Acknowledgments

It is a pleasure to acknowledge the many people who have helped and inspired me in writing this book. Several chapters have been significantly improved by the perceptive comments of readers, including but not limited to Karen Bassi, David Blank, Anne Duncan, Emily Gowers, Joshua Katz, Kathryn Morgan, Sheila Murnaghan, Kirk Ormand, Mark Payne, Verity Platt, Charles Stocking, Ralph Rosen, Mario Telò, Victoria Wohl, and Nancy Worman. I reserve special thanks for Jim Porter and Seth Schein, who both revealed themselves to me as readers for the press after the fact, and who have remained in close contact with me since, offering invaluable advice and ideas.

Sheila Murnaghan first gave me the confidence to move forward with this project when I tentatively suggested it to her at a meeting of the (then) APA and she has remained an important guiding force throughout. Kathryn Morgan helped me to piece together its earliest chapters, on falling and running, and thereby to see my way to the whole. Joshua Katz and Verity Platt each stepped in and gave me just the direction I needed during key moments of uncertainty. I wrote the last chapter as the visiting Spinoza fellow at Leiden University. I’ll be forever grateful to Ineke Sluiter not only for her intellectual energy, but also for providing me with a space to work and think among such a warm community of students and colleagues.

Victoria Wohl has gone above and beyond as a reader and interlocutor for this book. I have been humbled by the critical insight she brought to this project, and by her generosity in helping me to make it better. Jim Porter’s ability to step back and assess the whole through a series of thoughtful and penetrating questions has helped me to finesse my argument considerably, and he has been a frequent source of creative input over email. As for Seth Schein, I can’t imagine having written this book without his intellectual guidance. Although all the errors that remain are my own, he has left a lasting impression on me about how

to think and write about Homer, and his generosity as a scholar and a person is unmatched. After retiring at UC Davis, and just as I was beginning this book, he gave me a good part of his Homer library; it has been deeply inspiring to see his name on the inside cover of the books I have consulted for this project.

I also owe a great intellectual debt to my colleagues and students at UCLA. They have provided a community where ideas are celebrated and shared. In particular, David Blank, Francesca Martelli, Kathryn Morgan, Amy Richlin, and Mario Telò (now at UC Berkeley) have all left an impact on this book over the course of several memorable discussions. I have also benefited enormously from conversations in seminars with students, and especially from those who have written dissertations with me on Homer—Charles Stein, Craig Russell, Celsiana Warwick, and Ben Radcliffe—all of whom have changed my thinking and approach to the topic of this book in important and productive ways.

Stefan Vranka, my editor at OUP, has been wonderful to work with; I thank him for his patience, generosity and clear-sighted advice. At UCLA, Chrysanthe Pantages, Silvio Curtis, Zachary Borst, Ana Guay, and Ben Radcliffe provided invaluable research assistance at different points, funded by generous annual grants from the Council on Research at UCLA.

Finally, I am grateful to all of the members of my family. My parents have always encouraged me and have helped me in several ways, large and small, to finish this book. Orlando and Lionel, both much more expert readers of bodies than I am, have made the writing of this book a joyful experience for me, even if it wasn’t always for them. I can’t really thank Lionel adequately for all the time, encouragement, and ideas he has put into the book. It’s an old joke (and true) that I stole the concept for it from him, and he has been the one who has inspired me and talked me through every one of its stages.

List of Abbreviations

DELG P. Chantraine. 1968–1980. Dictionnaire étymologique de la langue grecque: Histoire des mots. Paris: Klincksieck. 2nd ed. with Supplement, 1999.

Denniston J. D. Denniston. 1966. The Greek Particles. 2nd ed. Revised by K. J. Dover. Indianapolis, CA: Hackett.

Dindorf W. Dindorf. (1855) 1962. Scholia graeca in Homeri Odysseam. 2 vols. Amsterdam: Hakkert.

Erbse H. Erbse. 1969. Scholia graeca in Homeri Iliadem. 5 vols. Berlin: de Gruyter.

GH P. Chantraine. 1958–1963. Grammaire homérique. 3rd ed. 2 vols. Paris: Klincksieck.

LfgrE B. Snell et al., eds. 1955–2010. Lexikon des frühgriechischen Epos. Göttingen, Germany: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

LIMC Lexicon Iconographicum Mythologiae Classicae (1981–99). Zürich, München, and Düsseldorf: Artemis and Winkler Verlag.

LSJ Greek-English Lexicon. 1925–1940. 9th ed. Compiled by H. G. Lidell and R. Scott, rev. H. S. Jones. Oxford: Clarendon. Rev. Supplement by P. G. W. Glare, 1996.

Introduction

I thought, as I wiped my eyes on the corner of my apron: Penelope did this too.

Edna St. Vincent Millay, “An Ancient Gesture”

In Edna St. Vincent Millay’s “An Ancient Gesture” (1954), we are invited to contemplate how the gesture of wiping away tears with the corner of a piece of clothing is shared between the bodies of Penelope, Odysseus, and the poet. The poem’s speaker is reminded of the Odyssey after performing a gesture she imagines for Penelope when she, exhausted from long nights unweaving her shroud, wept in longing for her husband. Although this exact gesture is more Millay’s than Homer’s, her poem registers a way of reading and remembering the epic through an association between her own body and Penelope’s. Her protagonist’s simple act, cast here as domestic and ordinary (perhaps it is performed in the kitchen by a woman cutting onions), acquires, through correlation to Homer, a certain resonance.1 As she will go on to write, “This is an ancient gesture, authentic, antique, / In the very best tradition, classic, Greek.” By overlaying her [own] gestures onto those of a fictional character, Millay also suggests some form of a shared experience; a common understanding or empathy that can momentarily occur through the reenactment of a bodily phrase.

But if gestures can be “authentic” they can also be copied and made false. For the poet proposes, in the second and final stanza, that Odysseus stole the eyewiping motif from his wife and turned it into a rhetorical device. In Odysseus’ hands, it is now performed “only as a gesture,” in contrast to “Penelope, who really cried:”

And I thought, as I wiped my eyes on the corner of my apron:

This is an ancient gesture, authentic, antique, In the very best tradition, classic, Greek; Ulysses did this too.

But only as a gesture,—a gesture which implied

To the assembled throng that he was much too moved to speak. He learned it from Penelope . . . Penelope, who really cried.

1. On Millay’s adoption of various markedly feminine personae in her poetry, including that of the wife, see Gilbert 1993; Cucinella 2010: 27–53.

All at once, therefore, the gesture— although it had seemed at first to retain its meaning as it traveled from person to person— is revealed to share only a formal resemblance between the three. It may involve the same mechanics in each case, but the context and emotional impact differ widely as it cycles through Homer’s various characters and readers (even the connection between the poet and Penelope is frayed at the end, as we are left wondering what kind of tears Millay means her speaker-self to have wiped away). Finally, too, the gesture’s initially intrinsic status, as something that was once original to the body of Penelope, is belied by the poem’s marked use of repetition, not only in the formal structure of its rhyming and mirroring within and between the stanzas, 2 but also in its relaying of the gesture from subject to subject (“Penelope did this too;” “Ulysses did this too”). And since Penelope, as we are told, did it “more than once” it becomes clear that the gesture only really becomes a gesture through reperformance, whether by others or oneself. 3

For Millay, then, the simple act of drawing a corner of material up to the face becomes a vehicle not only for engaging with Homeric epic in a personal way but also for thinking through the implications of a genre in which the same gesture can be both deeply meaningful in one case and learned or formulaic in another. The gesture is stored in the body as a kind of muscle memory, one that Millay herself can tap into as a resource for recalling Penelope, but that can also be re-enacted by other characters within the Homeric corpus, leading to an alignment between bodies that is at times unexpected.4

Although my reading of Homer is less personal than Millay’s, in this book I too use specific bodily positions or actions as starting points for interpreting the Iliad and Odyssey. Each chapter begins from a movement phrase (falling, running, leaping, standing, or reaching) and then traces the iteration of that phrase through one or both of the poems. By reading a single or limited number of postures per chapter, I track the sequences and modulations into which a gesture can fall. At times, I follow a thread similar to the one from Millay I have just outlined, such as when I chart the emotional complexities of

2. In addition to the rhyming patterns within the poem (too/do/too; night/tight/light; years/tears; antique/Greek/speak; implied/cried), Millay frequently uses “and” at line-beginning to create a mirroring effect, especially with the opening line of each stanza (e.g., “I thought, as I wiped my eyes on the corner of my apron:” [1]; “And I thought, as I wiped my eyes on the corner of my apron:” [10]), although this symmetrical effect is on occasion deliberately broken (e.g., the second stanza has one fewer line than the first).

3. On the reperformance of gesture, especially gendered gesture, see Butler 1988 (and further in this Introduction).

4. Penelope’s and Odysseus’ contrasting use of gesture in Millay looks toward the long-standing debate over whether gesturing is a “natural” or “artificial” practice, as I discuss later in this Introduction.

Source: Boston Public Library. Wikimedia Commons.

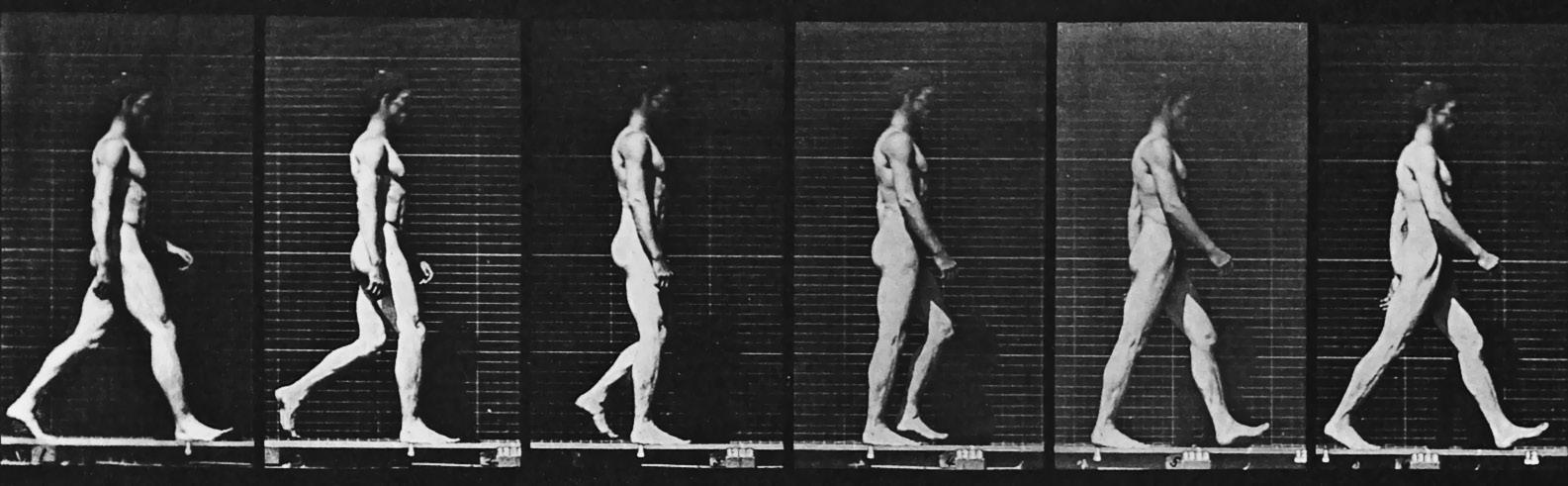

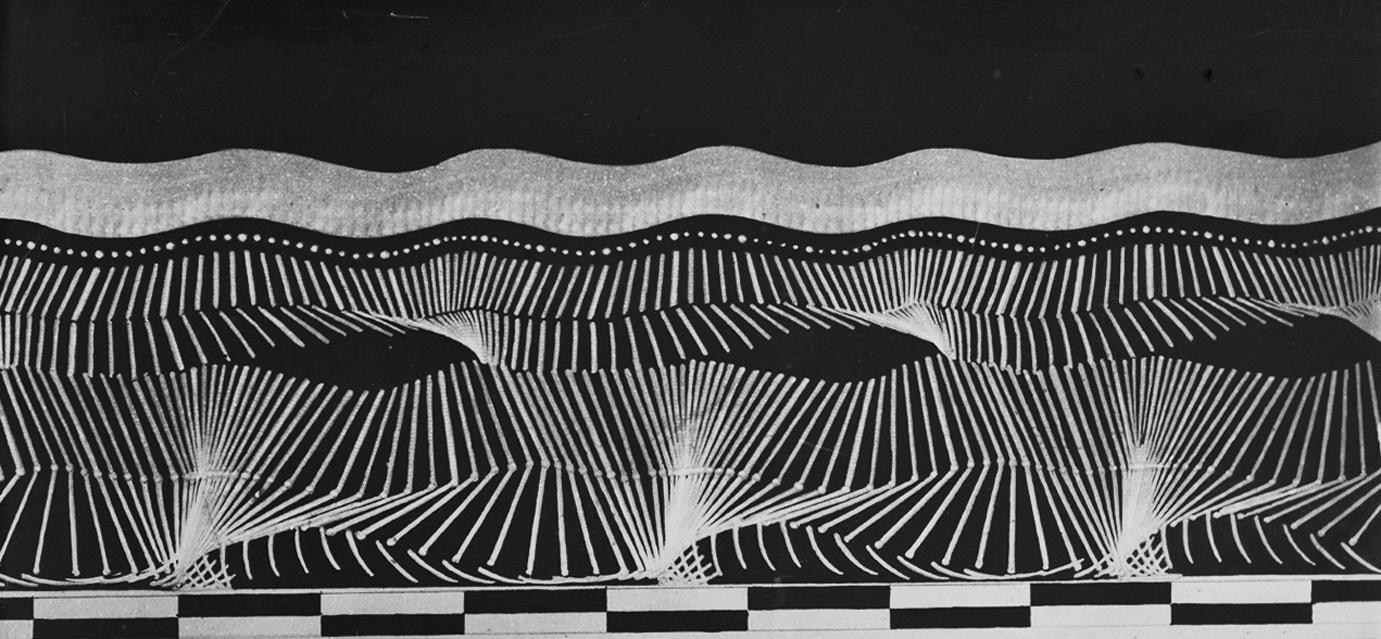

reaching one’s arms out toward another person. But many of the gestures I consider also focus on the whole body, in sequences somewhat akin to Eadweard Muybridge’s famous capturing of movement phrases in a series of stills, as in Figure 1.1.

Like Muybridge, I have been drawn to forms of pedestrian activity whose intricacies are only fully revealed when they are isolated or reframed.5 Indeed, many of these types of activity occur so many times in Homer that they rarely stand out as marked sites for interpretation and analysis. We might instead describe them as providing a background rhythm to the poems, a kinetic structure that is intricately tied to Homer’s engineering of temporality and plot while they in themselves pass largely unnoticed. Action of this kind often blends so imperceptibly with formulaic language (“he came up to him at a run”; “he jumped down with his armor from his chariot to the ground”; “she stood beside the pillar”)6 that their familiarity may condition us to paying barely any attention to them at all. My aim is to challenge that notion by isolating gestures and attempting to capture their kinaesthetic effects within the poems as a whole.

Gesture, though, is a difficult term and one that I want to be careful to categorize both broadly and flexibly. Following the work of scholars such as Vilém Flusser and Carrie Noland, I mean by it whole-body movement phrases rather

5. Many other examples that defamiliarize walking in particular could also be adduced. See, for example, the Judson Church dance collective’s experiments with walking and other pedestrian movements (e.g., Trisha Brown’s 1971 piece “Walking on the Wall”) and my Chapter 5. Agamben’s classic essay “Notes on Gesture” begins with Tourette’s 19th-century medical research into the human walk (Agamben [1992] 2000, and further in this chapter).

6. ἀντίος ἦλθε θέων, three times, Il.; ἐξ

eight times, Il.;

five times, Od. All translations are my own unless otherwise noted; all citations of Homer are taken from the Oxford Classical Text, vols. 1 and 2 (3rd ed., 1920) edited by David B. Munro and T. W. Allen, vols. 3 (2nd ed., 1917) and 4 (2nd ed., 1919) edited by T. W. Allen. On verb-subject formulas, see Parry [1928] 1971: 43; on minimal statements of the kind “strike with the spear” or “his limbs collapsed,” which admit extensive variation, see Hainsworth 1993: 12–13.

Figure 1.1. Eadweard Muybridge, Animal Locomotion. vol. 1, plate 2, Walking (excerpt), 1887.

than, specifically, facial or hand movements used in the service of communication.7 In some contexts, a more suitable term would be schēma, which is used in Classical Greek to refer to the gestures or form of the human body, as well as— in rhetoric—to a figure of speech.8 This meaning is complementary to my own use of “gesture” and helps to expand the term into a figurative and thematic, rather than purely literal, sense.

In Figure 1.2, a “chronophotograph” produced by Muybridge’s contemporary, the physiologist Étienne-Jules Marey, we see a man who, in the process of walking, represents an abstract pattern of movement. The effect is produced by Marey’s choice of where on his subject’s body to place lighted strips, and by the systematic multiple exposure of the same figure on a single plate.9 Whereas Muybridge’s experiments create a freeze-frame effect, capturing a sequence of individual moments within separate grids of time and space, Marey’s photographs result in a fluid running together of the various gradients of a gesture through time. It is worth noting, though, how both images bring to prominence certain parts of the body: the face and hands (our prime denominators of individuality) have disappeared, and instead the limbs alone reveal the contours of human movement.10

7. Flusser [1991] 2014: 1 (“gestures are to be considered movements of the body and, in a broader sense, movements of tools attached to the body”). See also Thomas 1991; Agamben [1992] 2000; Corbeill 2004; Noland 2008 and 2009: 1–17; Väliaho 2010; Olsen 2016 and forthcoming. For gesture limited to communication and thus akin to speech (nonverbal communication), see Kendon 1981 and 2004. Kendon’s reading, which is concerned with semiotics, better relates to Lateiner’s work on the Homeric body than mine. See Lateiner 1992 and 1995 and de Jong 2012 for analysis of gesture as a social and communicative practice in Greek epic. For gesture in other classical genres as well, see Boegehold 1999; the essays collected in Clark et al. 2015; O’Connell 2017: 53–79.

8. See further Schmitt 1990: 34–35 on gestus, motus, kinēsis, habitus, and schema. Greek σχῆμα and Latin schema are used by ancient critics to denote gesture in drama and rhetoric (see also n.28, this Introduction). Quintilian, De oratore 9.1.10–11, says the following of the term figura (“figure”): Nam duobus modis dicitur: uno qualiscumque forma sententiae, sicut in corporibus, quibus, quoquo modo sunt composita, utique habitus et aliquis; altero, quo proprie schema dicitur, in sensu vel sermone aliqua a vulgari et simplici specie cum ratione mutatio (“the word is used in two senses. In one, it means any shape in which a thought is expressed—just as our bodies, in whatever pose they are placed, are inevitably in some sort of attitude. In the second sense, which is the proper meaning of schēma, it means a purposeful deviation in sense or language from the ordinary simple form,” trans. D. A. Russell).

9. On Marey’s photographic method, see Braun 1992: 42–149. In cases such as Figure 1.2, the human figure is dressed all in black, so as to effectively disappear behind the illuminated strips on his limbs.

10. On the body “disappearing” in Marey’s choronophotography, see Michaud 1998: 86, as discussed in Didi-Huberman 2002: 119–20. As the latter puts it, “[i]l faudra donc que les ‘points caractéristiques’— par nature séparés, discrets, discontinus—parviennent à épouser le continuum temporel du mouvement” (emphasis original, 2002: 122), and discussed further in this Introduction.

Étienne-Jules Marey, “Marche de l’Homme: Épure; Graphique obtenu au moyen de la chronophotographie géométrique partielle,” 1882–1886. Source: Collège de France. Archives.

The sweep of the image produced by Marey’s photographic experiments perhaps goes partway to explaining my own emphasis on gesture as “poetics,” as I put it in this book’s title, insofar as I want to suggest that bodies move in formal patterns in Homer and that those movements weave together complex patterns of meaning. The repeated actions and various nuances that make up these gestures have a way of gathering key elements of Homer’s narrative logic into their own sweep or arc. I do not use gesture’s various parts or units, therefore, as an attempt to think of the body as something that exists in pieces,11 but rather as an attempt to explore movement’s connection to the body (and the poem) as a whole. The Oxford English Dictionary defines gesture first as “a manner of carrying the body,”12 and this meaning is important because it shows how deeply gesturing is tied to one’s sense of self (as is also true when gesturing is shared between bodies, I go on to argue). The gesture of falling, for example, takes the whole body down with it, and in a certain way this action is what all gestures do: they remind us that we have a body, and that they are the devices, the vehicles, which “carry” or “bear” (gerere) it.13

11. On “the body in parts,” see the collection by Hillman and Mazio (1997). Snell 1953 famously described the Homeric body as “a mere construct of independent parts variously put together” (6). I discuss the relevance of Snell’s ideas of the Homeric body as an aggregate of parts (1953: 5–8) to my own arguments later in this Introduction.

12. Oxford English Dictionary, s.v. noun, 1a.

13. Agamben [1992] 2000: 57, quoting Varro On the Latin Language 6.8.77 and following the derivation of gesture from gerere. See also Agamben [1991] 1999b and [2005] 2007 and my Chapter 6.

Figure 1.2.

In one case, therefore, gesture might emerge as an effortless, intrinsic expression of the body as a whole, but, in another it might be felt differently—as the burden of oneself, or as something the body has to carry around with it. When Poseidon in Iliad 13 tries to imitate mankind, for example, he cannot quite acquire the ease or “naturalness” of the human walk,14 yet by the last book of the Iliad, gesture operates more as a weight or load to be borne by Achilles and Priam in their grief.15

One of my concerns in this book is to show how the poet structures his narrative in relation to the coordinates and positions of his characters’ bodies. But since gesturing is everywhere in Homer, how and when does it matter and when does it count for the purposes of this book? As I explain further in this Introduction, I count gesture as functioning in a similar way to language and style in the epics, and I focus on those instances of misalignment among the three in which gesture’s importance stands out. When there is a divergence between body and narrative form it can provide unexpected turns in the plot and reveal previously unrecognized temporal and spatial dynamics at work in the poem. For this reason, again, I attach myself to the notion of a “poetics of gesture”; I am each time following a gestural thread, not creating a taxonomy, and that thread takes each chapter in a different direction to make an independent argument. My choice of gesture chapter by chapter can be explained in that, in each case, I trace a movement through repetition that redirects or illuminates the meaning of the poem.

The second way in which the ubiquity of gesture matters to my project is specifically related to epic language and composition, since, as I go on to explain, I understand Homer’s bodies to be formulaic in much the same way as scholars have long understood Homer’s verses to be.16 The ordinariness of actions like walking and standing accords with the ordinariness of formulas repeated numerous times in the poems. The connection between the language of gesture and the language of Homeric formula can thereby help us to think differently about the role of repetition within archaic Greek epic. Although gestures matter to the critical reading of any text,17 it is my contention that they matter in a distinctive way to the Iliad and Odyssey, since they bear a special relationship with, and are indeed in many ways analogous to, the structure and sequence of formulaic speech.

14. Il. 13.70–72. As discussed in my Chapter 2 (51).

15. See my Chapter 6.

16. Since the discoveries of Milman Parry almost a century ago (further references follow).

17. See, e.g., Bolens [2008] 2012.

Formulaic Bodies

Many ritual and social acts in Homer can be analyzed through their adherence to a prescribed set of gestures (supplication, sacrifice, or hosting, for example), as can activities like fighting in battle.18 In this section, I consider gestures as linking phrases that the body may remember and rehearse by a process of second nature, just as formulas are made from a series of words and metrical units that the poet recalls with little apparent effort through habituated training.19 I have already suggested that epic’s gestural units fit together into sequence and combine with other movements in a manner that is analogous to the process of formulaic expression. We can now go a step further and think of gestures as formulas, since the two have remarkably similar properties.20 We are used to looking for phase patterns, formulas, and repeated sequences in Homeric composition, but I propose shifting some of these methodologies over from the formal structure of the poem (its language and meter) to the formal structures (particularly the formulaic gestures) of the bodies within it.

Gesture, then, can be understood to stage a process of articulation through limbs and joints just as epic verse does through verse and meter. Indeed, epic repetition not only comprises words, formulas, and type scenes, but also the oftrepeated postures, gestures, and stances of the epic figure. The Homeric body, like the Homeric line of verse, cannot help recalling and repeating earlier versions of itself, and, just like Homeric language, it has its own movement vocabulary and rhythm, its own way of fitting into the space of the line. Much like a poet who builds on an oral repertoire of stock themes and words, as, through habit, he is called upon to repeat them over and over again, the Homeric hero’s physical repertoire is shored up by a process of somatic repetition, which he then carries with him in the form of habits, acquired gestures, and impulses over the course of the poem.21

How, then, does our understanding of Homeric repetition change when it is plotted not through language or theme but through the dynamics of a moving body? How can our reading of gestures repeated twice, ten, or a hundred times

18. See also Bell [1992] 2009, esp. 69–117, on ritual practice and the body.

19. On cognitive processing in oral composition, see Minchin 2001.

20. There is a danger of falling into a tautological trap here: in a formulaic poem—we could say— everything by its nature will be formulaic. Yet gesture and formula share striking parallels as modes of expression, and I argue that this association is particularly thought-provoking and unique.

21. That is not to say, of course, that there will not be things “only done once” (see Chapter 6) but for the most part, as Fenik 1968 long ago showed us, action in Homeric epic, especially on the battlefield, is deeply repetitive. What I am seeking to capture here, to quote Noland, is the “motivated connection between the kinesthetic experience of performing the gesture . . . and the figurative meaning the gesture conveys” (2009: 60).

across the epics inform our understanding of Homer’s poetic sensibility? How, finally, are the choices of the poet or of characters within the narrative informed by the pull of repetition, its urge to direct the body along particular channels toward the exercising of familiar and well-practiced positions?

Donald Lateiner’s exploration of Homeric gesture as a form of nonverbal communication has shown that epic body language can be read as a text of its own, cueing us to elements of the poem that might otherwise be missed.22 While his research has focused on the social signs that the Homeric body conveys, I am interested in identifying how Homeric movement figures into and complicates the way that the story is told, particularly insofar as it orients itself toward and away from other modes of narrativization at work in the poem. At the same time, in trying to uncover the gestural system at the core of epic language, this book also acknowledges our own physical sensibilities as readers (or listeners) and the sensorimotor modes by which we experience movement. This experience applies to our own kinetic system—the embodied sense of what it feels like to gesture23 but also to our perception of the movement of others, which recent studies suggest we similarly “feel” through kinaesthetic empathy and the processing of so-called mirror neurons in the brain.24

The gestures that a Homeric character—let’s say a warrior on the Iliadic battlefield—performs are thereby dependent on two formulaic systems: both the practice of oral composition in performance and the habits and training of his own (fictional) body as it reacts to the circumstances in which the narrative places him. At the very beginning of Typical Battle Scenes in the Iliad, Bernard Fenik explains that “verse building and action narrative . . represent two aspects of basically the same compositional technique,”25 and this analogy between verse and action applies, both externally and internally, to the poet’s choice of words and to the character’s choice of movement.26 One could argue

22. Lateiner 1992, 1995. See also Boegehold 1999, on the importance of gesture to the ancient Greeks particularly insofar as it supplements (and explains gaps in) speech, as well as Bremmer 1991; De Jong 2012; Clark et al. 2015.

23. Noland 2009.

24. See Craighero 2004; Foster 2008, 2011; Bolens [2008] 2012; Rizzolatti and Sinigaglia 2008; Noland 2009: 14; Shapiro 2011: 109–11; Craighero 2014; Olsen 2017a. Mirror neurons have been shown to fire in imitation when we perceive, read, or hear about an action. On bodily action stimulating the reader’s imagination (enactivism), see Grethlein and Huitink 2017, and the essays, especially the introduction, in Kukkonen and Caracciolo 2014. It would be possible to write this whole book from the perspective of embodied cognition (cf. Clark 2013 on “action-oriented predictive processing,” and Kukkonen 2014) but I am more interested in formal problems concerning the relationship between gesture, style, and narrative.

25. Fenik 1968 (“Summary of Contents”).

26. See Martin 1989: 10 on the overlap between external (poet) and internal (character) speech and his observation that heroes are poetic performers in their own right. I develop this point further in Chapter 4.

that both are essentially the same or that we could not have one without the other, but the doubling effect—that it is not just Homeric language that tends to repeat, but also the Homeric body—is important. The highly stylized nature of epic verse brings to the surface the repetitive underlayer of all gestural practices, what Marcel Mauss refers to as “techniques du corps.”27 Formula and gesture thus stand in tandem, as parallel and mutually reinforcing forms of expression.28 As has long been argued, and as I discuss further here, our gestures represent habits that emerge from social conditioning and repeated practice.29 But if all bodies are formulaic, the Homeric body is especially formulaic, for, like the poet, it knows and recalls its own sequences, its own movement vocabulary and phraseology. And like the Homeric poet, the body “remembers” (what is often referred to as muscle or motor memory) through a process of learned or habitual repetition.

The formula, therefore, once famously defined by Milman Parry as “a group of words which is expressed under the same metrical conditions to express a given essential idea,”30 provides us with a framework through which to consider gesture in Homeric epic as, instead, “a group of [movements] expressed under the same [physical] conditions to express a given essential [event].”31 Indeed, the kinship between formula and gesture as they are discussed in their respective fields is surprisingly strong. They both emerge through a kind of habitual training and both are troubled by claims that they are overly mechanical and too dictated by forces beyond one’s personal control.32 The bard, who relies on a process of training acquired over many years, can be seen to draw on a repertoire of words, phrases, and scenes much as the Homeric character draws on a repertoire of actions or gestures. In both cases, it is acknowledged, there is room for variation and flexibility, but there is also a prevailing sense that the

27. Mauss [1935] 1992, who categorized these techniques much as I (and others) classify gesture.

28. They resemble the later use of the term schēma in oratorical practice as discussed earlier, which refers to both the form or posture of an athlete as well as a figure of speech (Isoc., Ant. 182–83; Hawhee 2004: 35; O’Connell 2017: 53–79). On style and bodily deportment in general, see Worman 2015.

29. On ancient athletic bodily practice and training (ἄσκησις) see Hawhee 2004; Stocking 2016.

30. Parry [1930] 1971: 272.

31. I thank Charles Stocking for helpful discussion on the problem of the term “idea” in Parry’s definition (also explicated in Bakker 2013: 159–60).

32. That these gestures and phrases repeat has traditionally devalued them (for a movement like walking because we execute thousands of steps a day, and for Homeric formulas because of what tends to be seen as their metrically determined or “automatic” placement within the dactylic hexameter). This take on the formula has been well articulated, and challenged, by Bakker. See, e.g. (2013: 10): “The acknowledgment that Homeric language is formulaic, however, does not mean that the utterances of a formula is always done without the memory of other occurrences. Language (whether or not formulaic) is not autonomous, and utterances are never made in isolation, independently of a given context” (see also 157–69).

choices that the Homeric bard or the Homeric figure makes are not really his or her own.

Not only does Albert Lord use the term “habit” frequently in his discussion of oral-formulaic training and technique,33 but he also explains the process of oral composition as a reliance on the “trained reflexes” of the poet.34 Similarly, on the Homeric battlefield—where we see these kinds of reflexes realized in the body of the warrior—action sequences are determined by the physical situation in which a fighter might find himself and there are only a set number of gestures he will perform each time he is confronted with the same situation.35 Both warrior and bard have a repertoire that has become natural over time, but only through a careful process of training and repetition.36 The analogy between the habitual summoning of language and the habitual summoning of gesture is particularly appropriate to the battle narrative of the Iliad, moreover, since this kind of stylized use of the body—whether we want to call it “technique,” “dressage,” or “habitus”—is especially reinforced by military training.37

This is not to suggest, as Michel Foucault did for the eighteenth-century soldier, that Homeric warriors were no more than docile machines, or “automatisms of habit.”38 To do so would bring us back to earlier unproductive arguments defining Homeric characters as puppets without agency and the oral poet as entirely lacking in creativity or spontaneity.39 Yet it is worth bearing in mind that charges of mechanical repetition are brought equally against both gesture and traditional oral style.40 In their reading of gesture, some theorists

33. Lord [1960] 2000: 34, 36, 37, 53, 57, 58, 60, 63, 65, and passim. See also Parry [1928] 1971: 14, 22, 69.

34. Lord [1960] 2000: 58. Despite Lord’s overall push toward a largely mechanical understanding of formula, I have no problem allowing for improvisation and originality within the notion of training, repetition, or reflex. On the resistance to the mechanics of oral-formulaic theory as originally conceived, see Bassett 1938; Kakridis 1949; Nagler 1974; Griffin 1986; Slatkin 1991; Minchin 2001: 33; Elmer 2015. On Homeric repetition and analogy, see Anderson 1957; Lohmann 1970; Austin 1975: 115–29; Edwards 1991: 11–23; Lowenstam 1993: 1–30. For a good discussion of the formula, see Hainsworth 1993: 1–31; Russo 1997. Important work in the history of its analysis, following Parry [1928] 1971 and Lord [1960] 2000, include Hoekstra 1965; Hainsworth 1968; Nagler 1974; Kahane 1994: 5–16; Watkins 1995: 471–504; Stocking 2010; Elmer 2010 and 2015, all with further references.

35. Fenik 1968.

36. See also Ingold 2011: 51–62; Noland 2009.

37. “Technique”: Mauss [1935] 1992; “dressage”: Lefebvre [1992] 2004: 38–45; “habitus”: Mauss [1935] 1992: 458; Bourdieu [1972] 1977: 72–95, [1980] 1990a: 52–79; Crossley 2013; cf. Brecht on social gestus ([1930] 1992: 104).

38. Foucault [1975] 1995: 135 and 135–69. On the Foucauldian body in relation to the ancient and modern subject, see Porter 2005.

39. The scholarship on both topics is extensive. For recent assessments, with bibliographies, see Haubold 2007 on the poet, Purves 2015 on “Homeric man,” and Holmes 2010: 1–83 on the Homeric body.

40. Gestures, like epithets, have been called “iterable and easily detached from the specific contexts of their performance” (Noland 2008: xi–xii).

propose that the body entirely conforms to social regulation and conditioning and that all gesture is therefore unnatural and stylized. Pierre Bourdieu is well known for his argument that physical deportment in general (hexis, habitus) can be understood as a result of the invisible enforcement over time of dominant ideologies,41 while Judith Butler has persuasively maintained that gestures are performed and consolidated according to the cumulative re-enactment of a gendered script.42 Gesturing may be unconscious, but it is still a social act. As Henri Lefebvre has put it ([1992] 2004: 39),

[t]o enter into a society, group or nationality is to accept values (that are taught), to accept a trade by following the right channels, but also to bend oneself (to be bent) to its ways. Which means to say: dressage [breakingin]. . . . One breaks-in another human living being by making them repeat a certain act, a certain gesture or movement.

If we follow these arguments to their extremes, human gesture becomes aligned with the repetitive work of puppets or machines and the notion of an active, creative subject starts to fade away.43 Such arguments are familiar to scholars of Homeric poetry, who have wrestled with precisely the problem of the individual’s agency, both in narrative terms and along the lines of more formal properties such as theme, type, and language.44 The challenge then becomes finding a way to read the Homeric body for both its repetitive and autonomous natures, both its “traditional referentiality” and its originality.45

A similar problem persists in reconciling the deeply repetitive and sometimes “automatic” nature of Homeric style (one third of both epics is made up of repeated phrases) with literary interpretation. Arguments as to how ornamental or unthinkingly reflexive an epithet is, or how problematic or accidental wholesale repetitions of scenes are, especially when they seem to take the plot off track, have led to suggestions that the poet is unsophisticated in the art of literary composition, rapidly plugging in bits and pieces of various scripts without making

41. The idea goes back to Aristotle, where it is cast in a positive light, as the practice of euexia (good bodily disposition). See further Hawhee 2004: 4; Sloterdijk 2009 (2013).

42. See, for various different approaches to and extremes of this position: Bourdieu [1972] 1977, [1980] 1990a; Foucault [1975] 1995: 135–69; Young [1980] 2005; Butler 1988 (“[gender is] an identity instituted through a stylized repetition of acts,” 519, emphasis original), 1997; Agamben [1992] 2000; Lefebvre [1992] 2004: 38–45. See Corbeill 2004 on Bourdieu’s habitus in relation to Roman gesture.

43. Noland 2009.

44. Purves 2015: 76–78, with references. On the question of the hero’s agency beneath the controlling hands of the gods, see esp. Snell 1953; Lesky 1961; Williams [1993] 2008.

45. The phrase “traditional referentiality” is applied by J. M. Foley to Homeric poetics in an effort to privilege the immanent inherent meaning of repeated words and to de-emphasize any situation-specific meaning (1991, 1999). See further Danek 1998: 1–22, 2002; Kelly 2007a.