H OUSEHOLD G ODS

The Religious Lives of the Adams Family

S ARA G EORGINI

1

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

© Oxford University Press 2019

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Georgini, Sara, author.

Title: Household gods : the religious lives of the Adams family / Sara Georgini. Description: New York, NY : Oxford University Press, [2019] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018027755 (print) | LCCN 2018048436 (ebook) | ISBN 9780190882594 (updf) | ISBN 9780190882600 (epub) | ISBN 9780190882587 (hardback : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Adams, John, 1735–1826—Family. | Adams, John, 1735–1826—Religion. | Adams family. | Massachusetts—Biography. | Presidents—Religious life—United States—History. | Christianity—United States—History. | Massachusetts—Religious life and customs. | United States—Religious life and customs.

Classification: LCC E322.1 (ebook) | LCC E322.1 .G46 2019 (print) | DDC 973.4/4092—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018027755

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

Printed by Sheridan Books, Inc., United States of America

This book is dedicated to Philip and Susan Georgini, wise guides on the journey.

Acknowledgments ix

Introduction 1

1. The Providence of John and Abigail Adams 7

2. John Quincy and Louisa Catherine Adams at Prayer 41

3. Charles Francis Adams on Pilgrimage 82

4. The Cosmopolitan Christianity of Henry Adams 119

5. Higher Than a City upon a Hill 168

Epilogue 197

Appendix: The Adams Family Genealogy 205

Notes 207

Selected Bibliography 265

Index 275

A C knowledgments

“Great necessities call out great virtues,” Abigail Adams wrote to her son John Quincy in early 1780. Across oceans and over years, I am deeply grateful to family, friends, and colleagues for their unwavering support of my research adventure with the Adams clan. Recently I unearthed an early graduate school relic, a computer file composed of a single line: “history of one American family’s religion.” As that project wraps up a decade later, I have many people and communities to thank for its progress. Within the family circle, Philip and Susan Georgini, Jenevra Georgini and Steve Macy, and Dorothy Korchinsky were mainstays of moral strength who provided delicious care packages and indulged my long-distance chats about fresh discoveries. As the proud daughter of a social worker and an art historian, I appreciate their knowledge in ways to look at the religious and aesthetic journeys of an American family. At a key moment in this project’s early stages, my late grandmother refined my analysis with Abigail-like acuity. Enduring my whirlwind monologue on archival treasure, she smiled gently and said, “Yes, but what’s it all about?” To her credit, I have asked that on every project since, remembering that archival work plus synthesis can equal good history.

At Boston University, Jon H. Roberts and Brooke L. Blower reviewed chapter drafts and shepherded me through the intellectual and cultural byways of American history. Their patience, expertise, and good humor eased the challenge of a three-century subject. Jon, especially, served as an invaluable mentor throughout my tenure as a graduate student,

introducing me to new platforms and professional networks that honed my intellectual focus on this project and others. I deeply appreciate his steady support of my choice to explore public history as a full-time career while working through the doctoral process. May you all have advisers who encourage you to pick a project that you are passionate about; tell you to sin boldly; and take the time to scrutinize your drafts with great care (even during Red Sox season). I am very grateful for his guidance, as a single line grew into this story.

Brooke’s rigorous review enhanced my thinking on the connections between religion and culture, pushing me to replace academic jargon with a clear narrative. Her seminar assignments, which blended analysis of historiography and material culture, also led me to reconsider the evidence of how Americans interpreted modernity. Telling a story that begins with the Puritans and ends with the Progressives meant investigating the long shadows of early America. Louis A. Ferleger and Bruce J. Schulman renewed my interest in twentieth-century life, clarifying my understanding of the period’s cultural and intellectual contributions. At Harvard Divinity School, David F. Holland sharpened my approach to showing the theological nuances of providentialism, prophecy, and Protestantism.

I owe a great debt to the Massachusetts Historical Society, which has served as a second home for scholars and a public forum for the past since 1791. To thank all of the wise scholars and colleagues who nurtured my research, I would need to list the entire staff directories from 2006 to present. Adams Papers editors then and now—especially C. James Taylor, Sara Martin, Gregg L. Lint, Margaret A. Hogan, Hobson P. Woodward, and Judith S. Graham—have shared resources, read manuscript drafts, attended talks, and good-naturedly endured my ramblings over much-needed coffee breaks. Catherine Allgor, a scholarly champion of the Adams women as political agents, has been a beacon of support. Peter Drummey, Elaine Heavey, and Katherine H. Griffin pointed me to collections that placed the Adamses’ experience of religion in better context. Conrad Edick Wright asked key questions that I needed to hear along the research journey. Many thanks to the entire Massachusetts Historical Society Library staff, who pulled materials on busy days; to Sabina Beauchard and Laura Wulf for illustrating the Adamses’ story; and to the terrific facilities staff, who always gave me

five more minutes to write, and alerted me to free cookies on the premises. I am grateful to the interns, volunteers, teachers, and researchers we have hosted over the past decade. You make us think, every day, about how we can make the archive more accessible.

The society has preserved the family papers with diligence, but nothing beats seeing how the Adamses really lived, in Quincy and around the world. Marianne Peak, Caroline Keinath, Kelly Cobble, and the Adams National Historical Park team kindly opened doors. Their scholarly understanding of how to connect the family’s letters with their home is exceptional and engaging. Visit! At United First Parish Church in Quincy, Pastor Emeritus Sheldon Bennett aided with records access and helped with the mindset of the colonial clergy. Reverend Rebecca Froom provided me with unique opportunities to share my work. Staffs at the National Archives, Library of Congress, British Library, and Harvard Libraries shared expertise. At the Congregational Library, Margaret Bendroth walked me through a vast sea of material, improving my portrait of a faith in transition.

Scholarly dialogue and conversations in an array of communities have refined this work. I thank James Schmidt, Karin Wulf, Natalie Mears, and Chris Beneke for their ongoing support. I am also indebted to the many members of the American Society of Church History, the Organization of American Historians, the Association for Documentary Editing, and the North American Religion Colloquium at Harvard Divinity School and to my peers at The Junto and the Society for U.S. Intellectual History blogs. I am grateful for the extraordinary generosity of the “BookSquad” crew—Liz Covart, Heather Cox Richardson, Megan Kate Nelson, Kevin M. Levin, and Nina Silber—who improved my prose and fed me enough mint chip ice cream to finish the manuscript. Christine Axen and David Mislin offered cheerful support and expert insights on medieval history and liberal Protestantism, respectively, that crystallized Victorian encounters with both fields of thought. Finally, I thank Nancy Toff of Oxford University Press, an extraordinary editor and friend to scholars at all stages, and also Elizabeth Vaziri, for her patient aid in bringing the story of the Adamses’ faith to life.

Thanks, all, for the great virtue of your support.

Introduction

John Quincy Adams, busy packing up Bibles and letterbooks for his new mission as American minister to Britain, rushed through Napoleon’s Paris on last-minute errands. By May 10, 1815, the forty-seven-year-old diplomat and his wife, Louisa, longed for a fresh start in London and for a happy family reunion with their three sons after nearly six years apart.1 Ducking down a side street, John Quincy paused at the studio of Antoine-André Ravrio, bronze-worker to the newly reinstated emperor.2 There, Adams purchased six small busts of Cicero, Homer, Plato, Virgil, Socrates, and Demosthenes. They traveled to his White House mantel; then to the east study and writing chamber of the family’s ancestral home in Quincy, Massachusetts; and, finally, through the colonial garden where his mother Abigail’s pink-white roses bloomed, to the family’s Stone Library of books and manuscripts in Quincy. The statues passed from him to son Charles, and to grandson Henry. John Quincy and his well-traveled heirs always referred to the set as the “household gods,” republican talismans that they could carry away with them, at a moment’s notice, just as Virgil’s Aeneas carried mementos of tradition on his flight.3 Brooks Adams hurried Jazz Age tourists right up to that mantel; a century on, he believed that the household gods handpicked by John Quincy—always guarding the Adamses’ cache of Bibles and

letterbooks—were the best symbols of the family’s Christian service and civic sacrifice.4

A closer look at the Adams family’s multigenerational archive demonstrates how pivotal Christianity—as the different generations understood it—was in shaping their decisions great and small about the course of the American republic that they served for three centuries. Christianity was the cultural language that Abigail Adams used to interpret her husband John’s political setbacks. Scripture armed their son John Quincy to act as parent, statesman, and antislavery advocate. Unitarianism gave Abigail’s Victorian grandson Charles Francis the “religious confidence,” as he called it, to persevere in political battles on the Civil War home front. By contrast, his son Henry found religion hollow and repellent when he compared it to the purity of modern science. Finally, Christianity was the missing link that explained world economic ruin to Abigail’s great-grandson Brooks, a Gilded Age critic of capitalism and the lay prophet of two world wars. Constant globetrotters who documented their religious travels in words and images that total nearly three hundred thousand manuscript pages in the Adams Family Papers alone, over time the Adamses created a cosmopolitan Christianity that blended discovery and criticism, faith and doubt.

In tackling such a sprawl of chronology and subject, I focus on the Adamses who left behind the greatest archival evidence for religious biography. The story begins with the first Henry Adams’s departure from the religious chaos of late Stuart-era Somerset, England, to the new world of Puritan Massachusetts Bay, and it ends with Brooks Adams’s early twentieth-century critique of that same Christian civilization. This arc covers the Adams family’s experience of English persecution, early Congregationalism and town governance, Enlightenment-era education of men and women, biblical poetry and Christian patriotism, Victorian fascination with the visual religion of churches, the cosmopolitan Christianity of Gilded Age culture, and the use of faith and the “household gods” to assess modernity. I draw this story mainly from the diaries, letters, miscellany books, photographs, and related resources of the Adams Family Papers at the Massachusetts Historical Society and the Adams National Historical Park in Quincy. The comprehensive nature of this archive, which features the public and private papers

of more than ten generations, provides a unique opportunity to offer a new history of how and why Americans experiment with religion in a democracy.

The Adamses emerge as key interpreters and innovators of religious culture within a rapidly changing American republic facing denominational turf wars, anti-Catholic violence, a burgeoning market economy, the Civil War, and shifting gender roles. Over the course of the long nineteenth century, personal and public Christianity changed dramatically, leaving lasting imprints on how families lived, worked, played, and prayed. For most American families, Christianity was the cultural framework that they used to explore notions of a special destiny for the new nation, as promised by an omniscient Providence, and of their share in realizing that prophecy. This multigenerational history of the Adams family’s religion provides a unique window into that evolving project.

Asked for their religious affiliation, many Americans now begin their reply with “Well, I was raised . . . ,” but individual family stories of religious life in American history are curiously rare.5 Yet, as the Adamses knew it for three hundred years, at the center of American life lay the Christian family, constructed as a microcosm of national peace, stability, and godliness.6 By using religious biography to frame one influential family’s conversations on faith and doubt, we can capture changes in family worship over time and thereby illuminate greater structural changes in the development of American religion during a turbulent period of revolution, urbanization, and industrialization. We can personalize the working narrative of religious history in America stretching back to the first stages of settlement, by harvesting the private records of individual religious experience as fresh evidence of large-scale social change. And we can linger over a much larger question: What did it mean for the Adamses of Massachusetts to be “raised” Christian in America?

The American family offers a valuable path to comprehending the nation’s major transformations in religious culture.7 In describing American religious change and identifying major intellectual networks, scholars have looked to main-line denominations, iconic preachers, and voluntary associations. Yet the family remains a surprisingly understudied sphere for the development of faith. American religion

mirrored major changes in family and politics, and vice versa.8 Given the numerous sermons preached to guide family life since the nation’s founding, it is worth investigating how one American family actually received, interpreted, and challenged those instructions.

Family history is a vital primary source for intellectual and cultural historians, since the home is a place where religious ideas are inherited, debated, discarded, reinvented, or renewed.9 Families archive signs of faith and pass along religious memories in a way that even churches and clergy cannot record or control. From the colonial period to the early twentieth century, the home was still the primary site for cultivating the education and devotion of religious sentiment. An interior subject as sacred and sensitive as religion was an open topic in Adams family letters, something that parents and siblings frequently used to signal personal or political growth.

Finally, it is high time to reintroduce some very well-known historical actors through the genre of religious biography.10 For the

Affectionately known in the Adams family as the “household gods,” these small bronze busts have stood watch over a vast cache of private papers in Quincy for more than two centuries. En route between high-profile diplomatic appointments, John Quincy Adams purchased the set of six orators (Cicero, Homer, Plato, Virgil, Socrates, and Demosthenes) in Paris in 1815. Antoine-André Ravrio, 1815; Adams National Historical Park

nineteenth century’s prolific first family, the distinguished Adamses of Massachusetts, the ways they “lived religion” were particularly dynamic and well documented.11 As cosmopolitan men and women operating at the heart of American political and cultural power, the Adamses knew that prevailing notions of Christian citizenship laid out duties for them to fulfill, and they repeatedly sought out God for help. Theology supplied an intellectual framework, but the Adamses were far more interested in the practical application of religion to daily life. What could they do with it? Overall, religion served as a kind of moral shorthand or social technology, informing their intellectual and cultural contributions. At critical moments in American history, when they served at the forefront of social change—colonial settlement, the Revolution, the Civil War, the dawn of modern mass culture—the Adamses turned to religion to make sense of new social norms, to guide diplomacy, and to adapt Christian ethics for civic duty.

Less sure-footed in their understanding of non-Western religion and long fascinated by foreign rites, the Adamses were eager to interact with new faiths. Whether traveling for pleasure or to negotiate treaties, they were sensitive to the view that they represented a Protestant nation. Suddenly shipwrecked in northwestern Spain for Christmas 1779, young John Quincy jotted down his confusion at Catholic observance: “They dress up and go to mass but after that’s over all is. So if they call this religion I wonder what is not it; after Mass, almost all the Shops in town are open’d.” Then the budding diplomat hauled himself up short. “But stop. I must not say any thing against their religion while I am in their country but must change the subject.”12

For three centuries, the Adamses chose Protestant Christianity as their main spiritual path. Later and more liberal descendants also explored Catholicism, atheism, and non-Western religion by visiting foreign religious sites, recording rituals in their diaries, trying out new languages of belief in their letters, and bringing home artifacts of religion. But from John Adams through his grandson Charles Francis, the Adams family creed was conventionally Unitarian. They believed in a guiding Providence. They trusted that human will empowered them to freely accept or reject God’s grace. They turned away from miracles and revelation, preferring biblical criticism and lay inquiry to broaden the mind beyond the passive reception of

dogma. Acknowledging Jesus as a “master workman” and gifted moral teacher, they grew fuzzy about his divinity, opting instead to scrutinize his teachings and doctrines as they related to contemporary culture. In line with their Protestant peers, most Adamses mistrusted the sensory emphasis and hierarchical nature of “Romish” Catholicism, but they revered Judaism as a source of lawmaking and ethics.

The Adamses were Christian, cosmopolitan, curious—and famous for it. In popular memory, stories circulated widely about what they believed (and did not) in terms of church and state. Edith Forbes Perkins, a New Englander transplanted to Iowa in the 1870s, noted that the Adamses even found their way into bedtime Bible tales for her six-year-old son. “Don’t you remember about the people whom I read to you about in the Bible, and who lived in that beautiful garden, and whom God created first of their kind?” Perkins asked. “ ‘Oh! yes,’ he replied, with innocent satire, ‘you mean the Adams family!’ And such, no doubt, is the theology of that remarkable New England tribe.’ ”13 At home and abroad, the Adamses’ religion evolved as the new nation grew. This is their story.

The Providence of John and Abigail Adams

In the early winter of 1823, the elderly former president John Adams came out to honor the family’s dead. Emerging from years of rural semiretirement in Quincy, Massachusetts, Adams proudly marked the completion of his last great family project, to commission and place new granite headstones on his ancestors’ graves in Hancock Cemetery. Many of his forebears were buried there, directly across from the First Parish Congregational Church where John prayed twice each Sunday, just as much of his family had done since the community regathered as an independent church in 1639.1 The largest monument he created was for Henry Adams, the English emigrant who arrived in 1638, fleeing the “Dragon persecution in Devonshire” with his wife “and eight sons.” John Adams drafted the text to carve into the native stone, “placed in this yard, by a great-great grandson, from a veneration of the Piety, humility, simplicity, prudence, patience, temperance, frugality, industry and perseverance, of his Ancestors, in hopes of Recommending an imitation of their virtues to their posterity.”2 Some of the history recorded on the plaque later proved to be a bit hazy—scholars have never found a “Dragon persecution”; Henry Adams came from Somerset, and the eight sons who first emigrated were really seven, plus a daughter—but far more indelible was John’s articulation, etched for the public and posterity, of the Adams family values that he was charged to maintain.3

The monument’s inscription and placement echoed an intellectual ideal that Americans before and after the second president struggled with throughout their lives, in both public and private matters: Christianity as the key to implementing duty and reform. To know how they got that way, it is important to see the first Adamses within their native religious ecosystems, and to understand their guiding ideology of Christian providentialism, the belief that God spoke through historical events and intervened in individual lives to fulfill a predestined plan.4 Like many colonists, the Anglo-American Adamses fought to thrive within the cultural and intellectual boundaries of a “double scope, mans good, and Gods honour,” as the English preacher John White put it.5 Identifying and tracking “providences,” or signs of divine will, filled their days.6 That idea carried the Adamses out of England, and the congregations they founded in America led them through the Revolution and, fitfully, into the early republic. The men and women of John’s generation honed their political arguments for independence by invoking the Congregationalist tradition of claiming liberty and articulating dissent.7 They were less successful, however, in mustering that same providentialist rhetoric to address the needs of the new nation. The ways in which John and Abigail Adams used New England Christianity to navigate the world—then returned to Quincy as cosmopolitan critics of that same faith—derived from the family’s earliest roots in American religion. What kind of faith made the Adamses cross the Atlantic and, later on, take up the argument for liberty?

In family memory, the figure of Henry Adams remained forever in flight. Even within the nineteenth-century family circle, no one agreed on the finer points of the English emigrant’s tale. The two Adams presidents, father and son, sparred over Henry’s origin story. John asserted that Henry came from Bristol in 1640, whereas John Quincy upheld an Adams attachment to Reverend Thomas Hooker’s Braintree contingent from Essex County in 1650.8 Both of the amateur genealogists tried—and failed—to pinpoint the number of Henry’s children (nine) who ended up in New England pews. Paying his respects at the Adams cemetery monument in 1824, the Harvard senior Charles Francis reckoned that he marked “the seventh generation since we have been in the new world. In the old we have no traces.”9 As late as 1853, many Adamses claimed a vague link to the Welsh baronial clan of ap-Adams

in County Devon.10 They filled out intricate genealogy wheels, circling round and round different points of English origin. So murky were Henry’s Puritan roots that his heirs considered hiring a private detective to scour the Anglican parish churches of Bath and Wells for manuscript clues. His Victorian namesake, who labeled the Puritans an admirable but “intolerant” class of newcomers to New England, shrugged off the family’s storied past: “I know nothing about the genealogy, and do not invest in it.”11

One reason for the family’s constant myth-making was that Henry Adams made for a difficult research topic. Like other elusive Puritan progenitors who were remodeled by their elite Unitarian heirs, the first Henry Adams left no clear paper trail explaining his abrupt decision, at age fifty-five, to replant the family in Quincy (then called Braintree).12 Little historical residue of the Puritan progenitor remained, beyond his signature on a few wills, deeds, and church records. It was far easier, as time went on, for Adams family members to paint Henry’s portrait in broad strokes of good Protestant virtue. Exhibiting a vaguely AngloAmerican dissenter’s pedigree helped three generations of Adams statesmen and their wives to blend in at foreign courts. En route to the Paris peace talks with England in 1779, John Adams gently refuted the claim of one Spanish official who hoped that the American minister might be of Catalan descent: “I thought these questions very whimsical and ridiculous, but I determined to keep my Spanish gravity and answered them civilly and candidly that I was born in America, and so was my Father and Grandfather, but my Great Grandfather and Great Great Grandfather came from England, where their Ancestors had lived for any Thing I knew, from the Days of the first Adam.”13

A malt-maker by trade, Henry Adams brewed good beer, read widely, and married well.14 The Puritan-era Henry’s daily experience revolved around the three institutional markers of town life that his American descendant John Adams most prized: the meetinghouse, the militia field, and the schoolroom.15 Growing up in the southeastern portion of Somerset, Henry worshipped at the cramped church in Barton St. David; the population has hovered around five hundred since his time. The fifteenth-century church cemetery, oriented around a weather-beaten statue of St. David collecting alms, held no Adams gravestones, but the family’s Protestant affiliation there was multigenerational, even in

Henry’s day. He attended Sunday service in a sixty-three-by-seventeenfoot chapel with Saxon arches. A set of four church bells pealed out on the holy days of the Anglican calendar or to summon his father, a parish tax gatherer and constable, to muster drills with the local militia. As American descendants claimed, Henry and his Somerset friends were “persons in humble but respectable Stations of Life. Not illiterate or uneducated, nor yet of learned professions.”16 Henry’s signature on his father’s 1604 will and, five years later, on his marriage bond, shows the round, Italian-style penmanship of a well-educated Elizabethan youth. Over time, Henry acquired a core library of “ould books” that he willed to his daughter and sons.17

Between duties as a copyhold (tenant) farmer, Henry evidently found time to read, write, and master the math needed to trade goods in England’s developing market towns. The nearest city was Glastonbury, six miles away. Yet Henry would have understood that his ancient church functioned as the true cultural and economic heart of the region. Frequently, Henry and his fellow tradesmen pooled their profits to hire popular traveling preachers for lectures on Sunday afternoons and market mornings. Adams and his neighbors regularly tithed to raise the ten-pound annual salary needed for a permanent pastor.18 The steady presence of a vicar in Barton St. David linked it to hamlets such as Charlton Mackrell, Keinton Mandeville, Charlton Adam, and Kingweston. It was likely through that church connection that Henry met Edith Rosamund Squire, a blacksmith’s daughter and the granddaughter of William Squire, rector of Charlton Mackrell. When he married Edith in October 1609, Henry acquired a generous share of her family’s glebe (church) lands, which he used to set up a brewing business spread over forty-seven acres.19 Between Sundays, Henry and Edith spent their time farming and following the seasonal tasks of a seventeenth-century rural distillery: harvesting barley or oats to dry on a kill floor for malting, then soaking grains in a wooden mash tub with sugar, adding hops to the liquid in a copper keeler as it boiled, and, finally, transferring the English ale to barrels for sale.20 The Adams family’s fortune—and likely their prayers—varied from harvest to harvest.

At first, Henry’s native landscape was relatively untroubled by waves of religious dissent. Aside from some clerical redistricting, the Protestant

Reformation took root easily in Somerset. Henry’s village followed the standard liturgy and devotional practice of the Church of England.21 His evolution into Puritan émigré, therefore, largely happened due to the storm of episcopal reforms that swept through English religious life in the 1630s. In 1633, the Church disciplinarian and radical reformer William Laud was named archbishop of Canterbury. Within months, the look and feel of Anglican religion changed dramatically. The antiCalvinist Laud’s overarching vision of the Church relied on a more dominant clergy and a weaker laity.22 He centered power in the bishops. He required churchwardens to submit annual conduct reports on the behavior of parishioners like Edith and Henry.

Tightening his surveillance one notch more, Laud mandated that churchwardens, ministers, and schoolmasters must report on each other. Laud’s dreaded “interrogatories” meant that Henry could be accosted at any time with an impromptu quiz: Did he remember to bow at Jesus’s name, and to kneel when receiving the sacrament of Holy Communion? Did a mother of nine like Edith Adams don a modest veil each time she returned to the Church after childbirth?23 To the sizable number of clergy and laity who flouted his crusade for conformity, the archbishop meted out excommunication, imprisonment, and deprivation of land. For Henry and Edith, a new symbol of religion took shape on Somerset roads: the white-robed penitent newly released from thirty days of jail, bearing a white wand and heading toward Barton St. David to pay a hefty fine.24

Laud’s economic reforms—standardizing tithe rates in London and improving the professional salaries of rural preachers—reshaped how the Somerset laity lived their religion.25 Adams family profits, for example, changed after Laud reinstituted church support for Sunday sports and ale feasts. Despite the extra income, the marketplace of religious ideas for the Adamses contracted, once Laud terminated the townsmen’s privilege to select and employ itinerant pulpit talent.

Acting on Laud’s orders, ministers and churchwardens could rifle the contents of Henry’s private library whenever they chose, reporting him for punishment if they deemed his reading material immoral. Laud’s next move—to transform the Reformation-era “communion tables” into fenced, railed altars suitable for genuflection—met with widespread resistance.

To Henry’s generation, re-enshrining “God’s residence on earth” was not only expensive but also a treacherous omen that Protestants now favored the same idolatrous adoration as did the Catholic Church. In Somerset, they balked at moving the altar. Henry’s Puritan peers struck back with a few reforms of their own, banning post-church revels and ale feasts. Laud retaliated with royal force. Though he lacked firm reasoning for initiating such severe reforms, the archbishop denounced Henry Adams’s dissenting neighbors as unchristian Englishmen. In Laud’s view, the men and women who grew bold in turning against the Church’s laws might revolt next against their monarch. The Adams family was caught in Laud’s tide.

Given Henry’s need to sell ale and his background as a longtime Anglican, it is hard to know how “Puritan” he really was. Many parishioners encountered Puritanism through their existing webs of kinship. Rather than functioning as a monolithic structure, Puritanism was able to spread largely because worshippers could seize on different

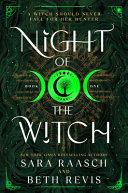

Before crossing over to America, the English Adamses worshipped at the ancient church of Barton St. David in rural Somerset. Photography by Geoff Pick / CC BY-SA 2.0

messages and themes.26 Family history reveals that Henry mixed easily with Puritan clergy and their ideas, especially those of the Reverend John White, an influential advocate of American colonization. The Adams children’s schoolmaster and uncle was Aquila Purchase, a prominent parishioner at White’s Holy Trinity Church in neighboring Dorset.27 Henry and Edith likely attended a few services there; certainly, they heard White’s emigration sermons repeated and debated at home. White, a moderate Puritan and the “patriarch” of the Dorchester Company’s efforts to land colonists at Gloucester, Massachusetts, dabbled in joint-stock ventures. In 1629 he helped to obtain the £3,000 capital from London merchants that funded the Massachusetts Bay Colony’s royal charter.28

He never left England, but White’s zeal led the Adamses to join the estimated twenty-one thousand colonists who made the Great Migration to America between 1629 and 1640.29 Fueling entire families with the godly goals that constituted Puritanism, White leveraged two themes in his lectures: the power of Providence to induce emigration and the mission of Anglo-American colonization as a way to salvage Western Christianity from the meddling attacks of both Archbishop Laud and a host of insurgent Catholics.30 White’s words—amplifying the idea that God wanted them to go, in order to do good—helped to set the Adamses on course for America.

John White’s widely circulated pamphlet of 1630, The Planter’s Plea, furnished Henry’s peers with a providentialist schematic for rationalizing Protestant emigration to the New World. According to White, English families like the Adamses formed the “pettie Colonies” needed to restore and replant Christianity in the new Jerusalem of New England. The act of settling “new States requireth justice and affection to the common good,” White preached, stressing the power of colonization to refine faith through trial.31 He enumerated the mission’s well-publicized perils (snow, serpents, famine) and acknowledged its related costs. He needled his readers, noting that French and Dutch émigrés had managed to flourish there. Then, White warned that it would be worse for a Christian to stay and root in England’s rotten moral climate, growing nearer to the native sins of “cou[v]etousnesse, fraud, and violence” and, thus, farther from heaven.32 John White’s America held new paths to spiritual and temporal profits, along with a native “heathen” populace