Introduction

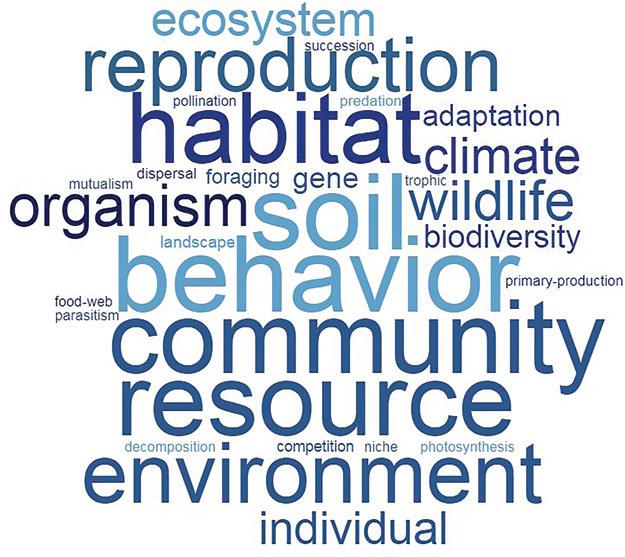

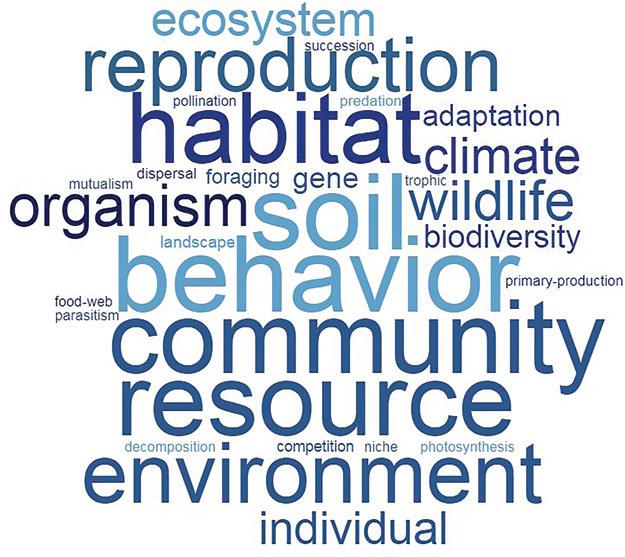

Habitat is where an organism lives—that’s the simplest definition. However, as a concept integral to many areas of ecological investigation and knowledge, habitat is a bit more complicated and comprehensive than simply where an organism lives. I accessed the immense ISI Web of Science literature database and did a keyword search on “habitat” and several other terms often used by ecologists. Of course in return I received many results—more papers than I could read in several lifetimes and a list of titles that would take several days or longer to go through, never mind reading the abstracts. My point: for ecologists, “habitat” is a very familiar term, concept, and real-world entity and has been for a very long time. Perhaps it could even be considered a level of ecological (if not biological) organization. As a term of common usage, it ranks right up there with several others (Fig. 1.1). Thus “habitat ecology,” broadly defined as the study of the habitat requirements of species and effects of habitat on individual survival, population persistence, and spatial distribution, has had a prominent place in the development of ecology as an academic field and as a knowledge base for conserving and managing the planet’s living natural resources.

1.1 History of the habitat concept

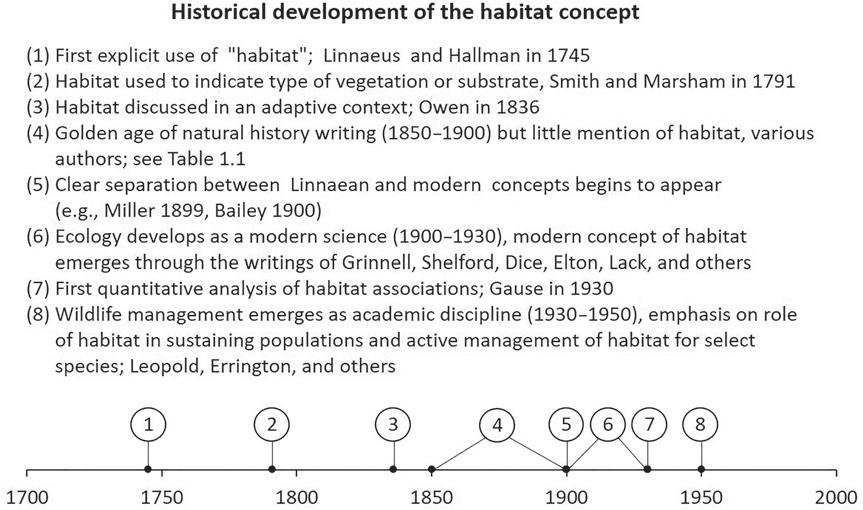

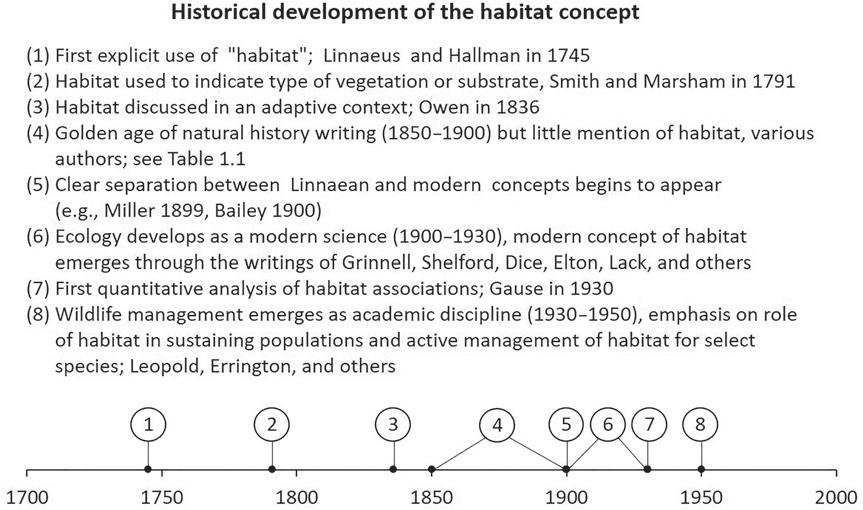

In the scientific literature, use of “habitat” predates “ecology” as the latter was not coined until 1866 by the famous German biologist and philosopher, Ernst Haeckel (Stauffer 1957). The habitat concept developed over a period of at least 200 years (Fig. 1.2). To my knowledge, no one has ever tracked down the first use of the word “habitat.” This would be a difficult task anyway given that the word has shared etymology with other similar words (e.g.,

“inhabit,” “habitant”) that have a greater realm of usage than just in biology or ecology. Carl Linnaeus used the term in 1745 in Flora Svecica as did his student, Johan Gustaf Hallman, in his dissertation in the same year, titled Dissertatio Botanica de Passiflora. By the 1766 edition of Systema Naturae, Linnaeus was routinely using “habitat” to denote the general area where a species was from, such as “Mari mediterraneo” (Mediterranean Sea) for “Testudo coriacea,” now known as the leatherback sea turtle (Dermochelys coriacea). This particular usage continued for well over 120 years and was relatively common in broad taxonomic treatises wherein each species was described in a consistent format of categories such as “appearance,” “diet,” “habits,” and “habitat.” The latter would typically be followed by only a few words indicating the geographical region (sometimes as a geopolitical label, e.g., “Mexico”) or even a single locality where the species existed and was collected. This was hardly a description of habitat in the modern sense of the word. Incidentally, the word “habits” probably dates back even further and today is somewhat archaic with regard to usage in ecological literature; it generally meant the behavior of the species.

A slightly more modern usage of “habitat” appeared by 1791. The very first volume of Transactions of the Linnean Society of London (a journal that is no longer in print) included accounts of some lichen “species” collected from southern Europe. For each species account, there was a habitat category filled with a very short descriptor in Latin such as rupibus calcareis (limestone rock), rupibus alpinis (alpine rock), ericetis alpinis (alpine moor), truncis arborum (tree trunk), and corticibus olearum (bark of olive trees) (Smith 1791). In the same volume, the habitat of the buff ermine moth (Phalaena bombyx, now

Figure 1.1 Word cloud depicting usage of “habitat” and select other terms in the ecological literature from 1864–2018. Each word was searched in ISI Web of Science along with “ecolog*” so as to eliminate papers that were not ecological. Each term appeared in the title or abstract of the following number of papers (×1,000): species—1,657, population—1,576, behavior—750, soil—749, community—728, resource—726, habitat—695, environment—592, reproduction—536, organism—415, wildlife—392, climate—352, ecosystem—333, individual—322, biodiversity—223, adaptation—210, gene—210, foraging—145, landscape—117, competition—107, dispersal—106, predation—105, photosynthesis—77, trophic—67, parasitism—52, niche—52, succession—52, primary production—51, food web—38, decomposition—38, pollination—27, and mutualism—24.

Spilarctia luteum) was listed as arboribus pomiferis and quercu (fruit-bearing trees and oaks) (Marsham 1791). These examples represent a transition to a modern concept of habitat in that the habitat of each species was viewed as the type of vegetation or substrate where the species exists rather than as the geographical location where the specimen was collected.

Another notable advancement occurred in 1836. Early in his career, the well-known naturalist and biologist, Richard Owen, prepared and presented a table of the habitats of antelope species in India and Africa during the Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London (Owen 1836). For each of 60 species, the table gave a short descriptor of the habitat, such as hilly forests, open plains, stony plains and valleys, desert borders, rocky hills, thickets, reedy banks, and Acacia groves. Of particular importance,

Owen had a specific goal for doing his habitat analysis—he wanted to test a hypothesis. He proposed that the suborbital, maxillary, and inguinal glands found in some species, but absent or underdeveloped in others, had the purpose of facilitating the aggregation of individuals of a species. That is, individual antelopes would secrete onto vegetation or large rocks and these secretions “might serve to direct individuals of the same species to each other.” Owen was looking to see whether species inhabiting open plains lacked the glands (due to the absence of shrubs and rocks to secrete on) whereas those of forest areas had the glands, and further whether gregarious species had the glands whereas solitary species did not. According to Owen, his table showed that some of the plains-inhabiting species lacked the glands and some had the glands irre-

spective of whether the species was gregarious or solitary. A similar lack of pattern was evident in the forest-dwelling species. Hence, Owen rejected his own hypothesis. In addition to testing a hypothesis, his study is notable in several other respects. He had at least a dozen or so habitat types represented among the 60 species indicating a fairly detailed classification of habitat. Owen had a specific biological and ecological reason for identifying the habitat of each species. Presumably, he compiled the table from previously published literature— perhaps an early forerunner of studies that use a macroecological approach or the comparative method, both of which involve species as the units of analysis. Lastly, Owen implicitly recognized the possibility that a physical structure on an organism might relate to the habitat where it occurs and have a specific function related to behavior. Of course, in 1836 he did not use the word “adaptation”—the development of that concept would be left to someone a couple decades later.

Interestingly, Charles Darwin did not use “habitat” in Voyage of the Beagle (1839) or On the Origin of Species (1859) although there would have been

ample opportunity to do so. Instead he used “station” and “habitation” in contexts where “habitat” could have fit, although both the former were also used in Voyage to denote a location of human settlement or occupation. In the 574 pages of The Geographical Distribution of Animals (1876), Alfred Russel Wallace used “habitat,” “habitation,” and “station” each a few times. However, he did attempt to define and distinguish “habitat” and “station” (p. 4). He defined “station” as a locality wherein two or more stations are separated by some distance but tend nonetheless to have the same habitat. In comparison with stations, habitats were recognized as having distinct vegetation or terrain. Wallace defined both terms in the context of changes in the species inhabiting each. In his words, “The whole area over which a particular animal is found may consist of any number of stations, but rarely of more than one habitat” (p. 4). With neither Darwin nor Wallace do we find a specific and detailed concept of habitat, nonetheless, Wallace’s writings began to at least hint toward the modern concept of habitat.

In the early to mid-nineteenth century, published journals devoted to natural history began to emerge.

Figure 1.2 Historical timeline for the development of the habitat concept.

Prior to this, there had been scientific journals for at least 150 years, dating back to the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society established in 1665 by the Royal Society, which itself had been organized in England only 5 years earlier. Perhaps the earliest exclusively biological journals were Transactions of the Linnean Society of London (1791) and Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London (1830), and both of these often contained natural history contributions and species accounts. During the early years, scientific studies were read to members of the societies at regular meetings—this practice continued well into the nineteenth century as represented by the famous readings of Darwin and Wallace’s theories about natural selection to members of the Linnean Society of London on July 1, 1858. Even relatively mundane papers were read at meetings, such as the previously described study by Owen presented at the meeting of the Zoological Society of London on March 22, 1836. Owen presented his hypothesis and assessment of antelope habitat as a follow-up to a paper read by Edward Bennett in which he described the facial glands of Indian antelopes. Eventually the “reading to the society members” route to publishing a scientific study became outdated. Henceforth, scientific journals could organize (perhaps under the auspices of a professional society or organization although not a necessity) without being tied to the physical process of a paper first being read at a meeting. The following journals emerged with a definite focus on natural history and in particular reporting on the discovery of new species: Annals and Magazine of Natural History (1838), Ibis (1859), American Naturalist (1867), Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History (1881), and The Auk (1884).

The time period from about 1850–1900 may have been the golden age of natural history writing. Prior to this, much of the scientific biological literature was written in Latin or in a very obtuse and longwinded way. Into the nineteenth century there were still many species to be discovered and many regions to be explored and inventoried. Professional and amateur naturalists came along and began writing in a very easy-to-read conversational type of prose. Their writings often consisted of presenting behavioral and basic ecological information on a given species often obtained by direct observation of wild

or even captive individuals. But there was either no mention of “habitat,” or habitat was denoted as a region or locality where the species or individual originated, as though following the precedent set by Linnaeus more than 100 years earlier. Many of these natural history accounts appeared in the American Naturalist between 1867 and 1880 by authors such as Elliott Coues, Augustus Fowler, Samuel Lockwood, Alpheus Packard, and Charles Abbott (see Abbott 1860, 1870a, b, c, 1873; Packard 1867, 1871, 1876; Fowler 1868a, b; Lockwood 1875, 1876). Another form of natural history writing, which might now be thought of as early taxonomy, involved a systematic treatise of a group of species in which specific characteristics of each species, sometimes including “habitat,” were presented in an orderly way. Again, habitat was conceived by these authors only in the Linnaean fashion of identifying the collecting location or geographic region where the species existed. Naturalists engaged in this type of writing typically had formal scientific training and advanced degrees and to a modern audience their papers sound more scientific than the narratives of the other type of natural history writing. These papers appeared in all the previously mentioned journals; particularly prolific writers included Edward Cope, David Jordan, Charles Abbott, Albert Günther, and Charles Cory (see Abbott 1860, 1870a, b, c, 1873; Cope 1869, 1896; Günther 1871, 1875; Jordan 1874, 1877; Jordan and Copeland 1877; Cory 1891, 1886). The authors of both types of paper often presented very comprehensive measurements and information on the morphological traits of the species with no description of habitat—again this reflects an early emphasis on taxonomy and classifying species (often by authors with close associations with museums) rather than on studying the species’ ecological role in nature. This inattention to habitat (as we conceive it from our modern perspective) was prevalent and pervasive in the period 1850–1900. Naturalists of various nationalities writing about all types of organisms in all regions of the world generally neglected to even mention the habitat of their subjects or defined the habitat in a very broad and often geographic context; that is, the Linnaean way (Table 1.1). There were occasional exceptions. Abbott (1870a) wrote about “mud-loving fishes” and even used that term

for the title of his paper. He described how a group of nine fish species (of various genera) tended to be found in very shallow and sluggish streams near Trenton, New Jersey, United States. He even mentioned that the fishes “preferred such shallow water, with the mud, to that which was deeper, to which they had access, because it was over a stony bed” (p. 387). His implicit recognition of a species having a habitat preference foreshadows a major aspect of our modern perspective of habitat—that is, that species have preferences and can actively select habitat. Even very small organisms were seen by some as having a habitat. Stokes (1888) identified the habitats of various ciliate species respectively as ponds and then went on to give a very brief description of the water and sometimes whether the ciliate species was associated with certain aquatic plants. Williamson (1894) gave a brief but very direct statement on the habitat of abalone (Haliotis sp.): “the habitat of abalone is among rocks, where, at very low tide, they may be found huddled together in a corner of a rock pool, or hedged in between fissures of immense rocks” (p. 854). In a very comprehensive species account, Wilder (1899) wrote a detailed 300-word description of the habitat of two salamander species, Desmognathus fusca and Spelerpes bilineatus: “they are found in and about running brooks that are plentifully supplied with small stones, and they seem to prefer spots shaded by trees” and “perhaps the best brooks of all are the little mountain streams that run swiftly down quite steep inclines, forming miniature cascades alternating with small shallow basins” (p. 233). Interestingly, Wilder’s habitat description is given in the context of instructing the reader on how to go about finding these secretive salamanders.

Around 1900, the definition of habitat and its use as an ecological term finally began to transition into our modern concept of habitat. A great example of this is Miller (1899). In his Mammals of New York, Gerrit Smith Miller gave a brief one-page account for each of 81 species known in the state of New York. Each account followed the same systematized format in which Miller provided information in seven different categories: synonymy, type locality, faunal position, habitat, distribution in New York, principal records, and remarks. Entries for the “habitat” category typically described the major type of vegetation or terrain where the species could be found,

such as forests, woods, woodlands, thickets, old fields, prairies, meadows, rocky hillsides, marshes, bogs, streams, and ponds, among others. Today these basic descriptors are so ingrained in both the public’s recognition of habitat and scientific parlance that we could easily and rightly say that this is a list of types of habitats. Notably, Miller’s species accounts included identification of the type locality (the place where the type specimen was collected), faunal position (a phrase Miller used to indicate a biome), and distribution in New York. So these three categories together represented the Linnaean definition of habitat (as a geographic place or region) and allowed Miller to implicitly and perhaps intentionally distinguish between that view of habitat and the emerging view of habitat as the type of vegetation, terrain, or environment where a species could be found. The latter is our modern concept of habitat in its simplest and most general form.

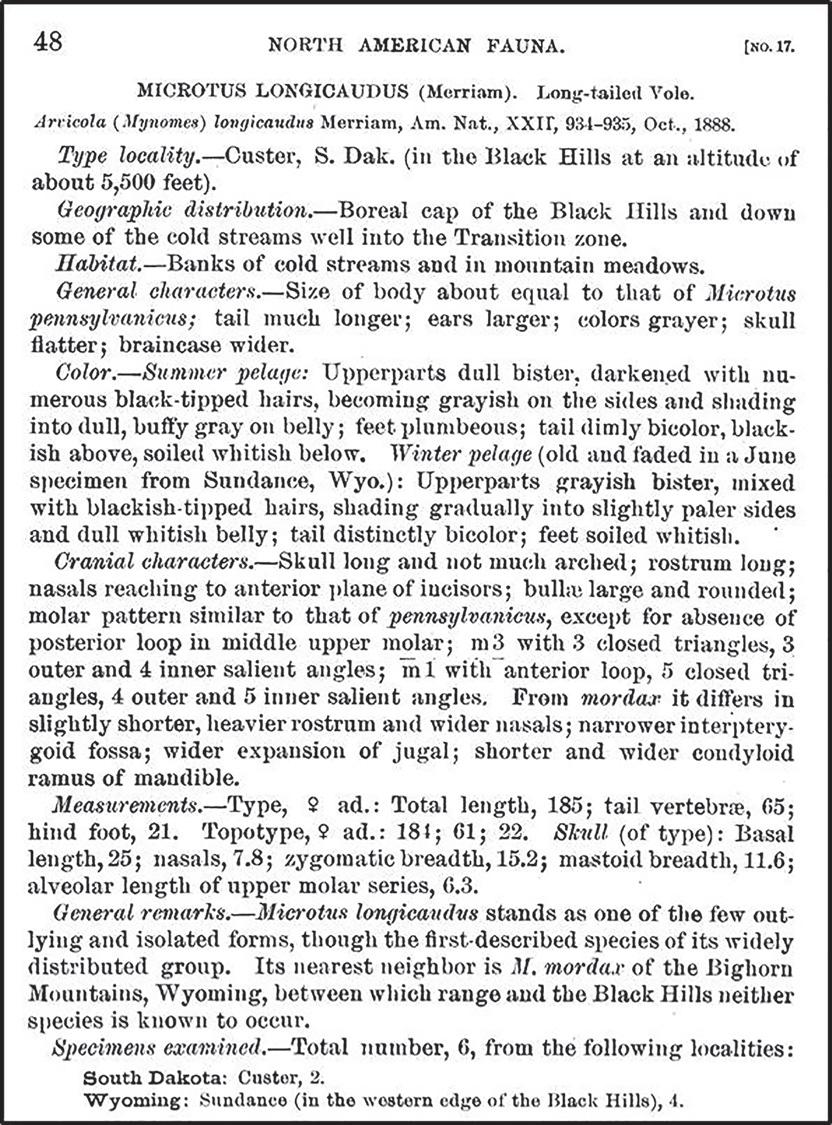

Vernon Bailey also recognized and described habitats in much the same way as Miller. In his 1900 monograph on voles (Microtus), Bailey provided a taxonomic key and extensive quantitative description of each species including measurements of particular morphological characteristics (Fig. 1.3; Bailey 1900). His monograph is thoroughly modern and scientifically detailed, more so than Miller’s book on New York mammals published just a year earlier. Because of the scientific prose and content of his monograph on voles, Bailey further entrenched the new definition and concept of habitat within the emerging field of ecological science. The emergence of this new perspective on habitat was not limited solely to vertebrates; Hargitt (1901a, 1901b, 1901c) also separately distinguished habitat from type locality and geographic region in his three-part monograph on hydrozoans.

In 1907 Cora Daisy Reeves published a paper, “The breeding habits of the rainbow darter (Etheostoma caeruleum, Storer), a study in sexual selection ” As the title suggests, Reeves’ paper was primarily devoted to the reproductive behavior of darters. However, she also wrote about their habitat in detail. She described it as the rapids of swift-flowing streams and the pools in between rapids. She wrote about the darters being found among large stones and on a gravel sheet. Her description was also quantitative; she recorded that the water above the

Table 1.1 List of late-nineteenth-century naturalists who used the word “habitat” in a way now seen as archaic (to refer to a particular geographic region or locality) or not at all when writing accounts of particular species. List is selective and only includes authors that were actively writing at some time from 1850–1900. Naturalists are ordered chronologically by birth year.

NameBirth—deathSpecies groupRegion

John Edward Gray1800–1875Everything, corals to mammalsWorldwide

John Gould1804–1881BirdsUK, Australia, New Guinea, North, Central, and South America

Edward Blyth1810–1873Birds, mammalsIndia, Southeast Asia

Augustus Fowler1812—unknownBirdsPrimarily eastern North America

Gustav Hartlaub1814–1900BirdsEurope, Africa

John Henry Gurney, Sr.1819–1890BirdsEurope, Africa

Samuel Lockwood1819–1894Reptiles, fish, invertebratesNorth America

Henry Baker Tristram1822–1906Various groups but primarily birdsPacific islands and Middle East

Thomas Vernon Wollaston1822–1878Insects, primarily beetlesEurope

Spencer Fullerton Baird1823–1887Reptiles, birdsNorth America

Edgar Leopold Layard1824–1900BirdsSouth Africa, Pacific islands

John Lawrence LeConte1825–1883InsectsNorth America

Octavius Pickard-Cambridge1828–1917SpidersWorldwide

Philip Lutley Sclater1829–1913BirdsCentral and South America, Pacific islands

Albert Günther1830–1914ReptilesWorldwide

Daniel Giraud Elliot1835–1915Birds, mammalsNorth America

Edward Hargitt1835–1895WoodpeckersWorldwide

Tomasso Salvadori1835–1923BirdsItaly, India

Joel Asaph Allen1838–1921Birds, mammalsNorth and South America, Caribbean

Alpheus Spring Packard1839–1905InsectsNorth America

Edward Drinker Cope1840–1897Primarily reptilesWestern Hemisphere

Elliott Coues1842–1899Primarily birds, some mammalsNorth America

Charles Conrad Abbott1843–1919Fish, invertebrates, amphibiansPrimarily eastern North America

William Healey Dall1845–1927Primarily mollusksNorth America

Richard Bowdler Sharpe1847–1909BirdsGreat Britain, Africa, Asia

Robert Ridgway1850–1929BirdsNorth and South America

Hans von Berlepsch1850–1915BirdsNorth and South America

David Starr Jordan1851–1931Primarily fishNorth America

Clinton Hart Merriam1855–1942Mammals, birdsNorth America

Charles Barney Cory1857–1921BirdsNorth and South America, Caribbean

George Albert Boulenger1858–1937Reptiles, amphibians, fishWorldwide

Alfred Webster Anthony1865–1939Birds, mammalsWestern United States, particularly Pacific Coast

Harry Church Oberholser1870–1963BirdsPrimarily western United States, Mexico

Joseph Grinnell1 1877–1939Birds, mammalsPrimarily western North America

1 More so than the other naturalists, Grinnell eventually became thoroughly modern in his view of habitat.

Figure 1.3 Species description for the long-tailed vole (Microtus longicaudus) as presented by Vernon Bailey in Revision of American Voles of the Genus Microtus, North American Fauna Volume 17, 1900. This is the actual page from the monograph. Note that “type locality,” “geographic description,” and “habitat” are separate categories thereby indicating that Bailey explicitly recognized that habitat was more than just the geographic location where a species was found.

gravel sheet was 1.5–6 in. deep with a current velocity of 75 ft per min. The gravel pebbles averaged 0.5 in. in diameter. In addition to being one of the first quantitative descriptions of a species’ habitat, Reeves’ study also was one of the first to (1) recognize a distinction between the habitat of the species during the breeding and nonbreeding seasons, (2) provide an estimate of population density within the habitat, and (3) mention the presence of other similar species (fish) using the same habitat, namely creek chubs and stonerollers. To be thorough, the published paper also included an annotated photograph of the habitat. Reeves accomplished all this without habitat being the primary focus of her study. She presents very detailed information and interpretation of darter mating behavior—surely her study is also an early standard in the field of behavioral ecology. Although she never published a similar assessment of habitat (or reproductive behavior), Reeves went on to have a very interesting academic career nonetheless (Box 1.1).

In the early twentieth century, ecologists also began to use the term “habitat” in a theoretical context and not just as a category or label for the type of environment where a particular species lived. Leavitt (1907) reviewed the different theories regarding the necessity of geographic separation for the process of speciation. In so doing he recognized that the number of species of a given kind occurring within a region (he called it a “district”) might closely correspond to the number of different types of habitat in the region. He also stated that “difference of local habitat” could provide the isolation needed to preclude interbreeding of incipient species and he referred to the need for individuals to be adapted to their habitat. Although Leavitt did not discuss habitat as a necessary and broad concept within ecology and evolution, he did clearly use the term in a modern way and in the context of the contentious debate on whether natural selection or mutation was more important in producing new evolutionary forms.

Box 1.1 Cora Daisy Reeves

Cora Reeves (1873–1953) was born in Rockford, Illinois, United States but eventually found her way to the Pacific Coast where she enrolled at the California State Normal College in Los Angeles (later to become UCLA). She graduated in 1894 and later returned east to complete a PhD at the University of Michigan in 1917. Her dissertation research experimentally examined how fish perceive the wavelength of light. Soon after completing her dissertation, she was hired to the faculty at Ginling College in Nanking (Nanjing), China. The college had been founded only a few years previous by missionaries from the United States with the purpose of providing advanced education to Chinese women. Today, the college is part of Nanjing Normal University. Reeves remained at Ginling College until 1941 and upon her retirement she returned to the United States. Although Reeves’ academic career was primarily founded on teaching and administration, she routinely undertook collection of fish, reptile, and insect specimens as a graduate student in Michigan and then later as an academician in China. Some of her specimens still reside in the collections at the Museum of Zoology at the University of Michigan. She also wrote an 806-page “field guide,” Manual of the Vertebrate Animals of Northeastern and Central China, Exclusive of Birds, published in 1933. Reeves’ accomplishments are particularly

remarkable given the time period of her life and career. Reeves (1907) is not only one of the first scientific accounts of a species habitat, but it is likely also one of the first ecology journal papers written in IMRAD format, an approach to written communication of research that would become the standard in nearly all fields of science. In this regard, Reeves was also thoroughly modern—her name deserves to be better recognized among the early pioneers of natural history and ecology.

Robert Leavitt was actually best known as a botanist and author of several popular textbooks, not as an ecologist. However, he was a contemporary of plant ecologists such as Henry Cowles, Eugen Warming, Frederic Clements, Arthur Tansley, Henry Gleason, and Volney Spalding. The research and writings of these scientists greatly influenced the early development of ecology as a scientific discipline. They wrote about the process of succession, plant communities, and ecosystems, essentially demonstrating that ecology could be more than just the autecological study of the natural history of single species. These founders of modern ecology used the term “habitat” extensively in their writings, particularly Clements and Tansley. In his classic, Plant Succession, Clements (1916) used “habitat” hundreds of times, but in a way that we (students of modern-day ecology) use the word “environment.” Also, he never used “habitat” in reference to any particular plant or animal species. Plant ecologists of his day were primarily concerned with three main pursuits: figuring out ways of hierarchically grouping sets of co-occurring plant species, determining the abiotic and biotic factors affecting the distribution of plants, and studying natural temporal change in plant communities such as the process of succession. Their concept of habitat was compatible with each of these research arenas. To them, habitat was a physical place where all the environmental conditions were favorable for the development of certain plant communities or prohibitive in the development of other plant communities. Understandably, unlike animal ecologists they did not see the plant communities or vegetation as forming the habitat. Plant ecologists thought of habitat as a template of mostly abiotic physical factors upon which a plant community could develop and be maintained, and possibly transition to a different set of species through succession.

Clements’ ideas about succession and habitat were formed by his direct experience spending time in the natural landscapes of his native Nebraska. To him, habitat was more than just a particular place where certain plants grow.

Ecology concerns the relation of plants to their surroundings, both physical and biological. The habitat of a plant is an aggregate of influences or factors acting upon the plant and causing it to exhibit certain phenomena and structures more or less peculiar to the habitat and plant in question. Each habitat is dominated by one or more

controlling factors in the presence of which other factors are insignificant or ineffective. Taken as a whole, these factors constitute the physical environment of a plant, or its habitat. They are temperature, light, water-content, soil, atmosphere, precipitation, and physiography. (Paraphrased from Pound and Clements 1900, p.161)

[At the time, Roscoe Pound, only a few years older than Clements, was director of the state botanical survey in Nebraska, hence the order of authorship. Pound went on to have more of a career as a legal scholar than as an ecologist.]

Clements expressed a relatively modern concept of habitat and one that was a long way from the early Linnaean depiction of habitat as a specific geographic region or locality. Indeed, Tansley (1920) wrote about the impracticality of physically delimiting any single habitat and even suggested that reference to particular habitat types (especially as synonymous with plant formations or associations) was misguided. Beginning with Cowles and Warming, and continuing into modern times, plant ecologists have always used a very comprehensive and heuristic concept of habitat.

In the early twentieth century, there was a divide between plant ecologists and animal ecologists. Indeed, ecology was plant ecology or what was sometimes called phytogeography or botanical geography. Perhaps because of this divide, animal ecologists were a bit slower to develop a concept of habitat that was as theoretical and mechanistic in subscribing to habitat a central role in determining distribution and abundance of species. In essence, that was the key feature of “habitat” in plant ecology: habitat subsumes all the various environmental factors affecting the persistence of a species and communities. This mechanistic aspect of habitat was initially missing in how animal ecologists used the term “habitat.”

In the separate academic field of animal ecology, Joseph Grinnell is probably the person who deserves the most credit in bringing about a modern concept of habitat (Box 1.2). At first, Grinnell (1897) used the Linnaean definition in identifying the habitat of a new species of towhee as San Clemente Island off the coast of California; by the way, it is presently considered to be a subspecies Pipilo maculatus clementae. Interestingly, in this species account, Grinnell also identified a type locality with a little more geographic precision (Smuggler’s

Box 1.2 Joseph Grinnell

Joseph Grinnell (1877–1939) was born in the region that was known as “Indian Territory” at the time and which later became the state of Oklahoma. His father was a medical doctor assigned by the US federal government to serve groups of Native Americans at Fort Sill. When he was a child, his family moved to California where he would remain throughout his life. He received a PhD from Stanford University in 1913. Shortly prior to that, he became the first director of the newly created Museum of Vertebrate Zoology at the University of California, Berkeley, a position that he held for his entire career. Grinnell was a keen observer of vertebrate fauna in the field, writing extensively about how various species are adapted to the conditions of their habitats. He published 554 research papers, popular articles, and books between 1893 and his death in 1939 (Alagona 2012). He also was an early proponent of the need to preserve species and their natural habitats. This included, among many conservation accomplishments, a critical visionary role in establishing the University of California’s system of natural reserves dedicated to scientific research, education, and conservation (Alagona 2012). More so than any other person, Grinnell should be credited with bringing about our modern multi-faceted concept of wildlife

Cove) where a male and female had been collected just a few months prior. He did not otherwise describe the habitat. However, by 1904 he was transitioning. In a species account of the chestnutbacked chickadee (originally Parus rufescens but very recently Poecile rufescens), he describes the habitat as a long and narrow region along the Pacific Coast from southeastern Alaska to northern California, and he presents a map of this geographic range. But in the same paper, he also writes about its habitat as being dense, well-shaded, humid coniferous forest with substantial cloudiness and precipitation. Thus he was using “habitat” in both the old-fashioned sense of the word and its newly emerging usage as a descriptor for the vegetation and other environmental conditions where a species is found. Incidentally, he also suggested that the dorsal brown plumage coloration of the bird was an adaptation for the humid environment (though he does not give a mechanism). He further described geographic variation within the species, this included descriptions of several subspecies.

habitat. He recognized habitat as a general ecological concept as well as an extrinsic characteristic of a species. Further, his conservation advocacy also provided a physical reality to habitat. He saw that habitats were indeed places in nature that needed protection for their own sake as well as providing the places of residence for various wildlife species.

Lastly, Grinnell also suggested a very well thoughtout hypothesis on the origin of P. rufescens from another nearby species, P hudsonicus, which involved isolation due to habitat differences. In most respects, Grinnell (1904) was a very modern paper on the ecology and evolution of a species. By 1917 Grinnell was exclusively using “habitat” in its modern sense. In his study of the California thrasher (Toxostoma redivivum), Grinnell thoroughly described the chaparral habitat of the bird, including a detailed description of the breeding habitat and ways in which the foraging behavior of thrashers relates to the physical structure of the vegetation. More remarkably, Grinnell clearly recognized that a set of environmental factors (i.e., the habitat) was important in restricting the geographic distribution of the species. According to Grinnell (1917), “An explanation of this restricted distribution is probably to be found in the close adjustment of the bird in various physiological and psychological respects to a narrow range of environmental conditions. The nature of these critical conditions is to be

learned through an examination of the bird’s habitat” (p. 428). In recognizing habitat as a factor affecting the occurrence and spatial distribution of a species, it is easy to conceive that Grinnell may have read and been influenced by the studies of the plant ecologists that were emerging at the time. Grinnell (1917) is also the very first paper to use the term “niche” and present a description of a species’ niche; ironically although the word appears in the title of the paper, Grinnell only used it a few times at the very end of the paper. Nonetheless, the relevance here is that “habitat” and “niche” were used in the same paper and thus distinguished from one another. In the ecological literature, “niche” is not nearly as widely used as “habitat” (Fig. 1.1), but it is a very familiar term and concept to all ecologists. As a concept, niche is more complex, intangible, and theoretical than is habitat (Section 1.2).

The early divide between plant and animal ecologists was bridged somewhat by Victor Shelford (Box 1.3). There was a direct link: Shelford had been a student of Henry Cowles at the University of Chicago. As such, Shelford was influenced by Cowles’ pioneering study of plant succession in the Indiana Dunes, an extensive area of dune formation on the south shore of Lake Michigan. Perhaps due to a desire to carve out his own scientific career independent of Cowles, Shelford did not study plants. His organisms of choice were tiger beetles (family Cicindelidae). Shelford was one of the first ecologists to frequently discuss “habitat selection” and “habitat preference.” In his dissertation, Shelford (1907, 1908) described how female tiger beetles must find (i.e., select) the correct soil type and moisture conditions for egg-laying. This focus on studying the factors affecting habitat selection and preferences

Box 1.3 Victor

Ernest Shelford

Victor Shelford (1877–1968) was born in the small town of Chemung, New York. He received his PhD from the University of Chicago in 1907. He was then hired to the faculty at the University of Illinois in 1914 where he remained for his entire career. Shelford had an immense range of ecological research interests. He conducted field work and published research on mammals, birds, fishes, and insects in forests, grasslands, dune complexes, tundra, swamps, streams, rivers, and lakes. From 1914–1930 he spent his summers on the coast of the state of Washington studying various fish species as well as the pelagic and near-shore communities of marine invertebrates in Puget Sound (e.g., Shelford and Powers 1915; Shelford et al. 1935). He was also concerned with advancing the experimental study of animals in their natural habitats and laboratory settings. As such, he wrote papers on the proper methodology for and inferences from such studies (e.g., Shelford 1926, 1934, 1954; Shelford and Eddy 1929). Shelford even wrote textbooks on ecology. From our present-day perspective, his research contributions can be categorized within a wide range of subdisciplines: physiological ecology, community ecology, landscape ecology, population ecology, biogeography, and conservation biology. Shelford retained a lifelong interest in ecological succession, perhaps a holdover from his early days with Cowles. However, above all else, he was an experimentalist. He very much believed that an organism’s adaptation to its abiotic

environment affected its daily performance (survival and reproduction) as well as the habitats that it occupied and the geographic distribution of the species. He investigated his view of ecology and nature with carefully designed experiments that were thoroughly modern and scientific. Lastly, Shelford shared with Grinnell not only a birth year, but also a desire to protect native flora and fauna, which included advocating for the permanent protection of natural habitat (e.g., Shelford 1933, 1941).

would continue throughout his career, although he quickly moved on from insects to fishes and other vertebrates.

Considering that Shelford studied tiger beetles, it is easy to imagine how he began to think about animals actively selecting habitat. Tiger beetles are very fast runners, they fly well, and they have excellent vision. They are generally active for long periods of the day, moving about, always searching for something. Much of the time the searching is the hunting of prey; tiger beetles are aggressive predators, hence the name. Shelford observed this natural behavior of tiger beetles in the dune fields as well as the precise and deliberate egg-laying behavior of females—this involves careful construction of a burrow chamber, once the appropriate soil habitat is found (Shelford 1908). He must have been impressed by the seemingly deliberate and careful behavior of the beetles.

In 1911 and 1912, Shelford published a five-part series of papers in the Biological Bulletin. This was likely the first attempt to apply the process of succession to animal communities, both aquatic and terrestrial. In part I, Shelford discussed how a stream might have different sets of fish species at different locations as the stream aged becoming deeper and wider through erosion and incision; that is, successional change in a stream. He also presented data on the collecting localities of numerous fish species in several creeks that drained into Lake Michigan near Chicago. He clearly saw habitat preferences and the implied capacity for fish to select habitat as being important to their distribution, writing “Fishes have definite habitat preferences which cause them to be definitely arranged in streams which have a graded series of conditions from mouth to source” (Shelford 1911, p. 33). Further, in this paper and others, he stressed that animals must be physiologically and structurally adapted to the environmental conditions of their specific habitat. This led him to measure particular environmental factors in different habitats, such as the penetration of light through the canopies of forests at different successional stages (Shelford 1912a).

The rate of evaporation—early on in his scientific career Shelford identified this as a crucially important factor in all habitats, and he measured, studied, and wrote about it his entire life. He was the first animal ecologist to identify a particular abiotic

(edaphic) habitat factor and attribute importance to it from both a theoretical standpoint and with regard to empirical observation (Shelford 1911, 1912a). Again, he was influenced by plant ecologists. According to Shelford (1912a), over decades of study, plant ecologists had come to realize that rate of evaporation was the best descriptor of plant environments. In the same paper, he also noted that spiders and insects captured on the prairies will quickly die when placed in screened cages in the laboratory but will survive if kept in glass-enclosed containers. He attributed the mortality to evaporation of water from the organisms’ bodies, that is, desiccation. To Shelford, rate of evaporation was a common measuring stick to compare among different habitat types. He regarded the “evaporating power of the air” as the most inclusive and best index of the environmental conditions that an animal was exposed to (Shelford 1912a). Perhaps because he was able to a priori identify factors presumed to be important in habitat selection, Shelford went so far as to perform experiments on how animals select habitat (Shelford 1915). Some of these experiments even involved captive organisms. Due to his research on organism–environment interaction, Victor Shelford is also considered a founder of physiological ecology.

He can also be considered a founder of community ecology. In the 1912 series of papers, he thoroughly establishes the idea that different animal species at a given location constitute a community just as much as do the plant species. Shelford also set the stage for thinking about vegetation (i.e., plant communities) as habitat for animal communities, an implicit notion of habitat that still persists today. Much of Shelford (1912b) is devoted to an attempt to find ways of classifying habitats and putting “habitat” as a real unit of nature into the hierarchy of biological organization. Plant ecologists had been up to this task for several decades and they were following the lead of Linnaean taxonomists to essentially classify nature. Of importance, Shelford (1912b) was also attempting to define the emerging academic field of ecology and set it apart from natural history. As an example, he wrote “The work of naturalists is important though it is defective mainly in that one often has difficulty in determining what habitat is meant” (p. 336).

Victor Shelford was extremely productive. In 1913, he published Animal Communities in Temperate

America, a 362-page book that would go on to influence the intellectual development of ecology for decades. The book further developed all of Shelford’s ideas on the importance of habitat, among other things. In these past six paragraphs on Victor Shelford, I have unintentionally short-changed him a bit. He contributed enormously to the growth of ecology as an academic and research discipline; and Shelford helped advance many of its different subdisciplines—this cannot be overstated. He even saw this as a duty and often referred to the need to “make progress” in ecology. Most of his papers and books still have great relevance today. For the particular purpose of this book, his greatest contribution was in bringing about a very multi-faceted concept of habitat that is integral to the many ecological processes and patterns that we still study today.

Lee Raymond Dice was another important ecologist who contributed to the development of our modern concept of habitat (Box 1.4). For his disser-

Box 1.4 Lee Raymond Dice

Lee Dice (1887–1977) was born in Savannah, Georgia, but moved with his family to Washington State at an early age. As an undergraduate student, he briefly attended Washington State Agricultural College (now Washington State University), the University of Chicago, and then Stanford University. While at the University of Chicago, he enrolled in Victor Shelford’s course in animal ecology. He was immediately hooked on the subject matter; the course was an early and profound influence in his career development (Evans 1978). Dice obtained his PhD in 1915 from the University of California, Berkeley partially under the direction of Joseph Grinnell. Upon completing his doctoral degree, Dice was employed at various universities and government agencies until 1919 when he accepted a permanent position in the Department of Zoology at the University of Michigan where he remained employed until retiring in 1957. Although Dice started his career as a mammologist and field ecologist, his career eventually came to include an eclectic mix of research topics. He conducted research on the genetics of deer mice (Permoyscus) and this eventually led to an interest in the genetics of human epilepsy (Evans 1978). He had early and lifelong interests in paleontology and biogeography (Evans 1978). He even developed a statistical index to measure the amount of “ecological association” between species (Dice 1945). Despite seeming to have many admin-

tation at the University of California, Berkeley, Dice studied the vertebrate communities in his home state of Washington, particularly the southeastern corner. He spent much time in the field, observing birds during the day and trapping mammals by night—in a way reminiscent of the early naturalists. However, his intent was very ecological and modern. He wanted to understand the extent to which habitat determined the spatial and geographic distribution of species, a pursuit that ecologists still work on today. Dice (1916) described the “ecological method” as a way of describing “animal distributions” based on studying the adaptive relationships of organisms with their environment. Dice provided lists of various mammal, bird, reptile, and amphibian species found in different major habitat types (vegetation associations). In addition to thoroughly describing the vegetation in each habitat type, he presented detailed climatological information for the habitats. In so doing, Dice (1916)

istrative duties at the University of Michigan, Dice managed to remain engaged in field research, often in relatively far-off places such as Arizona and New Mexico (Evans 1978). From the very beginning of his career, Dice recognized and used the modern concept of habitat. His contributions to the historical development of ecology and wildlife ecology are not as well-known as those of Grinnell and Shelford, but they should be.

furthered the idea of vegetation as habitat for animals and recognized a very comprehensive concept of habitat that took into account abiotic and biotic conditions. Several years later, he conducted a similar study in Montana (Dice 1923). He was very interested in the extent to which structurally- and climatologically similar habitats in different regions might harbor similar animal species. He considered the ecological method of studying species–habitat relationships as transcendent among habitats and regions, applicable to any place on the planet.

In a synthesis paper, Dice (1922) more closely linked animal communities to the habitat concept and he described the need for a new system of ecological classification based on habitats and ecological communities. He appealed to field biologists (museum collectors) to record detailed information on the habitats where their specimens were collected. Dice saw such information as being extremely valuable to ecologists in learning more about the multiple factors that affect (restrict) the distribution of species in nature. He also emphatically commented on the urgency of this task. Even way back in 1922, he recognized that natural habitats were disappearing fast due to humankind’s activities and a rapidly modernizing world:

There is pressing need that the work of describing the biotic areas and habitats of the world should be speedily done . . . in our more settled districts it is now difficult or impossible to find even small areas of the original habitats. It is important to determine quickly the habitat preferences of the native plants and animals. It behooves us to record all we can of natural habitats and habitat preferences before it is too late. (p. 338)

This was prescient writing by Dice and crystal-clear recognition of a concern that still exists today. Meanwhile, the occupational divide between plant and animal ecologists continued into the 1920s. Yapp (1922) discussed different definitions or concepts of habitat but did not cite any of the papers of the animal ecologists and he even claimed that animal ecology was lagging behind plant ecology. He presented a concept of habitat that was spatially abstract and multi-level. Yapp saw a difference between the habitat of an individual plant, a community of plants, and even groups of related plant communities (as in succession). He also said that it was

impossible to physically delimit the outer spatial boundaries of any habitat. To Yapp, habitat consisted of the factors or conditions of the environment that the physiology of an individual plant (and by extension plant communities) must be adapted to, or else the plant would not exist where it does. According to Yapp, “Apart from the factors, the habitat, from the point of view of ecology, is little more than an abstraction” (p. 11)—this was a concept that did not catch on entirely. Nonetheless, Yapp advanced our modern concept of habitat by suggesting that habitat could be viewed and studied in the abstract without reference to a spatial location or the physical structure of vegetation or anything else. Although Yapp separated the concept of a plant association from habitat as a concept, he did acknowledge that animal species might be associated with certain plant communities and such associations were worthy of further study. Eventually, the gap between plant and animal ecologists was closed somewhat with the joint authorship of a book by Clements and Shelford in 1939. To some extent, the early notions of habitat as held by animal ecologists were too much tied to the process of succession. That is, animal ecologists were interested in discovering the animal equivalent to plant succession. Of course, the succession of animal communities is a real process in nature. But the habitat relationships of animal species can certainly be studied without reference to succession.

As early as 1905, Clements had called for a quantitative analysis of habitats, but what he really meant by habitats was plant formations or associations (see also Clements 1913). He desired statistical methods for elaborating the process of succession, regardless of learning more about vegetation as habitat for animals. Further, Shelford and other animal ecologists had introduced an experimental and quantitative approach to the study of habitat selection, although it was very rudimentary by today’s standards. Through the 1920s, the modern concept of habitat was becoming better established even though a quantitatively rigorous assessment of a species–habitat relationship had yet to appear.

Perhaps the first quantitative and statistical analysis of the habitat associations of species was Georgy Gause’s study of grasshoppers near the city of Sochi in the USSR. Of course, Gause is otherwise well-known to ecologists for his experimental

research and writing on the Principle of Competitive Exclusion. Prior to becoming a population biologist and antibiotics researcher, Gause was studying the habitat associations of grasshoppers (Box 1.5). He was only 19 years of age when he wrote “Studies on the Ecology of the Orthoptera” and managed to get it published in Ecology, one of the very first ecological journals. The year was 1930 and this was one of Gause’s first scientific papers and the first written in English. Although Gause does not mention any practical motivation for studying grasshoppers, we can assume there was one. Grasshoppers were major pests of the vast grain crops under cultivation in the burgeoning USSR, so Gause or his superiors were probably tasked with learning more about the ecology of these organisms. Gause’s analysis of the habitat associations of 15 grasshopper species was remarkably sophisticated for the day. Even by today’s standards, his analysis is thorough and appropriate; it would be publishable in any number of ecological or entomological journals.

Gause recorded the abundances of the grasshopper species in 400 m2 plots in each of 21 sampling localities (or “habitats”). Based on previous studies of other scientists, Gause knew that the different grasshopper species differed in the level of humid-

Box 1.5 Georgy Gause

Georgy Gause (1910–1986) was born in Moscow, Russia. He was admitted to Moscow State University where he received his undergraduate degree in 1931 and PhD in 1940. Prior to achieving his doctoral degree, Gause was already conducting research and writing about the mathematical underpinnings of population biology. For example, he published his ecological classic, TheStruggleforExistence, in 1934 (and in English!). This book and similar research papers in the 1930s helped lay the early foundation for population ecology and indeed fostered the introduction of mathematics into the historical development of ecology. In ecology, Gause’s contributions are equally acknowledged along with those of other early ecologists who studied population dynamics; for example, Vito Volterra, Alfred Lotka, and Raymond Pearl. However, most ecologists are not aware that Gause eventually went on to conduct very important research on antibiotics (Kodash and Fischer 2018) and somewhat left ecology behind. Nonetheless, his simple yet elegant experiments on the coexistence (or lack thereof) of Paramecium remain as the classic empirical demonstration of competitive

ity that they required or tolerated. Further, he reasoned that the vegetation in each plot produced a certain microclimate (and yes he used that term) with a particular level of humidity. Therefore for each of the habitats he measured plant biomass and height in 1 m2 plots. Then he placed each habitat into one of six categories that represented a progression from xerophytic conditions with little vegetative cover to mesophytic conditions with dense cover to a hydrophilic condition represented by a damp meadow. The latter habitat category had on average about 20 times the vegetative biomass of the most xerophytic category.

Gause described his grasshopper habitat analysis as “a study of the distribution of organisms in relation to the factors of the environment” (p. 307), which he regarded as a fundamental pursuit in the still relatively new science of ecology. In addition to ecological interests, Gause evidently had excellent training in math and statistics. In general terms he described a plot of data in which an environmental factor was on the x-axis and species abundance on the y-axis. He then stated that from the plot, “we will obtain a curve representing the relation which exists between abundance and the given factor” (p. 307). Gause wanted to find the mathematical

exclusion. Gause was a gifted ecologist and mathematician. If his research interests had remained within ecology, no doubt he would have continued to make meaningful contributions.

expression for the connection between the two variables, the environmental factor and species abundance. He suggested that the abundance data for a given species spread over the habitat categories could be described as a binomial curve (Fig. 1.4). He further stated that so-called ecological curves follow the Law of Gauss (a reference to Carl Friedrich

Gauss, the great nineteenth-century mathematician). Gause was likely referring to the fact that binomial distributions can sometimes be approximated by normal (i.e., Gaussian) distributions, even though the former are discrete and the latter are continuous. Binomial distributions derive from binomial processes wherein there are only two possible outcomes (e.g., yes/no, pass/fail, present/ absent). Modeling the species–environment relationship as the result of a binomial process is very reasonable in that an individual of the species either is present in or absent from a sampling plot that has a given value(s) of the environmental factor(s)— and presumably presence/absence might be due to one or more of the environmental factors, although Gause did not explain it like this. By extension, the proportion of individuals of the given species in each habitat would follow a binomial distribution (Fig. 1.4). Thus, Gause was envisioning the six habitat categories arranged along the x-axis (as a single comprehensive environmental variable) and observed proportional abundance of each species plotted on the y-axis. In this way, an abundance curve for each species could be derived and analyzed as well as species compared with one another (Fig. 1.5). Of note, Harris et al. (1929) had also suggested a similar statistical comparative approach but without applying it to a particular species.

Figure 1.4 Binomial distributions derive from a binomial function that gives the probability of x “successes” for a given number of “trials” and a given probability of success during each trial, P(x) = (n x )px (1 − p) n − x, where n = number of trials and p = probability of success. The establishment and existence of an individual of a given species in a sampling plot of a given habitat category can be conceived as a binomial process. In that scenario, a “trial” is a given level of an environmental factor and a “success” is the individual being able to exist in a plot given that level of the environmental factor. In (a) there are six habitat categories (or levels) and p = 0.5. Category 1 is a default category and represents zero successes out of six trials. Category 2 includes individuals that had one success. Category 3 represents individuals that had two successes, and so on. In this example, the proportional abundance of the species is identical to P(x = X) for each X = 0 to 5, representing the six habitat categories. Any number of habitat categories or levels of an environmental factor could be described by a binomial distribution and p could be a value other than 0.5. In (b) there are 10 levels and p = 0.7, in (c) there are 10 levels and p = 0.3.

Somewhat ironically, despite the elegant statistical framework, Gause did not actually make much use of the curves. In principle, he could have tested to see if each curve departed from a random distribution (which would be manifested as a symmetrical hump-shaped curve) or perfectly even distribution (which would be represented as a horizontal line) (Fig. 1.5). A relatively simple goodnessof-fit test (e.g., chi-square test) would have sufficed for this task. To his credit, Gause may have recognized the limits to his data—he had only six habitat categories and hence his environmental variable was very discrete (not continuous) and thus perhaps not very suitable to discriminating a normal distribution. Gause actually alluded to this issue briefly in stating that “the approach to the binomial curve of distribution depends on the number of variants” (or habitat categories) (p. 317).

Nonetheless, Gause made good use of his data. For each species, he calculated the weighted mean

lilifolia

Chorthippus albomarginatus

italicus

Acrydium bipunctatum

Figure 1.5 Proportional abundances of Gause’s grasshopper species distributed among the six habitat categories ranging from xeric (1) to mesic (6) conditions. Gause (1930) did not present the data in this way although he describes “abundance curves.” Some of the species have an approximately normal distribution (e.g., Stauroderus buguttulus, Chorthippus albomarginatus), being found throughout most of the moisture gradient with a peak in abundance in habitat category 3 or 4. Other species clearly seem to associate with either xeric (e.g., Aiolopus thalassinus) or mesic (e.g., Conocephalus fuscus) conditions. No species has a uniform distribution that would be evident as the same proportional abundance (1/6 = 0.167) in each habitat category.

of its abundance among the six habitat categories ordered from dry to wet, M = Σ(J × wj) for J = 1 to 6 and wj = the proportional abundance of the species in habitat category J. Thus, species with low M values were taken to be xerophytic and those with high values were considered mesophytic. Gause also calculated the standard deviations of the M values, in the typical way for a weighted mean, sd = Σ(mj M)2 with mj = J × wj. This allowed him to compare species and discover that most species were different from one another in where they fell along the continuum of dry to wet environmental conditions (Fig. 1.5). Further he considered the standard deviation to also be a measure of the ecological plasticity of each species or the extent to which the species is found in multiple habitat types and can survive in a wide range of environmental conditions. To compare the ecological plasticity of each species, Gause determined the standard error (i.e., the standard deviation of the |mj M|values) of each species plasticity value. Again he found the species were

Box 1.6 David Lambert Lack

David Lack (1910–1973) was born in London, England. From an early age, he had an interest in birds and even published studies of bird behavior while an undergraduate student at Cambridge University. As a young man, Lack actually crossed paths with Joseph Grinnell, meeting him in August 1935 when Lack visited the Museum of Vertebrate Zoology at the University of California, Berkeley after a cross-country road trip (Anderson 2013). Lack received his ScD (PhD) from Cambridge University in 1948. His entire career was spent as director of the Edward Grey Institute of Field Ornithology at Oxford University. Lack’s main interest in habitat was concerned with the role that habitat differences played in the speciation process as well as permitting coexistence of similar and potentially competing species in the same general region. By the 1940s he was clearly influenced by Gause and the Principle of Competitive Exclusion (Anderson 2013). Lack also studied the life histories of various bird species and the ways in which density-dependent processes regulated population size. He often saw natural selection at work in molding the behavior and traits of birds. He is probably best known for the idea that clutch size is a species-specific trait that maximizes the parent birds’ fitness when the number of eggs laid corresponds to

different in their plasticity values or tolerances. Thus, his statistical analysis of the data enabled him to conclude that “the mean value, which characterizes the average conditions, and the dispersion, which is the indicator of ecological plasticity, are on the whole very characteristic for each species” (p. 320). By taking an analytical approach, Gause discovered distinct habitat associations of the grasshopper species that might not have been as evident by merely observing the species in the field and writing a narrative description in the manner of the old-time naturalists. Again, Gause accomplished this in 1930, many years prior to the advent of the advanced statistical procedures that we have today. Through the 1930s, our modern concept of habitat became more comprehensive and its central role in understanding many ecological processes became more widely recognized. As an example, the wellknown ornithologist and evolutionary ecologist David Lack conducted pioneering studies of habitat selection in birds (Lack 1933, 1934) (Box 1.6). He

the number of nestlings that the parents will have the greatest success in fledging. This hypothesis is now widely known in behavioral ecology and ornithology as Lack’s Principle. It is difficult to overestimate David Lack’s contributions to ecology, ornithology, and behavioral ecology, particularly with regard to the evolutionary context he imbued in each of these disciplines.

sought evolutionarily based explanations for how and why certain species preferred specific habitats and in particular he attributed much of the selection process to innate behavior or what he often called the “psychological factor” (Lack 1933, 1937). Ultimately, Lack was interested in the factors that limited bird distribution and abundance, a pursuit of ecological understanding that he shared with many other fellow animal ecologists. However, to Lack, the limiting factor could be something as complex as a direct behavioral response to the physical structure of the habitat rather than an automatic physiological response of the animal to a physico-chemical factor in the environment. The latter had been the focus of many previous animal ecologists, particularly those studying invertebrates and fishes. Thus, Lack pushed forward the need to understand and thoroughly characterize the habitat of a species—it was a necessary step toward investigating ecological and behavioral processes. In short, during the 1930s, ecologists began to recognize the benefits of studying the relationship of the organism (species) itself to its habitat in addition to merely identifying and describing its habitat (Klauber 1931; Pearson 1933; Boycott 1934; Edge 1935; Mosauer 1935).

The 1930s also saw the birth and development of a new academic discipline, wildlife ecology. Initially this discipline was better known as wildlife management. Aldo Leopold is widely acknowledged as its founder, with wildlife management becoming recognized as an academic discipline when Leopold published Game Management in 1933 and acquired a professorship of game management at the University of Wisconsin in the same year. The title aptly described the book—it was about managing game species (notably upland bird species and deer) for the purpose of maintaining populations that could be harvested or hunted. Somewhat ironically, the book did not have any discussion of habitat (Leopold used the word “habitat” only six times in the entire book) although habitat management has become a huge part of wildlife ecology and conservation in the past five decades or so (see Chapter 2). Leopold’s main goal was to discuss how the productivity (i.e., population growth rate) of a game species could be increased by identifying and then manipulating the factors that were restricting the population. These factors included food supply,

water, nesting sites (for birds), predators, disease, and vegetative cover to hide from predators and to shelter from weather. Leopold referred to “coverts” as patches of vegetative cover and discussed how these could be created or modified—essentially he was advocating for habitat management. Leopold certainly recognized the broader ecological concept of habitat; he simply did not use the word much.

Herbert Stoddard’s Bobwhite Quail: Its Habits, Preservation, and Increase, published in 1931, was perhaps the first discussion of habitat in the context of conservation and management of a harvested species. Stoddard’s book is remarkable for its thoroughness in covering all aspects of bobwhite biology and ecology, including the species economic and cultural importance as a game species that had been hunted in America since European settlement. In Game Management, Leopold discussed Stoddard’s research on bobwhite quail at length, and clearly admired the holistic and comprehensive approach of Stoddard. In addition to bobwhite quail, wildlife ecologists conducted habitat studies and implemented management for other wildlife species during this time period, such as muskrat (Errington 1937, 1940; Hamerstrom and Blake 1939; Bellrose and Brown 1941; Lay and O’Neil 1942), gray and fox squirrels (Baumgartner 1939; Goodrum 1940; Baker 1944; Brown and Yeager 1945), white-tailed deer (Hosley and Ziebarth 1935; Morton and Sedam 1938; Buechner 1944; Cook 1945; Allen 1948), and various waterfowl species (Girard 1941; Low 1941; Lynch 1941; Wiebe 1946; Mendall 1949). Although these and other wildlife studies rarely included an analysis of habitat that was as quantitative as Gause’s (1930) study of grasshoppers, they did accomplish one crucial step forward. By focusing on the management of habitat as a way to maintain and increase populations, these studies attempted to discover the habitat requirements of species. Therefore in a sometimes subtle way, the early wildlife ecologists implicitly reinforced the idea that suitable habitat is required for a population’s persistence and species’ existence—even today this remains a main reason for conducting an analysis of habitat.

In general, by the 1940s, the modern perspective on habitat was firmly established in ecology and becoming more important in wildlife ecology. Several comprehensive ecological textbooks had appeared

in the previous decades. Textbooks often have a subtle but widespread effect on the development and growth of a concept within an academic field. When something makes its way into a textbook then it is definitely knowledge that the elders want to pass on to the students of the discipline. As examples, we have Adams (1913) Guide to the Study of Animal Ecology, Pearse (1926) Animal Ecology, Elton (1927) Animal Ecology, Clements and Shelford (1939) Bio-ecology, and Allee et al. (1949) Principles of Animal Ecology. These books are still relevant today and worth browsing through—you will be surprised at how long we’ve been aware of some ecological concepts and processes that we still study nearly a century later.

1.2 Definitions and terminology

In any field of study or academic topic, precise terminology is important. Up to now, I have intentionally avoided giving a verbatim definition of “habitat.” Rather, by describing the habitat concept and putting usage of the term “habitat” in a historical context, my hope was that a definition of habitat would implicitly emerge in the reader’s mind (granted, most readers come to this book with some notion of habitat anyway). Nonetheless, I will now be more precise. However, I first comment on some definitions by other authors. Hall et al. (1997) defined “habitat” (paraphrasing) as “the resources and conditions in an area that lead to survival and reproduction, relating the presence of a species, population, or individual to an area’s physical and biological characteristics, implying more than vegetation and vegetation structure, the sum of the specific resources that are needed by organisms” (p. 175). Morrison et al. (2006) then refined this definition and made it more detailed with regard to identifying the resources and conditions. They stated “Habitat is an area with a combination of resources (like food, cover, water) and environmental conditions (temperature, precipitation, presence or absence of predators and competitors) that promotes occupancy by individuals of a given species (or population) and allows those individuals to survive and reproduce” (p. 10); this definition was also advocated more recently by Mathewson and Morrison (2015) and Krausman and Morrison

(2016). It is a thorough and comprehensive definition but it has some fairly subtle implications that could limit its usefulness.

A careful reading of the above definitions implies that once a habitat loses a particular required resource (e.g., food) or gains a negative influence (e.g., a predator species) and thus conditions do not lead to survival and reproduction, then the area ceases to be habitat. These definitions do not allow (explicitly) for habitat to be unoccupied and by extension they do not recognize that species often do not saturate their habitat in a given region. A habitat that has a diminished food supply, excessive predator density, or that is difficult to reach or colonize is still habitat for a prey species, it simply is not occupied for obvious reasons. The definition provided by Morrison et al. (2006) fits very well with what we might call realized habitat, or the area where the species is actually found due to the area’s combination of resources and conditions allowing survival and reproduction (i.e., occupancy).

Block and Brennan (1993) provided a very succinct definition of habitat as “the subset of physical environmental factors that a species requires for its survival and reproduction” (p. 36). Note that their definition implies that the habitat contains the resources for survival and reproduction without stating whether the species actually does survive and reproduce or even occupy the habitat—this is an improvement on the Hall et al. (1997) and Morrison et al. (2006) definitions in that it does not require occupancy. In most modern definitions of habitat, it is implied that the conditions and factors of a species’ habitat typically facilitate and perhaps are required for survival and reproduction of individuals. Hence, the phrase “survival and reproduction” need not be a formal part of the definition of habitat. Indeed, intentionally omitting the phrase then is a way around the paradox identified by Van Horne (1983)—that is, the density of a species in a particular area may not necessarily indicate that the area consists of habitat that allows for survival and reproduction. Further, Mitchell (2005) criticized abundance-based definitions of habitat in that (according to him) they are only valid when abundance of the species is maximized; that is, the habitat is saturated. Otherwise, it is impossible to know whether a given area truly is habitat in the sense of