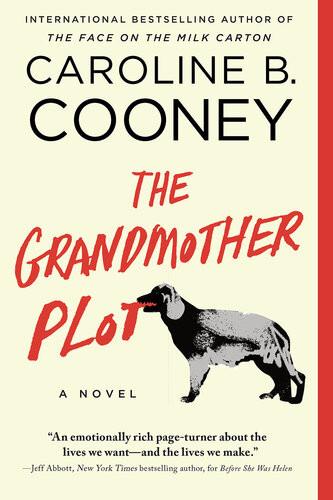

Gestural Imaginaries

Dance and Cultural Theory in the Early Twentieth Century

L ucia R up R echt

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

© Oxford University Press 2019

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Ruprecht, Lucia, 1972– author.

Title: Gestural imaginaries : dance and cultural theory in the early twentieth century / Lucia Ruprecht.

Description: New York : Oxford University Press, 2019. | Series: Oxford studies in dance theory | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018040520 (print) | LCCN 2018053236 (ebook) | ISBN 9780190659394 (updf) | ISBN 9780190659400 (epub) | ISBN 9780190659417 (oso) | ISBN 9780190659370 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780190659387 (pbk.: alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Modern dance—Europe—History—20th century. | Choreography—Europe—History—20th century. | Gesture in dance.

Classification: LCC GV1783 (ebook) | LCC GV1783 .R79 2019 (print) | DDC 792.8094—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018040520

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Paperback printed by WebCom, Inc., Canada

Hardback printed by Bridgeport National Bindery, Inc., United States of America

This possibility of bodies to be several things at the same time is a precondition for the imaginary, and thus for the development of gestures and dance.

Jeroen Peeters, Through the Back: Situating Vision between Moving Bodies

Imponderable evidence includes subtleties of glance, of gesture, of tone.

Ludwig Wittgenstein, Philosophical Investigations

Every age had its own gait, glance, and gesture.

Charles Baudelaire, The Painter of Modern Life

CONTENTS

List of Figures ix

Series Editor’s Foreword xi

Acknowledgments xiii

List of Abbreviations xv

Prologue: Inaugurating Gestures—Le Sacre du printemps 1

Introduction: Gestural Imaginaries 23

1. A Second Gestural Revolution and Gesturing Hands in Rainer Maria Rilke, Auguste Rodin, Mary Wigman, and Tilly Losch 51

2. Gestures of Vibrating (Interruption) in Rudolf von Laban, Mary Wigman, and Walter Benjamin 71

3. Conducts and Codes of Gesture in Walter Benjamin and Franz Kafka 87

4. Gestural (In)visibility in Béla Balázs and Helmuth Plessner 107

5. Gestures between Symptom and Symbol in Aby Warburg and Sigmund Freud 125

6. Gestures between the Auratic and the Profane: Niddy Impekoven’s and Franz Kafka’s Reenactments of Liturgy 151

7. Gestural Drag: Baroquism and Modernist Minstrelsy in Alexander and Clotilde Sakharoff 169

8. Floral Pathochoreographies: Mime Studies by Harald Kreutzberg, Alfred Döblin, and Jo Mihaly 193

Epilogue: Intermitting Economy, Opening Futurity 221

Notes 229

Bibliography 287

Index 313

FIGURES

1.1 Hilde Doepp in Dreams and Masks, photographed by Charlotte Rudolph 57

1.2 Mary Wigman, Hand Study, photographed by Albert Renger-Patzsch 63

1.3 Arm and Hand Studies, photographed by Charlotte Rudolph 64

1.4 Arm and Hand Studies, photographed by Charlotte Rudolph 65

1.5 Tilly Losch in Dance of the Hands, photographed by Emil Otto Hoppé 69

5.1 Birth of the Baptist by Domenico Ghirlandaio 131

5.2 Panel 47 from Aby Warburg’s Mnemosyne Atlas 133

5.3 Moses by Michelangelo 144

5.4 Drawings of Michelangelo’s Moses by Sigmund Freud 145

6.1 Niddy Impekoven in Bach Dances, Atelier d’Ora/Benda 154

6.2 Niddy Impekoven in Bach Dances, Atelier d’Ora/Benda 155

6.3 Niddy Impekoven in Bach Dances, Atelier d’Ora/Benda 156

6.4 Niddy Impekoven in Bach Dances, Atelier d’Ora/Benda 157

7.1 Alexander Sakharoff in Pavane royale 177

7.2 Alexander Sakharoff in the Louvre in front of Hyacinthe Rigaud’s portrait of Louis XIV 182

7.3 Alexander Sakharoff in Pavane royale, photographed by Masao Horino 183

7.4 Clotilde Sakharoff in Chanson nègre, photographed by René Gilbert 190

7.5 Clotilde Sakharoff in Chanson nègre, photographed by Masao Horino 191

8.1 Jo Mihaly in Vision of War 201

8.2 Jo Mihaly in Vision of War 202

8.3 Jo Mihaly in Vision of War 203

8.4 Harald Kreutzberg in Three Mad Figures, photographed by Hans Robertson 206

8.5 Harald Kreutzberg in Three Mad Figures, photographed by Hans Robertson 207

8.6 Jo Mihaly in Flower in the Backyard 217

8.7 Jo Mihaly in Flower in the Backyard 218

8.8 Jo Mihaly in Flower in the Backyard 219

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This book is a conversation with many people, but without two of them, it would not exist in its current shape: Gabriele Brandstetter, who hosted my Humboldt Fellowship at the Institute of Theater and Dance Studies at Free University Berlin from 2013 to 2015, provided a wonderfully stimulating research environment, and offered feedback and presentation space, mentorship, friendship, and support; and Mark Franko, who published an early version of one of the chapters, agreed to include the book in the Oxford Studies in Dance Theory series, invited me to teach and present at his department in Philadelphia, and instigated intellectual exchange that sparked my thinking over the past few years. I am immensely grateful to both of them. There are more friends and colleagues whose comments and advice were instrumental. Susan Manning was an enthusiastic interlocutor from the start, continuing our conversation that began many years ago. Susan Leigh Foster’s suggestions steered me into productive directions. My engagement with Weimar dance was triggered in discussions with Kate Elswit, first as her supervisor, then as colleague and friend; her energetic presence is visible on the pages of this book. Carrie Noland, Rebecca Schneider, Astrid Deuber-Mankowsky, Michael Minden, Alexander Schwan, and Jonas Tinius contributed fabulous papers to the symposium on the ethics of gesture that I organized at Emmanuel College, Cambridge, in 2016; the thinking that went on during this day has marked my work on Gestural Imaginaries. My profound thanks are due to Andrew Webber, as always, for his comments on selected book chapters, his mentorship, and his friendship. Katja Haustein and Marie Kolkenbrock sent perceptive remarks on a chapter-in-progress. Barry Windeatt shared literature on gesture. Christopher Johnson provided a warm welcome to his gesture workshop at the Warburg Institute in December 2016. I am grateful to colleagues and friends who invited me to present aspects of my research on this book at conferences and lecture series in Germany, the United Kingdom, Ireland, and Poland: Carolin Duttlinger, Sabine Huschka, Benjamin Schofield,

Clare Foster, Yvonne Hardt, Nikolaus Müller-Schöll, Sabine Egger, Nina Tolksdorf, Mona de Weerdt and Andreas Schwab, Georgina Born, Christopher Haworth, and Jonas Tinius, Deborah Holmes and Heide Kunzelmann, and Joanna Szymajda and Wojciech Klimczyk.

I would like to extend my thanks to the director and staff at Deutsches Tanzarchiv Köln, Frank-Manuel Peter, Donatella Cacciola, Bettina Hesse, Christel Dreiling, and Garnet Schuldt-Hiddemann; to Hedwig Müller at the Theaterwissenschaftliche Sammlung Schloss Wahn; and to the staff at the archives of the Akademie der Künste and the Lipperheidesche Kostümbibliothek, Berlin. Earlier versions of two chapters have been published elsewhere: chapter 2 appeared in Dance Research Journal 47, no. 2 (2015), and parts of chapter 3 in Franz Kafka in Context, edited by Carolin Duttlinger (Cambridge University Press, 2017). I wish to thank the editors of these publications for permission to reprint here. I am grateful to the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation for offering me a Fellowship during which I began my research toward this book. At Cambridge I owe thanks to the directors of the German Endowment Fund and the Schröder Fund, and to Emmanuel College. At Oxford University Press, heartfelt thanks go to my anonymous readers, to Norman Hirschy and Lauralee Yeary, and to Christina Nisha Paul.

Finally, I wish to thank my parents and mother-in-law, for their unstinting help with the running of life between work and family. Above all, I wish to thank Jens and Lisa Antonia.

ABBREVIATIONS

AdK Akademie der Künste Berlin

AS Rancière, Aisthesis

DTK Deutsches Tanzarchiv Köln

GS Benjamin, Gesammelte Schriften

IS Castoriadis, The Imaginary Institution of Society

LC Plessner, The Limits of Community

MM Freud, The Moses of Michelangelo

NG Agamben, “Notes on Gesture”

OT Benjamin, The Origin of German Tragic Drama

PH Plessner, “Zur Geschichtsphilosophie der bildenden Kunst seit Renaissance und Reformation”

PM Adorno, Philosophy of New Music

SH Freud and Breuer, Studies in Hysteria

SP Rivière, “Le Sacre du printemps”

SW Benjamin, Selected Writings

VM Balázs, “Visible Man or the Culture of Film”

Where not otherwise stated, translations of passages from Benjamin’s Gesammelte Schriften and of other texts of which no official translations exist are my own.

Prologue

Inaugurating Gestures— Le Sacre du printemps

On 29 May 1913, Le Sacre du printemps (The Rite of Spring) premièred at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées in Paris. The piece is nearly plotless: an archaic community gathers to conduct its annually recurring fertility cult, culminating in the selection and sacrifice of a young girl who dances herself to death. The collaboration between composer Igor Stravinsky, choreographer Vaslav Nijinsky, painter and archaeologist Nicholas Roerich, and impresario Sergey Diaghilev created a scandal. Staged in a recently finished theater that had been built for the purpose of providing contemporary trends in music and performing arts with a dedicated space, the performance famously ended in riot. Yet once the sensationalist waves of the social event had receded, it was hailed as the first post-Impressionist masterwork.1 Soon it would become one of modernism’s most powerful legends. Combining a viscerally brutal score with primitivistic stage décor and a new language of movement, Sacre touched a nerve among the excitable cultural elite. Despite its enduring impact, it was performed only nine times in its first iteration: after five evenings at the Champs-Élysées, it was shown four times at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, in London, where the curtain fell after a final performance on 23 July 1913. Nijinsky never notated the choreography. It is well documented, however, that he was adamant to continue on his course of radical modernism against the will of his impresario.2 When on tour in South America during autumn of that year, he announced his surprise marriage to Romola de Pulszky. Diaghilev dismissed his star dancer from the Ballets Russes; half a year later, the First World War broke out, severely affecting the company’s operations. Nijinsky was interned in Hungary and unable to continue work with the troupe that he had, by this point, founded. He returned to the Ballets Russes a couple of times for performances in North America and Spain before retreating, in 1919, into

an increasingly private life marked by mental illness. On 15 December 1920, Sacre premièred again at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées, in a new staging with choreography by Léonide Massine.3 It was this version that finally entered the repertoire of the Ballets Russes, the first in a long row of restagings and adaptations that continue to this day.4

This Prologue engages with The Rite of Spring as a gestural event. It argues that the piece and its surrounding discourses inaugurate a cultural imaginary that explores choreographic gesture as a prime site of aesthetic, social, political, and ethical reflection. At the beginning of the twentieth century, the meaning of gesture exceeds its association with the unintentional gesticulation that accompanies speech. As a somatic reaction, but even more so as an element of self-reflective or expressive bodily performance, gesture enters thought, and becomes itself a performance of critical thinking and agency. It does so both theoretically and choreographically, in discourse and on stage, but it also acts as a relay between the discursive and the corporeal, forming the means by which a thinking body articulates itself. Dance takes on a leading function in this endeavor. Arriving after Isadora Duncan, Ruth St. Denis, Maud Allan, and others, Nijinsky is not the first one to engage with the new gesturality that takes hold of the field of movement. His choreography for The Rite of Spring, however, due to its extraordinary collaborators, the sheer scale of its production, and the exposure it received as part of the repertory of the most famous ballet company at the time, crystallizes the early twentieth-century explosion of gestural discourse and performance. In this book, Sacre is considered a primal scene of modernist gesturality: it is the moment at which the revolutionary power and conceptual reach of gesture become discernible.5

The following will investigate Sacre’s gesturality in a triangular reading, juxtaposing an analysis of the historical performance with two signature texts on the piece: Theodor W. Adorno’s chapter on Stravinsky in his 1949 Philosophie der neuen Musik (Philosophy of New Music), and Jacques Rivière’s essay on the original production, published in La Nouvelle Revue Française in November 1913.6 Both texts are also key documents of gestural theory. While Adorno develops an intensely anti-gestural argument with regard to Stravinsky’s musical aesthetic, Rivière celebrates Nijinsky’s choreography as a technique that excavates movement’s gestural core. The juxtaposition of Adorno’s and Rivière’s writings carves out a theory of gesture that defines the gestural as a form of interruption of the flows of music and movement. Choreographic gesture is associated with a punctuating and punctuated energy that will be further explored especially in the Introduction, and in chapters 2, 3, 5, and 7. In my analysis of the historical performance of Sacre, I consider punctuation as an aesthetic strategy of productive impairment that not only manifests, but also critically exposes the primitivism that is Sacre’s signature trait.

ADORNO ON STRAVINSKY: GESTURAL SHOCK

Adorno’s Philosophy of New Music is polemical throughout, yet its second part, entitled “Stravinsky and the Restoration,” constitutes an outright manifesto against the composer. This second part is devised as a counterfoil to the book’s first part, “Schoenberg and Progress,” setting up a contrast between the avant-garde modernism of Arnold Schoenberg’s twelve-tone technique and Stravinsky’s “regressive” modernism of rhythmical musical mimesis. Radical newness, which Adorno associates with Schoenberg’s venturing into fresh atonal territory, is set against Stravinsky’s return to the ostensibly archaic resource of popular musical traditions. In Adorno, Stravinsky’s restorative inclinations are not only aesthetically doubtful. They are deemed “fundamentally complicitous with the destructive tendencies of the age,” and thus fail on a political level too.7 Yet despite his preference for Schoenberg, Adorno grants neither of the two composers the ability to establish a new sense of subjectivity as the ethical instance that might be fully reflective of the twentieth century: Schoenberg falls short because his music eventually turns around itself by fetishizing its own principle of seriality, and Stravinsky because he renounces the subjective element of melody. The latter, however, remains the persona non grata of Philosophy of New Music, as Adorno berates him for siding with fascist ideology, in spite of his liberal roots (see PM, 112).

Philosophy of New Music was published around the first time that Adorno returned to Germany from American exile. His sense of historical trauma and his fear of a renewed rise of Nazism amounted to forms of personal involvement that were too acute to allow for a distanced attitude toward a composer who employed a potentially pre-fascist aesthetic. Not unlike other contemporaneous examples of cultural criticism such as Siegfried Kracauer’s From Caligari to Hitler or Lotte Eisner’s The Haunted Screen, both of which deal with cinema, Adorno’s treatise formulates a reassessment of modernist aesthetics from a post-Holocaust perspective; and it follows an impulse to dismantle ideological thinking in early twentieth-century art that is similarly passionate if less explicit than that evinced in Kracauer’s and Eisner’s texts.8 In the Stravinsky chapter, pre-fascism is traced back to Le Sacre du printemps as a piece of music that still “resounds with the uproar” (PM, 113) of World War I. In the introduction of Philosophy of New Music, this psycho-historical dimension is equally present: when Adorno talks about dissonance, his use of the concept reaches beyond the musical paradigm, denoting an existential rift that goes right across the outside world and into the listeners’ minds for whom it is “intolerable” as it speaks of their own situation (PM, 11). Dissonance, in fact, has certainly entered Adorno’s own discourse in “Stravinsky and the Restoration,” generating a tormented piece of cultural criticism,9 while his tendency to (a)

rhythmically pound in his claims seems to function like an act of subversive mimicry, exorcising that which he criticizes most in the composer. Philosophy of New Music is embedded in the author’s and Max Horkheimer’s larger project of the Dialectic of Enlightenment, which enquires into the dynamic in which progress remains haunted by that which it leaves behind, or, as Robert Hullot-Kentor puts it, where “the possibility of the new is consumed in the modern’s reproduction of itself as the recurrently primitive.”10 Adorno’s aesthetic theory is based on the conviction that both highbrow and lowbrow art reveal a culture’s political self-understanding. In his 1950 response to criticism of Philosophy of New Music, entitled “Misunderstandings,” Adorno is very clear about his preoccupation with an “objective spirit” that asserts itself in art, but does so “over and above the heads of individual artists as well as beyond the merits of individual works” (PM, 165). Apart from Kracauer’s 1927 essay on the “Mass Ornament,” which famously discusses the kick-lines of the Tiller girls as corresponding to the conveyor belts of rationalized mass production, early twentieth-century sociopolitical critique of a comparable quality does not include dance within its range of subjects. Dance writing of the same period, in turn, does not develop an equally acute socio-political and psychoanalytical critique.11 Adorno’s scattered remarks about ballet music and dancerly gesture in “Stravinsky and the Restoration” are valuable, then, but they are also reductive, associating gesture with an unthinking, somatic kind of reflex, set in the vicinity of what Martin Puchner summarizes as modernist gesture’s propensity toward “ritual, archaism, fascism, and uncritical violence.” Puchner argues that this regressive context “remains an implied danger, from Wagner on,” and that it stimulates an important critical debate on the politics of gesture.12 But Adorno’s reading also excludes a more balanced view of the complex and heterogeneous field of embodied modernist gesturality. As David Levin shows, Adorno dismisses a closer analysis of Sacre as a work for the stage because of a surprisingly undialectical understanding of the performative dimension of music, which stands in sharp contrast to his sophisticated analysis of musical scores.13

Adorno, who was ten years old in 1913, never attended any of the few performances of the original version of Sacre, and does not seem to have been interested in finding out about Nijinsky’s choreography in retrospect. If gesture gains prominence in his thinking on literature, opera, and film, as well as “a central category for modern music,” it is an intra-musical rather than a theatrical element.14 But while he neglects the theatrical nature of Sacre as a work for the stage, Adorno infuses his musical analysis with performative associations. These associations are instrumental for his reading of the place of the subject, and of subjectivity, in Stravinsky’s score. In Philosophy, Adorno declares from the outset that he treats “the antipsychological Stravinsky” dialectically, from

the perspective of the “damaged subject on which his œuvre is patterned” (PM, 4). Damage is represented musically by replacing the agency of the autonomous individual with forms of merely instinctual defense. Gesture, here, is prone to the de-individualizing drive of the score’s irregular rhythmical structure, which asks for immediate physical responses; it is associated with a form of “shock” that makes “the individual directly aware of his nullity in the face of the titanic machinery of the entire system” (PM, 117). Gesture is reactive rather than active; more than anything else, it is a physical reflex of (failed) protection against harm.15

Adorno’s aesthetic of gesture thus rehearses the theory of psychic trauma that Freud developed in Beyond the Pleasure Principle. In Freud, trauma is induced by an element of surprise in the fright experienced by the victim, “the state that possesses us when we find ourselves plunged into danger without being prepared for it.”16 In Adorno, this happens to Sacre’s girl victim, the Chosen One. She is at the mercy of Stravinsky’s polyrhythm, unable to foresee or assimilate the music’s arbitrary blows:

This is manifest in the “Danse finale de l’élue,” in the human sacrifice, where the most complicated measures alternate with each other in the smallest temporal segments. This compels the conductor to walk a tightrope for the sole purpose of using convulsive blows and shocks that cannot be anticipated by any preparatory anxiety to hammer into the dancer and the audience an immutable rigidity. [. . .] it is accepted that the shock cannot be integrated into the self. The musical subject abdicates the struggle to bear up and instead makes do by acceding to the blows in its own reflexes. He [sic!] acts literally like someone gravely wounded, the victim of an accident that he cannot absorb and that he therefore repeats in the hopeless exertions of dreams. What appears to be the complete absorption of the shock, the compliance of the music with the rhythmical blows inflicted on it externally, is in truth precisely the sign that the absorption has miscarried. (PM, 117–18)

The gestural body that emerges as a result of such music is defined by repetitive reactions. In this, as Adorno has it, Stravinsky’s score is representative of all traditional ballet music, which “prescribe[s] gestures, and, beyond that, comportments” (PM, 126); what is more, Stravinsky even “reestablished” the “disciplinary nature of dance [. . .]. His accents amount to so many acoustic signals to the stage” (PM, 143). Adorno’s musically defined gesture does not partake in the “expressive-dynamic” (PM, 145) paradigm of the psychological tradition, nor in any other lost model of individuation. But neither does it belong to the progressive forms of Schoenbergian constructivist modernism.17 Gesture is at the service of ritual violence, becoming “a name for everything

that is regressive, primitivist, and therefore non-modernist,” as Puchner writes, referring to Adorno’s narrow definition of modernism as exclusively avant-garde.18

Adorno links the condition of his gestural subject to the “disproportion in late industrialism between the body of the individual and the things and forces of technical civilization” (PM, 117). In Minima Moralia, this disproportional relationship between technology and the human prognosticates fascism: “The movements machines demand of their users already have the violent, hardhitting, unresting jerkiness of Fascist maltreatment.”19 In Adorno’s account of Sacre, the rhythm of archaic ritual thus meets that of machinic pulse, resulting in a musical style that he characterizes as “motor function”: “even and persistent stomping.”20 Now shifting attention from irregular to regular beats, this style builds up toward a surge to merge and comply, as becomes obvious in the passage entitled “Identification with the Collective”:

[. . .] there is no aesthetic antithesis between the one sacrificed and the tribe; rather, her dance accomplishes the uncontested, immediate identification with it. [. . .] The girl chosen dances herself to death [. . .]. Nothing of her as an individual is reflected except the unconscious and accidental reflex of pain: In terms of its inner organization, her solo, like all the other dances, is a collective circle dance bereft of any dialectic of universal and particular. (PM, 118–19)

The totalitarian ideology of Sacre consists, then, in a logic of non-distinction between individual and collective that culminates in the fact that the girl victim chooses her own destruction in accordance with the choice of the group. It is also at work in the music’s alliance with its own archaisms, inciting the public’s “sadomasochistic” enjoyment of the “subjectless condition” that is performed in the score: “If the viewer does not simply enjoy the liquidation of the young girl, he empathizes with the collective and, himself its potential victim, thereby imagines participating in the collective force in magical regression” (PM, 119). In Adorno’s reading, the result of this “is certainly not the identification of the public with the psychic agitation allegedly expressed in the dance; rather, it is an electrification equal to what seizes the dancers” (PM, 144).

In the dedication of Minima Moralia, Adorno links the destruction of the subject that results from such a setting explicitly to the Holocaust: “the nullity demonstrated to subjects by the concentration camp is already overtaking the form of subjectivity itself”;21 in Philosophy, he writes in a prognostic mode:

In Stravinsky, subjectivity takes on the character of sacrifice, but—and in this he mocks the tradition of humanistic art—the music identifies not with

the victim but with the annihilating authority. Through the liquidation of the victim, it rids itself of intentions, those of its own proper subjectivity. (PM, 109–10)

Adorno observes this loss not only in the prominence of rhythm as blow, but also in the absence of melody.22 Melodious musical subjectivity is replaced with the detached attitude of pastiche, of “musical quotation, self-reproduction, willful fragmentation, imitation of ancient forms,” which together produce “the prehistorical” as artistic “effect” rather than authentic reconstruction.23 This strand of Adorno’s argument jars with the otherwise unrelentingly accusatory tone of the Stravinsky chapter. It detects a salutary “dialectical ambiguity” (PM, 112) in the works of the composer through which he is in fact partly redeemed. In anticipation perhaps to objections against his diatribe, Adorno here acknowledges a type of thoroughly self-aware musical bravura in Stravinsky. This bravura may take pleasure in the archaism that it produces, but does not actually believe in it: “all regression in Stravinsky’s work is manipulated precisely as a copy that never for a moment forgets aesthetic self-control.” In other words, if regression in this context equals violence, “The Rite of Spring wants not simply to surrender itself” to the violent impact “but to gain mastery over it through copying it” (PM, 113). In “Misunderstandings,” Adorno argues that those among Stravinsky’s works that dedicate themselves “most shrewdly to such mimesis are the most productive ones” (PM, 167). Accordingly, in the Stravinsky chapter we encounter passages where Adorno presents the “detachment” (PM, 111) of Sacre’s staged disclosure of barbarism as “mimetic defense” (PM, 126) against the actual madness of war, rather than as war’s unthinking propagation. The more positive passages even associate Sacre with the liberal spirit of bourgeois revolution. Fascism, Adorno claims, “which literally liquidates liberal culture along with its critics,” is “just for this reason unable to tolerate” in its theaters such disclosure of barbarism as spectacle:

In the Third Reich of countless human sacrifice, The Rite of Spring would not have been performable, and whoever dared directly to acknowledge the barbarism of the ideology’s modus operandi was dropped and disgraced. Without its lies, German barbarism—as may indeed have occurred to Nietzsche—might well have exterminated barbarism itself along with the lies. (PM, 112)

At the same time, however, an aesthetically advanced strategy that distances itself from that which it pronounces is ultimately considered utterly cynical, given the subject matter of the piece (PM, 132). The argument turns around again: in addition to demonstrating how detachment is out of place in the face

of violent death, Adorno also shows how this strategy does not hold in the first place. Carried away by its perfect construction of archaic essentialism, the music buys into its own simulacrum. Fending off the drastic brutality of regression by exposing it does not mean that this brutality is redeemed. The music’s production of archaic effect, that is, works, in the end, only too well. Even if brutal “nature” is only a phantasm in Rite of Spring, this phantasm ultimately proves to be the “herald of absolute oppression” (PM, 113). Stravinsky’s “already-lapsed modernism” thus implies “an opening” toward the tyranny of “the primordial past” (PM, 111). Self-reflective play as a form of distanced subjectivity becomes complicit with the sacrifice of the subject; antipsychological strategy dissolves into diffuse communality. Adorno uncovers a troubling tendency toward positivistic essentialism both in Sacre and in other works by the composer.24 Superseding anydetachment, “aesthetic nerves” ultimately “quiver to return to the Stone Age” (PM, 113):

[. . .] with this virtually historicizing evocation of a primordial age, at heart held playfully distant, [. . .] Stravinsky was soon unable to satisfy his urge for objectivism. He settles the tension between the archaic and the modern in such a way that for the sake of the authenticity of the archaic, he jettisons the primeval world as a principle of stylization. (PM, 120)

If Philosophy of New Music is at once disheartening and intellectually engaging, it is so because both its discourse and its content are driven by the presence of a post-Holocaust subject that is irrevocably “damaged.” The poly-rhythmical elements of music and plot resonate in the dissonant tracks of Adorno’s argument in “Stravinsky and the Restoration” and its side texts. Within Adorno’s reading of Stravinsky’s “antipsychological” (PM, 4) modernist aesthetic, the twentieth-century subject finds its most prescient and concise expression in the automatic shock reactions of gestural trauma: gesture, in Adorno’s Sacre, is a somatic reflex of defense or submission rather than intentional action or expression. In Nijinsky’s choreography, Adorno’s damaged subject acquires a more multifaceted gestural register; and it is this register that Rivière traces in his response to the staged dimension of Rite of Spring.

RIVIÈRE ON NIJINSKY: NEW GESTURAL EXPRESSION

Rivière’s essay titled “Le Sacre du printemps” of November 1913 is the second installment of a review whose first, shorter version had already appeared in August that year . Rivière thus waited some time before fully responding to a spectacular performance, perhaps because he developed in the longer essay next to his clear-sighted observations on dance a specific, anti-symbolist

literary agenda, whose conservatism stands in a curiously jarring relationship with the author’s appreciation of a movement aesthetic that was radically avantgarde.25 Yet even if the gap between the performance in spring and the account in autumn indicates a number of months during which impressions must have worked within the author’s mind, the result still shows the impact of spontaneous reaction. Its recollection of detail is remarkably precise. In contrast to Adorno’s exclusive focus on the musical score, Rivière offers us an eyewitness account of the performance, at the center of which is this performance’s innovative gesturality.

Clarity of image and recollection, however, are not only proof of Rivière’s acute observational skills. He detects this clarity in the choreographic work itself, and considers it one of its great merits. It is a spirit of aesthetic enlightenment that he finds in the movement language of the Ballets Russes, and in Nijinsky’s choreography in particular. In contrast to Sacre’s unenlightened content, its choreographic form betrays utmost novelty; it gives the body over to the sense of sight. What emerges is a non-normative language of gesture—a gestural coming out, as it were—that allowed dance to arise from “the shadow, [. . .] let all [its] gestures be seen, write them all out without mystery, and nevertheless be deep and pathetic” (SP, 134).26 Far more than Stravinsky’s music, which he discusses at the beginning of the essay, Rivière considers the choreography to be a radical contribution to post-symbolist aesthetics, one to which the public needs to be “acclimatiz[ed].” Rivière’s impetus—unlike Adorno’s—is not to dismantle ideological charge, but simply to “define” this “novelty a little more precisely” (SP, 133). On Nijinsky’s dancing during the first Paris evenings of the Ballets Russes, pre-Sacre, he writes:

At each whirl of Nijinsky, when he knelt, crossed his hands, and closed the figure he had begun when he leaped into space, my whole pleasure was to see again in thought the entire sweep of his movement—alive, pure, severe, rising up as if one blow had torn it away from the vague mass of the possible in a single piece. No doubt, no smudges, nothing appealing to my hesitation; I was strong and content like a man who, in a glance, sees a system of propositions scrupulously isolated from error in all its points. (SP, 134)

Yet even though the combination of a new choreographic and performative style with outstanding dancerly skill brings about revelation, it still disguises a body that Rivière desires to see “without sauce” (SP, 125). What prevents him from doing so is too much movement, especially the elegant, flowing, flying type of Mikhail Fokine’s choreography, for instance in Le Spectre de la rose, where “the body of Nijinsky literally disappears in its own dance” (SP, 135–36).27 Dance’s