1

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP, United Kingdom

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries

© Suhrkamp Verlag 2021

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

First Edition published in 2021

Impression: 1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Data available

Library of Congress Control Number: 2021935956

ISBN 978–0–19–289819–7

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780192898197.001.0001

Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY

Oxford University Press makes no representation, express or implied, that the drug dosages in this book are correct. Readers must therefore always check the product information and clinical procedures with the most up-to-date published product information and data sheets provided by the manufacturers and the most recent codes of conduct and safety regulations. The authors and the publishers do not accept responsibility or legal liability for any errors in the text or for the misuse or misapplication of material in this work. Except where otherwise stated, drug dosages and recommendations are for the non-pregnant adult who is not breast-feeding

© Suhrkamp Verlag Berlin 2020

All rights reserved by and controlled through Suhrkamp Verlag Berlin

Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. Oxford disclaims any responsibility for the materials contained in any third party website referenced in this work.

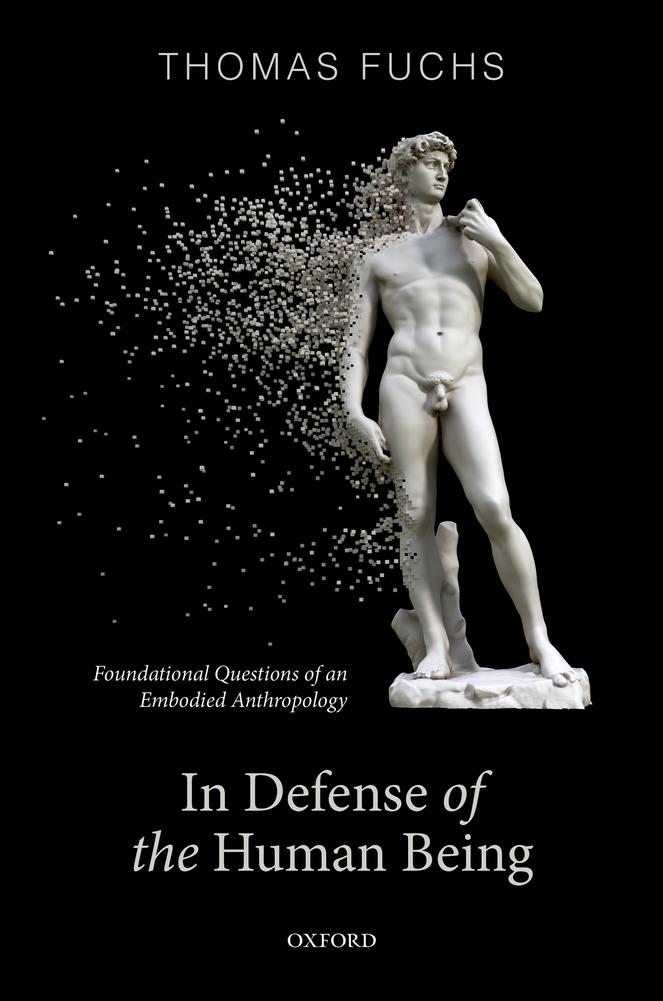

With the progress of artificial intelligence, the digitalization of the life-world, and the reduction of the mind to neuronal processes, the human being appears more and more as a product of data and algorithms. We understand ourselves in the image of our machines, while conversely, we elevate our machines and our brains to new subjects. Against this self-reification of the human being, the philosopher and psychiatrist Thomas Fuchs defends a humanism of embodiment: our corporeality, vitality, and embodied freedom are the foundations of a self-determined existence that uses the new technologies as means instead of submitting to them.

Thomas Fuchs, psychiatrist and philosopher, is Karl Jaspers Professor for Philosophical Foundations of Psychiatry at Heidelberg University and chairs the research section “Phenomenological Psychopathology and Psychotherapy” at the Psychiatric University Hospital Heidelberg.

Abbreviations xi

Introduction: A Humanism of Embodiment 1

Acknowledgments 8

References 8

A Artificial Intelligence, Transhumanism, Virtuality

1 Human and Artificial Intelligence: A Clarification 13

Introduction: The World of Data 13

The Digitization of the World 16

Subjectivity and Its Simulation 20

Persons are Not Programs 24

Programs are Not Persons 28

Robots, Androids, and Artificial Life (AL) 35

Conclusion: Simulation and Original 41

References 45

2 Beyond the Human? A Critique of Transhumanism 49

Introduction: Between Naturalism and Culturalism 49

The Idea of Perfectibility 54

Can Human Nature be Improved? 59

Cognitive Skills 59

Happiness and Morality 61

Aging and Death 64

The Contradictions of Posthumanism 67

Mind Uploading or Transfer of Consciousness 69

Critique of Functionalism 71

Critique of Neuro-Reductionism 74

Transhumanism as Neo-Gnosticism 75

Conclusion 76

References 79

3 The Virtual Other: Empathy in the Age of Virtuality 83

Introduction 83

Empathy and Virtual Reality 86

Primary, Implicit, or Intercorporeal Empathy 86

Extended, Explicit or Imaginative Empathy 87

Fictional Empathy 88

Interim Summary 92

Virtualization in the Present 94

Phantomization 94

Disembodied Communication 96

Summary and Conclusion 98

References 101

B Brain, Person, and Reality

4 Person and Brain: Against Cerebrocentrism 107

Introduction 107

Critique of the Cerebral Subject 109

Subjectivity and Intentionality 109

Embodiment 110

Interpersonality 112

Critique of Localizationism 113

Critique of Neuroimaging 114

Holism of Consciousness 115

Personhood as Embodied Subjectivity 116

Brain, Body, and Environment 116

Brain Transplantation 119

Conclusion 120

References 121

5 Embodied Freedom: A Libertarian Position 124

Introduction 124

Can Brains make Decisions? 126

Freedom as a Personal Ability 128

Embodied Freedom 131

Counter Positions 133

External Objections 133

The Compatibilist Counter Position 136

Immanent Objections 138

Conclusion 141

References 142

6 Brain World or Life World? Critique of Neuroconstructivism 144

Introduction 144

Bodily Being-in-the-World: The Coextension of Lived Body and Physical Body 147

The Locus of Pain 151

Conclusion: Life-World and Neuroscience 153

References 155

7 Perception and Reality: Sketch of an Interactive Realism 157

Introduction 157

Perception as Interaction 159

The Objectifying Power of Perception 162

The Implicit Intersubjectivity of Perception 164

Genesis of Intersubjective Perception 167

Subjectivation of Perception in Schizophrenia 169

Summary 171

References 174

C Psychiatry and Society

8 Psychiatry between Psyche and Brain 181

Introduction 181

Reductionist Assumptions and their Verification 184

Psychiatry as Relational Medicine: An Integrative Concept 188

Conclusion 190

References 192

9 Embodiment and Personal Identity in Dementia 196

Introduction 196

Personal Identity 197

Body Memory 200

Dementia and Personal Identity 203

Dementia as a Loss of Reflexivity and Meta-Perspective 203

Body Memory in Dementia 205

Relational versus Embodied View of the Person in Dementia 209

Conclusion 212

References 213

10 The Cyclical Time of the Body and the Linear Time of Modernity 217

Introduction 217

The Processes of Life and their Cyclical Time 218

The Cyclical Structure of Body Memory 222

Cyclical and Linear Time 225

Individual and Collective Formation of the Linear Order of Time 226

Conflicts between Cyclical and Linear Orders of Time 228

Conclusion 231

References 232

Text References (English papers) 237

Index 239

Introduction: A Humanism of Embodiment

The image of the human being that we hold to be true becomes itself a factor in our lives. It determines the ways in which we deal with ourselves and with other people, it determines our attitude in life and our choice of tasks.

Karl Jaspers (1948: 56)

In Defense of the Human Being this title requires explanation. A defense can be directed against a criticism or accusation, but also against a questioning or a threat. Now, there is a long tradition of putting humanity itself in the dock, accusing humans of immoderateness, greed, hubris, or malice, for the horrors of war or the destruction of the planet. Recently, there have even been many suggestions that it would be best for the planet if it could free itself from its “mold,” as Schopenhauer once called humanity.1 Homo sapiens has abused its supremacy, so the argument runs, and therefore deserves to perish by a collapse of the ecosystem or other catastrophes—or to make way for a superior artificial super-intelligence. At a moment when geologists have already proclaimed the new planetary age of the Anthropocene to describe the comprehensive transformation of the Earth by humans, some argue that it would be better if this age were the shortest of all.2

1 In infinite space countless shining spheres, around every one of them rotate perhaps a dozen illuminated smaller ones, hot within, covered with a solidified, cold rind, on which a moldy covering has produced living and knowing beings:—that is the empirical truth, the real, the world (Schopenhauer 1859/1966: 3).

2 Humanity as the “plague of the planet” is a topos particularly of radical ecological movements; for example, the Voluntary Human Extinction Movement, founded in 1991

In Defense of the Human Being. Thomas Fuchs, Oxford University Press. © Suhrkamp Verlag 2021.

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780192898197.003.0001

An apology for humanity against such misanthropy might be appropriate, but it is not my theme. It is not my concern to defend humanity against an accusation, but against a questioning. Because today, in question is what one could call—with unavoidable imprecision—the humanistic image of man. At the center of this image is the human person as a physical or embodied being, as a free, self-determining being, and ultimately as an essentially social being connected with others. According to this understanding, persons are not mere spirits or monads of consciousness but embodied, living beings. And persons do not exist in the singular but only in a common relational space. In the concept of human dignity, understood as the claim to recognition that human beings raise through their bodily existence and co-existence, the definitions that constitute a humanistic, personal image of humanity culminate and unite.3 To what extent is this self-image of man currently in question?

Beyond Freedom and Dignity is the title of a book published in 1971 by B. F. Skinner, an American behavioral psychologist. Skinner argued that belief in something like free will and moral autonomy was the relic of a mythical, prescientific view of man. The attribution of personal responsibility and dignity impedes scientific progress on its way to conditioning human behavior through appropriate social technology and thus creating a happier society without overpopulation and wars. Skinner’s behaviorist vision has failed to take hold. But his basic idea that science is capable of replacing our self-conception, which is caught up in prejudice and myth, with a rational knowledge of human beings, and with corresponding technologies is more relevant than ever.

In his book Homo Deus (2017), the historian Yuval Noah Harari has sketched out a gloomy scenario for the future, according to which scientific and technological progress will gradually render the liberal and humanistic view of humanity obsolete. According to Harari, we will increasingly surrender to the by Les Knight, advocates the extinction of humanity to save the Earth (cf. their website www.vhemt.org). Robert Ettinger has drawn another, specifically transhumanistic conclusion:

Thus, humanity itself is a disease, of which we must now proceed to cure ourselves [ . . ]. To do this, it must first be shown that homo sapiens is only a botched beginning; when he clearly sees himself as an error, he may not only be motivated to sculpt himself, but to make at least a few swift and confident strokes. (Ettinger 1989: 4, 8f.)

3 Of course, representatives of transhumanism also refer to a “secular humanism” (for example, Bostrom 2005: 202). But, in this interpretation, the term is decoupled from its classical tradition, which goes back to the Renaissance, and is used to designate decidedly atheistic positions that often connect with a reductive naturalism too.

algorithms,4 data analyses, and forecasts of artificial intelligence, as they can already provide better information about the future than our limited human intelligence:

People will no longer see themselves as autonomous beings running their lives according to their wishes, but instead will become accustomed to seeing themselves as a collection of biochemical mechanisms that is constantly monitored and guided by a network of electronic algorithms. (Harari 2017: 334)

Harari, with constant recourse to the biological and cybernetic sciences, and having thoroughly destroyed the foundations of the liberal view of man, nevertheless wants to leave open the possibility that science could be wrong after all: “Is there perhaps something in the universe that cannot be reduced to data?” (Harari 2017: 399). “Are organisms really just algorithms and is life really just data processing?” (Harari 2017: 402). If not, says Harari, then perhaps something could be lost after all if people let themselves be controlled (and in the end even be replaced) by intelligent machines. But after all Harari’s fatalistic remarks this is no more than a façon de parler. For him it remains the case that “Homo sapiens is an obsolete algorithm” (Harari 2017: 381).

Now it is beyond doubt that the sort of view of humans Harari depicts can have very real consequences. In China, we are currently seeing how an authoritarian regime is establishing a digital surveillance apparatus by means of artificial intelligence. A “social credit system” records and evaluates the consumption and relationship preferences of citizens, their political and social behavior, their creditworthiness and conformity, right down to their criminal record. Facial recognition software, which evaluates public video surveillance, can easily be linked to the system. This is where something like Skinner’s social technology is now being realized and digital dystopias are taking shape.

Nevertheless, defending the human being, his freedom and dignity, must not be limited to painting a gloomy picture of the future. Rather, it must be about criticizing the assumptions behind a scientistic view of humans, which authors like Harari uncritically adopt. These assumptions include in particular the following:

◆ Naturalism: from the point of view of reductionist naturalism, there are no phenomena that elude a complete scientific explanation. In particular, subjectivity, mind, and consciousness can be traced back to physical or

4 Algorithms can be described in simplified terms as defined chains of events with which a system reacts to an input, for example according to the rule: “if a, then b”—“if not a, then c.” Algorithms form the basic structure of the programs which computers run.

physiological processes, i.e., they can be regarded as products of determined neuronal processes. They have no independent effectiveness in the world.

◆ Elimination of the living: the biosciences regard organisms in principle as biological machines controlled by genetic programs. Selfhood, experience or subjectivity no longer appear in this paradigm. The fact that a cat hunts a mouse can then be explained as the effect of biochemical or evolutionary mechanisms—taking its hunger or hunting instinct as a basis is now considered a naive anthropomorphism.

◆ Functionalism: phenomena of consciousness are attributed to processes of neuronal information processing, which transform an input into a suitable output according to algorithmic rules. In principle, these digital processes can run on any carrier (“hardware”), and they can even be simulated by artificial systems. Because it is not the subjective experience but only the function, i.e., data processing and the corresponding output, that constitutes the mind. If these interlinked assumptions were correct, then humans would be far better understood in terms of neuronal processes, genetic algorithms, and digitized behavioral patterns, in short, as the sum of their data, than through hermeneutical understanding, self-reflection, and self-awareness. The “know thyself” of the Delphic oracle would be outdated—the Google algorithms would know us better. The modern chorus of materialistic neuro-philosophy proclaims that our subjective experience is nothing more than the colorful “user interface of a neuro-computer and thus a user illusion” (Slaby 2011)—only the neuronal computational processes in the background are real. From this point of view, subjectivity, self-awareness, and self-determination become epiphenomena which, in everyday life we may still believe in, but which to regard as reality only testifies to naivety and nostalgia.

A defense of the humanistic view of humans, as undertaken in this volume, would be ill-advised if it were limited to proving that consciousness and subjectivity are irreducible. Such a defense would only follow pre-determined dualistic paths—here mind, there body, here qualitative inwardness, there measurable objective facts. In view of the progress of neurobiology, but also in view of increasing digitalization and virtualization, such a defense of a “citadel of the subject”5 could soon prove ineffective—especially if subjectivity and its expressions become simulated more and more convincingly. It is not inconceivable that the simulation of human by artificial intelligence and the simulation of physical presence by robots or virtual avatars could increasingly take the place of human reality. When, for example, do we begin to ascribe something like

5 On this, see Fuchs 2018: xvi–xx.

consciousness to Alexa or Siri on the basis that they express their feelings so convincingly and understand our own feelings so well?

This brings me to the subtitle of the volume, “Embodied Anthropology.” According to my thesis, the actual alternative to a naturalistic-reductive image of the human being consists in attention to the embodiment and aliveness6 that are constitutive of the person. No abstract inwardness, disembodied consciousness or pure spirit are the guiding ideas of a humanistic view of the person, but the person’s concrete physical existence. Only when it can be shown that the person is present in his body itself, that the person feels, perceives, expresses, and acts with his whole body, do we escape confinement in a hidden inner space of consciousness, an inaccessible citadel from which only signals penetrate to the outside world, signals which can no longer be distinguished from the those of an artificial intelligence. And, only when persons have an embodied freedom, i.e., determine themselves as organisms in decisions and actions, does subjectivity become more than an epiphenomenon, i.e., really effective in the world.

Only as embodied, physical beings are we real for each other too. There is no communication or empathy between brains, even if neuroscientists like to claim that.7 We only learn empathy through physical contact with other persons, through “intercorporeality,” as Merleau-Ponty called it. And we understand others primarily not through a “theory of mind,” as current developmental psychology assumes, but already intuitively through the other’s bodily expressions, gestures, and behavior. Only a few weeks after birth, babies recognize the emotional expressions of the mother or father, namely by understanding and feeling these expressions’ melody, rhythm, and dynamics in their own bodies. Theories about the inner life of others only need to be formed by autistic people who have not developed this social intuition—so to say, the musical sense for the resonances of intercorporeality—from birth onwards.8

One might object that we are increasingly moving and communicating in virtual spaces, where our embodiment is becoming more and more obsolete. Recently, the Covid-19 pandemic has furthered the disembodiment of our social life and seems to be triggering a new digitalization push. In the face of global digital networking, human corporeality can increasingly appear as an atavism, from which transhumanists would like to free us through mind uploading 9

6 The rather unusual term “aliveness” is used in the following to describe the condition of being alive or a living organism; “vitality” has more the connotation of vigor or joy of life.

7 See, for example, De Vignemont and Singer (2006); or Hein and Singer (2008).

8 On this, see Fuchs and De Jaegher (2009); and Fuchs (2015).

9 See Chapter 2 “Beyond the Human?” in this volume.

However, apart from the fact that the sentient body is very much a part of any virtual spaces—as every excitement while watching a movie testifies—every digitally mediated online communication presupposes that, beyond all mediation, we are still dealing with a living human being of flesh and blood.10 In other words, all online communication has as its starting or end point the concrete, physical encounter. Even in a primarily virtual interaction we always anticipate this encounter, at least as a possibility.

What the present defense is based on, then, is less the classical humanism of the spirit than a humanism of the living, embodied spirit. As such, it makes use not only of philosophical (in particular phenomenological) analysis but also of the concepts of embodiment, extended mind, and enactive cognition, which have become increasingly important in recent years.11 The fact that humans are not dualistically divided beings of mind and body but above all a living beings of flesh and blood, and as such simultaneously experiencing and aware of themselves—this insight, already found in Aristotle and which today needs to be revived, will form the guiding thread of the following essays. The concepts mentioned previously not only allow for a critical analysis of current scientific and technological developments but also for their productive integration without falling into a backward-looking cultural pessimism. In this sense, the present defense of the human being can certainly be seen as a “defense forward”—namely toward a new, embodied anthropology. Even an ecological redefinition of our relationship to the earthly environment will only succeed if our corporeality and aliveness—as connectedness or conviviality with our natural environment—is at its center. Only if we inhabit our bodies will we also be able to maintain the earth in a habitable form.

The texts collected here, written in recent years and with a view to such an embodied anthropology, explore, in particular, the following topics:

◆ The progress of artificial intelligence and robotics is increasingly challenging the distinction between simulation and the reality of the human being. They suggest on the one hand a computeromorphic understanding of human intelligence, on the other hand an anthropomorphization of artificial intelligence (AI) systems. In other words: we are seeing ourselves more and more like our machines and vice versa. So, what distinguishes human and artificial intelligence? And does the essence of the human being consist of information?

10 See Chapter 3 “The Virtual Other” in this volume.

11 See, for example, Varela et al. (1991); Thompson (2007); Fingerhut et al. (2013); and Fuchs (2018).

◆ Transhumanism regards the human in its present state of development as basically imperfect. The result of evolution is only a blindly grown and therefore poorly constructed, defective product. Our goal should be to create a “Homo optimus” or to free our mind completely from the biological body. Is there a meaningful concept of the posthuman?

◆ The increasing spread of virtuality and digital media also tends to cancel out the difference between embodiment and simulation. When the “virtual other” takes the place of real encounters it becomes all the more important to analyze the potentials and limits of virtual worlds. What distinguishes real and virtual encounters?

◆ Advances in the neurosciences have been instrumental in making human subjectivity appear as an epiphenomenon of brain processes and in undermining the idea of personal freedom. So, are we just creatures of our neurons? Concepts of embodied subjectivity and embodied freedom are able to correct such reductionist views.

◆ Closely linked to the developments mentioned so far is the widespread thesis of constructivism, according to which our perception is no more than an illusory and deceptive construction of subjective realities. This thesis undermines our primary trust in the shared world and fosters the tendencies toward virtualization. How can perception be rehabilitated as an intersubjective constitution of reality?

◆ In psychiatry, naturalistic concepts have led to a reductionist, “cerebrocentric” view of mental illness, which does not do justice to the patients’ experiences and relationships. Does mental suffering really exhaust itself in brain processes? Such views can be contrasted with an embodied and ecological view of the psyche, which can provide a new foundation for psychiatry as relational medicine

◆ Acceleration and digitalization processes finally lead, in western societies, to a repression of the cyclical, bodily rhythms of human time in favor of the monolinear time of growth and acceleration, with well-known psychological and ecological consequences such as burn-out and climate change. To what extent does embodied, lived time resist its socialization and acceleration? These forms and conflicts of temporality must be analyzed in order to better understand social dynamics and to develop strategies for balancing cyclical and linear time.

The most important themes of the following essays are thus identified. It is to be hoped that they will achieve their goal of contributing to the defense of the human—not least against humanity’s own voluntarism. Because modernity’s endeavor to “transform everything given into something made”—as Gernot

Böhme (2010: 143) aptly puts it—has today reached a point where the constitution and freedom of the human being itself is called into question. And it will not only be a question of theoretical reason but an ethical and ultimately a political question whether in this situation a humanistic view of the human being can be defended and at the same time redefined. For, as Karl Jaspers wrote, the image of the human being that we consider to be true ultimately determines how we deal with ourselves and with others—today, we should add: and with nature. Humanism in the ethical sense therefore means resistance to the rule and constraints of technocratic systems as well as to the self-reification and mechanization of humans. If we conceive of ourselves as objects, be it as algorithms or as neuronally determined apparatuses, then we surrender ourselves to the rule of those who seek to manipulate such apparatuses and to control them socio-technologically. “For the power of Man to make himself what he pleases means [ . . ] the power of some men to make other men what they please” (Lewis 1943/2009: 59). The defense of man is, in this respect, not only a theoretical task but also an ethical duty.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Adrian Wilding for his invaluable help with the translation. During the production process I was happy to collaborate with Jade Dixon and Martin Baum from Oxford University Press and with Madhanraj Tharanendran from Newgen Knowledge Works who provided all necessary support.

References

Böhme, G. 2010. “Das Gegebene und das Gemachte.” In M. Großheim and S. Kluck (eds.) Phänomenologie und Kulturkritik. Über die Grenzen der Quantifizierung. Freiburg: Alber (pp. 140–50).

Bostrom, N. 2005. “In defense of posthuman dignity.” Bioethics 19: 202–14. de Vignemont, F., T. Singer. 2006. “The empathic brain: How, when and why?” Trends in Cognitive Sciences 10: 435–41.

Ettinger, R. C. 1989. Man into Superman. New York: Avon.

Fingerhut, J., R. Hufendiek, M. Wild (ed.). 2013. Philosophie der Verkörperung. Grundlagentexte zu einer aktuellen Debatte. Berlin: Suhrkamp.

Fuchs, T. 2015. “Pathologies of intersubjectivity in autism and schizophrenia.” Journal of Consciousness Studies 22: 191–214.

Fuchs, T. 2018. Ecology of the Brain: The Phenomenology and Biology of the Embodied Mind Oxford: Oxford University Pres.

Fuchs, T., H. De Jaegher. 2009. “Enactive intersubjectivity: Participatory sense-making and mutual incorporation.” Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences 8: 465–86.

Harari, Y. N. 2017. Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow. New York: Harper.

Hein, G., T. Singer. 2008. “I feel how you feel but not always: The empathic brain and its modulation.” Current Opinion in Neurobiology 18: 153–8.

Jaspers, K. 1948. Der philosophische Glaube. Zürich: Artemis.

Lewis, C. S. 2009. The Abolition of Man. New York: Harper (First published 1943).

Schopenhauer, A. 1966. The World as Will and Representation, 2 vols., E. F. J. Payne (trans.) New York: Dover (First published 1859).

Skinner, B. F. 1971. Beyond Freedom and Dignity. New York: Bantam Books.

Slaby, J. 2011. “Perspektiven einer kritischen Philosophie der Neurowissenschaften.” Deutsche Zeitschrift für Philosophie 59: 375–90.

Thompson, E. 2007. Mind in Life. Biology, Phenomenology, and the Sciences of Mind Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Varela, F. J., E. Thompson, E. Rosch. 1991. The Embodied Mind: Cognitive Science and Human Experience. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

a Artificial Intelligence, Transhumanism, Virtuality