Fungipedia

A Brief Compendium of Mushroom Lore

Lawrence Millman

Illustrations by Amy Jean Porter

Copyright © 2019 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press

41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TR press.princeton.edu

Epigraph excerpt from “The Ridge Farm” in The Complete Poems of A. R. Ammons: Volume 2, 1978–2005, edited by Robert M. West, published by W.W. Norton & Company, 2017.

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Control Number: 2019935892

ISBN 978-0-691-19472-1

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

Editorial: Robert Kirk and Kristin Zodrow

Production Editorial: Mark Bellis

Text and Cover Design: Chris Ferrante

Production: Steve Sears

Publicity: Sara Henning-Stout and Julia Hall

Copyeditor: Laurel Anderton

Cover, endpaper, and text illustrations by Amy Jean Porter

This book has been composed in Plantin, Futura, and Windsor

Printed on acid-free paper. ∞

This book is dedicated to all fungi, even the toxic ones, in honor of their ability to astonish, amuse, & often humble me.

The world depends on fungi, because they are major players in the cycling of materials around the world.

e . o . Wilson

Attend to mushrooms and all other things will answer up.

A.

r . Ammons

There is something absolutely fascinating to me about being present at the exact moment when a mushroom is mushrooming.

John cA ge

Mycology beats urology any day.

Bryce Kendric K

Preface

“The humblest fungus displays a life akin to our own,” wrote Henry David Thoreau in his Journal in 1858. This observation shows Thoreau’s usual prescience, since recent phylogenetic analyses of DNA have determined that fungi occupy a branch on the tree of life surprisingly close to our own branch. The same analyses also indicate that the reader of this Fungipedia and the chanterelles he or she is getting ready to cook have the same distant ancestor, probably an organism not unlike a present-day marine choanoflagellate.

But our similarity with the inhabitants of Kingdom Fungi is not simply genetic. Neither fungi nor we possess the green pigment known as chlorophyll, so we can’t make sugars from sunlight or CO2, and thus we’re obliged to obtain our food from living or dead organic matter, animal or vegetable. Both of us have evolved special enzymes that allow us to digest this matter, although we tend to grab and then engulf it, while fungi turn it into liquid form.

Speaking of food, certain fungi can be extremely picky (like some of us) about their dietary needs: one species (Herpomyces stylopage) dines only on the hairs of cockroach antennae; another (Cephalosporium lamellaecola) eats only the tips of stalactites in caves; trichomycete species live in the hind guts of aquatic arthropods such as mosquito larvae; and a newly discovered species (Aliciphila vulgaris) can be found only on leaf litter moistened by elk urine. Such substrates might actually seem quite pleasant compared to those at the ruined Chernobyl nuclear power plant in the Ukraine, where various fungal species are currently dining on leftover radiation.

Given the similarities between fungi and our species, it’s not surprising that we relate to fungi differently from the way we relate to plants. They inspire in us phobic reactions, total delight, anthropomorphic thoughts (in Russian, an old person is called a staryy grib a dried-up mushroom), fictional monsters, postage stamps, disgust (the Greek physician Nicander called fungi “the evil ferment of the earth”), and—as in the case of the Mazatec curandera Maria Sabina, who called magic mushrooms “children of God”—deification. They also inspire animation: Walt Disney provided the fly agaric (Amanita muscaria ) with a role in the dancing mushroom sequence in Fantasia, but he didn’t give even a minor part in the film to a sashaying phragmites or a sedge.

How fungi arrived in our world has also been a prod to the human imagination. In Lithuania, fungi were once considered the fingers of Velnias, the one-eyed Baltic god of the dead, reaching up from the underworld to feed the poor. In parts of India, Bangladesh,

and East Asia, they are still thought to originate from a urinating dog. Far more common is the belief that they came from the world above us rather than the terrestrial or subterrestrial world. The ancient Greeks thought they were the product of seeds placed on lightning bolts by Zeus; an old Persian legend attributes them to a sky goddess shaking the lice from her trousers; and the contemporary Inuit in the central Canadian Arctic believe mushrooms are the anaq (shit) of shooting stars, since they often appear on the tundra the morning after a shooting star leaves a trail of detritus across the night sky. I doubt that anyone has ever proposed that a chrysanthemum or daffodil was excreted into their garden by a shooting star.

In the previous paragraphs, I’ve used the word “mushroom.” That word usually refers to a fungus with an umbrella-shaped fruiting body as well as pores or gills beneath a cap. Examples include the king bolete (Boletus edulis), so-called buttons (Agaricus bisporus), and the beautiful but deadly destroying angel (Amanita bisporigera). Yeasts aren’t mushrooms, but they are fungi. Likewise, rusts, polypores, mildews, puffballs, bread mold, and dead man’s fingers—all members of Kingdom Fungi—aren’t mushrooms, either. Such distinctions don’t really matter, unless a person is writing a scholarly paper, in which case he or she would never refer to a dead man’s finger (Xylaria sp.) as a mushroom. In this not necessarily scholarly Fungipedia, I’ll be using the two words more or less interchangeably. Whenever possible, I’ll also be using common names such as dead man’s fingers and destroying angel rather than Latin binomials.

Other words I’ll be using with a certain abandon are possibly, probably, perhaps, maybe, usually, typically, and sometimes, or their equivalents. For mycology (from Greek mykos, “fungus,” and logon, “discourse”) is a relatively young pursuit, and many aspects of it have not been fully or even cursorily investigated. Also, virtually every known mycological rule has exceptions. For example, a wood- inhabiting fungus that’s supposed to grow on conifer logs might occasionally take up residence on deciduous logs, and vice versa. Perhaps the mycelium has made a mistake. Perhaps stressful weather conditions have made it choose any proverbial port in a storm. Perhaps the fungus just wants to be different. Or maybe it wants to confuse or even humble us humans. Anyone who has devoted long hours to trying to identify a fungal specimen can appreciate that last example of anthropomorphic thought!

By now the reader has probably finished cooking the chanterelles and might be wondering whether to put them in an omelet, serve them with a steak, or dunk them in a bean soup. To learn the answer to this question, consult James Beard or Julia Child, but you needn’t bother leafing through this Fungipedia, because it’s not a cookbook. Rather, it’s a compendium of ecological, scientific, ethnographic, and occasionally just plain weird fungal lore. It also includes biographical information about mycologists, such as, for instance, the fact that bolete expert Walter “Wally” Snell was once a catcher for the Boston Red Sox.

Here I should confess that I regard edibility as (prejudice alert!) perhaps the least interesting aspect of any fungus. So I won’t be discussing the edibility of

most fungi, unless the species happens to be corn smut (Ustilago maydis), a traditional food eaten by the Aztecs. Or unless the diner happens to be a mite, a beetle, or even an amoeba, certain species of which depend on fungi for their survival. Or unless that diner is another fungus cheerfully engaging in cannibalism. An example of a fungal cannibal is the parasite Hypomyces lactifluorum attacking a Russula or a Lactarius and transforming it into a lobster mushroom.

Just as we like to eat fungi, certain fungi like to eat us, or at least parts of us; they’re found in our oral cavities, on our skin, in our lungs and vaginal tracts, and on our nails. Two hundred sixty-seven different species have been documented in our guts, where they probably help metabolize sugars. Occasionally, fungi even grow on our brains. I once attended an autopsy performed by a pathologist friend, and I saw a large mycelial mass embracing the fibers that connected the two cerebral hemispheres of the cadaver’s brain. Remarkable! I thought.

The fungus in question (probably Aspergillus fumigatus) might be called a pathogen, but the brain belonged to a much-ravaged street person who, in addition to his other afflictions, had probably been a victim of AIDS. Healthy individuals possess cells called macrophages and neutrophils designed to fight off fungal infections, but not this fellow. His compromised immune system offered a welcome mat for the fungus. Indeed, a large number of otherwise mild-mannered fungi can wreak havoc on an extremely immunocompromised individual. And not only humans: numerous fungi, mild mannered or otherwise, can wreak similar havoc on other

organisms with compromised immune systems, an activity I’ll mention in several entries in this Fungipedia. Of course, there are significant differences between fungi and us. Not only have fungi managed to survive without availing themselves of supermarkets, mechanical transport, health care facilities, computer-type devices, or day care centers for their young, but they’re also (unlike a large percentage of us) excellent ecologists. Consider trees that have been hammered by a woodpecker, struck by lightning, sideswiped by a car, or that are simply very old. You could say that such trees have compromised immune systems themselves. Were it not for the recycling abilities of fungi, they’d be perpetually standing corpses, and the soil wouldn’t get the nutrients on which most plants depend. Eventually, there would be very few plants, as well as virtually none of the organisms that depend on plants for their own nutrients. Our planet would end up even more beleaguered than it already is.

Now let’s look at healthy trees and other plants. Between 90 and 95 percent of them have fungi as their significant others, for they have nutrients- for- carbs relationships via their roots with those fungi. Indeed, it’s possible that plants developed roots not long after they became terrestrial in order to connect with fungi. If plants could speak, they might say to their fungal partners, “I’ll give you carbohydrates if you give me nitrogen and phosphates as well as help me with water uptake.” To which the fungus might reply, “My pleasure, mate.” Actually, plants and fungi can speak to each other or at least communicate with each other via diffusible molecules, by which either one can express a need to

the other for nutrients. Such relationships are known as mycorrhizal, from the Greek words mykos (fungus) and rhiza (root). An ectomycorrhizal relationship is one in which the fungus forms sheaths around a plant’s roots, while an endomycorrhizal relationship is one in which the fungus penetrates the cells of those roots. Without one or the other of these partnerships, trees and other plants would be at best scrawny versions of their partnered selves. Here I might add that mycorrhizal fungi also sequester vast amounts of carbon in the forest floor, thus preventing that carbon from escaping into the already too carbonated atmosphere.

In any relationship, one partner can make the other miserable. So it is with parasitic fungi and their hosts. Think of the numerous Ophiocordyceps species that attack insects or their overwintering larvae. Think of Dutch elm disease ( Ophiostoma sp.), chestnut blight (Cryphonectria parasitica), ash dieback disease (Hymenoscyphus fraxineus), and beech bark disease (Neonectria sp.). Think of honey mushrooms (Armillaria sp.) obstructing the flow of nutrients from a tree’s roots to its trunk. Even think of the Cladosporium species that degrade stained-glass windows.

It’s too bad that none of the hosts can take out a restraining order against such disagreeable partners. But if the fungus were gifted with words rather than diffusible molecules, it might respond to the putative complaints of its host by saying, “Hey, we parasites gotta live, too.” The more philosophical of them might add, “Life comes from dying.”

Wood-inhabiting fungal parasites create homes for cavity-nesting birds such as chickadees and warblers;

they also create niches for specialist invertebrates such as beetles, spiders, and annelids. Since they usually infect older trees, wood- inhabiting fungi open the forest canopy for younger trees, and once that canopy is open, ground plants take over space that might once have been denied them. “Thanks, friends, for serving as agents of habitat restoration,” both these trees and other plants might remark to the fungal parasites in question if they themselves could talk.

As the union of at least one fungus and an alga or a cyanobacterium (a type of bacteria that obtains its energy from photosynthesis), lichens represent a different type of parasitic relationship, one in which the fungus keeps its partner as a slave. More whimsically, that partner has been described as “a damsel in distress.” Although lichens happen to be members in good standing of Kingdom Fungi, no less than an oyster mushroom or a destroying angel, mycologists and lichenologists are often either ignorant about or indifferent to each other’s disciplines. Indeed, my own knowledge of lichens is relatively limited, so I’ve included only a tidbit of information about them in this Fungipedia . In my defense, I should say that other books about fungi, guidebooks or otherwise, don’t usually include a lot of information about lichens, either. Perhaps one of these days a lichenologist will cobble together a Lichenopedia?

Maybe the reader of this book hasn’t been cooking chanterelles at all. Instead, maybe that reader has been making a tea from chaga or reishi to cure gout or hemorrhoids, or at least stimulate his or her immune system. Or maybe he or she is taking turkey tail or cordyceps supplements in capsule form for the same purpose. For

fungal medicinals have become a global rage. “Is it medicinal?” is rapidly replacing “Is it edible?” as the most popular question asked of mycologists.

I’ll investigate this last subject in the following pages, but for now let me mention my own favorite fungal medicinal—a walk in the woods in search of fungi. The experience of such an extraordinary variety of shapes (tongues! ears! erect phalluses! corals! teeth! birds’ nests! orange peels!) cannot help but make a person feel, if not healthier, at least more buoyant. And since fewer than 5 percent of all fungi species have been described, there’s always the chance of finding a species new to science. But even if you find only a species old to science, you might still have the same reaction to it as composer-mycologist John Cage did when he found a perfectly ordinary mushroom and exclaimed (in his diary M): “Supreme good fortune—we’re both alive!”

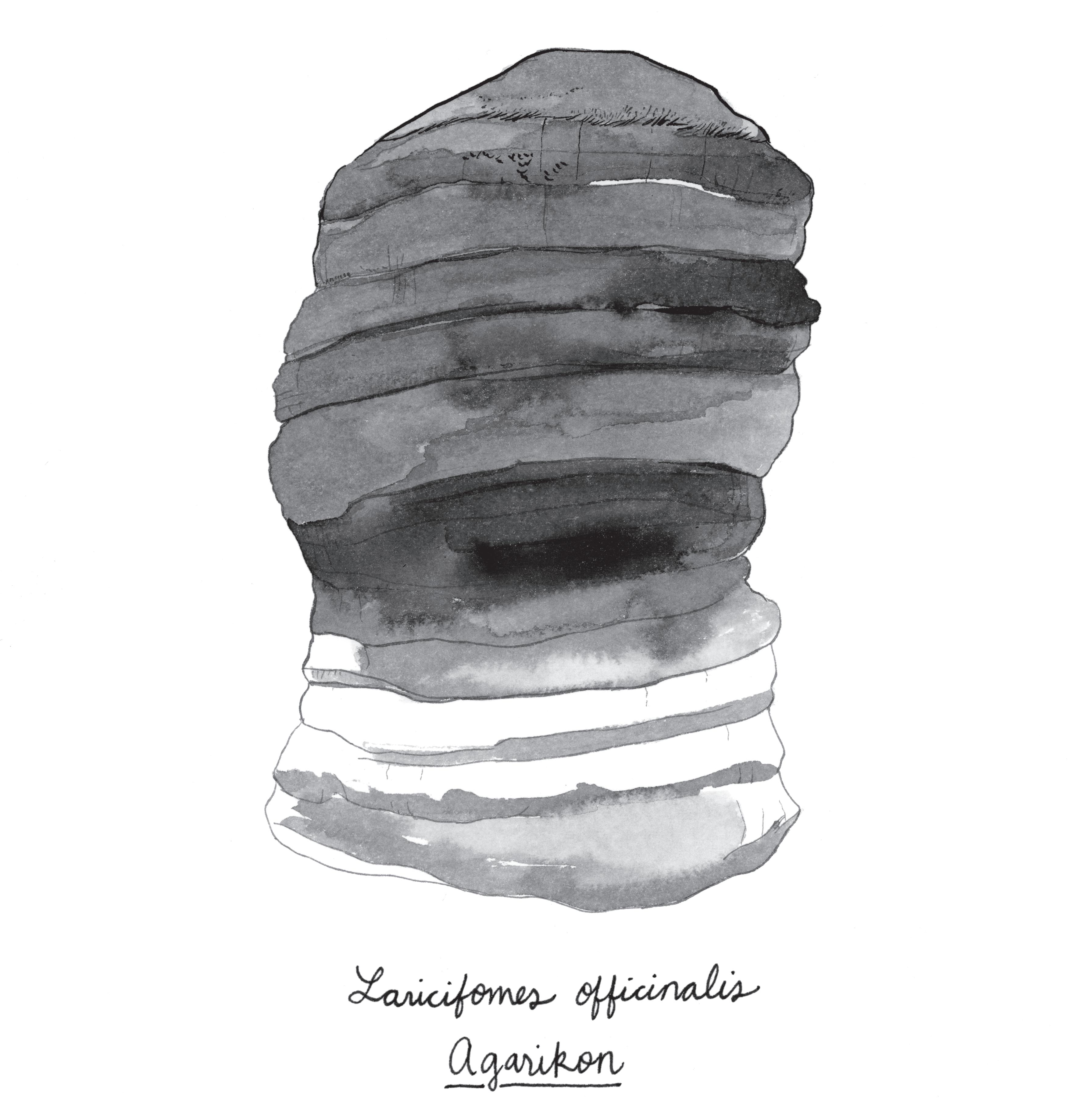

Agarikon (Laricifomes officinalis)

Both the ancient Scythian name and the current name for a large, pendulous polypore with a grayish, zoned cap. In western North America, agarikon’s host trees are old-growth conifers, primarily larch. Although rare in eastern North America, it’s common in Europe.

Probably because they contain a fatty acid called agaric acid, agarikons have long been a high-ranking fungal medicinal, about which the English herbalist John Gerard (ca. 1545–1612) wrote: “It provoketh the urine and bringeth down the menses . . . and purgeth stools.” It was formerly called the quinine conk because a decoction from it was once used to bring down the

fever of malaria. Specimens were occasionally sent down to the tropics from western North America to relieve the pain of scorpion stings.

West Coast native people placed carved agarikon specimens on the graves of their shamans. In British Columbia, the Haida First Nation people personified the polypore as a deity called Fungus Man. According to the legend, Raven created men but did not know what to do next, so his friend Fungus Man took him to the island that was inhabited by female genitalia. Raven fastened some of the genitalia onto the men, and lo! those men became women. Thus humankind owes its existence to Fungus Man . . . or so the legend tells us.

See also Ethnomycology; Polypores.

Aksakov, Sergei (1791–1859)

Russian landowner and naturalist, about whose memoir A Family Chronicle his fellow author Nikolai Gogol wrote: “None of our Russian writers can depict nature with such strong and fresh colors.”

At the end of his life, Aksakov started writing a book titled Remarks and Observations of a Mushroom Hunter. This uncompleted work contains the following rumination: “I believe the key to the mystery of mushroom birth lies in the roots [of trees]. . . . When they die, the mushrooms cease. . . . The complete dependence of mushrooms on the roots of trees is shown by the fact that certain trees only produce their own kinds of mushrooms.”

From these words, it would appear that Aksakov recognized both the existence and the significance of mycorrhizal relationships between fungi and trees well

before actual mycologists discovered such relationships. In fact, the word “mycorrhiza” wasn’t coined until 1885, by the German scientist Albert Frank.

Aksakov coined the phrase “quiet hunting,” now commonly used in Russia to describe foraging for mushrooms. The phrase refers not only to the absence of rifle fire when a person is hunting mushrooms, but also to the tendency of mushroom hunters not to divulge the whereabouts of their collection sites, lest those sites be ravaged by someone else.

See also Ectomycorrhizal Fungi.

Alder

Tongue (Taphrina robinsoniana)

Not to be confused with the plant in the lily family called an adder’s tongue, alder tongues are often called mycocecidia, a word that means they create galls or gall-like structures in their plant hosts.

The species in question is an ascomycete that creates a tonguelike swelling on the catkins of several North American alder species. Initially, these swellings appear as green lumps and then become brownish as they mature. At last they harden and become black, at which point they turn their host into a collection of tongues. Catkins end up looking so distorted that they seem to be in considerable pain. Typically, however, alder tongues don’t cause serious harm to their host. The distorted structures consist mostly of plant tissue forced to proliferate by the fungus so it can spread its spores.

Another Taphrina species, T. deformans, causes the disease known as leaf peach curl, which sometimes causes premature defoliation of leaves, but sometimes

doesn’t. Whether it succeeds usually depends on (like so much in Kingdom Fungi) environmental conditions. There are approximately 30 species of Taphrina , all of which are dimorphic—they spend half their life cycle as innocuous yeasts and the other half as plant parasites.

See also Ascomycetes; Prototaxites.

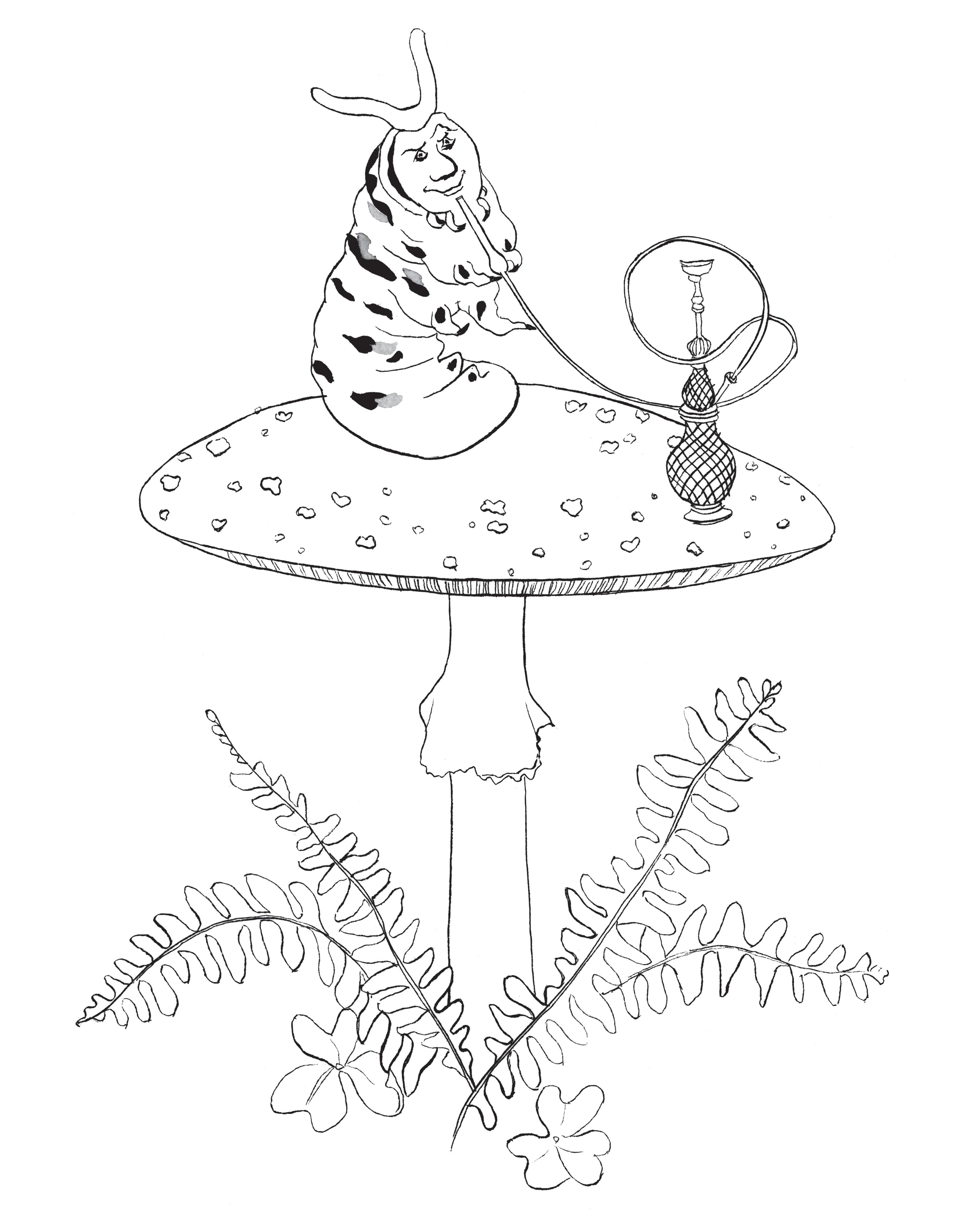

Alice in Wonderland

Delightfully surreal 1865 novel by the Reverend Charles Dodgson, otherwise known as Lewis Carroll, which features perhaps the most famous mushroom in all of literature. On top of that mushroom is seated an almost equally famous hookah-smoking caterpillar. “One side [of the mushroom] will make you grow taller, and the other side will make you grow smaller,” the caterpillar observes to the heroine, Alice, who, being of an adventurous nature, decides to test this seemingly peculiar remark. It turns out to be correct.

It’s likely that Carroll learned about the mushroom in question, probably the fly agaric ( Amanita muscaria), from reading English mycologist Mordecai Cubitt Cooke’s 1860 book The Seven Sisters of Sleep . This book describes the effects of eating the fly agaric as follows: “Erroneous impressions of size and distance are common occurrences . . . a straw lying on the road becomes a formidable obstacle to overcome.” It should be noted that the first illustrator for Carroll’s own book, John Tenniel, depicted not a fly agaric but a generic mushroom. Carroll’s own illustration for Alice’s Adventures Under Ground looks like a generic mushroom, too.

Alice evolved to become a popular countercultural figure in the 1960s. For example, Grace Slick’s song “White Rabbit” includes these well-known lines: “You’ve had some kind of mushroom, and your mind is moving slow / Go ask Alice, I think she’ll know.” Grace herself certainly knew.

See also Cooke, Mordecai Cubitt; Fly Agaric.

John

Allegro, John (1923–1988)

English expert in the Dead Sea Scrolls as well as ancient Semitic languages whose decidedly offbeat 1970 book The Sacred Mushroom and the Cross proposes that Christianity was originally a deviant shamanic cult devoted to psychedelic mushrooms. The book also suggests that the word “Jesus” was actually a code name for the fly agaric (Amanita muscaria), and that Jesus himself probably never existed.

“The stories in the New Testament are a literary device to spread the rites and rules of mushroom worship to the faithful,” Allegro wrote. Indeed, he argued that the New Testament was actually a codex for a mushroom cult. Since that cult was being persecuted, its lore had to be camouflaged.

Not surprisingly, Allegro’s reputation took a sudden nosedive after The Sacred Mushroom and the Cross was published, from which it never recovered. Here I should say his scholarly reputation. There are still a few contrarian types who have a high regard for him.

See also Fly Agaric.

Another name for the tinder polypore ( Fomes fomentarius). Specimens are ash gray with concentric ridges, and they fruit on deciduous stumps and logs. Their hoof- like shape gives them another common name, hoof polypore.

The word “amadou” is probably derived from the Old French word amator, which means “lover.” Just as lovers are quick to catch fire, so too is this polypore, which was of primary importance before the invention

Amadou

of matches and other fire-making devices. Specimens were dried, pounded into fibers, and then sometimes mixed with saltpeter (potassium nitrate). Usually housed in a tinderbox, the flammable result was used as a fire starter, a kindler of one’s tobacco, or—by dentists in former times—an aid in drying teeth. In eastern Europe, hats and various items of apparel are still made out of amadou.

Since tinder polypores have been found at Mesolithic campsites dating back to around 8000 Bce , the species might have been the earliest nonedible fungus used by humankind. The Tyrolean Iceman Ötzi had a specimen, or at least hyphae from a specimen, on his much-desiccated person. A smoldering specimen is still used by the Dena’ina in Alaska and the Cree in Quebec, among other native groups, as an insect smudge. Like cigar smoke, the smoldering keeps away insects.

See also Ethnomycology; Ötzi; Polypores.

Amateur

Also called a mycophile. An individual who takes delight in fungi but doesn’t engage in applied or university science. Formerly, “amateur” was a somewhat derogatory term that suggested ignorance, but it tends not to have such a negative connotation nowadays. “Citizen scientist” is a phrase that’s now increasingly replacing the word “amateur.”

Whatever you decide to call such individuals, their interest in fungi is not associated with power, prestige, the occupational pressure to publish, or an NSF grant—they just want to learn with a capital L. Yes, they

may engage in rants on Facebook or argue incessantly about whether a species is a Mycena or a Marasmius at meetings of their mushroom clubs, but their ability to identify fungi often surpasses that of professionals. Increasingly, many of those professionals are so devoted to DNA sequencing that their only knowledge of actual mushrooms is (in the words of mycologist Andrus Voitk) “as a side order item in a burger joint.”

Amateurs and professionals are currently combining their talents with the North American Mycoflora Project, the goal of which is to identify and map the distribution and seasonality of macrofungi in North America and put the results online. This project is admirable, but it should probably have a different name, since fungi are not even remotely “flora.”

Amatoxins

Also called amanitins. A group of highly toxic, bicyclic peptides not only in Amanita species like the death cap (A. phalloides) and the destroying angel (A. bisporigera), but also in a trio of “deadlies”— the deadly galerina ( Galerina marginata ), the deadly lepiota ( Lepiota josserandii), and the deadly conocybe (Conocybe filaris). These compounds inhibit the enzymes necessary for the production of RNA, which means cells are unable to synthesize new proteins, so they grind to a halt. Amatoxins accumulate especially in the liver, more or less causing that organ to digest itself.

Possible treatments include a liver transplant, hemodialysis in the case of kidney failure, and decontamination of the digestive tract with charcoal—but not, definitely not, eating raw rabbit brains, an early “cure”

based on the apparent ability of rabbits to eat toxic mushrooms with impunity.

Amatoxins weren’t designed to kill members of our species. Rather, they’re probably biochemical waste, transported by the mycelium to the fruiting body. An example of a similar transport is caffeine in a coffee bean.

Many Amanita species don’t have amatoxins, but those that do have given a bad reputation to the others.

Species such as Caesar’s amanita (A. caesarea) and the blusher (A. rubescens) are in fact edible . . . with caution.

See also Death Cap; Poisonings.

Ambrosia

A Greek word meaning “food of the gods.” In this case, the “gods” are scolytid (a.k.a. ambrosia) beetles, and their food happens to be a fungus, usually an asexual