https://ebookmass.com/product/the-fine-art-of-literary-fist-

Instant digital products (PDF, ePub, MOBI) ready for you

Download now and discover formats that fit your needs...

The Fine Art of Literary Fist-Fighting: How a Bunch of Rabble-Rousers, Outsiders, and Ne’er-do-wells Concocted Creative Nonfiction Gutkind

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-fine-art-of-literary-fist-fightinghow-a-bunch-of-rabble-rousers-outsiders-and-neer-do-wells-concoctedcreative-nonfiction-gutkind/ ebookmass.com

Adorno’s Aesthetics as a Literary Theory of Art 1st ed. Edition Mario Farina

https://ebookmass.com/product/adornos-aesthetics-as-a-literary-theoryof-art-1st-ed-edition-mario-farina/

ebookmass.com

The Oxford Handbook Of Plato 2nd Edition Edition Gail Fine

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-oxford-handbook-of-plato-2ndedition-edition-gail-fine/

ebookmass.com

Right Place, Right Time (The Pilsdale Chronicles Book 1) H.L Day

https://ebookmass.com/product/right-place-right-time-the-pilsdalechronicles-book-1-h-l-day/

ebookmass.com

Disorders of Childhood: Development and Psychopathology

3rd Edition Robin Hornik Parritz

https://ebookmass.com/product/disorders-of-childhood-development-andpsychopathology-3rd-edition-robin-hornik-parritz/

ebookmass.com

Peace in the US Republic of Letters, 1840-1900 Sandra M. Gustafson

https://ebookmass.com/product/peace-in-the-us-republic-ofletters-1840-1900-sandra-m-gustafson/

ebookmass.com

Junqueira’s Basic Histology Text and Atlas 14th Edition Anthony L. Mescher

https://ebookmass.com/product/junqueiras-basic-histology-text-andatlas-14th-edition-anthony-l-mescher/

ebookmass.com

Under the Spell of Freedom: Theory of Religion after Hegel and Nietzsche Joas

https://ebookmass.com/product/under-the-spell-of-freedom-theory-ofreligion-after-hegel-and-nietzsche-joas/

ebookmass.com

The Palgrave Handbook of Gender, Sexuality, and Canadian Politics 1st ed. Edition Manon Tremblay

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-palgrave-handbook-of-gendersexuality-and-canadian-politics-1st-ed-edition-manon-tremblay/

ebookmass.com

Neuroanesthesia:

Traul

https://ebookmass.com/product/neuroanesthesia-a-problem-basedlearning-approach-david-e-traul/

ebookmass.com

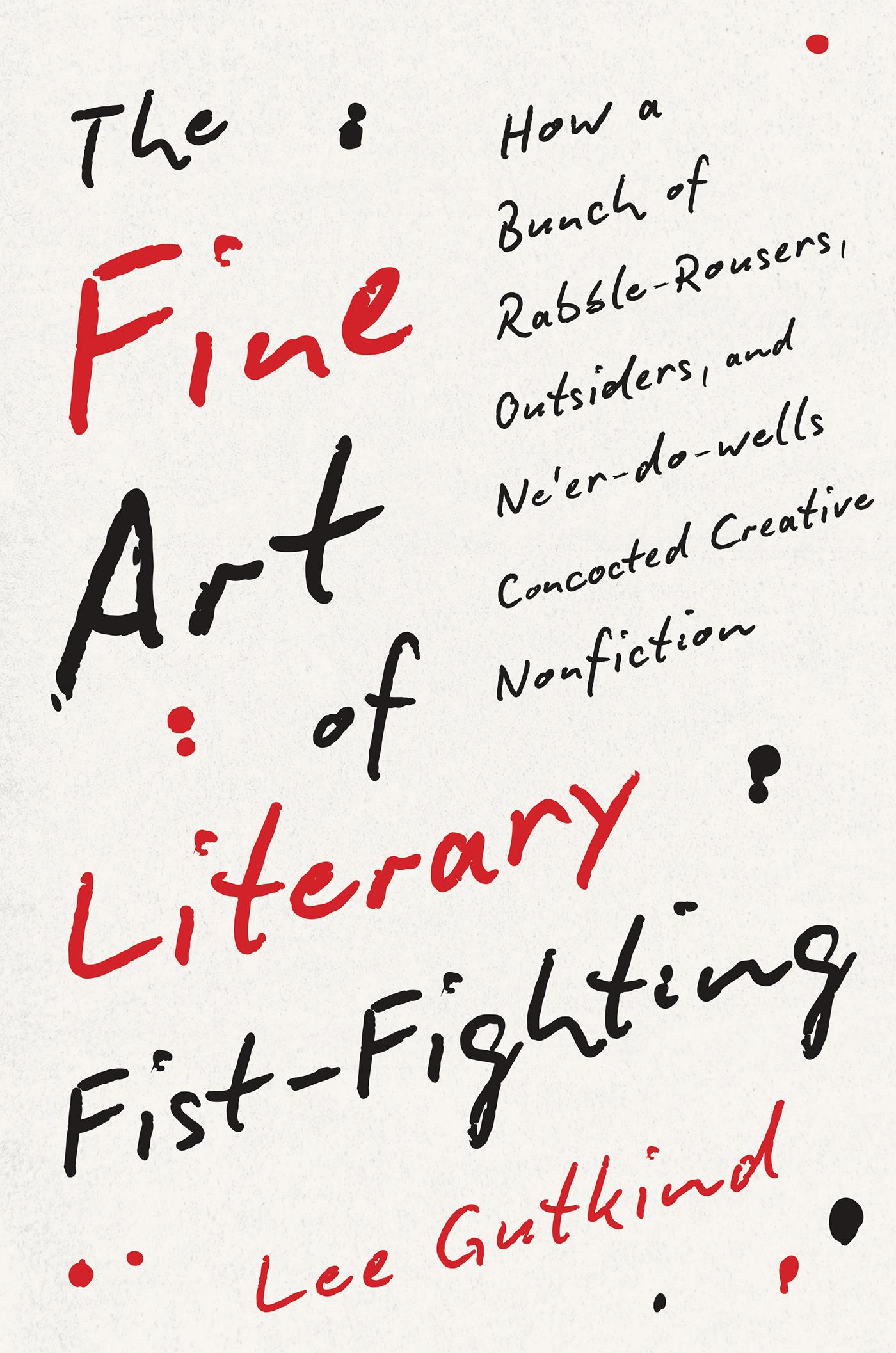

THE FINE ART OF LITERARY FIST-FIGHTING

THE FINE ART OF LITERARY FISTFIGHTING

How a Bunch of Rabble-Rousers, Outsiders, and Ne’er-do-wells Concocted Creative Nonfiction

Lee Gutkind

Copyright © 2024 by Lee Gutkind. All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail sales.press@yale.edu (U.S. office) or sales@yaleup.co.uk (U.K. office).

Set in Yale and Alternate Gothic No2 type by Integrated Publishing Solutions.

ISBN 978-0-300-25115-9 (hardcover : alk. paper)

Library of Congress Control Number: 2023938994

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992(Permanence of Paper).

For Montgomery Culver, with my deepest appreciation for his friendshipand support during my earliest days of dreaming of living the writing life

CONTENTS

Introduction

PART 1

Chapter 1: Who Made This Name Up?

Chapter 2: The Changemakers

Chapter 3: The First Creative Nonfictionists

Chapter 4: A Statue of a Woman in the Pittsburgh Airport and All She Represents

Chapter 5: What White Publishers Won’t Print

Chapter 6: F*** the Establishment

Chapter 7: The Imperfect Primer

PART 2

Chapter 8: The Shoe Dog Goes to College

Chapter 9: A Mentor, a Mountain Man, and the Beginning of the Writing Life

Chapter 10: Innocent Victims

Chapter 11: Manipulating Material—and the People You Are Writing About

Chapter 12: A Larger Reality? Or the Untrue Truth?

Chapter 13: Dissing the Memoir

PART 3

Chapter 14: After All, Gentlemen, We Are Interested in Literature Here—Not Writing

Chapter 15: Bricks, Underwear, Fake Vomit—and a Guinness World Record

Chapter 16: Writers Invading the Academy

Chapter 17: Drama and Trauma

Chapter 18: Mud and Coconuts

PART 4

Chapter 19: How Creative Nonfiction Became CreativeNonfiction

Chapter 20: The First Issue: A Dining Room Disaster

Chapter 21: Do Poets Write Prose?

Chapter 22: The First Creative Nonfiction Conference—and George Plimpton’s Revenge

Chapter 23: The Business of Art? Or the Art of Doing the Art Business

Chapter 24: The Last Creative Nonfiction “Fist-Fight”

Epilogue

Acknowledgments

Notes

Index

THE FINE ART OF LITERARY FIST-FIGHTING

INTRODUCTION

I am often asked: “What is creative nonfiction?” Or, in some cases, “What the hellis creative nonfiction?” The answer—or answers—can be complicated because creative nonfiction may mean different things to different people, a characteristic that makes this form so elusive and alluring.

On its very baseline creative nonfiction is a literary genre. Some people call it the fourth genre, along with poetry, fiction, and drama. And it’s an umbrella term for the many different ways one can write what is called creative nonfiction. Memoir, for example, personal essay, biography, narrative history, and long-form narrative reportage may all fit under the creative nonfiction umbrella. Recently, as it has evolved, there have been offshoots to the genre such as speculative nonfiction, auto(biographical) fiction, lyric essay, and the visual essay, to name only a few.

Writers who write creative nonfiction are very different in voice, orientation, and purpose. But what they have in common is that they are, in one way or another, writing true stories that provide information about a variety of subjects, enriched by relevant thoughtful ideas, personal insight, and intimacies about life and the world we live in. And this scope and variety are exactly what make creative nonfiction significant and, these days, so incredibly popular.

“Freedom” and “flexibility” are words I like to use when defining creative nonfiction, for the genre invites writers to push boundaries and open doors, offering them the opportunity to use all of the techniques of the fiction writer (or the poet)—dialogue, setting, description, inner point of view (seeing the world through the eyes of the person they are writing about)—in order to capture a reader’s attention and enlighten and intrigue them through nonfiction.

There are very few rules for writers of creative nonfiction. You can predict the future, speculate about the past, or imagine what could have happened or what someone might have been thinking, as long as you don’t violate the reader’s trust, and in the process your own credibility. There are, however, limits to the freedom and flexibility that make creative nonfiction so attractive and compelling—legal, ethical, and moral issues that are challenging and, in many ways, impossible to clearly define. Freedom and flexibility and daring—are governed by responsibility, not just to the people we write about, but to those who read and publish our work.

Nonfiction itself has had a bad rap in the literary world. For a long time, it was commonly believed that writing nonfiction was generally inferior to the writing of poetry and fiction. “Nonfiction is a pleasant way to walk,” Larry McMurtry once wrote, “but the novel puts one on horseback, and what cowboy, symbolic or real, would walk when he could ride?”1

I remember reading this from McMurtry, who had written a great deal of nonfiction, in addition to his many novels and stories, and feeling more than a little annoyed and, at the same time, amused. He had to be joking, I thought. Or maybe he had just fallen off his horse. I pictured the comedian Rodney Dangerfield, who became rich and famous for the line “I get no respect,” which in many ways has been the story of creative nonfiction in a nutshell.

The addition of the word “creative” to nonfiction was at first controversial, but it gradually reversed the belief that nonfiction was somehow second class, a cut below poetry and fiction. It liberated all writers, journalists especially, releasing them from longstanding rules and boundaries that had been so restrictive and inhibiting. For novelists, poets, and essayists, “creative” encouraged experimentation and offered new avenues of expression. Scientists, physicians, attorneys, were intrigued by the notion of being creative and began to write true stories that humanized their professions. The interest in true stories motivated and opened doors for others who were not writers by trade to share their life experiences, finding

meaning in the process and fulfillment in the connections they forged with readers.

This transition—an awakening to the potential and power of nonfiction that allowed and encouraged creativity—did not happen overnight and was not without resistance and often bitter infighting. Change was difficult for the literary, journalistic, and academic communities, steeped in tradition and long resistant to new ideas, to accommodate. Indeed, the resistance in some corners far exceeded the scale of the change itself. As I point out in this book, the change was hardly drastic and was not really, when one looks back over the history of nonfiction, much of a change at all. Writers, including familiar and famous names you will recognize, such as Daniel Defoe, Charles Dickens, George Orwell, and many others, had been writing nonfiction that was creative and imaginative for centuries. The change, the adjustment that it precipitated, had much more to do with the approach or attitude toward nonfiction rather than its content and, of course, the idea that creative and nonfiction were not mutually exclusive. That change in approach and attitude is ongoing. The scope of nonfiction today, if it can still be called nonfiction, continues to evolve.

This book documents the evolution of the genre from its controversial beginnings to the respect and legitimacy it has achieved today. It highlights some of the history of the genre—the authors and events that most inspired and affected me and other writers of the genre at the time, including the impact of the new journalism, the reemergence of the essay, the surge of memoir. This book will be eye-opening to students and beginning writers. It will open doors and opportunities for more experienced writers who want to push the limits of their work and ideas and reach new readers.

Perhaps more important, this book is about the meaning of the genre, the revolution it initiated and the incredible impact over the years that it generated not just in literature or journalism, but to the changing culture and values worldwide. It’s about how women (and minorities), long ostracized by a white male good old boys’ network,

so much that they were sometimes not even permitted to write in their own names, in time became the dominant voices of the genre. And so very relevant today, it is about the ethics and morality that challenge writers, the behind-the-scenes revelations of how and why writers manipulate their material or, in some cases, make stuff up. This book will be of interest to all writers and to unknowing readers who may be surprised to learn that the true stories they have read and admired may not be as true as they believed. Readers will learn about the tricks of the true-story trade, like the compositing of characters, the compression of time and place, and the phrases writers often employ, like “larger reality,” “the untrue truth,” and “the poetic truth,” to justify those embellishments. Finally, the book will tell you how and why creative nonfiction became the people’s genre, how anyone with a story to tell, no matter how personal and intimate, no matter their background or education, was provided a forum and a vehicle to express themselves and justify and share their lives, their work, and their beliefs.

This book is not, however, meant to be a thorough and comprehensive examination of the history of the genre, which goes back hundreds of years and would probably require volumes; and if it were, I would not be the one to write it.

I am not, have never been, a scholar, by any means. In fact, unlike many of the students I teach or the writers I edit, I do not have a Ph.D. or MFA or any advanced degree. I was never a cardcarrying journalist or a failed novelist. I was just, at the time, the middle 1960s when I started out, a hippie motorcyclist with shoulder-length hair and unruly sideburns and all of the turquoise accoutrements of the era—who was also a wannabe nonfiction writer, trying to figure out what the writing life was all about and somehow become a part of it.

Until, eventually, I stumbled into the academy, or, as many of my colleagues in the English department at the University of Pittsburgh might have then said, “barged” my way in—long before creative nonfiction became creative nonfiction. As it turned out, I was in the right place at the right time, and it is fair to say that I was

somewhat of an opportunist. I realized in the early 1970s that some sort of literary transition in nonfiction and journalism was occurring, a transition that many writers, critics, and scholars, in and out of the academy, vigorously resisted. This conflict excited and invigorated me, and I instinctively, and perhaps naively and sometimes provocatively, defended it and simultaneously pushed it forward. To go back to McMurtry, I climbed on the creative nonfiction horse and rode it like hell.

Over time, mostly because of the ongoing resistance with which I was confronted, I became more than a little obsessed. In my own mind, the acceptance of creative nonfiction and the acceptance of an outsider-motorcyclist-interloper in the academy were one and the same thing. I went after that acceptance with a freewheeling or, some have said, “crazed” resolve.

In addition to starting CreativeNonfiction,the first literary journal to publish creative nonfiction exclusively, the publication that would become the flagship of the genre, I helped establish, despite ongoing and sometimes petty resistance from my colleagues, the first MFA program in creative nonfiction at the University of Pittsburgh, and, later, the first low-residency MFA program, at Goucher College. I started a creative nonfiction book series that led to a full-fledged book imprint. I initiated the first all-creativenonfiction writers’ conference, which brought together for the first time the most prominent voices of the genre—Susan Orlean, John McPhee, Gay Talese, Mary Karr, Joyce Carol Oates, Tobias Wolff, and George Plimpton, to name just a few—to interact with student participants who came from throughout the world to learn about creative nonfiction. These and many others, like Norman Mailer, Lillian Ross, Truman Capote, Joan Didion, brought respectability to the genre and opened doors for the generations of writers they inspired.

Over the years, with every opportunity, I have taken my creative nonfiction message on the road, across the United States and into Australia, China, Egypt, New Zealand, Ireland, England, Israel, beating the creative nonfiction drum. Later I introduced creative

nonfiction into a science policy think tank. James Wolcott, in a scathing article that ridiculed the genre in VanityFairin 1997, in which he dubbed me “the godfather behind creative nonfiction,” compared me, in reference to all of my drum-beating activities, to a “human octopus.”2

My version of the evolution of the genre is rooted in the changes occurring in journalism in the 1960s and 1970s, but there are, for sure, many other ways to tell the creative nonfiction story. There are those who would begin in the sixteenth century, with Michel de Montaigne, who coined the term “essay” and is often referred to as the father of the essay.

It is certainly true that essays have always contained many elements of what came to be known as creative nonfiction, and maybe it would even be all right to say, in retrospect, that Montaigne was the first creative nonfiction writer. But the emergence of creative nonfiction, as the genre—the umbrella—is known and accepted today, did not take place until hundreds of years after Montaigne. Essayists, however, eventually joined and invigorated the creative nonfiction movement and turned it into the rich, diverse, and legitimate genre it is today. There are probably more essayists writing creative nonfiction today than there are journalists. Even journalists these days tend to refer to their long-form work as essays. The word “article” has become somewhat of an anachronism.

A major part of the story I am telling in this book is how creative nonfiction came to be accepted in the academy—an unlikely wellspring for what started as such an unscholarly invasion of an established, conservative, and seemingly impenetrable bastion. And how over a period of years, writers in the academy, in creative writing programs, began developing a creative nonfiction pedagogy and a community for their students, and how those students and their students after that transformed a bare blip in the literary landscape into a legitimate and flourishing genre that would soon equal or outpace poetry and fiction. And how the writers in the academy brought together what were then two factions—journalists

and literary writers—and how this union helped change the course, the flavor, and the direction of the growth of literary art, not just in the United States but from a global, all-encompassing perspective. And not just into the humanities, but into many other academic disciplines.

But getting to where we are today—to the ascendancy of creative nonfiction as the fourth and most active and visible genre—was a real battle, an often disagreeable and circular series of debates over long-held and outmoded ideas, over class and prejudice, over literary and journalistic turf, and, not surprisingly when writers are involved, over insecurity and self-identity and, most of all, over words. These debates went on for many years, until gradually and sometimes painfully, nonfiction that was creative was recognized as an art form equal to poetry and fiction.

More than any other factor over the past fifty years, it was what I like to call, with more than a hint of embellishment, the “literary fistfighting” of these debates, between those who held the line and resisted change and those who defied and challenged them, that triggered an evolution of literary art, expanding its scope in ways that might have never been predicted or imagined. This is the story of how that all came about, told from the perspective of an outsider who inadvertently and reluctantly became an insider.

PART 1