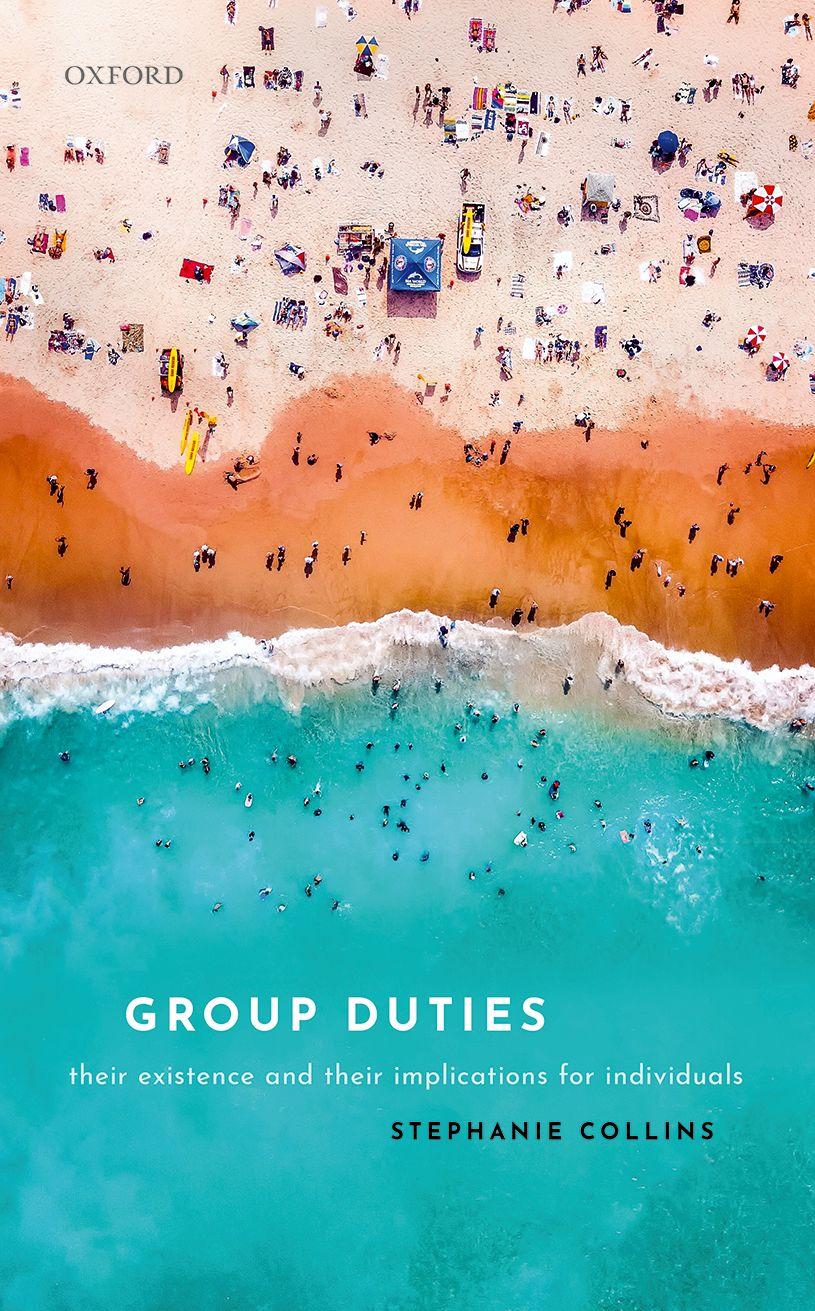

GroupDuties

StephanieCollins

GreatClarendonStreet,Oxford,OX26DP, UnitedKingdom

OxfordUniversityPressisadepartmentoftheUniversityofOxford. ItfurtherstheUniversity’sobjectiveofexcellenceinresearch,scholarship, andeducationbypublishingworldwide.Oxfordisaregisteredtrademarkof OxfordUniversityPressintheUKandincertainothercountries

©StephanieCollins2019

Themoralrightsoftheauthorhavebeenasserted

FirstEditionpublishedin2019

Impression:1

Allrightsreserved.Nopartofthispublicationmaybereproduced,storedin aretrievalsystem,ortransmitted,inanyformorbyanymeans,withoutthe priorpermissioninwritingofOxfordUniversityPress,orasexpresslypermitted bylaw,bylicenceorundertermsagreedwiththeappropriatereprographics rightsorganization.Enquiriesconcerningreproductionoutsidethescopeofthe aboveshouldbesenttotheRightsDepartment,OxfordUniversityPress,atthe addressabove

Youmustnotcirculatethisworkinanyotherform andyoumustimposethissameconditiononanyacquirer

PublishedintheUnitedStatesofAmericabyOxfordUniversityPress 198MadisonAvenue,NewYork,NY10016,UnitedStatesofAmerica

BritishLibraryCataloguinginPublicationData

Dataavailable

LibraryofCongressControlNumber:2019934004

ISBN978–0–19–884027–5

Printedandboundby CPIGroup(UK)Ltd,Croydon,CR04YY

LinkstothirdpartywebsitesareprovidedbyOxfordingoodfaithand forinformationonly.Oxforddisclaimsanyresponsibilityforthematerials containedinanythirdpartywebsitereferencedinthiswork.

Preface

I firstgotannoyedbygroupdutiesin2009.IwasdoingaMasterof PublicPolicycourseattheUniversityofAuckland,forwhichItook AnitaLacey’sexcellentclass ‘GlobalGovernance’.Eachweekwewere presentedwithanewcrisis:globalization,sovereignty,poverty,security, andsoon.Obviously,theproblemswerevastandcomplex.Ateachturn, theentitieschargedwithsolvingtheproblemseitherseemedincapable ofsolvingthem(e.g.whenweconsideredthedevelopmentpoliciesofa particularstate,ortheimpotentremonstrationsoftheUNSecurity Council)orseemed(tome)tobenotthekindsofthingsthatcould eventrytosolveanything(e.g.whenweponderedwhattheinternational communitymightdoaboutethniccleansing,orhowtheBrettonWoods Institutionsshouldtogetherapproachloanconditionality).Ipersistently feltthattheaspirationsoftheworldwerebeingthrust byscholarsand practitionersalike intothehandsofthewrongsortsofentities:diffuse andamorphous ‘frameworksofgovernance ’ or ‘communitiesofpractice’,ratherthanspecificandmaterial ‘agentsofgovernment’.Yet,atthe globallevel,whatchoicedoscholarsandpractitionershave?

ItturnedoutIwasaphilosopherbydisposition,soIreturnedto Philosophyandhavesinceintermittentlyworkedonthequestion:when wewanttodemandthatourworldgetsbetter,towhatsortsofgroupmay weaddressthatdemand?Isittooambitioustosaythat ‘humanity’ shouldsolveglobalills?Isittooreductivetosayit’salldownto individuals?Thisbookismyattempttoaddressthosequestions.Unfortunately,thebookdoesn’tcomeclosetobringingthephilosophical rubbertobearonthepoliticalroad.ButIhopeitprovidestheconceptual toolstoatleastpartlyguideourpoliticalthought,talk,andpractice.

Asitturnsout,it is tooambitioustosaythathumanityshouldsolve globalills.Andit is tooreductivetosayit’salldowntoindividuals. Instead,Isuggest,weneedamixedapproach.Theapproachcomesin threeparts,whichtogethermakeupmyTripartiteModelofgroup duties.First,therearegroupsthataremere combinations collections ofagentsthatdon’thaveanygoalsordecision-makingproceduresin common.Thesegroupscannotbearmoralduties.Instead,whenweare

temptedtoattributedutiestothem,weshouldre-castthepurportedduty asaseriesofduties onebornebyeachagentinthecombination.Each dutydemandsitsbearerto ‘I-reason’:roughly,todothebesttheycan, givenwhatevertheyhappentobelievetheotherswilldo.Second,there aregroupswhosememberssharegoalsbutlackdecision-makingprocedures.Theseare coalitions.Coalitionsalsocannotbearduties,buttheir allegeddutiesshouldbereplacedwithmembers’ severaldutiesto ‘ wereason ’:roughly,todoone’spartinaparticulargrouppatternofactions, onthepresumptionthatotherswilldolikewise.Third,and finally, collectives havegroup-levelproceduresformakingdecisions.Theycan bearduties.Collectives’ dutiesimplydutiesforcollectives’ membersto usetheirroleinthecollectivewithaviewtothecollectivedoingitsduty.

Inrecentyears,I’vehadnumerousheatedexchangesaboutthese issues.It’simpossibletonameeveryonewho’shelpedmebyarguing withme,sinceIcan’tremembereveryseminarroomandpubinwhich theseideashavecomeup.Somepeoplehavebeenthankedinthejournal articlesandbookchaptersassociatedwiththisresearch,giveninthe ReferenceListinthisvolume.ButI’dliketosingleoutsomeagents individualandcollective formentionhere.

First,theSchoolofPhilosophyattheAustralianNationalUniversity, thePoliticsDepartment(andparticularlytheManchesterCentrefor PoliticalTheory)attheUniversityofManchester,andtheInstitutefor ReligionandCriticalInquiryattheAustralianCatholicUniversityhave successivelyprovidedsupportiveandstimulatingintellectualhomes. Mycolleaguesateachofthoseinstitutionshavebeentremendous.

IalsothanktheMindAssociation,whoseawardofaResearchFellowshipgavemethesixmonthsinwhichIwrotethe firstdraft. IworkshoppedandrevisedthatdraftwhileaCampusVisitoratthe AustralianNationalUniversity,undertheauspicesofNicSouthwood’ s AustralianResearchCouncilFutureFellowshipFT160100409 ‘Feasibility inPolitics:TakingAccountofGroupsandInstitutions’.Icompleted furtherrevisionswhileaResearchVisitingProfessorattheUniversityof ViennawithHerlindePauer-Studer,forwhichthisbookhasreceived fundingfromtheEuropeanResearchCouncil(ERC)undertheEuropean Union’sHorizon2020researchandinnovationprogramme(grant agreementNo740922).

Iamgratefulforthepermissiontoincludeextended,revised,and updateddiscussionsfromapreviouspublicationinthisbook.The

discussionofmembershipdutiesinChapter7isdrawnfromCollins, Stephanie, ‘DutiesofGroupAgentsandGroupMembers’ , Journalof SocialPhilosophy,Volume48,Issue1,pp.38–57,Copyright©2017, JohnWileyandSons,doi:10.1111/josp.12181.

IthankJelenaBelić andZoltanMiklosifororganizingatwo-day manuscriptworkshopfundedandhostedbytheCentralEuropean University,andChristianBarryfororganizingatwo-daymanuscript workshopfundedandhostedbytheAustralianNationalUniversity.For readingchapters(orindeedthefulldraft)andgivingcommentariesat thoseworkshops,IthankChristianBarry,JelenaBelić,OlleBlomberg, FrankHindriks,HollyLawford-Smith(twice),ZoltanMiklosi,Avia Pasternak,SimonRippon,NicSouthwood,KaiSpiekermann,William Tuckwell,andBillWringe.OthervaluableparticipantsincludedRenée JorgensenBolinger,MaxFedoseev,JasperHedges,JamesEdgarLim, DuncanMartin,HerlindePauer-Studer,AnnePolkamp,andShang LongYeo.ThefulldraftwasalsoreadanddissectedbyBobGoodin, NielsdeHaan,andtwoanonymousreadersforOxfordUniversityPress, whoturnedouttobeDavidKillorenandMarionSmiley.

Mythinkingontheseissueshasbeenshapedbyconversationswith manyotherpeople,including(butnotlimitedto)ElizabethAshford, RobertAudi,GunnarBjörnsson,SaraRachelChant,GarrettCullity, AlexanderDietz,ToniErskine,DavidEstlund,KendyHess,Onni Hirvonen,SädeHormio,ChristineHobden,ViolettaIgneski,Tracy Isaacs,ElizabethKahn,ArtoLaitinen,ChristianList,DavidMiller,Philip Pettit,FelixPinkert,Paul-MikhailPodosky,RichardRowland,David P.Schweikard,AnneSchwenkenbecher,LeonieSmith,ThomasSmith, AnselmSpindler,andAnnaStilz.Althoughshe’snamedabove,Ishould mentionthatmygreatestintellectualdebtistoHollyLawford-Smith. Ourjointworkoncollectives’ dutieshasgreatlyinformedmyapproach inthisbook eventhoughshedisagreeswithseveralofitsarguments. Finally,mygreatestpersonaldebtistoJonathanFarrell,whosesupport duringtheinitialdevelopmentofthisbookhasstayedwithme throughout.

1 TheTripartiteModel

1.1IntroducingtheTripartiteModel

Wetreatgroupsasiftheyhaveduties.To findevidenceofthis,youjust needtoopenanewspaper.InJanuary2019,aneditorialin TheObserver addresseditsreadersinBritain: ‘Asanation,wemayhavedifferentviews onimmigration,butsurelywecanallagreethatBritainhasamoralduty toprovidesafeharbourtomorepeople fleeingconflicts’ (ObserverEditor 2019).InMarch2017,conservativecommentatorJamesBickertonargued that ‘conservativeshaveaparticulardutytodefendliberal-democratic civilizationfromTrump’sauthoritarianism’ (Bickerton2017).InOctober 2012,theformerUnitedNationsSecretary-GeneralBanKi-moontold anaudienceatDrakeUniversitythat ‘[t]heinternationalcommunity hasamoralresponsibility,apoliticaldutyandahumanitarianobligationtostopthebloodbathand fi ndpeaceforthepeopleofSyria ’ (UNDPI2012).

Suchstatementsarenotreadilyunderstandableasassertingthateach memberoftherelevantgrouphastheduty.EachmemberofBritain cannotensurethatBritainprovidessafeharbour.NoteventhePrime Ministercandothis,ifactingalone.Sothedutytoprovidesafeharbour isnotadutythatanyindividualmemberofBritaincanhave.Likewise, noconservativecandefendtheentiretyofliberal-democraticcivilization fromanyone’spurportedauthoritarianism.Defendingacivilizationis simplynotsomethinganyindividualcando.Civilizationscanbe defendedandupheldonlybythecombinedactionsofmanyindividuals. SoBickerton’sclaimeddutymustbeheldbyconservativesasagroup. Andeachmemberoftheinternationalcommunitycannot,onitsown, findpeaceforthepeopleofSyria.Thisistrueregardlessofwhetherwe takethemembersofthatcommunitytobeindividualsorstates.No singularindividualorstatecanactunilaterallyto findpeaceforthe

peopleofSyria.Itwouldtakecollaborationbetweenmanysuchentities to findpeace.Itwouldseem,then,thatallthreedutiesarebeing attributedtogroups ‘intheirownright’:thedutyisbeingattributedto agroupasasingularentity orperhapstothemembersasaplurality nottoeachofthegroup’smemberstakenseverally.

Thisbookasks:Dosuchattributionsmakeconceptualsense?And whatdoesthatimplyforthegroups’ members?Inparticular:whensuch attributionsdomakesenseandaretrue,whatdothesegroup-heldduties implyaboutthedutiesofthegroup’smembers?Andwhensuchattributionsdonotmakesense,howshouldwecharitablyinterpretsuchtalk? Whatdutiesmightsuchtalkbetakentoimputetothegroup ’smembers? Toanswerthesequestions,weneedamodelthatcantakeindetailsabout thereal-worldgroupstargetedbysuchtalk,andproduceconclusions about(i)whichofthesereal-worldgroups,ifany,canhavedutiesand (ii)whatthesegroups’ duties ortheirinabilitytobearduties imply aboutthedutiesofthegroups ’ members.

Thisbookdevelopsanddefendssuchamodel.Icallitthe ‘Tripartite Model’ ofgroupdutiesbecauseitdividesgroupsintothreefundamental categories.Eachcategoryreceivesdifferentanswerstotheabovequestions.Togeta fl avourofthethreecategor ies,reconsidertheabove examples.

ThedutytoprovidesafeharbourwasattributedtoBritain.In context, ‘Britain’ clearlyreferstotheUK(ratherthanGreatBritain, whichexcludesNorthernIreland).TheUKisahighlyorganizedgroup. Ithasadecision-makingprocedure,whichitoperatesinamore-or-less rationalway.Thisprocedureencompasses(amongstotherthings)the housesofparliament,ministerialdepartments,andjudicialsystem.The UK’sdecision-makingproceduresubsumesthemorespecificprocedures oftheseentities,whichareused,respectively,tocreate,enforce,andapply theUK’slaws.Viatheseprocedures,theUKhasthecapacitytoattendto moralconsiderations evenifitoftenfailstodoso.

TheoutputsoftheUK’soverarchingdecision-makingprocedure andthemorespecificproceduresthatitsubsumes distributeroles amongstmembers,wheretherolesaresufficientforenactingtheUK’ s decisions.Rolesincludethingslike ‘payerofthetoptaxrate’ , ‘motorist whodrivesontheleft ’ , ‘ teacherofthisparticularcurriculum ’ .These areallrolesthataredistributedbytheUK ’ sdecisionprocedure,via itsvarioussub-procedures.Whensuchrolesareenacted,theirbearers

areenactingtheUK’sdecisions.What’smore,eachmemberoftheUKis permitted,bytheUK’sdecision-makingprocedures,tohaveinputsinto theUK’sdecision-makingprocedure whetherthoseinputstaketheform ofvotes,petitions,statementsinparliament,evidencegiventojudges,and soon.TheUKis(whatI’llcall)a collective.

Inthesecondquoteabove,JamesBickertonattributedadutyto conservatives.Importantly,weknowhewasn’taddressingaspecific politicalparty,sincehewasaddressingagroupthatspansatleasttwo countries(theUKandtheUS).Sohewasn’taddressingtheUK’ s ConservativeandUnionistParty which,liketheUK,isacollective. Instead,hewasaddressingthegroupthatincludesallpeoplewhohold certainvalues,goals,andbeliefs.Inparticular,Bickertonimpliesthat eachconservativeholds ‘liberal-democratic-capitalistvalues’,thegoalsof ‘taxcutsandreducedbusinessregulation’,andthebeliefthat ‘ademagoguewithacleardisregardfordemocraticnorms ... isnotanacceptablecandidate’ (Bickerton2017).

Asexplainedabove,Bickertonisnotcharitablyunderstoodassaying that each oftheseindividualconservativesmustdefendliberaldemocraticcivilization.Instead,hewasaddressingthegroupcomprised ofallthosewhosharethesevalues,goals,andbeliefs,andwhoare therebydisposedtointeractwithoneanotherinsuchawaythatthose goalsgetachieved,andthosevaluesgetrespected,inwaysthatare constrainedandguidedbythebeliefs.Thisgrouplacksthekindof group-leveldecision-makingprocedure,andthedistributionofroles forenactinggroupdecisions,thatwe findincollectivessuchasthe UK.Butitsmemberssharegoalsandaredisposedtoactpositively towardsoneanotherinpursuitofthosegoals.Conservativesarea coalition.

Finally,BanKi-moonattributedanobligationtotheinternational community.Thereisdisputeaboutwhat,exactly, ‘theinternational community ’ refersto,withsomecommentatorssuggestingthatitrefers to ‘thewest,ofcourse,nothingmore,nothingless’ (Jacques2006).Butin themouthofBanKi-moon,speakinginhisroleasUNSecretaryGeneral,itismorecharitabletoview ‘theinternationalcommunity’ as referringtothatgroupofpoliticalstatesthatismadeupofmembersof theUN.Tobeclear,then,theinternationalcommunityisagroupwhose membersarealsogroups.(Tobespeci fic,itsmembers states are collectives.)Butit’snotclearthatBanmeant ‘theUN’ whenhesaid

‘theinternationalcommunity’¹ afterall,theUN(whetherGeneral Assembly,SecurityCouncil,oranotherbranch)doesnothavethe authorityto require itsmembersto ‘bringpeacetoSyria’.Let’ sassume thatifhe’dmeant ‘UN’,hewouldhavesaid ‘UN’ .

Instead,Bancanbeinterpretedasattributingadutytothegroupthat iscomposedofallthoseentities(states)thathappenalsotobemembers oftheUN.Hewasnotaddressingthisgroup qua UN.Instead,hewas addressingthisgroupsimplyasacollectionofstates,eachofwhichhas differentvalues,goals,andbeliefs,andeachofwhomcanact outside theUN(though,hemighthavehoped,withtheUN’sblessing)inways relatedtopeaceinSyria.Theinternationalcommunityisneithera collectivenoracoalition.Becausetheinternationalcommunityisneither acollectivenoracoalition,it’ sa combination.

Collectives,coalitions,andcombinationsaretheorganizingcategories oftheTripartiteModel.Inthemostgeneralandabstractterms:collectivesareconstitutedbyagentsthatareunitedunderarationallyoperated group-leveldecision-makingprocedurethathasthepotentialtoattend tomoralconsiderations;coalitionsareconstitutedbyagentswhoeach holdaparticulargoalandaredisposedtoworkwiththeotherstorealize thegoal,whilelackingagroup-leveldecision-makingprocedurethat hasthepotentialtoattendtomoralconsiderations;andcombinations areconstitutedbyanycollectionofagentsthatdonottogetherconstituteeitheracollectiveoracoalition.Thesethreecategoriesofgroup areexhaustiveandmutuallyexclusive.

TheTripartiteModelgivesthefollowingverdicts.First,neithercoalitionsnorcombinationscanhavedutiesintheirownright,thatis,duties thatarenotidenticaltoaconjunctionofmembers’ duties,or(equivalently)dutiesthatarenotmereshorthandforaconjunctionofmembers’ duties.IargueforthisinChapters2and3.Chapter2challengessix argumentsthatpurporttoshowthatcombinationsandcoalitionscan bearduties.Chapter3tacklesthepositivetaskofprovidingargumentsin favouroftheideathattheycannotbearduties.

How,then,shouldwecharitablyinterpretcommentatorssuchas BickertonandBan,whentheyattributedutiestocoalitionsandcombinations?Chapter4arguesthattheyshouldbeunderstoodassayingthat

¹IthankToniErskineforpressingthisinterpretation.

eachmemberoftherelevantgrouphasadutytoactinresponsetothe others, withaviewto defendingliberal-democraticcivilizationorbringingpeacetoSyria.Chapter4givesthese ‘coordinationduties’ aprecise structureandasetofsufficientconditionsontheirexistence.

Coordinationdutiescanbeheldbymembersofbothcoalitionsand combinations.YetChapter5arguesthatcoordinationdutiesoperate differentlyincoalitions,ascomparedwithcombinations.Specifically: whenonehasacoordinationdutyasamemberofacoalition,thatduty demandsthatoneengageinaparticularvariantof ‘we-reasoning ’ , whichIcall ‘coalition-reasoning ’.Bycontrast,whenheldasamember ofacombination,coordinationdutiesdemandthatoneengagein ‘I-reasoning ’.(ThisdistinctiondrawsonBacharach(2006),Tuomela (2007;2013),Sugden(2003),GoldandSugden(2007),andothers.) Thus,theimplicationsof(thelackof)groupdutiesformembersare differentincoalitionsandcombina tions.Thisaffectsnotjusthow themembersshouldreason,butalsohowtheyshouldact.Aswe ’ ll see,itmeanscoordinationdutieshavemorechanceofproducing valuableoutcomeswhentheyareheldbymembersofacoalition thanwhentheyareheldbymembersofacombination(allelsebeing equal).

Chapter6defendsmyaccountofcollectives,whichismorepermissive thanotherprominentaccountsintheliterature.Thatis,it’seasyfora grouptobeacollective.Specifi cally,unlikePeterFrench(1984),Ido notrequirecollectivestohaveunchangingcorporatepolicies;unlike CarolRovane(1998),Idonotrequirecollectivestohaveaunifi ed project;andunlikeChristianListandPhilipPettit(2011),Ipermit dictatorialcollectives,unanimity-basedcollectives,andothercollectivesinwhichthegroup’sattitudesonaparticularissuearedetermined bycertainmembers ’ attitudesonthatissue(solongasthecollective canremainrational).

Chapter6arguesthatcollectivescanhavedutiesintheirownright.So, whenacollectivebearsaduty,itsmembers’ dutiesarenotbestunderstoodascoordinationduties.Instead,whenacollectivebearsaduty,this impliesthateachofitsmembershas(whatIcall)a ‘membershipduty’ . Thesearedutiestoactwithinandbecauseofone’sroleinacollective, withaviewtothecollectivedoingitsduty.InChapter7,Iexplainwhy membershipdutiesfollowfromcollectives’ dutiesandhowmembership

dutiesarestructured.Aswillbecomeclear,they’requitedifferentfrom coordinationduties.²

TheTripartiteModelissummarizedinthefollowingdiagram.The diagramalsoindicateswhichchapterarguesforwhichaspectofthe model.

Is the group to which a duty is being attributed a collective?

COLLECTIVE

The group can bear duties in its own right (Chapter Six). When the group bears a duty, each of its members bears a membership duty (Chapter Seven).

NOT A COLLECTIVE

The group cannot bear duties in its own right (Chapters Two and Three). Under certain conditions, each of its members bears a coordination duty (Chapter Four). Is the group in question a coalition or a combination?

COALITION

When each of the members has a coordination duty, this is a duty to coalition-reason (Chapter Five).

COMBINATION

When each of the members has a coordination duty, this is a duty to I-reason (Chapter Five).

Therestofthisintroductorychapterwill: first,relategroupdutiesto somenearbyphilosophicalissues;second,elaborateonthethreetypesof groupinmoredetail;andthird,explainthescopeofthebook’saims.

1.2NearbyIssues

Philosophershaveaddressedissuescloselyrelatedtogroupduties.But welackacomprehensivetheoreticalframeworkforgroupduties where, by ‘comprehensivetheoreticalframework’,Imeanaframeworkthatcan takeinthefactsabout any groupandproduceanswerstothequestionsof

²Anoteonterminology.Iwillsometimestalkabout ‘members’ andsometimesabout ‘individuals’.Inbothcases,Irefertoagents.Membersareagentswhoconstituteagroup; individualsareagentswhomayormaynotconstituteagroup.Chapter6willarguethat collectivesareagents.So,sometimes,anagentialconstituent member ofagroupwillbe acollective.Forexample,theHouseofCommonsisacollectiveagentthatisamemberof thecollectiveagentthatistheUK.TheHouseofCommonsistreatedasanindividual,when itcomestoconsideringtheimplicationstheUK’sdutieshasforitsmembers.So,ingeneral, ‘individual’ means ‘individualagent’,not ‘individualhuman’ .

(i)whetherthatgroupcanhavedutiesinitsownrightand(ii)whatthat impliesaboutthedutiesofthegroup ’smembers.

Toseethatphilosophershaveaddressedrelatedissues,ithelpsto distinguishdutyfromresponsibility.Thoseworkingoncollectivemoralityhaveaddressedresponsibilityfarmoreextensivelythantheyhave addressedduty. ‘Responsibility’ isanotoriouslyambiguousandmultifacetedconcept(Hart1968).Wecandistinguishatleastthreesensesof group-levelresponsibility-for-an-outcome:causal,moralretrospective, andmoralprospective(Collinsforthcominga).Thelastoftheseiswhat Imeanby ‘duty’

Causalresponsibilityexistswhenonethingimpactsorinfluences another.Thecausalresponsibilityofgroupshasbeeninvestigatedextensivelyinthehugeandlong-runningsocialscientificdebatebetween methodologicalindividualistsandholists(cornerstonesofwhichare Durkheim[1898]1994;Weber1922;Hayek1942;Elster1982;Kincaid 1986).Withinthatdebate,theprimaryquestioniswhethergroupsare eliminablefromourexplanationsaboutwhatcauseswhatwithinthe socialworld.Thisdebateobviouslybearsupongroupduties.Inparticular,ifgroups ’ causalpowerscannotbeeliminatedfromoursocial ontology,thenthisgivesusreasontopositgroupsasdistinctentities. Wearethenonestepclosertoattributingdutiestogroups,sincegroups’ existenceasdistinctentitiesisplausiblynecessaryforthemtohaveduties intheirownright.Butgroups’ distinctexistenceisnotsuf ficientfortheir havingdutiesintheirownright;causalresponsibilitydoesnotentaila capacitytobearduties.Ontheotherhand,itmightbethatgroups’ duties mustbepositedwithinourmoraltheory,thoughtheircausalpowerscan beeliminatedfromoursocialscientificexplanations.Groupswouldthen bedistinctentities,whoseexistencemustbepositedformoralpurposes (forexample,becausetheirdutiesjustifyorgroundindividuals’ duties) butwheregroupsarenotpositedbecauseoftheircausalpowers.So thecausal-explanatorysocial-scienti ficquestionisnottheoneI’ mconcernedwith.

Thereisanothersenseofgroupresponsibility,whichhasreceivedless attentionthancausalresponsibility,butstillmorethanduties.Thisis moralretrospectiveresponsibility.Thisisthekindofresponsibilityat issueindebatesaboutblame,freewill,answerability,andaccountability. Itissometimescalledthe ‘basicdesert’ senseofresponsibility(Pereboom 2001)andisoftenusedinterchangeablywith ‘blameworthiness’ (Smiley

2010).Ilabelthistypeofresponsibility ‘moralretrospective’,tomark thatitisessentiallyconcernedwitheventsthathavealreadyhappened (unlikemoralprospectiveresponsibility,tobediscussedshortly),and thatitisconcernedwithmoralevaluationsofthosehappenings(unlike causalresponsibility,whichisanon-moralconcept).Ifanentityhas moralretrospectiveresponsibility,thenitisanappropriatetargetof reactiveattitudessuchasindignation,resentment,orgratitude.Numerous philosophershavedevelopedtheoriesofgroups’ blameworthinessorof individuals’ blameworthinessingroupcontexts(Jaspers1948;Feinberg 1968;Held1970;French1984;May1987;May1992;Kutz2000;Gilbert 2002;D.Miller2004;Thompson2006;Tollefsen2006;Pettit2007;Mäkelä 2007;Smith2009;Isaacs2011;Strand2012;GoodinandLepora2013).

Moralretrospectiveresponsibilitymightseemtiedtoduties.Itis temptingtothinkthatblameworthinessanddutyaretwosidesofthe samecoin:thatanentityhasadutytoproducesomeactionoroutcome if andonlyif thatentitywouldbeblameworthyifitdidnotproducethat actionoroutcome(Lawford-Smith2015).Ifso,thenperhapsallandonly thegroupsthatarecandidatesforblameworthinessarecandidatesfor duties;andperhapsgroups ’ dutieshaveimplicationsforindividualsthat exactlyparalleltheimplicationsthatgroups ’ blameworthinesshasfor individuals’ blameworthiness.

Butweshouldn’trushtoassumethatblameworthinessanddutyare twosidesofthesamecoin.Plausibly,theyservedifferentfunctionsinour lives.Chapter3willsuggestthatdutyfunctionsasa fittinginputintoan entity’ s first-personfuture-directeddecision-makingaboutwhattodo. Bycontrast,blameworthinessseemstofunctionasa fittingoutputof second-personalpast-directedjudgementsaboutwhatisappropriate (see,e.g.,Smith2015;Shoemaker2015).Iftheyservesuchdifferent functions,thenitisanopenquestionwhetherblameis fittingifand onlyifthetargetoftheblameiscapableofbearingduties.Forthis reason,wecan ’tsimplyreadourtheoryofgroupdutiesoffourexisting theoriesofgroupblameworthiness,evenifweknowoneofthosetheories tobetrue.

What ’smore,evenifblameworthinessanddutyaretwosidesofthe samecoin,it’spossiblethattheargumentsinfavourofsomegroup-type beingeligible(orineligible)fordutieswilldifferfromtheargumentsin favourofthatgroup-typebeingeligible(orineligible)forblameworthiness. Whatmakesacreatureduty-aptmightbedifferentfromwhatmakesit

blame-apt evenifduty-aptnessandblame-aptnessriseandfalltogether. Soweshouldexploregroups’ dutiesintheirownright.

Andevenifgroups ’ duty-aptnessandblame-aptnesshavethesame grounds,weshouldcertainlyexploregroupdutiesseparatelywhenit comestoimplicationsforindividuals:groupdutiesmaywell ‘distribute’ differentlythangroupblameworthiness.Itseemsprimafacieplausible thatamember’ s ‘share’ ofagroup’sblameworthinessdependsupon theirpersonalcontributiontothegroup’ swrong whileamember’ s ‘share’ ofagroup’sdutymightdepend,forexample,ontheirpowerwithin thegroup.Thiscancomeapartfromcausalcontributiontowrongs.To avoidmakingunwarrantedassumptionsonsuchissues,Iwillstayfocused squarelyonduties.Iwillrefertotheoriesofgroupblameworthinessonly whentheyhavepotentialanaloguesregardingduties.

Otherphilosophershavecomeevenclosertomytarget,sincethey havedevelopedtheoriesofgroupduties.Butthesetheorieshavenotbeen comprehensive.Thatis,theyhavenotdealtwithalltypesofgroup.We havetheoriesaboutthedutiesofcollectivesandwhatcollectives’ duties implyformembers,whichI’llengagewithinlaterchapters(e.g.Hindriks 2009;Copp2007;Copp2012).Mostprominentlyinthiscategory,we havethelargebusinessethicscorpusoncorporatesocialresponsibility whichdealswithonlyonetypeofcollective,namely,thefor-pro fit limited-liabilitycompany,andwhichconcernsitselfwitharguingabout thesubstantivecontentofitsduties(ratherthanthemoregeneral questionofwhichkindsofcompanycanhavethosedutiesandwhat thosedutiesimplyformembers)(mostfamously,Friedman1970).Also undertheheadingofcollectives’ duties,wehavethemuchsmallerdebate onthemoraldutiesofstatesandtheirimplicationsforstatemembers (Erskine2001;Erskine2010;Stilz2011;Beerbohm2012;Pasternak2013; Lawford-Smithforthcoming),aswellasthemoraldutiesofintergovernmentalorganizations(Erskine(ed.)2003).Wealsohavetheoriesofthe dutiesof(whatIcall)combinations,insituationswherethemembersof thecombinationhappento findthemselvesthrownintoamorally significantsituationalongsideoneanother(Wringe2014;Wringe 2016;Schwenkenbecher2014;Björnsson2014;Lawford-Smith2015b). Butnoneofthesetheoriescoversallthreetypesofgroup.³

³Thisisn’tquitetrue,insofarassomephilosophersmightthinkwedon’tneedatheory thatdifferentiatesrandomcollectionsfromhighlyorganizedgroups.(WringeandBjörnsson,

Finally,wehavethewell-establishedliteratureonsharedaction,joint agency,andgroupagency.ThisishighlypertinentfortheTripartite Model:inmyterminology,philosophershavedistinguishedcombinationsfromcoalitions(e.g.Bratman2014;Gilbert1989;Sugden2003; Tuomela2007)andhavedistinguishedcombinationsorcoalitionsfrom collectives(e.g.French1984;Rovane1998;PettitandSchweikard2006; ListandPettit2011).Butthesetheoriesdonotattendtothedistinctive issuesinvolvedinduty.(Onealmost-exceptionisGilbert(1993;2006), whoconnectspluralsubjecthoodtotheobligationsofindividuals,but withoutconstruingthelatteras moral obligations.)

Insum,wedon’tyethaveatheorythatstitchesthesestrandsintoone cohesivewhole:atheorythatprovidesaunifiedmodelforallthreeof combinations,coalitions,andcollectives,wherethatmodelisfocused specificallyontheseentities’ capacitytobearduties.Aswe’llsee,my argumentsfortheTripartiteModelwilldisputeothers’ argumentsfor manyoftheabove-mentionednon-comprehensivetheories.

1.3TheTripartiteDistinction

Therearenumerouswaysofdividingupthelogicalspaceofgroups(e.g. Isaacs2011,24–7;List2014).Differentdivisionswillbeusefulfor differentpurposes.Mypurposeistodiscoverdifferencesingroups’ capacitiestobearduties.So,mydivisionbetweencombinations,coalitions,andcollectivesisguidedbywhenandwhysuchdifferencesarise. Idon’tclaimthatthetripartitedistinctionistheall-things-considered mostimportantorfundamentalwaytocategorizegroups.Butthecomingchapterswillarguethatitisthemostimportantandfundamental distinctionforunderstandinggroups’ duties.

It’snotalwayseasytocategorizereal-worldgroupsunderthethree concepts.Aswithmanyconcepts,therearelikelytobevagueorborderlinecases.Notleast,thisisbecausemanygroupsstartoffascombinations,thenslowlybecomecoalitions,thenslowlybecomecollectives. Consider,forexample,protestmovements.It’softenimpossibleto pinpointasinglemomentatwhichsuchanevolvinggroupbecomesa

forexample,mightfallintothiscamp.)Sothesephilosophersmighttaketheirtheoriesof combinations’ dutiestobecomprehensiveacrossallgroups.Thisbookisdevotedtoarguing thatsuchequaltreatmentofdifferentgroup-typeswouldbeamistake.

coalition,andthenbecomesacollective,andthenperhapsfallsbackinto beingacombinationasitachievesitsgoals.Still,thethreetypesarenot justthreesalientpointsonacontinuum.Thiscanbeseenfromthefact thatthereisnoonemetricwithwhichwecouldlabelanysuchcontinuum.Thethreegroupsaredifferentinkind notmerelyindegree eventhoughthereareexamplesonthecuspofeachkind.

I’llstartwiththemostcomplextypeofgroup:collectives.Thisis becausetheothertwogroup-typescanbedefinedlargelyviathefact thattheyarenotcollectives.AlthoughItakecollectives firsthere,the book’ssubstantiveargumentswillbeclearestifthechaptersworkbackwardsthroughthesetypesofgroup startingwithcombinationsand coalitionsinChapters2to5,anddealingwithcollectivesonlyin Chapters6and7.

1.3.1Collectives

Acollectiveisconstitutedbyagentsthatareunitedunderarationally operatedgroup-leveldecision-makingprocedurethatcanattendto moralconsiderations.Somecollectivesare(arguably)alsopartlyconstitutedbymaterialinfrastructure.Buteachcollectiveisatleastpartly andsomearewholly constitutedbyagents.Theagentsareunitedbya decision-makingprocedure.Theprocedureoftenincludesmanysubprocedures,includingtheinformal,tacit,andvagueproceduresthatwe mightsubsumeunderthenotionofacollective’ s ‘culture ’.Inthemost generalterms,a ‘decision-makingprocedure’ takesinbeliefsandpreferences,andprocessesthemtoproducedecisions.Rationaloperation requiresthatcurrentdecisionsfollowfromcurrentbeliefsandpreferences,andthatcurrentbeliefsandpreferencesaccordwithpastbeliefs, preferences,anddecisionsplusanynewevidencethathasarisensince thosepastbeliefs,preferences,anddecisionswerearrivedat.Inany decision-makingentity whetherindividualorcollective thereisthe possibilityofconflictbetween(i)theentity’spastbeliefsandpreferences, (ii)theentity’spresentbeliefsandpreferences,and(iii)newevidence andinputs.Iftheprocedureistoberational,itmustadjudicatethese conflicts decidingwhichbeliefsandpreferenceswillstay,whichwillgo, andwhichwillbedeemedoverriddeninthisinstance.Attheriskof stretchinglanguage,I’llassumethattheseadjudicationsarealso ‘decisions’ thattheproceduremakes,sothattheprocedurecan ‘decide’ on

newbeliefsandpreferences,thatthenfunctionasinputsintonew decisions.

‘Rational’ operationdoesnotrequireperfectrationality.Thisisclear inthecaseofindividuals:Icountasrational,yetit’sfarfromtruethatall mybeliefs,preferences,anddecisionsarefullycoherent.ButIaimto makemybeliefs,preferences,anddecisionsconsistentatonetime,as wellasconsistentacrosstimesandcircumstances.Imostlysucceed.This levelofcoherenceis,likewise,allthat’srequiredforacollectivetocount asrational.

What ’smore,Icanattendtomoralconsiderations.Ioftendoso imperfectly,andIsometimesfailtodosoatall.ButIhaveacognitive structureandmaterialresources(e.g.abody,throughwhichIcanaffect others)thatenablemetoconsiderandactuponmoralconsiderations. Likewise,collectiveshavethebasicstructuralandmaterialresourcesto considerandactuponmoralconsiderations.ThisiswhatImeanby ‘ can attendtomoralconsiderations’.Chapter6willexplainthatthisisnota highbartomeet,thatthegroupsthatmeetit(i.e.collectives)aremoral agents,andthattheycanthereforebearduties.Theupshotisthatalmost allgroupswithdecision-makingprocedurescanbearduties:insufficient rationality,orincapacitytoattendtomoralconsiderations,arerarein groupswithdecision-makingprocedures.

Collectivesmeetthreeindividuallynecessaryandjointlysuf ficient conditionsforthedecision-makingproceduretobe group-level andfor theagentstobe unitedunder thatprocedure.Whenthesethreeconditionsaremet,theagentswhoareunitedundertheprocedurearethe collective’ s members.SoI’llrefertotheseagentsasthe ‘members’ in explainingthethreeconditions.

First,eachmemberiscommitted(evenifonlytacitly)toabidebythe procedure’sresults.Thiscommitmentcanbeoverridden,butispresumptivelydecisiveinthemember’sdecision-making.TousetheUK asanexample:citizens’ behaviourlargelyreflectsacommitmenttoabide bytheUK’sdecisions(thatis,itslaws).Ofcourse,citizenssometimes breaklawsforreasonsofpersonalconvictionorindividualgain.Butas longasoccasionallaw-breakingistheoverridingofageneralpresumptionofabidanceonamember’spart,theyarecommitted.Now,wemight thinktheircommitmentismadeunderduress,andthereforethattheir membership(insofarasithingesonthatcommitment)shouldnot generateanydutiesforthem.Butmembershipdutiesmaywelldemand

lessofmembers,themorecoercedtheirmembershipis.⁴ Chapter7will havemoretosayaboutthis.

Second,thebeliefsandpreferencesthattheproceduretakesasinputs, andthewaytheprocedureprocessesthoseinputstoformdecisions, systematicallyderivefromthebehaviour(e.g.deference,votes,meeting contributions,etc)ofmembers,whilebeing operationallydistinct from theinputsandprocessesthatanymemberuseswhendecidingfor herself.Theseaspectsareoperationallydistinctinsofaras: first,the collectivehasthecapacitytotakeindifferentconsiderationswhen formingitsdecisionsthanthememberstakeinwhenformingtheir owndecisions;second,itsmethodforprocessingthoseconsiderations isdifferentfromthemethodofanyonememberwhendecidingfor herself;andthird,thedecisionsitproducesarenotthestraightforward conjunctionofmembers’ decisions.(ListandPettit(2011)alsoemphasizethis.Chapter6differentiatesmyaccountfromtheirs.)

ToagainusetheUKasanexample:thebeliefs,preferences,and decisionsoftheUKsystematicallyderivefromthemanifestosofpolitical parties,thedirectivesofministers,thejudgementsofjuries,andsoon. The firsttwoofthese(atleast)systematicallyderivefromthevotes, letters,petitions,andsoonofmembers(whichincludesbothcitizens andresidents).SotheUK’sdecisionssystematicallyderivefromthoseof members.

Atthesametime,theUK’sbeliefs,desires,anddecisionsareoperationallydistinct:theUKtakesindifferentinputsthananygivencitizen doeswhendecidingforherself(inparticular,becausetheUKaimsto takeintheinputsof all voters);theUK’smethodsforprocessingits beliefsandpreferencestoformdecisionsincludeparliamentarydebates, Cabinetmeetings,andsoon thesearedecidedly not theprocedures thatmembersusewhenprocessingtheirownbeliefsandpreferencesto maketheirpersonaldecisions;and, finally,thedecisionsoftheUKare notjust ‘thePrimeMinisterdecidesthisandtheForeignSecretary decidesthatand ... ’ Instead,theUKresolvesdifferencesinmembers’ decisionstoarriveatanunequivocalcollectiveposition.(Thisismost clearlyexemplifiedinthe ‘collectiveresponsibility’ ofCabinet(Brady 1999).)

⁴ Gilbert(2006)likewiseallowsforcoercedmembershipduties,though(asnotedabove) shedoesn’tviewtheseasmoralduties.

Thethirdjointly-sufficientconditiononadecision-makingprocedure’ s being group-level,andofagentsbeing unitedunder theprocedure, isthattheenactmentofthegroup ’sdecisionsrequiresactionsonthe partofthemembers,wherethoseactionsarealsoproperlyunderstood asattributabletothecollective.(French(1984)alsoemphasizesthis. Chapter6differentiatesmyaccountfromhis.)SupposetheUKdecides thatitwillteachitsschoolchildrenaparticularcurriculum.Theenactmentofthisdecisionrequiresactionsonthepartofthousandsof members:teachers,regulators,curriculumdesigners,andsoon.The actionsofagiventeacher,whenteachingthiscurriculum,aretheirown. Buttheyarealsoproperlyunderstoodasattributabletothestate.Tosee this,wecanimaginethatthestatetakesthepositionthatevolutionary theorywillbetaughtinbiologyclasses.Toateacherwhodoesn ’tbelieve evolutionarytheory,theiractionofteachingevolutionarytheoryistheir own butitisnotproperlyattributabletojustthem.Instead,theyare doingwhatthestatedemands;theyareactingasaconstituent,organ, part,or(asIwillusuallysay)memberofthestate.Withoutreferringto thestate,wecannotlocatethedecision-makerthatis(inlargepart) behindtheiraction.

I’llsaymoreaboutmyviewofcollectivesinChapter6.Buttheearly chapterswillbemoreintelligibleifIillustratemyview’spermissiveness now.Thiswillhelpdemonstratewhichgroupsdon’tcountascollectives and,so,whichgroupsarethetargetsofChapters2to5.

Toillustratethepermissiveness,imagineagroupofthreefriends whoareatthebeach.Numerousdecisionsmustbemade:wheretolay theirtowels,wheretogoforlunch,andsoon.Suchagroupisprobably composedofagentsthatareunitedunderarationallyoperatedgroupleveldecision-makingprocedurethatcanattendtomoralconsiderations.Theprocedureisprobably conversation-basedconsensus .This procedurecanbecomeestablishedsimplybyeachmember ’stakinga conversationalandconsensualstancetothevariousdecisions each askingtheotherswhere,forexample,theywouldprefertogoforlunch, andwhy,untilallagree.Suchaprocedurecanberationallyoperated, justsolongasthegroupdoesn’tdecide,forexample,bothtoget burgersforlunchandnottogetburgersforlunch.Bytakingpartinthe conversations(whichcanbedonesimplybystayingsilenttoindicate indifference),eachmembertacitlycommitstoabidebytheprocedure’ s results.

Thegrouphasthecapacitytohavedifferentbeliefsandpreferences fromthemembers.Forexample,Lauramightprefersushiforlunch,but uponlearningthepreferencesoftheothers,partakesintheconsensus overburgers.Wecanevenimagineascenariowhereallmembersaimto pleasealltheothers,butallarewrongaboutwhatalltheotherswant,so theyendupusingconversation-basedconsensustogosomewherethat none ofthemwantstogoto.(ThisisperhapsmorelikelyinEnglandthan elsewhere.)Here,thegrouppreferssomething(havingpizza,say)that noneofthemembersprefers.Likewise,suchagroupmightbelieve somethingnomemberbelieves(asGilbert(1987,191)discusses).Such beliefsandpreferencesfunctionasinputsintothegroup’sdecision say, itsdecisiontohavepizza eventhoughthosebeliefsaredifferentinputs fromthoseofanymemberwhendecidingforherself.

Likewise,thegroup processes itsbeliefsandpreferencesdifferently thanthemembersprocesstheirownbeliefsandpreferences:thegroup’ s methodformakingdecisionsis conversation-basedconsensus .Members donotuseconversation-basedconsensustoformtheirownbeliefs, preferences,anddecisions.Sothecollectiveprocessesitsinputsina waynoneoftheindividualsdoes.Andthegroup’sdecisionisdifferent fromtheconjunctionofmembers’ decisions.Evenifallthemembers genuinelywantpizza,itisonlythegroupthatdecides ‘thegroupwill havepizza’.Eachmembermerelydecides ‘Iwillendorsethegroup ’ s havingpizza’.Sothegroup ’sdecisionsarenottheconjunctionofmembers’ decisions.

Finally,theenactmentofthepizza-for-lunchdecisionrequiresthat membersact(bywalkingtothepizzaplace).Theseactionsareattributabletothegroupinthefollowingsense:theexplanationofwhyanyone oftheindividualswalkstothepizzaplacerequiresreferringtothefact thatshe’samemberofagroupthathasdecidedtohavepizzaforlunch. Thegrouphasgivenher(andalltheothers)therole ‘memberwhowalks tothepizzaplace’.Shewalksthereaspartofherroleinthegroup, becauseofherroleinthegroup,becausethatrolehasbeendistributedto herbythegroup.Shegoestothepizzaplaceforlunch,butthisaction alsopartlyconstitutesthegroup’sactionofgoingthereforlunch.

Thispermissivepicturecanbescaleduptolarger-scaleandmore significantcollectives.Thus,onmyaccount,acollectivemightbeagroup whosemembersarestatesworkingtogetheronamilitaryinvasion(in Collins(2014),Iarguedthat ‘coalitionsofthewilling’ canbecollectives),