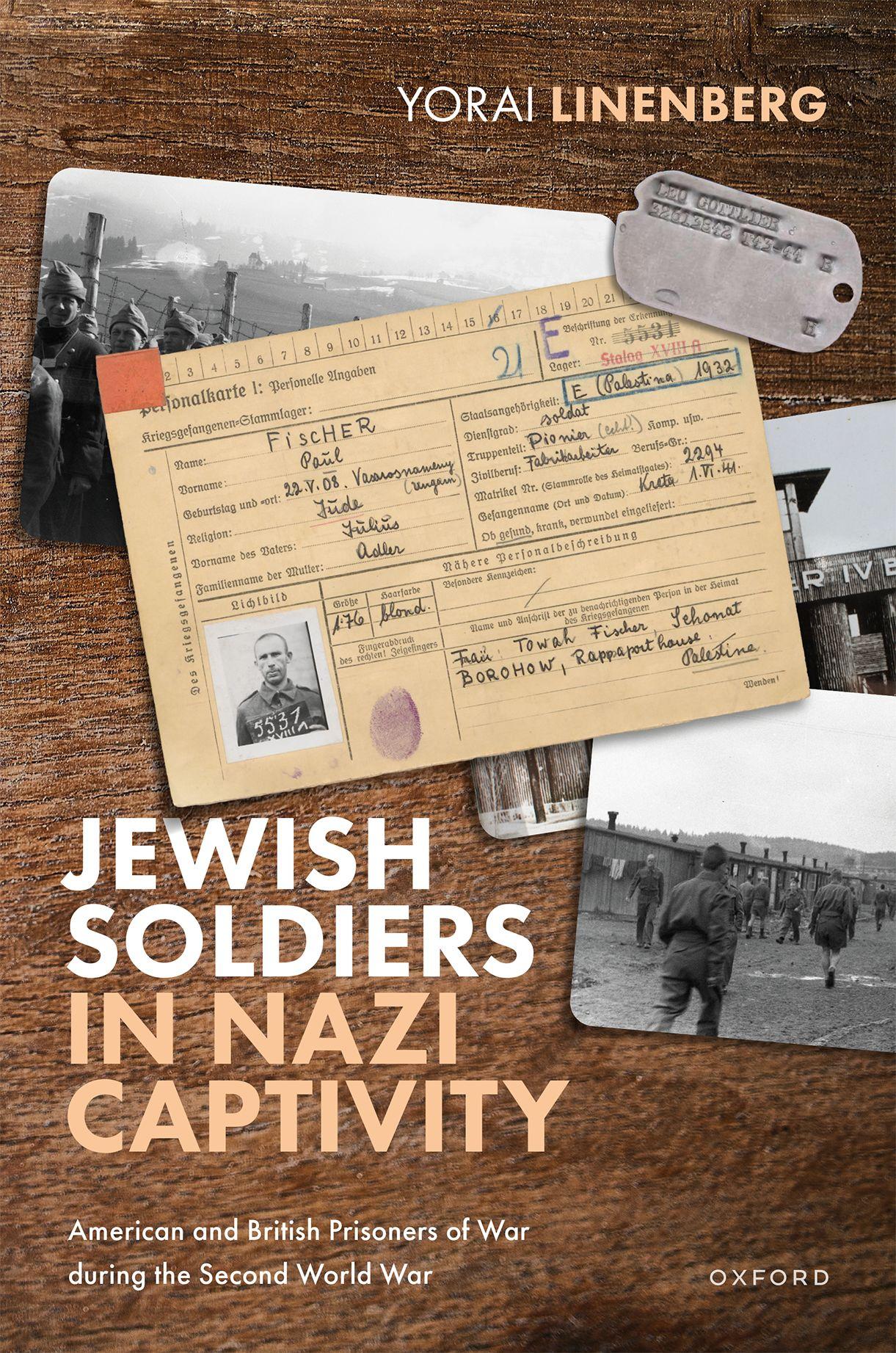

Introduction

As I got nearer to the desks I could hear the questions being asked of the men in front of me . . . when it came to religion, lying seemed the safe thing to do. I hadn’t heard [any other POW] admit to being Jewish. But I didn’t care. In my mind I said, ‘F**k you!’ I was young, angry, and by any measure stupid. I answered, ‘Jewish’.1

This is how Milton Feldman, a 19-year-old American infantry soldier who fought with the 106th division and was captured in December 1944 in the Ardennes, described his interrogation upon arrival in Stalag IV-B near Mühlberg in Germany. Since Nazi ideology considered Jews to be a separate ‘race’, which it defined as a group with heritable social and cultural characteristics that were ‘innate, indelible, and unchangeable’, and in view of what was already known by that stage of the war about Germany’s murderous policies against Jews, Feldman’s concern—although not his eventual reaction—was well founded.2 Polish Jewish Prisoners of War (POWs) were segregated upon capture and mistreated; Yugoslavian Jewish POWs were in some cases shot after their surrender by their Croatian ex-brothers-in-arms; French Jewish POWs were segregated in POW camps from their non-Jewish comrades; and the Einsatzgruppen, with the Wehrmacht’s cooperation, combed POW camps immediately after the invasion of

1 Milton Feldman and Seth Bauer, Captured, Frozen, Starved—and Lucky: How One Jewish American GI Survived a Nazi Stalag (Kindle Edition: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2018), ln. 588.

2 George M. Fredrickson, Racism: A Short History (Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2015), p. 5. Throughout this book, the term ‘race’ is used in the meaning attributed to it at the time by the Nazis, i.e. as a biological category. This ‘theory’ was disproved during the second half of the twentieth century, when the concept of race as a social, not scientific, construct became dominant. Judaism today is usually defined as an ethnic, cultural, and religious identity rather than a racial one (for a discussion regarding the components of the Jewish identity see Chapter 2 of this book). For discussions around the evolution of the concept of ‘race’ and racism throughout history see, for example, Charles Hirschman, ‘The Origins and Demise of the Concept of Race’, Population and Development Review, 30:3 (2004), pp. 385–415; and Fredrickson, Racism: A Short History. An example of the changes in the general attitude towards the term ‘race’ can also be found in the differences between the 1929 Geneva Convention relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War and its newer version from 1949: while Article 9 of the 1929 Convention allowed—in fact, encouraged—the Detaining Power to segregate POWs according to their race, the 1949 Convention disallowed any discrimination based on ‘race, nationality, religious belief or political opinions’. The question of race, it was explained, was left outside the Convention due to the ‘derogatory implication’ of that term (see Timothy L. Schroer, ‘The Emergence and Early Demise of Codified Racial Segregation of Prisoners of War under the Geneva Conventions of 1929 and 1949’, Journal of the History of International Law, 15:1 (2013), pp. 53–76, and esp. p. 74).

Jewish Soldiers in Nazi Captivity: American and British Prisoners of War during the Second World War. Yorai Linenberg, Oxford University Press. © Yorai Linenberg 2023. DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780198892786.003.0001

the Soviet Union in order to select and execute Soviet commissars and Jewish POWs.3 In parallel, Germany’s racial and POW policies had gone through a radicalization process throughout the war, and the Reich Security Main Office—the Reichssicherheitshauptamt (RSHA)—kept pressuring to extend the ‘Special Treatment’ (‘Sonderbehandlung’) of Soviet Jewish POWs to all Jewish POWs held by Germany.4

However, when it came to American and British Jewish POWs, this research will demonstrate that cases of their discrimination and mistreatment were not as common, and they were treated, with very few exceptions, according to the 1929 Geneva Convention relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War (the Geneva Convention). To put this in context, this was the same country that had breached the Treaty of Versailles, violated the Munich Agreement, and flouted the MolotovRibbentrop Pact; that starved to death and murdered millions of Soviet POWs; and whose ingrained anti-Semitism and extreme racial policies eventually led to the Holocaust.5 And yet, in the case of American and British Jewish POWs—in fact, in the case of most non-Soviet Jewish POWs—Germany had decided to stick to its international commitments and to treat them in most cases in the same way their non-Jewish brothers-in-arms had been treated. The significance of this conclusion is that it challenges the accepted perception of the Final Solution as Germany’s indiscriminate attempt during the Second World War to murder ‘every last Jew in Europe upon whom they could lay their hands’.6 Among the reasons

3 For Polish Jewish POWs, see Shmuel Krakowski, ‘The Fate of Jewish Prisoners of War in the September 1939 Campaign’, Yad Vashem Studies, 12 (1977), pp. 297–333, pp. 299–300; Jewish Telegraphic Agency (JTA), 17 November 1939, 27 October 1940, and 28 January 1941, https://www. jta.org/archive, accessed 8 May 2019. For Yugoslav and French Jewish POWs see ICRC to American Red Cross, 24 April 1941, ACICR BG 25/34, and JTA, 18 November 1941, https://www.jta.org/archive, accessed 8 May 2019; German Foreign Office representative in Belgrade to Berlin, 26 November 1941, PAAA R40960; Zvi Asaria-Helfgot, We Are Witnesses (Tel Aviv: Yavne, 1970), p. 32; Testimony of Vladimir Mautner, YVA O.3–6645 p. 19; Irit Keynan, Memories from a Life I Have Not Lived (Tel Aviv: Pardes, 2020), p. 431; Yves Durand, La Captivité (Paris: Fédération Nationale des Combattants Prisonniers de Guerre et Combattants d’Algérie, Tunisie, Maroc, 1980), p. 354; Le Combattant Volontaire Juif 1939–1945 (Paris: Imprimerie Abexpress, 1971), pp. 44 and 64. For the RSHA actions in the Soviet Union see Richtlinien für die in die Stalags und Dulags abzustellenden Kommandos des Chefs der Sicherheitspolizei und des SD, 17 July 1941, BA R58/9016; Christian Streit, ‘The German Army and the Policies of Genocide’, in Gerhard Hirschfeld, ed., The Policies of Genocide, Jews and Soviet Prisoners of War in Nazi Germany (New York and Abingdon: Routledge, 2015), pp. 1–14, p. 4; and Raul Hilberg, The Destruction of the European Jews, vol. I (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2003), pp. 346–53. See also JTA, 9 February 1942, 28 September 1942, and 8 April 1943, https://www.jta.org/archive, accessed 8 May 2019.

4 Letter from Theodor Krafft, 10 August 1951, BA-MA MSG 2/12656.

5 The Nazi approach to its legal obligations was made clear by Goebbels in a press conference held on 5 April 1940, where he declared publicly that ‘. our apparent loyalty to legalistic concepts was simply a smokescreen’ (quoted in Hans-Adolf Jacobsen, ‘The Kommissarbefehl and Mass Execution of Soviet Russian Prisoners of War’, in Martin Broszat, Hans Buchheim, Hans-Adolf Jacobsen, and Helmut Krausnick, eds, Anatomy of the SS State (Cambridge: Walker and Company, 1968), pp. 505–35, p. 507).

6 Christopher Browning, ‘The Nazi Decision to Commit Mass Murder: Three Interpretations’, German Studies Review, 17:3 (1994), pp. 473–81, p. 473.

explaining this was the behaviour of the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht’s (OKW) POW Office, which, unlike other organizations in the Reich and despite the pressure exerted on it by the RSHA, refused to ‘work towards the Führer’ in anticipating his will and in implementing Nazi policies without receiving specific orders to do so.7

This book explores the story of American and British Jewish POWs from two points of view: first, it will look at the experiences that American and British Jewish POWs had in German POW camps throughout their captivity lifecycle, and investigate the reasons why their immediate captors—including commandants, camp guards, and civilians who worked with the POWs—treated them the way they did; it will then address the question of how American and British Jewish POWs dealt with their Jewish identity throughout their captivity period. The second point of view will look at the bodies above the POW camps: it will review the reasons the orders to segregate Jewish POWs in POW camps from their non-Jewish comrades were not always followed in the case of the American and British Jewish POWs; and will look at explanations for why these POWs (and in fact, Jewish POWs from all western armies) were treated, in most cases, according to the Geneva Convention, despite the German obsession with applying ‘The Final Solution for the Jewish Question’ to all Jews in occupied Europe.

POWs in German Hands—the Numbers

The Second World War broke out on 1 September 1939 with the German invasion of Poland. By the end of the Polish campaign, approximately 450,000 Polish officers and other ranks were taken into German captivity.8 By June 1940, the German victories in Western Europe resulted an additional 2.2 million soldiers becoming POWs of Germany. The largest group among them was that of the French, which numbered approximately 1.9 million (of which about 980,000 remained in Germany by the end of the war as a result of repatriations and escapes).9 Belgian POWs numbered 225,000, although the Flemish among them,

7 Ian Kershaw defines ‘Working towards the Führer’—a term coined in 1934 by Werner Willikens, German state secretary in the ministry of food—as ‘anticipation of Hitler’s presumed wishes and intentions as “guidelines for action” in the certainty of approval and confirmation for actions which accorded with those wishes and intentions’ (see Ian Kershaw, ‘ “Working Towards the Führer.” Reflections on the Nature of the Hitler Dictatorship’, Contemporary European History, 2:2 (1993), pp. 103–18, pp. 116–17). Christopher Browning described how ‘rival Nazi chieftains constantly sought to expand their private empires and vied for Hitler’s favour through anticipating and pursuing Hitler’s desires’ (see Christopher Browning, Fateful Months (New York and London: Holmes & Meier, 1991), p. 16); and General Franz Halder, the army’s chief-of-staff until September 1942, described how Hitler’s casual remarks could bring his subordinates to give a ‘factual expression to the will of the Führer’ (see Jacobsen, ‘The Kommissarbefehl and Mass Execution of Soviet Russian Prisoners of War’, p. 516).

8 The estimates of the number Polish POWs vary. For a discussion about their numbers see Bob Moore, Prisoners of War (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2022), p. 28 and especially n. 7.

9 Moore, Prisoners of War, pp. 61 and 87.

about half of the total, along with most of the soldiers from Norway and the Netherlands were released in the weeks and months after the end of the campaign.10 POWs from the British Expeditionary Force in France—most of which was evacuated through Dunkirk—numbered approximately 40,000.11

In April 1941, Germany invaded Yugoslavia and Greece in order to secure its southern flank ahead of its invasion of the Soviet Union and to bail Italy out of its disastrous campaign in Greece. 350,000 Yugoslavian soldiers became POWs; by the summer of 1942, 130,000 of them, mostly Serbs, remained in German captivity, and the rest were released.12 The Greek army surrendered on 23 April 1941, and all of its soldiers—with the exception of those who fought in Crete, whom the Germans claimed had been involved in mistreatment of German POWs—were freed from captivity by the end of May 1941.13 About 11,000 Allied soldiers who participated in the Greek campaign—mostly British but also soldiers from Australia, New Zealand, India, Cyprus, and Palestine—were also taken into German captivity.14

The German invasion of the Soviet Union, in June 1941, resulted in the largest number of POWs from any one country taken into captivity. Between 1941 and 1945, it is estimated that between 5.35 and 5.75 million Soviet soldiers had become POWs.15 The brutal treatment of these POWs, who Germany claimed were not entitled to the protection of the Geneva Convention, resulted in the deaths, by the end of the war, from executions, starvation, diseases, and cold, of 2.5–3.3 million POWs.16

10 For the number of Belgian POWs see ibid., pp. 100–2; for the release of the Flemish POWs see War Journal of Franz Halder (English ed.), Document N-16845-B, Library section, Fort Leavenworth, KS, 28 May 1940, vol. 4, p. 40; for Norwegian POWs see Hitler’s decree, 9 May 1940, in Martin Moll, Führer-Erlasse 1939–1945 (Hamburg: Nikol Verlag, 2011), pp. 118–19; for the Dutch POWs see Rüdiger Overmans, ‘Die Kriegsgefangenenpolitik des Deutschen Reichs 1939 bis 1945’, in Jörg Echternkamp, ed., Das Deutsche Reich und der Zweite Weltkrieg, Band 9/2 (Munich: Deutsche VerlagsAnstalt, 2005), pp. 729–875, p. 756, and Hitler’s decree, 1 June 1940, Moll, Führer-Erlasse 1939–1945, p. 122.

11 Simon MacKenzie, The Colditz Myth (New York: Oxford University Press, 2004), p. 66; and Hugh Sebag-Montefiore, Dunkirk, Fight to the Last Man (London: Penguin, 2007), p. 538. The total number quoted by Sebag-Montefiore, 41,338, comprises missing in action as well as POWs.

12 Overmans, ‘Die Kriegsgefangenenpolitik des Deutschen Reichs 1939 bis 1945’, p. 782.

13 Moore, Prisoners of War, p. 287.

14 Ibid., p. 306. MacKenzie’s estimate was 12,000 (see MacKenzie, The Colditz Myth, p. 77).

15 Overmans, ‘Die Kriegsgefangenenpolitik des Deutschen Reichs 1939 bis 1945’, p. 820.

16 Overmans estimated the number of Soviet POWs who died in German captivity to be between 2.55–3.45 million (Overmans, ‘Die Kriegsgefangenenpolitik des Deutschen Reichs 1939 bis 1945’, p. 820); Alfred Streim’s estimate is 2.545 million (Alfred Streim, Sowjetische Gefangene in Hitlers Vernichtungskrieg (Heidelberg: C. F. Müller Juristische Verlag, 1982), p. 178); the estimates of HansAdolf Jacobsen and Christian Streit are 3.3 million deaths (see Jacobsen, ‘The Kommissarbefehl and Mass Execution of Soviet Russian Prisoners of War’, p. 531; Christian Streit, Keine Kameraden (Stuttgart: Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, 1978), pp. 244–6). For an analysis of the causes of the mass deaths of Soviet POWs see Christian Hartmann, Wehrmacht im Ostkrieg (Munich: R. Oldenbourg Verlag, 2009), pp. 586–608.

The campaigns in the West between 1942 and the end of the war in 1945—the Strategic Air campaign and the campaigns in North Africa, Italy, and Normandy— resulted in approximately 150,000 British—bringing their total number to about 200,000—and 95,000 Americans falling into German hands.17 These included Allied POWs held in Italian POW camps, which, after Italy’s surrender to the Allies in September 1943, were transferred to German hands. Over 600,000 of Italy’s own soldiers—those who refused to continue and fight on Germany’s side—were also taken into German captivity; initially designated as ‘Italian Military Internees’ (IMI), and later as civilian workers, they were not considered POWs and did not come under the protection of the Geneva Convention.18

It is estimated that towards the end of the war, more than 2 million Allied soldiers were still being held as POWs by Germany. The largest group was that of the Soviet POWs; the stark contrast between their treatment and the treatment of non-Soviet POWs has been attributed mainly to the National Socialist racial policies which considered the Slavs to be an inferior race. Whereas the Geneva Convention was generally adhered to when it came to non-Soviet POWs, the war in the East was launched as a war of extermination (‘Vernichtungskrieg’), which meant that both sides left their own POWs to their fate.19

In total, approximately 200,000 Jewish soldiers were captured by Germany and its European allies during the Second World War. The majority of them were Soviet (85,000), Polish (60,000–65,000) and French Jews (55,000); and although exact numbers are not available, it can be assumed that there were also several hundred Jewish POWs from Yugoslavia, The Netherlands, Belgium, and probably less from Canada, South Africa, Australia, and New Zealand.20

This research focuses mainly on the experience of Jewish POWs from the USA and Britain. The reasons for this specific focus are both the availability of primary and secondary sources that describe their experience, in comparison to Jewish POWs from other nationalities; and the reciprocity factor, which, since the USA and Britain (along with Canada) were the only western countries holding large numbers of German POWs, contributed to some extent to the treatment of their POWs in accordance with the Geneva Convention.

17 Aryeh Kochavi, Confronting Captivity (Chapel Hill and London: University of North Carolina Press, 2005), p. 1.

18 Overmans, ‘Die Kriegsgefangenenpolitik des Deutschen Reichs 1939 bis 1945’, pp. 829 and 835.

19 Overmans, ‘Die Kriegsgefangenenpolitik des Deutschen Reichs 1939 bis 1945’, p. 871.

20 Shmuel Krakowski, ‘Jewish Prisoners of War’, in Israel Gutman, ed., Encyclopedia of the Holocaust (Tel Aviv: Hakibutz HaMe’uchad, 1990), pp. 1180–1; Mark Spoerer, ‘Die soziale Differenzierung der ausländischen Zivilarbeiter, Kriegsgefangenen und Häftlinge im Deutschen Reich’, in Jörg Echternkamp, ed., Das Deutsche Reich und der Zweite Weltkrieg, Band 9/2 (Munich, 2005), pp. 485–576, p. 505. Many Jewish Polish POWs, along with other categories of Polish POWs, were released from captivity between October 1939 and March 1940 due to the overcrowding of the POW camps (the remaining POWs were converted to civilian labour); the release of the Jewish POWs sealed, in effect, their fate as most of them were sent later to the concentration camps (see Overmans, ‘Die Kriegsgefangenenpolitik des Deutschen Reichs 1939 bis 1945’, pp. 745–7).

The total number of Jews in the British army during the Second World War, including the Jewish volunteers from Palestine, was approximately 95,000, and they accounted for 1.6% of the total number of British servicemen and women.21 The number of British Jewish POWs in German captivity is estimated at 2,200, of whom approximately 700 came from the different arms of the British armed forces.22 The remainder, approximately 1,500, were Jews from mandate Palestine who volunteered for the British army and served mainly in the Royal Pioneer Corps, where they formed the majority in some of the companies that were captured by the Wehrmacht in Greece in April 1941. Interestingly, more than 1,000 of them were Jewish refugees who had immigrated—some of them illegally—to Palestine from Europe in the years before the war as a result of Nazi oppression.23

On the American side, statistics compiled by the United States National Jewish Welfare Board estimate that there were approximately 550,000 Jews in the different branches of the United States’ armed forces (3.4% of the total) during the Second World War, and 3,700 of them became POWs.24 Unlike the British statistics, no breakdown between the European and Pacific theatres is available for them; however, by applying the ratio between the number of American POWs in German captivity and the total number of American POWs (approximately 95,000 out of 143,000), it can be estimated that about 2,500 American Jews were held as POWs by Germany.25

Although the total number of approximately 4,700 American and British Jewish POWs, which constituted about 1.6% of the total number of American and British POWs in German captivity, is only an estimate, and the actual numbers are probably slightly different, it is still sufficiently accurate for the purpose of this study. The records and testimonies related to these Jewish POWs provide broad insights into the German Jewish POW policies, the experience and treatment of Jewish POWs in German captivity, the level of Nazification and antiSemitism within the Wehrmacht and specifically in its POW organization, and the level of the Wehrmacht’s compliance with the 1929 Geneva Convention.

21 Henry Moriss and Martin Sugarman, We Will Remember Them (Portland, OR and London: Vallentine Mitchell, 2011), pp. 3–4.

22 Ibid., pp. 340–53.

23 Simon to Majerozik, 16 April 1943, CZA S-25\4720. The letter stated that only 400 (out of 1,500–1,600) Palestinian Jewish POWs had relatives in Palestine.

24 Louis Dublin and Samuel Kohs, American Jews in World War II, vol. 2 (New York: The Dial Press, 1947), pp. 22 and 27. According to the US Department of Veterans Affairs, the total number of service members in the Second World War was 16.1 million (see Department of Veterans Affairs publication, November 2020, https://www.va.gov/opa/publications/factsheets/fs_americas_wars.pdf, accessed 1 April 2021).

25 World War II prisoners of war data file, NARA, https://aad.archives.gov/aad/series-description. jsp?s=644&cat=GP24&bc=,sl, accessed 26 May 2023.

Historiographic Review

The literature covering POWs in German captivity in the Second World War is extensive; and the Nazi attempt to implement a ‘Final Solution to the Jewish Question’ and the resulting Holocaust form together a major field in the studies of twentieth-century history.26 However, the converging point of these two fields—the research on Jewish POWs in German captivity during the Second World War—has not received the same level of attention. One reason for this gap might be that most studies of the POW experience were based on the nationality of the POWs, rather than their religion or ethnicity; another reason is that, with few exceptions, the treatment of Jewish POWs, whether on the Eastern or Western Fronts, was similar to the treatment given to their non-Jewish comrades: that is, leading to an almost certain death for Jewish POWs in the East, and mostly in line with the Geneva Convention in the West. The contradiction between the Nazi obsession with exterminating the Jews and, when it came to Jewish POWs from the western allies, their almost complete adherence to the Geneva Convention was in fact mirrored in the regulations issued by the POW Office: on one hand, an order that was issued towards the end of the war by the then-head of the POW Office, SS General Gottlob Berger, informed POW camp commandants that ‘. . . Jewish prisoners of war are to be treated like the other prisoners of war belonging to the respective armed forces’; and on the other, an order that was issued in 1942 and instructed camp commandants not to accept blood donations from POWs since ‘it cannot be ruled out with certainty that even partJews [jüdische Mischlinge] among the prisoners of war will be used as blood donors’.27

The experience of Jewish POWs in German captivity has only been covered in very few studies and mostly comes to light in memoirs and collections of testimonies of individual POWs. This can be partly attributed to the fact that, on the Eastern Front, very few Jewish POWs survived the war, since their fate was determined by the Commissar Order; and in the West, to the fact that American POWs had to sign, after their release, an affidavit prohibiting them from discussing their experience.28 Another contributing factor was that, with the exception of Palestinian Jews who fought as a group in the British army, Jews were fully

26 It is not possible to list all the studies on the Holocaust; however, the important ones include Raul Hilberg’s The Destruction of the European Jews (first published in 1961) and Saul Friedländer’s Nazi Germany and the Jews: The Years of Extermination: 1939–1945 (2007).

27 Befehlsammlung 48, order 876, 15 December 1944, and Befehlsammlung 15, order 111, 10 August 1942, BA-MA RW 6/270.

28 According to Raul Hilberg, only 6,000 Soviet Jewish soldiers came back from German captivity (Hilberg, The Destruction of the European Jews, vol. III, p. 1319n). For American Jewish POWs see Jeff Donaldson, Men of Honor—American GIs in the Jewish Holocaust (Central Point, OR: Hellgate Press, 2005), p. ix; and Gerald Daub, oral history, recorded 6 July 2000, Archive of the Museum of Jewish Heritage, New York.

integrated in the units they belonged to, whether on the battlefield or in POW camps, and did not always see their captivity experience as being very different to that of their non-Jewish comrades. The tendency of the belligerents during the first decade after the war to focus on their own suffering, which meant that Jewish war veterans and Holocaust survivors kept their experiences largely to themselves, can also explain the limited number of memoirs and testimonies.

The story of the Jews who fought in the Soviet and Polish armies—although outside the scope of this research—sheds light on the vast difference between their fate and the fate of those who fought for the western allies. Not many studies on this specific topic have been conducted: Raul Hilberg devoted eight pages to it in The Destruction of the European Jews (first published in 1961), describing how the Einsatzgruppen combed POW camps where Soviet POWs were held, throughout Europe and the occupied parts of the Soviet Union, looking for Bolsheviks and Jews, and then executed them.29 Szymon Datner’s early study of Crimes against POWs—Responsibility of the Wehrmacht (1964) which was published in Poland, is based mainly on the International Military Tribunal (IMT) protocols of the Nuremberg trials and includes a section that deals with Jewish POWs, describing the harsh treatment suffered by Polish and Soviet Jews.30 The access to Soviet archives in the 1990s provided sources for further studies: Pavel Polian, in his article ‘First Victims of the Holocaust: Soviet-Jewish Prisoners of War in German Captivity’ (2005), used these sources to review the subject of Soviet POWs in general, before moving on to describe the specific fate of the Jews among them; and Aron Shneyer, in his book Pariahs among Pariahs (first published in 2005), describes in great detail the experience of Soviet Jewish soldiers in German captivity, beginning with an overview of Jews in the Russian—later Soviet—army and the anti-Semitism they had encountered. Given that very few Soviet Jewish soldiers managed to survive both the appalling conditions of German captivity and the extermination of the Soviet Jewish POWs, Shneyer’s ability to find and interview those who survived, combined with his detailed research of primary sources, is impressive. Shmuel Krakowski’s article ‘The Fate of Jewish Prisoners of War in the September 1939 Campaign’ (1977) is based mainly on personal testimonies and memoirs of Polish Jewish and non-Jewish POWs and describes the fate of Polish Jewish soldiers who fought in the Polish campaign in September 1939 and became POWs. Polish POWs were in general badly treated by the Germans, but the Jews among them—with the exception of the officers—suffered an even worse treatment, not least because of the antiSemitism of the Polish POWs themselves. The number of Polish Jewish POWs who survived the war is difficult to estimate; most of those who were released in

29 Hilberg, The Destruction of the European Jews, vol. I, pp. 346–53.

30 Szymon Datner, Crimes against POWs: Responsibility of the Wehrmacht (Warsaw: Zachodnia Agencja Prasowa, 1964), pp. 98–109.

the months following the end of the Polish campaign were murdered later, together with their families, in the concentration and extermination camps.

Analysing this topic from the German side, The Policies of Genocide: Jews and Soviet Prisoners of War in Nazi Germany, edited by Gerhard Hirschfeld (1986), provides a collection of essays that links the treatment of Soviet POWs to the extermination of the Jews. In the first article in this collection, ‘The German Army and the Policies of Genocide’, Christian Streit argues that the turning point in the German policy against the Jews from a territorial solution to extermination came with the invasion of the Soviet Union. He describes how General Hermann Reinecke, the head of the OKW’s General Office (Allgemeines Wehrmachtsamt, or AWA), allowed Reinhard Heydrich, the head of the RSHA, only a few days after the start of the invasion of the Soviet Union, to send his Einsatzgruppen units to select and execute Soviet Commissars and Jewish POWs.31 This shift—from the execution of only political enemies (the commissars) to racial ones (Jewish POWs)—might indeed be considered as the watershed point; however, for reasons that will be discussed in Chapter 4 of this book, these orders were eventually not extended to non-Soviet Jewish POWs.

On the general subject of German treatment of Jewish POWs both in the West and in the East, Rüdiger Overmans’s article, ‘German Treatment of Jewish Prisoners of War in the Second World War’ (2016), provides a high level overview of the experience of Jewish POWs from all Allied armies (including French, Yugoslav, Polish, etc.) in German captivity and highlights the differences in treatment between Soviet Jewish and non-Soviet Jewish POWs. Overmans explains that the almost-fair treatment received by the latter group can be attributed mainly to the principle of reciprocity—the German concern that mistreatment of western POWs would lead to reprisals against German POWs held by the western Allies.32 However, this principle, which was used in multiple studies to explain the treatment of non-Soviet POW in general, has several inconsistencies and is discussed below in more detail.33

With regards to the specific topic of American and British Jewish POWs in German captivity, there are only a limited number of studies. One of these studies is of special relevance—Yoav Gelber’s article ‘Palestinian POWs in German

31 Christian Streit, ‘The German Army and the Policies of Genocide’, in Gerhard Hirschfeld, ed., The Policies of Genocide, Jews and Soviet Prisoners of War in Nazi Germany (New York and Abingdon: Routledge, 2015).

32 Rüdiger Overmans, ‘German Treatment of Jewish Prisoners of War in the Second World War’, in Anne-Marie Pathé and Fabien Théofilakis, eds, Wartime Captivity in the 20th Century (New York and Oxford: Berghahn, 2016), lns 1240–60.

33 For other studies that suggested the reciprocity argument see Kochavi, Confronting Captivity, p. 195; Streit, Keine Kameraden, p. 70; Aron Shneyer, Pariahs among Pariahs (Jerusalem: Yad Vashem, 2016), p. 82; and David Killingray, ‘Africans and African Americans in Enemy Hands’, in Bob Moore and Kent Fedorowich, eds, Prisoners of War and Their Captors in World War II (Oxford: Berg, 1996), pp. 181–204, p. 199.

Captivity’ (1981), which describes the experience of approximately 1,500 Palestinian Jews who volunteered to fight in the British army and were taken captive together in Greece in 1941. These POWs went mostly as one group through the same captivity lifecycle as their non-Jewish British brothers-in-arms. Gelber relied on British, German and Israeli archives, along with memoirs written by the Palestinian Jewish POWs, to construct a chronological account of events from their capture, through their experience during the captivity period, to the forced marches across Germany at the end of the war and their liberation in April and May 1945. Gelber’s conclusion was that, in general, the Palestinian Jewish POWs were treated in a similar way to their non-Jewish comrades; however, the article does not provide an explanation as to why they were treated in that way. In addition, since the Palestinian Jewish POWs were mostly treated as a separate national group, similar to the way POWs from other British dominions were treated, their experience was different to that of individual American and British Jewish POWs. Both groups are dealt with separately in this book.

Bob Moore dedicates one chapter in his book Prisoners of War—Europe: 1939–1956 (2022) to Jewish POWs, focusing on the experience of Jewish POWs from Poland, Yugoslavia, France, Belgium, and the Soviet Union. One section deals with the fate of Jewish POWs from Britain and the USA, and brings several examples of their treatment and their experience in POW camps; however, the chapter does not deal with the reasons for the different treatment of non-Soviet Jewish POWs and Soviet Jewish ones.

Other studies on the topic of American and British Jewish POWs include Martin Sugarman’s article ‘Two Notes on Jews on Active Service’ (2004), which lists the Jewish POWs who passed through the POW camp at Colditz Castle—as well as those he had reason to believe were Jewish, but decided not to reveal their ethnicity—and provides a short description of the whereabouts of some of them; and one chapter in Russell Wallis’s book British POWs and the Holocaust: Witnessing the Nazi Atrocities (2017), which describes the relationship between British Jewish and non-Jewish POWs. Wallis argues that even though the British POWs grew up in a liberal society and were not exposed to a totalitarian one, they were still able to recognize the German hierarchy of victims, in which the Jews came last; however, the treatment of the Jews evoked responses in the POWs that ranged from empathy and compassion on one hand all the way to indifference and anti-Semitism on the other. Other parts of Wallis’s book provide detailed accounts of interactions between British (including Jewish) POWs and civilian Jews, victims of the Holocaust; a few of these interactions occurred in concentration camps, where some British POWs found themselves, usually when they were captured after taking part in a commando operation or after they were caught by the Gestapo following an escape attempt. For POWs, being incarcerated in a concentration camp was especially risky because it usually meant that they were no

longer considered POWs and therefore were outside the protection of the Geneva Convention.

The story of the Berga slave labour camp, to where about eighty American Jewish and 270 non-Jewish POWs were sent from Stalag IX-B in Bad Orb, was actually an exception to the way most Jewish POWs from the West were treated. In his book Soldiers and Slaves (2006), Roger Cohen explains that Berga was selected to be the site of an underground jet-fuel production factory and the local SS authorities, who were in charge both of building the factory and, at this stage of the war, of POW camps, apparently decided to use American POWs in the construction work; however, no direct order to do so, or to specifically select Jewish POWs, has ever been found and many of the selected American cohort were also non-Jewish.34 In addition to Cohen’s book, the story is also described in Mitchell Bard’s Forgotten Victims (1994) and in Flint Whitlock’s Given Up for Dead: American GI’s in the Nazi Concentration Camp at Berga (2005). These books describe the POWs’ time in Bad Orb and the events in February 1945, when the Jewish POWs were segregated, in the face of loud protests led by the camp’s Man of Confidence (MOC—the POWs’ representative) and other POW leaders, from their non-Jewish colleagues, and sent a few weeks later (together with non-Jewish POWs, probably in order to fill a quota) to work in Berga.35 There was no segregation in the Berga camp itself and all POWs were treated in the same way. The death rate in Berga—around 20%—was the highest of all European prison camps where British and American POWs were held.36

Both the Nazification process of the Wehrmacht and its interaction with various bodies of the German state are important in analysing the extent to which the Wehrmacht—from its senior generals down to its soldiers—was willing to adopt and implement Nazi policies and racial doctrines, and, in the case of POWs, apply them to the Jews among them. Wolfram Wette’s The Wehrmacht: History, Myth and Reality (first published in 2002), Rolf-Dieter Müller’s Hitler’s Wehrmacht (2016) and Bryce Sait’s The Indoctrination of the Wehrmacht (2019) describe how National Socialist ideology was adopted by the Wehrmacht, from its top level command, through areas such as its pastoring and justice systems, to the officer corps and its soldiers. Earlier works include Robert O’Neill’s The German Army and the Nazi Party (1968) and Klaus-Jurgen Müller’s books Das Heer und Hitler (1969) and The Army, Politics and Society in Germany, 1933–1945: Studies in the Army’s Relation to Nazism (1987); these books provide an insight into the Nazification process, from the Wehrmacht’s adoption in 1934 of the ‘Aryan Clause’, which prohibited Jews from serving in the Wehrmacht and Wehrmacht

34 Roger Cohen, Soldiers and Slaves (New York: Anchor Books, 2005), pp. 9–10.

35 Flint Whitlock, Given Up for Dead (New York: Basic Books, 2006), pp. 120–1. See also Cohen, Soldiers and Slaves, pp. 79–80.

36 Mitchell Bard, Forgotten Victims: The Abandonment of Americans in Hitler’s Camps (Boulder and Oxford: Westview Press, 1994), pp. 102–3.