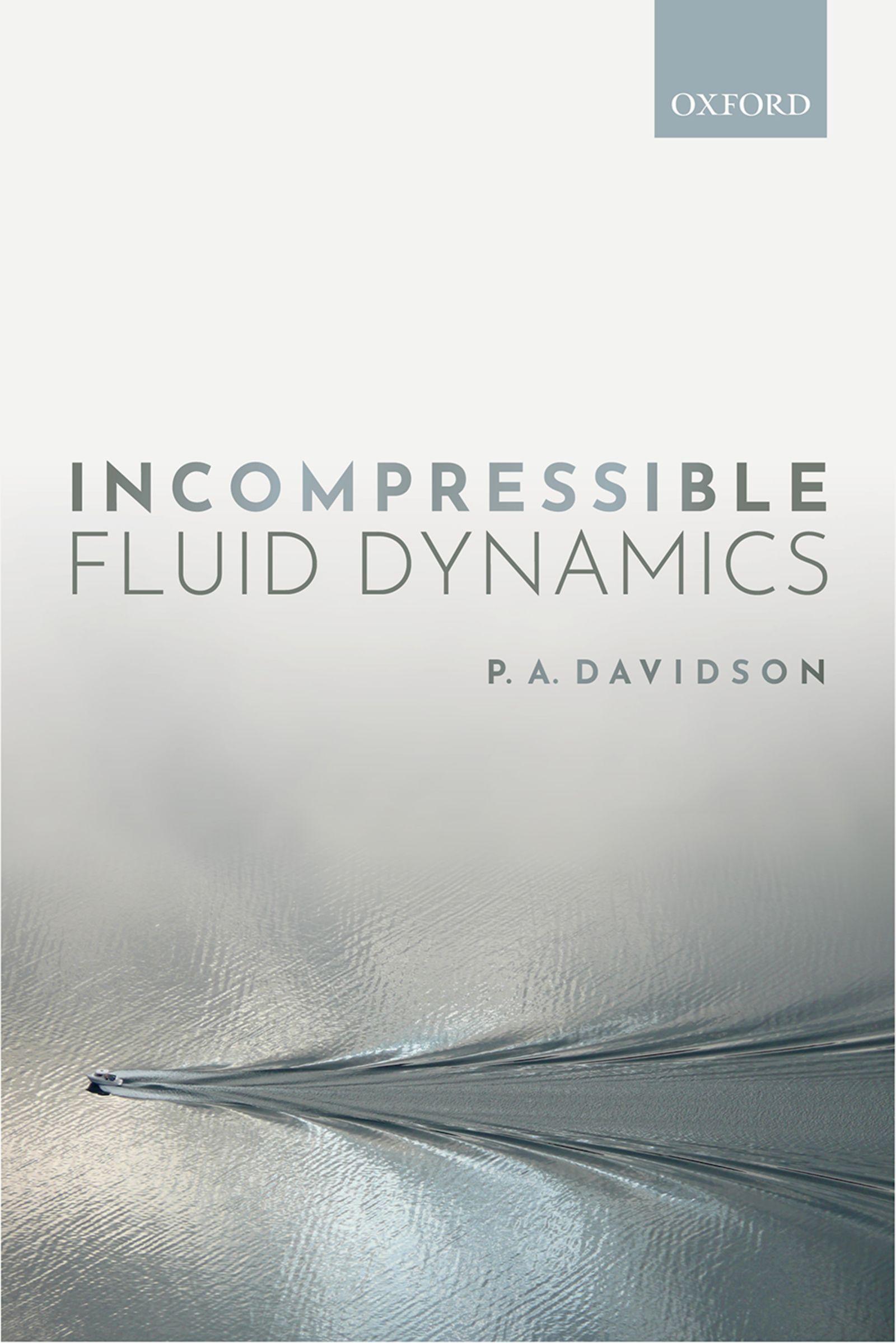

PREFACE

Thisisatextbookforadvancedundergraduateandpostgraduatestudentsofengineering, appliedmathematics,andphysics.Itisnotintendedtobeencyclopaedicincoverageandso difficultchoiceshadtobemaderegardscontent.Thetopicsaddressedhavebeenchosen largelyonthegroundsthattheyhelpestablishthebroadconceptualframeworkofthe subject,exposekeyphenomena,andplayanimportantroleinthemyriadofapplications thatexistinbothnatureandtechnology.Ofcourse,thechoiceofmaterialisultimatelya personalone,andsotheauthorseekstheindulgenceofthosereaderswhofindthattheir favouritetopicisgivenlessspacethantheywouldhaveliked.

Intheprefacetohis1946text MechanicsofDeformableBodies,ArnoldSommerfeld comments:

Ishallnotdetainmyselfwiththemathematicalfoundations,butproceedasrapidly aspossibletothephysicalproblemsthemselves.Myaimistogivethereaderavivid pictureofthevastandvariedmaterialthatcomeswithinthescopeoftheorywhena relativelyelevatedvantage-pointischosen.

Thisauthorfullyendorsesthesesentiments,andsophysicalinsighthasbeengiven priorityovermathematicaldetail,asseemsappropriateforasubjectasphysicallyrichas this.Forexample,whenitcomestotheclassicaltheoryofpotentialflow,itisprobablyless importantforastudenttomastertheintricaciesofsomefiendishlycunning19th-century potentialthantoappreciatethat,outsidethefieldofwaterwavesandafewchoiceproblems inaerodynamics,anirrotationalanalysiswill,mostofthetime,utterlyfailtocapturethe realflow.Itisalsoimportantforthestudenttounderstandthatthisfailureisnotmerelyan embarrassinginconvenience,butrathertellsussomethingquiteprofoundaboutthenature offluiddynamics.Inthisrespectitis,perhaps,appropriatetorecallRayleigh’swhimsical, buttelling,observation:

Thegeneralequationsof(inviscid)fluidmotionwerelaiddowninquiteearlydaysby EulerandLagrange…(but)someofthegeneralpropositionssoarrivedatwerefound tobeinflagrantcontradictionwithobservations,evenincaseswhereatfirstsightit wouldnotseemthatviscositywaslikelytobeimportant.Thusasolidbody,submerged toasufficientdepth,shouldexperiencenoresistancetoitsmotionthroughwater.On thisprinciplethescrewofasubmergedboatwouldbeuseless,but,ontheotherhand, itsserviceswouldnotbeneeded.(1914,ScientificpapersofLordRayleigh,p237)

WithRayleigh’swarninginmind,theviscousequationsofmotionandtheassociated conceptsofboundarylayersandturbulenceareintroducedpriortopotentialflowtheory anditsapplicationsinaerodynamicsandsurfacewaves.Inthisway,itishopedthatthe

studentwillfullyappreciatethefundamentallimitationsofpotentialflowasthatsubject isdeveloped.Theauthorhaslivedlongenoughtorealizethatthisorderingofthematerial willnotbetoeveryone’staste,buthemakesnoapologyforthischoice.

Thiscaveataside,thefirsthalfthebook,inChapters1→7,followsarathertraditional route,coveringtopicsmetinmostundergraduatecoursesinengineeringandapplied mathematics.ThisincludestheinviscidequationsofEulerandBernoulli,theNavier–Stokes equationandsomeofitssimplerexactsolutions,laminarboundarylayersandjets,potential flowtheorywithitsvariousapplicationstoaerodynamics,thetheoryofsurfacegravity waves,andflowswithnegligibleinertia,suchassuspensions,lubricationlayers,andthin films.Throughout,acloselinkismaintainedbetweentheoryandapplications.

Thesecondhalfofthebookismorespecializedandhasoneeyetotheneedsofpostgraduatestudentsinengineering,appliedmathematics,andphysics.Vortexdynamics,which issoessentialtomanynaturalphenomena,isdevelopedinChapter8.Thisisfollowedby chaptersonstratifiedfluidsandflowssubjecttoastrongbackgroundrotation,bothtopics beingcentraltoourunderstandingofatmosphericandoceanicflows.Instabilitiesandthe transitiontoturbulencearethencoveredinChapters11and12,followedbytwochapterson fullydevelopedturbulence.Thetopicofturbulenceisintegraltomostengineeringcourses, onthegroundsthatturbulenceisbothubiquitousandimportant,butitislesscommonin textsaimedatstudentsofappliedmathematics,perhapsbecausethesubjectisinfamously resistanttomathematicalattack.However,toneglectsuchanimportanttopicistodeny thecentralnatureofeverydayfluidmechanics,andsoagentleintroductiontothisdifficult subjectisprovidedinChapters13and14.

IwouldliketothankallofthoseatOxfordUniversityPresswhoassistedinthepreparationofthisbook,aswellascolleagueswhohelpedsuggestthevariousscientistswhose imagesappearatthestartofeachchapter.Sadly,thoseportraitsareallofmen.However, Iamcertainthatthelegacyofthecurrentandfuturegenerationsoffluiddynamicistswill bemuchmoreevenlybalancedintermsofgender.Finally,Imustthankmylong-suffering wife,Catherine,forherenduringpatience.

Cambridge,2021

PeterDavidson

1.3.2Bernoulli’sEquationandMechanicalEnergyConservation

1.3.6MoreonMomentumConservation:InviscidFlowThrough aCascadeofBlades

1.4.1TheBorda–Carnot‘HeadLoss’inaSuddenPipeExpansion

2.2.1TwoThingsthatHappentoaFluidElementasitSlidesdownaStreamline

2.2.2TheRate-of-strainTensorandtheDeformationofFluidElements

2.2.3Vorticity:theIntrinsicSpinofFluidElements

2.4.1Newton’sLawofViscosity

2.4.2TheNavier–StokesEquationandtheReynoldsNumber

2.4.3Navier–StokesasanEvolutionEquationfortheVelocityField

2.4.4TheViscousDissipationofMechanicalEnergy

2.5TheMomentumEquationforViscousFlowinIntegralForm

2.6TheRoleofBoundariesandPrandtl’sBoundary-layerEquation

2.6.1TheNeedforBoundaryLayersatHighReynoldsNumber

2.6.2ChangesinFlowRegimeastheReynoldsNumberIncreases

2.7FromLineartoAngularVelocity:VorticityanditsEvolutionEquation

2.7.1TheBiot–SavartLawAppliedtoVorticity:anAnalogywith Magnetostatics

2.7.2TheVorticityEvolutionEquation

2.7.3WheredoestheVorticitycomefrom?

2.7.4EnstrophyanditsGoverningEquation

2.7.5AGlimpseatPotential(VorticityFree)FlowanditsLimitations

2.8Summingup:RealversusIdealFluidMechanics

3SomeElementarySolutionsoftheNavier–StokesEquation ..........

3.1SomeSimpleLaminarFlows

3.1.1PlanarViscousFlow

3.1.2TheBoundaryLayernearaTwo-dimensionalStagnationPoint

3.2TheDiffusionofVorticityfromaMovingSurface

3.2.1TheImpulsivelyStartedPlate:Stokes’FirstProblem

3.2.2TheOscillatingPlate:Stokes’SecondProblem

3.3TheNavier–StokesEquationinCylindricalPolarCoordinates

3.3.1MovingfromCartesiantoCylindricalPolarCoordinates

3.3.2Hagen–PoiseuilleFlowinaPipe

3.3.3RotatingCouetteFlow

3.3.4TheDiffusionofaLong,Thin,CylindricalVortex

3.3.5AThinFilmonaSpinningDisc

3.3.6TheAzimuthal–poloidalDecompositionofAxisymmetricFlows

4FlowswithNegligibleInertia

4.1MotionatLowReynoldsNumber:StokesFlow

4.1.1TheGoverningEquationsatLowReynoldsNumber

4.1.2FlowpastaSphereatLowReynoldsNumber

4.1.3TheOseenCorrectionforFlowoveraSphereatLowRe

4.1.4TheUniquenessandMinimumDissipationTheoremsforLow-ReFlows

4.1.5Two-dimensionalFlowinaWedgeatLowReynoldsNumber

4.1.6Suspensions

4.1.7TheSubtletiesofSelf-propulsionatLowReynoldsNumber

4.2LubricationTheory

4.2.1TheApproximationsandGoverningEquationsofLubricationTheory 105

4.2.2Reynolds’AnalysisoftheSlipperBearing

4.2.3Sommerfeld’sAnalysisoftheJournalBearing

4.2.4Rayleigh’sAnalysisoftheSteppedBearing

4.3ThinFilmswithaFreeSurface

4.3.1ApproximationsandGoverningEquations

4.3.2TheGravity-drivenSpreadingofaCircularPool

4.3.3AFilmonanIncline

4.3.4AThinFilmonaRotatingDisc(Reprise)

5LaminarFlowatHighReynoldsNumber

5.1Prandtl’sBoundaryLayerandaRevolutioninFluidDynamics

5.2TheArchetypalBoundaryLayer:aFlatPlateAlignedwitha UniformFlow

5.3AGeneralizationofPrandtl’sBoundaryLayertoOtherPhysicalSystems

5.3.1APopularModelProblemandtheConceptofMatched AsymptoticExpansions

5.3.2Prandtl’sGeneralizationoftheBoundaryLayer:Another ModelProblem

5.4TheEffectsofanAcceleratingExternalFlowonBoundary-layer Development

5.4.1TheFalkner–SkanSolutionsforFlowoveraTwo-dimensionalWedge

5.4.2TheBoundaryLayerneartheForwardStagnationPointofa CircularCylinder

5.5Jeffery–HamelFlowinaConvergentorDivergentChannel

5.6Boundary-layerSeparationandPressureDrag

5.7ThermalBoundaryLayers

5.7.1ForcedConvection

5.7.2FreeConvection

5.8SubmergedLaminarJets

5.8.1TheTwo-dimensionalJet

5.8.2TheAxisymmetricJet

6.1SomeElementaryIdeasinPotentialFlowTheory

6.1.1ThePhysicalBasisfor,andDangersof,PotentialFlowTheory

6.1.2TheRetrospectiveApplicationofNewton’sSecondLaw: BernoulliRevisited

6.1.3SomeSimpleExamplesofTwo-dimensionalPotentialFlow

6.1.4D’Alembert’sParadox

6.2TheKinematicsofTwo-dimensionalPotentialFlow

6.2.1TheComplexPotential

6.2.2SomeElementaryExamplesoftheComplexPotential

6.2.3FlowNormaltoaFlatPlateofFiniteWidth

6.2.4ANotsoSimpleExample:theIntaketoaSubmergedDuct

6.2.5TheMethodofImagesforPlaneandCylindricalBoundaries

6.3TheLiftForceExertedonaBodybyaUniformIncidentFlow

6.3.1Two-dimensionalFlowoveraCylinderwithCirculation: anIllustrativeExample

6.3.2FlowoveraPlanarBodyofArbitraryShape:theKutta–Joukowski LiftTheorem

6.3.3Kelvin’sCirculationTheorem

6.3.4TheRoleofBoundary-layerVorticityinEstablishingCirculation roundanAerofoil

6.3.5TheLiftGeneratedbyaSlenderAerofoil

7SurfaceGravityWavesinDeepandShallowWater

7.1TheWaveEquationandDispersiveversusNon-dispersiveWaves

7.1.1TheWaveEquationandd’Alembert’sSolution

7.1.2TwoClassesofWaves:DispersiveversusNon-dispersiveWaves 187

7.2Two-dimensionalSurfaceGravityWavesofSmallAmplitude

7.2.1SurfaceGravityWavesonWaterofArbitraryDepth

7.2.2Shallow-waterandDeep-waterWaves

7.2.3ParticlePaths,StokesDrift,andEnergyDensityinDeep-waterWaves

7.2.4WaveDraginDeepWater

7.3TheGeneralTheoryofDispersiveWaves

7.3.1Dispersion,WavePackets,andtheGroupVelocity

7.3.2TheEnergyFluxinaWavePacket

7.4TheDispersionofSmall-amplitudeSurfaceGravityWaves

7.4.1TheGroupVelocityandEnergyDensityforWavesonWater ofArbitraryDepth

7.4.2WavesApproachingaBeach

7.4.3TheInfluenceofSurfaceTensiononDispersion

7.5Finite-amplitudeWavesinShallowWater

7.5.1TheInviscidShallow-waterEquations

7.5.2Finite-amplitudeWavesandNon-linearWaveSteepening

7.5.3TheSolitaryWave1:Rayleigh’sSolution

7.5.4SolitaryWaves2:TheKdeVEquation

7.5.5MoreGeneralSolutionsoftheKdeVEquation:CnoidalWaves

7.5.6TheHydraulicJumpRevisited

8.2InviscidVortexDynamics

8.2.1TheClassicalTheoriesofHelmholtzandKelvin

8.2.3Steady,AxisymmetricFlowsandtheSquire–LongEquation

8.2.4ViscousversusInviscidVortexDynamics

8.3AQualitativeOverviewofsomeSimpleIsolatedVortices

8.3.2AGlimpseatVortexRings

8.3.3VorticesduetoBoundary-layerSeparation

8.3.4ColumnarVorticesintheAtmosphereandOceans

8.4ViscousVortexDynamicsI:thePrandtl–BatchelorTheorem

8.4.1ThePhysicalOriginsofthePrandtl–BatchelorTheorem

8.4.2AProofoftheTheorem

8.5ViscousVortexDynamicsII:Burgers’Vortex

8.5.1ADilemmainTurbulence:FiniteEnergyDissipationfor VanishingViscosity

8.5.2Burgers’AxisymmetricVortex

8.5.3TheRobustNatureofBurgers’Vortex

8.6MoreAxisymmetricVortices(bothViscousandInviscid)

8.6.1Hill’sSphericalVortex

8.6.2TheVelocityFieldandKineticEnergyofaThinVortexRing

8.7ViscousVortexDynamicsIII:theImpulseofLocalizedVorticityFields

8.7.1TheFarfieldofaLocalizedVorticityDistribution

8.7.2TheSpontaneousRedistributionofMomentuminSpace

8.7.3ConservationofLinearImpulseanditsRelationship toLinearMomentum

8.7.4ConservationofAngularImpulseanditsRelationship toAngularMomentum

8.7.5AxisymmetricExamplesofImpulseandVortexRingsRevisited

9.1TheBoussinesqApproximationandaSecondDefinitionofthe FroudeNumber

9.2TheSuppressionofVerticalMotion:aSimpleScalingAnalysis

9.3ThePhenomenonofBlocking

9.4.1LinearLeeWavesinTwoDimensions

9.4.2Finite-amplitudeLeeWavesinTwoDimensions

9.5InternalGravityWavesofSmallAmplitude

9.5.1LinearTheoryandSimpleExamples

9.5.2TheReflectionofInternalGravityWaves

9.6GeneralizedVortexDynamics:Bjerknes’TheoremandErtel’s

10.1Rayleigh’sStabilityCriterionforInviscid,SwirlingFlow

10.2TheEquationsofMotioninaRotatingFrameofReference

10.2.1TheCoriolisForceandtheRossbyNumber

10.2.2RapidRotation:theTaylor–ProudmanTheoremandDrifting TaylorColumns

10.3InertialWavesofSmallAmplitude

10.3.1TheirDispersionRelationship,GroupVelocity,andSpatialStructure

10.3.2TheFormationofTransientTaylorColumnsbyLow-frequencyWaves

10.3.3TheSpontaneousFocussingofInertialWavesandtheFormation ofColumnarVortices

10.3.4HelicityGenerationandHelicitySegregationbyInertialWaves

10.3.5Finite-amplitudeInertialWaves

10.5EkmanBoundaryLayersandEkmanPumping

10.5.1ConfinedSwirlingFlows:theSolutionsofKármán,Bödewadt, andEkman

10.5.2EkmanLayersasaMechanismforEnergyDissipation

10.6TropicalCyclones

10.6.1TheAnatomyofaTropicalCyclone

10.6.2ASimpleModelofa‘Dry’Cyclone

11.1TheCentrifugalInstability

11.1.1Rayleigh’sInviscidCriterionforAxisymmetricDisturbances

11.1.2Two-dimensionalInviscidDisturbances(Rayleighagain)

11.1.3ViscousInstabilityandTaylor’sAnalysis

11.1.4TheExperimentalEvidence

11.2TheStabilityofaFluidHeatedfromBelow

11.2.1Rayleigh–BénardConvection

11.3TheStabilityofParallelShearFlows

11.3.1Rayleigh’sInflectionPointTheoremforInviscid,RectilinearFlow

11.3.2TheSubtleEffectsofViscosity

11.4TheKelvin–HelmholtzInstability

11.4.1TheInstabilityofanInviscidVortexSheet

11.5TheStabilityofContinuouslyStratifiedShearFlow

11.5.1TheTaylor–GoldsteinEquationforFluctuationsinaStratified ShearFlow

11.5.2TheRichardsonNumberCriterionfortheStabilityofaStratified ShearFlow

11.5.3AnInterpretationoftheStabilityCriterionintermsofEnergy

11.6TheKelvin–ArnoldVariationalPrincipleforInviscidFlows

11.6.3SomeSimpleApplicationsoftheTheorem

11.7AVariationalPrincipleforInviscidFlowsbasedontheLagrangian

11.8TheStabilityofPipeFlow:aQualitativeDiscussion

12TheTransitiontoTurbulenceandtheNatureofChaos

12.1SomeCommonThemesintheTransitiontoTurbulence

12.3TheNatureofChaos:theLogisticMapasanExample

13.1ElementaryPropertiesofTurbulence:aQualitativeOverview 391

13.1.1TheNeedforaStatisticalApproachandtheProblemofClosure

13.1.2TheVariousStagesofDevelopmentofFreelyDecayingTurbulence 394

13.1.3Richardson’sEnergyCascade

13.1.4TheRateofDestructionofEnergyandanEstimate ofKolmogorov’sMicroscales

13.2ADigressionintotheKinematicsofHomogeneousTurbulence

13.2.1TwoUsefulDiagnosticTools:CorrelationFunctionsand

13.2.2TheSimplificationsofIsotropyandtheTaylorScale

13.2.3Scale-by-scaleEnergyDistributionsinFourierSpace:the EnergySpectrum

13.2.4RelatingReal-spaceandSpectral-spaceEstimatesof theEnergyDistribution

13.2.5ACommonErrorintheInterpretationofEnergySpectra

13.3Kolmogorov’sUniversalEquilibriumTheoryoftheSmallScales(K41)

13.3.1DoesSmall-scaleTurbulencehaveaUniversal,IsotropicStructure atLargeRe?

13.3.2Kolmogorov’sUniversalEquilibriumTheory:theTwo-thirdsand Five-thirdsLaws

13.3.3TheKármán–HowarthEquation

13.3.4Kolmogorov’sFour-fifthsLaw

13.3.5Obukhov’sConstantSkewnessClosureModel

13.4SubsequentRefinementstoK41

13.4.1Landau’sObjectiontoK41BasedonLarge-scaleIntermittency oftheDissipation

13.4.2Kolmogorov’s1961RefinementofK41basedonInertial-range Intermittency

13.5TheProbabilityDistributionoftheVelocityField

13.5.1TheSkewnessandFlatnessFactors

13.5.2TheFlatnessFactorasaMeasureofIntermittency

13.5.3TheSkewnessFactorasaMeasureofEnstrophyProduction

14.1ReynoldsStresses,EnergyBudgets,andtheConceptofEddyViscosity

14.1.1ReynoldsStressesandtheClosureProblem(Reprise)

14.1.2TheEddyViscosityModelofBoussinesq,Taylor,andPrandtl

14.2TheTransferofEnergyfromtheMeanFlowtotheTurbulence

14.3TurbulentJets

14.4TurbulentFlownearaSmoothBoundary:theLog-lawoftheWall

14.4.1TheLog-lawoftheWallinChannelFlow

14.4.2TheLog-lawandViscousSublayerforOtherSmooth-walledFlows

14.4.3InactiveMotion:aProblemfortheUniversalityoftheLog-law?

14.4.4EnergyBalancesandStructureFunctionsintheLog-lawLayer

14.4.5CoherentStructuresandNear-wallCycles 466

14.4.6TurbulentHeatTransfernearaSurfaceandtheLog-law forTemperature

14.5TheInfluenceofSurfaceRoughnessandStratification onTurbulentShearFlow 472

14.5.1TheLog-lawforFlowoveraRoughSurface 472

14.5.2TheAtmosphericBoundaryLayer,Stratification,andtheFlux RichardsonNumber

14.5.3Prandtl’sWeak-shearModeloftheAtmosphericBoundaryLayer

14.5.4TheMonin–ObukhovTheoryoftheAtmosphericBoundaryLayer

14.6ClosureModelsforTurbulentShearFlows:the

3Navier–StokesEquationinCylindricalPolarCoordinates

PROLOGUE

Thescopeoffluidmechanicsisvast,findingamultitudeofapplicationsinbiology,engineering,meteorology,geophysics,andastrophysics.Moreover,theseflowsvaryenormously inscale,withcharacteristiclength-scalesthatrangefrom0.001mm(swimmingbacteria) to1010 km(protoplanetaryaccretiondiscs)andvelocitiesthatvaryfrom0.1mm/s(convectioninthemoltencoreoftheEarth)to100km/s(theeruptionofasolarflare).Afew randomlychosenexamplesareshowninthetablebelow,arrangedmoreorlessbythescale ofthemotion.

TheClassofFlow TypicalScale

Theswimmingofmicroorganismssuchasbacteriaandsperm

Lubricationlayersinbearings

Therustlingofleaves,theflightofinsects,andthematingcallofmice1mm→1cm

Thefluiddynamicsofplanes,trains,andautomobiles 10cm→30m

Tidalvorticesintheoceansanddustdevilsindeserts 1m→10m

Flowdownthespillwayofadam 2m→30m

Vortexrings(smokerings)producedbyvolcaniceruptions 50m

Leewavesbehindmountainranges 1km

Tropicalcyclones 100km→103 km

ConvectioncellsinthemoltencoreoftheEarth 103 km

Large-scaleoceangyres 103 km→104 km

Aprotoplanetaryaccretiondiscrotatingaroundayoungstar 1010 km

Weoftenthinkoffluidmechanicsasbelongingtothedomainofengineering,anditis truethatitiscentraltomuchofmechanicalengineering(forexampleinlubricationtheory, naturalandforcedconvection,combustion,andpowergeneration),andtomuchofcivil engineering(riversandcanals,dams,surfacegravitywaves,coastalerosion).Italsoliesatthe heartofchemicalengineeringandaerodynamics.However,thereareprobablyjustasmany applicationsoutsideengineering.Forexample,inbiologyfluiddynamicsfindsapplications inthestudyofthecardiovascularsystem,respiratorydisorders,theswimmingoffishand micro-organisms,andintheflightofinsectsandbirds.Fluidmechanicsalsodominates ourstudyoftheatmosphereandtheoceans,includingtopicssuchasurbandispersion,the dispersalofpollutantsintheoceans,meteorology(includingextremeeventsliketornadoes andtropicalcyclones),andthelarge-scaleatmosphericandoceanicflowsthatcontrolthe weather.Evenastrophysicistscannotavoidthesubject,asitiscentraltosuchtopicsas magneticfieldgenerationwithintheconvectiveinteriorsofplanetsandstars,theviolent activityatthesurfaceoftheSun(solarflaresandcoronalmassejections),thesolarwind,

andthespirallingmotionwithinthosevastaccretiondiscsthatsurroundyounganddying stars.Itishardnottobeintriguedbyasubjectthatpervadessomanyaspectsofourlives.

Unfortunately,givenitscentralimportanceinsomanybranchesofscienceandtechnology,fluiddynamicsisnotaneasysubject,andattheheartofthatdifficultyliesthefactthat thegoverningequationsare non-linear.Itisalltooeasytounderestimatetheimportance ofthisstatement.Mostcommon linear partialdifferentialequations(PDEs)arephysically wellbehavedandsoarerelativelyeasytosolveanalytically.Indeed,inagivensituation, onecanoftendivinethephysicalcontentofalinearPDEwithouthavingtosolveitin anygreatdetail,byinvokingsuchconceptsasdiffusionlength,Green’sinversionintegral (theBiot–Savartlaw),ortheideasofgroupvelocityandwavedispersion.So,insubjects suchaselectrodynamicsorelasticity,wherethegoverningequationsarelinear,thereare hundreds,ifnotthousands,ofexact,non-trivialsolutions,andthereexistreferencebooks whosefunctionistosimplycataloguethiscornucopiaofexactsolutions.Influiddynamics, ontheotherhand,weknowofnomorethanacoupleofdozenexact,non-trivial,nonlinearsolutionsofthegoverningequations.(Iexcludehereinviscidpotentialflows,whose lineargoverningequationsreallybelongtotheworldofkinematicsratherthandynamics, asweshallsee.)Oneconsequenceofthedifficultyoffindingclosed-formsolutionsin fluidmechanicsisthatgreatemphasisisplacedontheroleofconservationprinciples andconservedquantities.Thehope,ofcourse,isthattheseconservationprincipleswill constrainthebehaviourofaflowsufficientlyforitsessentialfeaturestobeestablished. Thereisasecondconsequenceofnon-linearity,overandaboveadearthofclosedformsolutions.Unlesstheyareheavilydamped,non-linearsystemstendtoexhibitnonuniquenessandhysteresis,andsoitiswithfluidmechanics.Worsestill,ifthedampingissufficientlyweak,manynon-linearsystemsdevelopchaoticbehaviour,withallthecomplexities whichthatentails.Influidmechanicsthatchaosmanifestsitselfas turbulence,whichisthe naturalstateofnearlyallflowsinengineeringandappliedphysics.Whilearaindroprunning downawindowpanemaybelaminar(non-turbulent),thewindinthestreetoutside,the flowofwateroutofatap,andeventheflowofairinandoutofourlungs,areallexamples ofturbulentmotion.Inshort,turbulenceisthenormandnottheexception,andweare stilltryingtocometotermswiththecomplexitiesofturbulence.Indeed,thegreatEnglish appliedmathematicianHoraceLambisreputedtohavesaid:

Iamanoldmannow,andwhenIdieandgotoheaventherearetwomattersonwhichI hopeforenlightenment.Oneisquantumelectrodynamicsandtheotheristheturbulent motionoffluids.AbouttheformerIamratheroptimistic.(AttributedtoLambbySidney Goldstein,1932.)

Littlehaschanged.Turbulenceremainstothisdayaprofoundlydifficulttheoretical problemandweshallhavemuchmoretosayaboutitinduecourse.

Onereactiontothedifficultyofmakinganalyticalprogressinfluidmechanicshasbeena strongdrivetowardsnumericalsimulations,orperhapsweshouldsaynumericalexperiments Inmanysensesthishasbeenamajorsuccessstory,fuelledbythefactthatcomputing powerhasrisensorelentlessly.Aswithlaboratoryexperiments,thecarefuluseofnumerical simulationsasasourceofinformationcanprovidevaluableinsights,althoughofcoursethe

Figure1 Theself-induced,centrifugalburstingofaninviscid,axisymmetric,swirlingbloboffluid.

(a)Theinitialconditionconsistsofazimuthalmotion, uθ,only.(b)Asecondaryflow, up,develops whichsweepstheangularmomentumcontours, Γ =const.,radiallyoutward.(c)Theangular momentumcontoursformathinsheetandthefinalasymptoticstatetakestheformofamushroomshapedvortexsheetwhichthinsexponentiallyfast.

abilitytocomputeaflowisnosubstituteforunderstandingit.Numericalexperimentshave proventobeparticularlyimportantinthedifficultfieldofturbulence,andindeedtheyhave becometheresearchtoolofchoiceformanytheoreticians.However,theaccuratesimulation ofevensimpleflowsisnotalwaysasstraightforwardasonemightthink,asthefollowing rathertrivialexampleillustrates.

Consideraninviscid,axisymmetricflowwhoseinitialvelocityfieldis ur = uz =0 and uθ =Ωr exp( x2/δ2) incylindricalpolarcoordinates(r, θ, z).Thatistosay,theinitial flowissimplyaswirlingboboffluidcentredontheoriginandwhoseangularvelocityfalls offasaGaussianonthescaleof δ.Itisconvenienttointroducethenotation Γ= ruθ for theangularmomentumdensityaboutthe z-axisand up =(ur, 0,uz) forthesecondary (poloidal)motioninthe r–z plane.Wenowtreatthisasaninitial-valueproblemand integrateforwardintime,retainingaxialsymmetry.Giventhesmoothinitialconditions, onemighthaveexpectedthatanumericalsimulationofthissimpleflowwouldbestraight forward,butitisnot.Itturnsoutthattheswirlingfluidwantstocentrifugeitselfradially outward,anditdoesthisbycreatingasecondarypoloidalvelocityfield, up.Italsohappens thatthelinesofconstantangularmomentummovewiththefluid,asifeachatomwants toholdontoitsinitialvalueof Γ,andsothesecondaryflow, up,sweepsthecontoursof constant Γ radiallyoutward,asshowninFigure1.Sofarthereisnothingunusual.However, beforelongtheangularmomentumcontoursgetsweptuptoformathin,axisymmetric, mushroom-shapedvortexsheet,andthatsheetthenstartstothinexponentiallyfast,as discussedinExercises8.1and11.6.

Mostnumericalschemesnowrapidlyrunintotrouble,asitisextremelydifficulttoretain adequatespatialresolutionofavortexsheetthatthinsexponentiallyfast.Someschemes becomenumericallyunstableastheyloseresolution,whileothersartificiallysmearoutthe sheet,thusproducingerroneousresults.Yetotherschemestrytoretainbothaccuracyand stabilitybycontinuouslyrefiningthespatialresolution,butthisquicklycausesthetimestep requiredfornumericalstabilitytobecomeintolerablyshort.Clearly,noneoftheseoutcomes

issatisfactoryandthatsuchaformidablenumericalproblemcanemergefrombenigninitial conditionsgivesonecausetoreflect.

Thereisasecondconsequenceofthedifficultyofmakinganalyticalprogressinfluid dynamics,whichistheneedtomakeextensiveuseofdimensionalanalysis.Famously,dimensionalanalysishasbeencaricaturedasaprocedurebywhichonecanestablishthe scaling lawswhichgovernsomephysicalprocesswithoutanyunderstandingofthephenomenonin question.Perhapsthisissomewhatofanexaggeration,butitdoesatleasthighlightboththe powerofthemethodandthedisconcertingthoughtthat,incertainsituations,scalinglaws canbeestablishedwithminimalphysicalunderstanding.

Letusconsiderasimpleexample.Supposeweareinterestedinsurfacegravitywavesof wavelength λ propagatingacrossdeepwater,andwehave(somehow)decidedthatneither surfacetensionnorviscosityareimportantforthisparticularclassofwaves.Wemight thenask:howdoestheangularfrequencyofthesewaves, ϖ,dependontheirwavelength?

Detailedandnontrivialanalysis(eventually)showsthattheansweris ϖ = √2πg/λ, where g istheaccelerationduetogravity,asdiscussedinChapter7.However,thescalinglaw ϖ ∼ √g/λ canbeobtainedmuchfasterthroughsimpledimensionalconsiderations.The argumentproceedsasfollows.Weaskwhatphysicalparameters ϖ mightdependon,andthe answeristhat,sincewaveamplitudeshouldnotberelevantforalineartheory,andwehave excludedsurfacetensionandviscosity,theonlyrelevantquantitiesleftare λ and g.Wethen notethat ϖ, λ,and g containbetweenthemonlytwodimensions:lengthandtime,andso wewrite P =3 (forthreeparameters)and D =2 (fortwodimensions).The Buckingham Pitheorem thentellsusthatthenumberofdimensionlessgroups, G,thatwecanformfrom ϖ, λ,and g is G = P D =1,asdiscussedinAppendix1.Next,wenotebyinspection thatthisdimensionlessgroupcanbewrittenas Π= ϖ√λ/g.However,onedimensionless groupcandependonlyonanotherdimensionlessgroup,andinthiscasetherearenoother groupsavailabletous.So Π issimplyaconstantandthescalinglaw ϖ ∼ √g/λ follows.Of course,thisisarathertrivialexample,andtheapplicationofdimensionalanalysistomore complexproblemsisrarelysostraightforward.Nevertheless,itisthecasethat,inthehands ofanexpert,dimensionalanalysisprovidesaparticularlypowerfultool.

Onthatfinalnote,perhapsitistimetobringthisprologuetoacloseandinvitethereader toimmersethemselvesinatopicfullofsurprises.

ElementaryDefinitions,SomeSimple Kinematics,andtheDynamics

1.1ElementaryDefinitions

1.1.1WhatistheMechanicalDefinitionofaFluid?

Theanswertothisquestionmayseemtriviallyobvious,butitturnsouttobeworth pondering.Theterm fluid encompassesbothliquidsandgases,theformerbeingcharacterizedbytheexistenceofafreesurfaceandthelatterbytheeasewithwhichitmaybe compressed.Somewhatsurprisingly,themacroscopicdynamicsofbothliquidsandgases canbeaccountedforbymoreorlessthesametheory,withonlymodestdifferencesin emphasis.

Toconstructsuchatheoryweadoptthe continuumapproximation,whichassumesthat matterissmearedcontinuouslyacrossspace.Thisapproximationrestsonthelargedifferencebetweenthemolecularscale(thedistancebetweenmolecules)andthecharacteristic distanceoverwhichthe macroscopic propertiesofafluid,suchasdensityorpressure,vary. So,forexample,thedensityofafluidisdefinedasthemassperunitvolumemeasured overascalewhichislargeenoughforallmolecularfluctuationstobesmoothedout,yet smallenoughforthedensity, ρ,tobeconsideredasmoothlyvaryingfunctionofposition. Likewise,thestressesexertedbyonepartofafluidonanotherareconsideredtobeasmooth functionofposition,beingdefinedastheforceperunitareatransmittedacrossasmallplane surfacewithinthefluid,thesurfacebeinginfinitesimallysmallonthemacroscopicscale,yet largeonthemolecularscale.Thesemaybenormalstresses,arisingfromforcesperpendicular tothesurfaceinquestion,orshearstresses,arisingfromtangentialforces.

Thedistinctionbetweensolidsandfluidsis,atfirstsight,ratherobvious; i.e. solids exhibitrigidity,whilefluidsreadilydeformwhenacteduponbyaforce.However,there aresubtletiesinthisdistinctionthatareworthnoting.Forexample,wecannotdistinguish betweensolidsandliquidsifonlynormalstressesareinplay.Rather,itisthewayinwhich thesetwostatesrespondtoanimposed shearstress thatdistinguishesbetweenthetwo. Suppose,forexample,thatwehavetwocylinders,eachsealedbyamovablepiston.One cylinderisfilledwithoilandtheotherwithacylindricalblockofrubber.Wenowpressurize thecontentsofthetwocylindersusingthepistons.Evidentlybothsystemsbehaveinexactly thesameway:whenacompressivestressisimposedbythepistons,boththeoilandthe rubbercompressalittle,andthenreturntoastateofstaticequilibrium.

Nowconsideradifferentarrangement,consistingoftwolargeflatmetalplateswhichlie paralleltoeachotherandareseparatedbyasmallgap, d.Thebottomplateisfixedandthe toponeisfreetoslide,asshowninFigure1.1.Supposewehavetwosuchpairsofplates, d y u( y) Oil

Figure1.1 Thegap d betweentwoplatesisfilledwithoilandtangentialforcesestablishashear stress, τ ,withintheoil.Thisstresscauseslayersofoiltoslideoveroneanother.

andinonecasewefillthegapwithoilandintheotherthegapisfilledwitharubbersheet thatisbondedtothemetalplates.Wenowapplyequalandoppositetangentialforces, F,to thetwoplates,whichestablishashearstress, τ ,inboththeoilandtherubber.Thereisnow acleardifferenceinbehaviour.Therubberbehavesexactlyasbefore,givingalittlewhen thestressisfirstapplied,butthenremaininginequilibriumthereafter.Theoil,ontheother hand,behavesdifferently.Itstickstothetopandbottomplatesand,foraslongastheshear stressisapplied,layersofoilslideovereachother.Staticequilibriumisre-establishedonly whenthestressisremoved.Thisdifferenceinbehaviourprovidesthedefinitionofafluid: a fluid,unlikeasolid,continuouslydeformsundertheactionofashearstress.Thereisanimportant corollarytothis,whichis: ifafluidisinstaticequilibrium,theshearstresseswithinitmustbe zeroeverywhere

Figure1.1alsoservestointroduceanotherimportantpropertyofallfluids:thatof viscosity.Supposethat y isthedistancefromthelowerplate, V thespeedofthetopplate, and u(y) thedistributionofhorizontalvelocityofthefluid.Itisobservedthat,fornearlyall commonfluids,thevelocitygradient, du/dy = V /d,isproportionaltotheappliedshear stress, τ .Thisis Newton’slawofviscosity anditiswrittenintheform

wheretheconstantofproportionality, µ,isthe dynamicviscosity ofthefluid,andtherelated property, ν = µ/ρ,isknownasthekinematicviscosity.Somefluidsareclearlyviscous,others lessobviouslyso,butitisimportanttorealizethat all fluids(exceptsuperfluidhelium) have some viscosity,eveniftheyappeartobevery‘thin’.Indeed,thekinetictheoryofgases explicitlypredictsthatthekinematicviscosityisproportionaltotheproductofthemean freepathlengthandthemeanthermalvelocityofthemolecules.

Actually,notallsubstancescanbeclassifiedassimplyassuggestedabove.Forexample,on shorttimescalesasphaltbehaveslikeasolid.Youcanwalkonitwithoutleavingfootprints, andifstruckbyahammeritshatterslikeglass.Ontheotherhand,ifsubjectedtoforces forlongperiodsoftime(years),asphaltflowscontinuouslylikeafluid.Moreover,some thixotropicsubstancesbehavelikeanelasticsolidifallowedtosettleforlongenough,yet flowlikeafluidifsubjecttosignificantstresses.Weshallnotconsidersuchcomplexfluids inthisbook.

1.1.2FluidStaticsandOneDefinitionofPressure

Beforediscussingthedynamicsoffluids,perhapsitisworthmakingafewcommentsabout hydrostatics,ifonlytoreinforcethenotionsofpressureandofstressesactingwithinafluid. Letusstartwith Pascal’slaw forstationaryfluids.

Wehavealreadyseenthatshearstressesareeverywherezeroinastationaryfluid.Pascal’s lawfollowsdirectlyfromthisandstatesthatthemagnitudeofthenormalstressactingatany givenpointisindependentofdirection.Theproofistrivial.Letususe σ todenoteanormal stressandreserve τ forshearstress.Considerasmallwedgeoffluidofmass m surrounding thepointofinterest,asshowninFigure1.2.Letthewedgehavesides δx, δy,and δz,andlet

Figure1.2 Forcesactingonawedgeofstaticfluidarisingfromthenormalstresses.

σx, σz,and σα bethenormalstressesinthe x and z directionsandontheinclinedsurface.

Astherearenoshearstresses,verticalequilibriumdemands

andasthesizeofthewedgetendstozerotheweight mg dropsoutof(1.2)togive

σα = σz.Similarly,horizontalequilibriumrequires σα = σx.So,weconcludethatbecause oftheabsenceofshearstress,thenormalstress, σ,isthesameinalldirections.Influid dynamicsthenormalstressesarecompressive,andsowedefinethefluidpressuretobe p = σ,andPascal’slawissometimesparaphrasedassayingthat thepressureatanygiven pointisthesameinalldirections.

Perhapssomecommentsareinorder.First,themechanicalpressureasdefinedaboveis thesameasthethermodynamicpressure.Second,sometimesitisconvenienttopretend thatafluidhaszeroviscosity(aso-called idealfluid),inwhichcasetherearenoviscous stresseswithinthefluidwheninmotion.Onceagaintheshearstressesvanishandthenormal stressatanygivenpointisthesameinalldirections.(Notethatanyinertialforcevanishes toleadingorderinalocalforcebalancelike(1.2),justastheweightdropsoutof(1.2)as thevolumeofthefluidelementgoestozero.)Forahypotheticalinviscidfluid,then,the mechanicalpressureisonceagainsimplydefinedas p = σ,whetherthatfluidisstationary orinmotion.Conversely,ifa real fluidisinmotionthere will,ingeneral,beshearstresses actingwithinthefluid.Thenormalstressesatagivenpointthendependondirectionand itismeaninglesstodefinemechanicalpressureinthisway.Weshallreturntothispointin Chapter2,wherewerefineourdefinitionofpressure.

Letusnowreturntohydrostaticsandgotothenextorderinourforcebalance,gathering termsoforder δxδyδz.Wemustnowallowforspatialgradientsinpressureifwewant tobalancetheweightofasmallfluidelement.Theeasiestwaytoseethisistoconsider thecylindricalelementoffluidshowninFigure1.3,ofcross-sectionalarea A,mass m,and height δz.Clearlythepressureatthebottomoftheelementmustexceedthatatthetopin ordertobalancetheweightofthefluidinbetween.Indeed,averticalforcebalancerequires

Thehorizontalgradientsinpressure,bycontrast,arezero,andsoournethydrostaticforce balanceis

Figure1.3 Theverticalforcebalanceforacylindricalelementinastationaryfluid.

p = ρg,

where g = g ˆ ez isthegravitationalacceleration.

Thereisamoremathematicalwayofgettingtothesameresultthatisworthoutlining, asweshalldosomethingsimilarwhenitcomestodynamics.Considerasmallvolume, V , withinthefluidwhichhassurface S andisofarbitraryshape.Thepressureforceexertedby thesurroundingfluidonapartof S,say dS,isthen pdSn = pdS,where n isanoutward pointingunitnormalto S.Thusthetotalpressureforceactingonthefluidwithin V isthe surfaceintegralof p.ThisthenconvertsintoavolumeintegralusingavariantofGauss’ theorem: netpressureforceactingon V = S

Wenowignoresecond-orderderivativesinpressureonthegroundsthat V issmall,sothe netpressureforcebecomes (∇p)V .Sincethisforce,plustheweightofthefluid, ρV g, mustsumtozero,weconcludethat ∇p = ρg,whichbringsusbackto(1.4).

Forthespecialcaseofafluidofuniformdensity,(1.3)integratestogive p = p0 ρgz, where p0 isareferencepressure.Whendealingwith liquids thisisnormallyrewrittenas p = ρgς,where ς isthedepthbelowthefreesurfaceand p isnowinterpretedasgauge pressure, i.e. thepressureoverandaboveatmosphericpressure.Thisreflectsthefactthatan upwardforceperunitareaof p = ρgς isrequiredtobalancetheweight mg =(ρς)g ofan overlyingcolumnoffluid.Thus,forexample,thepressureatthebaseoftheMarianatrench, whichisaround10kmdeep,is108 N/m2,or103 atmospheres.Notethatthepressureforce actingonasubmergedbodyisnowdeterminedbythesurfaceintegral

forceonasubmergedbody = pdS = (ρgς)dS. (1.6)

Inpractice,however,itisofteneasiertouseArchimedes’principletofindthenetpressure forceonsuchabody.Thisstates: ifabodyispartiallyorwhollyimmersedinafluidthenit receivesanupwardpressureforceequaltotheweightofdisplacedfluid,withthatforceacting throughthecentreofgravityofthedisplacedfluid.Readersmaywishtoprovethisprinciple forthemselves.Ifso,notethattheproofrequiresnomathematics.

Letuscloseourdiscussionofhydrostaticswithawhimsicalparadox,devisedbyDen HartogandbasedonArchimedes’principle.ConsiderFigure1.4,whichshowsaboxin