Tire and Vehicle Dynamics Hans B.Pacejka

https://ebookmass.com/product/tire-and-vehicle-dynamics-hans-bpacejka/

ebookmass.com

Personal Finance 12th Edition, (Ebook PDF)

https://ebookmass.com/product/personal-finance-12th-edition-ebook-pdf/

ebookmass.com

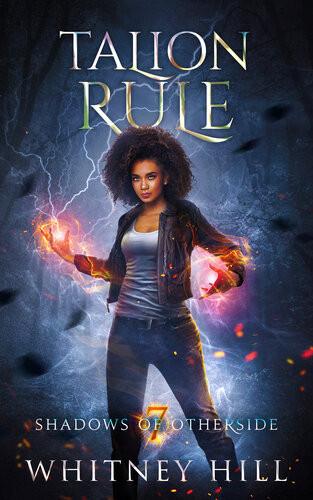

Talion Rule Whitney Hill

https://ebookmass.com/product/talion-rule-whitney-hill-3/

ebookmass.com

Coop Knows the Scoop Taryn Souders

https://ebookmass.com/product/coop-knows-the-scoop-taryn-souders/

ebookmass.com

The Book of Real-World Negotiations: Successful Strategies from Business, Government, and Daily Life Joshua N. Weiss

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-book-of-real-world-negotiationssuccessful-strategies-from-business-government-and-daily-life-joshuan-weiss/ ebookmass.com

Thomas Hamblin and the Bowery Theatre: The New York Reign of "Blood and Thunder” Melodramas 1st Edition Thomas A. Bogar (Auth.)

https://ebookmass.com/product/thomas-hamblin-and-the-bowery-theatrethe-new-york-reign-of-blood-and-thunder-melodramas-1st-edition-thomasa-bogar-auth/ ebookmass.com

Historic Churches of New Mexico Today

Historic Churches of New Mexico Today

Frank Graziano

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

© Oxford University Press 2019

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

CIP data is on file at the Library of Congress

ISBN 978–0–19–066348–3 (pbk.)

ISBN 978–0–19–066347–6 (hbk.)

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Paperback printed by Sheridan Books, Inc., United States of America Hardback printed by Bridgeport National Bindery, Inc., United States of America

COVER PHOTO CREDIT:

Cover photograph by Carol M. Highsmith. San José de Gracia Church in Las Trampas, New Mexico. Courtesy of Photographs in the Carol M. Highsmith Archive, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

In memory of truth.

PREFACE

Ihad in mind a book that would focus less on church buildings than on people in relation to churches—parishioners, caretakers, priest, restorers—and on what is happening at historic churches today. The themes that emerged as I pursued this concept included the interactions of past and present, the decline of traditions, a sense of place and attachment to place, the church as a cultural legacy, the church in relation to native traditions, resistance to Catholicism, tensions between priests and congregations, maintenance and restoration of historic buildings, and, in general, how the church as a place and devotion as a practice are important (or not) to the identities and everyday lives of individuals and communities.

My original intent was to write ten chapters in a standardized format, with each chapter devoted to a single church. As the project developed, however, I realized that a limited sample would inadequately represent the scope of New Mexican church communities and the complexity of the themes that they evoke. Interrelations and regional clusters of churches also made the original approach seem unviable. Rather than forcing a consistency that the project was resisting, I decided finally to allow the nature of the material to determine the structure of each chapter. Five of the chapters follow the original single-church format and include a visiting guide and “present past” section that summarizes a historical event of current relevance. Two chapters provide interpretive tours of chains of churches, one along the High Road to Taos and the other along the southern Río Grande, with historical context as necessary. One chapter, on Mora County, treats a group of regional churches collectively. Late in the project I also added an appendix so that churches not treated elsewhere in the book could be included at least briefly.

The principal historic churches in Albuquerque and Santa Fe are mentioned in that selection but are otherwise excluded, in part because information on these churches is widely available elsewhere. I also confess a rural bias.

My focus is on the “today” of the book’s title, but during the research it became clear that a measure of history would be necessary to inform and enhance what we see presently. Consequently I integrated historical narrative as it seemed useful to current understanding, or to clarify matters that are undertreated or unclear in other sources. I also included a chapter that summarizes deculturation policies during the Spanish, Mexican, and American governance of New Mexico and then details conflicts with the Archdiocese of Santa Fe at Santo Domingo (Kewa) and Isleta Pueblos. Throughout the book I have avoided the boilerplate history that seems to me more a baggage of knowledge than a contribution to true understanding.

The range of topics treated in the book required a corresponding range of discourse—narrative, descriptive, interpretive, guidebook—as the occasion warranted. I allowed myself shifts of register accordingly and tried to keep the transitions from being too abrupt. At some moments I wanted to capture experiential qualities and to reproduce their feelings in language.

Unlike my previous books, which each had several hundred endnotes, in this work I kept the scholarly apparatus to a minimum. The intent of the brief notes is to acknowledge the sources that contributed to my interpretation rather than to reinforce an argument or facilitate subsequent scholarship. Eventually I reduced the bibliography to include only works cited in the notes so that the page space could be used to better purpose.

My approach throughout the research was to read with depth and breadth in order to establish a context, and then to base the chapters primarily on interviews with people active at the churches. These informants are identified by first names only. Rather than guiding the interviews with imposed themes from the readings or from my own thoughts, I introduced ideas and then allowed local interests and concerns—what was important to people at a given church—to emerge in the discussions. Once I found a thread I would pursue it during later interviews, and as new ideas emerged I would pursue them similarly. My intent for the book as a whole was diversity in content as well as format, with each chapter treating different themes. Many themes were common to multiple sites, however, so I consolidated treatment where it seemed most appropriate and then allowed echoes in other chapters to recall and reinforce a given theme.

The book that resulted from this method is largely about the people I interviewed and the experience of being among them. The research was a moving opportunity to interact with lives remarkably different from my own.

Ethnography is to a certain degree duplicity—who you are and who you are outside your culture—until ultimately the doubling collapses and you wonder where that leaves you. I spied on myself within the mysterious sphere where differences meet and negotiate a relation, and where I saw myself through others, learned from that, and formed friendships. Mostly I admired people’s certainty—their confidence in being who they are—and I was also moved by their commitment, humility, and generosity delivered with a human warmth that I had almost forgotten. I also admired the informants’ insightfulness, which shamed the empty academic verbiage to which I had assimilated. This book, more so than any of my others, is written in the point of view of the people I interviewed.

The churches in the title and throughout the book refer to Catholic churches. “Pueblo” in the lower case refers to a native village, and in the upper case to the people, the Pueblo Indians. I use “Indian” as opposed to “Native American” following local usage at the pueblos, in New Mexico more broadly, and in the titles of major institutions, such as the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture and the Indian Pueblo Cultural Center. Racial and ethnic adjectives—black, hispanic, native, white—are used in lower case. Once a context has been established, I generally refer to Penitentes—members of la Fraternidad Piadosa de Nuestro Padre Jesús Nazareno as “hermanos” (which means brothers—a fraternidad is a brotherhood) or for clarity as “hermanos penitentes.” These are used in the lower case, as is “penitente” as an adjective. All roads are designated as “route” to simplify the multiple variations— state road, county road, tribal road, forest service road.

The word “mission” has two distinct meanings. One refers to the Franciscan missions and their churches to convert the Pueblos beginning in the late sixteenth century. The other meaning is a parish designation for affiliate churches: Each parish has a pastor (the priest responsible for the parish) at a main or mother church, and this pastor is also responsible for one or more additional churches, known as missions or mission churches, located elsewhere. I use “mission” in both of these senses, which are clear in context.

Iglesia means church, capilla means chapel, santo and santa mean saint and are also used in reference to images of saints, and san is an abbreviation before the names of some saints (San Francisco, San Isidro). To avoid the unfortunate word reredos, which seems plural in the singular and is awkward in the plural (reredoses), I use “altar screen” for the painted panels that are behind altars and sometimes positioned laterally along naves. New Mexican altar screens are usually comprised of retablos, here meaning images of saints painted on wood. Bultos are carvings of saints in wood. Santeros and santeras are people who paint retablos and carve bultos, which is to say make

images of saints. An encuentro (literally “meeting”) occurs when two saint images are brought in procession to meet one another, or in another use when people from a local church come out to meet an arriving pilgrimage or procession. A mayordomo or mayordoma is a person (or in the plural often a married couple) designated as church caretaker; the Pueblos also use church mayor, fiscal, and gaugashti to designate this role. A función is technically the annual installation of new mayordomos, although the same mayordomos often continue, and the corresponding mass and celebration are usually on or near the patron’s feast day. A convento, unlike the English cognate, refers to the friary or priest’s residence at a mission church. I use “apse” as the exterior rear of the church, “chancel” as the altar area, and “atrium” as the open area, often walled, in front of a church. There are regional differences in the use of luminaria and farolito, and the words are sometimes used interchangeably. I use luminaria in reference to the (often piñón) bonfires at many night events, and farolito in reference to the votive candles inside paper bags that are used as decoration at Christmastime.

It was difficult to standardize accents in the Spanish names of people and places, because in New Mexico accents are used inconsistently. In the end I privileged the Spanish to the anglicized spelling and put accents everywhere that Spanish required, with exceptions to follow standard usage or an individual’s personal preference.

The churches described in this book are predominantly active places of worship. Visitors are expected to be respectful and abide by posted rules. Protocols for visiting Indian pueblos are widely available in print and online and are strictly enforced. Many of the religious events that I describe are not frequented by tourists, and in some cases a visitor might be the only person present from outside the community. In these circumstances appropriate behavior is generally reciprocated with a warm welcome. The dates and times of masses, feast-day celebrations, openings, and other events change frequently, and at many village churches masses and feastday events are irregular or being discontinued. Parish and pueblo offices (and sometimes websites) have current information. Churches at other times are usually locked, but parish office personnel will sometimes unlock a church for visits upon request. At some places a donation or purchase of a raffle ticket is expected in return, and at all historic churches contributions are needed and appreciated. Often there is a collection box for this purpose.

In the visitor sections of this book I have excluded all information that might change periodically, such as phone numbers, event times, and sources of food and lodging. Simple directions are provided where

GPS guidance might be insufficient or inaccessible. Dirt roads should be avoided when wet, because in many areas of New Mexico the clay content of dirt clogs tire treads and makes driving feel similar to sledding. Many dirt (and paved) roads also cross arroyos or dry stream beds that are prone to flash flooding during upstream storms. It is always best to inquire locally regarding road conditions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

My greatest debt is to Allison Colborne, director of the Laboratory of Anthropology Library at the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture in Santa Fe, for her help and solidarity from the beginning and throughout the project. Diane Bird, the archivist at the same institution, generously facilitated contacts and guided me as I found my way. I am also most grateful to Nicole Kliebert, formerly of Cornerstones Community Partnerships, to Father Jack Clark Robinson, OFM, provincial minister of Our Lady of Guadalupe Province, and to photographer John A. Benigno, all of whom kindly provided help and guidance at various stages of the project.

In Chimayó and along the High Road my research was greatly enhanced by the help of Father Julio González, Angelo Sandoval, Lorrie García, Ben and Annette Smiley, my friends and neighbors Clodie François and Barbara and Weto Malisow, and especially Frank López.

At Laguna Pueblo I gratefully acknowledge Governor Virgil Siow and Tribal Historic Preservation Officer Gaylord Siow, whose support of the project made research at the pueblo possible and pleasurable. I am also grateful for the help and guidance of Antonio Trujillo and Father Gerry Steinmetz, OFM.

At Acoma Pueblo I am very grateful to Second Lieutenant Governor Chris Garcia and Tribal Secretary Marcus Leno, who kindly guided my navigation through the procedures for requesting research permission from the tribal council.

At St. Joseph Apache Mission Father Mike Williams warmly welcomed my research, and I am especially grateful to Harry Vasile for his friendship and help throughout my stay in Mescalero.

In Mora County, Veronica Serna introduced me to the community of mayordomos and thereafter helped to arrange interviews. Rebecca Montoya was a great friend throughout my Mora research and thereafter during many meals and excursions. I am also grateful to Father Dennis Dolter, who endorsed the project, and for kind assistance along the way from Pete Warzel, Mac and Kristin Watson, and Gabriel Meléndez.

In Golden, Desiri and Allen Pielhau, of the Henderson Store, very kindly provided documents, news articles, digital files, and photographs that were critical to my research. Tom Chávez also generously shared information based on research he had done in the 1970s. Ron Cooper and the Franciscan Archives of the Province of St. John the Baptist, in Cincinnati, graciously provided documents and photographs.

The many people who took the time to talk with me, share their experiences, and show me their churches have each been thanked personally, but I reiterate my gratitude here formally and for the collective.

I do so likewise for the archivists and librarians who assisted my textual research, especially Patricia Hewitt, formerly of the Fray Angélico Chávez History Library. Other collections and institutions that were essential during the research (in addition to the Laboratory of Anthropology mentioned above) include the University of New Mexico’s Center for Southwest Research and Special Collections; the New Mexico State Records Center and Archives; the New Mexico State Library; the New Mexico State University Library Archives and Special Collections; the Southwest collections at Taos Public Library and Santa Fe Public Library; the Ben Lujan Library at Northern New Mexico College; Our Lady of Guadalupe Province Archives; the Palace of the Governors Photo Archive; and the Bartlett Library and Archives at the Museum of International Folk Art.

The sources of photographs are acknowledged in the captions; those without attribution were taken by me.

I acknowledge an aesthetic debt to the works of Cormac McCarthy, Bruno Schultz, Gustaw Herling, and Fernando Pessoa.

And finally, to Cynthia Read, my editor at Oxford University Press since 1998, I express again my enduring gratitude.

1 Santuario de Chimayó

Life is a journey and you choose to be a pilgrim or a tourist.

Some come wounded by disease, by addiction, by broken hearts or even simply besieged by the malaise of emptiness and loss of hope and by human frailty in quest of some durable meaning. I’m not sure why I’m here. Maybe in repair from the normalized insanity that makes your footing wobble and your background recede until you stand alone stranded with hands on your ears but still feel the tremble inside your body.

An old man with a red cap in his hand limps with a cane toward the Santo Niño de Atocha. He drops some coins in the box, looks at the kneeler to calculate the challenge, and kneels slowly, favoring one leg, really more of a genuflect, and after a wince of pain and gravitational surrender he settles and signs himself with the cross. The Santo Niño is enshrined in a nineteenthcentury confessional booth painted white, with holes drilled more or less in pattern to form an imperfect circle on the sides. The front, at the top, above the praying man’s head, has a disproportionate pilgrim’s shell carved in wood. As the man prays a family passes behind him to gather holy dirt in the room just beyond. Through the doorway you can see a circular hole in the floor and trowels at angles in dirt toplit to dramatic effect. The mother shovels a heavy load into a Walmart bag and the family leaves—there didn’t seem to be prayer involved—just as bus tourists wearing nametags approach behind a guide with an umbrella. Hats, backpacks, and phone cameras mobilized by new sneakers bought for the trip.

Chimayó, where the santuario (the Spanish word for shrine) is located, is a composite of several settlements, historically known as plazas. The santuario was built in the Plaza del Potrero, which consequently evolved to

Father Julio

become the epicenter of Chimayó as it is known today. The nearby Plaza del Cerro is one of the few remaining remnants of the fortified plazas that were built to settle rural New Mexico. Chimayó is in a valley at the base of one of four regional hills that were sacred to the Tewa prior to conquest. In Tewa the hill is known as Tsi Mayo, from which the hispanicized place name was derived. There are several native ruins in the area, and many residents believe that what is now holy dirt was once curative water (or mud) used by the Tewa. Such Christianization of a native healing site or medium occurred frequently in colonial Mexico, to which New Mexico belonged, usually after a miraculous apparition. During a smallpox epidemic in Tlaxcala, the Virgin of Ocotlán led natives from their traditional curative water to a more effective Christian alternative. That spring is now inside a chapel connected to this Virgin’s basilica by a walkway.

The Santuario de Chimayó was built after a painted wooden sculpture of the Christ of Esquipulas appeared miraculously at the site where the holy dirt is now gathered. This crucifix was discovered around 1810 by Bernardo Abeyta (1771–1856), a regional leader of the Penitentes. Construction of the chapel began around 1813 and was completed in 1816. An 1818 inventory describes the church’s adjacent rooms as warehouses for local woven goods, probably stocked there for sale to visitors. The two rooms at the entry—now the priests’ office on the left and the Blessed Sacrament Chapel on the right— were recorded in a 1934 Historic American Building Survey as “storage” and “unused,” respectively.

At the time of the santuario’s construction and well into the twentieth century, the houses in the Plaza del Potrero were residences inhabited by families that had settled the area. Today many of the houses are shops or abandoned. Dennis remembered that even some fifty years ago, when he married into the community, “the houses were occupied, there were kids playing, dogs. You walk out there today and this is a ghost town.” Originally the shrine and holy dirt were used by local and then regional residents who came to seek miracles related primarily to health. As described in a Works Progress Administration (WPA) report in the 1930s, “Crippled and suffering men, women and children, sometimes as many as one hundred in a single day, come to the santuario on foot, horseback, in carriages, wagons or astride burros.”

Tourists with cars began to arrive early in the twentieth century too, but the volume was moderated by the difficulty of access. One woman traveled to the santuario with her husband in the mid-1930s and later wrote about the experience. After turning from Española onto what is now Route 76, she wrote, we “traveled something more akin to a trail, twisting to the right, then

to the left, and with plenty of curves up and down . . . . Sometimes the road seemed to disappear entirely; there were dips so abrupt that the up-coming sensation was breath-taking; rocks were abundant and once, for a considerable stretch, our way apparently lay straight up the dry bed of a creek.” This stretch of Route 76 from Española through Santa Cruz was later paved and recently designated the Father Casimiro Roca Memorial Highway, after the pastor who was largely responsible for the santuario’s initial development. Father Roca was intermittently a pastor and priest at the santuario from 1959 until his death in 2015. “When I first arrived,” he wrote, “I found the structure of the church in danger of crumbling into ruins.” In September, 2017, a statue of Father Roca, sculpted by Marco Oviedo, was installed on the santuario grounds.

Route 98 was another dirt lane across difficult terrain until it was paved around 1964 through the advocacy of a former county commissioner, Juan Medina. His son, Leroy, later petitioned successfully to have Route 98 named Juan Medina Road. The paving of that road greatly facilitated access to the santuario, because the road intersects on one side with Route 76, which leads to Española, and on the other side with Route 503, which leads to Pojoaque and Santa Fe. The paving of Route 98 also contributed to development of

Pat shares a laugh with Father Julio and others during the unveiling ceremony for the Father Roca statue.

the scenic route known as the High Road to Taos, on which the santuario became a principal stop.

Shortly after these transportation improvements, in 1970, the santuario was designated a National Historic Landmark. The paved routes, the honorific historic designation, and the growing national reputation as a pilgrimage shrine dramatically increased visits to the santuario in subsequent decades. Father Roca and the current pastor, Father Julio, have faced the challenge of managing a world-class destination of religious, heritage, and ethnicity tourism while at once preserving the santuario’s integrity as a center of devotion.

Many locals lament the erosion of traditional culture that results from development and tourism, but times have also changed well beyond Chimayó, nationally and globally, for better or worse, and insulating a community may no longer be feasible. Older northern New Mexicans also feel a sense of despair because traditions that have endured for centuries and that seemed inviolable are now depreciating or are disregarded. Leroy said that religious values used to hold people back from transgression, as a kind of checking mechanism, but many young people disrespect these values and feel free to do as they please. Drug addiction, crime, and incarceration are common consequences.

Ruben, who like Leroy grew up in Chimayó, made similar points: “They’ve lost their respect for God,” “there’s no sense of moral values,” “the respect for one another is no longer there.” He then explained that in his youth “if you did something bad in school the principal would give you a spanking with the board of education, and if your parents knew about it you’d get another one. So in a sense you would live with a sense of fear, respect. People no longer show respect for elders.” Dennis took these concerns in a different direction when he focused on the secularization of everyday life. “Every morning my mother-in-law and my wife, they’d go to the 7:00 mass, and all the people around here would go too. But nowadays, my daughters, they don’t have time to go to church, they have to get the kids ready for school and go to work.”

The angst of change and cultural insecurity in Chimayó was already apparent to the author of a 1935 report. He wrote that “the people are deathly afraid for the future. They are certain that something (they are not sure what) is going to happen to them—that they are going to lose their land or their water—that the Anglos will displace them.” Those feelings were amplified by relocation to New Mexico of artists, hippies, wannabes, and other youth— supplemented later by retirees—who were distinct in ethnicity, culture, and values from the original hispanic settlers. As described in a book published

in 1969, an initial culture shock gradually relaxed to acquiescence. “Artists sitting on a camp stool here and there sketching the santuario is not an uncommon sight, and people of Chimayó have long ceased looking upon them as odd balls with their long hair, beards, funny clothes for the most part, and have long since ceased consigning the woman to the home where she belongs, rearing a family as every good Christian woman should instead of tramping all over the countryside in men’s clothes and painting pictures.”

There are also regrets for the bucolic past undermined in part by the very roads that connected Chimayó to the world. As summarized in a Historic American Landscapes Survey, an older resident who lived along Route 76 before it was paved “used to enjoy watching the herds of sheep that passed by his house as they were moved from mountain ranches to the market in Española.” He especially loved “watching the Penitente Brotherhood file down the road between their moradas through the darkness of Lenten night.” And “he expressed a deep loss and sorrow that his home is near the road now. He detests the roar of automobile traffic.”

Esquipulas

The crucifix behind the santuario’s altar is known as Nuestro Señor de Esquipulas (Our Lord of Esquipulas) or the Christ of Esquipulas. This identity is derived from a Guatemalan miraculous image, the Black Christ of Esquipulas, which is named for the town where the statue is located. The Guatemalan image was sculpted in 1595 and is one of many Black Christs in the region. Notable others include the Señor de Otatitlán near Veracruz and the Señor de Tila in Chiapas, both Mexican miraculous images that attract huge annual pilgrimages. These Christ figures are usually black because of the dark wood used to sculpt them. Some have been darkened by candle smoke. Many of these images are crucified on what is known as a living cross, or tree of life, often green in color and with vines and leaves, to represent Christ’s triumph over death through resurrection.

As is common in devotion to miraculous images, the cult of Guatemala’s Black Christ of Esquipulas spread nationally and abroad as pilgrims, travelers, peddlers, and missionaries reported miracles. Throughout history migrants have also taken devotions with them to their new places of residence. Replicas—presumed miraculous by virtue of their relation to the original— are made and new centers of devotion emerge where these replicas are enshrined. Today devotions to images of the Black Christ of Esquipulas are in the Mexican states of Aguascalientes, Durango, Guanajuato, Jalisco, and

Oaxaca, among others, as well as at several sites in Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador, Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Panama, Venezuela, and Ecuador. In the United States devotions to the Guatemalan Esquipulas are in San Antonio, Phoenix, and Los Angeles. Unlike the Christ of Esquipulas in Chimayó, these other US images are in the likeness of the Guatemalan original. Chimayó’s Christ of Esquipulas holds in common with the Guatemalan original the name (but not appearance), crucifixion on a tree of life, and the use of holy dirt (known as tierra bendita or tierra santa) in relation to devotion. There is another New Mexican chapel dedicated to the Christ of Esquipulas in Los LeFebres, near Ocaté in Mora County.

Chimayó’s Christ of Esquipulas is one of many not-made-by-hands images, as they are called in translation of a Greek term. The idea is that these images are of divine rather than natural origin, sent by God to open a local, culturally consonant channel to his grace. There are many such images in Mexico, notably the Christ of Chalma, who appeared miraculously in a cave to displace a native deity; and the Virgin of Guadalupe, who appeared miraculously as a painting on Juan Diego’s tilma. Chimayó’s Esquipulas shares the supernatural origin of these images but not the attributes of aliveness and personhood with which miraculous Christs in Spanish America are commonly endowed. These attributes include corporal vitality and movement, expression of emotion, facial changes, sweating and bleeding, communication with devotees, and acts of volition (such as rewarding devotion and punishing transgression).

Holy Dirt

A couple of tourists bow their heads as they walk through the low doorway from the chancel, and when the man’s head rises on the other side he looks to his right and says, “There’s the dirt. I wonder if there’s bags or something.” He pulls a tissue from his pocket and the woman finds a holy-dirt informational flyer and folds it to a kind of envelope. As they leave happy with their dirt, a curious—astonished—girl follows them with her eyes but the couple doesn’t notice because their own eyes are in deep reconnaissance of the photos on the wall, the crutches, the saint images that don’t look back. Then a family of five approaches and gathers around the hole. The father makes the sign of the cross with dirt on the children’s foreheads but the family leaves when a couple of urban bicycle tourists enter, look around briefly, and then leave too. Another couple in bicycle attire enters behind

them. “That’s the holy dirt—should we get some?” the woman asks, and the man responds, “It couldn’t hurt.”

Everyone then turns toward the exterior door because an older couple is entering with an even older woman in a wheelchair that the man pushes. After stopping at the Santo Niño de Atocha they maneuver through two Mexican families, some sitting on the benches and others praying on kneelers before saints on a table. The man pivots the wheelchair to back into the little room with the dirt. He takes some dirt and makes the sign of the cross on the older woman’s forehead. When the wheelchair is moved slightly I can no longer see her but in something like shaky slow motion her bony hand and its wrist reach into the space framed by the doorway and the fingers open for dirt that mostly sifts through to the floor as the man scoops and then pours with his hand. When they wheel her out her hand is rubbing dirt inside her shirt, over the heart, and her lips are moving in prayer.

Visitors carry away the holy dirt in ziplock bags, grocery bags, paper cups, water bottles, little plastic containers sold in the gift shops, and whatever else they might have at hand. A photograph taken on Good Friday in 2003 shows dirt and trowels in a trough on the altar rail to expedite collection by devotees on a line that stretches out to the road. In anticipation of Holy Week today, young volunteers package the dirt in small plastic bags, like those used for jewelry, thousands of them, which are then distributed among pilgrims and visitors. People who cannot visit the santuario in person acquire dirt through friends, relatives, and coworkers, or request it from the santuario by phone or online and receive it in the mail. Many visitors take more dirt than they would seem to need. Frances, a mayordoma in the 1980s, joked that “maybe they are going to make adobes.”

As visits to the santuario increased, particularly beginning in the 1970s, a corner of the church was nearly undermined by people digging for holy dirt. Even decades earlier, in 1938, a WPA report noted that the hole was “already six feet deep.” To remedy the problem, around 1980 Father Roca had the holy-dirt room (and the rest of the church) paved with flagstone, forming the round hole that is seen today and known as the pocito. (Pozo in Spanish means well, perhaps in allusion to the spring of healing waters traditionally attributed to the site. Pocito is the diminutive of pozo, literally meaning small or little well, but the diminutive is also used to express affection.) Visitors today sometimes ask the priests how such a large crucifix—the Christ of Esquipulas—could have been found in such a small hole. The priests explain that when the crucifix appeared at that site there was no pocito, or church, but only earth. Some devotees believe that the apparition image was

the small crucifix now in the pocito room and not the Christ of Esquipulas behind the altar.

A high demand for holy dirt has also jeopardized structures at other devotional sites. In Mexico, during a government assault on the Catholic Church after 1926, soldiers broke into the church in Otatitlán and stole the Black Christ there. They took the statue to the banks of the Papaloapan River and tried to burn it but, that failing, sawed off its head. In folk belief the earth was infused with Christ’s blood and power where the statue was decapitated. The site of this abduction and murder, as devotees describe the profanation, was later marked by a tomb-like monument. On feast days multitudes of pilgrims collect this sacred dirt for curative purposes, as pilgrims do at Chimayó, and eventually the monument was undermined to near collapse. A cement slab was added to protect the monument from falling, and now the digging continues as close as possible to the spilled blood, at the edge of the slab and sometimes beneath it.

Visitors to Chimayó also ask if the pocito dirt replenishes itself miraculously, as is commonly believed. “I tell them,” Father Julio said, “that God has better things to do than have the pocito filled with dirt.” He then explained that the santuario staff—“in front of people, we don’t hide it from them”— fills the pocito as needed, which is quite often, with dirt from a nearby hillside. He blesses this trucked-in dirt, in the same way that a priest would bless the water that becomes holy water. But the dirt is already blessed, Father Julio said, because it is taken from this same region and from the same earth in which the Christ of Esquipulas was discovered. Pat held a related view: “I think all of the dirt in this area is sacred. I look for the presence of God in everything, so it’s not in the dirt in a little hole, it’s in the dirt here all around us.” Pat then told the story of a man from Colorado who delivered hay to her ranch. “I wish I had time to go to the santuario and get some dirt,” the man said, and Pat replied, “Let me give you some dirt from here.”

Leroy had a similar story. I didn’t understand it well on the first narration, so I returned later to ask him what he meant. “Holy water is blessed by a priest,” he said, “but in fact water came to be because God provided it, so the water that runs in the river and the water that we get from our well—it’s all holy water. And that’s what I meant.” He then reiterated that some visitors to Chimayó “came by while we were having dinner and they knocked at the door. They wanted to find out if we had the keys to the church because that’s what the custom was in the past.” Access is now controlled by the parish, and Leroy told the family he didn’t have keys. “They said, ‘If we can’t get in the church, we’d at least like to get holy dirt.’ I told them, ‘You’re welcome to get dirt from outside’ and they wondered what my thoughts were. And

I said, ‘Well, the priest and I in the past have made trips to an area where the land is not worked, or just virgin land that’s out there, and he would bless it and I would load it in my pickup and deliver it to the pocito. So in fact, my thoughts are all the land is holy. So you’re welcome to get some land and take it with you—it’s from this area.’ And they were satisfied with that; they did take some and they left.”

The idea that all earth is sacred acquires new meanings and is ritualized during the hundred-mile Pilgrimages for Vocations made annually in June. En route from cardinal points in the state the pilgrims gather dirt at the villages and Indian pueblos through which they pass, and sometimes at penitente moradas. The pilgrims refer to all of this earth as sacred dirt or sacred soil. When I asked Gabriel why, he said, “It’s our earth, for one, and every town has their blood, sweat, and tears on their soil,” so that the people and their history are in some sense present in their land. For Adriano, the dirt was especially sacred because it was taken from churchyards. He had noticed during a recent pilgrimage, his first, that “in the small towns the church is in the center of town,” and he explained that this was “because their life was based on religion, their faith in God. That was the center of everybody’s life.” Dirt from these places at the center is collected by locals and given to pilgrims during gatherings known as encuentros. A bag that gradually fills with the dirt from these various sites is carried on each of the pilgrim routes, which then converge at the santuario.

Shortly after arrival of these pilgrimages there is a service at the santuario’s outdoor mass area. The leader of each pilgrim group presents the dirt to the archbishop while reciting a prayer that includes, “Accept this sacred soil as a symbol of the unity of the people of God.” As each bag is presented, the archbishop empties the dirt on the ground to form a circle, with a cross on top of it. This intermingling symbolizes the unification of peoples and cultures represented by dirt brought in pilgrimage from their lands. Father Ed, the spiritual director of the pilgrimages, described the dirt as the soul of the communities through which the pilgrims passed. Another pilgrim, Daniel, referred to the ritual as representative of “the mixture of the cultures, to bring them all together, to unite them as one”; and Adriano said that the ritual of intermingling is “bringing everybody together from that place where the dirt was taken. So if it was from the church in Questa, once it was blessed in Chimayó by the archbishop, then everybody in Questa was blessed.”

The miraculous attributes of the dirt at Chimayó preceded the santuario and contributed to permission for its construction. In 1813, the pastor of Santa Cruz de la Cañada parish, which included Chimayó, supported Bernardo Abeyta’s petition to build a chapel. The pastor, Fray Sebastián Álvarez, wrote

to the Bishop of Durango (who had jurisdiction over Mexico’s northern frontier) that Chimayó “is frequented by many people” who come from great distances “to experience relief and healing of their ailments.” The source of the curative power was ambiguously attributed to the dirt and what Fray Sebastián’s called “the miraculous image of the Lord of Esquipulas,” which was venerated in Abeyta’s private chapel for the years prior to construction of the santuario. Sometime thereafter, as Father Julio explained, “People began to relate the healing not to the crucifix, but rather to the earth, to the earth where the crucifix had been.”

In the United States the use of holy dirt for healing might seem unique, but such use has many antecedents in Spanish America and especially in Mexico. (White and red dirt are eaten—a practice known as geophagy—for nonreligious reasons in the American South.) At the Esquipulas shrine in Guatemala, the miraculous dirt is sometimes processed into tablets or small cakes stamped in relief with an image of Christ, the Virgin, or a saint. The earth is mined at a cave near the shrine, then pounded, sifted through a fine sieve, moistened, rolled into coils, sliced, stamped, sun dried, and packaged. Technically the substance is not dirt but rather a naturally occurring white, soft, chalky, claylike rock called kaolin. A very similar white earth was used for tablets stamped with the likeness of the Virgen de San Juan de Los Lagos in Jalisco, Mexico, and blessed by contact with this miraculous image. Elsewhere, in Mexico state, unprocessed white earth is eaten at the shrine in Chalma. In Oaxaca, at a shrine of the Virgen de Juquila, petitionary offerings are made with the clay dirt there and some devotees take dirt home for curative and other purposes, or make signs of the cross on their foreheads.

The dirt in Chimayó is unprocessed, with the exception of screening when necessary and blessing. In 1929 a Santa Fe Transportation Company bulletin recommended a stop at Chimayó to acquire some holy dirt. “The usual method employed to obtain the benefit desired was to take a small amount of the earth and make of it a sort of tea, or drink. Those who came from a distance usually took back with them a small quantity of the earth as a safe-guard against possible illness in the future.” A few years later a WPA report explained that “the earth is dissolved in water for internal use or converted into a mud wash which is applied to the body,” which are the most prominent uses today, together with a dry rub. Some people add a pinch to boost the potency of medicines. The report also quoted a 1915 study: “The custom was, when a storm became fierce, to throw a few grains of earth into the blazing fire and when the smoke reached the top of the chimney the fury of the elements abated, and if there was lightning, its magic influence

changed its course to another direction.” Pieces of Palm Sunday fronds were likewise sent skyward through fireplaces and woodstoves for these purposes. The holy dirt was—and is—also used in fields and gardens to improve crop production.

Testimonies today report alleviation of joint and muscle pain, skin ailments, and injuries, together with beneficial effects for disease of all kinds, including cancer. Some people use the dirt to treat pets and livestock. Father Julio has met couples who were struggling with infertility and then conceived unexpectedly after visits to the santuario for other purposes. Leroy applies holy dirt for hip pain, and I asked him why the dirt has healing power. “My thinking is, the dirt is in a holy sanctuary, and while it’s there hopefully it gains some kind of communicative power that can be transferred to an individual. So for that reason I use it.”

Leroy is describing what is sometimes called a contact relic, which is to say an object or substance that has absorbed sacred power through contact with or proximity to a sacred site or miraculous image. In addition to dirt and tomb dust, contact relics often include water, flowers, and, in previous centuries, lamp oil, all of which give intangible sacred power a material medium. In Chimayó, as elsewhere in Spanish America, pilgrims and others acquire contact relics because they make sacred power tangible, portable, and transferrable, so that the benefits can continue far from the shrine and long after the visit. Many visitors, particularly tourists, acquire dirt and other contact relics simply as souvenirs.

The renown of dirt with curative properties is conducive to placebo effects, belief in magical cures, and even scams. In 1992 an enterprising Los Angeles mail-order operation sold a small “miracle cross” featuring a center bubble filled with Chimayó dirt. Ads in supermarket tabloids promised “you will be blessed with love, luck, and financial security” and “your money problems will fade as your savings grow.” A full-page ad in the National Examiner in April 1992 assured that for $18.95 (plus $1 shipping) “the Miracle Cross of Chimayó will immediately and permanently change your life for the better or you may return it for a full, complete refund—at any time! No questions asked.” The santuario asked some questions and sale of the miracle cross was discontinued.

Recent pastors at Chimayó, first Father Roca and now Father Julio, have made it clear that the dirt in itself has no curative power. Beliefs nevertheless persist. Ruben, who was once an altar boy and is now a Protestant, had a clearer understanding that the santuario priests and many informed Catholics would share. “The dirt has no healing power,” Ruben said. “The healing power comes from God and your faith.” Angelo developed this idea.

“It’s not a magic potion. It’s going to heal you because you believe in the power of God, not the power of the dirt.”

Angelo then added a comment that rescued something of the dirt’s utility and helped to explain the high demand. “The dirt is the vehicle. It’s not the actual grace, it’s the vehicle to the grace. But I think the dirt is important. Because as humans sometimes we just need that tangible substance [he gestures as though rubbing dirt on his forearm] to say, ‘This is God’s blessing on me.’ ” Along these lines a text posted at the santuario explains that the holy dirt is “a kind of sacramental sign, in the same manner that holy water or ashes for Ash Wednesday are effective signs of God’s grace.”

A flyer in the pocito room guides visitors to address their petitions to God with fervent faith and prayer rather than expecting that holy dirt alone will solve their problems.

Proliferation of holy-dirt miracles depends largely on what constitutes a miracle, and what variables (medical interventions, emotions, expectations, cognitive bias) are recognized as contributing causes of an effect. Everyday miracles are not events in themselves but rather are religious interpretations of events. In most medical miracles nothing is seen but an improvement of health that likely had multiple causes, sometimes including surgery and chemotherapy. The events regarded as holy-dirt miracles are unlikely to meet the Congregation of Rites’ standard of a complete, permanent, and instantaneous cure or the Congregation for the Causes of Saints’ current criterion of scientifically inexplicable complete recovery.

The attribution of miracles in the broader sense—the miracles of everyday life—requires a certain flexibility and willingness to acknowledge lower-order blessings. A miracle concerning cancer might entail not full remission but rather alleviation of suffering, positive emotions conducive to convalescence, reinforcement of the will to live, and unexpected years of healthy life. One of the santuario’s most celebrated miracles is precisely in this lower-order register. George had lost his central vision and eighty percent of his peripheral vision at the age of fifteen. In 1974, when he was nineteen, he hitchhiked to Chimayó in a state of desperation after a friend was killed in a motorcycle accident. Near the end of his visit, while sitting in the first pew and looking up at the Christ of Esquipulas, George had a vision that jump-started his motivation, changed his life, and contributed to his many and diverse successes, notably as a world-class runner, an author, and an artist.

But George remained nearly blind. “I didn’t get my sight back, but I got my will to live back,” George said later. “To me that’s a miracle.” In an interview he added, “It didn’t heal me physically, but I don’t think we should look for physical healings all the time.” When asked what advice he would give to