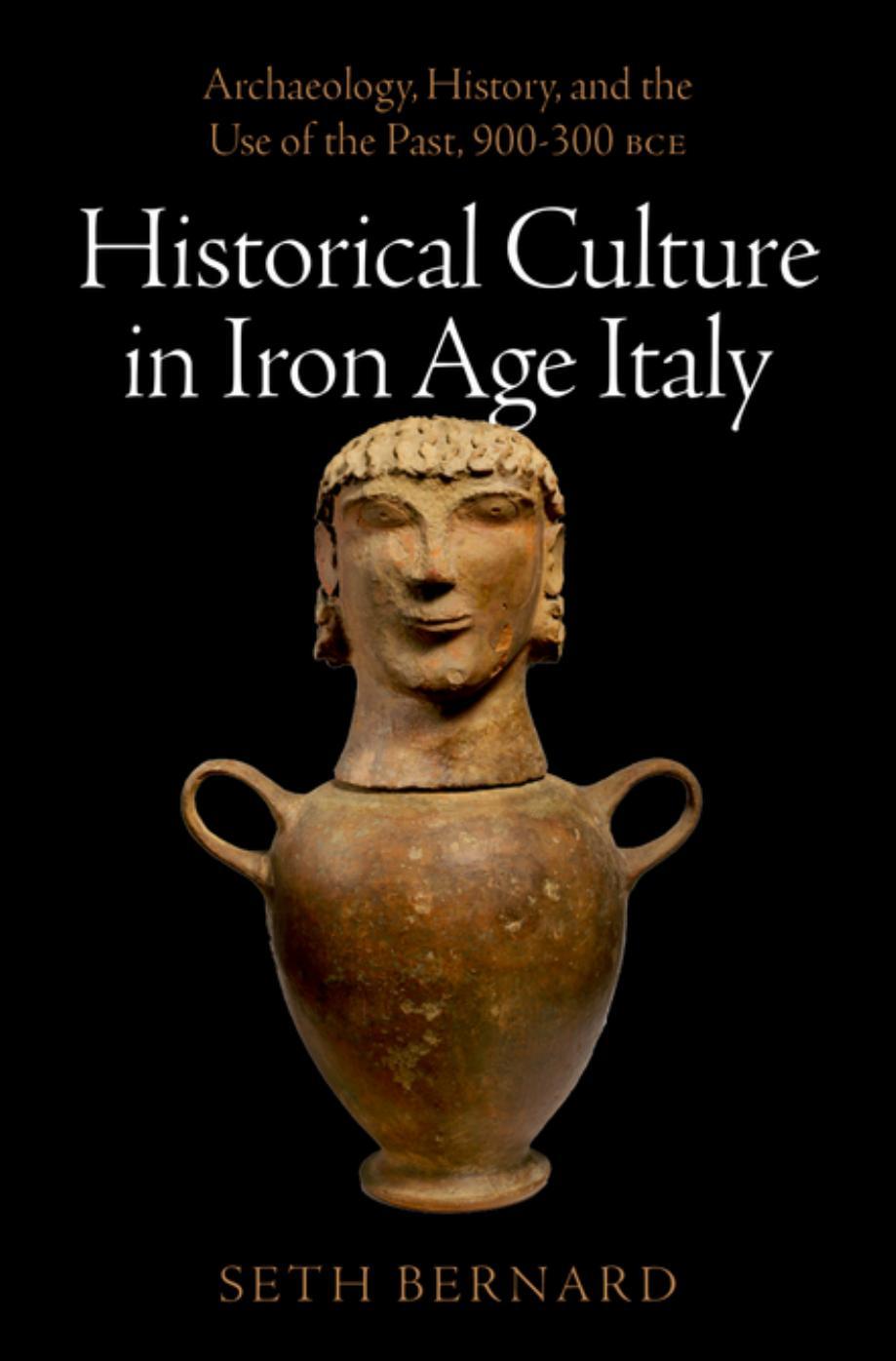

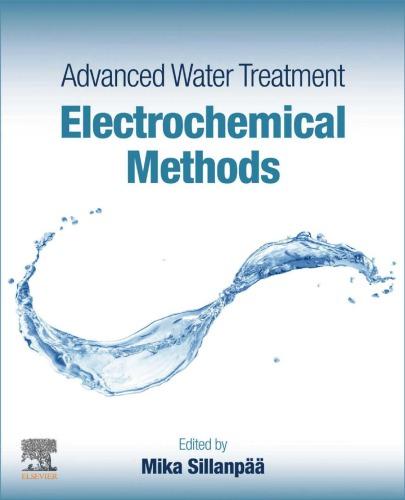

Historical Culture in Iron Age Italy

Archaeology, History, and the Use of the Past,

900–300 BCE

SETH BERNARD

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

© Oxford University Press 2023

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Bernard, Seth (Classicist), author.

Title: Historical culture in Iron Age Italy : archaeology, history, and the use of the past, 900–300 BCE / Seth Bernard.

Description: New York : Oxford University Press, 2023. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2023019456 (print) | LCCN 2023019457 (ebook) | ISBN 9780197647462 (hardback) | ISBN 9780197647486 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: Iron age—Italy. | Excavations (Archaeology)—Italy. | Italy—History—To 476—Historiography.

Classification: LCC GN780.22.I8 B47 2023 (print) | LCC GN780.22.I8 (ebook) | DDC 937—dc23/eng/20230512

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2023019456

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2023019457

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780197647462.001.0001

Printed by Integrated Books International, United States of America

Maps

Map 1. The Italian Peninsula showing ancient regions and cultural areas. Location of Maps 2–4 indicated by boxes. Drawn by author with base GIS and hillshade data from EEA and place locations from Pleiades and Google Earth.

Map 2. Northern Italy and the Po Valley showing location of sites mentioned in the book. Drawn by author with base GIS and hillshade data from EEA and place locations from Pleiades and Google Earth.

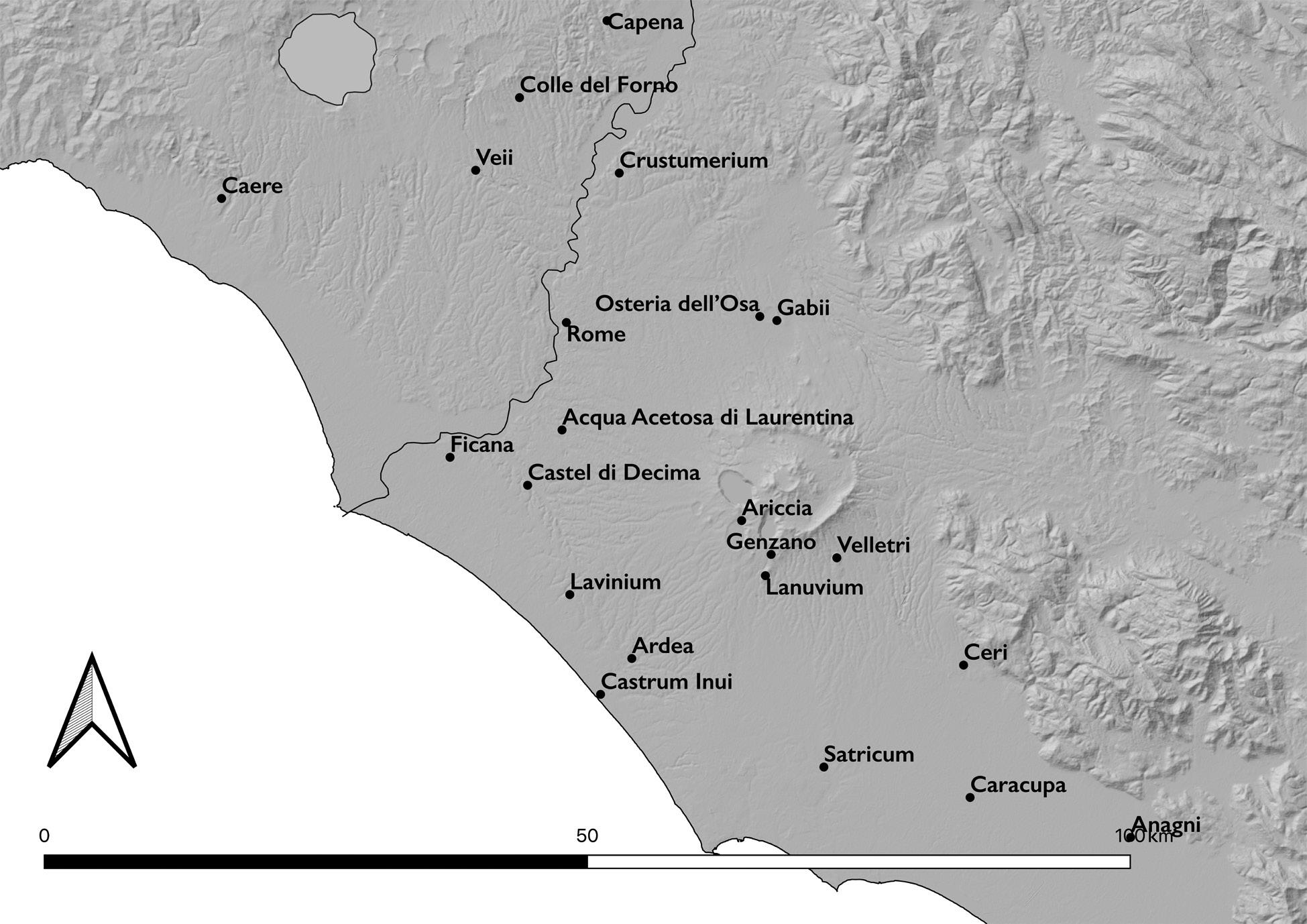

Map 3. Central Italy and the Tiber Valley. Drawn by author with base GIS and hillshade data from EEA and place locations from Pleiades and Google Earth.

Map 4. Southern Italy and Magna Graecia. Drawn by author with base GIS and hillshade data from EEA and place locations from Pleiades and Google Earth.

Illustrations

Figures

1.1. The sarcophagus of Laris Pulenas. Tarquinia, late third century BCE. Image adapted from Vianduval on Wikimedia commons, used with the kind permission of the Parco Archeologico di Cerveteri e Tarquinia.

1.2. Reconstruction of the monument of the Spurinnae family with statues and descriptive texts (elogia). Tarquinia, first century CE. Image by Nicola Terrenato based on an original by Mario Torelli, reproduced with permission of the author and Cambridge University Press.

2.1. Early phases of burial (tenth–eighth centuries BCE) in northwest area of Iron Age necropolis of Osteria dell’Osa, Latium, showing expansion from initial groupings North and South to other clusters. Drawing by author based on data in Bietti Sestieri 1992.

2.2. Cortona, the stepped altar of the Sodo II tumulus, mid sixth century BCE. Photo adapted from Sailko on Wikimedia Commons.

2.3. Tarquinia (?), conically shaped disc of nenfro with human and animal frieze in low relief, possibly a tomb-marker. Image after Milani 1909, tb. 6.

2.4. Vetulonia, the stele of Avele Feluske, 625–600 BCE. Photo from Wikimedia Commons.

2.5. Capestrano, monumental statue of a warrior, possibly from a tomb. Photo from Wikimedia Commons.

2.6. Orvieto, tomb marker in the shape of a helmeted head, identified as Larth Cuperes son of Aaranth by an Etruscan inscription. Photo from Wikimedia Commons.

2.7. Stele with paleosabellic inscription and relief of human face from Penna Sant’Andrea. Photo adapted from Sailko on Wikimedia commons.

2.8. Caere, tumuli in the extensive Banditaccia necropolis. The burial area was laid out in the early seventh century BCE. Photo by author, used with the kind permission of the Parco Archeologico di Cerveteri e Tarquinia.

5

14

40

47

51

52

54

55

56

58

2.9. Architectural evolution of burial in Etruria from ditch grave to monumental tumulus after Prayon 1975: 14. Adapted from Riva 2010: figure 29, reproduced with permission of the Licensor through PLSclear. 59

2.10. Pisa, the cenotaph on via San Jacopo, early seventh century BCE. Photo adapted from Alecobbe on Wikimedia Commons. 62

2.11. One of four mace-head-shaped sceptres of iron and bronze with scene of the lord of horses found in tomb 8 at Spoleto, seventh century BCE. Image © Joachim Weidig. 65

2.12. Ivory writing table with alphabetical inscription in Etruscan from a grave in Marsiliana d’Albegna, ca. 650–625 BCE, image published by concession of the Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Firenze (Direzione regionale Musei della Toscana). 69

2.13. Pithecussae, Rhodian cup with Greek metrical inscription, ca. 740 BCE, found in the burial of a boy about ten years of age. Photo adapted from Marcus Cyron on Wikimedia Commons. 71

2.14. Montescudaio, cinerary urn with figural decoration, early seventh century BCE. Photo adapted from Sailko on Wikimedia commons. 74

2.15. Chiusi, cinerary urn with lid shaped like human head, sixth century BCE, image © Metropolitan Museum of Art object 96.9.50a–b. 76

2.16. The facing statues of seated figures from the vestibule of the tomb of the statues of Ceri. After Tuck 1994, reproduced with permission of the Licensor through PLSclear. 77

2.17. Reconstruction of the interior of the tomb of the five seats from Caere (left) with figure seated on throne (right). After Tuck 1994, reproduced with permission of the Licensor through PLSclear. 79

2.18. Statue B of a male figure from the necropolis of Casa Nocera, Casale Marittimo, early sixth century BCE, image published by concession of the Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Firenze (Direzione regionale Musei della Toscana). 81

2.19. Lunigiana, funerary stele found in 1975 at Cavallino di Taponecco. Image reproduced with permission of the Museo Statue Stele delle Lunigianesi. 82

3.1. Rome, cuttings for an Iron Age hut found beneath later structures on the southwest Palatine by the scalae Caci. Photo © John N. Hopkins. 93

3.2. Satricum, phases of the temple-complex of Mater Matuta, showing the progression from huts to single cella structure to peripteral temple. Photo copyright of the Satricum Project—University of Amsterdam. 95

3.3. Plan of the fifth-century BCE temple at the locality of Colle della Noce, Ardea, in Latium, showing the position of several Iron Age huts below the structure. Drawn by author based on Crescenzi and Tortorici 1984. 96

3.4. Plan of the Etruscan city of Marzabotto. Image © Elisabetta Govi. 105

3.5. Sant’Ilario d’Enza, curved bronze finial of an augural staff or lituus. Reproduced with the permission of the Musei Civici di Reggio Emilia. 109

3.6. Populonia, modern reconstruction of the “House of the King” on acropolis, ninth century BCE. Photo © author.

3.7. Populonia, deposit of drinking cups made in the early seventh century BCE during the destruction of the Casa del Re. Photo © Gilda Bartoloni.

3.8. Gabii, the so-called regia, a tripartite building ritually destroyed and buried ca. 500 BCE. Photo © Marco Fabbri.

4.1. Poseidonia/Paestum, the heroon and its precinct, ca. 500 BCE. Photo from Wikimedia Commons, image © Parco Archeologico di Paestum e Velia / Ministero della Cultura.

4.2. Veii, reconstruction of the funerary chapel on Piazza D’Armi showing small and larger structures built around an early ninth-century BCE burial. Drawing © Gilda Bartoloni.

4.3. Veii, reconstruction of acroterial terracotta sculpture from the roof of the funerary chapel of Piazza d’Armi showing a life-sized depiction of a standing male figure and a dog. Drawing © Gilda Bartoloni.

4.4. Tarquinia, view of the Ara della Regina. Photo © John N. Hopkins, reproduced courtesy of the Soprintendenza archeologia belle arti e paesaggio per la provincia di Viterbo e per l’Etruria Meridionale.

4.5. Tarquinia, view from above the foundations of Altar Alpha beside the Ara della Regina. The stone chest or sarcophagus is visible beneath the lowest course. Photo © Giovanna Bagnasco Gianni, reproduced courtesy of the Soprintendenza archeologia belle arti e paesaggio per la provincia di Viterbo e per l’Etruria Meridionale.

4.6. Schematic section of the shrine atop a seventh-century BCE burial on the southwestern Palatine Hill, Rome. Drawing by author, adapted from Smith 1996.

4.7. Remains of the Iron Age burial chamber (foreground) and foundations of Middle Republican pronaos of the so-called heroon of Aeneas outside the walls of Lavinium, Latium. Photo © author.

4.8. The two altars in the sanctuary at Castrum Inui (Ardea), Latium, viewed from the cella of Temple B looking west toward Temple A. Observe the oblique orientation, possibly corresponding to the description of Dionysius of Halicarnassus. Photo © author.

5.1. Pyrgi, the gold tablets on display at the Villa Giulia, late sixth century BCE. On either side are the gilded nails found deposited along with them. Photo adapted from Sailko on Wikimedia Commons.

5.2. Drawing of the bronze lamina inscribed in Etruscan from the temple of Tinia at Marzabotto. Drawing © Elisabetta Govi.

5.3. Umbrian inscription on a bronze tablet, one of the so-called Iguvine tables. Photo adapted from Wikimedia Commons.

113

114

117

131

135

137

141

142

145

157

161

175

178

181

5.4. Terracotta tile with calendrical inscription from Capua. Image © Antikensammlung, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin – Preussicher Kulturbesitz (Photograph by Johannes Laurentius, inventory number 30892). 192

5.5. Etruscan inscription on a bronze disc-like object from Magliano, Tuscany. Image adapted from Wikimedia commons. 195

5.6. Terracotta iuvilas stele with Oscan inscription from the sanctuary at the site of Fondo Patturelli, Capua. Image © Trustees of the British Museum. 197

5.7. Bronze tablet from Agnone, Molise, with Oscan inscription on both sides. Image © Trustees of the British Museum. 207

6.1. Drawing of painted scene from tomb on the Esquiline, Rome, showing encounter between Samnites and Romans. Image adapted from the Bullettino della Commissione Archeologica Comunale di Roma 17 (1889) tb. 11–12. 221

6.2. Scene of combat between Italian heroes from the wall of the François tomb, Vulci. Adapted from Wikimedia commons. 224

6.3. Plan and cross-section of François tomb, Vulci. Adapted from Wikimedia Commons. 226

6.4. Detail of Vel Saties from the painting of the frescoes of the François tomb. Adapted from Wikimedia Commons. 229

6.5. Processional scene from the Tomb of the Conference (tomba del convegno), Tarquinia. Photograph by Gaetano Bellucci, image © by Alessandro Naso. 235

6.6. Drawing of banqueting scene from tomb of the shields, Tarquinia. From Monumenti inediti pubblicati dall’instituto di corrispondenza archeologica. Supplemento (Berlin 1891). 236

6.7. Andriuolo necropolis, Paestum, Tomb 12A. The return of the warrior, 380–370 BCE. Image © Parco Archeologico di Paestum e Velia / Ministero della Cultura.

242

6.8. Cumae, painted slab from a tomb, Benassai 2001 no. Cu.13, ca. 300 BCE. Drawing by author modified from Benassai 2001. 243

6.9. Andriuolo necropolis, Paestum, Tomb 114, north wall. Battle scene, 330–320 BCE. Image © Parco Archeologico di Paestum e Velia / Ministero della Cultura. 246

6.10. Spinazzo necropolis, Paestum, Tomb 1, back wall. Older male individual, ca. 320–300 BCE. Image © Parco Archeologico di Paestum e Velia / Ministero della Cultura.

249

6.11. Terracotta relief probably from a funnel vase, identified as Canosan. Metropolitan Museum of Art 12.232.10, image in the public domain. 252

Maps

1. The Italian Peninsula showing ancient regions and cultural areas. Location of Maps 2–4 indicated by boxes. Drawn by author with base GIS and hillshade data from EEA and place locations from Pleiades and Google Earth. vii

2. Northern Italy and the Po Valley showing location of sites mentioned in the book. Drawn by author with base GIS and hillshade data from EEA and place locations from Pleiades and Google Earth. viii

3. Central Italy and the Tiber Valley. Drawn by author with base GIS and hillshade data from EEA and place locations from Pleiades and Google Earth. viii

4. Southern Italy and Magna Graecia. Drawn by author with base GIS and hillshade data from EEA and place locations from Pleiades and Google Earth. ix

Preface and Acknowledgments

I began the groundwork for this book several years ago when researching a paper on some Campanian tomb paintings. It became clear that not only those paintings, but a rich corpus of archaeological evidence, revealed a deep and abiding interest in history on the part of the peoples of pre-Roman Italy, and a book-length study was in order. Recently discovered sites like the “funerary chapel” at Veii or the “house of the king” at Populonia offered spectacular material of this sort but were so far mostly known to prehistorians, while it seemed to me that these discoveries merited a broader audience. My thoughts on the subject came together fairly rapidly in 2020, after the global pandemic ended the possibility of planned archaeological fieldwork. Meanwhile, world events were pointing out with greater urgency some very longstanding issues within the discipline of classical studies, which by tradition in North American universities houses both archaeology and ancient history as they apply to the Greco-Roman Mediterranean. It seems to me that there is considerable value in telling more ecumenical stories of the many ways in which ancient people engaged with their pasts. In starting the work of building a place for our discipline in a more just world, we are confronted with the traditional centrality to classical studies of the text. There are of course many illuminating ways one can approach texts as sources of historical information about non-traditional segments of ancient society, and much productive work continues in this direction, but in the end the fact remains that the historiographical tradition with which Roman historians work is largely an artifact of elite Roman imperial culture, and its study is often, whether consciously or not, reproductive of that character. Therefore, a critical discussion of some of the attitudes and ideologies that I feel are implicit in binding ancient history to historiography seems essential and timely. And because there is little point in mere criticism, I also hope this book opens up some new paths forward in our understanding of the non-textual intellectual and cultural histories of Italy and Republican Rome.

Stuck at home like most of us over the last few years, I have been sustained by communications with a community of friends and colleagues. I am grateful for the generosity of those who took time to share work and ideas,

Preface and Acknowledgments

or offer thoughts, disagreements, and encouragement on the manuscript. I thank Jeremy Armstrong, Maria Cristina Biella, Massimiliano Di Fazio, Lisa Fentress, Alison Keith, Lisa Mignone, Sarah C. Murray, Dimitri Nakassis, Dan-el Padilla Peralta, Charlotte Potts, Andrew Riggsby, and Angela Trentacoste. A number of scholars generously helped with images: Giovanna Bagnasco Gianni, Gilda Bartoloni, Marco Fabbri, Elisabetta Govi, Alessandro Naso, Silvia Paltineri, Corinna Riva, Nicola Terrenato, Anthony Tuck, and Joachim Weidig. John Hopkins sent me dense, useful notes on the whole text, shared thought-provoking work of his own, and assisted with images. Emlyn Dodd helped with map-making. Papers in either manuscript or published form sent to me by Marco Maiuro and Brian Rose provided important sparks for my own thinking at various points. It has once again been a pleasure working with Oxford University Press, and I warmly thank Stefan Vranka. I single out two people in particular for thanks. To Duncan MacRae, I owe my initial awareness of the anthropological literature that forms the project’s critical frame. Duncan was also the first person to look at the project in draft, and his enthusiastic encouragement carried me through the rest of the process. And I am especially grateful to Christopher Smith: attentive readers will see how frequently he is mentioned in the footnotes, as he could have written this book himself. He has been an unstinting supporter, mentor, and friend.

I dedicate this book about the social construction of the past, present, and future to my family, who will always form the sturdiest way for me to anchor my own place in time: Alexa, Livia, Jonathan.

Introduction

The problem now is to explode the concept of history by the anthropological experience of culture. Heretofore obscure histories of remote islands deserve a place alongside the self-contemplation of the European past—or the history of “civilizations”—for their own remarkable contributions to an historical understanding. We thus multiply our conceptions of history by the diversity of structures. Suddenly, there are all kinds of new things to consider.

Marshall Sahlins (1983: 534)

This book describes the historical culture of Italy from the Early Iron Age to the Roman conquest, covering a period from roughly 900 to 300 BCE. By historical culture, I refer throughout to a broader concept of social engagement with the past than is sometimes meant by the word “history.” But this move permits us, following Sahlins’ suggestion, to consider all kinds of new things. There exists a substantial corpus of material, much of it archaeological, some of it newly discovered, that speaks to us about how local communities in early Italy thought and talked about their history and how they articulated their past and present. This material has yet to have much impact on the typical ways in which we reconstruct the process of “becoming historical” in Italy.1 Instead, the story tends to be told almost exclusively from the Roman perspective and in a teleology that seeks to explain the emergence of written history at Rome around 200 BCE, or slightly earlier in the hands of some Western Greek authors. These are neither unimportant nor uninteresting developments, but this book intends to show that they can be illuminated by expansion. The rise of historiography is by no means the only way that Italians were engaging with their past in this period; and while the one story is by now well studied, Italians’ own historical interests remain far less so,

1 For the phrase, Purcell 2003.

Historical Culture in Iron Age Italy. Seth Bernard, Oxford University Press. © Oxford University Press 2023. DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780197647462.003.0001

aside from select topics like the existence of Etruscan historiography, or the contribution of Italian precedents to Roman interests in historical imagery.2 I set out here to provide a systematic study that portrays Italians’ historical interests as a much longer-term and deeper development.

In the intellectual and cultural history that follows, Rome plays a part, but not a leading one, and more importance is given to the influence on historical thought of social structure and urbanization. A driving theme of this book is how the emergence of urban society in Iron Age Italy prompted new modes of historical thinking. This is therefore adamantly not a book about Roman history or Roman historiography, but my hope nevertheless is to offer some value for those thinking about historical practices at Rome during the Republican period. Recent research by Denis Feeney among others emphasizes the unusualness of Romans’ turn, starting in the fourth century, to Greek models to create their own literary culture, a turn that includes the initial elaboration of written Roman history.3 There was nothing obvious or predictable about Romans’ decision to develop a Greek-style literary culture, but the move was highly conscious and deliberate, and also highly contingent upon the particular sociopolitical circumstances of that period. This research has been enormously successful in challenging some longstanding assumptions about cultural developments in Republican Italy. What remains to be done, and what this book sets out to do, is to show the richness and long-generating characteristics of Italy’s own historical culture on the eve of such developments. In doing so, my intention is not to argue that Italy’s intellectual developments directly influenced the creation of written history in the hands of the first Roman historical authors, Fabius Pictor and his peers. Rather, I seek to cast light upon the extraordinary and dynamic historical culture that existed among the peoples of Italy for centuries beforehand. The resulting implication, I think, will be to emphasize what others studying Roman Republican literary culture now suggest: that Romans’ trajectory of cultural development and their turn towards written history was anything but obvious.

Some readers may already be asking the question: what do I mean when I refer in this book to “history”? As I discuss in detail below, Italians never seem to have created a robust tradition of written historical narrative of their own. To insist that Italians also had historical culture thus demands

2 Both these themes are discussed below in Chapter 6; for Etruscan historiography, see Cornell 1976; for Italian influences on Roman artistic style, see Torelli 1997.

3 Feeney 2016; see also Purcell 2003; Goldberg 2005.

a different understanding of what constitutes history. For thinking about these questions, I turn especially to the work of Marshall Sahlins, who spent considerable effort contemplating one of the cruxes of anthropological theory: the relationship between ahistorical structure and historical events in shaping human experience. In turn, this interest implied Sahlins’ longstanding engagement with history itself, but always from an anthropological perspective, leading him to consider historical production as to some extent culturally specific. In 1983, Sahlins influentially coined the phrase the “anthropology of history” and declared that the “different cultural orders studied by anthropology have their own historicities.” In subsequent studies, Sahlins drew attention, for example, to how features of Thucydides’ account of the Peloponnesian war between Athens and Sparta resembled Fijian accounts of the Polynesian wars of the nineteenth century. Of course, the Greek historian’s written, narrative account is strikingly different in both medium and content from High Fijian Genealogy, an orally transmitted tradition structured around kings and their descendants. Despite their great distance in time and space and despite very different cultures of history, however, both societies used the past to construct their respective social orders in surprisingly overlapping ways.4 As I return to later in this chapter, the basic point is that different cultures have different modes of historical production, and modes that are perhaps at first glance less familiar to us nevertheless remain valid and effective forms of history.

These ideas intend to provide some contours to this book’s definition of historical culture: I doubt that many readers will be surprised to discover that early Italians were actively interested in their past, but their modes of historical production studied here can sometimes look different to us. For that reason, Italian historical culture remains comparatively understudied. The other implication of this anthropological perspective is to see this historical culture as closely bound up within the fabric of Italian society. The way Italians went about articulating past and present thus becomes a reflection of their developing social structures. One could turn this around: in many ways this is a book about the history of Italy before Rome, but one told from the particular perspective of developments in Italians’ sense of their past. Of course, this limited lens means that I do not claim here to offer a complete cultural history of Pre-Roman Italy, but this book does intend to take a

4 Sahlins 1983; see also Sahlins 1981, 1985, 2004. For the influence of his work in this area, see Palmié and Stewart 2016.

step in that direction. By starting from the recognition that historical culture is contingent, we can approach Italian societies in part by asking how they constructed their history.

For the remainder of this introductory chapter, I want to explore in greater detail some of these aspects: what the practice of history in Italy was like, how modern scholarship has understood it, and how a broader and anthropologically inflected concept of historical culture can help challenge in a productive manner some of our assumptions about Iron Age Italy’s cultural development. I have already broached the difference between written and oral history, and this binary will be important throughout this book. However, I want to begin discussion by insisting that this book is not simply about oral modes of historical production; the differences I intend to describe are more cognitive than simply technological. A fundamental challenge this book intends to pose is for modern historians to reassess tendencies to understand ancient historical production primarily as narrative and arranged according to linear, universal time—these ideas have become very deeply rooted in scholarship about ancient Italy and Rome to the extent that they sometimes color expectations, making otherwise relevant evidence seem less so. Of course, the use of writing is not unrelated to narrative or particular temporal arrangement, but written texts can, I think, be historical without possessing such characteristics. To illustrate this, let us consider an Italian text: the monumental sarcophagus of Laris Pulenas from late third-century BCE Tarquinia depicts on its lid a reclining portrait of the deceased holding an unrolled scroll filled with a long inscription (Figure 1.1). The sarcophagus and its inscription was found in 1878 along with almost two dozen other sarcophagi in Laris Pulenas’ family’s tomb.5

The nine-line text, among the lengthier extant Etruscan funerary inscriptions, begins as follows:

(This is the sarcophagus of) Laris Pulenas, son of Larce son of Larth, grandson of Velthur, great-grandson of Laris Pule the Greek—who wrote this book on divination. He held the office of creals in this city, Tarquinia . . . 6

5 For the discovery, Helbig 1879: 78–84. Sordi 1960: 177–82; Mazzarino 1966: 86–87; Harris 1971; Cornell 1976; Cornell 1978; Heurgon 1961: 275 discuss this text in relation to Etruscan sacred, not historical, writing; Hadas-Lebel 2016 connects it to other historical inscriptions from Etruria like the Spurinnae elogia

6 ET Ta 1.17: l(a)ris. pulenas. larces. clan. larθal. papacs. velθurus. nefts. prums. pules. larisal. creices. ancn. ziχ. neθσrac. acasce. creals. tarχnalθ. spurem. lucairce. ipa. ruθcva. caθas. hermeri. slicaχem. aprinθvale. luθcva. caθas. paχanac. alumnaθe. hermu. Mele. crapisces. puts. χim. culsl. leprnal. pσl.

Figure 1.1 The sarcophagus of Laris Pulenas. Tarquinia, late third century BCE. Image adapted from Vianduval on Wikimedia commons, used with the kind permission of the Parco Archeologico di Cerveteri e Tarquinia.

Only the first few lines of Laris Pulenas’ inscription, about to where my translation ends, are easily rendered into English. The specific meaning of the remainder is debated, but by all accounts the text continues with a long list of offices and priesthoods held by the deceased.7 Still, the opening is enough to signal Laris Pulenas’ interest—or his descendants’ interest—in his family’s past through its commencement with an extensive family tree, which names four generations of ancestors. The list goes all the way back to a progenitor who, as Jacques Heurgon first argued, emigrated from Greece to Tarquinia around the time of Alexander the Great.8

Laris Pulenas’ dress and appearance, as well as reference in the text to his priestly writings and offices, confirm that he belonged to Tarquinia’s religious

varχti. cerine. pulalumnath. pul. hermu. huzrnatre. psl. tenin[e. . . . .]. meθlumt. pul. hermu. θutuiθi. mlusna. ranvis. mlamna[. . . . . .]mnaθuras. parniχ. amce. leσe. h(e)rm(e)ri{er}

7 Morandi 2004: 390–94; Belfiore 2011; Hadas-Lebel 2012; Hadas-Lebel 2016.

8 Heurgon 1957.

and political elite. The letters of the inscription still show traces of red coloring or rubrication, which would have made them visible, and from the proud way his statue displays the scroll to the viewer, we see how this genealogical past constituted a particular point of pride and source of authority. Laris Pulenas’ inscription, with its combination of ancestry followed by personal accomplishments, presents some similarities with well-known Roman epigraphic texts on sarcophagi of around the same date, especially the funerary inscriptions of the Cornelii Scipiones from their family tomb just outside the city of Rome. The earliest two Latin inscriptions (elogia) from the tomb of the Scipios may have been composed around the same time as the Laris Pulenas inscription and reveal a similar textual structure of personal name followed by filiation then civic achievements. Compare the earliest funerary text (elogium) of Lucius Cornelius Scipio Barbatus:

Cornelius Lucius Scipio Barbatus, born to his father Gnaeus, a brave and wise man whose appearance was equal to his virtue, who was consul, censor, aedile among you; he took Taurasia and Cisauna in Samnium, conquered all Lucania, and led away hostages.9

There are important differences of content between this document and that of Laris Pulenas, some of which can be ascribed to local artistic and cultural habits, or to differing historical circumstances. Still, the basic structure of both inscriptions bears noticeable resemblance. Both documents start with names and lineage and then follow with local accomplishments. Both display conscious interest in recording the past as a vehicle for prolonging the memory of the individuals to whom they refer, and both use that past to stake claims about the deceased’s role in the continuing social orders of their communities. In scholarship, the Scipio Barbatus text is regularly cited as background to the emergence of Roman historical writing, while Laris Pulenas’ text receives far less attention as such.10 What might be the cause of this imbalance?

I would identify two responsible methodological issues, one broad and one narrow. The first concerns a scholarly opinion, prominent especially among influential thinkers of the last century, that genealogy is not history. In a 1966

9 CIL VI 1284: Cornelius Lucius Scipio Barbatus, Gnaivod patre prognatus, fortis vir sapiensque quoius forma virtutei parisuma fuit, consul censor aidilis quei fuit apud vos, Taurasia Cisauna Samnio cepit, subigit omne Loucana, opsidesque abdoucit

10 But see now Hadas Lebel 2016.

paper on time in ancient historiography, Arnaldo Momigliano dismissed biographical or genealogical time as inappropriate for ancient history. Greek and Roman historians were concerned with events and their reliability, and consequently the ability to test historical schema through synchronization was especially important.11 Based as it was upon the non-universal units of family generations, in his view, genealogy could not withstand the scrutiny required by proper history. His opinion shares, unconsciously so far as I can tell, a great deal with E. E. Evans-Pritchard’s classic anthropological exposition of the Nuer people of Sudan, published in 1940, in which he argued that genealogy was not history because it was “less a means of co-ordinating events than of co-ordinating relationships.”12 By extension of this sort of logic, we might surmise that the reason that historians remain interested in the epitaphs of the Cornelii Scipiones is not for their inclusion of ancestry, but for their proximity to the first written Roman histories of Fabius Pictor and his successors, who are assumed to have transformed this sort of material into historiography. If there is “no history without archives,”13 then these epigraphic texts might reveal what archival material may have looked like at a key moment in the development of Roman historiography. Following the same logic, in Etruria, where we are less certain how or when written historiography developed, if it ever did, what archival material we possess becomes less interesting.

There has recently started to be pushback to the opinion that genealogy is distinct from history as properly conceived, however, and we would do well to join such challenges.14 The view of earlier scholars like that of Momigliano or Evans-Pritchard reveals a notion of history as something distinct from other ways of engaging with the past because it is constructed upon a specific conception of time that is not measured in terms of human relationships but is instead “statistical . . . oriented and non-reversible.”15 But why must history always display such qualities?16 For one thing, ancient peoples of the Central Mediterranean do not seem to have prioritized them in their own engagements with the past. Instead, a surplus of material would suggest that genealogy was one of the more common ways in which people

11 Momigliano 1966, esp. 14.

12 Evans-Pritchard 1940: 108.

13 Goody 1977: 147.

14 For response to Momigliano, see Clarke 2008: 15–16; for response to Evans-Pritchard, see Shryock 1997: 21.

15 Lévi-Strauss 1958/1972: 286.

16 Provocatively, Tanaka 2015 argues for divorcing the concepts of history and chronology.