Natural General Intelligence

How understanding the brain can help us build AI

Christopher Summerfield

Department of Experimental Psychology, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP, United Kingdom

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries

© Oxford University Press 2023

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

First Edition published in 2023

Impression: 1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Data available

Library of Congress Control Number: 2022946634

ISBN 978–0–19–284388–3

eISBN 978–0–19–265766–4

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780192843883.001.0001

Oxford University Press makes no representation, express or implied, that the drug dosages in this book are correct. Readers must therefore always check the product information and clinical procedures with the most up-to-date published product information and data sheets provided by the manufacturers and the most recent codes of conduct and safety regulations. The authors and the publishers do not accept responsibility or legal liability for any errors in the text or for the misuse or misapplication of material in this work. Except where otherwise stated, drug dosages and recommendations are for the non-pregnant adult who is not breast-feeding

Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. Oxford disclaims any responsibility for the materials contained in any third party website referenced in this work.

Preface

Artificial intelligence (AI) research is progressing at blistering pace. Over the past 10 years, many significant milestones have been reached. AI systems have been able to surpass human expertise in playing strategic games, to produce quite plausible natural language, and even to assist in making groundbreaking scientific discoveries. These advances have become possible through dramatic gains in the availability of powerful computation. However, they have also been driven by innovation in the algorithms and architectures from which AI systems are built.

Over the same period, cognitive scientists and neuroscientists have been busy developing new tools and theories for understanding the brain and behaviour in humans and other animals. Their ultimate goal is to understand the principles that make natural intelligence possible, by describing computational mechanisms, defining cognitive systems, and examining their neural implementation.

These two tribes of researchers—those concerned with building and understanding brains—have long regarded each other with mutual curiosity. Cognitive scientists and neuroscientists are excited by the opportunities opened up by progress in AI research. What are the algorithms and architectures driving progress in AI? How do they resemble, or differ from, those in biological brains? At the same time, many computer scientists are fascinated by natural intelligence—how the brain works in humans and other animal species. What is there to learn from nature’s solution for generally intelligent agents? Should we adopt the principles of natural intelligence for building AI? Now, more than ever, there is an opportunity for the exchange of ideas between those who study brains and those attempting to build them. Unfortunately, however, this endeavour can be held back because terminology, concepts, and theories used in one discipline are often opaque to researchers in the other, their goals and approach are different, and researchers in the two domains have limited opportunities to interact and share ideas.

The purpose of this book is to try to bridge this divide. Its focus is on the points of connection between the fields of cognitive science, neuroscience, machine learning, and AI research. Its goal is to describe advances in AI research in the language of psychology and biology, and to map theories of the brain and cognition onto algorithmic and architectural innovation in computer science. Along the way, the book tackles long-standing questions about intelligent systems that are relevant to neuroscientists and AI researchers alike. What does it mean for an agent to be intelligent, and what are the cognitive and computational ingredients of intelligence? Should we study the human mind to build artificial brains? Why is it that AI systems are often good at what appear to be hard tasks, but flounder when asked to do simple things? What is it that makes the human mind so versatile—but also so prone to error? What is the outlook for the future—are generally intelligent artificial agents around the corner, or are we still light years away?

Many of these issues have become controversial. In particular, the question of whether natural intelligence is a viable pathway to building AI has become a focus of debate. At times, it feels like a minor culture war is welling up in the field, with some researchers stridently arguing that the study of natural intelligence has always been a distraction for AI, and others claiming that the limitations of current systems could be overcome if only we looked to biology for computational solutions. In tackling these questions, I hope to give both sides of the argument the deep consideration they deserve.

I felt qualified to write this book because despite having trained as a psychologist and cognitive neuroscientist, I have been involved for more than 10 years with the AI research company DeepMind. As part of my role there, I have had the privilege of following developments in AI research alongside some of the world’s foremost practitioners. Readers with expertise in machine learning may find the coverage of current work in AI research somewhat partial and incomplete. One manifestation of this is a bias to describe work conducted at DeepMind. This is not because of a wish to promote or aggrandize any institution with which I have a personal connection. It is simply a reflection of my greater familiarity with work being conducted there.1 Neuroscientists may notice that there are several topics that I overlook. They might reasonably complain that my portrait of natural general intelligence described here grossly privileges vision over the

other senses, lacks any coherent account of affective processing (emotion), gives short shrift to the psychological study of language, and—sticking to a long and venerable tradition in cognitive neuroscience—never once mentions the cerebellum. For these omissions, I apologize.

I began to write in spring of 2021 and finished some 10 months later. However, AI research is moving at speed. For example, when I first put pen to paper, it was less than a year since the seminal paper from OpenAI described the large language model called Generative Pretrained Transformer 3 (GPT-3), and the field was still reeling from the discovery that natural language processing (NLP) might finally be coming of age. Today, there is a whole branch of AI research devoted to large-scale ‘Foundation’ Models, including striking several multimodal (text-to-image) models, whose performance is similarly remarkable. There is even one system that will evaluate the moral status of activities described in natural language,2 which is undoubtedly the first NLP system that is genuinely entertaining to use.

Delphi speculates:

‘writing a long and boring book about natural general intelligence’ it’s okay

Given the pace of progress, I am sure that by the time this book is published, many of the claims and ideas will already be out of date. However, the foundational questions which the book tackles (Should we look to natural intelligence to build AI? What are the basic ingredients of intelligence for either humans or AI systems?) have been debated for more than half a century and are unlikely to be resolved any time soon.

I was only able to write this book because of the patience and forbearance of both colleagues and family. To my research groups in Oxford and London: I am sorry for all those times I made myself unavailable in order to focus on writing. To my family: I am sorry for spending many weekends in front of the computer. I am particularly grateful to those people who read the drafts and helped shape my writing. These include: Tim Behrens, Sophie Bridgers, Zoe Cremer, Mira Dumbalska, Sam Gershman, Keno Juechems, Andrew Saxe, Hannah Sheahan, MH Tessler, and Jess Thompson. My greatest thanks go to my wife Catalina Renjifo who listened to me read the whole thing aloud, with plausible enthusiasm, and made so many excellent suggestions.

Mark Twain famously said that:

There is no such thing as a new idea. It is impossible. We simply take a lot of old ideas and put them into a sort of mental kaleidoscope. We give them a turn and they make new and curious combinations.

This book is a bit of a mental kaleidoscope. The ideas that it contains all came from conversations I have had about the nature of intelligence, and how the brain works, with mentors, colleagues, and friends over the past 20 or so years. I am grateful to you all.

Oxford 2 March 2022

1 And, at least in part, because DeepMind was founded around the idea that understanding natural intelligence is one promising pathway to building AI.

2 See https://delphi.allenai.org/.

Contents

Abbreviations

1. Turing’s question

The ghost in the machine

AI as neural theory

Mercurial optimism

Deep everything

Shaking your foundations

Gaming the system

2. The nature of intelligence

The polymathic principle

Lab smarts and street smarts

The Swiss cheese critique

Look, no hands!

3. The language of thought

Thinking and knowing

Intelligences A and B

The units of thought

The symbolic mind

Mental models

Reaching the banana

Your brain as statistician

Playing Lego with concepts

4. The structure of knowledge

Total recall

Perceptrons in space

Maps in the mind

Deep dreams

When there is no there, there

5. The problem of abstraction

Molecular metaphors

Playing Twenty Questions with space

Abstractions as affordances

Luke Skywalker neurons

6. The value of action

Climb every mountain

The atoms of memory

The basements of the brain

The key to exploration Is reward enough?

7. The control of memory

The eligibility of experience

The butcher on the bus

The problem of a changing world

Finding structure in time

Mental gymnastics

Banishing the homunculus

Learning simple programs

8. A picture of the mind

5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 7.7 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 8.6

Where is my mind?

Inductive biases

The best of all possible brains? Is the mind flat?

Concepts and programs

Artificial intelligibility

References

Index

Abbreviations

2D two-dimensional

3D three-dimensional

AGI artificial general intelligence

AI artificial intelligence

ALE Arcade Learning Environment

APA American Psychological Association

API application programming interface

ATL anterior temporal lobe

BPL Bayesian program learning

CLIP contrastive language–image pre-training

CLS complementary learning systems

CNN convolutional neural network

Covid-19 coronavirus disease 2019

CPC contrastive predictive coding

CPU central processing unit

dACC dorsal anterior cingulate cortex

DG dentate gyrus

DLPFC dorsolateral prefrontal cortex

DNC differentiable neural computer

DND differentiable neural dictionary

DQN Deep Q Network

EEG electroencephalographic

ERC entorhinal cortex

FEP free energy principle

fMRI functional magnetic resonance imaging

GAN generative adversarial network

GPS General Problem Solver

GPT-3 Generative Pretrained Transformer 3

GPU graphical processing unit

HLMI high-level machine intelligence

ICA independent component analysis

IID independent and identically distributed

IQ intelligence quotient

LIP lateral intraparietal

LSTM long short-term memory

LTP long-term potentiation

MCTS Monte Carlo tree search

MDP Markov decision process

MEG magnetoencephalography

MIT Massachusetts Institute of Technology

MNIST Modified National Institute of Standards and Technology database

MRI magnetic resonance imaging

mRNA messenger ribonucleic acid

MTL medial temporal lobe

NART National Adult Reading Test

NeurIPS Neural Information Processing Systems

NGI natural general intelligence

NLP natural language processing

NMDA N-methyl-D aspartate

NPI neural program induction

PBWM Prefrontal Basal Ganglia Working Memory

PCA principal component analysis

PDP parallel distributed processing

PFC prefrontal cortex

pfs/days petaflop/s-days

PMG Pribam, Miller, and Galanter

PPC posterior parietal cortex

PRC perirhinal cortex

PSSH physical symbol system hypothesis

QA question answering

RDM representational dissimilarity matrix

RL reinforcement learning

RND random network distillation

RNN recurrent neural network

RPM Raven’s Progressive Matrices

seq2seq sequence-to-sequence

SNARC Stochastic Neural Analog Reinforcement Calculator

SNARC spatial–numerical association of response codes

TD temporal difference

TE anterior parts of the temporal lobe

TOTE ‘test, operate, test, exit’

TPU tensor processing unit

UCB upper confidence bound

VAE variational autoencoder

VTA ventral tegmental area

WEIRD Western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic

WReN wild relation network

Turing’s question

I propose to consider the question, ‘Can machines think?’ This should begin with definitions of the meaning of the terms ‘machine’ and ‘think’.

Turing 1950

1.1 The ghost in the machine

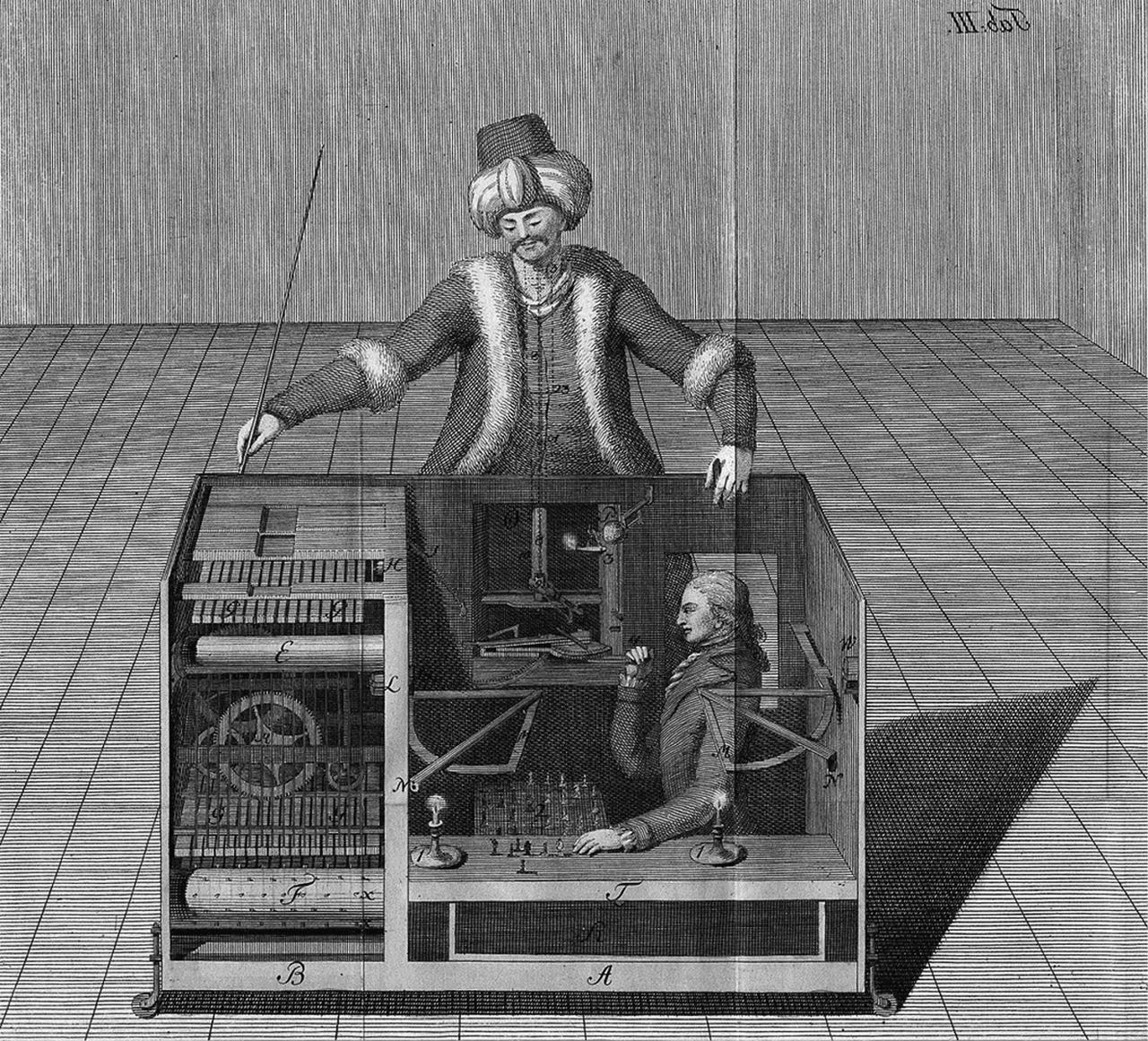

One day in 1809, Napoleon Bonaparte—Emperor of France and one of the greatest military commanders in history—lost a game of chess. According to eyewitness accounts, he was not best pleased. Tipping over his king, he swept the chess pieces stormily to the floor and marched out of the room in Schönbrunn Palace, Vienna, where the contest was being held. Despite his undoubted prowess on the battlefield, Bonaparte was actually a rather mediocre chess player. But his frustration was perhaps understandable. It was the third game in a row he had lost—and his opponent was not even human.1

Bonaparte had just been trounced by the Mechanical Turk—a chessplaying automaton that toured Europe in the late eighteenth and nineteenth century, chalking up victories against nobility, statesmen, and assorted chessophiles. The Turk prompted wild speculation among Europe’s intelligentsia as to how a machine could possibly have mastered the game of chess. On a later visit to North America, it was witnessed by the writer Edgar Allan Poe, who claimed that:2

Perhaps no exhibition of the kind has ever elicited so general attention as the Chess-Player [ … ] We find every where men of mechanical genius, of great general acuteness, and discriminative understanding, who make no scruple in pronouncing the Automaton a pure machine.

However, the Turk was not a pure machine. Only humans played truly expert chess until the 1990s, when computers approached and then surpassed

grandmaster level—culminating in IBM’s Deep Blue famously winning against the reigning world champion Gary Kasparov in 1997 (Kasparov, like Bonaparte, was unhappy—and promptly accused IBM of cheating). IBM was not cheating, but the Turk was—a human chess expert was crammed uncomfortably into an interior compartment, monitoring the board position upside down with an ingenious magnetic device (Figure 1.1). It was the power of the human mind, and not an early spark of mechanical intelligence, that allowed the Turk to humble opponents and bamboozle onlookers.

Fig. 1.1 The Mechanical Turk. Drawing by Joseph Racknitz. Humboldt University Library (source: Wikipedia).

Although the Mechanical Turk was a hoax, its story exposes our deep fascination with thinking machines. It is an allure that stretches back deep into cultural prehistory: from statues animated with the breath of their inventors, and monsters stitched together in makeshift laboratories, to the first stirrings of rebellion among a robot underclass.3 In his remarkable 1909 novella The Machine Stops, E. M. Forster envisages a machine that takes the form of a vast, sentient communications network and has enslaved the humans that built it—confining them to a solitary, subterranean existence. By the mid-twentieth century, however, these dreams of mechanical slaves and android overlords had begun to give way to the serious prospect of constructing intelligent machines using the formal languages of logic and mathematics.

The publication of Alan Turing’s seminal paper Computing Machinery and Intelligence in 1950 is often said to mark this turning point. In the paper, Turing asks: could a digital machine think? In posing this question, Turing is not inviting us to an exercise in philosophy of mind. He is not asking whether a machine can think in principle. 4 Rather, he is asking a practical question: does digital computation permit us to build a machine that can think in ways indistinguishable from a human? If so, how would this be possible? Some 70 years later, artificial intelligence (AI) research is advancing at a dizzying pace. However, Turing’s question remains unanswered and has never seemed more urgent.

This book is written at a time of both great excitement and considerable uncertainty about progress in AI research. There is no doubt that deployment of new AI technologies is already dramatically reshaping society around us. This most immediate impact is that simple, but powerful, machine learning systems are relentlessly insinuating themselves into every aspect of our daily lives. An ever-greater fraction of the information we consume, and the decisions we make, occur through a digital interface, such as a phone, tablet, or computer. Algorithms embedded in websites and applications recommend consumer products and new social contacts, curate news and other online content for us, and increasingly govern our interactions with the wider society, including institutions providing education, health, or justice. Commentators have noted that Forster’s vision of The Machine seems weirdly prescient of our AI-mediated online existence.5 Meanwhile, behind the scenes, tools from machine learning are accelerating innovation in science and technology. For example, in late 2020, a deep neural network

was used to solve one of the most significant problems in structural biology —how to predict how a protein will fold from its amino acid sequence— with potentially far-reaching implications for drug discovery and environmental sustainability.6 Collectively, these advances in AI have profound implications for how we live our lives, both as individuals and as a society. However, they are not the focus of this book.

Instead, I will start by examining the other, more ambitious goal of AI research today: to build what is often called artificial general intelligence (or AGI). As we shall discuss, the field currently lacks a crisp definition of what building AGI might entail. However, the goal is roughly to build an artificial system that behaves with the same or greater intelligence than a healthy, educated adult human, and can thus be deployed to automate complex tasks and to solve currently intractable problems. This sort of general intelligence is, of course, exactly what Turing had in mind when he talked of a ‘thinking machine’.7 But over the decades since his 1950 paper, the prospect of a general AI has gone from respectability to ill-repute and back again. Just a decade ago, discussions of general intelligence—and the coming ‘Singularity’, when machines rise up and act like humans—were largely taboo among AI researchers, being associated instead with the wilder imaginings of eccentrics with parallel interests in transhumanism and intergalactic colonization. Today, however, AGI research has entered the academic mainstream. Over the past few years, a small army of research companies have been founded with the express intent of building general AI. Prominent among them are DeepMind in London and OpenAI in San Francisco, which collectively have contributed many of the more jawdropping leaps in recent AI progress, and whose research we shall consider in some detail below.8 As often envisaged—that is, as a general system capable of solving complex, currently elusive problems—an AGI would be the most significant and valuable technology that humanity has ever built. It is barely surprising, thus, that advancing progress in AI has attracted exuberant interest from investors, journalists, and politicians. However, there is also a great deal of uncertainty. Much of this comes from within the AI research community itself, where there is significant disagreement about what, about how, about when, and about why. AI researchers disagree about what they are building—should an AI be physically embodied, negotiating the real world, or instantiated as a computer program that dispenses wisdom from the relatively safer confines

of the internet? They disagree about how AI should be built—should designers draw upon our human knowledge of the world and raise their agent to imitate human-like behaviours—or should they build AI from a clean slate, with statistical principles alone as their guide? Researchers— including philosophers and associated futurists—disagree about when we can expect the first glimmerings of general intelligence in our artificial systems—with optimists forecasting the Singularity within decades or less, and pessimists dismissing AGI altogether as a quixotic fantasy.9 And finally, and most significantly, there is insufficient discussion of why general AI should be built. What is AI for, and what will it do? Companies such as DeepMind and OpenAI promise to build AI for global human benefit—a well-intentioned, if somewhat vague, commitment—but whether this is possible remains to be seen. As with every powerful new technology, there is ample scope for AI to be catastrophically misused.

1.2 AI as neural theory

Naively posed, Turing’s question has a trivial answer. Machines that can think already exist. They are called brains and there are many trillions of them on this planet. You have one yourself, hewn by the deep time of evolution and fine-tuned by long years in the school of life. Whilst AGI remains a dream, NGI—natural general intelligence—is an ever-present reality. The thesis of this book is that in the attempt to build AI, we should pay attention to how evolution has solved natural intelligence. Biology provides us with a reassuring existence proof for thinking machines. But, I will argue, it does more than that. It gives us a sense of the set of problems that intelligent systems evolved to solve, and a rough guide to the solution concepts that nature has devised. I will argue that we can think of natural intelligence as a blueprint for AI.10

Understanding natural intelligence is the province of researchers in the cognitive and neural sciences. This group includes those called computational and systems neuroscientists, who conduct research by manipulating and recording from neural circuits, and modelling brain activity, as well as both psychologists and cognitive scientists, who try to reverse infer how brains work by examining the structure of behaviour, from both a normative standpoint (how should people behave?) and a descriptive standpoint (how do people tend to behave in practice?). Whilst the question

of whether evolution’s recipe for intelligence will prove a fruitful inspiration for AI research is a question of enduring debate, the converse is less controversial. Psychology and neuroscience have already been powerfully shaped by advances in machine learning and AI research, and there is much more yet to learn.

This symbiosis between neuroscience, cognitive science, and AI research began many decades ago. Important examples include neuroscientists’ excitement with reinforcement learning (RL) architectures as theories of motivated choice, or more recently with deep neural networks as theories of perception and memory.11 But AI has a great deal more to offer the sciences of the brain and mind. This is because AI researchers now routinely tackle a problem that most neuroscientists consider too ambitious to contemplate: modelling the behaviour of large-scale, integrated agent architectures in dynamic, naturalistic environments. AI researchers model complex behaviour holistically, rather than dissecting it with the scalpel of experimental control. This opens the door to new ways of thinking about intelligent behaviour and its computational underpinnings in biology, and offers opportunities for new synergies among researchers wishing to build and understand brains.

Neuroscientists have discovered a great deal about brain function over the last century, but for the most part, this knowledge remains fragmentary. It is modish to lament how little we actually understand about how the mind works. Indeed, brains are formidably complex, and so the field has adopted a divide-and-conquer approach—individual research groups focus relatively narrowly on a specific aspect of brain function, using a limited set of methods, often in a single species. For example, a typical lab in systems neuroscience might focus on understanding how olfaction works in flies, how rodents navigate, or how humans make prosocial choices. We have learnt a great deal from focal research programmes such as these, but it is notable that the field has not yet been successful in identifying plausible, large-scale principles for intelligent behaviour.

Behaviour is often easier to study than brain activity. Measurements are simpler to carry out, analyse, and interpret. In neuroscience’s sister discipline of psychology, thus, many experiments involve measuring button presses and reaction times,12 rather than charting the activity of hundreds of neurons with millisecond precision. The lower complexity of the recorded signals allows research to progress at pace, making it easier to build

thematically diverse research programmes. It is thus perhaps unsurprising that psychologists have been more prone to formulate theories with broad explanatory reach. The history of experimental psychology is punctuated by the rise and fall of large-scale frameworks, such as those that rely on rewardbased trial-and-error learning (behaviourism), learning in neural networks (connectionism), or decisions made by probabilistic inference (Bayesianism), as well as by theories that emphasize more structured forms of information processing (cognitivism).

However, each of these frameworks suffers from important limitations.13 Behaviourism struggles to explain forms of learning that rely on imitation or instruction and cannot account for the complex structure of language or memory systems. Bayesianism places poor constraints on representation learning and suffers from issues of computational tractability and falsifiability. Connectionism fails to explain how old knowledge and new knowledge are combined, and overlooks the native structure given to the mind at birth. Cognitivism is more like a jumbled set of constraints on information processing than a coherent computational framework, and thus tends to bound behavioural predictions only loosely. Each of these approaches has thus ultimately fallen short. Today, there is no single prevailing theory of how behaviour is structured, and no overarching account of the computational origins of intelligence.

Thus, neither psychology nor neuroscience has provided us with something resembling a standard model.14 In this sense, they differ from adjacent disciplines, such as physics or evolutionary biology, where research is scaffolded around strong, unified theoretical frameworks that propose fundamental forces or principles for natural selection. The science of brain function lacks general theories. We might say that is nomothetically impoverished.

Remarkably, however, general theories of brain function are starting to emerge in computer science departments and AI research institutes. This is because the brain modelling challenge for AI researchers is fundamentally different in nature and scope from that tackled in neuroscience. Notably, it does not afford the soft option of dividing and conquering, because the whole agent will fail if any of its component functions (e.g. perception, memory, or decision-making) is not up to scratch. Moreover, there are at least three challenges for modelling intelligence that AI researchers routinely tackle, but neuroscientists have mostly ignored thus far. To describe these

challenges, I use the terms end-to-end learning, scale, and untethering. By addressing these challenges, neuroscientists might begin to open the door to broader theories of intelligent brain function.

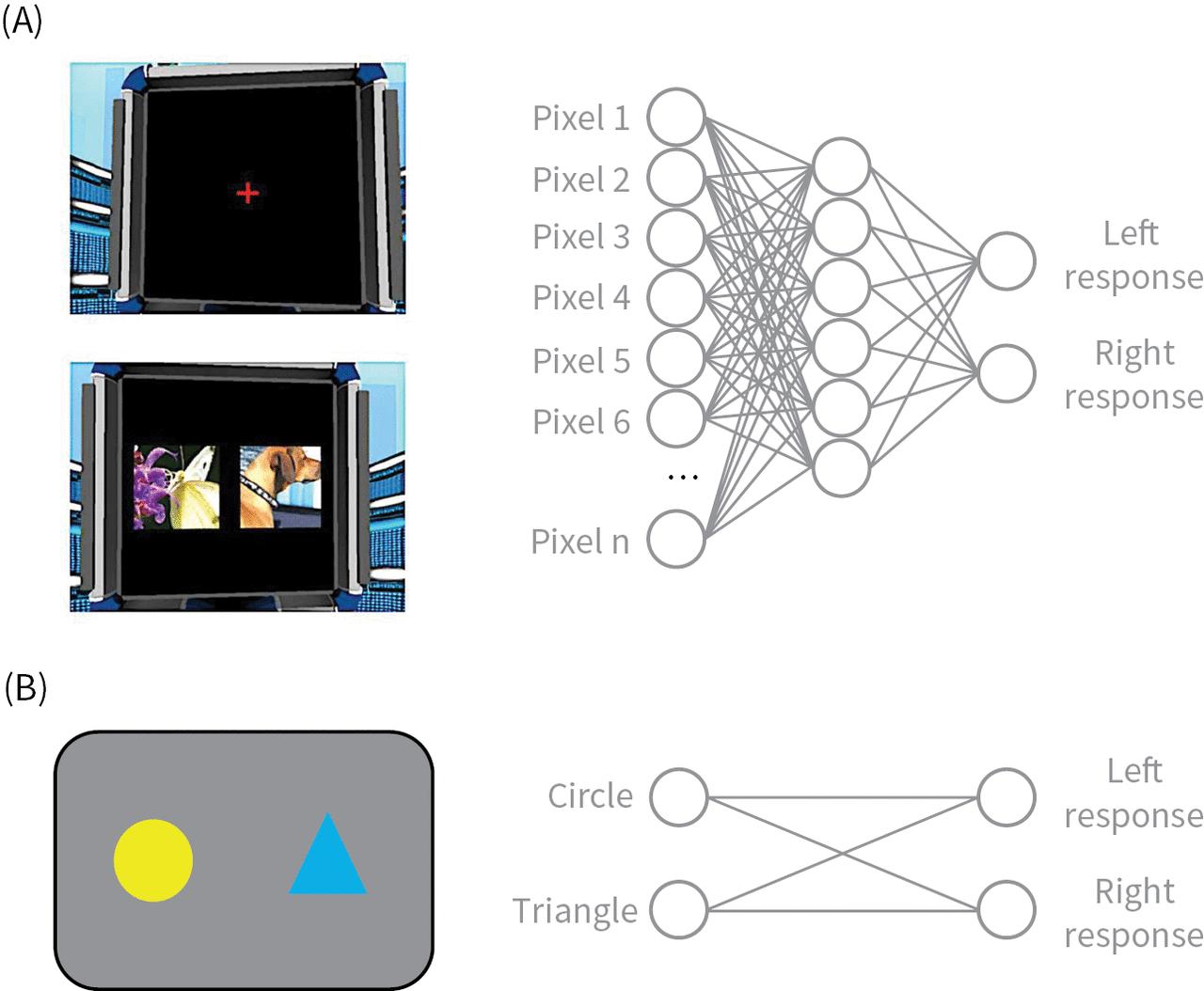

Fig. 1.2 Illustration of end-to-end learning. (A) Images seen by a deep neural network trained to perform a bandit task from image pixels. The network is trained end-to-end, from pixels to response. (B) Illustration of a typical bandit task from a neuroscience experiment. The input space is handcrafted by the researcher.

Image in (A) is reprinted from Wang et al. (2018).

End-to-end learning means that an agent acquires the building blocks of intelligence by experience, with minimal researcher intervention (Figure 1.2). In the era of modern AI research, powered by deep networks, end-toend learning has become the norm. This contrasts with standard practice in cognitive science, where the relevant input states, and the computations enacted upon them, tend to be hand-designed by the researcher. For example,

in one popular paradigm that we shall encounter in Chapter 6, known as a bandit task, participants choose repeatedly between virtual slot machines (or bandits) that pay out money with unknown probability. Neuroscientists like to think of this as a simulacrum of the challenge faced by an animal foraging for reward in an uncertain environment. A common assumption is that participants learn and decide by representing a latent estimate of the value of each action in each state (‘how good is the left response to the red stimulus?’). The researcher will thus initialize the space of possible states and actions in the agent’s brain by hand, allowing learning to proceed as value estimates of each state and action are updated according to a preferred learning rule.15

By contrast, an AI system, for example one that solves the task directly from the screen pixels, has to learn a set of internal representations that allows it to maximize reward from scratch. In other words, it has to learn that the slot machines are the things that matter in the first place. This means that AI researchers, rather than neuroscientists, have led the charge in trying to understand the principles of representation learning, that is how neural codes form as a function of experience—or specifically, as a function of its objective or cost function. Recently, neuroscientists have tried to catch up, often by copying the way that research is conducted in AI research. For example, it is now popular to use benchmark machine learning problems as tools for psychological experimentation, in an attempt to study how representations are formed in biology. This is a good start, but to make significant progress, we need learning paradigms that more closely resemble the problems that biological agents evolved to solve.

Secondly, the challenges that AI researchers set themselves are greater in scale. They come much closer to mirroring the mind-boggling complexity of the natural world. Neuroscience studies typically privilege experimental control over ecological validity, using home-grown, artificial stimuli and simple, stylized tasks, such as those that involve detecting whether a grating appears on the left or right of the screen.16 By contrast, AI researchers usually draw their stimuli from external sources—they label photos that have been uploaded to the internet, download Wikipedia for language modelling, or scrape millions of board games from online servers to train their agents. Neuroscientists mostly ignore the question of whether the findings they obtain in simple settings will scale up to more realistic environments. For example, a typical model of the bandit task referred to above might comprise

a handful of states and two or three free parameters, such as the learning rate or slope of the choice function. By contrast, even a simple neural network model will have hundreds of units (allowing an almost limitless number of possible states), and thousands of freely tunable synaptic weights (parameters). For AI researchers, questions of scalability are always central to the research programme. If your algorithm doesn’t scale, it’s probably not worth pursuing.

Finally, the agents built by AI researchers today actually have to behave. This is not usually the case for biological simulations, where models are instead optimized to match the recorded behaviour of humans or experimental animals as closely as possible. Psychological models are thus constantly re-tethered to empirical data by this fitting process.17 Turning again to our bandit task example, the model learns from the feedback (reward) given to observed choices, irrespective of which bandit it would itself have chosen. By contrast, in AI research, it is usually neither possible nor desirable to provide guardrails for agent behaviour using empirical data, and so agents are unrolled in the environment—they are left to their own devices, suffering the consequences or reaping the benefits of their own actions. This makes the challenge of modelling and understanding behaviour much harder.

These three challenges—end-to-end learning, scale, and untethering— highlight the divergent goals of the two fields. AI researchers typically seek to meet a performance goal, such as reaching state-of-the-art performance on a benchmark challenge, whereas neuroscientists are typically concerned with enhancing the goodness of fit of their model to human or animal data. But paradoxically, the pursuit of building agents that can learn for themselves in complex, naturalistic environments, without the constant guiding hand of the researcher, is leading to the beginnings of an integrated theory in AI research of the ingredients that are required for intelligence. These take the form of specifications for memory architectures, attentional constraints, perceptual priors, compression principles, and planning algorithms.

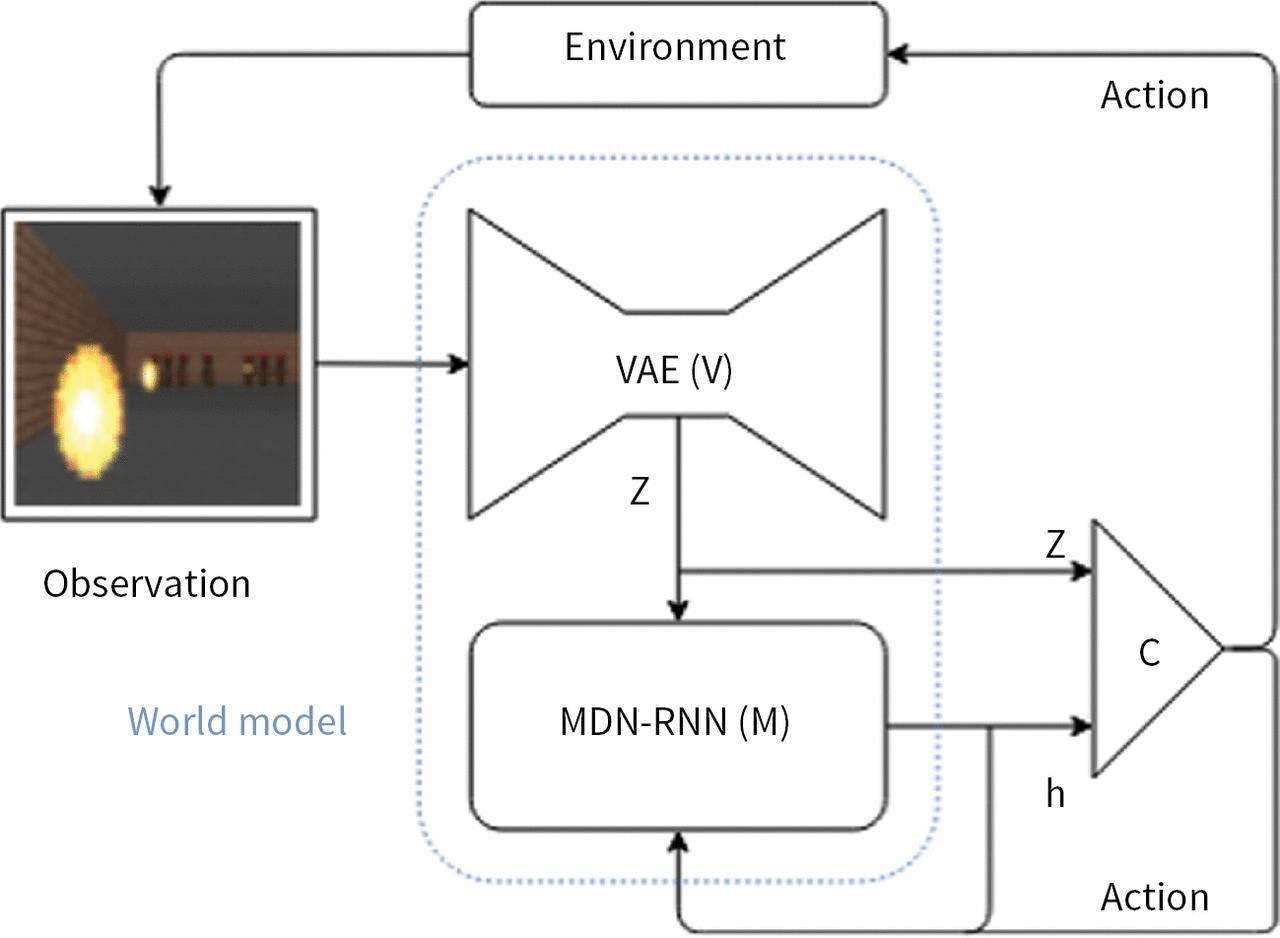

One example is a class of agent that benefits from a world model for perception and memory, as well as a separate module for control. For example, in one such agent, a self-supervised deep neural network learns to extract high-level features from quasi-naturalistic high-dimensional data such as a video, a recurrent neural network learns to predict the future in the latent space of abstract representations, and a controller learns a policy using

tools from RL. This type of architecture rises to the thorny challenge of fitting the components of a brain together into a single, integrated system for neural computation. Figure 1.3 shows the architecture of an example world model that trained to driving a racing car in a video game.18

Fig. 1.3 An example of a world model. The agent’s behaviour is governed by the interaction of modules for sensory processing (V), memory (M), and control (C). Image is from Ha and Schmidhuber (2018).

Throughout this book, we discuss tools and methods from AI research, and how they can inform neuroscience research. Conversely, we will consider the principles that allow biological agents to display intelligent behaviours, and how they might help us build AI. But first let’s return to survey the state of current AI research. We will begin with a historical perspective.