A Cursed Throne (After The Fall Book

https://ebookmass.com/product/a-cursed-throne-after-the-fallbook-3-d-m-simmons/

ebookmass.com

RAILROADS PAST AND PRESENT

H. Roger GrantandThomas Hoback, editors

Recent titles in the Railroads Past and Present series

Pennsylvania Railroad

Albert J. Churella

Electric Indiana

Carlos Arnaldo Schwantes

SunsetCluster

H. Roger Grant

The RailroadPhotography ofPhilHastings

Tony Reevy

The Station Agentandthe American RailroadExperience

H. Roger Grant

The DieselThat DidIt

Wallace W. Abbey

Crossroads ofa Continent

Peter A. Hansen, Don L. Hofsommer, and Carlos Arnaldo Schwantes

Narrow Gauge in the Tropics

Augustus J. Veenendaal, Jr.

Amtrak, America’s Railroad

Geoffrey H. Doughty, Jeffrey T. Darbee, and Eugene Harmon

The Panama Railroad

Peter Pyne

Last Train to Texas

Fred W. Frailey

Transportation andthe American People

H. Roger Grant

American Steam Locomotives

William L. Withuhn

My Life withTrains

Jim McClellan

The RailroadPhotography ofLucius Beebe andCharles Clegg

Tony Reevy

Chicago Union Station

Fred Ash

John W. Barriger III

H. Roger Grant

Riding the Rails

Robert D. Krebs

Wallace W. Abbey

Scott Lothes and Kevin P. Keefe

BranchLine Empires

Michael Bezilla with Luther Gette

Indianapolis Union andBelt Railroads

Jeffrey Darbee

Railroads andthe American People

H. Roger Grant

Derailedby Bankruptcy

Howard H. Lewis

Electric Interurbans andthe American People

H. Roger Grant

The Iron Roadin the Prairie State

Simon Cordery

The Lake Shore Electric Railway Story

Herbert H. Harwood, Jr. and Robert S. Korach

The RailroadThat Never Was

Herbert H. Harwood, Jr.

This bookis apublication of

INDIANA UNIVERSITY PRESS

Office of Scholarly Publishing

Herman B Wells Library 350

1320 East 10th Street

Bloomington, Indiana 47405 USA

iupress.org

© 2024 by Robert A. Schalla

Allrights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48–1992.

Manufacturedin the UnitedStates ofAmerica

First Printing 2024

Library ofCongress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Schalla, Robert A., author.

Title: Black diamonds from the treasure state : the incredible saga of the Montana, Wyoming & Southern, and Yellowstone park railroads / Robert A. Schalla.

Description: Bloomington, Indiana : Indiana University Press, [2024] | Series: Railroads past and present | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2023029019 (print) | LCCN 2023029020 (ebook) | ISBN 9780253068194 (hardback) | ISBN 9780253068217 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Railroads United States History. | Yellowstone National Park. | Northern Pacific Railway Company History. | Montana, Wyoming & Southern Railroad Company History. | BISAC: TRANSPORTATION / Railroads / History | BUSINESS & ECONOMICS / Corporate & Business History

Classification: LCC HE2751 .S33 2024 (print) | LCC HE2751 (ebook) | DDC 385.0979 dc23/eng/20230824

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2023029019

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2023029020

This bookis dedicatedto the memory ofmygoodfriend

JOHN FREDLUND, whosegrandparents John andFrances Chesarek ownedthe FirstandLastChance Saloon and Boarding House in Bearcreekduring the town’s heyday.

Bibliography

Index

PREFACE

HAVING BEEN CAPTIVATED AT AN EARLY AGE BY A. B. GUTHRIE Jr.’s vision of Montana in his classic The Big Sky, I had the unmistakable good fortune in early 1989 to be offered a job in Billings, Montana. As the old saying goes, “I wasn’t born here, but I came as quick as I could.” Perhaps a year after my arrival, some of my associates and newfound friends insisted that I be exposed to some of the area’s important cultural activities. As a result, one weekend I found myself in the town of Bearcreek, where the main activity appeared to be drinking beer while watching pigs run around an oval racetrack at the local saloon. Having never attended a pig race, I was impressed. Those little guys can really fly when there is food at the other end of the line. But my most lasting impression from my visit to Bearcreek was the discovery that a railroad had once run through the town. At first there seemed to be little evidence of this, but there on the wall of the saloon was a photograph of a coal mine with lines of railcars parked in front. Having been afflicted with a lifelong fascination with railroads, I asked the bartender if the photo had been taken nearby. “Oh, yeah,” he replied, “that’s the Smith Mine, it’s just up the road.” Amazing, I thought, I have to learn more. Having a full-time job distracted me from further investigation for a number of years, but in the summer of 2003, my interest was renewed when I learned that an old engine house just outside the town of Belfry was about to be torn down due to a state highway

project. This discovery prompted a field trip with two friends, and upon my return, I was inspired to begin a search for photographs. Amazingly, I found numerous photos of this little railroad in museums and archives scattered across the country. My search also led me to an excellent article by historian Jon Axline in the Montana Historical Society’s quarterly. Now I was really interested. My first thought was to see if I could assemble enough photos to publish a simple album with just enough text to tie the pictures together. But as I began to delve into the subject, a very interesting story began to emerge—something completely different from what I had expected.

My initial research revealed a somewhat shadowy character variously identified as Frank Hall, F. A. Hall, or possibly even S. A. Hall. Little seemed to be known of this individual except that he was the man credited with building the railroad to Bearcreek. Further digging soon brought Frank A. Hall to life, and he quickly became the focus of my story. My efforts to learn more about him led me from Montana to Milwaukee, Wisconsin; St. Paul, Minnesota; and back. Soon I was digging into the history of a little-known railroad far from Bearcreek on Bozeman Pass where Hall had made his initial foray into the railroad business.

The story of Frank Hall, his life and business dealings exceeded my most sanguine expectations. Along the way I was introduced to a fascinating tableau of notable turn-of-the-century businessmen and eccentric characters. Starting with Yankee Jim George, an itinerant prospector, the story led me to visionary civil engineer Philip M. Gallaher, and from there on to Boston financier Elijah Smith. Two presidents of the Northern Pacific Railway loomed large as well. I now realized this wasn’t going to be a story limited to an insignificant twenty-five-mile-long short line railroad in southern Montana, for its tentacles reached far beyond the Clarks Fork and Bear Creek valleys. There was intrigue, backstabbing, train wrecks, and heroes and villains who unexpectedly emerged from the woodwork. All of this was more than I had expected or could have hoped for. As some might say, “you can’t make this stuff up.” Now I knew that I had a story worth telling.

In the late nineteenth century, railroads played a crucial role in the development of Montana’s economy. Beginning with the chance discovery of coal in 1866, the saga of Frank Hall’s railroad follows early efforts to bring rail transport to both the New World Mining District, near the northeast corner of Yellowstone National Park, and the Red Lodge–Bear Creek Coal Field in south-central Montana. It includes Northern Pacific’s early, unsuccessful efforts to build a railroad through the National Park and then follows the struggles of various privately financed schemes aimed at developing the vast mineral wealth of both these regions.

In 1905, Frank Hall finally succeeded in financing a railroad to the coal fields, but his plan to continue the line up the rugged Clarks Fork Canyon to the National Park ran afoul of Northern Pacific president Howard Elliott. The story of the construction and operation of the Yellowstone Park Railroad and its successor, the Montana, Wyoming & Southern, delves into the motivations and backgrounds of the individuals involved and their ultimate triumphs and failures. The story is historically important because it reveals how a major corporation worked to control and limit competition within what was perceived to be its exclusive sphere of economic interest. Despite enduring years of interference by the Northern Pacific and setbacks attributable to the line’s poor construction and lack of equipment, the management of this short line railroad persevered and maintained a critical transportation link that spurred the development of not only the Bear Creek coal field but also the expansion of agriculture in the upper Clarks Fork Valley. The railroad’s construction also resulted in the creation of three new towns. One of the few privately owned rail lines in the state, it maintained its independence for nearly fifty years. At a time when Montana’s economy depended on black diamonds for its heat and energy, Frank Hall’s little railroad ensured that some of the highestquality coal in state was available to private, commercial, and industrial consumers.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

SIMPLY STATED, THIS STORY WOULD HAVE NOT BEEN WRITTEN without the encouragement and support of Montana historian Jon Axline. At the inception of this project, Jon not only shared his knowledge and photographs but also generously donated all of his research files on the subject to me. He graciously reviewed early drafts of the manuscript and offered numerous helpful suggestions and insights. Although I am not a historian by training, my initial meeting with Jon inspired me to dive deep into my research and fearlessly begin to connect the dots.

The few hours I spent discussing railroad history with Bill and Jan Taylor at their home near Lolo, Montana, probably unbeknownst to them, was immensely important to this project as well. Their practical advice on writing, publishing, and research helped convince me that I could do this.

My good friend Geoffrey Stone willingly waded through several early drafts of the manuscript and offered numerous insights into western history and railroads. His comments, corrections, and advice greatly improved the final product. I am also indebted to Gary Hughes for his assistance in creating the regional maps and to Jo Wiggins for sharing his extensive map database and preparing the detailed map of Belfry. Denver attorney Chris Hayes helped guide me through the arcane technicalities of several legal proceedings, Steve Durrett contributed his insights into corporate finance, and Dave

Bickerstaff contributed much appreciated last-minute help with computer graphics. Thanks must also go out to all the museum personnel and archivists across the country who graciously endured my repeated inquiries and requests. The assistance and guidance received from the editors and staff at Indiana University Press made the publication process a seamless endeavor. Numerous other individuals contributed their support and encouragement in various ways during the several years spent on this project, and I thank you all.

Finally, I must extend my warmest heartfelt thanks to my patient and supportive wife Jeannine, who not only put up with my reclusive and compulsive behavior during my research and writing but also cheerfully read several drafts of the manuscript. Her insights and encouragement helped to bring this project to fruition.

Needless to say, I have done my best to piece together a story that I believe to be true and accurate, but in some cases, I was forced to rely on scattered and disparate bits of information. In the end, I bear full responsibility for any errors of fact, omission, or interpretation.

“Treat Him in Every Way as an Irresponsible Fellow”

ON A BLUSTERY DAY IN LATE JANUARY 1891, FRANK AVERY Hall, a small-time businessman from Milwaukee, Wisconsin, stepped off a train at the Northern Pacific depot in Helena, Montana, and made his way uptown to the New Merchants’ Hotel. Located on Broadway not far from the state capitol building, the recently refurbished New Merchants’ was known for its elegant bar, billiard room, restaurant, and wide hallways carpeted with crimson velvet. One of the swankier establishments in Helena, it was the sort of place where prominent businessmen and politicians gathered to discuss the day’s events over a glass of good whiskey and a fine cigar. For Frank Hall, the upand-coming president of Reliance Wire Works, the hotel’s opulence must have been appealing. A parlor-level room with steam heat and electric lights cost him just $1.25 per night on the European plan; an upgrade to the American plan, with all meals included, added as little as $1.25 more.1

Tall, thin, and clean-shaven with dark, wavy hair, Frank Hall possessed boyish good looks, a flamboyant personality, and wry wit. At age twenty-three, he was brimming with self-confidence and ready to take on the world. Born in New York in 1868, the timing and circumstances of his move to Milwaukee are unknown, but in 1886, at the age of no more than eighteen, he and W. N. Fitzgerald, the son of a well-known local ship inspector, purchased Charles

Goehner’s wire works plant in Racine, Wisconsin. Hall and Fitzgerald changed the company name to Reliance Wire Works and immediately announced plans to invest $10,000 in order to expand operations. Where they got the money for this ambitious venture is unknown, but it suggests they may have come from families of at least modest wealth and had connections to the local business community. The Green Bay Weekly Gazette described Fitzgerald as a “promising young businessman.” Considering his ambitious nature and entrepreneurial flair, this portrayal could, no doubt, have been applied to Frank Hall as well. Said to be well known in the area, both Hall and Fitzgerald were previously associated with the manufacturing concern E. P. Allis & Company, an important employer in Milwaukee that would soon become known worldwide as farm equipment manufacturer Allis-Chalmers.2

A purveyor of fences, vine trainers, office railing, and window guards, Reliance Wire Works did not file Articles of Association with the Wisconsin Secretary of State until March 1887, by which time Hall and Fitzgerald had brought in a third, somewhat older partner, named Oscar F. Lindman. Hall’s trip to Montana four years later was likely prompted by the reluctance of a certain Fred M. Wilson to make good on a $453.85 bill owed to Hall’s company. Hall sued Wilson and eventually won a judgment against him. Whether he ever received payment is unknown; however, the trip west piqued Hall’s interest in the Treasure State, and he would soon return.3

With one plant operating in Racine, in late 1892 Hall changed the company name to Reliance Wire and Iron Works and in a bold move acquired the Beloit Architectural Works in Beloit, Wisconsin. This expansion added a second plant to his operations but appears to have left Reliance financially overextended. Just a year later, deep in debt, Reliance Wire and Iron was bankrupt, a victim of the Panic of 1893. Reliance Wire’s failure may have been the first time Hall faced financial ruin, but it would not be the last. As the country slipped into a serious economic depression, 1894 found Hall both out of work and out of money. His activities and financial struggles during the next several years are obscure, but he returned to Montana

several times, visiting Butte in 1895 and Helena a year later. Whether he was seeking employment or business opportunities is unknown.4

In November 1897, Hall once again ventured out to the Treasure State. This time as the representative of a Chicago syndicate that hoped to raise $30,000 to underwrite the construction of a rye whiskey distillery. Having developed his skills as both a persuasive and elegant speaker, Hall diligently pursued his sponsors’ goals by making presentations in Billings, Great Falls, and Bozeman. As an enticement, he described how the distillery would provide a muchneeded boost to the local economy while it produced forty barrels of “a splendid brand of rye whiskey” per day. He went on to explain that the plant would benefit local farmers by providing a yearly market for 120,000 bushels of rye. Hall’s arguments were persuasive, but despite his best efforts, he was unable to raise the capital his backers sought and his mission ended in failure. But his activities did not go unnoticed. The Billings Weekly Gazette described him as presenting his proposal in a “very favorable and pleasing light.” For Frank Hall the Gazette’s praise meant little. When he returned to Milwaukee, he was once again out of work and ready to take on whatever might come next.5

Despite his numerous setbacks, the indefatigable Milwaukee salesman and promoter once again headed west to Montana in February 1898, this time to begin work on a highly speculative railroad project. In the late 1890s, promoters were making fortunes in the railroad business, and having become intrigued with the business opportunities in Montana, Hall was anxious to try his hand at this new and potentially lucrative profession. His partners in this new enterprise were Willis A. Ritchie and William Wallace Davenport Turner, two well-respected businessmen from Spokane, Washington. Their plan was to build a one-hundred-mile-long railroad that would cross the Gallatin Valley and then follow the Gallatin River through miles of uninhabited wilderness to a place called Dodge Creek, where Ritchie and Turner believed there was a vast coalfield.6

Ritchie, a thin man with prominent ears that accentuated his narrow face, was a renowned architect who had invested in numerous mining ventures in several western states. Although he had begun his career in Winfield, Kansas, in 1889 he moved to Seattle and relocated to Spokane four years later. During this time, he was responsible for the design of numerous public buildings and county courthouses throughout the state of Washington, one of the more notable being the famous Jefferson County courthouse in Port Townsend. Hall’s other partner, William W. D. Turner, a sturdy-looking man with dark, wavy hair and a bushy mustache was born and raised in Missouri. An attorney by training, Turner had served in the Union army during the Civil War and attained the rank of colonel. When the war ended, he moved to Wisconsin and opened a law office in Ripon, about forty miles northwest of Milwaukee. He served in the state legislature for a time before deciding there was more opportunity out west.

Turner’s move to Spokane proved his instincts were correct, and he soon made a fortune investing in gold and silver mines, most notably the Le Roi mine near Rossland in British Columbia. How Frank Hall, a whiskey distillery promoter and ex-president of a bankrupt wire company, became acquainted with these two prominent Washington businessmen is a mystery. In Turner’s case, there may have been a Wisconsin connection. What that connection might have been is unclear, unless it involved some tie to Hall’s extended family. The fact that Turner departed Wisconsin in 1885, when Hall was a teenager, makes it seem unlikely they would have ever crossed paths. Why Turner and Ritchie took Hall on as their partner is an even greater mystery. Having no prior railroad experience, Hall’s youth and energy might have been enough to impress them. Or perhaps they were swayed by his witty, gregarious personality and persuasive salesman’s charm. Spokane’s SpokesmanReview added to the mystery by describing Hall as “a moneyed man” from Milwaukee, which seems an unlikely appellation given his apparent lack of success in recent business activities. Perhaps Hall portrayed himself as “a moneyed man” to gain Turner and Ritchie’s

trust. If this was the case, they should have looked into his background a little more closely.7

Articles of Incorporation for the Gallatin Railroad Company of Spokane were filed in late February 1898 with William Turner, Willis Ritchie, and Frank Hall listed as officers and Llewellyn A. Luce of Bozeman serving as the firm’s general counsel. The seemingly incongruous name originated from a decision to incorporate the company in Washington State, where the filing fee was a mere $7.75, rather than in Montana, where it would have cost $503. The railroad the partners envisioned was a huge undertaking that would start at Three Forks, Montana, extend eastward across the agricultural lands of the Gallatin Valley, and then follow the Gallatin River south up its narrow, rugged canyon to Dodge Creek (presentday Taylor Fork of the Gallatin). Here Willis Ritchie confidently claimed, “There are some very rich and extensive coal fields . . . which the company has purchased.” He went on to explain, “The coal fields embrace thousands of acres and the road is designed with only one object in view, and that is to provide means of transportation to get our product to the market.” According to Ritchie they had already completed a survey of the proposed route and had interested “a number of eastern capitalists” in the project. The problem with Ritchie’s plan was that the coalfields did not exist. Although a few coal beds were present in the Dodge Creek area, none of them constituted a commercial deposit. Ritchie, it appears, had been grossly misinformed by whoever sold him the property.8

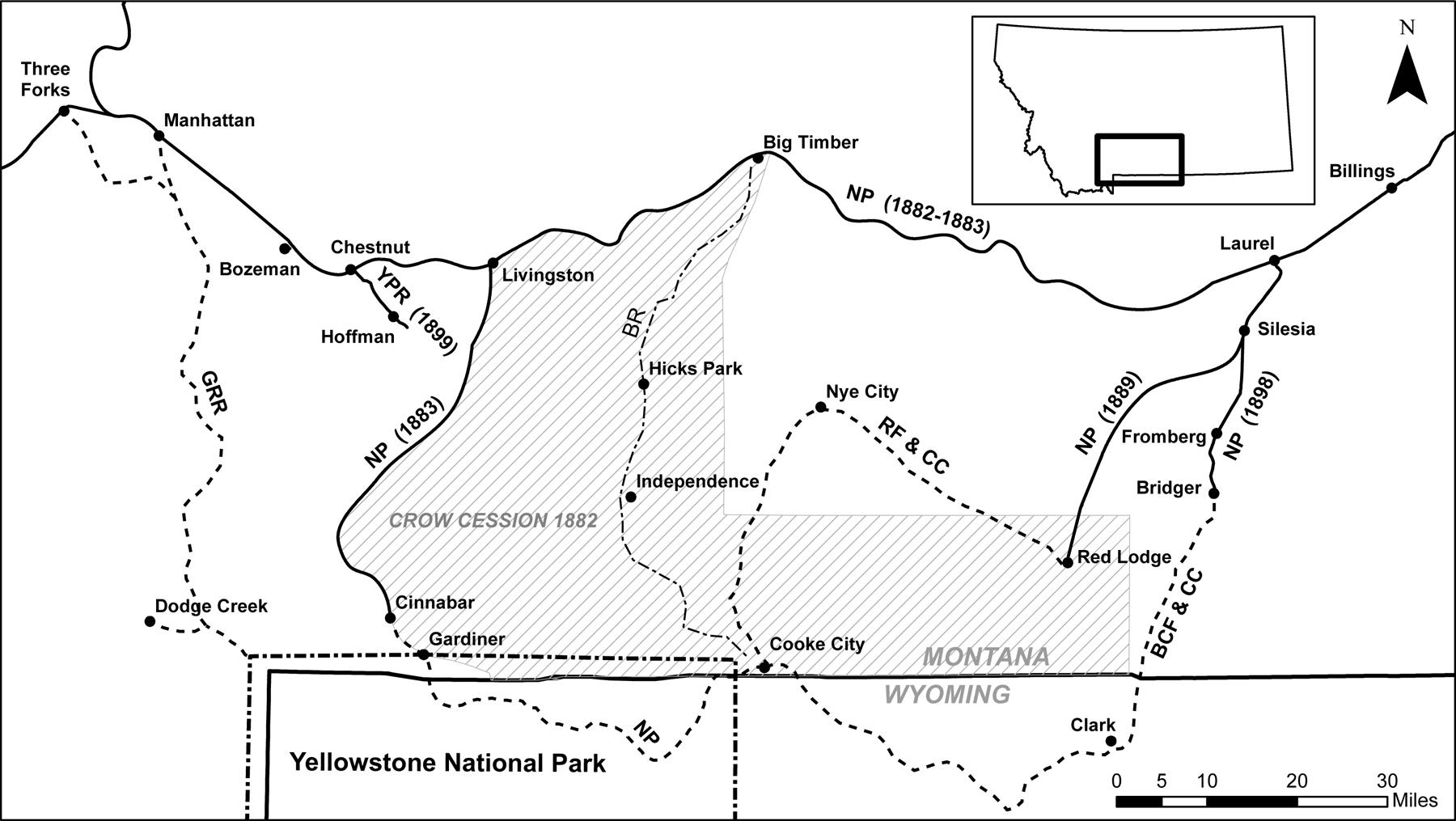

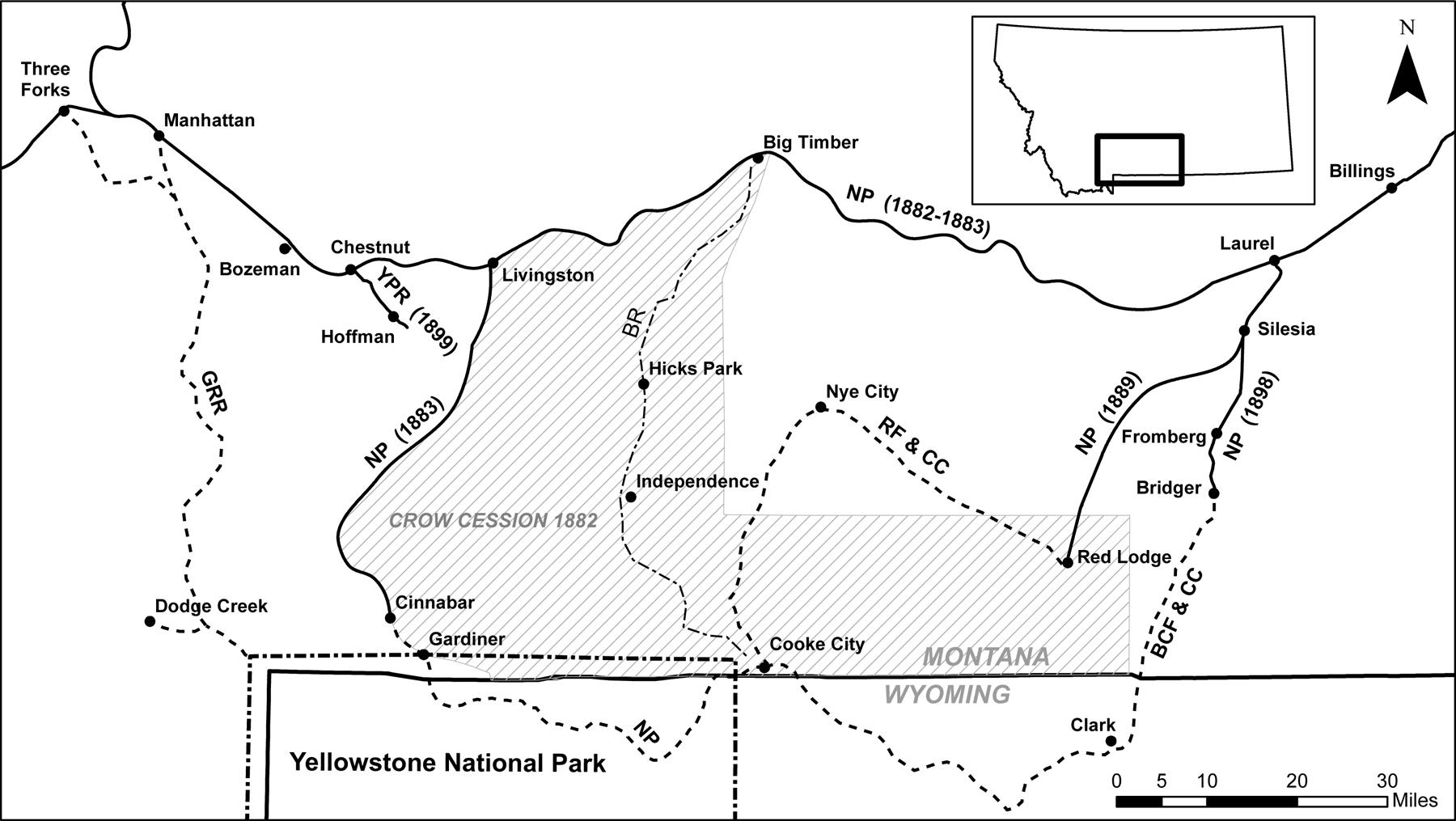

Map of south-central Montana showing the Crow Cession of 1882 and railroad development through 1900. NP (Northern Pacific); YPR (Yellowstone Park Railway); proposed lines: GRR (Gallatin Railroad); RF&CC (Rocky Fork & Cooke City); BCF&CC (Billings, Clark’s Fork & Cooke City); BR (Boulder River route).

Once the incorporation papers were signed, Frank Hall, the company’s vice president and general manager, assumed responsibility for day-to-day operations and moved to Bozeman. But he soon headed east to New York to meet with Ritchie’s “eastern capitalists” and to Washington, DC, to discuss their proposed route with government officials. Upon his return in April, he announced that permission had been granted by the federal government to run their line all the way to Yellowstone National Park, an extension that was probably not part of Willis Ritchie’s original plan. Curiously, at the same time, he made no mention of Ritchie’s supposed East Coast investors. Nevertheless, Hall was enthused about his new venture and was convinced that local farmers would be supportive. His next move was to solicit their help by requesting they donate land for the right-of-way and complete the grading of the roadbed

across their property for free. Sadly for Hall, his appeals for voluntary support fell on deaf ears.9

While Hall was busy trying to garner local support, the project suffered a severe setback when Willis Ritchie, perhaps having received discouraging news from his investors, or possibly more accurate information regarding the coal lands he had purchased, dropped out of the project. William Turner, seemingly unconcerned, promptly replaced him with his younger brother George, an attorney who had recently been elected to the US Senate. An agreement was soon formalized to give Hall and each of the Turner brothers onethird of the company stock. Hall retained his position as vice president and general manager.10

In mid-June 1898, Hall optimistically informed the Anaconda Stavndard that the first fifty miles of the Gallatin Railroad would be completed that summer, enough he said, to bring in most of that year’s wheat crop. Then, in an apparent overreach of his geographic knowledge, he also claimed that when complete the railroad would reach to within three miles of Mammoth Hot Springs. Having likely never visited the area, Hall did not elaborate on exactly how he planned to navigate his way through the several mountain ranges between the Gallatin River and Mammoth. In the end, it was just a lot of fanciful talk, a talent that Hall seems to have cultivated to some great extent during his years as a salesman. As spring passed into summer and the anticipated local support failed to materialize, he came to realize that locals had little interest in a railroad up the Gallatin Valley. When William Turner arrived in Bozeman in late June to meet with Hall, he found him despondent. Although the lack of local support was a major setback, Hall and Turner soon learned that a group of coal mine operators in the Trail Creek area south of Bozeman Pass, having been rebuffed by the Northern Pacific Railway (NP), were anxious to have someone build a railroad to their mines.11

The Livingston Coal Field, of which Trail Creek was a part, had been an important source of fuel for the NP and smelters across Montana since 1883, but by 1898, much of the production was in

decline. Mines near the NP mainline at Timberline had closed in 1895 and operations at Cokedale, near Livingston, were nearing their economic limit. The only remaining mines of any significance were located on the mainline at Chestnut and Mountain Side. But just a few miles to the south, on the hillsides above Meadow and Trail Creeks, thick beds of the same high-quality bituminous coal lay virtually untouched due to the lack of reliable transportation. The group that approached Hall and Turner was led by influential state senator Charles W. Hoffman who saw a great opportunity in the development of these resources. Hoffman’s experience in the area went back many years, having previously operated mines at both Timberline and Chestnut. Being aware of the coal along Trail Creek, as early as 1888 Hoffman had proposed the construction of a railroad to tap those reserves, but ten years later, his vision remained unfulfilled.12

According to the Helena Daily Independent, after meeting with Hoffman, Hall made several trips to the area and “ascertained the nature and extent of its coal,” a considerable achievement for someone with no training in either geology or engineering. With this presumed knowledge, Hall convinced William Turner to return to Bozeman to have a look for himself. Turner, who had a bit more experience evaluating mining properties, liked what he saw, negotiated a tonnage guarantee with Hoffman, and then authorized the start of construction. Although a short branch line to some coal mines was not part of their broader vision for a regional carrier servicing the Gallatin Valley and Yellowstone National Park, the Gallatin Railroad partners seem to have concluded that the Trail Creek branch might be a worthwhile step toward getting their larger venture started. Having made the decision to proceed, Hall excitedly announced on June 28 that they were seeking construction bids and then boldly predicted that trains would be running on what he referred to as the first section of the Gallatin Railroad within ninety days.13

How the partners intended to finance a project with a total cost likely to exceed $100,000 is unknown. But Hall’s initial step was to

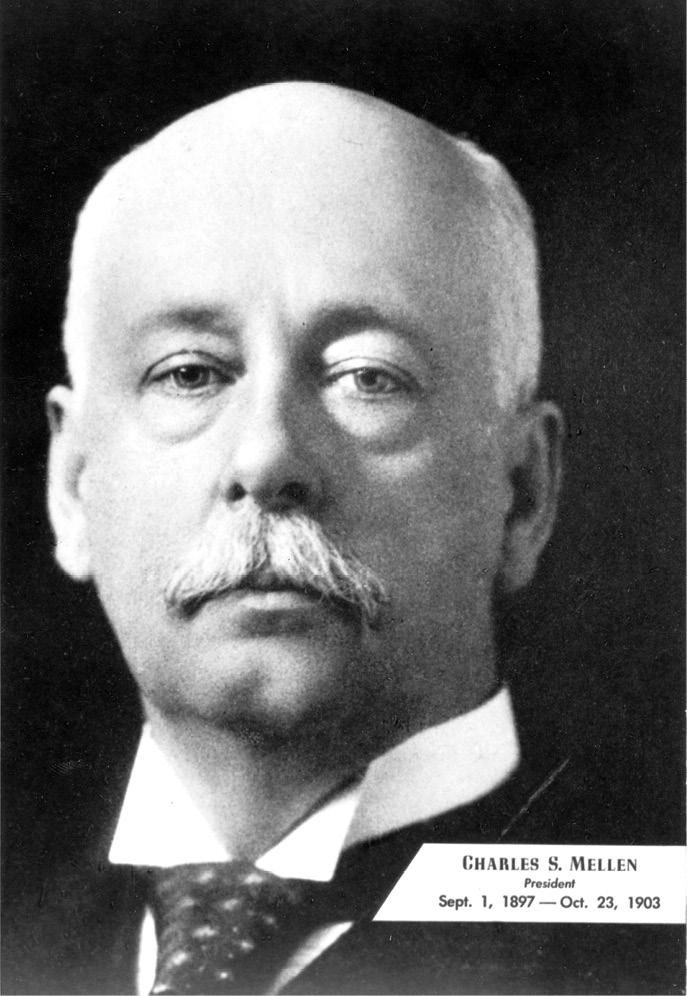

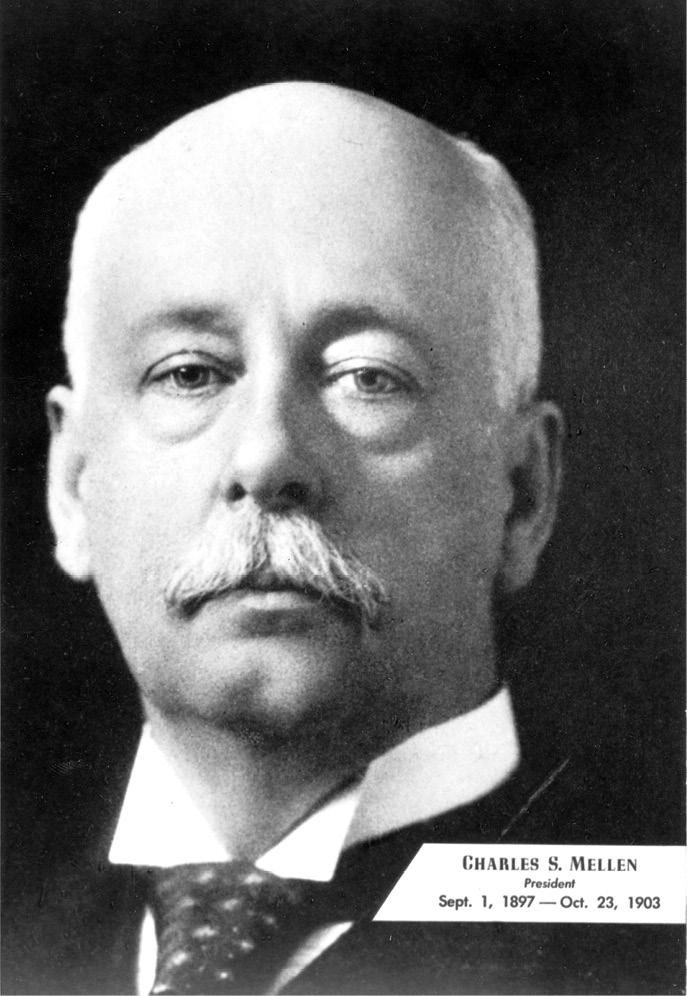

seek the help of the NP, and in July, he traveled to St. Paul, Minnesota, to meet with NP president Charles S. Mellen. A tall, balding man with a prominent chin and commanding presence, the forty-five-year-old Mellen lacked a college education but had nevertheless managed to work his way to the top of his profession. Given his background, it can be imagined that Mellen was somewhat amused when Hall, a dapper, smooth-talking thirty-year-old from Bozeman with no railroad experience, sat down in this office and tried to convince him that the NP should take a mortgage on a yet to be built branch line in Montana.14

Despite Hall’s obvious inexperience in finance, Mellen listened to his proposal with interest and then patiently explained to him not only the legal pitfalls involved in his scheme but also the fact that a mortgage would amount to little more than an unsecured loan, something the NP was not willing to consider. Nonetheless Mellen was intrigued and saw enough benefit in the potential traffic from the Trail Creek mines that he decided to support the project. Because of NP’s tight finances, rather than a cash loan, Mellen offered to supply Hall with construction materials from company stockpiles, the cost of which would be repaid over time. Then, having taken the measure of Hall, Mellen allowed that he was willing to go through with the deal only if Hall could furnish “a note of your Company, endorsed personally by responsible parties.” By this, there is little doubt, he meant the Turner brothers.15

Charles S. Mellen, Northern Pacific Railway president (1897–1903). Mellen’s dealings with Frank Hall left him both frustrated and unimpressed. (Minnesota Historical Society).

The Turners soon agreed to Mellen’s terms, but funding for the remainder of the project remained an issue. Where these funds eventually came from is unknown, but it is likely that the Turners invested their own money and convinced some of their associates in Spokane to buy into the venture as well. Additional funding may have come from Charles Hoffman and the other mine owners. However the money was raised, it was soon clear that contracts were let and work begun before the project was fully funded. Whether this was an oversight or a decision driven by the desire to move forward before winter is unclear. According to one account, the motivation was the tonnage agreement with Hoffman that stipulated a completion date for the line. It could also have been influenced by assurances from Frank Hall that he could easily raise more money