Contributors

Kathie Aduddell, EdD, MSN, RN

Director/Professor of Nursing

Texas Lutheran University Seguin, Texas

Barbara J. Blake, PhD, ACRN, FAAN

Professor of Nursing

Kennesaw State University Kennesaw, Georgia

Mary Ann Camann, PhD, RN

Associate Professor of Nursing (In Memoriam)

Kennesaw State University Kennesaw, Georgia

Mary de Chesnay, PhD, RN, FAAN Professor of Nursing

Kennesaw State University Kennesaw, Georgia

Bowman O. Davis Jr., PhD

Professor Emeritus of Biology

Kennesaw State University

Kennesaw, Georgia

Ibrahim Elsawy, PhD

Regional Director of Arab World Projects Institute for Global Initiatives Associate Professor Kennesaw State University Kennesaw, Georgia

Marvin A. Friedman, PhD, DABT, DATS, SNF Scientific Advisor Oviedo, Florida

T. Mark Haney, MBA, MHA, FACHE

Senior Vice President, WellStar Hospital System, President of WellStar Paulding Hospital Marietta, Georgia

Govind Hariharan, PHD Professor of Economics, Finance, and Quantitative Analysis

Kennesaw State University Kennesaw, Georgia

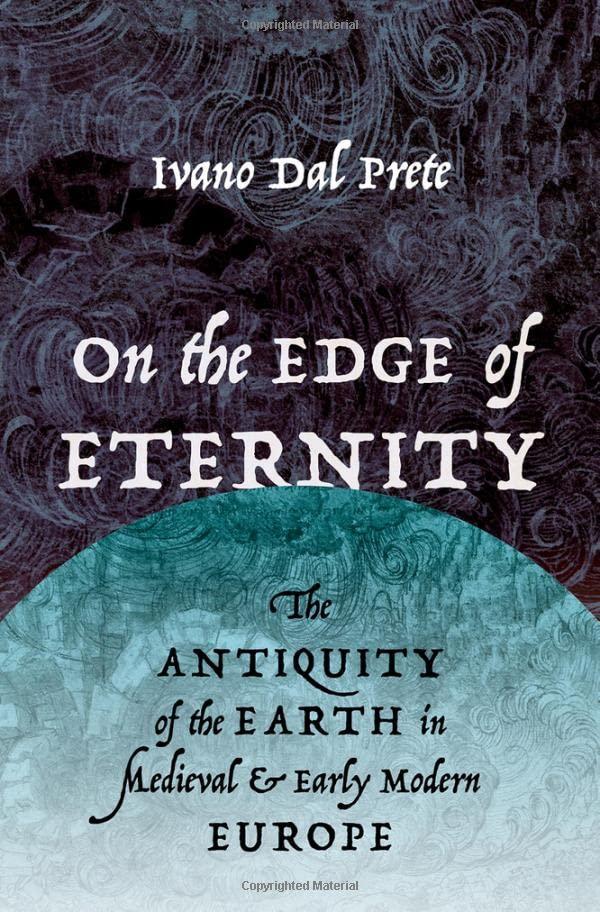

Carol Holtz, PhD, RN

Professor of Nursing

Kennesaw State University Kennesaw, Georgia

Ping Hu Johnson, MD, PHD

Associate Professor of Health, Physical Education, and Sport Science

Kennesaw State University

Kennesaw, Georgia

Michal Lipschuetz, RN, MPH, MSc

Nursing Administration

Hadassah Medical Center Jerusalem, Israel

Janice Long, PhD, RN Professor of Nursing (retired)

Kennesaw State University Kennesaw, Georgia

David B. Mitchell, PhD

Associate Dean, College of Health and Human Services

Distinguished Scholar in Gerontology and Professor of Health, Physical Education, and Sport Science

Kennesaw State University

Kennesaw, Georgia

Monica Nandan, PhD

Acting Dean, College of Health and Human Services

Kennesaw State University Kennesaw, Georgia

Dula F. Pacquiao, EdD, RN, CTN-A, TNS

Consultant

Transcultural Nursing Education, Research and Practice

Adjunct Lecturer, University of Hawai’i

Hilo School of Nursing and Rutgers University School of Nursing

Emily Peoples

Kenneth D. Phillips, PhD, RN Professor and Associate Dean for Research and Evaluation

College of Nursing University of Tennessee Knoxville, Tennessee

Larry Purnell, PhD, RN, FAAN

Professor Emeritus, University of Delaware; Adjunct Professor, Florida International University

Consulting Faculty, Excelsior College, Professor, Universita de Moderna, Italy, Newark, Delaware

Richard L. Sowell, PhD, RN, FAAN Professor of Nursing

Kennesaw State University

Kennesaw, Georgia

Gloria A. Taylor, DNS, RN Professor of Nursing

Kennesaw State University

Kennesaw, Georgia

Orly Toren, PhD, RN

Associate Director for Development Research in Nursing

Hadassah Medical Center Jerusalem, Israel

Astrid H. Wilson, DNS, RN Professor of Nursing Kennesaw State University Kennesaw, Georgia

Anelise Zamarripa-Zoucha, BSN, RN Pittsburg, Pennsylvania

Rick D. Zoucha, PhD, APRN-BC, CT, FAAN

Associate Professor of Nursing Duquesne University Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

Global Health: An Introduction

Carol Holtz

Objectives

After completing this chapter, the reader will be able to:

1. Define global health.

2. Identify global health terminology, agencies, and significant historical events.

3. Relate the state of the world’s population growth and relevance to world health.

4. Discuss the Millennium Developmental Goals and the latest progress made toward their attainment.

5. Relate reasons for health and healthcare disparities worldwide.

6. Define indices of health.

7. Compare and contrast the universal “right to health care” and realistic global healthcare access.

8. Relate global health and healthcare priorities.

9. Discuss the issues related to global migration of healthcare workers.

WHAT IS GLOBAL HEALTH?

Global health is an area of study, research, and practice that places a priority on improving health and achieving equity in health for all people worldwide. It is determined by problems, issues, and concerns that transcend national boundaries. These problems, issues, and concerns emphasize transnational health issues, determinants, and solutions, and involve many disciplines within and beyond the health sciences and promote interdisciplinary collaboration (Beaglehole & Bonita, 2010; De Cock, Simone, Davison, & Slutsker, 2013; Koplan et al., 2009; Macfarlane, Jacobs, & Kaaya, 2008).

Globalization

Globalization is the increased interconnectedness and interdependence of people and countries (WHO, 2014a). In the 1960s, the World Bank first advocated global thinking in regard to health issues with the phrase, “Think globally and act locally” (Beaglehole & Yach, 2003). There are negative aspects to globalization, which include global warming, cross-border pollution, financial crises, international crime, and the spread of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/ acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) and the Ebola virus.

The globalization of disease began with the European explorers and conquerors who came to the Americas and spread smallpox, measles, and yellow fever among the various indigenous populations. They also brought typhus, influenza, and the plague. The poorest were the most vulnerable, whereas the small group of elite, wealthy groups had better nutrition, better health care, and better sanitary (hygienic) conditions. More recently, the spread of HIV/ AIDS, tuberculosis (TB), severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), West Nile virus, Ebola virus, and other infectious diseases have emerged as a global concern. The rapid movement of people and food products as a result of travel has also resulted in new health problems such as mad cow disease (bovine spongiform encephalopathy or BSE) and avian influenza. Globalization has recently changed the lifestyles of developing countries resulting in new chronic diseases from the importation of high-sodium, high-fat fast foods, along with the more sedentary lifestyles promoted by technologies (e.g., TV, appliances). Moreover, in developing countries today, populations are rapidly acquiring chronic diseases (such as heart disease, cancer, stroke, and obesity leading to diabetes), which are adding a double burden of disease given the still challenging acute infectious diseases (Beaglehole & Yach, 2003).

HISTORY OF GLOBAL HEALTH

World Health Organization

The World Health Organization (WHO) was established just after World War II as an intergovernmental agency for the purpose of leading and coordinating worldwide health activities. Its activities are initiated when consensus regarding world health priorities is reached. Today’s world health is elevated when the economic development of nations is improved via the cooperation of governmental and nongovernmental agencies. In the last decade, numerous efforts directed at global health have been initiated, including the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunizations, the Global Tuberculosis Partnership, and the Global Fund on HIV/AIDS (Ruger, 2005).

The World Bank began operations in 1946. Although it was originally established to finance European reconstruction after World War II, today it serves as a major resource for the health, nutrition, and population (HNP) of developing countries. A few examples of the historical activities of the World Bank include the 1968 appointment of Robert McNamara as president of the organization. His term as president resulted in the initiation of a population control program, which provided funding for family planning. In 1971, McNamara emphasized the need to

combat malnutrition. Additionally, in 1974, the Onchocerciasis Control Program was developed in cooperation with the United Nations Development Program, the Food and Agriculture Organization, and WHO. This program was created to eliminate river blindness in West Africa. After 30 years, the onchocerciasis program has protected an estimated 34 million people and also has cleared an estimated 25 million hectares of land for agricultural use (Ruger, 2005).

In 1985, WHO gave $3 million in grants for the World Food Program for emergency food supplies to Sub-Saharan Africa. This effort was followed in 1987 by WHO and the United Nations cosponsoring a Safe Motherhood Project in the same region—the first of a series of global initiatives for this area. In addition, in 1998, WHO lent $300 million to India’s Women and Child Development Program (Ruger, 2005).

At present, the World Bank is the largest financial contributor to health projects throughout the world. When making loans, it allows repayment periods up to 35 to 40 years and gives a 10-year grace period. Although one of the main purposes of the World Bank is to generate and disseminate knowledge, its main advantage over other global healthcare agencies is its ability to generate and mobilize healthcare resources. One of the criticisms of the World Bank is its reliance on user fees, which are said to cause a disproportionate burden on the poor and sick people of the world. For the poorest developing countries the bank’s assistance plans are based on poverty reduction strategies. The World Bank develops a strategy pertaining uniquely to the country in question. The government then identifies the country’s priorities and targets for the reduction of poverty, and the World Bank aligns its aid efforts correspondingly (The World Bank, 2014).

Alma-Ata

In 1978, in Alma-Ata, Kazakhstan (formerly part of the Soviet Union), leaders within the world community assembled to discuss and solve the issue of primary care for all world inhabitants. The Alma-Ata Declaration stated that governments have the responsibility for the health of their people, which can be fulfilled only by the provision of adequate health and social measures. According to this document, a main social target of governments, international organizations, and the whole world community in coming decades was to be the attainment by all peoples of the world, by the year 2000, of a level of health care that would permit them to lead a socially and economically productive life. Primary health care is the key to attaining this target as part of the development of social justice (Hixon & Maskarinec, 2008). The Alma-Ata Declaration states that citizens cannot always provide primary health care by themselves, so governments must include everyone, not just those who can afford health care, in their health-related programs. This document urges member states:

1. To ensure political commitment at all levels to the values and principles of the Declaration of Alma-Ata, keep the issue of strengthening health systems based on the primary healthcare approach high on the international political agenda, and take advantage, as appropriate, of healthrelated partnerships and initiatives relating to this issue, particularly to support achievement of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs).

2. To accelerate action toward universal access to primary health care by developing comprehensive health services and by developing national equitable and sustainable financing mechanisms, mindful of the need to ensure social protection and protect health budgets in the context of the current international financial crisis.

3. To put people at the center of health care by adopting, as appropriate, delivery models focused on the local and district levels that provide comprehensive primary healthcare services, including health promotion, disease prevention, curative care and end-of-life services that are integrated and coordinated according to need.1

In 2005, WHO established a commission on Social Determinants of Health: A Renewal of the Alma-Ata Declaration. In 2008, this commission completed its report recommending a renewal of the goal of primary health care for all and new attention to the need for addressing health disparities worldwide. The Renewal of the Alma-Ata Declaration addressed the following issues:

1. The aging of the world population

2. The plight of indigenous populations

3. Food and nutrition

4. The impact of conflicts and violence

5. The environment and health

6. Global and national inequalities

7. The impact of health on the global economy, social standing, and hierarchy

8. Health disparities among and within nations

9. Best practices and country studies

10. The importance of expanding social determinants of health studies (Hixon & Maskarinec, 2008)

The principles of the Alma-Ata Declaration and Primary Health Care remain at the heart of the global discussions on the post-2015 agenda. These focus on several concepts and priorities, such as sustainable well-being for all, maximizing healthy lives, and accelerating progress on the health MDG’s agenda, particularly on the unfinished business оf the burden of major National Coverage Determinations and universal health coverage (Thirty-fifth Anniversary of the Alma-Ata Primary Health Care Declaration Conference).

Access to Health Care

A continuing goal is access to health care to achieve health equity and increase the quality of life for all people worldwide. Access to healthcare impacts:

1. Overall physical, mental, and social health status

2. Prevention of disease and disability

3. Detection and treatment of health issues

4. Quality of life

5. Preventable death

6. Life expectancy (Access to Health Services: Healthy People, 2014)

1Reprinted from Landscape Analysis of Barriers to Developing or Adapting Technologies for Global Health Purposes, World Health Organization, p. 40. Copyright 2010. http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/documents/ s17778en/s17778en.pdf

STATE OF THE WORLD’S POPULATION

Worldwide, a child born in 1955 had an average life expectancy at birth of only 48 years. By 2000, the average life expectancy at birth had increased to 66 years and, if past trends continue, the global life expectancy at birth is projected to rise to 73 years by 2025. These improvements in longevity have resulted from improved living conditions overall, advances in medical science, and a number of population-level interventions. However, major disparities persist. During the past decade, in low-income countries, average life expectancy at birth increased from 55 to 57 years (3.6%), while increasing from 78 to 80 years (2.6%) in high-income countries. The world’s population as of October 31, 2011, reached 7 billion. Although women on average are having fewer children than they were in the 1960s, the world population continues to rise. At present, there are more people who are younger and also more people who are older than ever before. In some of the poorest countries, high fertility rates hamper the infrastructure development and perpetuate poverty, while in some of the richest countries, there are great concerns regarding low fertility rates and too few people entering the job market. The unemployed people of many nations who wish to migrate from developing countries to developed countries are finding more national borders closed to them. Gaps between rich and poor are widening in almost every location worldwide (UNFPA, 2011).

In 2050, the world population is projected to total 9.15 billion. It is expected that in developing countries, most families will have two or fewer children per family. The largest increases in population growth rates will occur in Africa. Many countries are facing a shrinking pool of working-age individuals (ages 15–64 years), who are needed to support the older adult population. This imbalance may jeopardize pension guarantees and longterm healthcare programs for the elderly. Within the United States, the largest population growth is expected to come from immigration and from growth of the older adult population (Bremner et al., 2010).

The United Nations Family Planning Association (UNFPA) has validated, across nations, the inadequate resources, gender bias, and gaps in serving the world’s poor (UNFPA, 2011). Many developing countries have initiated population projects to reduce poverty and have developed laws and policies to protect the rights of women and girls. They have introduced reproductive health services as part of primary health care, increased the skills of birth attendants, and provided more prevention and treatment of HIV/AIDS. Many couples today continue to lack access to birth control. Birth complications remain the leading cause of death of women worldwide, with five million new fatalities per year. Every minute, a woman dies in pregnancy or in childbirth and another 20 to 30 women suffer serious injury or disability; most of these women die in developing countries of preventable or treatable complications. A wide disparity in global survival rates among the rich and poor women within countries is evident (UNFPA, 2011).

World Population Statistics and Related Health Issues

Estimates for the year 2050 range from between 3.2 and 24.8 billion people (The World Bank, 2013).

Life Expectancy

According to IndexMundi (2014a; 2014b), statistics indicated the following for the world:

1. World life expectancy—males: 68.09 years and females: 70.24 years.

2. World birth rate—18.9 births per 1,000 population. The total fertility rate (2014) ranges from 7.35 births per woman in Niger, 6.57 in Uganda, to 2.22 in Peru.

3. World death rate—7.9 deaths per 1,000. The world range leads in South Africa with 17.23 deaths per 1,000 and Russia with 16.03 deaths per 1,000, to the United Arab Emirates with 2.04 per 1,000 and Qatar with 1.55 per 1,000.

WHO’s annual statistics report shows that low-income countries have made the greatest progress, with an average increase in life expectancy by 9 years from 1990 to 2012. The top six countries where life expectancy increased the most were Liberia with a 20-year increase (from 42 years in 1990 to 62 years in 2012), followed by Ethiopia (from 45 to 64 years), Maldives (58 to 77 years), Cambodia (54 to 72 years), Timor-Leste (50 to 66 years), and Rwanda (48 to 65 years) (IndexMundi, 2014a; 2014b).

Global Family Planning Needs in Developing Countries

Many emerging economies have experienced very rapid increases in their contraceptive coverage, enabling steady fertility declines. By contrast, the least developed countries, mostly located in Sub-Saharan Africa, are just beginning to use modern contraceptives (Rwanda and Ethiopia are among the few exceptions). An unmet need for family planning remains high in Sub-Saharan Africa. About 25% of couples who would like to postpone their next birth by 2 years do not currently use a contraceptive method. This need could be met by improving knowledge of contraception and increasing the supply of reproductive health services so that couples can better plan their families (Guengant & May, 2013).

Global Health Research

The World Health Organization (2013), in its population data sheet, calls for the following improvements:

1. Increased international and national investment and support for research addressing improved healthcare coverage for all countries.

2. Closer collaboration between researchers and policymakers.

3. Building research capacity by developing a local workforce of well-trained researchers.

4. All countries having comprehensive codes of good research practice.

5. Global and national research networks to coordinate research and increase collaboration and information exchange.

Gaps Between Rich and Poor Countries

A boy born in 2012 in a high-income country can expect to live to the age of around 76, which is 16 years longer than a boy born in a low-income country (age 60). For girls, the difference is

even wider; a gap of 19 years separates life expectancy in high-income (82 years) and low-income countries (63 years). Wherever they live in the world, women live longer than men. The gap between male and female life expectancy is greater in high-income countries where women live approximately 6 years longer than men. In low-income countries, the difference is around three years. Women in Japan have the longest life expectancy in the world at 87 years, followed by Spain, Switzerland, and Singapore. Female life expectancy in all the top 10 countries was 84 years or longer. Life expectancy among men is 80 years or more in nine countries, especially as the declining use of tobacco helps people live longer in several countries. At the other end of the scale, life expectancy for both men and women is still less than 55 years in nine Sub-Saharan African countries: Angola, Central African Republic, Chad, Côte d’Ivoire, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Lesotho, Mozambique, Nigeria, and Sierra Leone (CDC, 2014).

WORLD HEALTH STATISTICS

The following facts, from WHO’s World Health Statistics report, characterize the current state of world health (WHO, 2014c):

• The top three causes of years of life lost due to premature death are coronary heart disease, lower respiratory infections (such as pneumonia), and stroke.

• Worldwide, a major shift is occurring in the causes and ages of death. In 22 countries (all in Africa), 70% or more of years of life lost (due to premature deaths) are still caused by infectious diseases and related conditions. Meanwhile, in 47 countries (mostly high income), noncommunicable diseases and injuries cause more than 90% of years of life lost. More than 100 countries are transitioning rapidly toward a greater proportion of deaths from noncommunicable diseases and injuries.

• Around 44 million (6.7%) of the world’s children, aged less than 5 years, were overweight or obese in 2012. Ten million of these children were in the WHO African Region where levels of child obesity have increased rapidly.

• Most deaths among those under five occur among children born prematurely (17.3%); pneumonia is responsible for the second-highest number of deaths (15.2%).

• Between 1995 and 2012, 56 million people were successfully treated for tuberculosis and 22 million lives were saved. In 2012, an estimated 450,000 people worldwide developed multidrug-resistant tuberculosis.

• Only one-third of all deaths worldwide are recorded in civil registries along with cause-ofdeath information.

THE CDC GLOBAL HEALTH STRATEGY/HEALTH CHALLENGES

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) created major goals, stated in its Health Challenges report as the following (CDC, 2014a):

1. Health impact—prevent new infections

a. Reduce TB

b. Reduce malaria