https://ebookmass.com/product/homers-divine-audience-theiliads-reception-on-mount-olympus-tobias-myers/

Instant digital products (PDF, ePub, MOBI) ready for you

Download now and discover formats that fit your needs...

Desire in the Iliad: The Force That Moves the Epic and Its Audience Rachel H. Lesser

https://ebookmass.com/product/desire-in-the-iliad-the-force-thatmoves-the-epic-and-its-audience-rachel-h-lesser/

ebookmass.com

Homer's Iliad and the Problem of Force Charles H. Stocking

https://ebookmass.com/product/homers-iliad-and-the-problem-of-forcecharles-h-stocking/

ebookmass.com

Divine Holiness and Divine Action Mark C. Murphy

https://ebookmass.com/product/divine-holiness-and-divine-action-markc-murphy/

ebookmass.com

Inclusion in Action 6th Edition Iva Strnadová

https://ebookmass.com/product/inclusion-in-action-6th-edition-ivastrnadova/

ebookmass.com

Operations and Supply Chain Management, 17e 17th

International Student Edition Edition F. Robert Jacobs

https://ebookmass.com/product/operations-and-supply-chainmanagement-17e-17th-international-student-edition-edition-f-robertjacobs/ ebookmass.com

Coding for Kids 5 Books in 1: Javascript, Python and C++ Guide for Kids and Beginners Bob Mather

https://ebookmass.com/product/coding-for-kids-5-books-in-1-javascriptpython-and-c-guide-for-kids-and-beginners-bob-mather/

ebookmass.com

Thinking 101 Woo-Kyoung Ahn

https://ebookmass.com/product/thinking-101-woo-kyoung-ahn/

ebookmass.com

The Reluctant Carer The Reluctant Carer

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-reluctant-carer-the-reluctant-carer/ ebookmass.com

The Honeymoon Inn Carolyn Brown

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-honeymoon-inn-carolyn-brown/ ebookmass.com

https://ebookmass.com/product/five-first-chances-sarah-jost-3/

ebookmass.com

Homer's Divine Audience: The Iliad's Reception on Mount Olympus

Tobias Myers

Print publication date: 2019

Print ISBN-13: 9780198842354

Published to Oxford Scholarship Online: August 2019

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780198842354.001.0001

Title Pages

Tobias Myers (p.i) Homer’s Divine Audience (p.ii) (p.iii) Homer’s Divine Audience (p.iv) Copyright Page

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP, United Kingdom

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of

Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries

© Tobias Myers 2019

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

First Edition published in 2019

Impression: 1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Data available

Library of Congress Control Number: 2018967556

ISBN 978–0–19–884235–4

Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY

Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. Oxford disclaims any responsibility for the materials contained in any third party website referenced in this work.

Homer's Divine Audience: The Iliad's Reception on Mount Olympus

Tobias Myers

Print publication date: 2019

Print ISBN-13: 9780198842354

Published to Oxford Scholarship Online: August 2019

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780198842354.001.0001

(p.v) Dedication

Tobias Myers for Nina (p.vi)

Homer's Divine Audience: The Iliad's Reception on Mount Olympus

Tobias Myers

Print publication date: 2019

Print ISBN-13: 9780198842354

Published to Oxford Scholarship Online: August 2019

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780198842354.001.0001

(p.vii) Acknowledgements

Tobias Myers

It is a task both pleasurable and daunting to recall the process by which this book came into being, and the many people who contributed to its making. I can still recall the desk where I was sitting, by the window of a 9th-floor apartment on 110th Street in Manhattan, when I first felt the Iliad’s gods begin to work on my perceptions in the way that this book argues they may. My 2011 Columbia University doctoral dissertation was a first attempt to explore the relationship between Homer’s audience and his gods. Subsequent revisions, deletions, and expansions have resulted in a book that retains relatively little of the dissertation’s content, but still reflects the formative ideas and critiques of those who lent their assistance during my time as a graduate student, as well as those who provided support and suggestions over several further stages of development, during my time as a lecturer at Columbia and an assistant professor at Connecticut College.

The faculty and graduate students at Columbia during my time there contributed to a wonderfully conducive environment for research on Homer. Elizabeth Irwin gave generously of her time throughout my dissertation work and beyond. Her brilliant criticism, support, and enthusiasm over a period of many years were invaluable. Katharina Volk not only improved my work with her comments, and suggested the book’s eventual title, but also provided a necessary, steadying perspective at a moment of crisis when I took the prior existence of an article focusing on ‘my’ passages as evidence that I had arrived too late, and might as well give up on the spot. Deborah Steiner, my dissertation adviser, introduced me to the bewitching world of Homeric poetics, and improved my work immeasurably through rounds of exacting readings and extensive comments. Also, my sincere thanks to Jenny Strauss Clay, Helene Foley, Joseph Howley, David Ratzan, Suzanne Saïd, Elizabeth Scharffenberger, Laura Slatkin, and

Nancy Worman for their engagement with my work at this time. Special additional thanks are owed to Jenny Clay for sharing her then unpublished book Homer’s Trojan Theater with me at a crucial moment in my dissertation’s development, for giving (p.viii) me needed confidence by taking my comments on it seriously, and for her support.

Writing a book while teaching at a small liberal arts college presents its own challenges and rewards. Absent the chance meetings with fellow Hellenists on street-corners and in stairwells, or the fierce discussions in lounges after invited talks, and without the push to publish as primary justification for one’s stipend or salary, one feels all the more keenly the value of support and interest from friends outside one’s speciality. I wish to thank friends with whom I discussed the ideas in this book; I think especially of Joshua Babcock, Michael Caramanis, Michael Fish, John Murray, Desiree Sykes, and Andrew Waight. I also wish to thank the many people at Connecticut College who gave friendship and professional advice, especially Ginny Anderson, Simon Feldman, Afshan Jafar, Eileen Kane, Steve Luber, Ross Morin, and Caroleen Sayej. A pre-tenure sabbatical leave granted by Connecticut College in the fall of 2016, and support from the Judith Opatrny fund, provided time for research. The book’s final revisions were completed with the generous support of Sofia Koutsiana and Jackson Kellogg, who gave me the use of their Athens apartment as a daytime writer’s retreat in the winter of 2017–18.

Several classicists offered encouragement, comments, and advice, mostly from afar, whose importance to me would be hard to overstate. Eleanor Dickey gave the right advice at a crucial moment in the quest to get this book published. I thank Helen Lovatt for her encouragement, for sharing her then unpublished book The Epic Gaze, and for her many insightful comments. I am also very grateful to Hayden Pelliccia for his kindness, for the example of his scholarship, and for his deep engagement with my own work by correspondence. Special thanks are owed to Sarah Nooter for her unflagging support and brilliant comments on draft chapters, typically offered within a space of days or hours, at many times over the course of this project’s development. And I thank James Uden warmly for conversations which always left me with a profound sense of the fun, value, and limitless possibilities of scholarship, for his good company throughout many days writing in an Athens library, and most of all for his generosity in reading the entire penultimate draft of my manuscript in just over six days. His comments proved crucial to the final stage of revision.

Valuable feedback on parts of this book was offered by audiences for talks, or conference participants, at Columbia University, the (p.ix) Open University, Cornell University, the University of California at Davis, The George Washington University, Boston College, Connecticut College, and Amherst College. Alexander Loney in particular went the extra mile as a respondent for a paper that would eventually become this book’s Chapter1. Sincere thanks are owed to

Acknowledgements

the readers for Oxford University Press—it is sobering to think what this book would lack, without the benefit of revisions in response to their comments. I also wish to thank the editorial and production teams at Oxford University Press, especially Charlotte Loveridge for her guidance and care with the review process in the final months. Responsibility for any faults that remain in the book belongs to moira, myself, and atē—though not necessarily in that order.

I thank my parents for always encouraging honest exploration, and my siblings Emma, Paul, Peter, and Tamsin, who are each my hero in their own ways. I am very grateful to my children, Nora and Natalia, for their admirable patience while I worked on this project over what has been, after all, their entire lives to date—and for their interesting suggestions and demands about the content of my next book. Most of all, I thank my wife, Nina Papathanasopoulou, for her support, energy, and the countless hours she devoted to revising my work and finding the patterns I could not yet see, sometimes reading new drafts on a daily basis. She also carried our lives at times when I was lost in research, and kept the greater joys of life from ever slipping out of view. I dedicate this book to her, with love and wonder. (p.x)

Homer's Divine Audience: The Iliad's Reception on Mount Olympus

Tobias Myers

Print publication date: 2019

Print ISBN-13: 9780198842354

Published to Oxford Scholarship Online: August 2019

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780198842354.001.0001

(p.xiii) List of Figures

Tobias Myers

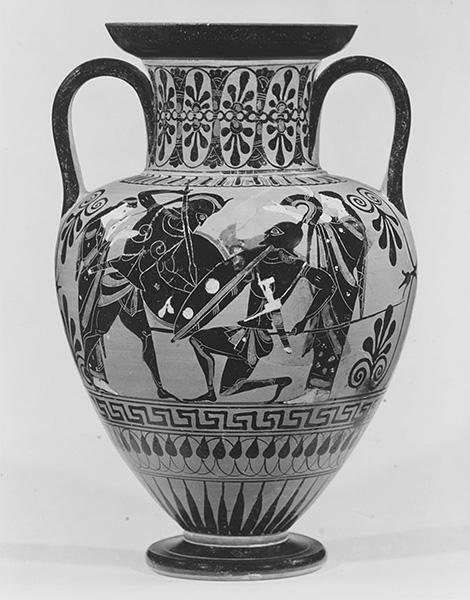

0.1.Sixth-century Attic black-figure amphora depicting Heracles wrestling a lion. Attributed to the Painter of Berlin or the Painter of Tarquinia. The Art Institute of Chicago; Katherine K. Adler Memorial Fund, 1978.114.15

Photo: The Art Institute of Chicago/Art Resource, NY.

1.1.Sixth-century Attic black-figure amphora depicting two female figures, hands upraised, who flank two duelling warriors on whom they also gaze. Attributed to the Medea Group, c. 520 BCE. Side B, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Purchase, Christos G. Bastis Gift, 1961, 61.11.16. www.metmuseum.org.52

(p.xiv)

Homer's Divine Audience: The Iliad's Reception on Mount Olympus

Tobias Myers

Print publication date: 2019

Print ISBN-13: 9780198842354

Published to Oxford Scholarship Online: August 2019

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780198842354.001.0001

Zeus, the Poet, and Vision

Tobias Myers

DOI:10.1093/oso/9780198842354.003.0001

Abstract and Keywords

Chapter 1 argues that the Iliad’s proem anticipates certain key elements of the battlefield spectacle to come: its central action (warfare and the desecration of corpses), and its staging and direction (with Zeus and the poet as joint orchestrators of the battlefield conflict). While the agency of Zeus and that of the poet are highlighted in various ways throughout the text, they overlap specifically in respect to their control of the warfare. Such moments of overlap heighten excitement during performance, as the ‘now’ of performance and the ‘now’ of mythic Troy become momentarily indistinguishable. The chapter concludes by bringing the lessons of its close readings together, to motivate and describe a new approach to the metapoetics of the Iliad’s gods, in place of the prevalent tendency to describe Zeus and the gods as drivers of ‘plot’. Instead, the chapter suggests, divine control should be seen as the flip side of divine viewing, and Zeus recognized as a figure who controls the course of the battle (not the whole plot). One should ask not just how Zeus’ role and the poet’s relate, but also what difference it makes for the Iliad as a performance event. Where textual cues are sufficient, certain scenes of divine viewing can be usefully read as a mise en abyme of the spectacle experience offered by the poet to his listeners.

Keywords: plot,proem,nucleus,enargeia,staging,direction,Zeus,poet,metaperformative

A god can do it. But tell me, how might a man follow through the narrow lyre?

Rainer Marie Rilke1

It is right for me to sing to you as to a god.

Phemius2

The gods’ role as spectators does not become prominent until passages in Book 4 and later. Yet the spectacular quality of those passages depends in no small part on their power to harvest the fruit of ideas introduced much earlier: in particular, the idea that the poem’s essential action is playing out not as a result of happenstance, but as the product of intentional orchestration. Starting with its opening lines, the poem introduces and develops this idea primarily through the presentation of two figures: the poet himself, and Zeus.

(p.28) Sing, goddess, the wrath of the son of Peleus, Achilles –the destructive/accursed [wrath], which set countless sufferings on the Achaeans, and hurled forth to Hades many noble souls of heroes – and them it was making into prey for dogs, and a banquet for birds, and Dios boulē [‘a/the plan/will of Zeus’] was coming to fulfilment –yes, from when first they stood apart, in strife, the son of Atreus, lord of men, and bright/godlike Achilles. Which of the gods, then, brought them in strife to vie?

The son of Leto and Zeus…

By directing the Muse to sing (ἄειδε 1.1), specifying the subject matter (μῆνιν… Ἀχιλῆος 1.1), and selecting a starting point for the narrative (ἐξ οὗ δὴ…and τίς τ᾽ ἄρ σϕωε…1.6–9), the poet introduces himself as a figure of agency. That is, he not only makes these decisions, but enacts the decision-making in propria persona. During these initial moments, the Iliad’s dramatic ‘stage’ is not the plain of Troy, but the setting of the poem’s performance. The dramatic action is the performer’s assumption of the role of aoidos (‘singer’), in view of and for the benefit of his audience, and his presentation of an initial vision of the Iliad:

Achaean suffering, heroes dying, the exposure of corpses, and Zeus’ role in bringing all of this about (1.2–5).

With the sudden statement in line 5 that Zeus’ boulē was being accomplished, the poet invites listeners to conceive of the elements he has just highlighted— violent death, the exposure of corpses—as being not only central to his song, but also crucial, perhaps culminating features of Zeus’ designs. One effect of this move is to set the poet’s vision of the Iliad in a tragic light: the song’s focus, we are told, will be dying and defilement as the realization of an ineluctable divine plan. Another effect is to suggest a parallel between Zeus and the poet. After all, hearing these lines in their dramatic context—the invocation of the Muse—we are also being told that the song’s focus will be dying and defilement as the realization of the poet’s request. The roles of the poet and Zeus are thus suggestively connected, through the results that their activities jointly produce— the epic drama that the audience is about to experience.

The invocation presents a conundrum. As many scholars have noted, bodies are never actually consumed by dogs and birds in the Iliad. Yet the poet presents this situation, which is never to be narrated at all, as though it is foremost in his mind as the poem begins. Zeus, for (p.29) his part, will memorably work to ensure the preservation and proper burial of bodies—not their consumption by birds and dogs.3 I will return to this apparent problem later, to offer a new solution, which emerges in the course of pursuing the chapter’s main objectives.

This chapter explores the programmatic significance of the poem’s early focus on the agency of both Zeus and the poet. It argues that the proem looks ahead to an epic which puts mortality on display—a promise fulfilled at climactic moments in which the audience is led to perceive violent action as the object not only of viewing, but also of deliberate staging and direction. I use ‘staging’ as a shorthand for these interrelated ideas: the act of arranging for an event or set of events to occur (for instance, the day’s battle); the act of arranging for them to occur before the eyes of a viewership; and finally the act of making these staging operations evident to that viewership—that is, the creation of what might be called a staged quality.

‘Direction’ I use to refer to ongoing direct control of a spectacle that has been staged, and is in progress. The word is intended to capture loosely the following set of ideas: Zeus sometimes directs as a general directs—commanding Iris and Apollo, for instance, to deliver his orders to others. He also affects the direction in which the battle turns, toward the Trojans or the Achaeans, as they push back and forth. Like battles, a story may take a particular ‘direction’ (a metaphor particularly apt for story-tellers working in an oral tradition who visualize their story as linear sequence4), and when it comes to the progress of the spectacle at Troy, Zeus, like the poet, sometimes organizes what he sees into narrative form. Finally, we may think of the director of a play—anachronistic as the analogy may

be, it does point to another important quality of Zeus’ direction, namely his interest in creating a powerful dramatic effect. The language of staging and direction is not intended to be prescriptive. Rather, I find it a useful alternative to what has become the standard way of talking about Zeus’ special agency in the Iliad, namely Zeus’ control of the poem’s ‘plot’ (see further below). The key point, which links the various ideas in the foregoing list, is that Zeus’ control helps to define, (p.30) and is itself defined in relation to, the central action—or ‘nucleus’—of a spectacle.5

Both Zeus and the poet stage and direct, in ways that are generally distinct, but sometimes overlap to the point that attempting to distinguish between the two figures seems to run against the grain of the text. Consider, for instance, the opening of Book 11, where Zeus and the poet stage (in all three senses enumerated above) the military spectacle of the third day of fighting.6 First, Zeus sends Eris to the Achaeans’ ships holding a πολέμοιο τέρας (‘portent of warfare’ 11.4). Eris’ shout makes the Achaeans eager for war and fighting (11.12), and makes warfare sweeter for them than going home (11.13). Zeus rouses a wicked confusion, and sends drops wet with blood from the sky οὕνεκ’ ἔμελλε / πολλὰς ἰϕθίμους κεϕαλὰς Ἄϊδι προϊάψειν (‘because he was about to hurl many noble men [lit. “heads”] to Hades’ 11.52–55). This language recalls that of the proem (1.3), while presenting a clearer and more tangible impression of Zeus’ agency: where the proem intimates a vague connection between the fulfilment of Zeus’ boulē (‘plan’ 1.5) and the sending of many noble souls to Hades, in 11.53 Zeus himself is named as the one who will be doing the sending (ἔμελλε…προϊάψειν ‘he was about to hurl’). It is Zeus’ direct control, as much as his observation, that will define this conflict as a spectacle.7

For whose benefit is Zeus’ red rain? It does not seem to be for those who will be fighting. There is no mention of any characters’ reactions to rain tinged with blood, though this would surely be a bizarre and terrifying portent, especially for peoples accustomed to look to celestial and atmospheric phenomena for clues in times of uncertainty.8 The lack of a thambēsan (‘they were amazed’) or chlōron deos (‘green fear’) suggests that the poet is thinking less of an omen for the mortal actors, and more of a signal to his audience that the day’s battle will be extraordinary and terrible.

Further, Zeus’ act smacks of ritual, suggesting something of the nature and import of what Homer’s audience is ‘seeing’ at Troy. (p.31) The evidence of Book 16—where Zeus will again pour down ‘bloody drops’ to the ground, explicitly to ‘honour’ Sarpedon, who is about to die—suggests that the bloody rain in Book 11, too, honours those who are about to perish.9 Indeed, the pouring of blood onto the ground would be familiar to ancient audiences as a very old way of honouring the dead.10 For one accustomed to such rituals, to be witness to this falling blood might be felt as a kind of participation in the act of honouring. Notably, the order of events is here reversed: the blood sent by Zeus

descends to the ground to honour warriors who are not yet dead, at least in the time-frame established by the narration.11 Yet for Homer’s audience, hoi nun (‘men of today’), the race of heroes perished long ago, and so the evocation of death ritual is particularly appropriate. Is this rain, then, a sign sent by Zeus, or by the poet through Zeus? At this point, it would be hard to distinguish; nor, I think, does the text ask us to do so. What is interesting is how the agency of those two figures is highlighted at a point where they largely overlap, thereby presenting the battle as a spectacle intended to command attention, and a complex form of involvement, on the part of the viewer. This is what I mean by ‘staging’; an example of ‘direction’—in the battle for Sarpedon’s corpse in Book 16—is discussed in section1.2below.

This preliminary reading points to a nest of related questions. What is the nature of viewer involvement in the spectacle at Troy? How is the poet’s agency made manifest in the text? How does it relate to that of Zeus? These are complex issues, which this chapter addresses beginning with the proem. Before taking them up, however, it is worth noting another, perhaps more fundamental issue that connects them all: namely, the problem of how to understand the relationship between the world in which the poet sings to his (p.32) audience on the one hand, and the world in which Achilles rages and Hector is buried, on the other.

Three approaches to the problem of how these two worlds relate suggest themselves. Classical narratology would relate them hierarchically, as located on distinct ‘levels’ of narration. The poet’s world—containing himself and his audience—is on an extradiegetic level (that is, outside his own diegesis), and Zeus with all of the other characters are on an intradiegetic level (within the diegesis). This hierarchical conception is fundamental to analysis of the Iliad as narrative. Yet the Iliad does not present itself simply as narrative in the abstract.12 Rather, it is a live event that seeks to involve audiences in the terror and glory of their authentic past.13 The Iliad is art, but it is not fiction. There is a reality that it seeks to attain, however imperfectly, and the poet draws on the divine to make this happen.

A second way to describe the gap between Zeus and poet, or between audience and Troy, is with reference to time-frames. The war is being run by Zeus in the past; whereas the Iliad is being performed by the singer in the present. Indeed, a double temporal perspective is woven into the fabric of our text, which implicitly constructs its audience among ‘the people of the present’ (hoi nun) and, in other passages, among ‘the people of the future’ (essomenoisi). This temporal gap is in some respect bridged, from the audience’s point of view, whenever Homer succeeds in making them feel they are eye-witnesses to past events.

Jenny Strauss Clay, in a study illuminating the remarkable consistency of the spatial layout of ‘Homer’s Trojan Theater’, describes the relationship between worlds in the following way:

To claim that the Homeric poet makes the past present to his audience or that he transports them from the present into the past – although he manages to do both – does not quite do justice to the kaleidoscopic and shifting character of the aoidos’ relation to the heroic world of which he sings. I would prefer to describe that relation less in terms of past and present but instead in spatial terms. The world of the heroes is not only (p. 33) past, it is elsewhere. The Muses can convey it to us not because they were there when the Greeks and Trojans fought but because they are present (πάρεστε) on the battlefield before Troy and are able to transmit what they witness into our field of vision.14

This spatial sense of the shifting relationship between the performance setting and the ‘heroic world’ does indeed emerge from the text, as I will argue, contributing to the Iliad’s presentation of its action as spectacle. In general, I have tried to remain alert to how all three of these basic ways of describing the relationship between worlds—the hierarchical, temporal, and spatial—may interact to shape audience perceptions in a given passage.

This chapter falls into three parts. The first part considers the role of the poet, and then that of Zeus, in the proem and looking forward. It argues that the proem’s interest in narrative content is bound up in its interest in enargeia (the quality of vivid immediacy and presence). The second part moves far ahead in the Iliad to consider an example of the sort of passage for which I see the proem preparing: a passage that draws attention to the union of the poet’s and Zeus’ intentions in a spectacle displaying battle, death, and defilement. A conclusion brings together the lessons of each of the chapter’s close readings, to outline a new way of looking at the metapoetics of the Iliad’s ‘divine apparatus’.

1.1.The Proem’s Promise

1.1.1.The Poet and Audience Involvement

Discussions of the proem’s programmatics often focus on narrative content: plot; theme; character; what the Iliad will be a story ‘about’. But the proem’s anticipation of content, I suggest, is closely bound up with its anticipation of enargeia. The audience is primed not only for the telling of a story, but for a way of conceptualizing the intensity of their experience as they listen to the telling. In supporting this claim, I consider first some stylistic features of the brief, striking narrative of (p.34) lines 2–5 and the speech act of which they form a part (the invocation). I then ask how reminders of the poet’s agency beyond the proem may impact on audience experience of the Iliad’s ongoing performance.

Homeric poetry is famed for making readers as well as listeners into eyewitnesses, ‘riveting our attention to the act in itself and by itself’.15 According to Erich Auerbach’s influential assessment of Homeric style, the story’s action unfolds in a ‘uniformly illuminated’ present that ‘knows no background’. Phenomena are presented ‘in terms perceptible to the senses’, and ‘in a local and temporal present which is absolute’.16 Even scholarship demonstrating shortcomings in Auerbach’s views has often reaffirmed his reading of a vividness that is characteristically Homeric: that is, the smooth, rhythmical succession of phenomena, each of which captivates the mind’s attention in turn.17 As Michael Lynn-George puts it, ‘The achievement of his [Auerbach’s] analysis has been to retrieve another time as a pure present, to make “once long ago” the same as “now”.’18 Whereas Auerbach described Homeric vividness in terms of an unconscious reflex, a ‘need’ to leave nothing obscure,19 subsequent scholarship has shown that on the contrary, enargeia for Homer ‘was a quality to display, reflect on and worry about’.20 The poet wants us to appreciate his poem’s enargeia, and invites us to understand it as deriving from the Muse’s vision, presence, and supreme skill in song.21

I would emphasize that this invitation begins with the proem itself. In a certain respect, lines 2–5 resemble the regular narrative of the (p.35) Iliad. They consist of declarative statements in the past tense, in the same traditional language as the rest of the poem. Yet they present the reverse of what Auerbach claimed to be the essence of the Homeric style. Homeric battles feature vivid anatomical detail, but here fighting and dying are not described—they are evoked obliquely, by reference to their causes (Achilles’ anger, Zeus’ plan) and their effects (souls sent to Hades, bodies made vulnerable to scavengers). ‘Wrath’ is not normally the subject of verbs such as hurling and making. What is missing is precisely that sense of visual immediacy and presence that the Muse’s song is about to supply.22 ‘Homer cannot but concentrate all passion in a momentary scene,’ writes Auerbach. ‘Before and after hardly exist, blank ages that can scarcely be imagined or accounted for.’ Here, however, the gulf between past and present is measured by the contrast between the present imperative ‘sing’ and the past tense verbs of lines 2–5. Instead of the brilliance of a world ‘fully illuminated’, we have the opacity of Dios boulē

In the next lines, with the Muse successfully invoked, we are to understand that the gulf between past and present has been bridged. The poet indicates the approaching prayer-man, Chryses, by using a deictic, as though Chryses were part of a visual field shared by poet and audience: τὸν Χρύσην (‘that man, Chryses’ 1.11—trans. Lynn-George1988: 51). Additional details prolong the shared imagining of Chryses: his fillets, his hands, and his staff of gold (1.13–14). Then, Chryses speaks. Character (or ‘mimetic’) speech breaks down the distinction between the past and present, for it fosters the illusion that the audience is directly hearing voices of long ago.23 Beseeching the assembled Achaeans (λίσσετο

Ἀχαιούς 1.15), Chryses first wishes that ‘you’ may

sack Troy and return safely (1.19–20), then formally requests his daughter’s return, using another deictic to indicate what he brought: τὰ δ’ ἄποινα δέχεσθαι (‘take these things, the ransom’ 1.20).24 As the bard performs this speech, his audience is (p.36) meant to feel themselves present at the assembly, listening along with the Achaeans to Chryses’ plea.25

One might ask at this point just how much the poet’s agency actually figures in the Iliad’s performance following the proem. After all, Homeric performance poses on some level as the enactment of an old, unaltered tradition, in which the poet’s freedom might be perceived as more or less circumscribed.26 Also, in this variation of the opening invocation it is the Muse who has been asked to ‘sing’ (ἄειδε).27 Nevertheless, in continuing to think about the perspective of the implied audience, I would point to the poet’s voice as a potent emblem of continued agency. By calling on the Muse to sing, Homer invites his audience to hear his own living, human voice—when he begins the song proper—as imbued with the numinous power and authenticity they associate with the goddess.28 When Muses sing (ἀείδειν) in their own voices (as at Iliad 1.601–4), they do so for the pleasure of gods. Thus, there is a sense in which the poet of the Iliad is, like Phemius to Odysseus, offering to sing to each of his listeners ‘as to a god’ (ὥς τε θεῷ Od.23.348).29

(p.37) Gregory Nagy similarly connects agency to voice: the poet who must ask the seeing Muses for aid (at Il.2.486) is nevertheless himself ‘the master of kléos’ precisely for the reason that ‘it is actually he who recites it to his audience’.30 Emily Vermeule posits a special delight on the part of poet and audience, a delight derived from their collective, continual appreciation of the poet’s artistry: ‘the goal of a good epic poet…is to kill people with picturesque detail, power and high spirits…and Homer the murderer never bores us.’31 Vermeule is highly attuned to the poem’s artistry (she makes repeated comparisons to ballet), but does not, I think, make sufficient allowance for the poetry’s claim to provide access to a kind of truth that is not available in quotidian life. Vermeule is nevertheless persuasive in positing the audience’s awareness of another kind of truth: that men die precisely when and precisely how the poet’s voice tells us they die; that is, when his words induce us to see it happening.32

On the evidence of the Odyssey, a bard will be judged on the basis of μορϕὴ ἐπεῶν (‘shapeliness of words’), and whether he speaks κατὰ κόσμον / μοῖραν (‘according to the ordering’ or perhaps ‘in the right way’).33 The latter phrases would seem to emphasize the need for authenticity, such as that associated with autopsy: the poet must convince. 34 Meanwhile, it is his words, their shapeliness (μορϕὴ ἐπεῶν), that must make each phenomenon real for the audience. In this sense, the poet’s agency is palpable throughout.

Additional attention is drawn to the poet’s ongoing role by his use of certain identifiable techniques, as a growing body of scholarship shows.35 These techniques include: references to οἱ νῦν (‘the men of (p.38) today’); statements of what ‘would have’ happened next; apostrophes to characters; (re)invocations of the Muse; and the introduction of a ‘hypothetical observer’ or ‘would-be eyewitness’ (e.g., ‘then not even an observant man would have recognized Sarpedon…’). Emphasizing his role as performer entails reminding listeners of their own corresponding role as his audience. Hence, the use of these devices may also be understood as a way of re-emphasizing that sense of separation— first established in the proem—between the ‘now’ of narration and the ‘now’ at Troy.

Yet reminders of the poet’s and audience’s roles should not necessarily be seen as a way of ‘breaking the spell’ that reveals the other world. In many cases, vividness may actually be enhanced. Distance and proximity are not exclusive.36 In fact, the poetry can be at its most captivating when it insists on both at once. Consider this passage from Book 13—one which later tradition will record that Homer chose as his best:37

– 13.339–45

Then battle, that wastes men, bristled with the long spears they held, that slice flesh; and eyes were blinded by the gleam of bronze from their beaming helmets, and new-forged breastplates and shields shining, as they came together. Fierce-hearted indeed would be one who was gladdened then, looking on the struggle, and not grieved.

Helms, breastplates, and shields shine brilliantly. In a move from the abstract to the palpable, the idea behind phthisimbrotos (‘that wastes men’ 13.339), used of the ‘battle’, is recalled and made concrete in the (p.39) next line by tamesikhroas (‘that slice flesh’), used of the ‘spears’.38 One might call this moment the epitome of Auerbach’s ‘illuminated’ present—the foreground reaches out as though to blot out any possibility of a background. Yet pace Auerbach, the illumination is in no way an unconscious reflex.39 I read ὄσσε δ᾽ ἄμερδεν (‘and eyes were blinded’ [literally ‘harmed, damaged’]) as a climactic moment—not in terms of the plot, but in terms of audience involvement. As no one’s eyes are specified (no τῶν δέ introduces ὄσσε ἄμερδεν), the reach of the gleam that blinds is open-ended; it dazzles any eyes it reaches.40 So the poet says; then he makes us see it. This broadly shared visual experience is couched

in a language of harm—amerdo, to ruin or damage. It is as though, in this one respect, even those removed in space and time could be harmed along with the fighters.

Yet in the very words that make this enargeia so compelling, joining past and present, we also find a reminder of continued separation from that brilliant reality. By enumerating the objects sending forth light, the poet compels their visualization: the audience can still see, as can he. The paradox is this: the better we ‘see’—the more successful the poet is in uniting past and present—the more blinded we are. But the blinding will never be total, for we will never be only at Troy.

Reflection on this paradox is evident in the succeeding statement: only someone ‘fierce-hearted’ (θρασυκάρδιος) would be gladdened, not grieved, by looking (13.344–5). The poet is making an evaluative comment, thereby increasing audience awareness of his mediating role (distance). Yet the comment also prompts the audience to think of their relationship to the spectacle in terms of direct visual perception (presence; proximity).41 It does so by posing the question: are you gladdened, or grieved? To entertain this question is to grant, at least provisionally, its premise: that one has, in fact, been seeing the battle.

(p.40) The very self-consciousness of the Iliad’s enargeia, then, can increase its power to captivate. One might say that Homer has indeed achieved a present that is ‘pure’ (Auerbach)—not because it excludes all other time-frames, but because it acknowledges two time-frames while claiming them both as a single present. In this way the separation between worlds that the proem establishes on the one hand, and the enargeia that it anticipates on the other, are working in tandem to generate an effect of greater enthrallment. The proem not only anticipates a story in which Achilles’ anger leads to battlefield death and defilement, but also anticipates an enhanced sense of directly experiencing those past events, through the poet’s ceaseless execution of his song. It remains to be seen how the statement that Zeus’ plan was coming to fulfilment interacts with these other programmatic elements of the proem.

1.1.2. Dios d’eteleieto boulē

The formulaic phrase Dios boulē (‘plan/will of Zeus’),42 here itself used within the larger formula Dios d’eteleieto boulē (‘[the/a] plan/will of Zeus was coming to fulfilment’), serves more than one programmatic purpose. It establishes right away the Iliad’s connection to the larger mythological tradition in which Zeus’ plans figure so prominently.43 Thinking somewhat more locally, one may note that the phrase also anticipates the central importance of Zeus’ decision-making in the Iliad as it proceeds to unfold.44 Of primary concern for the present study, however, is the way that Dios d’eteleieto boulē functions in concluding the series of emotionally charged statements in lines 2–5.45 In this section and the next I will argue that these lines taken (p.41) together serve to anticipate a particular

kind of metaperformative moment that recurs in the Iliad: moments when the poet will pause, while bringing to life a particularly terrible and riveting spectacle, to draw his audience’s attention to the roles of both Zeus and himself in orchestrating all that they are seeing.

By concluding a short narrative (in this case, lines 2–5) with the idea of Zeus’ will coming to pass, Homer appears to be employing a trope of early hexameter poetry. Let us compare passages from two texts roughly contemporary with the Iliad: the Odyssey, and Hesiod’s Theogony. In Odyssey Book 11, Odysseus is telling the Phaeacians of his journeys since Troy. He concludes a brief and partial account of the story of Melampus and the cattle of Iphicles in the following way:

– Od.11.294–7

But when indeed the months and days were filling out their course, with the year coming round again, and the time came –then it was that the might of Iphicles freed him [Melampus], after he [Melampus] told all that was ordained. And the plan of Zeus was coming to fulfilment.

Two related points can be made about Odysseus’ use of Dios d’eteleieto boulē. First, he is marking a moment of narrative transition, within the larger story of his travels: having said as much as he will on the subject of Melampus, he moves on. Second, it seems that Zeus’ plan was coming to fruition through the freeing of Iphicles—the very event which Odysseus, the story-teller in this case, has chosen as an ending for his narration of the tale. Lexical repetition supports such a reading—compare ἐξετελεῦντο, of the time of imprisonment, with ἐτελείετο, of Zeus’ plan. Indeed, the binding of Iphicles has itself been attributed just a few lines earlier to an allotment set by a god (χαλεπὴ δὲ

πέδησε Od.11.292).46

A nearly equivalent formula is used in Hesiod’s Theogony to conclude a story of Jason, Medea, and their child Medeius. Hesiod (the (p.42) voice of the singer) has just told how Jason led Medea away from her homeland βουλῇσι θεῶν αἰειγενετάων (‘through the plans (boulai) of the immortal gods’ Hes.Th.993). He concludes his short narrative with Medeius’ birth (Μήδειον τέκε παῖδα ‘she bore Medeius, her child’ Hes.Th.1001), and upbringing: τὸν

(‘Cheiron, son of Philyris, was raising him in the mountains—and the mind (noos) of great Zeus was coming to fulfilment’ Hes.Th.1002). Though noos appears instead of boulē, exeteleito ensures that we understand noos as a plan with a goal—essentially a synonym

for boulē. Evidently, Zeus’ intention was to see Medeius conceived and raised to manhood. Hesiod, like Odysseus, concludes his mini-narrative with these words and moves on.

In both the Odyssey and Theogony passages, the formula looks backward, marking an ending—not to the larger story, but to the events that have just been recounted. Narrator and god, it turns out, have been aiming for a particular telos. 47 If that of Zeus has not yet been fully achieved—as the imperfect (ex)eteleieto hints—neither perhaps has the speaker come to the end of the song-path on which he first embarked. Probably, he sees always further ahead. Homeric epic, certainly, does not lend itself to finality.

Contemporary criticism loves to find reflexivity in art. It has become common even among classicists (a tribe noted for our resistance to trends in criticism) to discuss Zeus’ control of the poem’s ‘plot’, often explicitly or implicitly assigning a metapoetic significance to his activities. Zeus’ boulē in line 5 is no exception: the phrase ‘appears to define’ the poem’s plot initially,48 has the poem’s plot as a ‘referent’;49 or indeed is ‘the self-proclaimed “plot” of our Iliad’.50 (p.43) Yet caution is in order. There is no word for (literary) plot in Homeric Greek. Instead, we find words richly expressive of the social and cultural contexts in which story-telling is embedded—words such as aoidē (‘song’), oimē (‘songpath’), and klea andrōn (‘glories of / stories about men’).51 Whereas metapoetic readings of the Odyssey begin firmly grounded in the philologist’s demesne— Demodocus and Phemius are aoidoi (‘singers’)—the lexeme boulē does not make so clear an invitation.

Metapoetics will be discussed more fully at the end of this chapter. For now, I would like to suggest that in the case of the Iliad’s proem, the idea of the story’s ‘plot’ is bound up inextricably with the dynamics of the poet’s invocation, his perspective, and his choices. I am not arguing that Archaic Greeks did not conceive of story-lines in the abstract. Indeed, accustomed to hearing traditional tales in many forms and circumstances, they surely must have formed some habits of thinking about story-lines independently of any particular wording, performance, genre, or even medium. Nevertheless, the Iliad proem, by foregrounding the circumstances of performance, pushes audiences away from such abstraction and toward the concrete. Plot does not exist anywhere in particular. Zeus and the story-teller both do. These are figures who appear before the audience on stage, can grip their imagination, and are presented as commanding a direct impact on their experience.52 As the Iliad begins, Zeus is not abstract, so much as distant—like Troy itself. He will not be for long. I suggest therefore that what we tend to read as reflections on the progress of the plot, an abstraction congenial to our critical habits, would be more likely received in live performance dramatically, in terms of intentions realized—those of the poet and of Zeus.

How far do those intentions reach, as portended in the proem? The poet’s narration and Zeus’ plan intersect at line 5. This ‘ending’ looks ahead, unlike the parallel moments in the narratives of Odysseus and Hesiod. Yet it need not look ahead to the poem’s conclusion. No evidence from early hexameter poetry suggests that audiences would expect to be oriented at the beginning of a song by phrases defining or (p.44) referring to the entire plot of the coming narrative.53 Rather, in Hesiod and the Homeric Hymns, as in the Iliad and the Odyssey, audiences are oriented initially by the naming of a theme, an aspect of whose importance is then elaborated. The Odyssey proem’s elaboration of the ‘man’ theme does feature at least one specific plot development from the Odyssey proper—the consumption of the cattle of Helios—but makes no attempt to signal the scope, let alone the outline, of the coming narrative. In the case of the Iliad proem, no specific plot events are mentioned except for the opening quarrel.

One could—joining many critics—detect in this Dios boulē a reference to Zeus’ plan to glorify Achilles by granting Trojan success, which appears later in Book 1. Taking a somewhat longer view of Zeus’ planning, one could also see the phrase referring to the plan of Zeus that aims for Troy’s fall. The destruction of Troy makes a kind of telos toward which the Iliad seems to tend, without ever reaching it.54 A third possible referent, on an even larger scale, is a plan by Zeus to reduce the human population by means of the Trojan War.55 However, critics have been most persuasive in arguing for an ‘open’ or ‘indeterminate’ referent in the Dios boulē of Il.1.5.56 Notably, each of the three referents just listed would situate the poem’s stated theme, mēnis Achilēos, in a different causal relationship with Dios boulē. The phrase thus creates tension, by raising questions of causality, responsibility, and the nature of beginnings.57 Unable to pin (p.45) down the plan, we are left imagining how the words and images we are given—the dying and desecration—may fit with what follows.

The Iliad’s proem poses particularly stiff resistance to being read as an anticipation of the poem’s plot. According to the vision adumbrated here, it is not the ransoming and burial of Hector’s body (in Book 24) that contributes to the fulfilment of Zeus’ plan, but the hurling of souls to Hades and the making of heroes into feasts for animals. Moreover, as James Redfield has observed, the arrangement of aorist to imperfect tenses in the four verbs of lines 2–5 create the troubling impression that the desecration of bodies (in the imperfect), even more than the killing (in the aorist), is the ‘special accomplishment’ of Zeus.58 How is it that the climactic moment of the proem’s narrative seems to be, in the Iliad proper, a non-event—often threatened but never described?

In the face of this obstacle, Redfield nevertheless sees the proem reaching out to embrace the whole Iliad: ‘The poet asks his Muse for the Iliad, and in asking for it must say what it is. The proem thus states in brief compass the whole of which it is the introductory part.’ To reconcile the proem’s content with the content of

the Iliad, Redfield treats content primarily in terms of theme rather than plot: ‘The Iliad, [the proem] tells us, will explore the relations between man, beast, and god; it will be a story of suffering and death, and will go beyond this to tell of the ultimate fate of the dead.’59 This reading, by illuminating thematic connections between poem and proem, does perhaps make the apparent contradictions seem less important. But it does not really explain them. On the subject of Zeus’ agency, Redfield suggests that the proem is ‘partly right’, since ‘gods bring war’, and war brings out human savagery, which leads to the defilement of corpses.60 But finding that the proem is ‘partly right’, by way of such an extended chain of logical connections, is not very satisfying.61

James Morrison has argued that the proem’s carrion-eaters constitute an example of intentional misdirection on the part of the poet. The benefit of this misdirection is found in the cultivation of (p.46) suspense: a ‘first-time’ audience for the Iliad would have to wonder whether Achilles will in fact carry out his threat to see Hector’s body devoured by scavengers, since the narrator has ‘authorized’ such an eventuality from the beginning.62 By this reading, the proem does look ahead to the end of the Iliad after all, since it is only through the ransoming and burial of Hector in Book 24 that the ‘real’ ending finally supersedes that which the proem had seemed to anticipate. I can imagine that Il 1.4–5 might well have the effect Morrison describes on some listeners. Yet I would read the proem as a whole somewhat differently.

It is perfectly possible that an aoidos at the beginning of his performance might be contemplating the song he plans to sing in its entirety.63 However, this is not what the poet of the Iliad gives us. Rather, the impression his words create as he asks the Muse to sing is that of a man gazing out ahead, over the song-path. He sees something essential, and terrible; something that gives him pause. The pause is signalled, even prior to his sudden shift to Zeus, by the imperfect tense of τεῦχε (‘was making’ into prey for dogs…1.4)—a little discussed but significant feature to which we will return. I do not think it is possible to identify a specific moment in the poem on which the poet is pausing (unlike the Odyssey’s explicit reference to the consumption of Helios’ cattle). But I do think that the anticipation he sets up in the proem resonates most powerfully in moments of a certain kind. Let us too journey out far along the song-path, to consider an illustration of the sort of passage that, I suggest, re-echoes with the proem’s promise.

1.2.Realizing the Proem’s Promise: An Illustrative Example from Book 16 Sarpedon lies dead. The fight to capture Troy has become, at least in this area of the front lines, the fight to capture his body. The struggle (p.47) is so ferocious and prolonged that mutilation and dust have robbed the dead man of any visible traces of his individuality (16.638–40). This turn is not without irony, for it is Sarpedon’s particularity—son of Zeus, king of the Lycians, and one of Troy’s greatest defenders—that have made corpse and arms so desirable. Yet at the

centre of the warriors’ frenzy is a bloody shape that might now to all appearances be any body. ‘Not even a discerning man could have recognized him’ (16.638–9), but surely no one in the melee is trying to look. The aggression is relentless, mindless; so much is conveyed by the simile that follows, which likens the men fighting for the corpse to flies swarming over milk in a pail (16.641–4).

At this moment, the poet ‘steps back’ to recontextualize the scene, which he has just been describing so vividly, as the object of Zeus’ gaze:

– 16.644–7

Just so they were moving round the corpse – nor ever did Zeus turn his shining eyes from the fierce fighting –but continually he was looking at them and pondering in his thymos, contemplating the slaughter of Patroclus…

It often happens in the Iliad that an extended description of fighting concludes with a short sentence, introduced by ὥς (just so, thus) and summing up what has been described, before a switch of scene—that is, a move to another area of the battlefield.64 At line 644, however, the sudden incorporation of Zeus who ‘never turned his eyes away’ (16.644–5) rejects, for the moment, that well-established narrative possibility. The poet, as well as Zeus, is refusing to turn away.

The Iliad loves to compel, and comment on, the viewing of a corpse—its beauty, or its violation. Iliadic contests—whether military or funerary—are regularly set in relation to a corpse. The body may be (p.48) the struggle’s product, cause, prize, or honorand.65 Indeed, it may take only a small cue from the poet to ‘flip’ a scene in a listener’s mind, or position the corpse in multiple relations at once, as we will see.

The fixed intensity of Zeus’ gaze defines the nucleus of the spectacle with precision: περὶ νεκρὸν ὁμίλεον (‘they were moving round the corpse’ 16.644); κρατερῆς ὑσμίνης (‘the fierce fighting’ 16.645).66 As the father of the dead man, Zeus has good reason to be interested. The lines carry an emotional charge, as Zeus stares continually, thinking about the killing of his son’s killer (αἰὲν…ἀμϕὶ ϕόνῳ Πατρόκλου μερμηρίζων 16.647). Yet the quality of Zeus’ emotion is difficult to read. Sarpedon’s death was part of a plan of Zeus (as we learned in 15.67). In contrast to Priam, who sees his son Hector killed and defiled in Book 22, Zeus is in total control here, as the passage is composed to emphasize. The opening of Book 13 signalled Zeus’ loss of command with the phrases τρέπεν ὄσσε ϕαεινὼ / νόσϕιν (‘turned his shining eyes far away’) and ἐς Τροίην…οὐ

(‘no longer turned his shining eyes toward Troy at all’). The present passage recalls and reverses that language:

(‘nor did Zeus ever turn away his shining eyes from the fierce struggle, but he was looking at them continually’).

Earlier in Book 16, Zeus had balked at the prospect of his son’s death (16.431–8). Hera then protested, by invoking Sarpedon’s ‘assigned allotment’, predicting the gods’ disapproval, and reminding Zeus that he could ensure that Sarpedon’s body receive funeral rites (16.439–57).67 But it should be noted that Zeus’ hesitance in that earlier scene in no way reduces the importance of his role as director (p.49) of this scene. The opposite is true. Responding to Hera, Zeus uses language that underscores his own, personal agency: ἦ ἤδη ὑπὸ χερσὶ Μενοιτιάδαο δαμάσσω (‘or shall I kill him now, at the hands of the son of Menoetius?’ 16.438). ‘Shall I kill him?’ If Zeus’ heart is divided, his hand and eye are firm.

The poem offers multiple ways of understanding the temporal limits of this spectacle. The battle for Sarpedon’s corpse is well delineated as a coherent episode in its own right, within Book 16.68 Yet that episode also represents one phase of a larger spectacle, itself coherently defined, namely the fighting of the whole day (Books 11–17).69 The day’s fighting, in turn, constitutes a phase in the still greater spectacle of Iliadic warfare—all the battlefield contests that follow Achilles’ quarrel with Agamemnon (Books 3–22), as announced in the proem.70

Moving beyond Zeus, let us now consider the part of the poet. As in the case of the proem, so too the present passage first highlights the poet’s agency and his audience’s involvement, and only then turns suddenly to Zeus. Here are the lines leading up to the moment in which Zeus’ gaze is (re)introduced:

– 16.633–47

And from [the combatants] a din arose – as of tree-cutters, in a mountain glade – and the sound occurs from far away –so their crashing sound arose from wide-pathed earth, [a sound] of bronze and leather and well-made hides, as they kept on striking with swords and two-edged spears. Not even an observant man would any longer have recognized brilliant Sarpedon, since he was covered by arrows and blood and dust from his head to his feet.

And they were moving continually (aiei) round the corpse – as when flies in the stable buzz over buckets overflowing with milk –in spring-time, when milk moistens the pails –just so they were moving round the corpse – nor ever did Zeus turn his shining eyes from the fierce fighting –but continually (aien) he was looking at them and pondering in his thymos, contemplating the slaughter of Patroclus…

The two similes, and the ‘hypothetical observer’ invoked at 16.638, all serve to emphasize the poet’s mediating role, and hence the separation between past and present—even as they contribute to the scene’s vividness. The din must be truly great, we are asked to sense, because it (like the felling of trees) is audible from so far off (ἕκαθεν δέ τε γίγνετ᾽ ἀκουή 16.634). The description of what the ‘observant man’ would see is riveting—the mess of blood and arrows (16.438-40). Yet the optative verb also recalls the audience’s own liminality.71 With the simile of the flies (16.641–4), the poet’s visual focus broadens out again from the corpse itself, to include many small, living bodies—wild motion, against a broader peaceful backdrop. To see fighters as flies requires a capacity for emotional (p.51) distance; or, more precisely, for awareness of the possibility of an emotionally remote perspective on the scene.

At the moment that Zeus is introduced, it becomes possible to understand in retrospect all of the shifts of view, the spatial and emotional distancing, as reflecting the possibilities of divine perspective available to Zeus as well as to the poet and his audience. Zeus, like the poet, can adopt the ‘bird’s-eye’ view From a distance, he can hear the clash of arms (16.634)—as clearly as if it were near (16.635–7). He could see Sarpedon’s body with clarity, recognize him—as the poet can—despite the wounds (16.638–40), even from a great distance. And from as far above as Zeus is perched, the motion round the corpse might well resemble the motion of flies (16.641–3). The repeated use of αἰεί (‘continually’), once for the men fighting and once for Zeus watching them fight (οἳ

16.641, 646), serves to connect the poet’s description of what we and he have been viewing to the viewing activity of Zeus. The effect, ultimately, is to convey a sense that we—

that is, Zeus, poet, and audience—have all been engaged in watching the same action.

The idea of a spectacle that unites viewers qua viewers, even across time and space, finds a parallel in visual art of the Archaic period. Consider Figure1.1, a sixth-century Attic black-figure vase showing two female figures, hands upraised, who flank two duelling warriors on whom they also gaze.72

As Stansbury-O’Donnell notes in his treatment of this vase, the women would not (naturalistically) be found on the battlefield, and ‘we have to consider that their presence here as spectators is conceptual rather than actual’.73 Stansbury-O’Donnell classifies these women as ‘pure spectators’ because they do not belong to the time and space of the nucleus: nevertheless, they look on.74 Temporal separation between spectator and nucleus is thus self-consciously (p.52) acknowledged (by the cues, such as dress, that StansburyO’Donnell identifies), and rendered as spatial separation.

Figure 1.1. Sixth-century Attic blackfigure amphora depicting two female figures, hands upraised, who flank two duelling warriors on whom they also gaze. Attributed to the Medea Group, c. 520 BCE. Side B, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Purchase, Christos G. Bastis Gift, 1961, 61.11.16. www.metmuseum.org.

I suggest that both Homer and the painter of this vase are effectively claiming that the spectacle at the centre of their work can defy temporal boundaries. It is not the case that Homer actually depicts (p. 53) viewers from a different time and place, in the manner of the vase painter. But he does draw on audience awareness of their own viewing experience. The principle is the same: shared vision implies a shared temporal frame. The two cases also have at least some similarity in terms of artistic effect, for both painter and poet show an interest in underlining the trans-temporal importance of the action displayed in the nucleus. ‘The mythological past, like the contemporary battle, is physically removed from the time and place of the viewer, but its impact is real

and immediate as part of the fabric of civic life and belief.’75 These same words could easily be applied to the Iliad’s vision of the Trojan War.

The next lines exploit this moment of textual self-consciousness, to present Zeus in the act of deciding on the direction that the battle will now take:

– 16.646–56

But continually he was looking at them and pondering in his thymos, contemplating the slaughter of Patroclus, whether right away shining Hector should kill him, too – in the fierce fighting – on the spot, over god-like Sarpedon –with bronze, and take the armour from his shoulders, or whether he should keep increasing the steep toil/warfare (ponos), for even more men.

(p.54) And in this way it seemed most profitable to him as he thought, that the noble therapon of Achilles son of Peleus should push the Trojans and bronze-helmed Hector in turn toward the city, and take the lives of many men. And he sent a courage-less spirit into Hector first of all…

Zeus is in effect choosing whether Patroclus’ aristeia will continue or stop right away.76 How is Homer’s audience to react? Are they to sense, on some level, that the poet, through Zeus, is reflecting on his own process of choosing? I would describe the effect in the following way. In this passage, the poet has issued a powerful reminder of the ways in which the spectacle at Troy is being orchestrated. To do so, he has heightened awareness of both his role and that of Zeus. The proem had sharply distinguished the two figures, locating them worlds apart. Now, though, it is not so easy to distinguish fully between them, for the single area in which their manifold roles overlap the most—that is, their relationship to the spectacle they see and control—has now, at this moment in Book 16, become the focus of attention. The passage is reflexive in that it celebrates the power of this song to deliver such an experience.