ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This book has been with me for a long time and through a lot of changes. There are tons of people to thank, personally and professionally.

I gratefully acknowledge the financial support that underwrote major parts of the research and writing of this book. The McLaughlin Grant from the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, University of Florida, was absolutely critical in providing a summer of intensive research in Nashville. A Dissertation Writing Fellowship from the Louisville Institute was similarly significant in allowing concentrated energy and attention to completing the first draft. Smaller but valuable grants from the Southern Baptist Library and Archives, Emory University, and Georgia State University, plus the John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson presidential libraries, permitted me to explore important research angles. The Center for Africanamerican Urban Studies and the Economy (cause) at Carnegie Mellon University generously supported my ongoing research agenda, as has Newcastle University. I also thank folks at Edinburgh, Sunderland, and Cambridge Universities for chances to present my work and talk through my findings. Similarly, I’m grateful to the staff and fellows at Harvard University’s W. E. B. Du Bois Institute, sponsor of the National Endowment for the Humanities’ Summer Institute on civil rights, for a month of intensive thinking and study. All created tremendous opportunities for me.

I would also like to acknowledge those in Nashville who were incredibly supportive. George Barrett welcomed me with dozens of stories and insights, and I thank him for his boundless generosity (and for the cigars). Don Doyle and Marjorie Spruill graciously opened their home during a summer of research, making an immense difference during my Nashville jaunt. Pete Kuryla and Bob Hutton were especially fantastic in welcoming me to the city, talking shop and hilarious nonsense in equally entertaining measure. And I am most appreciative of those who were agreeable to being interviewed or pointed me in new directions. Similarly, I cannot thank enough all the fantastic archivists who rolled up their sleeves and

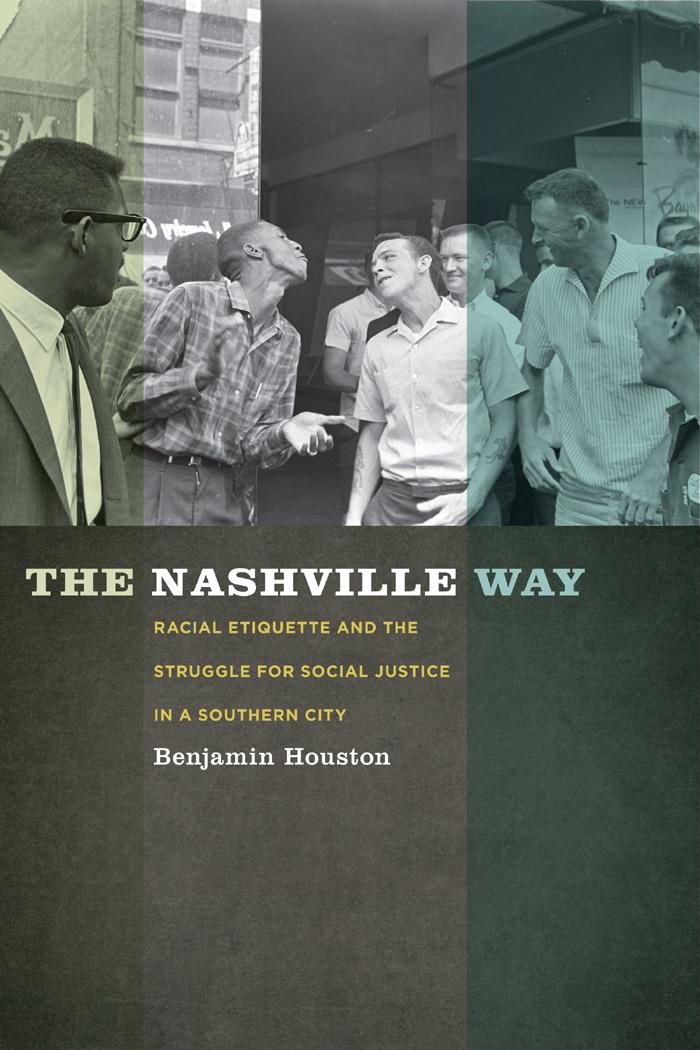

helped a rookie researcher immerse myself in Nashville’s documentation. I particularly am grateful to Kathy Smith and Teresa Gray at Vanderbilt, Beth Howse at Fisk, Ken Fieth at the Nashville Metro Archives, Kathy Bennett and Sue Loper at the Nashville Public Library, and Chris Harter at Amistad Research Center. Beth Odle at the Nashville Public Library was particularly patient in helping me find the right photos for this book.

In direct and indirect ways, the driving interest in this book first stirred at Rhodes College. Tim Huebner saw something and worked indefatigably for my sake more than his, and I thank him for the belief. Russ Wigginton gave me a first peek at the civil rights movement; he and Doug Hatfield gave sage advice freely. Even before that, I carried a bit of Paul Hammock’s and Doreen Uhas-Sauer’s influence on me wherever I went, and still do—thank you for what you did. As a dissertation, this project was birthed at the History Department at the University of Florida, where I had the great fortune of working with great people and scholarteachers. Julian Pleasants is a good man and had my back in a number of ways. Roberta Peacock looked after me in many different ways. Bert Wyatt-Brown, Fitz Brundage, and Jack Davis were very good role models for me in various ways, and I thank them for their energy and support. And special thanks especially to mate and tireless mentor, Brian Ward.

I’m also grateful for all the uf gang: Jenny, Jace and Shannon, Craig and Amanda, Sonya and Barclay, Carmen, Bud and Theodora, Jason, Mike, Tim, Kristin, Randall, Kim, Bryan, Dave, and Chris—good times and fine people all the way around. Alan and Lynn were exceptional for their wisdom, caring, and hilarity, and triple thanks to Barclay for enduring all those damn e-mails. Professionally, I would also like to mention Wesley Hogan, Tony Badger, Ray Arsenault, Jane Dailey, Mike Foley, Bill Link, Ellie Shermer, Mike Ezra, Clive Webb, George Lewis and Liz Gritter for advice and good sense in varied capacities, as well as the good folks at the University of Georgia Press.

Working at the Carnegie Mellon’s Center for Africanamerican Urban Studies and the Economy was a tremendous first job. Thanks go to Joe Trotter, a fine man and consummate professional who taught me a lot. I’m also grateful to Tera Hunter, Johanna Fernandez, Edda Fields-Black, John Soluri, Nancy Aronson, Allen Hahn, and Jared Day for welcoming me to the school and the profession. Similar thanks go to Kevin, Russell, Lisa, and the rest of the graduate students for their cheerful energy, with special appreciation to Kate Chilton and Alex Bennett for able research assistance. Lisa Hazirjian and Derek Musgrove were especially splendid comrades/colleagues/friends and, in the case of “Gee, Derek,” a sorry excuse for a beer drinker but a very fine voicemail leaver.

x · ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Shifting across the pond to teach in England has landed me among a lot of amazing people. Hot-water bottles were just the start from Martin Dusinberre, but now that I’ve thanked him in print, I can stop checking my phone and he can stop killing me in squash. Saying thank you is simply inadequate for Joe Street, Martin F., Felix, Xavier, Asuka, Susan-Mary, Carolyn, Lorenzo, Matt, Monica, Alex, Sam, Claudia, Joan, Tim, Samiksha, Di, Kate, Mike, David, and Scott, but I hope they know that I mean it. Thanks also to the Friday footy crew for enduring my sad attempts at being a striker and for the ales afterward. Now that the book is done, I can safely exhort: “Long live Big W”!

On a more personal note: thanks to Melanie Sylvan, Heather Sebring, Andrew Vlahutin, Christine Leong, B.J. and Andrea Yurcisin, and Brandon and Trudy Barr for letting me crash on sofas during various research trips and always being there, in so many rich and amazing ways. Thanks for reminding me where I came from and where I could go. Much love to Nikolai and Ellen, who more than anyone can keep me balanced (and I’m sorry about the printer), and to Lori for the e-mails, laughter, and moral support. This book is dedicated to Robert J. Houston and Evelyn Yurcisin Houston, my parents. Both of them taught me about history in very different but hugely important ways. Their sustenance and love was manifested every day in a thousand large and small examples.

And finally: Michelle. It’s not just any person who on any given day can and will proofread my chapters, give me a yoga lesson, help me thrash out ideas over a pint, or bring me countless cups of coffee as I furiously pound away on a keyboard. That’s just a fraction of what she does. Yet, who she is, and what she has brought to my life, is even more luminous.

This page intentionally left blank

The Nashville Way

These aberrations are kept going more by unwritten and un-writable laws than by the written law affecting the races: by an immense and elaborate code of etiquette that governs their daily relations; by an exquisite and intuitive tact on the part of both whites and Negroes; by adherence to a labyrinthine code of manners, taboos and conventions. There is therefore a sense of strain in the air, of a delicately poised equilibrium of forces held in leash. Here men toss uneasily at night, and awake fatigued in the morning. —David L. Cohn, “How the South Feels,” 1944

Among all the vivid examples of Jim Crow– style segregation in the South, some of the ugliest were the stark white and colored signs paired with shiny or shabby restrooms and water fountains. As powerful symbols of the racial divide, these markers were all the more chilling for being so casual. And yet, for someone strolling through downtown Nashville in the 1940s, those signs were not always there, forcing the visitor to chart a far more bewildering path. No white or colored designations adorned the restrooms in the state capitol, for example. Nor were there any in the post office, where both races waited in line together—although the watchful eye would note that black postal employees always worked in the back room under white supervision but never at the service window.

Walking through the city-county building downtown, however, yielded mixed messages. The upper floor did have segregated restrooms, but no one bothered to ensure that people obeyed the mandate. The first floor instead had what used to be a colored sign, painted over because of a lack of white facilities, alongside a water fountain used by both races. Similarly, in one railway station where some whites worked side by side with blacks, the restrooms were segregated but “similarly equipped” and a common water fountain served both races. At the customs house, the colored restroom for black employees was considered well-appointed despite being segregated—but the public restrooms and water fountains were used

by both races. For audiences at the city auditorium, the color line switched invisibly depending on the crowd: sometimes blacks were relegated to balconies, but other times both floors were divided, with the poorer of both races up in the cheaper seats. And while Nashville courtrooms did not have racially designated seating, “Negroes always discreetly leave a foot or more of space between themselves and whites.”

In myriad ways, an important aspect of race’s legacy in modern U.S. history is how space and place were preserved or rearranged by whites and African Americans in large and small dimensions. As both races went about their lives, the South’s social dynamics loomed conspicuously in even the most routine interracial interaction. In a Nashville courtroom, the quiet use of gaps between people seated on a bench had far deeper meaning as an expression of social distance. But, on a vaster scale, the molding of various spaces into black and white neighborhoods told equally important stories about how economic and political clout constructed laws and public policies that shaped and reflected the social dynamics of Nashville. This book is an account of how two races in one city, with a shared history yet divergent paths, utilized and fought over social and physical space in diverse ways. Within that story is a bigger tale about the urban South most immediately, U.S. history more generally, and particularly how racial legacies remain in the present. Even as the turbulent years of the modern civil-rights era altered laws and customs, the patterns of segregation, in reforming, retained resonance with the past.

It may seem surprising that Nashville’s story is at least somewhat analogous with other southern—and, indeed, U.S.—places given that Nashville boosters relentlessly conveyed a sense of the city’s uniqueness, often in cheery nicknames. For example, “The Rock City” derived from its perch atop graceful limestone cliffs with the Cumberland River meandering through the gentle hilly landscape of middle Tennessee below. “The Protestant Vatican” invokes Nashville’s religiosity, as the city to this day has numerous churches and headquarters several major denominational institutions. Similarly, “The Athens of the South” refers to the city’s seventeen colleges and universities, many of them religiously affiliated, and locals even built a full-scale replica of the Parthenon in homage to this appellation. “The Wall Street of the South” tips a hat to the banks and insurance companies responsible for Nashville’s prosperity. Taken together, these appellations epitomized Nashville’s religious, educated, and white-collar character. More recently, “Music City, U.S.A.” acknowledges Nashville’s heritage in fostering and capitalizing on the rich tradition of country music.

Because Nashville’s elite had such fervent pride in the city’s image, it was startling when someone tried to puncture these affectations. This happened in July 1945 when white Nashville educator J. E. Windrow addressed the Kiwanis Club

and lauded Nashville as “the ideal city” and the “queen city of culture,” with “all the ingredients of civilized society,” where “at last is found man at his best.” But Windrow immediately deflated these glowing plaudits with a lengthy list of Nashville’s problems: the smoke smothering the city skyline, the “civil lethargy” represented by voter apathy, the “staggering death rate” of tuberculosis victims, and assorted social ills such as high venereal disease rates, infestations of flea-ridden rats, inadequate garbage collection, juvenile delinquency, and poor housing, sanitation, and sewage. Disgusted with the inaction of Nashville’s professors and civic clubs in confronting such problems, Windrow chided those who “buried their heads in the sands of the magnolia-scented past.”

Windrow’s critique suggested that Nashville’s slogans give only superficial glimpses into the city’s character. Many stress instead that understanding Nashville requires grasping the city’s inherent paradoxes. One observer, traveling through Tennessee in 1962, noted that “It is difficult to believe one state can have such different ‘moods.’ ” Nashville personified this as the capital city in the middle of a state adjoining eight others. The city stood geographically at a crossroads roughly equidistant between border and Deep South, and likewise between the cool rugged mountains around Chattanooga and the flat scorching Delta surrounding Memphis. One historian and resident of the city used the same term in writing that Nashville is “as much a mood as it is a place,” as it commingled remnants of a self-professed “genteel Old South” and “reminders of a Confederate heritage” with the “bustle of a New South commercial town,” the bawdiness of a river city and the fundamentalist roots of a religious center, an urban lifestyle and the homespun country values of rural people tied to the land. As the city’s elites built the trappings of a major urban center (sophisticated political leadership, art galleries, a symphony, renowned institutions of higher education, reputable newspapers), rural migrants of both races from surrounding counties in Middle Tennessee, South Kentucky, and North Alabama flocked to Nashville, searching for more lucrative work or more fun in hardscrabble lives. Even Nashville’s fledgling country music scene grew from uncertain parenthood, mixing sharecropper’s blues migrating east from Memphis with Appalachian folk music filtering west. Never mind that Nashville’s best citizens sniffed haughtily at the unwashed crowds who littered outside fine churches before cramming into the pews of a hillbilly show called the Grand Ole Opry. The city housed all these paradoxes and more; anyone looking to comprehend Nashville’s history must hold these tensions in place—rural and urban, polished elites and gritty common folk, a backwardlooking past and a forward-looking gaze—to discern the city’s character. When Windrow spoke in 1945, he addressed changing political shifts in the city. But the internal contradictions he identified were especially apparent as Nash-

ville grappled with tumultuous racial issues during the post–World War II era. Here, too, another slogan, “The Nashville Way,” captured the self-professed style of Tennessee’s capital city, where pride, provincialism, and paternalism melded in powerful ways. Nashville’s boosters trumpeted amicable race relations as a city virtue and recourse to catch-phrase characterization was tempting. “In Nashville, we don’t have race relations, we have human relations!” Mayor Ben West crowed in the 1950s. “Nashville’s segregation,” remembered local white journalist David Halberstam, “was largely of a soft kind, administered, it sometimes seemed, not with the passion of angry racist officials, but more as a cultural leftover from the past.”

In the vernacular of the time, Nashville was a moderate city. Even those casually familiar with the dynamics of southern race relations will recognize this word and its synonyms civil, progressive, genteel, and respectable, all used widely throughout the South. Traditionally, these words were all different hues of the same color; they corresponded to an upper-class emphasis on manners, decorum, and a hypersensitive avoidance of civic unrest. Moderation meant a more or less genuine sympathy for black advancement undergirded by deeply felt assumptions of black inferiority and white superiority. This combination, taken for granted by white southerners in the mid-twentieth century, remained so deeply ingrained that it barely needed conscious consideration or even acknowledgment. As historian William Chafe puts it precisely, it was “a paternalism so unconscious it would never be called such by whites.” Moderation was used frequently to depict a racial stance that positioned itself between sweeping declarations of vicious racism and the sanctioning of racial equality, defining itself against extremism rather than for a particular racial philosophy. Thus the moderate philosophy had no internal cohesion in steering between two powerful poles of racial thinking: avoiding the vituperative racism of hard-core segregationists, but often equally skeptical about southern racial progressives. Essentially, moderates were segregationists—segregation was, after all, what they had been raised on, taught, and acculturated to, and the prospect of an integrated society confounded their imagination—but the style with which they professed their racial superiority differed from other whites.

For black southerners, who knew more about the agonies of segregation than whites ever could, moderation was empty and self-serving rhetoric, and black Nashvillians especially knew better than to accept local platitudes about race. Local observers dismissed the collective back-patting of white moderates as superficial, noting that “[Nashville’s white] citizens are constantly under the temptation to glory in the past when present problems seem too much for them.” They saw moderate discussions, even those under the auspices of interracial cooperation, as rarely yielding concrete or significant change. Instead, “the tendency is to talk over local problems so much that we think we talk them out of existence.” The

irony was that Nashville’s black community, despite segregated realities, were fundamental to the qualities that white Nashville took such pride in: the prominent African American colleges and universities in Nashville were part of the “Athens of the South,” black banks and businesses were a small but notable component of the “Wall Street of the South,” and black religious institutions part of the “Protestant Vatican.” These black institutions cultivated resultant values among African Americans in Nashville in much the same way that white Nashville did.

It is significant, then, that there was an identifiable black “Nashville Way” that looms prominently in civil rights movement history—as movement veteran John Lewis later recalled, “something happened in Nashville that did not happen any other place in America.” In 1960, as lunch-counter sit-ins swept the South, Nashvillians found their city home to a unique cohort of demonstrators, most from elsewhere but uniquely incubated in this environment. Perhaps more than any other cluster of civil rights activists, this Nashville-based group fused African American religious tradition with a number of different intellectual influences in absorbing the philosophy and meaning behind nonviolent direct action and adopting it as a way of life rather than as a mere tactic. Thus emboldened, these Nashvillians later played crucial roles in founding the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (sncc), rescuing the 1961 Freedom Rides, and participating in virtually every major subsequent southern battle of the movement, including those in Jackson, Birmingham, and Selma. Although the absolute quality inherent in this conception of the movement’s possibilities frequently jarred with more pragmatically inclined civil rights veterans, the Nashvillians comprised, in many ways, both the literal and figurative soul of this phase of the black freedom struggle. The 1960 sit-ins began in other states, argues activist C. T. Vivian, “but the Movement began here in Nashville.”

Thus more paradoxes: the carefully mannered representative politeness of the white Nashville Way and the uniquely daring, radical, and transformative possibilities of the black Nashville Way both sprang from the same city. This book attempts to explore both Nashville Ways, their origins and trajectories, and the results when the two clashed. Both ways were styles of belief and action that shed light on southern urban racial dynamics during the civil rights era. All the self-clichés about white Nashville’s culture and pretensions of mannered graciousness, the self-image as a city that retained the finest aspects of the Old South’s “magnoliascented past” while adapting to the best elements of progress and change, signaled the unspoken belief that race relations could be managed, that the Southern Way of Life could adapt without sacrificing core elements. The laid-back political and business climate in white Nashville made for a functional approach to race relations that begrudgingly dealt with immediate conflicts while resisting structural,

functional, and comprehensive change. And, by claiming Nashville as a good city for black people, white Nashvillians were able to downplay and deemphasize civic issues that had profound racial implications for the city. Conversely, the unusual example of nonviolence in Nashville highlights longer trends within black Nashville, as African Americans sought refuge in the same virtues of civic pride and personal respectability while still challenging white Nashvillians to match moderate rhetoric with substantive action. That internal tensions within the black community, much like the white, dictated the course of racial activism was another critical part of the story. Thus some shared values smoothed over what was a deeper racial reality of constant contentiousness between and within the races. This tension between Nashville’s rhetoric and Nashville’s actions—and how integration did or did not occur across the city—is the core theme of this book.

The Nashville Way argues that both civil rights activism and white responses to battles over jobs and public accommodations sprang from the elaborate racial etiquette of the Jim Crow past and were updated according to new circumstances decades later. This etiquette simultaneously provided whites with self-justification for their racial beliefs while channeling black resistance. But a combination of legal and political maneuvers in the mid-1950s, responding to movement endeavors and accelerating throughout the 1960s, changed the rules. Whether by explicit design or benign indifference, this maneuvering remapped the spatial layout of the city so that race and class remained deeply encoded in the physical layout of the city. To be sure, this had happened consistently throughout the twentieth century as neighborhoods around the city changed racial demographics according to the demands of white businesses and politicians. It was not only a case of white flight to suburbs, although that happened in droves, but a combination of city policies that directly targeted black neighborhoods and institutions where movement activism had flourished. As the racial etiquette of the first half of the century was meant to preserve social hierarchies in the spaces where the races interacted, so did the second half of the century see whites dictating the same in terms of the city’s physical design to preclude that sort of interaction. Both were meant to reinforce black economic dependence on whites. Whites reshaped urban space as the blacks, however fitfully, began to break out of their “place”; despite the change in etiquette, the structural dimensions of segregation were reinforced in analogous ways.

These conflicts between rhetoric and action, racial law and racial custom, space and place, were just some of the tensions embedded in the Jim Crow racial order before this book begins. Nashville’s racial culture drew directly from the wider socioeconomic makeup of the city, but this was part of an ongoing reality that most urban U.S. locales during the twentieth century were struggling between traditional and progressive impulses more broadly in negotiating shifting economic

contexts. By 1945, Nashville was a major city regionally, although less so nationally, lagging behind Atlanta and Birmingham in attracting industry. Instead, the local economy depended on shipping and distribution businesses plus local banking and insurance companies that were regional powerhouses. Conservative mentalities governed white businessmen in these years, especially with a distinctive laggardly attitude toward interfering in political and social affairs, and racial matters in particular.

While white Nashville was happy to make its peace with the New South in economic terms, its conservatism aligned naturally with a cultural harkening back to the Old South. If Atlanta was “the city too busy to hate,” Nashville may well have termed itself “the city too well-bred to hate.” Like Atlanta’s motto, that was Nashville’s white lie, even though it spoke to a certain attitude that was historically rooted. But this lie not only obscured the hateful behavior of many in the city, it also soft-pedaled the reality that racism could be driven by attitudes other than mere hatred. Jim Crow had been designed to force African Americans to stage public deference to supposed white superiority. When that insufficiently cowed black resistance, segregation was shored up with repressive racial laws so as to normalize white supremacy publicly in daily life as an added insult to the economic subjugation and violent repression of African Americans. Indeed, at the time, segregation was considered a quite progressive measure that hoped to tame violent racial passions into an orderly disaggregating of racial privilege, particularly in cities where racial interaction was frequent.

But African Americans in Nashville did not stand for mere flattery. By World War II, even as segregation’s cultural hold powerfully controlled the white mind, there were some signs of erosion elsewhere. Nashville’s downtown and underworld were realms where racial interaction occurred in uncertain ways, often weakly or shamefully defended by whites or not at all. Connections between black and white Nashville existed in business and politics—never on an equal plane but, in those connecting places, the racial etiquette of the past held sway. As John W. Cell pointed out, “Jim Crow was a city slicker”—the etiquette was built to preserve distinctions in these realms of racial intersections. Segregated life in Nashville built diverse black populations that fought this etiquette as well as more tangible battles against segregation simultaneously in individual and collective ways. Even as African Americans shrewdly learned to play the game of racial etiquette according to different rules by trading off opportunities for individual survival, the game was still rigged to reaffirm the broader system of segregation and allow whites to luxuriate in their false sense of racial superiority.

This contradiction is captured as chapter 1 surveys the social and political dynamics of Nashville from the late 1930s into the mid-1950s, when racial etiquette

had a fluid yet formidable hold on Nashville. The chapter endeavors to capture the lived reality for both whites and blacks in one segregated society. It emphasizes both the racial etiquette that governed the behavior of both races, as well as the spatial layout of the city’s urban segregation patterns, in order to give a full picture of life under Jim Crow. Chapter 1 also introduces some personalities key to Nashville’s history to show how these figures represented networks of interracial progressives and white conservatives contesting each other over racial issues. All these elements form crucial context for understanding the racial fissures that subsequently develop.

As various versions of grassroots activism in Nashville blossomed into a fullscale movement, black Nashvillians fought segregated mentalities directly in the struggle over public education and public accommodations, along with scores of other battles for better employment opportunities, enhanced voting power, and access to social, political, and economic equality. Chapter 2 is an account of public school desegregation in Nashville during the mid- and late 1950s, the process of which yielded “The Nashville Plan,” a model for other southern communities. The chapter focuses particularly on how self-proclaimed white moderates struggled with, and ultimately largely succeeded in, dictating the terms and pace of school desegregation.

After white moderates controlled school desegregation, the local movement had its most triumphant achievement during the 1960 lunch-counter sit-ins explored in chapter 3. Here, diverse tactics and personalities harmonized in pursuit of a common goal by playing directly on the hypocrisies and distortions of Nashville’s racial etiquette and making Nashville a different model, now one that showcased the possibilities of disciplined nonviolent direct action. But equally importantly, the sit-ins forged a collectivity in black Nashville that would not be duplicated thereafter. Perhaps more importantly, beyond the stirring moral call of nonviolence and the militancy in seeing nonviolence as a way of life, the campaign united and directed the political and economic power of black Nashville—significant enough to be compelling—toward a single target.

This exceptional moment, and the following battles that continued throughout the 1960s, resulted in unrelenting and constant violent outbursts meant to thwart movement ambitions on a level that few accounts in Nashville then and now dared to acknowledge openly. Chapter 4 brings the themes of chapters 2 and 3 together in surveying ongoing civil rights struggles up to the mid-1960s as activists struggled to extend the lessons and possibilities of the lunch-counter sit-ins into other arenas. Subtle changes in white resistance, continued attempts to sustain the movement, and detailed patterns of how desegregation actually occurred show the mixed results of racial change in these years. The outbursts on some level were ac-

knowledgment that blacks were no longer following the script and that the racial etiquette of the past was fading. Slowly chipping away, the movement scored some victories in the downtown spaces where whites were vulnerable. Other realms such as employment or social clubs were far harder, as whites had little compelling reason to share social space or hierarchy with blacks. But with these developments came a reframing of rhetoric and values from whites besieged by black activism. Whether couched in the usual terms of “freedom of association” and “color blindness,” whites tried to use legal and social norms to mask the consistent violence on Nashville streets, to change the conversation to a more elevated tone, and to retain some control over a situation unsettled by African American activism.

Chapter 5 is based on a racial disturbance nominally triggered by Black Power advocate Stokely Carmichael’s visit to the city in April 1967, but also depicts how broader issues of class and generational differences pulled factions apart as the city continued desegregating unevenly and uneasily. As the 1960s continued, Black Power—which never had particularly vibrant and organized roots in Nashville despite its appeals—became an excuse for an era of racial politics where whites had new rationales for controlling and dominating black space while stigmatizing black standards. Along with these shifts in racial attitudes and rhetoric came applications of laws and public policies that not only defended against black activism but attacked it directly by targeting the places that had bred the activism. In the Black Power years, a new cohort of black student activists staged symbolic confrontations similar to those in 1960 but according to the new ethos of the era. This was, however, marginalized by the law and order compulsions of the white power structure and students dismissive of differing outlooks from Nashville’s black elite. Yet, even as the black elite dampened Black Power spirit in the city, they found themselves vulnerable to wholesale changes that targeted the black economic power directly. How this occurred is treated in chapter 6 as battles over the building of Interstate 40, the local Model Cities program, and the issue of busing all factored into a reshaping of the city that preserved legacies of a racial past.

By knitting these episodes into a fuller analysis, The Nashville Way straddles and tries to merge several different scholarly conversations among historians of the urban South and civil rights movement. Such an approach is meant to meld the various historiographies into something more than the sum of isolated yet important themes and use the Nashville Ways to embody how both racial attitudes and racial policies molded the history of this era. This book readily falls within the genre of civil rights community studies, which favor in-depth portraits of individual cities to yield a fine-grained look at how both black activism and white resistance functioned and responded to each other. Like all types of historical scholarship, community studies have inherent strengths and drawbacks. They help

provide a useful way to evaluate results—namely, the extent to which the movement spurred change. Focusing on one city also provides the chance to render the sheer range of issues and dynamics against which the movement struggled and to underscore the interplay between individual agency and broader forces. Above all else, this book was profoundly influenced and inspired by William Chafe’s classic Civilities and Civil Rights, which described the progressive mystique that governed white moderate attitudes in Greensboro, North Carolina—an attitude synonymous with Nashville’s moderation. My work extends Chafe’s formulations by exploring the class dimensions inherent in moderate civilities, by underscoring the constancy of violence that undergirded those civilities, and by linking those attitudes to wider-scale use of legal means to buttress segregation.

But, to fully render how the Nashville Ways operated, it was necessary to draw from other literatures. In particular, studies about the intricate etiquette that comprised elements of the Jim Crow– era South’s racial culture gave insights that applied to the civil rights era when that etiquette was directly under siege. Numerous scholars have underscored how, from its inception, Jim Crow segregation was part of a defensive maneuvering on the part of whites who tried multiple cruel ways to control race relations (and thus political and economic power) as they faced African Americans who refused to surrender to such machinations. The parameters that these scholars trace in sketching how racial etiquette was inculcated, taught, and defended with unrelenting and targeted violence by whites against diverse forms of resistance from African Americans are important to depicting how white and black Nashvillians interpreted their own world. But this book also connects to the post– Jim Crow South and the recent body of historical literature that joins suburban growth and urban changes with race to highlight how the Sunbelt politics of suburbanizing whites drove much of the political, economic, and social history of post–World War II America. Those developments are also Nashville’s. White supremacy was updated, moderated, and restrengthened across the South and indeed America, regardless of the “flavor” or “mood” of each place, precisely because of the persistence of movement activism. Place did matter, even as the universal pattern also held true.

Uniting these literatures is necessary to combine black and white realities into one narrative that can better highlight the fullest scope of segregation in U.S. life. My emphasis on southern racial etiquette is meant to depict how a racial culture was made, but, in doing so, I do not mean to downplay the reality that the segregated customs embedded in racial etiquette (however “soft,” as Halberstam ascribed to Nashville) were only the most superficial and visible components to a far more abusive system. Indeed, Jim Crow was fundamentally brutal, violent, and exploitative in shadowing every aspect of southern life. This book is meant to high-

light this enduring reality as the real legacy lurking underneath Nashville’s selfpromotional tendencies about matters of race.

Frequently people who lived through this era remark on how life was “totally segregated,” as they try to capture the staggering weight of an entire society where racial divisions were stark, unrelenting, and powerfully informed individual destinies. But, even as that view of Nashville or any other place being “totally segregated” highlights the enormity and scale of Jim Crow, the phrase also tends to downplay or minimize how segregated life functioned on an intricate day-to-day level. Racial etiquette dictated that the social realities of race, class, and gender dynamics in southern racial culture were ever-present in everyday life and underscored how people thought about, internalized, and made choices about race. And, as racial etiquette helped dictate social norms, an entire society was predicated on racial values that were falsehoods made terrifyingly real and, especially when reinforced with laws, molded into the fabric of everyday life.

Writing a narrative that encompasses the stories of blacks fighting this reality even as whites reconstructed these fictions is important, but only if we understand that these stories should encompass everything from daily encounters on a Nashville street to how the building of those streets happened in racially specific ways. This approach is necessary to appreciate how the South’s racial culture mattered to blacks and whites, how both were inured to and thus shaped by segregation in varied ways, and how that framed their beliefs and decisions about responding to immense social change. And yet, individual decisions come from available options, many of which are dictated by laws, political norms, and public policies that construct our world in seemingly invisible ways yet with profound consequences, even when created by individuals shaped by racial etiquette. Both factors are critical dimensions to understand how legacies of the racial past live in the present. In a sense, then, this book connects the cultural paradoxes of the white moderate South with the racial reorganization of urban space due to the insistent pressures from African American activism. The culture of segregation, borne from generations weaned on Jim Crow and acted out in daily racial etiquette that reinforced such attitudes, was replicated on a citywide scale as whites reacted defensively to black pressures, first over social distance in public accommodation (and other civil rights issues) and later over the physical remapping of the city itself.

When I began teaching history in graduate school, I found myself troubled by student essays exploring the civil rights movement with great sophistication but concluding that those days of discrimination were now banished to the past. In many ways, this book is meant to address that inference. By using Nashville and the respective Nashville Ways as microcosms of racial attitudes and racial arenas,

I hope to use both dramatic and prosaic events to capture the tensions between blacks and whites during this time and place, and explore how decades of local and national issues fraught with racial meaning filtered through black and white lenses differently to condition events and attitudes. The details in these pages are meant to preserve the richness of Nashville’s particulars while still speaking to the broader themes that animate the city’s racial history and carry the most resonance for historians and citizens. There are undoubtedly stories about race in Nashville that will still need to be told. Rather than being exhaustively comprehensive, my approach hopes to portray faithfully the perspectives of those people who lived this history while binding these individual stories into something more connected and meaningful. It is a difficult balance and one that I hope I have honored. What follows is tied to one specific locale, drawn from local events and personalities, but is also meant as much more. It is the story of a society wrestling with and yet willfully ignoring its racial reality. Most fundamentally, it is the story of how a racial status quo, after decades of upheaval, was both changed and yet preserved.