Acknowledgments

Any piece of writing is necessarily the product of many minds. Every book is made from an assemblage of voices, of hints and gentle nudges, pieces of advice and long-held concerns, heads both shaken and nodded. Of this vast assemblage, I am most grateful for the nods and shakes of two people in particular: Jack Hawley and Rachel McDermott. Individually and collectively, they exhibit an enviable balance of brilliance and compassion. Not only has their work provided a model for academic excellence, but their capacity for warmth and support has been an enduring source of inspiration for living life—both inside and outside of the academy. It is hard to put into words what I owe them.

This project began as a series of conversations with friends and mentors at Columbia University. For those conversations and more, I want to thank Joel Bordeaux, Patton Burchett, Allison Busch, Divya Cherian, Elizabeth Castelli, Dan del Nido, Ryan Hagen, Udi Halperin, James Hare, Jon Keune, Abby Kluchin, Joel Lee, Ben Fong, Dalpat Rajpurohit, Jay Ramesh, Rakesh Ranjan, Simran Jeet Singh, Hamsa Stainton, Michael Taussig, Somadeva Vasudeva, Anand Venkatkrishnan, and Tyler Williams. Todd Berzon and Sajida Jalalzai read chapters at an early juncture in the writing, and helped me to clarify and contextualize many of the ideas that form the basis of this book. I am particularly indebted to Liane Carlson, who read a number of my chapters at a very shabby stage and who allowed me to ramble about my work over probably too many Happy Hours. Thanks also to my dissertation committee—Courtney Bender, Katherine Ewing, and Ann Gold—for helping me to translate those more difficult ideas locked in my mind into compelling words on a page.

I have presented parts of this book, in various stages and instantiations, at a number of venues: the American Academy of Religion, the American Anthropological Association, Columbia University, the International Conference on the Forum of Contemporary Theory (in Mysore), Syracuse University, and the University of Wisconsin-Madison. In those locales, I was fortunate to speak in front of audiences that were both receptive and generous; in particular, I appreciate the critiques, encouragements, and well-wishes of Carla Bellamy, Koya Edoho-Eket, Afsar Mohammad, Pritika Nehra, Corrie

Norman, Christian Novetzke, Andrea Pinkney, Sheipra Rajanikanth, and Sue Wadley. This book would not have been possible without the institutional and financial support of the American Institute of Indian Studies (AIIS), the Jacob K. Javits Fellowship, the Fulbright IIE, the Charlotte W. Newcombe Doctoral Dissertation Fellowship, and Columbia University’s Institute for Religion, Culture, and Public Life. The AIIS program in Jaipur was so important to me—a year in which I solidified my grasp of Hindi, found a fieldsite in Pushkar and, most importantly, met my wife. For their support throughout that year, I want to offer special thanks to Vidhu Chaturvedi, Neelam Bohra Singh, and Anita Tripathi.

In Pushkar, there are so many people to thank. First, I extend my gratitude to all the fine folks by Brahm Ghat, who welcomed me and my prying eyes. I want to thank the Pandey family, and Hemant Pandey in particular, for making me feel as if their home was mine, too. Dharma and Ravi Parashar were especially supportive, providing love and laughs and chai on a daily basis. As a research assistant, Ravi helped me access ideas and people who would have otherwise remained inaccessible. I am also deeply grateful to Ashok and Madhu Parashar—and their sons Kuldeep and Pradeep—my family in India. Their support I will never be able to pay back.

There are several friends and colleagues who have read chapters, offered insight, or shared their thoughts on some facet of my work. I am grateful to Carol Babiracki, Adam Becker, Sravani Biswas, Arun Brahmbhatt, Stephen Christopher, Greg Clines, Ruthie Dibble, Elaine Fisher, Anya Foxen, Dan Heifetz, Carter Higgins, Amy Hirschtick, Yoshina Hurgobin, Borayin Larios, Andrew Nicholson, Elayne Oliphant, Jenn Ortegren, Jef Pierce, Geoff Pollick, James Reich, Nidhi Vij, Emera Bridger Wilson, Ian Wilson, and Angela Zito. I have to single out Kali Handelman, my dear friend and editor, who read the manuscript multiple times and who was able to airlift me out of the forest of this book when my nose was rubbing against the bark of a tree. Kali’s patience and incisiveness made this book many times better than it would have been. Thank you, Kali.

San Diego State University has been my institutional home since 2016, and there I have found friends and colleagues who—whether through books, lunches, or soccer—have made my life richer. I thank Rebecca Bartel, Raechel Dumas, Stephen Goggin, Risa Levitt Kohn, John McDonald, Khaleel Mohammed, Javier Núñez, Casey Roulette, Kate Rubin, Sthaneshwar Timalsina, Kim Twist, Isaac Ullah, and Roy Whitaker. At Oxford University Press, Cynthia Read and Drew Anderla have been encouraging from the

start. My thanks to them for their guidance and positivity, and for doing all of the nitty-gritty stuff that went into making this book. The reviewers for the book were also extremely helpful. The feedback of Jim Lochtefeld, in particular, was thorough yet sympathetic, pushing me to make substantive changes while still keeping faith in the overall project.

Parts of this book have been published elsewhere. An earlier version of chapter 1 was published as “In Defense of Brothering: the ‘Eternal Religion’ and Tourism in North India,” in the Journal of the American Academy of Religion 84.4 (2016): 973–1005. An earlier version of chapter 2 was published as “Making Pushkar Paradise: Hindu Ritualization and the Environment,” in the International Journal of Hindu Studies 21.2 (2017): 187–210. And small sections of chapter 5 were initially part of “Spreading Peace in Pushkar: Shanti, Tourism, and Hindu Hybridity,” in the Journal of Contemporary Thought 38 (2013): 65–71. I am grateful to Oxford University Press, Springer Nature, and the Forum on Contemporary Theory for permission to reprint materials from these articles.

I thank my father and mother, Mark and Doreen Thomases, for not being too horrified when I decided to study religion and for encouraging me— despite their worries—to live far away, in India. My daughter Zinnia was born when I was in the middle of writing this book. Her spontaneity and charm have been such striking reminders of what matters in life. She has helped me so much, all the while not knowing or caring for a single second about this book. Finally, to Jocelyn Killmer I owe too much. She has read nearly every page that I have written over the past many years, and it is only because of her love that I have managed to keep writing. This book, and everything else, is dedicated to her.

Introduction

Mapping Out Paradise

October 2

I descended the broad marble stairs (ghats) toward the lake. It was a bright and cool morning, the sky an unbroken blue. A teenager named Vishnu sat on a huge metal trunk selling birdseed by the bowlful.1 Close to the water’s edge, a few pilgrims removed their sandals and tossed seed to a flock of pigeons. There were nearly a hundred of the birds, all flapping and strutting around the morning’s meal. Trying to strike up a conversation, I told Vishnu that where I was from, in the United States, pigeons are usually considered a nuisance. He countered, saying, “Well, in a future life, I would like to be a pigeon in Pushkar.” “But why?” His answer: “Because Pushkar is heaven” (pushkar svarg to hai).

November 16

Sitting on my favorite stone bench, I looked out over the water. Faraway loudspeakers crackled and hummed as they discharged distorted sounds of a Hindu recitation on the other side of the lake, utterances I’d been told transmit positive vibrations out into the ether. I scribbled some thoughts in my notebook, its pages stained with chai and oil, turmeric and spaghetti sauce. A brahman priest by the name of Mukesh came to look over my shoulder and see what I was writing. He feigned interest for a minute, and then asked for the notebook and my pen. He wanted to share with me a Hindi couplet he had thought up years before, something that brought a wide smile to his dimpled cheeks:

nim ka per chandan se kam nahin pushkar shahar london se kam nahin.

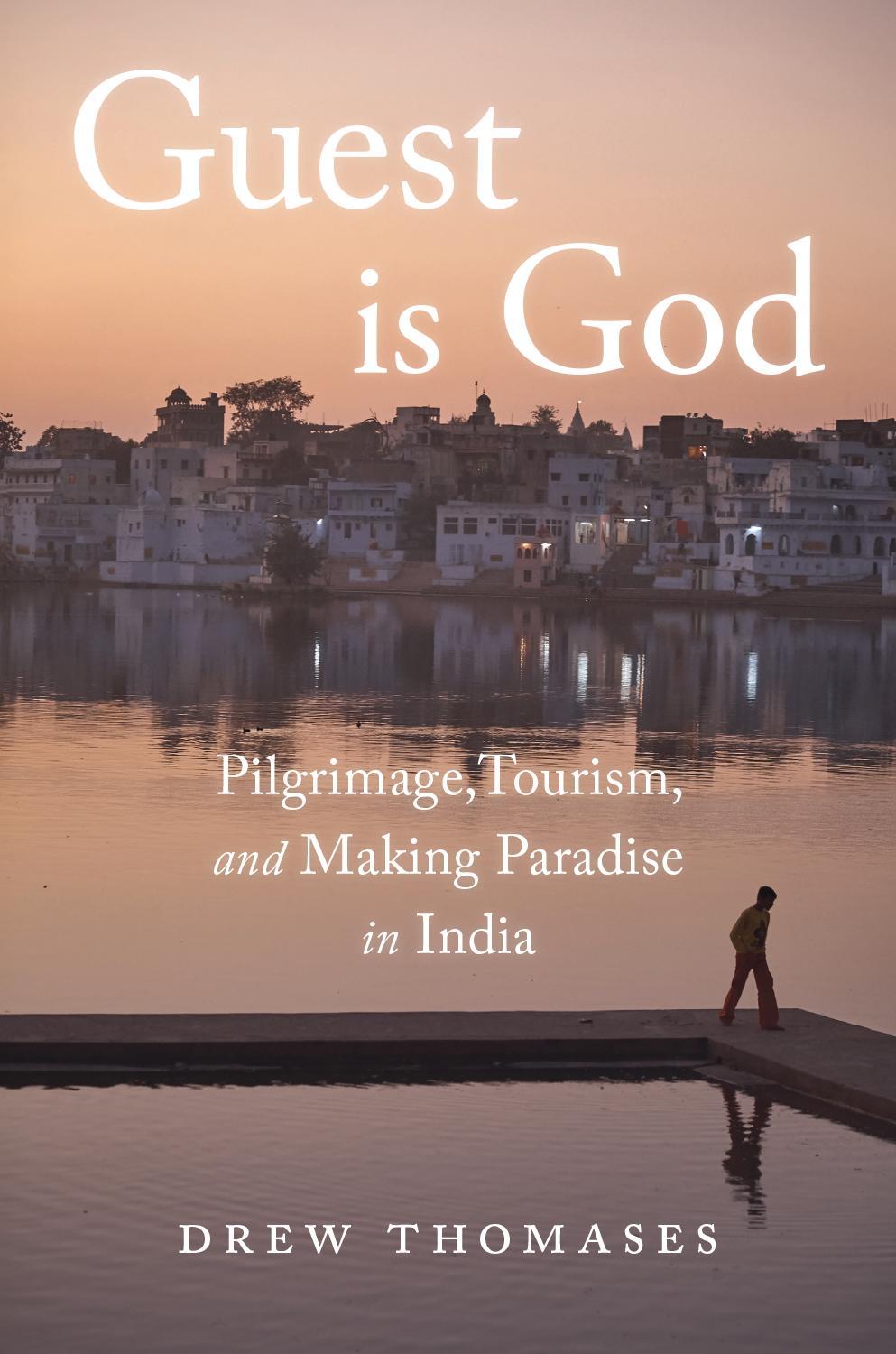

Guest Is God: Pilgrimage, Tourism, and Making Paradise in India. Drew Thomases, Oxford University Press (2019). © Oxford University Press.

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780190883553.001.0001

The neem tree is no worse than the sandalwood Nor is the town of Pushkar worse than London.

February 10

After a long day of wandering around the lake and its surrounding temples, I returned to my room and opened my computer. Before committing myself to writing the day’s fieldnotes, I went straight to Facebook. Even there, my research followed me like a hungry street dog; someone from Pushkar, a brahman and restaurant owner, shared a picture of the town. Taken at sunset, the picture showed the waterfront, ghats, and nearby buildings all blanketed in a warm and orangey glow. Temple to the left. Mosque in the back. Arched windows and doorways on all sides. In addition to the thousand words told by the picture, my friend captioned two more: “our heaven.”

November 20

Nick and I sat at the hotel’s rooftop restaurant as the day’s dust became visible in the refracted light of the setting sun. He was eating chana masala while I polished off my pizza. Hemant, the hotel’s owner, joined us too. We chatted about the fast-approaching camel fair, which had brought Nick to Pushkar for the first time, and which inevitably filled every bed in every hotel. Hemant was visibly excited, not just because of the business but because of the opportunity to make new friends from all over: “I really love that I live here, and that so many people from all over the world come to this one place.” He sighed and said, “For me, Pushkar is paradise.”

Pushkar is a Hindu pilgrimage town in the northwestern state of Rajasthan, India, whose population of roughly 20,000 sees an influx of two million visitors each year. The town’s fame comes from Brahma, the creator god, who eons ago established Pushkar as his home by making a lake in the desert and

performing a sacrifice there. So, while pilgrims visit for a host of reasons— seeking the favor of the gods for things like a successful marriage, good grades on an exam, the birth of a son, etc.—most make sure to bathe in the holy lake and visit the Brahma temple, the latter regarded as the only temple dedicated to the creator god in the known universe.2 Since the 1970s, Pushkar has also received considerable attention from the international tourist community, a group that, early on, was composed largely of hippies and backpackers, but now includes visitors from a wide spectrum of social positions and religious affiliations. Tourists, too, come with different goals in mind, from seeing the lake and experiencing the annual camel fair to doing drugs and taking in the peace of a small-town setting.

Thus, it is perhaps a platitude—if a true one—to say that Pushkar is many things to many people. But the most pervasive discourse surrounding the town claims Pushkar to be one thing in particular: paradise. Call it what you will—heaven, paradise, or “no worse than London”—in the eyes of many people who call it home, Pushkar is a remarkable place. And yet, even heaven needs some upkeep. That is, paradise cannot exist without a concerted effort to make it so, and thus on a daily basis the town’s locals, and especially those engaged in pilgrimage and tourism, work to make Pushkar paradise. This book explores the massive enterprise of building heaven on earth, and how the articulation of sacred space necessarily works alongside economic changes brought on by tourism and globalization. As such, I not only attend to how tourism affects everyday life in Pushkar but also to how Hindu ideas determine the nature of tourism there; the goal, then, is to show how religion and tourism can be mutually constitutive.

It is precisely within this mutually constitutive realm of religion and travel that the process of “sacred making” happens, where developments in (and agents of) tourism draw and redraw, over and over again, the perimeters of paradise. Said differently, the criteria for what counts as “paradise” have shifted together with the changing economy. And as this takes place—as paradise is made and remade in a globalized world—Pushkar’s type of Hinduism is affected, too. Hinduism here possesses a kind of fluctuating scope, at times focused on Pushkar and the uniqueness of its sacred space, at other times expanding to a more panoramic perspective. This book examines the ways in which Pushkar locals work to incorporate both of these perspectives, claiming allegiances to their home and community while making inroads to a vision of human belonging that attempts to embrace all.

The Lay of the Land

It is important to remember, as Clifford Geertz has famously stated, that “the locus of study is not the object of study. Anthropologists don’t study villages (tribes, towns, neighborhoods . . . ); they study in villages.”3 Working from that premise, this book does not examine a town called Pushkar but rather a discourse about Pushkar, by which I mean a constellation of “ideas, attitudes, courses of actions, beliefs and practices” that constructs both “subjects and the worlds of which they speak.”4 The discourse in question is that of making Pushkar paradise, the constitutive parts of which include but are not limited to beliefs about Hindu universalism and how its principles incorporate people from outside of the Hindu fold, ritual repertoires that brahmans perform on behalf of their clients in order to propitiate the gods, mythic tales that boast of Pushkar’s greatness printed in five-rupee pamphlets or narrated by priests at the lake, environmental action taken up by locals worried about lake pollution, and guided tours designed to promote the kind of atmosphere where people from around the world can feel as if they belong. As such, this is less a study about the place in which these ideas and activities are situated and more about the people who think and do them.

At the same time, the people whose lives and words feature in the following pages do not represent all of Pushkar’s population. The project of making Pushkar paradise is pursued especially within the axis of tourism and pilgrimage, and so I tend to engage with the people who labor in those realms.5 These are shopkeepers, hotel owners and staff, restaurant owners, waiters, cooks, camel safari personnel, taxi drivers, priests, and tour guides. With the exception of the latter two categories, which are dominated by brahmans, these other groups are made up of people from a fairly large range of castes. In terms of gender, however, the ratio is decidedly unbalanced. Women do have a presence in the public sphere, as store clerks and pilgrims most commonly, but men conduct the vast majority of business related to tourism. This is not to say that I did not speak to women. Over the years, I have been welcomed into a number of homes, and in those instances when I was folded into the family6 I was able to speak with women quite freely and on a vast range of topics related to my research. In other, less familial settings, conversations were often circumscribed or cut short by Rajasthan’s conservative gender relations and expectations.

Overall, I found that the people who invested their time and effort most explicitly in the idea of Pushkar being a heavenly place were priests and

tour guides. It’s worth noting that locals often use the English word priest, a capacious term which includes both people whose primary job involves providing ritual services (pujas) for pilgrims or tourists at the banks of Pushkar lake (called pandas), as well as those who manage and oversee temples (called pujaris). Throughout the book, I use priest both because it is commonly used and in order to encompass the variety that Hindi offers. Moreover, whether pilgrimage priest or temple priest, they all come from the brahman caste—for many of them, the only designation of real importance. Within the category of brahman, most of my collaborators were from the Parashar subcaste; they constitute Pushkar’s most influential brahman group, both as leaders of the town’s most prominent Hindu organization— the Pushkar Priest Association Trust7 and as those who work on some of the lake’s very best real estate.8 Parashars also make up the majority of the town’s tour guides. And as with priests, brahman guides identify more with their caste status than their occupation. The Parashars whom I called “guides” would consistently remind me that they were not, in fact, guides, but “brahmans who do guiding work.” Throughout the book, I continue to use the term guide, knowing well that some would refuse—or at least contextualize—such a designation, but also recognizing the need to differentiate clearly between various occupations.9

Brahmans, needless to say, occupy a privileged position within India’s caste hierarchy, a convention whose effects not only determine Hindu conceptions of ritual purity but also lead to uneven access to education, employment, and power. In an article published in 1990, Khushwant Singh discusses the changing and increasingly disproportionate employment of brahmans: “Under the British, they had 3%—fractionally less than the proportion of their 3.5% of the population. Today . . . the Brahmin community of India holds between 36% to 63% of all the plum jobs available in the country.”10 This kind of incongruity has lessened alongside the relative successes of India’s reservation policy over the past 25 years, but Singh’s statement still largely holds true. Brahmans very much remain part of an elite class across the subcontinent.

Interestingly, brahmans’ disproportional representation in positions of government seems—at least in part—to echo a similar situation in Hindu studies, a field where brahmans receive a great deal of attention despite being such a small minority.11 There are, no doubt, specific and non-nefarious reasons for this scholarly orientation: textually, brahmans have long exerted enormous authority over the Sanskrit literary canon; anthropologically,

much of modern Hindu practice—in which temple-going and the worship of images are so central—remains inextricably tied to the priesthood. In this sense, my work in Pushkar follows suit. But what makes Pushkar a particularly interesting case study with regard to caste is that its brahman population is not such a small minority. Throughout my fieldwork, I consistently found the town’s priestly presence, with so many brahmans in such a tiny place, to be at odds with India’s caste demography. Government censuses have not tallied the number of brahmans, or any other specific caste community, since 1931. Local reports nevertheless estimate the town to be around 30%–50% brahman—and to me, at least, this seems possible.12 Again, these numbers may not represent the absolute, unequivocal, Brahma-given truth, but they do make a case for Pushkar being a pilgrimage town where brahmans dominate not only in power and authority but in numbers as well.

Pilgrimage, Tourism, and Religion

The field of pilgrimage studies has become somewhat of a minor industry for those interested in the religions of South Asia.13 This is particularly true of ethnographic literature, where pilgrimage offers a wide range of analytical possibilities: it demonstrates how religion and ritual are tied inextricably to techniques of the body14; it amplifies and transforms everyday social formation, in which journeyers’ identities—like those of gender, religion, and caste—can slide in and out of place15; it provides a venue for devotees to express their religious hopes and expectations, whether they be mundane or otherworldly16; and finally, it helps to establish and reinforce sacred geographies.17

But despite these plural interpretive angles, only recently have studies emerged that offer a sustained analysis of how pilgrimage, pilgrimage places, and the people who live in those places have been shaped by the tourism industry.18 This is partly a matter of chronology; it has only been in the last twenty or so years that tourism in India has proven to be an indelible and enduring feature of pilgrimage. The other reason, I suspect, is equally simple though in a different way: people generally do not like tourists. In places across the world, tourists are often perceived as an anonymous group of people passing through, mindlessly consuming, disturbing the peace, and then moving on. It is easy to dislike such faceless travelers. But when in the position of a tourist, it can be hard to convince yourself, never mind

others, that you aren’t one; all the more so if you are an anthropologist. One can easily imagine how, for anthropologists of religion in India, people who have spent years learning a language and studying and who want to be recognized for their efforts, doing fieldwork in a tourist town (and therefore being “misrepresented” as a tourist) can be extremely ungratifying. In a similar vein, tourist towns get in the way of some of the more old-timey and masochistic impulses of fieldwork. I didn’t jot down my daily thoughts by oil lamp as sweat dripped from my nose onto the pages of a decomposing field journal; I had electricity, air conditioning, and Internet. I also had warm showers, and sometimes-fabulous falafel. Anyway, there remain certain tendencies in South Asian studies (and in graduate school, especially) to think of ethnographic pain as pleasure, and creature comforts as somehow not right. As long as these tendencies hold, tourism in India will continue to be understudied.

Outside of South Asia, there is a more substantial body of scholarship on pilgrimage and tourism. The literature can be roughly divided into two groups. Inaugurated by Victor and Edith Turner’s Image and Pilgrimage in Christian Culture, the first group focuses on the structural similarities between pilgrimage and tourism.19 The debate tends to gravitate toward a typology of these two central identities—pilgrims and tourists—and sets out to determine whether the two exist on a continuum, are starkly different, or are one and the same.20 The second group, however, downplays the search for a perfect typology of agents and seeks instead to explore the broad interface of pilgrimage and tourism “on the ground.” It is to this group and its attendant issues that we turn.

When scholars approach the interaction of pilgrimage and tourism, it is often in the language of negative “impact.”21 This perspective is not inherently problematic but, in the case of religion, tends to imply the profaning of a once sacred site.22 Take, for example, the work of Erik Cohen, a major figure in tourism studies and one who sees tourism and pilgrimage as “both closely related and diametrically opposed modalities of conduct.”23 Their opposition, Cohen claims, is based on the idea that whereas pilgrimage entails a sacred search toward the center of one’s religious life, tourism is a secular quest in search of the other.24 Given this distinction, tourism’s impact on a religious site or pilgrimage center is “generally a secularizing one—a weakening of the local adherence to religion and of the belief in the sacredness and efficacy of holy places, rituals, and customs.”25 So, according to Cohen, religion is somehow compromised by the emergence of tourism.

Pushkar, with its incredibly palpable atmosphere of religiosity as well as its ever-increasing popularity as a Hindu pilgrimage site, serves as an obvious counterexample to this supposed secularization. More importantly, Cohen’s argument implies a layering of dichotomies that is equally common and misleading: religion becomes purity, and tourism becomes danger.26 In such a formulation, tourism assumes the role of corrupting force; religion remains something pure, and yet always subject to outside defilement. It is this supposedly diametrical opposition that (as we will see in future chapters) makes tourists and outsiders so wary of priests who make money while simultaneously promoting ideals of religious harmony.

But as Russell McCutcheon reminds us, religion cannot be, and has never been, some “private affair” held entirely apart from the effects of historical, social, or economic change.27 And indeed, metaphors number aplenty on how we might think about the relationship between religion and these other spheres of influence. Are they like a rope, woven of many threads? Tiles, imbricated? Bricks, bound with mortar? For my part, I prefer a botanical metaphor. Picture this: a thicket of trees with branches intertwined. In places, the trees are separate and distinct—call them “religion,” “politics,” “economics,” etc.—but in other places the branches grow completely together, the space between them erased. Botanists have a complicated word for this growing together, “inosculation,” but the image is clear: trees can simultaneously have their own identities and become indistinguishable from others.28 In this model, religion is neither fully reduced to something like an economic scheme or a political tool, nor is it some pristine experience untouched by the outside world. Thus, the interface of religion and tourism cannot find honest representation in a model of opposition, but in one of inosculation and co-production. And we must redouble our efforts in rejecting the idea that such a growing together is a bad thing.

Sacred Making

Given the inosculation of religion and tourism, the devotional and the economical, how does this relationship effect Pushkar’s status as a “sacred” place? Scholars in the discipline of religious studies have long grappled with the idea of “the sacred”—its substance, its salience—but no consensus is waiting in the wings.29 Among those involved in the study of India, one of the most vocal opponents of “the sacred” is William Sax: “People still

write about Hinduism in terms of the hackneyed dualities of sacred and profane, mind and body, matter and spirit, and so forth, hardly stopping to consider that these Cartesianisms are historically determined and culturally specific.”30 Following the “ethnosociological” method of McKim Marriott, Sax prefers to think about Hindu pilgrimage through Indian categories. For my work too, Indian vocabulary and categories serve an undeniably important purpose: they help to reflect with greatest accuracy and greatest adherence to local values the context in which particular topics are discussed.

At the same time, I also see in Sax’s approach a possible amputation of Indian studies from the broader field of religion. We prevent ourselves from having meaningful conversations with scholars of different traditions or regions if we see the cultural worlds in which we work as totally alien to one another. And in more ways than one, Pushkar is itself testament to the fact that “Indian categories” are increasingly shaped by the people, languages, and discourses that bounce across the globalized world. For example, locals themselves call Pushkar a “holy place,” sometimes using the Hindi translation pavitra sthan, but more often than not relying on the English.31 So does this make the English phrase “holy place” an “Indian category”? Maybe. Or maybe it is harder and harder—and in some cases, less useful—to confine certain ideas to a bounded geography or tradition.

Sax is right, though: we should be wary of the “hackneyed dualities” that structure Western thinking. “Sacred” and “profane” represent one such duality, and it can be used to essentialize the relationship between pilgrimage and tourism. But, to me at least, the primary problem here is not the duality itself but the fact that “sacred” and “profane” are sometimes taken to be inherent qualities, existing outside of history or politics and not subject to change. This is where Jonathan Z. Smith comes to the rescue, explaining that “the sacred” does not simply exist in a vacuum, but is made:

We do well to remember that long before “the Sacred” appeared in discourse as a substantive (a usage that does not antedate Durkheim), it was primarily employed in verbal forms, most especially with the sense of making an individual a king or bishop (as in the obsolete English verbs to sacrate or to sacre), or in the adjectival forms denoting the result of the process of sacration. Ritual is not an expression of or a response to “the Sacred”; rather, someone or something is made sacred by ritual (the primary sense of sacrificium).32

For Smith, ritual is not simply a series of repetitious actions but is “first and foremost, a mode of paying attention.”33 As such, something like a temple or a ritual object or a pilgrimage place only becomes sacred when it has “attention focused on it in a highly marked way.”34 This means, then, that instead of trying to identify “sacred spaces” as if they simply are, we should look to the actions and affective orientations that can make the sacred. The ritual component behind the making of sacred space echoes my own observations from fieldwork, and especially so when it comes to the topic of locals cleaning up Pushkar lake, which I will explore in the second chapter.

But beyond ritual, we must also see in the creation of sacred space factors related to power. David Chidester and Edward Linenthal are particularly insightful on the issue:

Sacred space is inevitably contested space, a site of negotiated contests over the legitimate ownership of sacred symbols . . . Power is asserted and resisted in any production of space, and especially in the production of sacred space. Since no sacred space is merely “given” in the world, its ownership will always be at stake. In this respect, a sacred space is not merely discovered, or founded, or constructed; it is claimed, owned, and operated by people advancing specific interests.35

Here, Chidester and Linenthal help to support and give texture to one of this book’s most basic premises, namely, that Pushkar becomes paradise not because of some timeless truth, but through the actions of historically situated people who negotiate its terms, articulate its borders, and claim ownership over it.36 Thus if we were to attribute Pushkar’s popularity as a pilgrimage place to what James Preston calls a “spiritual magnetism,” we would need to understand that magnetic or attractive quality in terms of particular powers and interests.37 So while locals may consider their town a “holy place”— and may pin that holiness on Brahma and his sacrifice, or the lake’s magical powers—I want to emphasize the extent to which the idea of a holy or sacred Pushkar is also shaped and produced through the tourism industry, its economic incentives, and the people whose lives depend on such an economy. Most of this book is about those people: the priests and guides and hotel owners and shopkeepers who together participate in the project of sacred making. They do it with rituals, stories, sayings, recitations, and vibrations, among many other things. We will discuss these issues later, both in the introduction and throughout the coming chapters. For now, however, we will

briefly explore the broader interests behind Pushkar’s still-growing popularity, some of which are not local at all but are controlled by much larger institutional bodies responsible for India’s economy and infrastructure.

As Ian Reader explains, the creation of pilgrimage places is often “facilitated by powerful commercial interests instrumental in providing the publicity” that garners attention from a wide audience.38 Said differently, before a pilgrimage place can be a pilgrimage place, people need to actually go there. And before going there, people need to know about it and have the infrastructure to get there. Pushkar has attracted Rajasthani pilgrims for hundreds of years, but its popularity on the national and international stage is more recent, with a particularly substantial jump in tourism over the past thirty years. Much of this jump is due to the effects of India’s liberalization, which entailed a series of reform policies that the federal government put forward in order to open their economy to the global market. These policies, which were initiated in the mid-1980s and further advanced in 1991, led to reduced tariffs on foreign goods, the growth of the private sector, and increased wealth within the Indian middle class.39

Domestically, increased GDP and spending capacity on the part of the middle class meant Indians were now increasingly able and inclined to travel. Internationally, foreign interest and investment spurred the Indian government to recognize tourism as one of the major paths toward the country’s economic development. As part of this recognition, the state government of Rajasthan initiated a number of infrastructural road, rail, electric, and water projects throughout the 1990s which, among other things, helped to make the state more manageable for visitors.40 In 2002, the Indian Ministry of Tourism launched an international branding campaign called “Incredible !ndia,” which has tirelessly promoted the romantic appeal of Rajasthan as a land of mustaches, turbans, camels, white dunes, and brown bodies. As for Pushkar, geographic logistics make it a convenient destination. Because the town is only a short bus trip from Jaipur, which along with Agra and Delhi forms the “Golden Triangle of Tourism,” Pushkar offers an easy experience of small-town India for middle-to-upper-class tourists on packaged tours who don’t want to stray too far off the beaten path. Backpackers come too, and although they tend to have less money than their package-tour counterparts, they also stay for much longer. These are travelers who tend to determine their itineraries by the seat of their pants, relying on travel advice from books like Lonely Planet or from word-of-mouth recommendations. But regardless of tourists’ differing dispositions, we can see from the significant increase in

the number of internationals coming to Pushkar over the years—with 8,820 in 1985 compared to 63,312 in 2005—that the triumph of Pushkar’s “spiritual magnetism” seems to emerge alongside, and entangled with, broader economic gains brought on by liberalization.41 These are things that grew together. And recognizing that such “spiritual magnetism” is subject to change, we can now look to Pushkar in the beginning of its experiments with tourism, when things were quite different than they are today.

The Growing Pains of Tourism

A small international presence in Pushkar preceded India’s liberalization by some decades, beginning in the early 1970s with an influx of young, backpacking, and hippie types. Staying in Pushkar would have been a very different beast back then, because the town had only caste-based rest houses meant for pilgrims (dharamshalas), and possessed none of the conveniences now associated with tourism, such as banana pancakes, bottled water, and toilet paper. But changes came quickly. As witnesses to the new and peculiar trend of wandering hippies in the main bazaar, a few of the more entrepreneurial locals opened their homes to outsiders. These homes became the town’s first “guesthouses,” which now, decades later, unendingly line Pushkar’s streets and alleys.42 With ever more foreigners, their pockets bulging from favorable exchange rates, cash flowed into the town. This led to further investment as locals set up more hotels and restaurants and juice stands and clothing stores and shops selling trinkets, tchotchkes, and knickknacks.

As might be expected, problems between locals and tourists began to surface from almost the very beginning of their relationship. In 1979, local scholar Janardan Sharma penned an article in the Hindi magazine Dharmyug, titled “Devanagari Pushkar men Hippie” (“Hippies in Pushkar, a Town of the Gods”). In it, he bitterly critiques the town’s hippie presence: “You can see these whimsical tourists everywhere, in Pushkar’s alleys, bazaars, houses, ghats, hotels, fields, and cremation grounds; they relax and sing, swim in the lake, smoke marijuana and hash, make noises, laugh, and are a nuisance—all of this they do naked or half-naked.”43 Sharma then laments the proliferation of hotels and drug use, both of which stand to threaten the “mental peace” that the town holds so dear. And he ends on a particularly sour note, wondering “how much more will the change brought

on by Western culture damage the town’s spiritual nature.”44 In some ways, Sharma’s elegy really does ring true; Pushkar has undoubtedly changed. The town’s tourism economy is omnipresent, and joining the small contingent of half-naked hippies are now thousands of other visitors from a hugely diverse background. Of course, whether such changes damage the town’s “spiritual nature” is a matter of opinion. But I hope to show throughout the book that the very content of Pushkar’s “spiritual nature” has itself changed along with the town. That is, Pushkar’s being paradise is increasingly contingent upon, rather than in spite of, tourism. Nevertheless, by bringing up drugs and hotels in particular, Sharma highlights the two topics that can, even today, still elicit animosity.

Drugs came to pose a material threat to Pushkar in the early 1980s. Beyond marijuana, which was in all likelihood only culpable for inspiring hippies to frolic in the nude, heroin was a much more serious problem. For reasons related largely to geography and agriculture, India was brought into the network of international drug trafficking at that time.45 The subcontinent was never meant to be the final destination for these drugs—just a stop on the way to other locales—but some never left. And heroin was one in particular that stayed beyond its welcome, making some rich and many more addicted across the country. Pushkar was not unique in this sense, though tourism provided an especially robust and constantly-refreshing market for the drug trade. Rick, a grey-haired hippie from Canada, referred to Pushkar in the 1980s as a place famous “for the wrong reasons.” Local police got more serious about cracking down on dealers and putting addicts in hospitals after 1985, though even in 1988 a report from The Times of India referred to Pushkar as a “center for drug traffic.”46 According to the article,

Transactions worth lakhs of rupees take place at the time of fairs and festivals. Even the “pandas” are engaged in the trade. If a senior police officer is to be believed, the number of those involved in deals, directly or indirectly, is around 500 . . . Smack has been the most sought after, followed by charas [hash] and ganja which are in demand by foreigners . . . The flourishing trade has led many youths to drug addiction, and drugs have claimed the lives of four youths during the past two years.47

By all recent reports, and in my own observation, heroin use and abuse has steadily decreased since the 1980s, and is no longer a problem in Pushkar. Nevertheless, these memories are sufficiently fresh that many of the older