Toallthevoyagersinmyfamily

skeggǫld, skalmǫld, skildir ro klonir, vindǫld, vargǫld, áðr verǫld steypisk, mun engi maðr ǫðrum þyrma.

axe age, sword age, shields are shattered, wind age, wolf age, before the world sinks, men will not spare each other.

Vǫluspá,stanza45,aseeressforetellstheendoftheold worldtoOdin

Contents

ListofFigures

Acknowledgments

ANoteonSpellingandPronunciation

1. Introduction: Viking Voyages through History and Archaeology

2. Raiding, Conquering, and Settling Down in Britain: Viking Ways

3. From Subsistence Economy to Political Order: Viking Feasts

4. From Paganism to Christianization: Viking Death and Burial

5. Political Centralization in Denmark: The Viking State

6. Into Marginal North Atlantic Environments: Viking Colonization of Iceland

7. Stories of Vínland: The End of the Viking Horizon

8. Conclusion

Notes

Bibliography

Index

Figures

1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 1.9 1.10 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 2.9 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 3.1 3.2 3.3

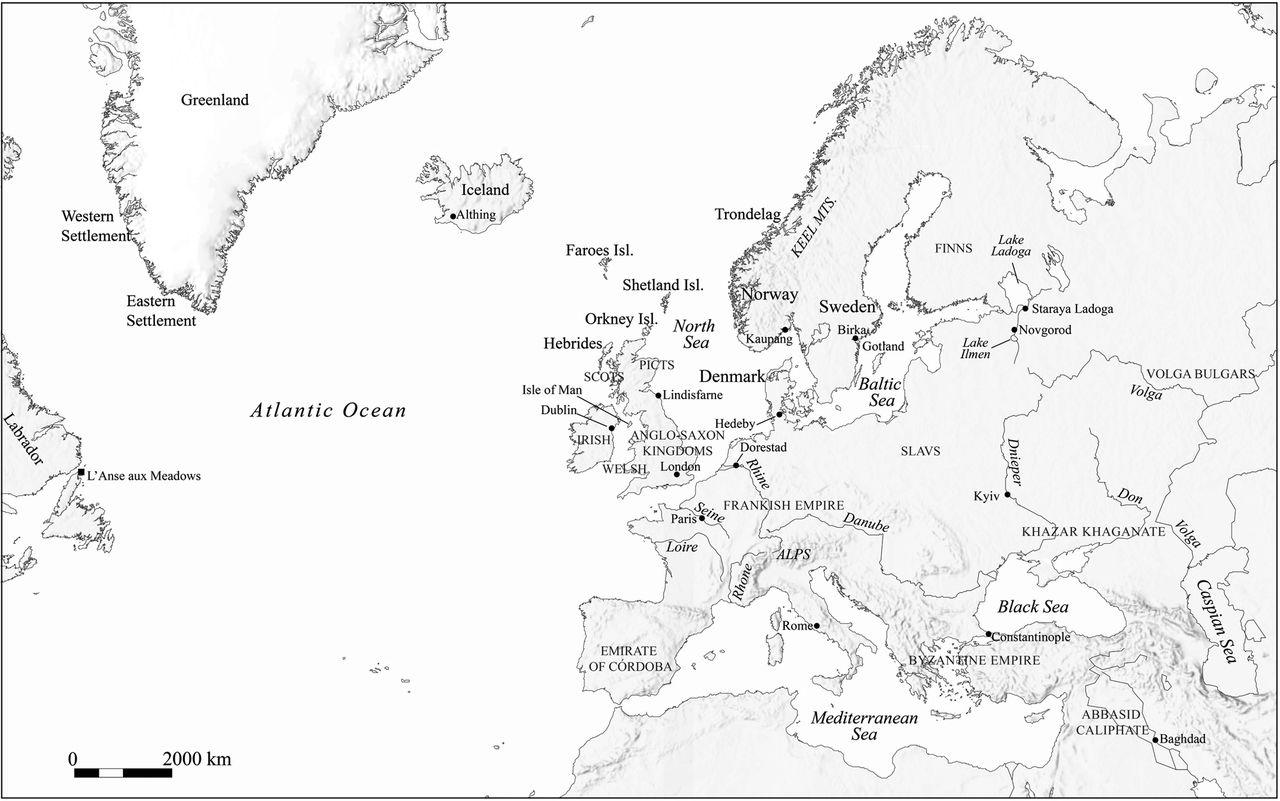

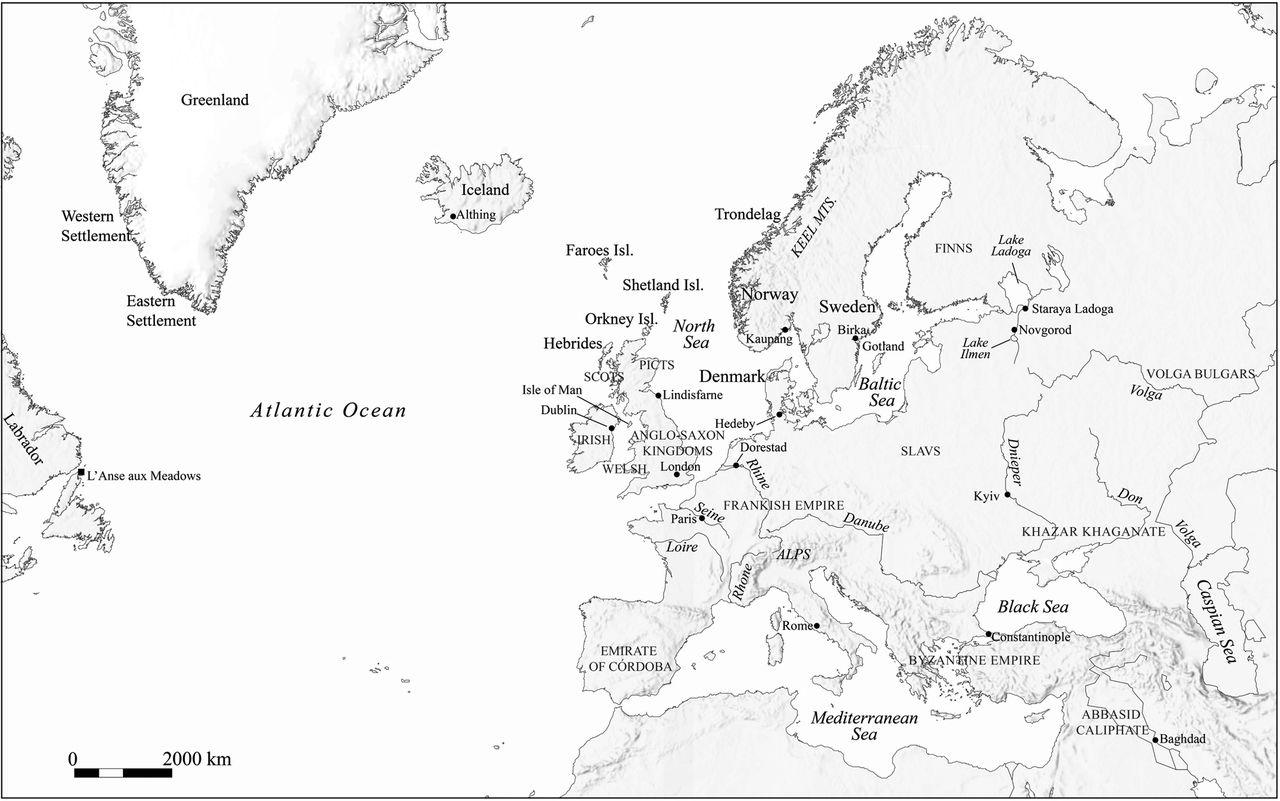

Map of the Viking World

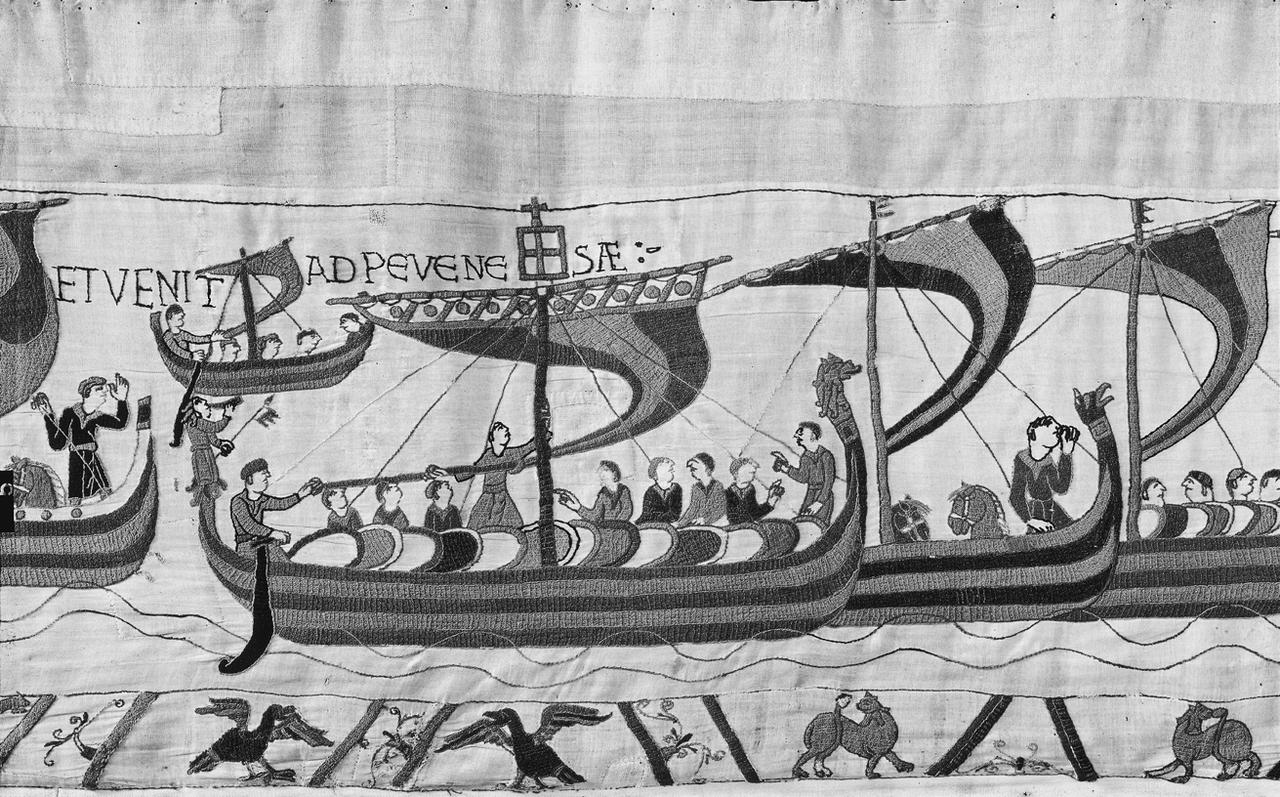

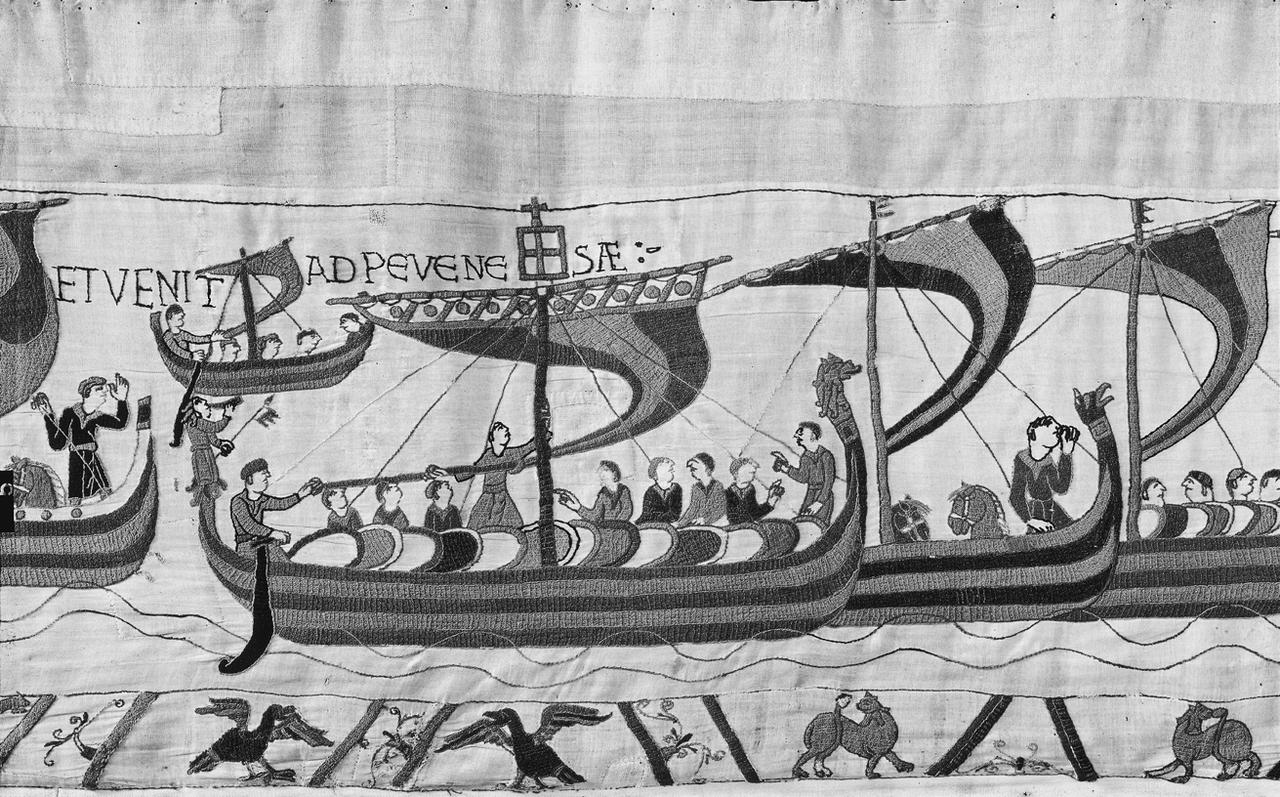

Bayeux Tapestry scene showing William the Conqueror’s fleet c

rossing English Channel

The Piraeus Lion

Runic alphabet, Futhark

The Ramsund Stone

Picture stone from Hejnum-Riddare in Gotland

Aerial photograph of Scandinavia and the Baltic Sea region

Anundshög assembly site in central Sweden

Eyrarland figurine from northern Iceland

Skull fragment from Ribe, Denmark

Map of British Isles in the Viking Age

Lingberg 2 runestone

A portable reliquary shrine

An inscribed slate tablet from the monastery of Inchmarnock

The fortified Viking camp at Repton

Distribution of two Scandinavian place name types in England

Distribution of material culture signatures of Scandinavian settl ement in England

The Brompton Hogbacks

Middleton Cross

Grave marker from St. Paul’s Cathedral in London

Olaf Guthfrithsson’s silver penny minted York

Saint Peter silver penny minted in York

Eirik Bloodaxe’s silver penny minted in York

Alskog Tjängvide I picture stone

Levide Kyrka picture stone

Lillbjärs III picture stone showing a warrior being welcomed wi th a mead horn

3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 3.8 3.9 3.10 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 4.8 4.9 4.10 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 5.8 5.9

Feasters raising a cup to the triskelion symbol on the Sandagår da II picture stone

A figurine of Buddha and an Irish crozier head from Helgö

The elite settlement at Lake Tissø in Denmark

The tenth- to eleventh-century chieftain’s farmstead at Hrísbr ú, Iceland

Excavation of the longhouse at Hrísbrú, Iceland

The tenth- to eleventh-century feasting hall at Hofstaðir in nor thern Iceland

Graph comparing the ratio of cattle to sheep/goat bones from farms in Iceland and Norway

Cremation urn from the North Sea island of Föhr

Lärbro Tängelgårda I picture stone

Map of Kaupang trading site in Norway

Three drawings of Birka Grave Bj 581

Lärbro Tängelgårda IV picture stone

The graveyard associated with the Fyrkat circular fortress

The original appearance of the large Jelling runestone and an aerial photograph of the Jelling site

The Hrísbrú church, Iceland

Reburied human bones at the Hrísbrú church, Iceland

Collingwood’s drawing of “Kjartan’s grave” in the churchyard at Borg, Iceland

Map of Viking Age Denmark

Genealogies of Danish Kings

The Glavendrup monument and runestone

The Large Jelling Stone

Distribution of early Viking Age runestone types across Denma rk

Distribution of runestones from the tenth and early eleventh c enturies in Denmark

Danish Coins from the eighth to the eleventh century

The Danevirke rampart system along the southern border of D enmark

The Trelleborg-type fortresses: Trelleborg, Fyrkat, and Aggersb org

Map of rich graves from the late-tenth century in Denmark

Page from LiberVitaeWinchester manuscript showing Knut th e Great and Queen Emma

St. Knut statue in front of Odense’s St. Knut Cathedral

Map of the North Atlantic

Map of Viking Age Iceland

Map of farm sites of the original settlers of Iceland according t o Landnámabók

Map of the land claims of the landnámsmennwithin Ingolf Arn arson’s original land claim

Thingvellir (the Thing Plains)

Map showing the farms of four chieftains and their supporters in Eyjafjörður

Schematic representation of the Icelandic political organization in the Viking Age after 930

Turf longhouse reconstruction based on a tenth century house excavated at Eiríksstaðir

Hrísbrú chieftain’s longhouse during excavation

Map of Mosfell Valley with primary, secondary, and tertiary far ms

Aerial photograph showing the location of the Hraðaleiði moun d in Mosfell Valley

Map of Greenland, the Arctic, and the northeastern coast of Ca nada

The Skálholt Map

Map of the Gulf of St. Lawrence and surrounding lands

Map of L’Anse aux Meadows, the only verified Norse site in Nor th America

The Okivilialuk Figurine

Norwegian penny from the reign of Olaf the Peaceful found at Goddard, Maine

The Kingittorsuaq Runestone, Greenland

The Kensington Runestone

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to many people and institutions for support and encouragement while I wrote this book. My views on the Viking Age have been formed in great part through collaborations and discussions with friends and colleagues, including Fedir Androshchuk, Terri Barnes, Rhonda Bathurst, Egil Bauer, Marianna Betti, Bjarki Bjarnason, Doug Bolender, Stefan Brink, Jesse Byock, Tara Carter, Colin Connors, Florin Curta, Matthew Delvaux, Jørgen Dencker, Ásdís Egilsdóttir, Bjarni Einarsson, Jackie Eng, Jon Erlandson, Egill Erlendsson, Véronique Forbes, Vaughan Grimes, Magnús Guðmundsson, Greg Mumford, Per Holck, Margrét Hallmundsdóttir, Sice Hansen, Volker Hilberg, Elín Ósk Hreiðarsdóttir, Sven Kalmring, Gunnar Karlsson, Steinar Kristensen, Rúnar Leifsson, Gavin Lucas, Kevin Martin, Steve Martin, Karen Milek, Sarah Morris, Guðmundur Ólafsson, Sarah Parcak, Ben Raffield, Klavs Randsborg, Scott Ridell, Angelos Parigoris, Neil Price, Flemming Rieck, Howell Roberts, David Scott, Dagfinn Skre, Poul Skaaning, Magnús Sigurgeirsson, John Steinberg, Jennica Einebrant Svensson, Óskar Gísli Sveinbjarnarson, Björn Þráinn Þórðarson, Helgi Þorláksson, Guðrún Þráinsdóttir, Ragnheiður Traustadóttir, Nikola Trbojevic, Torfi Tulinius, Mark Tveskov, Claus von Carnap-Bornheim, Tom Wake, Phillip Walker, Bryndís Zöega, and Guðný Zoëga. This book has benefited in tangible ways from my discussions with each of these colleagues.

I want to especially thank my friend and colleague Terri Barnes, who read the entire book manuscript and provided astute suggestions that have notably improved the text. Our discussions of each chapter have been a true pleasure and always filled with good laughs. Also, Jesse Byock, my PhD mentor and my research collaborator for over two decades, has had a profound influence on

my thinking about the sagas and interdisciplinarity. For his support and friendship, I am immensely grateful. From my time at UCLA, John Papadopoulos, Patrick Geary, and Chip Stanish have been lasting intellectual inspirations. My perspective on the Vikings has been formed through spending most of my life living in, visiting, and conducting research in the Scandinavian lands. Denmark and Iceland are second homes for me, and I want to express my gratitude to friends and family, especially Karen and Aksel Hansen, Hans and Birgit Bødker, Claus Jensen and Maria Falden, Lenni Mose, the Pedersen clan, Ólafur Júlíusson, Brooks Walker, Herdís Ólafsdóttir, Pilar Coello, Nicolas Barreiro, Valur Þorvaldsson and Guðrún Sigurðardóttir. At key moments for me, each of you warmed the long Scandinavian winter nights or joyfully extended the summer evenings.

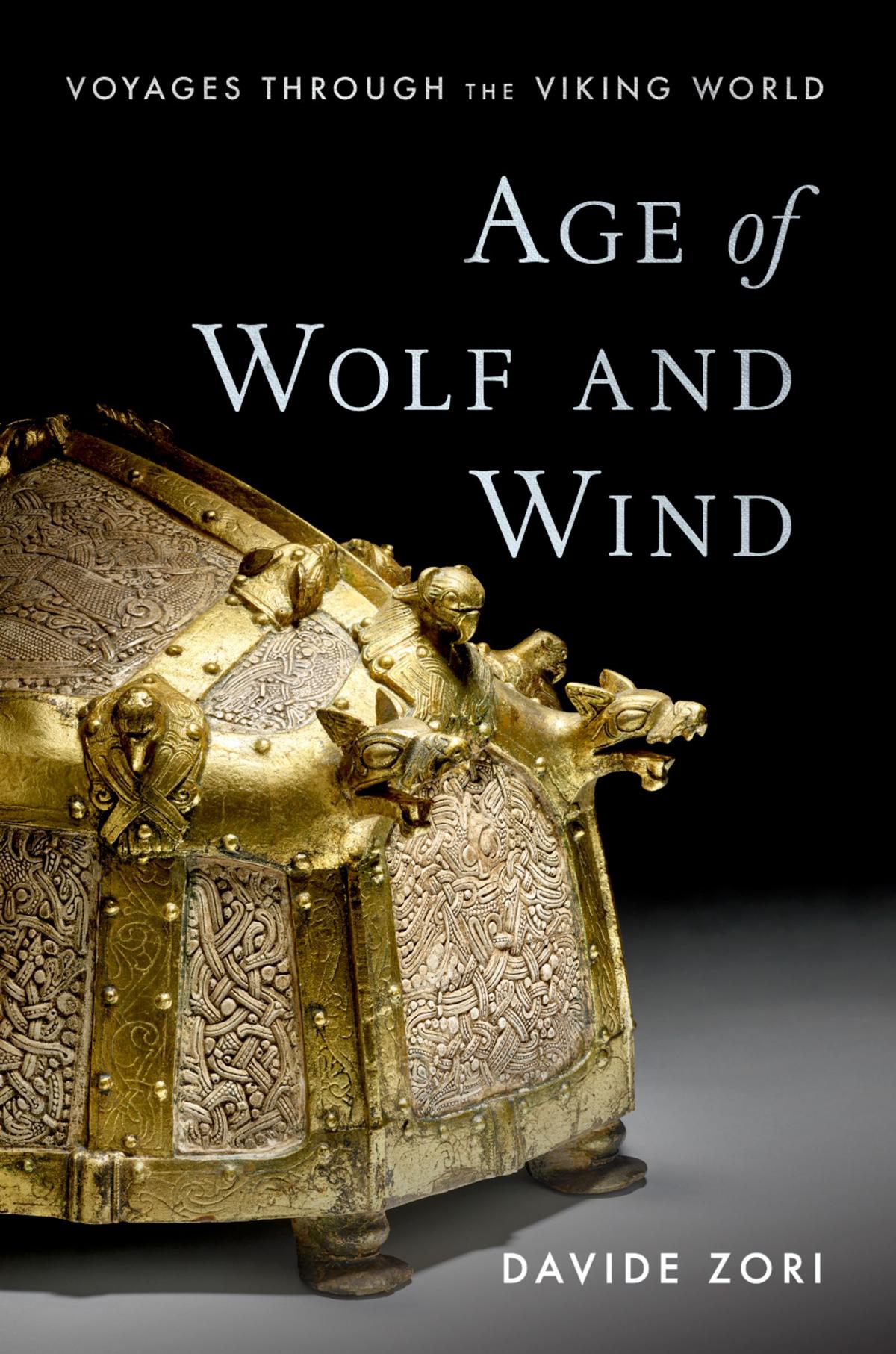

The images and illustrations in this book are many and so are the people and institutions that have granted permission for their use. Roberto Fortuna, photographer at the National Museum of Denmark, took the beautiful photo used for the cover. For institutional permissions to reproduce photographs, I thank the National Museum of Denmark, the Royal Danish Library, the British Museum, the British Library, Museum of London, the National Museum of Iceland, the Swedish National Heritage Board, the National Historical Museums (Sweden), the City of Bayeux, the Corpus of Anglo-Saxon Sculpture, Canadian Museum of History, the Maine State Museum, Compost Creative, Headland Archaeology Ltd., the Minnesota Historical Society, the Viking Ship Museum (Denmark), and the American Numismatic Society. For personal permissions, I am grateful to Gavin Lucas (Hofstaðir map), Pétur Reynisson (Thingvellir photo), Ragnar Børsheim (Tissø digital reconstruction), Neil Price (Birka Grave Bj 581), and Thomas Guntzelnick Poulsen (St. Knut coin).

Publishing with Oxford University Press has been a pleasure. I thank the myriad people at OUP who made this book possible, including the many project managers and copy and image editors. I want to extend my thanks to the anonymous reviewers of the proposal and the finished book draft. Particularly, I thank my editor

at OUP, Stefan Vranka, who believed in this project from the beginning and has guided it to the finish line. Even if we disagree on the ideal caption lengths, we agree about nearly everything else, including the qualities of Italian wines.

This book has been written mostly in central Texas, far away from the Viking world and Italian wines. Here Baylor University has generously supported my work, and I particularly thank my former and current program directors Anne-Marie Schulz, Chuck McDaniel, and Darren Middleton, and the former and current Honors College deans Thomas Hibbs and Douglas Henry for steadfast encouragement and support. My intellectual community here is a source of great happiness, and I particularly thank Jeff Hamilton, Alden Smith, and Jason Whitlark for early and wise council. Always ready for commiserating and sound advice over a beer, my dear friends, Sam Perry and Paul Carron, have many times helped me laugh when I instead wanted to throw up my hands. The Baylor students in my Vikings courses have been tremendous sounding boards. They have repeatedly reconfirmed for me the critical role that teaching plays in the formulation of good questions and lucid explanation of data.

My family has been an unwavering source of strength and encouragement through the writing process. My parents, Åse and Roberto, could not be more supportive, and although they were endlessly incredulous at how long it could take me to finish this book, I hope they will be pleased with the result. For the most profound patience, I thank my wife, Colleen, who keenly read and incisively edited several chapters. After listening to countless hours of musings about the Viking Age and rants at various levels of panic, this book should feel nearly as much yours as mine. To our kids, Lucas and Irene, who sort-of enjoy hearing stories about Vikings and have been forced to voyage across the Atlantic more times than they would care to count in pursuit of archaeology, thank you for not protesting too much; at least we didn’t have to do it in open wooden ships.

A Note on Spelling and Pronunciation

Many people and places from across the Viking world are discussed in this book, including especially names of archaeological sites and personal names from various cultures in Europe, Asia, the North Atlantic, and the Mediterranean region. Standardization in spelling of Old Norse—the language of the Vikings—is challenging, and consistency is nearly impossible. There was no uniformity for spelling in the Viking Age, nor in the letters in the Scandinavian runic alphabet, which varied regionally and changed over time. The various languages used in the texts, both ancient and modern, also pose significant challenges. To take just one example: one of the most famous Viking Age kings is Knut the Great. His name is written in many different forms in modern scholarship ranging from Old Norse versions with or without nominative endings to those that are anglicized or use modern Scandinavian spelling, resulting in many variations: Knútr, Knút, Canute, Cnut, Knut, Knud, and Knútur. For simplicity, this book uses the anglicized Old Norse version Knut without accents. As a rule, I aim for readability and consistency in English. Therefore, names and places are often anglicized in the main text, especially names that are familiar to the reader. For instance, I write Odin and not Óðinn, and Thor rather than Þórr. The original language of direct quotes in Old Norse, Latin, Anglo-Saxon (Old English), and all the modern Scandinavian languages is provided in the endnotes.

A word about pronunciation is useful as some readers will be unfamiliar with the letters used to write Old Norse and the modern Scandinavian languages. Most scholars prefer to follow modern Icelandic pronunciation for Old Norse even though differences existed in space and time. For instance, the sounds of the letters ǫ and ø letters were distinguished from each other in Old Norse in the

Middle Ages before converging into the single ö letter, which has since been used in Icelandic and Swedish, but not in Danish and Norwegian, where the single ø is retained. The ä/aa/å vowel, which emerged from the Old Norse long a (á), varies a bit more in pronunciation in the modern Scandinavian languages but the Icelandic pronunciation is close to the ou in house. The chart below offers the English sound equivalents for the modern Icelandic pronunciations commonly used for Old Norse.

Á á ouin house

É é yein yellow

Í í eain ear

Ó ó owin slow

Ú ú ooin cool

Ý ý eein beet

Þ þ (“thorn”) soft thas in thin

Ð ð (“eth”) hard thas in father

Æ æ, Œ œ ias in Nile

Ø ø, Ö ö, Ǫ ǫ ooin book

For personal names from the ancient sources, I anglicize unfamiliar letters and drop accents for ease of reading, while often giving the original in parenthesis at the first mention of a name. Þ/þ is replaced with th, while Ð/ð is anglicized as d, such that the female names Þorgerður and Þórdís are written as Thorgerdur and Thordis. I also drop the final consonants of many male names, which are actually only the nominative case ending, as in for example the double n in Óðinn, and more commonly the final -r, as in Knútr. Names of modern scholars are retained in their native Scandinavian forms for bibliographical accuracy. Viking Age people were often given nicknames based on appearances, characteristics, and accomplishments. I retain these nicknames, such as Harald Bluetooth and Eirik Bloodaxe, to help distinguish the many Haralds and Eiriks of the period.

Finally, for place names, which the reader often still needs to find on modern maps, I retain the spellings used in their respective modern countries. So, in Iceland for instance, I will refer to Hrísbrú and Borgarfjörður, while in Denmark we will encounter Tissø and

Toftegård. At times, the acute accents can crucially change the meaning of a word, such as for example in Vínland (Wine-land) versus Vinland (Pasture-land). In these cases, the accents are preserved. A few larger geographical areas, besides modern countries, are given in their well-known anglicized form, such as Jutland rather than Jylland.

1 Introduction

Viking Voyages through History and Archaeo logy

Viking Voyages

The story of the Vikings is one of voyages. In the Viking Age, Scandinavian voyagers from today’s Denmark, Norway, and Sweden encountered new people and novel landscapes with an unprecedented intensity. The movement of people brought transfers of ideas, sharing of technologies, trade in material goods, intermarriage, and warfare. The Viking Age (c. 790–1100) is primarily represented in popular culture as a violent age, and it was. It was also much more. Vikings were farmers, raiders, traders, and settlers. Most Viking Age Scandinavians probably would not have thought of themselves as “Vikings.” The word víkingdid exist at the time, but it referred strictly a to sea-borne raider, essentially a pirate. It was an occupation, and it could be seasonal work, a multi-year engagement, and at times a lifetime commitment. In fact, Scandinavian víking raiding parties could and did incorporate peoples from other linguistic, ethnic, and cultural groups. Nonetheless, for convenience and because of broadly understood conventions, scholars often use the term Vikings to refer broadly to Viking Age Scandinavians.

Like most people in most ages, Viking Age Scandinavians were opportunists looking for ways to better their own situation in life, and that of their family and offspring. The overwhelming majority of

people were farmers, but at an unprecedented scale, leaving the farm for other economic activities became possible and lucrative. People could pursue craft production or trading in the growing urban centers or get aboard the increasing numbers of ships leaving the native shores to trade at foreign ports, or if the centers of wealth concentration—monasteries and trading sites—seemed vulnerable, then they could raid. As the Viking Age progressed, permanent migration to unpopulated or newly conquered lands opened new venues for Scandinavians seeking to better their fortunes. Scandinavians struck out far beyond the western extent of any European travelers, settling the North Atlantic islands of Iceland and Greenland and reaching the eastern shores of North America. To the modern reader, these voyagers seem perhaps overly intrepid, boarding open wooden boats to cross the North Atlantic and travel into the unknown. This is also why the Vikings continue to fascinate us, because their compelling stories connect with the universal human desire for exploration and adventure.

The Viking Age was the most dynamic period in the pre-modern history of Scandinavia. Scandinavians have long considered it a Golden Age in which their ancestors’ impact on the world extended far beyond the region’s borders. Inter-regional connections stimulated trade as Scandinavians traveled farther from their homelands. At the start of the Viking Age, Scandinavia had no urban centers. When the age ended, cities had emerged as the centers of trade and government administration. Economic exchange at the start of the Viking Age took the form of barter, while the end of the Viking Age had seen the emergence of state-controlled currencies on the model of coins used in Western Europe. Christianity arrived as ideas were exchanged in the nascent urban centers. At the start of the Viking Age, Scandinavia was divided into chiefdoms and petty kingdoms. At its close, the states of Denmark, Norway, and Sweden emerged united under single monarchies. As we shall see in the chapters ahead, the turn of the millennium around 1000 was a time of transition that saw tremendous changes in Scandinavia in urbanization, monetization of the economy, Christianization, formation of powerful unified states, and comprehensive

Europeanization. When these factors took hold thoroughly by the end of the eleventh century, Scandinavia became fully incorporated into Christianitas, as Christian Europe was known, and the Viking Age came to a close.

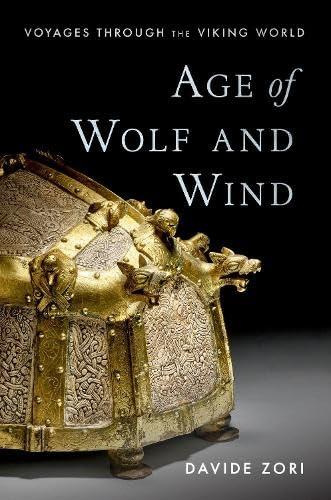

The Vikings had a tremendous impact on the peoples and lands they encountered in their maritime movements along coastlines and along the rivers of Eurasia. The Viking ship, which was the culmination of centuries of native Scandinavian innovations, gave them privileged access to these maritime and riverine superhighways. These fast, shallow-drafted, and sturdy ships gave them advantages everywhere they traveled. Scandinavians played key roles in connecting far-flung regions into a Viking-dominated trade system, sometimes called the Northern Arc, which connected Western Europe to the Middle East and the western ends of the Silk Roads leading east to China. This trade system was even more important because the trade across the Mediterranean Sea, once overseen by the Roman Empire, had largely collapsed after the fall of the Western Roman Empire and the rapid Arab conquests of the Middle East and North Africa. The Mediterranean was split between polities with diverse cultures, languages, and religions. Trade across the Mediterranean certainly did not disappear, but it was much decreased. The Vikings filled the void by redirecting trade through the river superhighways of Russia and Ukraine—especially the Dnieper and the Volga Rivers—and across the Baltic Sea to the emergent Scandinavian trading centers, and on to Britain, Ireland, and Francia (Figure 1.1). The vast numbers of coins from the Islamic Caliphates that have been found in Scandinavia attest to the strength of this trade. This trade had its dark side too: one of the most important commodities that Scandinavians brought south to the large urban centers of Constantinople and Baghdad were slaves.

Figure 1.1 The Viking World

Source: map by author

The traditional historical date for the beginning of the Viking Age is taken from the raid on the English monastery of Lindisfarne in 793, which sent shock waves across Western Europe. Although this does not appear to have been the first Scandinavian raid in Britain, letters exchanged between appalled clerics in Britain and Francia show that this raid had a reverberating impact. In one of the most famous of these letters, written by the Anglo-Saxon scholar Alcuin from the court of Charlemagne to King Æthelred of Northumbria, we find evidence of the shock that most contemporaries felt.

Behold, we and our forefathers have inhabited this most beautiful land for almost three hundred and fifty years and never before has such terror appeared in Britain as we have now suffered from a pagan people; nor was it thought that such an incursion across the sea was possible. Behold St. Cuthbert’s church spattered with the blood of God’s priests and deprived of its holy ornaments. Britain’s most venerable site has been left as prey to the pagans.1

With the help of their ships, recently equipped with a sail, Scandinavians could now surprise any community in Britain by crossing the North Sea directly instead of hugging the European continental coast to cross at the English Channel. The late fifth- to sixth-century Anglo-Saxon invasions of England had been accomplished in row boats without sails. The threat from the pagan lands was transformed.

When Vikings emerged from the sea to sack Lindisfarne, what is today England was divided into separate and often warring kingdoms. In the late eighth century, there were seven kingdoms, known as the heptarchy: Wessex, Essex, Sussex, Kent, East Anglia, Mercia, and Northumbria. By the early ninth century, however, Wessex had absorbed Essex, Sussex, and Kent. Viking attacks and conquests over the next half century would eliminate East Anglia, Mercia, and Northumbria, leaving only Wessex. Forced by Vikings to rearm, refortify, and reform, the kingdom of Wessex would eventually reconquer these lands and create a unified kingdom of England. In this way, the Viking Age was the crucible in which the English state was formed. In the areas of Scotland’s northern and western islands—the Hebrides, Orkneys, and Shetlands—the Vikings dominated local populations, and the Norse culture and language took over. In Orkney, Shetland, and some areas of mainland Scotland, people spoke a Scandinavian language called Norn until the nineteenth century.

Vikings raided in Ireland by 795 and began to settle there permanently in the early 800s. The Viking story in Ireland was different from the rest of the British Isles. Here, among decentralized Celtic chiefdoms, and in the absence of any urban centers, Vikings became intimately involved in the process of urbanization and the fostering of inter-regional trade. A nationalistically charged debate still simmers about whether the Vikings started the first towns in Ireland. What can certainly be said is that there is a direct correlation between the arrival of the Vikings and the appearance of the first Irish towns, which were all coastal and located on rivers. Many of these towns have Norse names: Waterford (Veðrarfjörðr), Wexford (Viegsfjörðr), and Limerick (Hlymrekr). These early Irish

towns, especially Dublin, have yielded Scandinavian burials of both males and females, reminding us that Viking migrants were not just men. The Scandinavian influx was coastal, and little archaeological evidence of Scandinavian settlement exists internally in Ireland. Nonetheless, DNA studies show that up to 20 percent of the modern Irish population has Norwegian ancestry, deriving presumably from a sizable influx of Scandinavians in the Viking Age.2 The intermixing of populations in Ireland resulted in a rich hybridized culture, referred to as Hiberno-Norse.

In contrast to most other Viking ventures, the settlement of the large North Atlantic islands was a peaceful process, as there was no one there to raid, fight, or conquer. Instead, Viking Age Scandinavians brought their traditional ways of subsistence and political organization to these remote islands. The Scandinavian seafarers’ encounter with these islands at the far margins of the known world are just as central to the story of the Vikings as are their violent encounters with Northumbrian monks. Vikings probably discovered the Faroe Islands on their voyages from Norway to Britain, setting in motion the island-hopping Scandinavian settlement of the North Atlantic that followed a pattern of accidental discovery, purposeful exploration, and planned settlement. The Faroes were quickly settled in the mid-ninth century. Iceland was discovered soon after, and permanent settlers began arriving around 870. By 930, the extensive lands of Iceland had all been claimed by Scandinavians from the homelands and Vikings retiring from their more violent activities in the British Isles. Island-hopping farther across the North Atlantic Ocean, Vikings, who are usually called Norse in this region, settled within the sheltered fjords on the southwestern coast of Greenland in the 980s. Less than twenty years later, the Norse sagas tell us that mariners blown off course on their way to Greenland discovered the eastern shores of the Americas. Irrefutable archaeological evidence of at least one Viking Age Scandinavian settlement on Newfoundland, Canada, now validates these old stories. Through the Viking Age, these islands of the North Atlantic remained in direct contact with the Scandinavian homelands. But as

the large-scale people movements of the Viking Age came to an end, the contact with these distant colonies dwindled. Icelandic culture continued to thrive, preserving for us some of the most significant literature of the Middle Ages in the Icelandic Sagas, but the more remote outposts in Greenland declined in increasing isolation and disappeared sometime before 1500.

On the European continent, Vikings had dramatic impacts on coastal regions of what is today Germany, France, Netherlands, and Belgium. The Carolingian dynasty of the Franks, who ruled these lands, had built Western Europe’s most powerful medieval state. After striking a mutually beneficial alliance with the pope, the most famous Carolingian king, Charlemagne, had been crowned Roman emperor and king of the Lombards in 800. Especially after the end of Charlemagne’s strong reign, no places on the coast, or along the European river systems of the Rhine, Seine, Loire, and Garonne, were safe from Viking incursions. The numbers of communities, towns, and cities that endured Viking attacks is staggering. It puts the period into perspective to remember that each of the brief historical mentions of raids represents great suffering as people were violently dragged from their homes, killed, raped, or enslaved, while their wealth was stolen, and their lands and houses burned. It is sometimes said that the Vikings were no more violent than other peoples of the Middle Ages, and there is some truth to that. But they were certainly not less violent. The non-Christian Vikings, who depended on raiding and slaving for wealth accumulation, did not have any of the ideological taboos in dealing out this type of violence on peaceful Christian sites. Some scholars have gone as far as to suggest that Viking raids represented a religiously motivated vengeful assault on Christian sites. But their frequent attacks on monasteries is more likely to have been an opportunistic strategy targeting places of great wealth inhabited by folks that were relatively less capable of self-defense.

In the ninth-century heyday of Viking activity on the European Continent, Viking fleets that had established permanent bases at the mouths of the great French rivers would have heard stories of even greater wealth farther south. From these bases, Vikings entered the

Mediterranean Sea through the Straits of Gibraltar. Scandinavian sagas of mythic proportions about men like Bjorn Ironside (Bjǫrn Járnsíða) include much fantasy, but their grounding in a historic voyage from 859 to 862 is substantiated by Frankish annals and accounts in Arab sources from North Africa and the powerful Muslim Caliphate of Córdoba that controlled the Iberian peninsula. The Viking fleet, said to number sixty-two ships, raided Spain and North Africa, capturing the Moroccan town of Mazimma, where wealthy citizens were ransomed. The fleet continued to southern France and sacked Pisa in central Italy, but as they continued east, the corroborating Frankish and saga sources become less reliable. We are left with a particularly colorful account of a siege of a town in Italy that Bjorn Ironside and his partner Hastein believed to be Rome. The late tenth-century Norman historian Dudo of St. Quentin resorts to a storytelling cliché when he recounts how Hastein faked his death, complete with a pre-death conversion to Christianity, in order that he might be allowed into the city for Christian burial. Once his coffin had been carried through the city gates and Mass had been said over his body, Hastein jumped out fully armed and led the Vikings in a surprise attack. The ruse worked and the town was sacked, but only thereafter did the Vikings realize that the town they had sacked was the provincial city of Luni.3 Later Norman historians, like William of Jumièges (mid-eleventh century), retold this story and applied Hastein’s trick to stories of other daring siege breakers. Several sagas, including TheSaga of Ragnar Lodbrok and His Sons and TheTaleofRagnar’sSons, also recount the story of the capture of Luni, albeit without Hastein’s elaborate ruse and without the Vikings’ implausible misidentification of Luni as Rome. Stories such as these, even if based on memories of real journeys, cannot of course be trusted in their details, and no archaeological evidence has been recovered that can be tied directly to the voyage and Mediterranean raids of Bjorn and Hastein.

By the tenth century, the French and German inheritors of the Frankish Empire were mounting increasingly effective resistance against the Vikings. As fortification of towns and bridges, as well as

reorganization of local defenses and navies, made traditional Viking activities more difficult, some Scandinavians looked for other opportunities elsewhere while others tried to make deals with local rulers to settle. The West Frankish king, Charles the Simple, pursuing a policy of appeasement, granted land to a Viking leader by the name of Hrolf (Rollo in Latin sources) around the mouth of the Seine River in 911. In return for this grant of land, Hrolf swore fealty to the French king and promised to defend the mouth of the Seine from incursions by other Vikings. Hrolf’s descendants would forge a powerful state here that became known as the Duchy of Normandy, or Duchy of the Northmen. The impact of this geographically small polity was extraordinary. Hrolf’s descendent William the Bastard became William the Conqueror after his Norman Conquest of England in 1066. Other Norman knights, operating as mercenaries in the central Mediterranean in the decades after the Norman Conquest, would forge for themselves a kingdom on the island of Sicily. The Normans who conquered England and formed the kingdom of Sicily were French speakers but retained cultural aspects of their Scandinavian background, including a rich tradition of sagalike storytelling and, as we see on the Bayeux Tapestry, which depicts William’s victory at the Battle of Hastings, ships of the Viking tradition (Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2 William the Conqueror’s fleet sailing across the English Channel during the Norman Invasion of 1066 as depicted on the Bayeux Tapestry (c. 1075). The Normans, or “North Men,” spoke French but had Scandinavian ancestry and sailed across the channel in ships built in the Scandinavian tradition.

Source: detailofthe Bayeux Tapestry courtesy ofthe City ofBayeux

The Vikings’ effect on the Carolingian Empire was disruptive and destructive of imperial control, contributing in the longer term to the splintering of the regional political order into feudal lordships. During Charlemagne’s reign (768–814), Carolingian military strength held Viking attacks mostly in check, but the situation began to deteriorate already in the reign of his son, Louis the Pious (814–840), and especially after Charlemagne’s grandsons—Lothar, Charles the Bald, and Louis the German—divided the Frankish Empire into three kingdoms at the Treaty of Verdun in 843. These internal troubles, exacerbated by the Viking assaults, eroded centralized power and revealed the inability of the Frankish kings to protect local populations. Local lords increasingly assumed this role as provincial protectors, building castles and forming their own private armies to