The Sun and Its Shade Piper Cj

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-sun-and-its-shade-piper-cj-2/

ebookmass.com

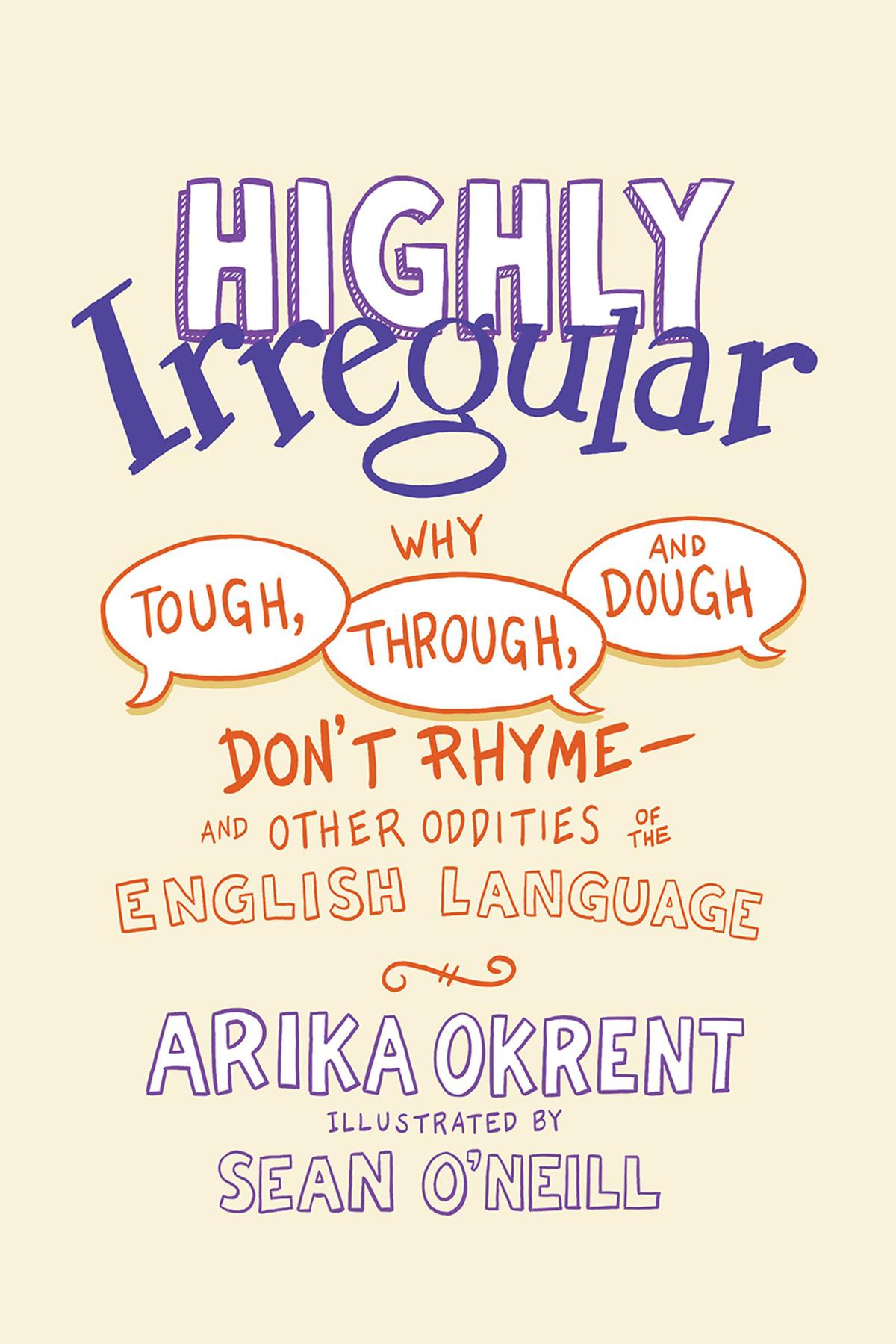

Highly Irregular

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

© Arika Okrent 2021

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Okrent, Arika, author. Title: Highly irregular : why tough, through, and dough don’t rhyme—and other oddities of the English language / Arika Okrent ; Illustrations by Sean O’Neill. Description: New York : Oxford University Press, 2021. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021004585 (print) | LCCN 2021004586 (ebook) | ISBN 9780197539408 (hardback) | ISBN 9780197539422 (epub) Subjects: LCSH: English language—Orthography and spelling—History. | English language—Pronunciation.

Classification: LCC PE1141 .O35 2021 (print) | LCC PE1141 (ebook) | DDC 421/.52—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021004585

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021004586

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780197539408.001.0001

Table of Contents

What the Hell, English?

The Colonel of Truth: What Is the Deal with the Word Colonel?

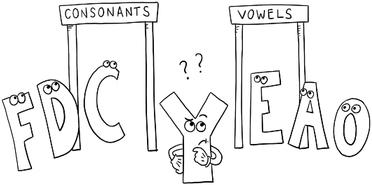

Fairweather Vowels: Why Is Ya Sometimes Vowel?

Hey Large Spender: Why Do We Order a LargeDrink and Not a BigOne?

Crazy English: Why Do We Drive on a Parkway and Park on a Driveway?

What the Hell Is with WhattheHell?

Blame the Barbarians

Thoroughly Tough, Right? Why Don’t Tough, Through, and DoughRhyme?

Getting and Giving the General Gist: Why Are There Two Ways to Say the Letter G?

Egging Them On: What Is the EggDoing in EggOn?

I Eated All the Cookies: Why Do We Have Irregular Verbs?

It Goes By So Fastly: Why Do We Move Slowly but Not Fastly? And Step Softly but Not Hardly?

Elegantly Clad and Stylishly Shod: Why Is It Clean-Shaven and Not Clean-Shaved?

Six of One, Half a Twoteen of the Other: Why Is It Eleven, TwelveInstead of Oneteen,Twoteen?

Woe Is We: Why Is It WoeIsMe, Not IAmWoe?

Blame the French

A Sizeable, Substantial, Extensive Vocabulary: Why Are There So Many Synonyms?

Don’t InSULT Me with That INsult: Are There Noun-Verb Pairs That Only Differ by Stress?

Without Fail: Why Is It WithoutFailand Not Failureor Failing?

Ask the Poets Laureate: Why Is It SumTotaland Not Total Sum?

Of Unrequited Lof: Why Isn’t OfSpelled with a V?

Blame the Printing Press

Uninvited Ghuests: Why Are Ghost, Ghastly, and Ghoul Spelled with Gh?

Gnat, Knot, Comb, Wrist: Why Do We Have Silent Consonants?

Coulda, Shoulda, Woulda: Why Is There a Silent L?

Peek, Peak, Piece, People: Why Are There So Many Ways to Write the ‘Ee’ Sound?

Crew, Grew, Stew, New . . . Sew?: Why Don’t Sewand NewRhyme?

Blame the Snobs

Get Receipts on Those Extra Letters: Why Is There a Pin Receipt, an Lin Salmon, and a Bin Doubt?

Asthma, Phlegm, and Diarrhea: Why All the Extra Letters?

The Data Are In on the Octopi: What’s the Deal with Latin Plurals?

Too Much Discretion: Keeping Discreetand Discrete Discrete, Discreetly

Pick a Color/Colour: Can’t We Get This Standardized/Standardised?

Blame Ourselves

Couth, Kempt, and Ruthful: Why Have Some Words Lost Their Better Halves?

If It Ain’t Broke, Don’t Scramble It: Why Is There No Egg in Eggplant?

Proving the Rule: How Can an Exception Prove a Rule?

How Dare You Say “How Try You”!: Why DareIsn’t Like the Other Verbs

Release the Meese: Why Isn’t the Plural of MooseMeese?

Why Do Noses Run and Feet Smell?: A Corny Joke with a Serious Answer

Negative Fixation: Why Can You Say “This Won’t Take Long” but Not “This Will Take Long”?

Abbreviation Deflation: Why Is There an Rin Mrs.?

How It Comes to Be: How Come We Say HowCome?

Phrasal Verbs—Let’s Go Over Them: But Don’t Try to “Go Them Over” (You Can Look Them Over Though)

Terrible and Terrific, Awful and Awesome: How Does the Same Root Get Opposite Meanings?

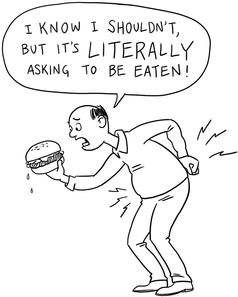

Literally Messed Up: How Did LiterallyGet to Mean Figuratively?

That’s Enough Now, English

Acknowledgments

Notes

Bibliography

Index

What the Hell, English?

Dearest creature in creation

Studying English pronunciation, I will teach you in my verse Sounds like corpse, corps, horse and worse. I will keep you, Susy, busy, Make your head with heat grow dizzy; Tear in eye, your dress you’ll tear; Queer, fair seer, hear my prayer Pray, console your loving poet, Make my coat look new, dear, sew it!

Just compare heart, hear and heard, Dies and diet, lord and word.

So begins the poem “The Chaos,” which the Simplified Spelling Society called “an indictment of the chaos of English spelling,” or, more flamboyantly, a “compendium of cacography.” It was printed in the society’s summer newsletter in 1986 and went on for 246 lines. It came with a specific request: “Can any reader name the author or supply any further details about the poem?”

Before landing with the editor of the newsletter, the poem had passed through many hands. It was rumored to have been discovered in a girls’ high school in Germany at the end of World War II. Retyped and mimeographed copies of slightly different versions had made their way around Europe. There were stories from students of English in various countries who recalled their professors using it in class to broach, in a lighthearted way, the frustrating challenge of figuring out how to match sound and spelling in the language.

The origin of the poem was eventually tracked down, and in 1994 the Simplified Spelling Society issued an update. The author was a Dutch writer named Gerard Nolst Trenité. The poem was first published in 1920 in an appendix to the fourth edition of his book Drop Your Foreign Accent: engelsche uitspraakoefeningen. The Dutch subtitle translates to “a guide to English pronunciation,” but Nolst Trenité clarified that it was “not a guide” but “an exercise book . . . less like a drill-master, who teaches you how to perform your feats, than like a set of gymnastic apparatus on which you have to perform them yourself—vocal gymnastics.”

The main apparatus was verse, in which “rhythm and rhyme may act as fly-wheels, strengthening and equalizing the movement of the vocal organs.” The poems he supplied were easy to commit to memory, and, he suggested, “Having chosen those which contain your special stumblingblocks, you may conveniently practice them during a lonely walk, sitting all by yourself in a railway carriage, etc.”

He should know. After all, he had had to do the work to learn to produce it himself. Born in Utrecht in 1870, he learned English (among other languages) the hard way, at school. After university, he spent two years in San Francisco,

where he worked as a tutor for the children of a Dutch family. But otherwise, aside from a short stint teaching English and French in the Dutch East Indies, he spent the rest of his life in the Netherlands, in Haarlem, at the same address.

Most of Nolst Trenité’s career was spent not in explaining the challenging intricacies of English but in nitpicking defense of his own native language. For more than thirty years he had a column in the GroeneAmsterdammerwhere, writing under the name Charivarius, he scolded, berated, teased, and criticized his fellow countrymen for their sloppy and annoying language habits.

Charivarius had a long list of favorite annoyances: too much capitalization in titles; the overuse of the word nauwelijks (hardly); Germanisms, such as the use of slagroom for whipped cream instead of the pure Dutch geklopteroom. He railed against pleonasms like “fierce fire” (fire is already fierce!) and “useless waste” (waste is already understood to be useless!) and came up with his own labels for his favorite peeves. Fnaffersand fnuiterswere those who used vanaf and vanuit (from off, from out) for what he decreed should be simply van(from).

Many of these “errors” are fully accepted in Dutch now, and some of them may have only ever bothered Charivarius

to begin with.

Drop Your Foreign Accent went through seven editions during Nolst Trenité’s lifetime (and four more after his 1946 death). “The Chaos” nearly doubled in length over that time, as Nolst Trenité thought of more and more English spelling inconsistencies to add to it. As the poem grew, so did the force of its comic absurdity. In one book of his collected verses, he introduced it with the line “May it spread fear and dismay.”

The final lines of the poem itself read:

Finally: which rhymes with enough, Though, through,plough, cough, hough, or tough? Hiccoughhas the sound of ‘sup’ . . . My advice is—give it up!

But of course he didn’t really want the reader to give up on English. He ends the introduction to Drop Your Foreign Accent with a notification that the appendix includes a “small collection of phonetical paradoxes” in verse form and that “the last line contains an advice; my advice is—don’t take it.”

Nolst Trenité saw that the Dutch language had its own inconsistencies too. One poem called “Taal-Rijm” (Language rhyme) was “dedicated to the foreigner who learns Dutch.” He points out, for example, that while the plural of bal(ball) is ballen, the plural of dal(valley) is not dallen. Collected all together, these types of irregularities do not reach nearly the same level of absurdity or of inspiring “fear and dismay” as those in “The Chaos.” After all, they are common in many other languages, including English (the plural of box is not boxen).

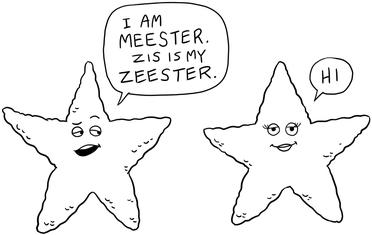

It is notable that when he tries to incorporate some of the type of spelling irregularities of his English hit into his poem on Dutch, it’s a really effortful stretch. He comes up with only one or two place names (the city of Gorinchem is pronounced ‘gorkum’) and the pair meester (starfish) and

zeester (sister), which don’t quite fully rhyme, but only because they have slightly different stress patterns. While “The Chaos” ends with full-throated ironic drama (“My advice is—give it up!”) “Taal-Rijm” peters out with a gentle shrug: “Dutch is not so easy either.”

Nolst Trenité could not make anything comparable to “The Chaos” for Dutch because Dutch doesn’t have anything like the English spelling problem. No other European language does. French has its share of silent letters and alternate ways of spelling the same sound, but it is far more systematic. All languages have their infelicities and awkward bits, but English has its own special kind of weirdness. It can be hard to see from the inside. English speakers are well aware of the oddness of spellings like colonel or hors d’oeuvres, but it takes an outsider like a foreigner trying to learn the language or a Nolst Trenité trying to teach it to see that sewand newshould rhyme but don’t.

Not only did Nolst Trenité have an outsider’s perspective, but he had the language pedant’s perspective. His complaints about the way his fellow citizens butchered the Dutch language were different from his complaints about

English, but they came from the same expectation that language should be a logical, orderly system.

This is an expectation which most of us share to a degree. It’s why we find a poem like “The Chaos” funny. It says, “Behold the utter lack of systematicity in this system!” If we didn’t think there was supposed to be a system, the joke would be meaningless. And we know, implicitly, that there is a system, despite all the messy exceptions. That is why, if we come across an unfamiliar word like frew, we will not be overcome with confusion and uncertainty, but simply rhyme it with new. It’s why we can come up with a spelling to make ourselves understood, even if we get it wrong, as children often do. There are patterns and regularities to exploit. Those patterns and regularities are rules.

However, the patterns are often overshadowed by what looks like randomness, and there are irregularities everywhere, not just in the spelling system. At every level of language, from spelling to vocabulary to grammar to word order to meaning, there are violations of harmony and order. These violations might be more obvious to non-English speakers trying to learn it, but if English is your native language, you are still often forced to confront them. A colleague who has learned English as a second language asks you why it’s wrong to say “Let’s go them over” when “Let’s look them over” is fine, and you find yourself sinking in logical quicksand as you try to come up with an answer. A child asks you why there’s an l in could, and you throw up your hands and say, “English is just weird.” But it’s not the case that English is justweird. It’s weird in specific ways for specific reasons. It’s not utterly unexplainable chaos. It’s just highly irregular.

Highly Irregular can be read in two different, complementary ways. It is a collection of answers to questions about English, some familiar (How does an exception prove a rule? Why do noses run and feet smell?) and some that may never have occurred to you before (How

come we say how come? Why isn’t of spelled with a v?). These can be casually browsed in any order.

At the same time, if read from start to finish, it will present a deeper story, a history of English that explores the tension between logic and habit in language development. Language is always being pulled in two directions. It is infinitely generative, allowing us to draw from a limited set of units, sounds, words, idioms, and phrases to create sentences that have never been spoken before, meanings that have never been expressed before, texts that have never been written before. It is also conservative, a cultural tradition that we pass from person to person, embedded in everyday habits that are reinforced by social pressure, institutional customs, and constant repetition.

In most cases, the explanation for why things are the way they are is a story about the way they were and why people either changed them or kept them frozen while the world changed around them. The individual articles are organized into five sections, and if you read just the introduction to each of these sections, you get a nice, compact history of English.

Before diving into that history, we’ll take a brief tour of the type of weirdness this book is about. When I told people I was writing about the weirdness of English, the places where it didn’t seem to conform to a system or even to logic, they often had suggestions for questions I could address, such as “Why do people confuse loose and lose?” or “Why do some people say ‘This needs washed’?” The assumption was that the place to look for unsystematic or illogical English was in mistakes or deviations from the correct standard.

But one doesn’t need to turn to nonstandard English to find the flaws, as anyone who has studied English as a foreign language can tell you. The types of questions I will deal with here are part of fully accepted, unquestionably correct, standard English. The language is shot through with

absurdity, and I will begin in this section with a selection of questions that illustrate how the weirdness permeates all levels, from pronunciation and spelling (Why is y a “sometimes” vowel? What is the deal with the word colonel?) to word meaning and sentence structure (Why do we order a large drink and not a bigone? Why do we drive on a parkway and park on a driveway? What the hell is with Whatthehell?).

Then we move on to the (good-natured! jocular!) question of who is to blame for this mess. First, we can blame the barbarians (section 2), who gave us the old, fossil layers of the language that continue to make the surface bumpy. Then, we can blame the French (section 3) for centuries of linguistic rule, but only in some areas and not others, fracturing our vocabulary and writing system. Then we can blame the printing press (section 4) for ironing in weird wrinkles that might have otherwise smoothed themselves out. And then we can blame the snobs (section 5) for topdown decisions made from inconsistent personal gripes. Though these sections are arranged in general historical order, the boundaries from one era to the next are porous. Answers are assigned to one section, even when they result from the accumulation of many types of blame. And the final section, “Blame Ourselves” (section 6), describes not the final stage of the history of English but one that has been there all along. Everything that happens to language happens because of us humans and the way we are.

No engineer would purposefully design a language to be this disorderly. But language is not the product of engineering. It is the product of evolution, and the faults of English are similar to those that can be found in our bodies. Why do we have an appendix? Why are we so prone to back pain? Why do we love unhealthy food? Some biological adaptations help us at one point but hurt us later. Some changes stick around for no reason at all. The process of evolution does not itself have a goal, but it makes us what

we are. Some strengths become weaknesses; some useful parts become useless.

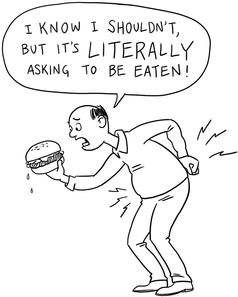

The ghin English spelling is like our appendix. It used to have a function but now dangles there mutely, except when it flares up to cause problems for people learning to spell. Irregular verbs are our lower back pain, a product of adjusting an old skeletal structure to a new way of getting around. Figurative literally is a big, juicy cheeseburger, so tempting even when we know the experts are telling us it’s no good.

Despite the parallels, when it comes to language, the evolution metaphor can only go so far. In the past thousand years, our bodies have hardly changed at all, while our languages have become unrecognizable. Language is a social institution, and the path it takes is determined not by the transmission of genes from one generation to the next but by the transmission of utterances from one person to the next. We have a role, both as individuals and as groups, in determining what language will do. And yet, try as we might, we can’t willfully control it. We make the rules, but not by actively deciding what they should be. If we did, they’d be a lot less messy.

The Colonel of Truth

What Is the Deal with the Word Colonel?

One of the worst offenders in a crowded field of unbelievable English spellings is colonel, pronounced ‘kernel.’ Where do we get that ‘r’ sound from? Why are there silent ‘o’s? What the heck is going on with this word? How can it be so shamelessly nonsensical?

There’s plenty of blame to go around for this one, but it starts with the French. They borrowed the word from the Italians, making a bit of a change in the process, and we borrowed it from the French. Much of the English vocabulary of warfare comes to us this way, from Italian through French —words like cavalry, infantry, citadel, battalion, brigade, corporal, and also colonel. When one language borrows from another, the words get adapted to fit the new language. Italian cavalleria became French cavalerie became English calvary. Infanteriabecame infanteriebecame infantry.

But when the French borrowed colonnello from the Italians, they changed it to coronel.

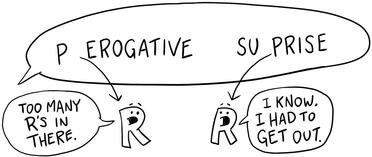

Why did they do that? It wasn’t just a random mistake. It came through a very common process called dissimilation. When two instances of the same sound occur close to each other in a word, people tend to change one of the instances to something else or drop it altogether. Think of the words prerogative or surprise. Most of the time English speakers pronounce these without the first r.

The ‘l’ and ‘r’ sounds are frequent players in the dissimilation game, whether by switching places or dropping out. Because of this, Latin developed two endings to make a noun into an adjective, -alisor -aris, depending on whether there were other ‘l’s close by in the root. From vita(life), we get vit-alis (vital), “pertaining to life.” From tempus (time), we get tempor-alis(temporal), “pertaining to time.” But the adjectives from populus(the people) and regula(rule) were popul-aris and regul-aris. Populalis and regulalis were just too l-ful for Latin.

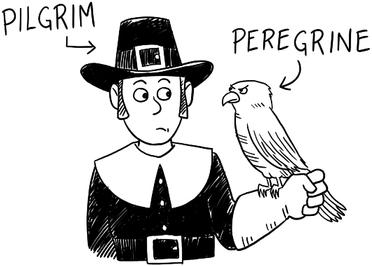

Some words were just too r-ful for other languages. The classical Latin word peregrinus(pilgrim) became pelegrinus in late Latin and then pellegrino in Italian and pelerin in French, and this version with the lis what we based pilgrim on. When we speak of the peregrine falcon, however, we go with the classical peregrinus-based form. It’s not that people can’t say words with too many r’s or l’s too close to each other; it’s just very common and unsurprising for languages to switch things up in these cases.

Other r-to-lswitches resulted in English purpleand marble (from pupure and marbre). Arbor and miraculum became arboland milagroin Spanish. It happens.

Which is to say the French recasting of colonnello as coronel is totally normal and no big deal. We borrowed it with the coronel spelling and three-syllable pronunciation (‘co-ro-nel’) in the mid-1500s, but over time the pronunciation got reduced to ‘kernel.’ This is also pretty normal and expected. Whole syllables have disappeared from words like chocolate (‘choklit’), vegetable (‘vegtible’), favorite(‘favrit’), and many others.

What’s not normal and expected is the way we ended up with the spelling colonel. In the late sixteenth century scholars started producing English translations of Italian military treatises. Under the influence of the originals, where they kept seeing colonnello, scholarly types started spelling it colonel instead of coronel. This version had the shine of the more literary, etymologically correct choice. The French, also reading these Italian works, started writing colonel as well.

After some back and forth, by 1650 the spelling had standardized to the l version. But the French, who had introduced the whole r version in the first place, adjusted

their pronunciation to the new spelling and said ‘co-lo-nel.’ And while many English speakers also pronounced it with the l, enough people just kept on pronouncing it the ‘kernel’ way. In the 1700s pronouncing dictionaries listed the colonel spelling with the ‘kernel’ pronunciation.

The ultimate resolution, Italian-style lspelling with Frenchstyle r pronunciation (which the French no longer themselves used), did not go unremarked upon for its absurdity. It became a popular nineteenth-century joke, in limericks such as this:

There was a brave soldier, a Colonel, Who swore in a way most infolonel; But he never once thought As a Christian man ought He imperiled his own life etolonel.

Colonelsnuck in through successive waves of borrowing and the establishment of habits that became hard to break. The early French version spread the pronunciation; the later Italian-inspired version spread the spelling among a certain class of people—those who do a lot of writing and so spread the standards for writing (see “Blame the Snobs”). But it’s harder to change how things are spoken. Spoken ‘col’nel’ made an appearance, but simply couldn’t catch on.

And so we’re left with the ridiculous contradiction of colonel. So ridiculous it’s become almost a point of pride. Colonel can be ‘kernel’ if we say so. That’s the stubborn defiance of English.

Fairweather Vowels

Why Is Ya Sometimes Vowel?

First we learn to speak, then we learn to write. Somewhere in between, we learn to recite the alphabet. We train it into our consciousness through repetition, memorization, and a special song. Once we’ve got the alphabet down, we learn about an important subset of the alphabet, the vowels, and it has its own memorization routine to go with it—a chant that goes like this: a, e, i, o, u. . . and sometimes y. Sometimes? There were none of these provisional “sometimes” members in the alphabet song. The letters all seemed to know they were letters. Why is yso unsure if it’s a vowel or a consonant? Can’t it just decide what it is? Why is ya “sometimes” vowel?

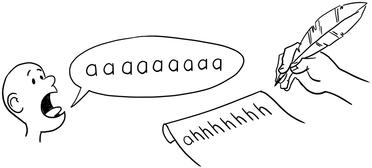

Understanding the why of yinvolves a very important and often overlooked fact. Writing is not the same thing as speech.

If I ask you what letter a word starts with, you know that I am asking about the written form of the word, not the spoken form. If I ask “What letter does psychology start with” the answer is p, even though, as spoken, it starts with an ‘s’ sound.

If I ask you “What vowel does aunt start with” there are two ways to answer, depending on whether we’re talking about the written form or the spoken. For the written form the answer is simple: a. For the spoken form, it’s complicated: “an ‘a’ sound like in cat” or “an ‘ah’ sound like in father” or “an ‘aw’ sound like in saw.” Vowel can mean two different things, a written symbol or a sound.

It’s difficult to write about spoken vowels in a clear and precise way. I have no idea what dialect you, the reader, speak or how you actually pronounce cat, father, or saw. Linguists use special symbols from something called the International Phonetic Alphabet when discussing specific sounds. The three vowel sounds in aunt mentioned above would be /æ/, /ɑ/, and /ɔ/. Unfortunately, most people don’t learn to use that alphabet, so we have to resort to approximations like ‘aw’ or descriptions like “as in saw.” Our regular alphabet is not built to handle the sounds of English very well.

While we casually refer to letters, which are written symbols, as vowels or consonants, the concepts of vowel and consonant properly belong to the domain of speech. In general terms, a consonant is a speech sound formed by some kind of constriction or impeding of air flow through the vocal tract, and a vowel lets the air flow freely through.

In English, we have twenty-one written letters (if you count y) that we call consonants. But if we’re talking about speech, there are twenty-five or so. How does that work? Well, some consonants don’t get their own letters. ‘Sh’ is a single consonant sound. We just reuse two other letters in order to spell it.

There are twelve or sixteen or maybe even twenty vowels in English, depending on your dialect. There’s aas in cator father, e as in be or bed, i as in sir or big, o as in soap or look, and uas in sumor true. We haven’t even gotten to the vowel sounds in houseor timeor say. And if you come from New York or Scotland or Texas, these descriptions will work differently for you.

So as mentioned before, if, when it comes to spoken language, consonants constrict while vowels let the air flow freely through, then what kind of sound does yrepresent? It can stand for either type. In yes, y is representing a consonant, and in gymit is representing a vowel.

In fact, due to the imperfect match between writing and speech, there are other “sometimes” vowels: w is a consonant in we and part of a diphthong vowel in now. His a consonant in hat, but what is it in ah? It’s part of the representation of a different vowel sound; compare the phrase amanwith ah,man. If we look hard enough, we can even find examples of “sometimes” consonants. What

sound does the o represent in one? What sound does the u represent in united? They are consonant + vowel combinations ‘wuh’ and ‘yu.’

We don’t bother to add the “sometimes” clause for letters other than y because in practical terms y is the only one that really needs that qualification. It’s the one that swings between vowel and consonant the most. It represents a consonant in common words like you, year, yet, and beyond. It represents a vowel at the end of all kinds of words (my, by, fly, merry, curry, study) and suffixes that attach to words (lemon-y, understanding-ly). But the reason we probably learn the “sometimes” clause when we learn to read is because yalso represents a vowel in the middleof a bunch of words that have etymological origins in Greek (syllable, system, cycle, type, hyper, lyrics, gym). That’s a position where in the rest of the language we’d usually find an a, e, i, o, or u. They are spelled that way because they had the Greek letter ypsilon in that position.

A, e, i, o, u, and sometimes y is not a bad rule of thumb. Most of the time a spoken vowel will be represented by one of those written forms. But it’s worth remembering that letters are not speech sounds. They are lines on a page that nudge us, quite imperfectly, toward the sounds of the things we say.