https://ebookmass.com/product/pediatric-sonography-fifthedition/

Instant digital products (PDF, ePub, MOBI) ready for you

Download now and discover formats that fit your needs...

Pediatric Sonography 4th Edition, (Ebook PDF)

https://ebookmass.com/product/pediatric-sonography-4th-edition-ebookpdf/

ebookmass.com

Rogers’ Textbook of Pediatric Intensive Care Fifth Edition

https://ebookmass.com/product/rogers-textbook-of-pediatric-intensivecare-fifth-edition/

ebookmass.com

Sonography Principles and Instruments 9th Edition – Ebook PDF Version

https://ebookmass.com/product/sonography-principles-andinstruments-9th-edition-ebook-pdf-version/

ebookmass.com

Rosenberg’s Molecular and Genetic Basis of Neurological and Psychiatric Disease 6th Edition Edition Roger N. Rosenberg

https://ebookmass.com/product/rosenbergs-molecular-and-genetic-basisof-neurological-and-psychiatric-disease-6th-edition-edition-roger-nrosenberg/ ebookmass.com

Rethinking Roma: Identities, Politicisation and New Agendas 1st Edition Ian Law

https://ebookmass.com/product/rethinking-roma-identitiespoliticisation-and-new-agendas-1st-edition-ian-law/

ebookmass.com

Neurointerventions, Crime, and Punishment: Ethical Considerations Jesper Ryberg

https://ebookmass.com/product/neurointerventions-crime-and-punishmentethical-considerations-jesper-ryberg/

ebookmass.com

Personal Foul Jerica Macmillan

https://ebookmass.com/product/personal-foul-jerica-macmillan/

ebookmass.com

Pulmonary Physiology, 10th Edition Michael G. Levitzky

https://ebookmass.com/product/pulmonary-physiology-10th-editionmichael-g-levitzky/

ebookmass.com

Kira's Wolf: A Billionaire Shifter Romance (Maid for the Shifter Book 2) Charlene Perry

https://ebookmass.com/product/kiras-wolf-a-billionaire-shifterromance-maid-for-the-shifter-book-2-charlene-perry/

ebookmass.com

Children’s Speech: An Evidence Based Approach to Assessment and Intervention (What’s New in Communication Sciences & Diaorders) 1st Edition, (Ebook PDF)

https://ebookmass.com/product/childrens-speech-an-evidence-basedapproach-to-assessment-and-intervention-whats-new-in-communicationsciences-diaorders-1st-edition-ebook-pdf/

ebookmass.com

Preface

Since the publication of the fourth edition of Pediatric Sonography in 2010, ultrasound equipment and techniques continue to improve and sonographic imaging of the pediatric patient continues to evolve. We have seen innovations in software and technology, such as elastography, contrast agents, and 3D imaging, which have increased ultrasound utilization and our understanding of the role of ultrasound in the evaluation of disease processes in children. The fact that ultrasound is noninvasive and does not use ionizing radiation makes a compelling case for even more widespread use of this modality in the pediatric population. Furthermore, compared with computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging, ultrasound is a faster and more cost-effective imaging test for evaluating many pediatric diseases. Given these facts, there is a need for an updated and informative text that can be used as a tool for learningandtrainingaswell asareferencesource.

The goal of the fiftheditionof Pediatric Sonography is againtoprovide a comprehensive text on the clinical applications of sonography in a pediatric population. As in prior editions, I have asked highly knowledgeable and recognized colleagues in sonography to share their experience and insights in their areas of expertise. Virtually all chapters have been extensively revised with new illustrations and images added to reflect important newconceptsandimagingfindings.

This book is intended primarily for practicing radiologists, radiology residents and fellows, and sonographers. Other physicians, such as pediatricians and surgeons, also can derive useful information about the clinical indications and relative value of sonography in the pediatric patient.

frequently used in daily practice. I have strived to produce a comprehensive text that will be easily readable and offer guidance for radiologists and sonographers on the appropriate use of sonography in imagingpediatricdiseases.

Acknowledgments

Writing a book is a task that requires time and commitment from many people. As editor, it would not have been possible for me to complete this task without the important contributions of manyother individuals,whoI acknowledgebelow.

I offer sincere thanks to Dr. Ellen M. Chung, Department of Radiologic Pathology, Armed Forces Institute of Pathology; Drs. William D. Middleton, Kathryn A. Robinson, James R. Duncan, Sarah E. Connolly, and Eric P. Eutsler of the Mallinckrodt Institute of Radiology; Dr. Oscar M. Navarro of The Hospital for Sick Children; Dr. Prakash Masand of Texas Children’s Hospital; and Dr. Kassa Darge of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. They graciously shared their vast experience and outstanding images to bring depth to their chapters in this edition of Pediatric Sonography.

Mythanks alsogoes tomytalentedsonographers,DeborahReiter,Janet Hurt, Angela Heffernan, Shelly Lopez, and Lindsey Snodgrass at the Mallinckrodt Institute of Radiology. Their skill and dedication to performing high-quality examinations led to the creation of many outstandingimages.

I would also like to express my appreciation to the publishing team at Wolters Kluwer for their assistance and professionalism in the development of Pediatric Sonography, 5th edition. Special thanks to Sharon Zinner, Ashley Fischer, and Lisa Koepenick who guided me through the development of the book. Of course, I need to thank Ryan Shaw who cajoled me into taking up the editorial pen once again. I also express my deepest appreciation to Roxanne Klaas and Bridgett Dougherty, the project managers during the production phase, who transformed the pages into print and prepared the illustrative material.

There could not be a better or more dedicated team with which to work. Without the talents and efforts of this group, this book would not have happened.Thanksfor makingthisbookpossible.

Finally, I wish to thank one more very important person−my husband, Barry A. Siegel, MD, for his support and patience during the many hours that I spent writing and editing this book. His encouragement made the completionof thisbookareality.

Contributors

William D Middleton,KathrynA Robinson,andMarilynJ Siegel

William D Middleton,KathrynA Robinson,andMarilynJ Siegel

Siegel

EllenM ChungandMarilynJ Siegel

MarilynJ SiegelandPrakashM Masand

MarilynJ

Oscar

KassaDargeandMarilynJ.Siegel

MarilynJ

MarilynJ.Siegel

MarilynJ.Siegel

Online Appendix (see eBook)

Please access the eBook bundled with this textto view the online appendix. Access instructions are located on the inside frontcover.

PhysicalPrinciplesand Instrumentation

WILLIAM D.MIDDLETON,KATHRYN A.ROBINSON,AND MARILYN J.SIEGEL

Acoustics

WavelengthandFrequency

PropagationofSound

Instrumentation

Transmitter

Transducer

Receiver

ImageDisplay

ImageStorage

Real-TimeImaging

MechanicalTransducers

Multiple-ElementArray Transducers

TransducerSelection

HarmonicImaging

ExtendedField-of-View Imaging

Real-TimeCompounding

Three-DimensionalUltrasoundImaging

Doppler Sonography

Continuous WaveDoppler

PulsedDoppler

ColorDoppler

PowerDoppler

B Flow

Elastography

Basic Principles ofElastography

Elastography Techniques

ContrastAgents

MicrobubbleImaging

PulseInversionImaging

MechanicalIndex

CHAPTER

Ultrasonography has been a valuable method for displaying normal and abnormal anatomyfor manyyears.Therearemanyreasonswhyit is an especially attractive imaging technique in the pediatric age group. One of the most important features of sonography is its lack of ionizing radiation. One important goal in imaging the pediatric patient is to obtain diagnostic information with the least amount of radiation exposure. Sonography can provide clinically useful information without apparentbiologiceffectsonthepatientortheoperator.

A second appealing aspect of sonography is the real-time nature of the examination. This makes it easier to examine patients who cannot suspend respiration, are uncooperative, or are crying, all common problems among pediatricpatients.Inaddition,thereal-timenatureof theexaminationallows evaluationofrapidlymovingstructures,suchastheheart.

A third advantage of sonography is its multiplanar imaging capability. Newer real-time equipment enables great flexibility in the selection of imaging planes and the ease of altering these planes. This capability is especially helpful in determining the origin of pathologic masses and in analyzing spatial relationships of various structures. These advantages have been expanded even further with the advent of three-dimensional (3D) ultrasound.

Another advantage of sonography in the pediatric age group is its excellent resolution, which is related to the size of the patient and the smaller amounts of body fat. The lack of significant body wall and intraabdominal fat inmost small childrenis a great advantage inthe examination of pediatric patients because fat generally degrades the ultrasonographic image. For a given sonographic unit and type of transducer, higher transmitted frequencies provide better image resolution, but poorer penetration.These conflictingcharacteristics of transducer frequencyforce a compromise in adults in whom lower frequencies must be used to obtain adequate depth of penetration at the expense of image resolution. However, the need for greater depth of penetration is less in children than it is in adults, reflecting the differences in body habitus. Therefore, higher frequency, higher resolution transducers can be used routinely in pediatric examinations.

The ability to perform the examination using portable equipment is another advantage that sonographyhas over other cross-sectional modalities, suchas computedtomography(CT) andmagnetic resonance imaging(MRI).

This is obviously important in evaluating patients who cannot be transported totheradiologydepartment becauseof their underlyingconditionor because oftheirdependenceonmonitoringdevices.

Finally, in the era of medical cost containment, the relative inexpensiveness of ultrasonography, compared with CT or MRI, makes it an attractiveimagingstudyformanyclinical problems.Theissueofcost makes ultrasonography especially appealing in situations in which multiple sequential examinations are necessary or when screening of large patient populationsisdesired.

All of these factors make ultrasonography an extremely valuable tool in the investigation of pediatric disorders. Therefore, any radiologist who performs diagnostic ultrasonography on pediatric patients must have an understanding of the physical principles of this technique and the instrumentation available for detecting and displaying the acoustic information. This information has been described in detail in several comprehensive textbooks, chapters, and review articles (1-6). The following chapter will be limited to the basic physical principles and the instrumentation that are most relevant to the practice of diagnostic ultrasound.

ACOUSTICS

WAVELENGTH AND FREQUENCY

Sound is the result of mechanical energy traveling through matter in the form of a wave with alternating compression and rarefaction of the conducting medium. Human hearing encompasses a range from 20 to 20,000 Hz. Ultrasound differs from audible sound only in its higher frequency. The term ultrasound refers to sound above the audible range (i.e., >20 kHz). Diagnosticsonographygenerallyoperatesatfrequenciesof1to20MHz.

P

ROPAGATION

OF SOUND

Most diagnostic ultrasound examinations use brief bursts of energy that are transmitted into the body where they travel through tissue. In tissue and fluid, sound is propagated along the direction of the particles being displaced. The resistance of the tissues being compressed largely determines the speed at which the sound wave travels. The velocity of propagation is constantforagiventissueandisnotaffectedbythefrequencyorwavelength

of the sound wave. In soft tissues, the assumed average propagation velocity is1540m/s.Fluidandfathaveslightlyslowerpropagationvelocities.

After the sound pulse is generated and transmitted into the body, it can be reflected, refracted, scattered, or absorbed (7). Reflection or backscatter occurswheneverthesoundpulseencountersaninterfacebetweentissuesthat have different acoustic impedances. Acoustic impedance is equal to the tissue density times the speed of sound propagation in that tissue. The amount of soundthat is reflectedat aninterface varies withthe difference in acoustic impedance between the tissues and the angle of incidence of the soundbeam.Thegreater theacousticimpedancemismatchis,thegreater the backscatter or sound reflection. Reflection does not occur in a homogeneous medium that has no interfaces to reflect sound, and consequently, the mediumappearsanechoicorcystic.

Refraction refers to a change in the direction of the sound as it passes from one tissue into another. Refraction occurs when sound encounters an interface between two tissues that transmit sound at different speeds. Because the sound frequency remains constant, the sound wavelength must change to accommodate the difference in the speed of sound in the two tissues. The result of this change in wavelength is a redirection of the sound pulse as it passes through the interface. Refraction is important because it is one of the causes of misregistration of a structure on an ultrasound image. Refraction and its resultant artifacts are discussed in more detail in Chapter 2.

Scattering refers to the redirection of sound in many different directions. This phenomenon occurs when the sound pulse encounters an acoustic interface that is not smooth. Scattering can also occur in solid tissues and organs as a result of the heterogeneity (i.e., multiple small interfaces) of biologicaltissues.

Absorption refers to the loss of sound energy secondary to its conversion to thermal energy. Absorption is greater in soft tissues than in fluid, and it is greater in bone than in soft tissues. Sound absorption is the major cause of acousticshadowing.

The combined effects of reflection, scattering, and absorption are a decrease in the intensity of the sound pulse as it travels through matter. This decrease in intensity is termed attenuation. As a result of attenuation, an acoustic interface in the deeper tissues produces a weaker reflection than an identical interface in the superficial tissues. To compensate for this

degradation in sound intensity, echoes returning from the deeper portions of the image are electronically amplified. This is referred to as distance gain compensation or time gain compensation.

INSTRUMENTATION

The essential components of all scanners are a transmitter to energize the transducer;thetransducer,whichisthesourceofthesoundpulses;areceiver to detect the reflected signals; a display that presents the data for viewing; andastoragemodule.

TRANSMITTER

Thetransmitteractivatesthetransducer,whichcausesit tovibrateandcreate a pulse of sound that can be transmitted into the body. This is done by the application of short high-amplitude voltage pulses. The maximum voltage that may be applied to the transducer and hence, the acoustic output of diagnosticscanners,islimitedbyfederalregulations.

TRANSDUCER

The transducer converts electric energy generated by the transmitter into acoustic pulses, which are transmitted into the patient. It also receives the reflected echoes, converting pressure changes back into electric signals. Becausethecrystal element converts electricenergyintopressurewaves and viceversa,itisreferredtoasa piezoelectric crystal (i.e.,pressureelectric).

Thesoundpulsesusedfordiagnosticsonographyaregeneratedbyceramic crystal elements housed within the ultrasonic transducer. These ceramic crystals deform when the transducer is electrically stimulated, resulting in a band of frequencies. The range of frequencies produced by a given transducer is referred to as the bandwidth. The preferential frequency produced by a transducer is equal to the resonant frequency of the crystal element,which,inturn,isdependentonthethicknessofthecrystal.

The ultrasound pulses produced by the transducer must travel through tissue to generate diagnostic information. The transfer of energy from the transducer to tissue requires the use of a coupling gel. After entering the body, the ultrasound pulses may be propagated, reflected, refracted, scattered, or absorbed as discussed above. The small pressure changes from reflections that return to the transducer distort the crystal element and

stimulate the transducer. This distortion once again generates an electric pulsethatcanthenbeprocessedintoanimage.

RECEIVER

The returning echoes hit the transducer face, producing voltage differences across the piezoelectric crystal. The receiver detects, amplifies, and processes the voltage changes that return to it. The time gain compensation control amplifies the weaker signals from deeper structures, thus compensating for tissue attenuation. The receiver also compresses and remaps the backscattered signals. This changes the brightness of different echolevelsintheimage,whichinturnaffectsimagecontrast.

IMAGE DISPLAY

A- and B-Mode Imaging

Ultrasound images have been displayed in A- and B-mode formats. The A(amplitude) mode format was the earliest one for displaying sound signals returning to the transducer. With this format, the reflections arising from tissue interfaces were displayed in graphic form with time on the horizontal axisandechoamplitudeontheverticalaxis.

The B-(brightness) mode displays the returning sound signal twodimensional (2D) image with higher amplitude echoes appearing brighter than lower amplitude echoes. In both A- and B-mode sonography, the distance of the reflector from the transducer is obtained by converting the timetakenfortheechotoreturntothetransducertoadistance.Thisisbased on the speed of sound in soft tissues, which is equal to 1540 m/s. In general, the range of brightness should be as wide as possible to differentiate small differencesinechointensity.

Intheearly2Dunits,theB-modetransducerwasattachedtoanarticulated arm that wascapableof determiningtheexact locationandorientationof the transducer in space. This allowed the origin of the returning echoes to be localized in two dimensions. Then, by sweeping the transducer across the patient’s body, a series of B-mode lines of information could be added togethertoproducea2Dimage.WithstaticB-modeimaging,it waspossible to view large organs, such as the liver, in one cross-sectional image. The major disadvantage of static B-mode imaging was its lack of real-time

capabilities. Because of this limitation, static articulated-arm B-mode deviceshavenowbeenreplacedbyreal-timeunits.

IMAGE STORAGE

Permanent storage of images for analysis and archiving was originally done in the form of transparencies printed on hard-copy radiographic film. However, computers and digital storage are now used for reviewing images and archiving the sonographic data. Digital imaging and communications in medicine (DICOM) standards are in place to sustain image compatibility between different ultrasound systems and transfer and storage of these images.

REAL-TIMEIMAGING

Real-time imaging permits investigation of anatomy and motion. The effect of motion is achieved when images are displayed at rates of several frames per second. Thus, the information is regarded as being viewed in real time. Severaltransducersareavailableforreal-timeimaging.

MECHANICAL TRANSDUCERS

The earliest and simplest transducer design was the mechanical sector transducer that used a single large piezoelectric element to generate and receive the ultrasound pulses. Beam steering was accomplished by an oscillating or rotating motion of the crystal element itself or by reflection of the sound pulse off an oscillating acoustic mirror. Beam focusing was done byusingdifferent-shapedcrystal elementsorbyattachinganacousticlensto the transducer.The disadvantage of the mechanical sector transducer was the absence of variable focusing. The only way to vary the focus distance was to switch to a completely different transducer. Because of their lack of flexibility, mechanical sector transducers have almost entirely been replaced bymultiple-elementelectronictransducers,commonlycalledarrays.

MULTIPLE-ELEMENT ARRAY TRANSDUCERS

The arraytransducers containgroups of small crystal elements that cansteer and focus the ultrasound beam electronically (Figs. 1-1 and 1-2) (8). The basictypesofarraysarelinearandcurvilinear.

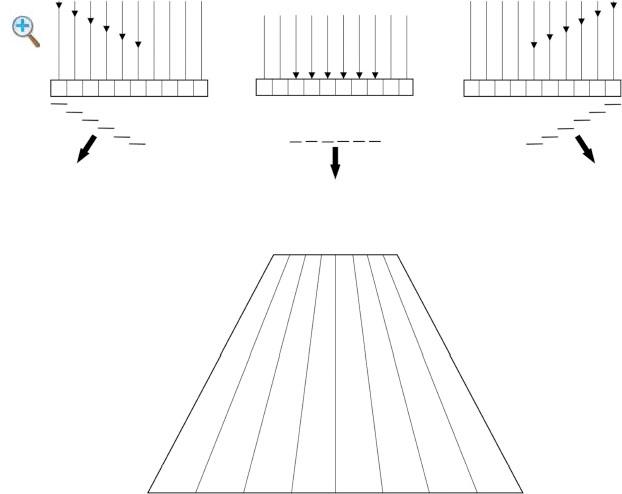

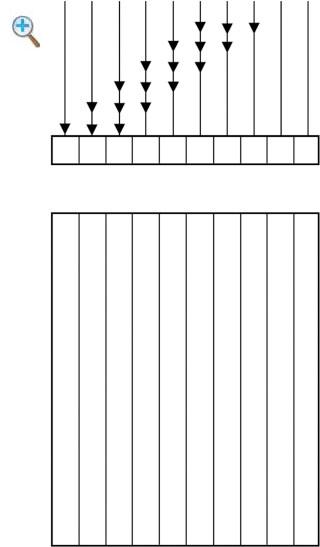

Fig.1-1 Beam steering. By ring the elements on the right side of the array first, a composite pulse is created that is steered to the left By firing all of the elements simultaneously, the composite pulse is steered straight down By firing the left elements first, the pulse is steered to the right. The resulting image has a sector/trapezoidalformat

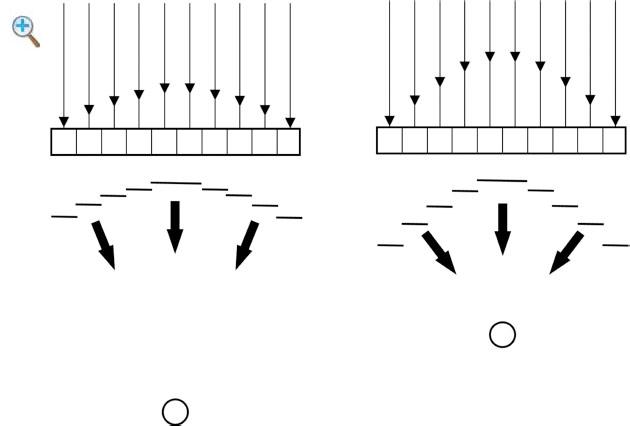

Fig. 1-2 Focusing of array transducers. By slightly delaying the firing of the center elements, the composite pulse is focused in the far field By increasing the delay in firingofthecentralelements,thecompositepulseis focusedinthenearfield.

Linear Array or Linear Sequenced Array Transducers

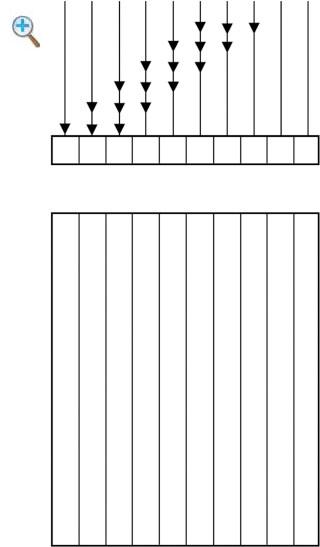

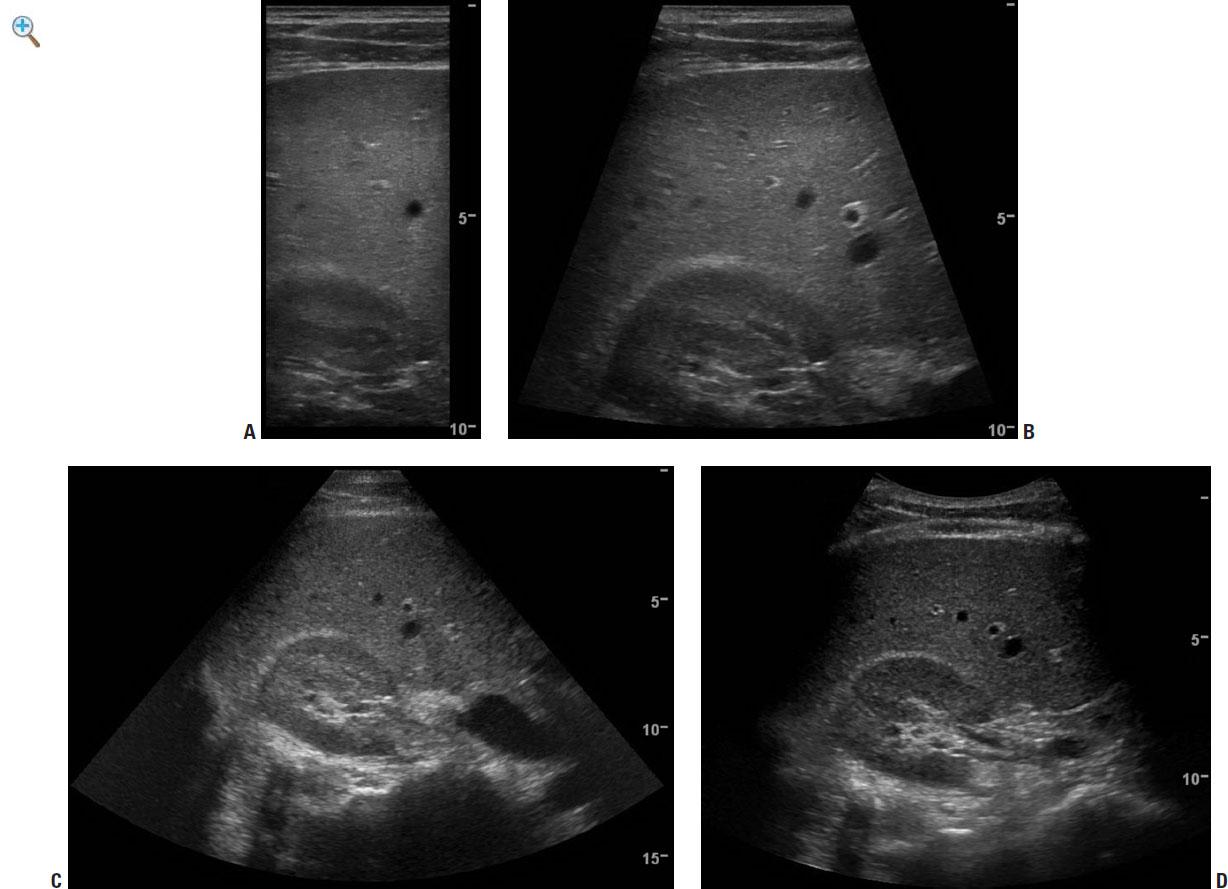

Linear arrays activate a group of adjacent elements to generate each pulse. The individual elements of this transducer are arranged in a linear fashion. By firing groups of transducer elements in succession, a series of sound pulses is produced along the face of the transducer and the beam travels sequentially from one side of the transducer to the other (Fig. 1-3). With earlylinear arrays,eachsoundpulse traveledinthe same direction(parallel) and was oriented perpendicular to the transducer surface, resulting in a rectangular image (Figs. 1-3 and 1-4A). Currently, beam steering is commonly used in linear array transducers so that a trapezoidal format is also available (Fig. 1-4B). The major advantages of linear array transducers are high resolution in the near field and a large superficial field of view. Focusing is more uniform in the center and periphery of the image because there is little or no beam steering. The major disadvantages of linear arrays are their limited deep field of view and their large size, which limits their useinareaswhereaccessislimited,suchasinintercostalscanning.

Fig. 1-3 Linear array transducer. In this illustration, there are 10 individual crystal elements Each composite pulse is created by the activation of three adjacent elements The first pulse is created by activation of elements 1 through 3, the second pulse by elements 2 through 4, the third pulse by elements 3 through 5, and soon Theresultingimageformatis rectangular

The disadvantages of the linear array transducers can be minimized by steeringthesoundpulses sothat theydivergefrom eachother.Thetwotypes of probes that diverge sound pulses are the vector and curved linear arrays. Both transducers produce images with sector display formats and large surface field of views. The vector or trapezoidal array transducers can be thought of as small linear arrays that operate only in the trapezoidal format. They produce a sector-like image format with a flat apex (Fig. 1-4C). The curved linear array transducer (also known as the curved array, convex array,

and curvilinear array) (Fig. 1-4D) produces an image with a convex instead ofaflatapex.

Two-DimensionalArrays

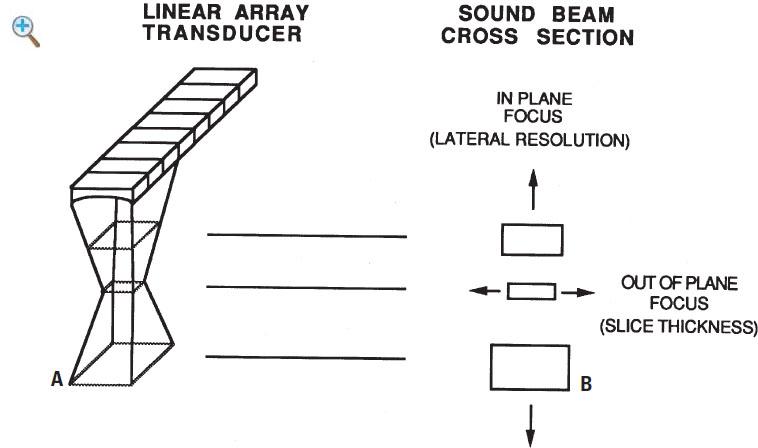

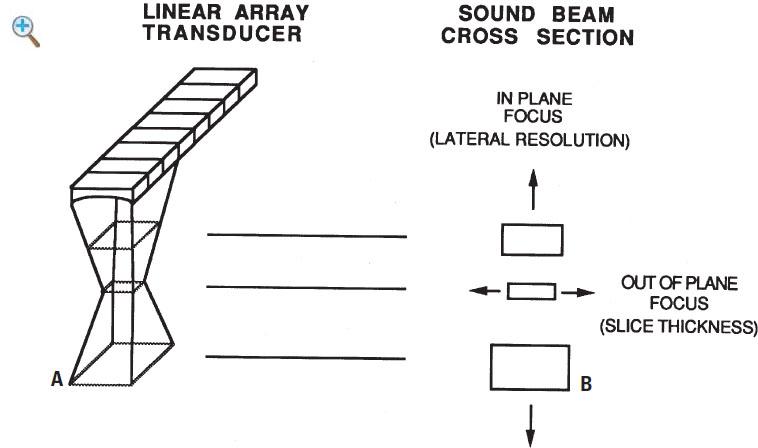

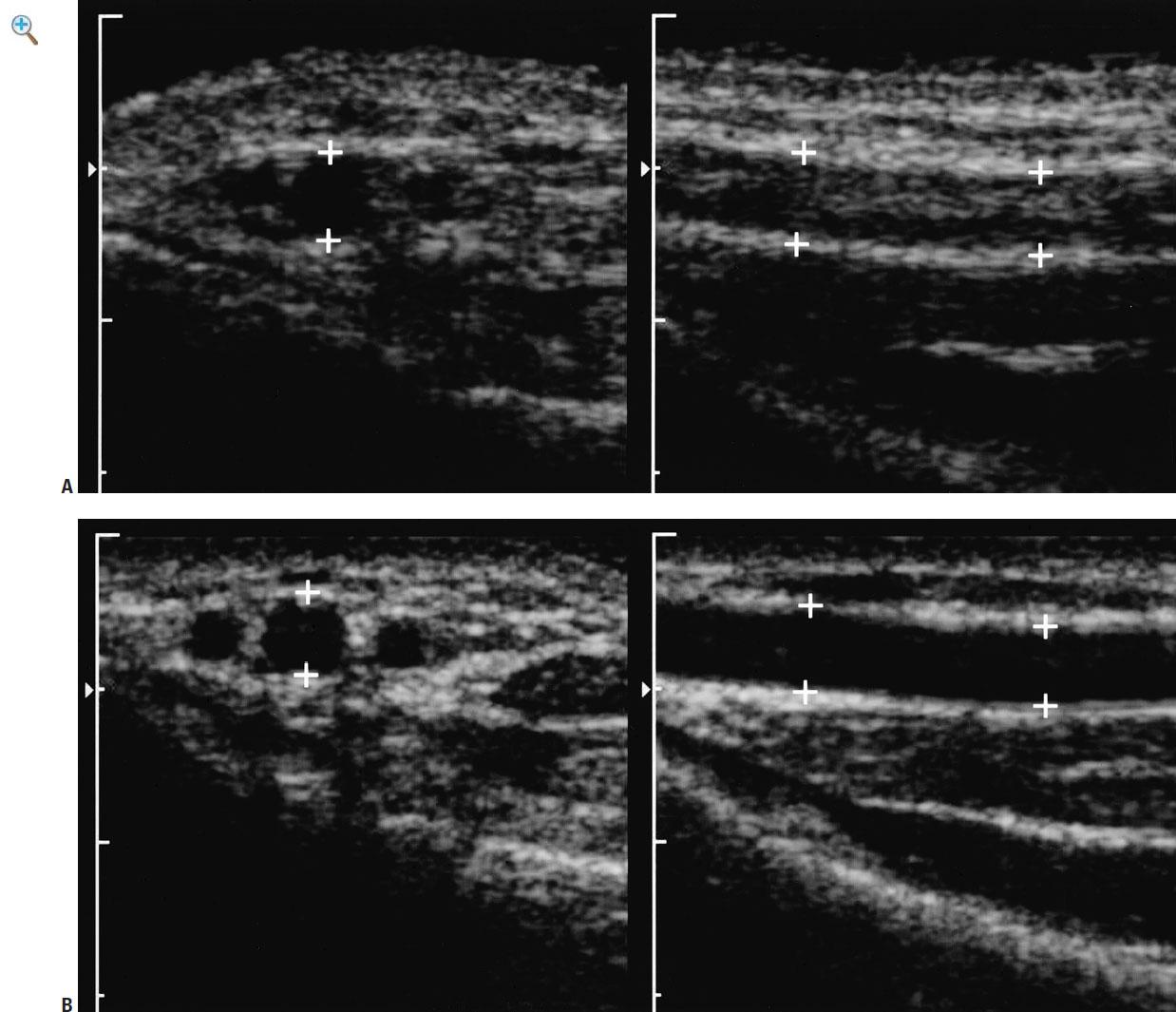

The array transducers described above allow for variable depth and electronically controlled focusing of the sound beam in the plane of the image but not inthe directionperpendicular tothe plane of imaging.The net effect of conventional in-plane focusing is on lateral resolution in the plane of imaging. Focusing the beam in the out-of-plane direction (also called the elevation plane) affects the out-of-plane resolution, which is identical to the slice thickness. With the conventional array transducers, the slice thickness isfixedandcannotbevariedbytheoperator(Fig. 1-5).

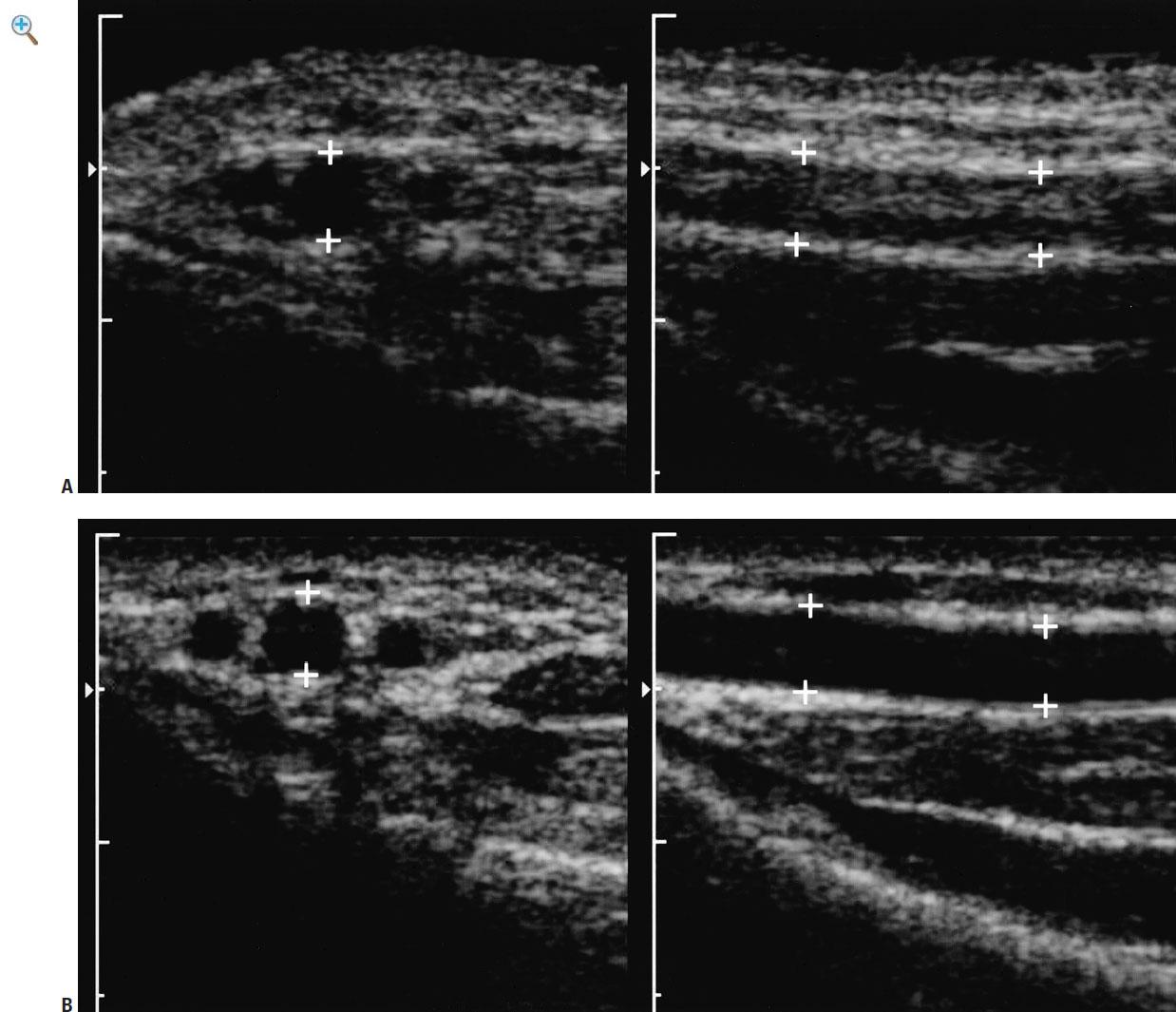

A solution to variable focusing in the elevation plane is the matrix or 2D array (Fig. 1-6). These probes have crystal elements that are stacked in columns as well as rows. They allow for variable slice thickness that is controlled electronically. They also allowfor 3Dimaging, real-time imaging inorthogonalplanes,andothertimeconsumingtechniques.

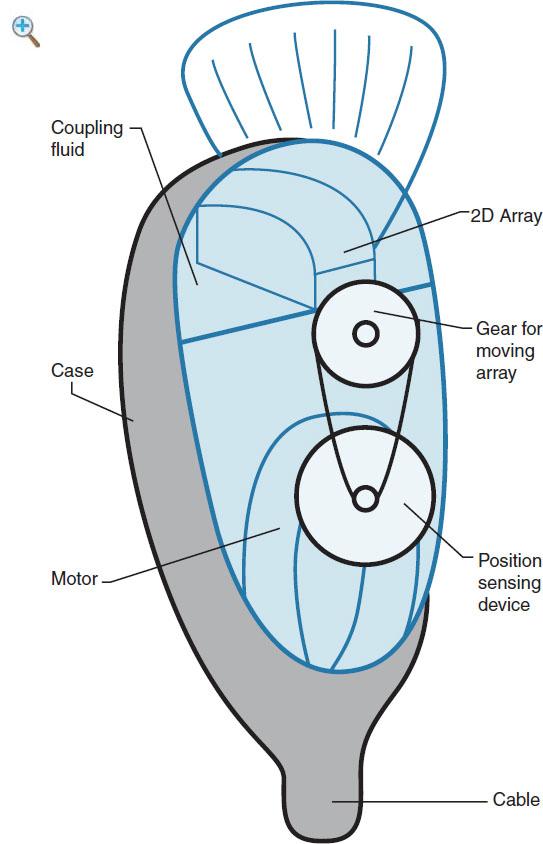

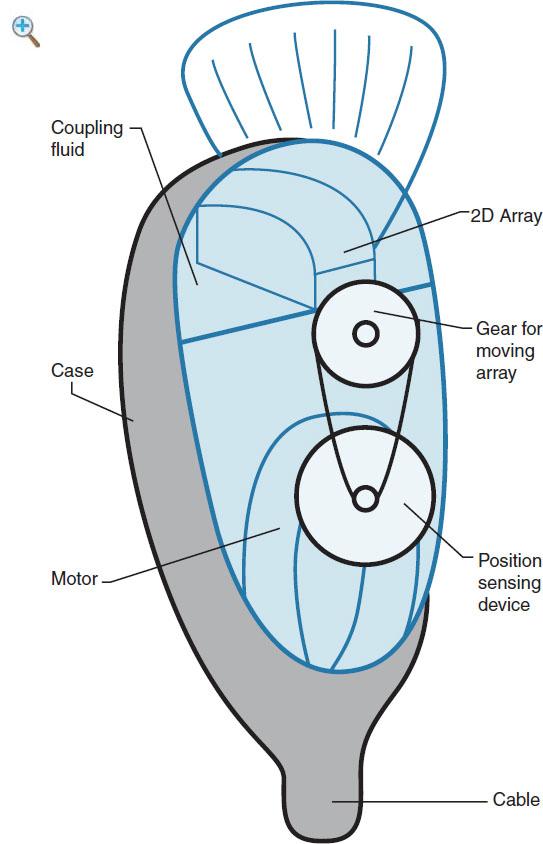

Three-DimensionalVolume Probes

As the name suggests,these are dedicated3Dultrasoundtransducers that are capable of volume acquisition. They are bulky in size and house a 2D array transducer in a casing. The 2D array transducer is surrounded by a coupling gelandisdrivenbyamotorasitsweepsthroughapreselectedvolumeangle. Added to the motor is a magnetic sensing device that coordinates the slices of acquisition with their relative position to each other. This allows an acquisition of volume by maintaining the geometric relationships. Maintaining geometric accuracy is important for spatial orientation and measurements when the information is viewed in multiplanar format or as a volume(Fig.1-7).

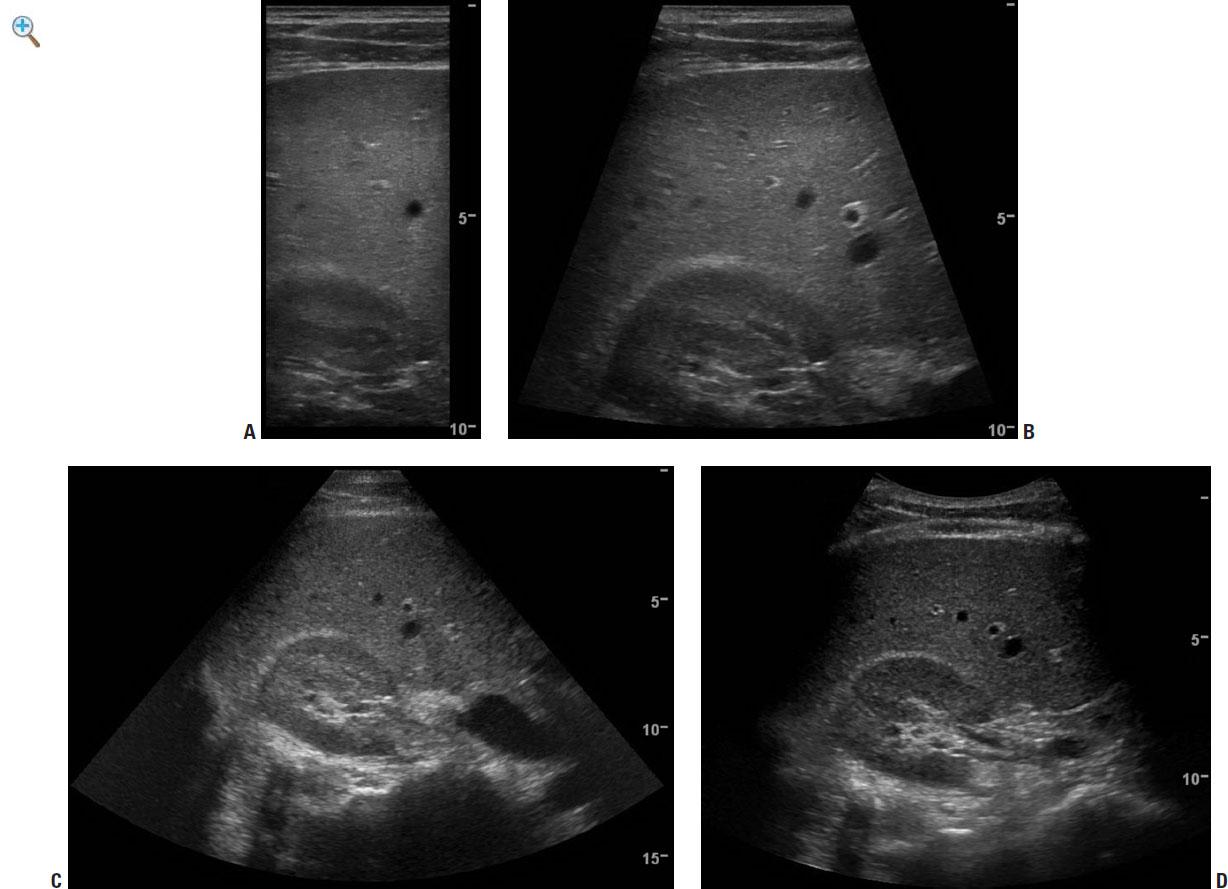

Fig. 1-4 Comparison of standard transducers imaging the liver and kidney. A: Linear array programmed for rectangular imaging In this format, there is excellent resolution throughout the image but a very limited field of view. B: Linear array programmed for sector (trapezoidal) imaging In this format, there is excellent resolution (although slightly less than in the rectangular setting), with a slightly larger field of view. C: Linear array programmed for sector imaging. This format provides the largest field of view with the lowest resolution D: Curved array This provides a compromisewithrelatively highresolutionandarelatively largefieldofview.

Fig. 1-5 Focusing of standard array transducers. A: Illustration of one individual composite sound pulse generated by firing three adjacent elements of a linear array transducer B: The slice thickness is least in the middle of the pulse due to the curvature of the elements. This is fixed and cannot be controlled by the operator. The in-plane focusing is least in the middle of the pulse due to the electronic focusing.

Fig. 1-6 Comparison of conventional array and two-dimensional array. A: Conventional dual scans of the radial artery (cursors) in transverse and longitudinal planes obtained with an operating frequency of 9 MHz. Notice that the artery appears relatively anechoic on the transverse image because in this plane, volume averaging effects are not an issue However, in the longitudinal plane, the slice thickness is greater than the lumen of the vessel producing volume averaging effects with the adjacent soft tissues and echoes within the lumen B: Twodimensional array scans obtained with an operating frequency of 9 MHz. Because theslicethickness canbebetter controlledandreducedwiththis typeof transducer, theluminaldiameter nolonger exceeds thethickness of theslice; this eliminates the volumeaveraginginthelongitudinalplane

TRANSDUCER SELECTION

The selection of a transducer for a given application is dependent on the distance of the object of interest from the transducer. In general, the highest frequency transducer that permits penetration of sound to the target organ should be used. Frequencies of 5.0 or occasionally 3.5 MHz are usually required for evaluation of deeper structures in the abdomen or pelvis. In

obese children and adolescents, frequencies as low as 2.0 MHz may be necessary. For evaluation of superficial structures, 9.0 to 18.0 MHz transducersareusuallyused.

Intracavitary Probes

Recently, transducers have been designed that can be placed within various body lumens. These transducers can be positioned close to the organ of interest, and thus, higher frequencies can be used and higher resolution images can be obtained. The ability to image organs without having to transmit the sound beam through the abdominal wall and intra-abdominal tissues helps to minimize the image-degrading properties of adipose tissue. The overall result is that the images are of much higher quality than those obtained with a standard transabdominal approach. The two most common intraluminal probes are the transrectal and transvaginal transducers (Fig. 18). These are currently used in adults to image the prostate, rectum, perirectalstructures,andfemalepelvicorgans,respectively.Theendovaginal transducerhassomeapplicationsinadolescentgirls(seeChapter13).

Fig. 1-7 Three-dimensional transducer: Illustration shows the basic design of a volume transducer. Inside the outer casing is a two-dimensional transducer that sweeps through a predefined angle to acquire a volume The magnetic sensor is incorporatedinsidetheprobe’s outercase

Endoscopic Probes

Very small transducers have been added to flexible endoscopes to evaluate pathology in the upper and lower gastrointestinal tracts in adults. In the upper gastrointestinal tract, these transducers can aid in evaluating esophageal and periesophageal abnormalities, gastric wall lesions, and perigastric organs. In the lower gastrointestinal tract, these endoscopic probes have been used to evaluate mucosal and submucosal lesions and pericoloniclesions.

Intra-ArterialProbes

Intra-arterial probes are the most recent addition to the armamentarium of intraluminal sonographic devices. They are used to evaluate a variety of abnormalitiesofthearterialwall.

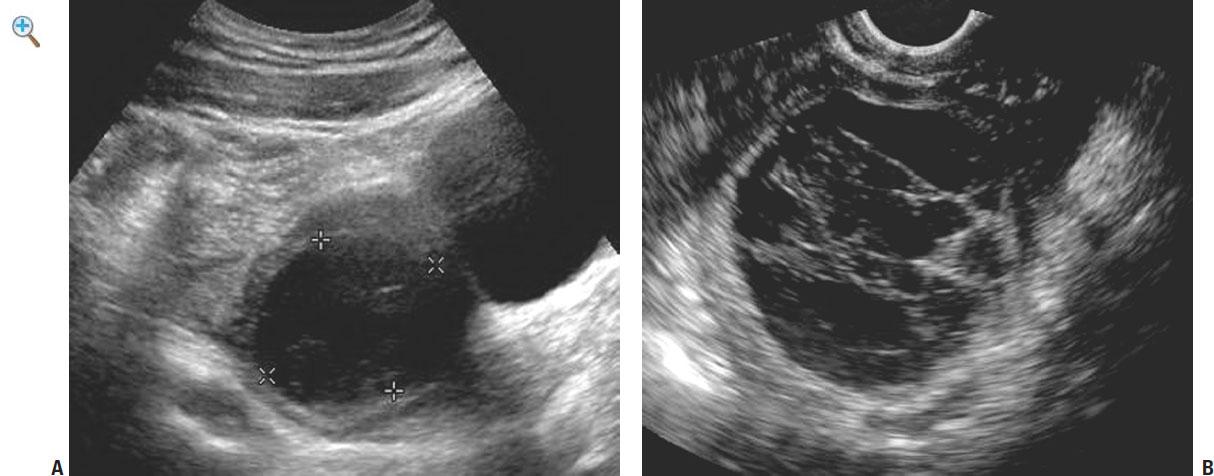

Fig. 1-8 Hemorrhagic ovarian cyst demonstrated with (A) a 35-MHz transducer from a transabdominal approach and (B) a 7.5-MHz transvaginal approach. A nonspecific ovarian cyst is seen on the transabdominal scan The improved resolution on the transvaginal scan demonstrates lacy fibrinous intraluminal membranes typicalofhemorrhagic cysts