1

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP, United Kingdom

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries

© Oxford University Press 2019

The moral rights of the authors have been asserted

First Edition published in 2019

Impression: 1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Data available

Library of Congress Control Number: 2018948522

ISBN 978–0–19–876638–4 (hbk.)

ISBN 978–0–19–876642–1 (pbk.)

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780198766384.001.0001

Printed in Great Britain by Bell & Bain Ltd., Glasgow

Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. Oxford disclaims any responsibility for the materials contained in any third party website referenced in this work.

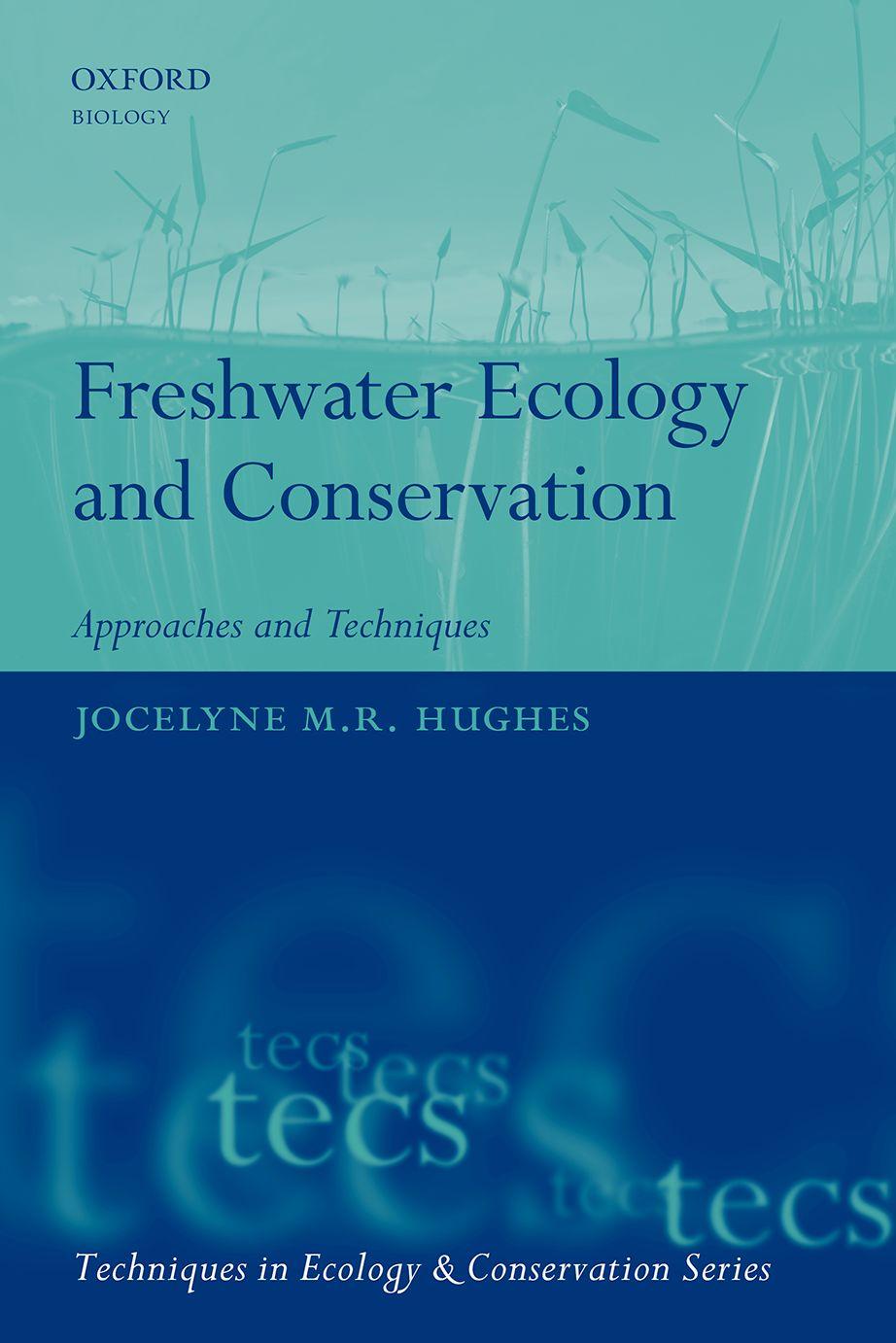

Preface

Water underpins all life on Earth, and in particular, hydrology and water chemistry play a signature role in maintaining the structure and function of freshwater ecosystems. Despite the manifest importance of freshwater, and the human dependence on healthy freshwater ecosystems, wetlands have continued to be degraded, polluted, and drained, and freshwater species have declined at an alarming rate—for example, the well-documented decline of global amphibians. This book aims to provide a comprehensive and concise synthesis of the vast literature on the techniques used in freshwater ecology and conservation that is currently dispersed globally in manuals, toolkits, journals, handbooks, ‘grey’ literature, and websites. It should be regarded as a ‘book of books’, and it is on this basis that the late Brian Moss encouraged me to carry out the project. The book is intended to provide a thorough understanding of different approaches and techniques needed for successful research, management, and conservation of freshwater ecosystems. Freshwater conservationists and practitioners often need to understand hydrochemical storages and fluxes in wetlands, the physical processes influencing freshwaters at the catchment and landscape scale, and the hydrochemical processes that maintain species assemblages and their dynamics. Conservation builds on a sound ecological framework, in which each species must be examined at the individual, community, and catchment level of interaction, and in which human interactions with freshwaters are a critical part. The survey approaches and techniques used, and the subsequent analytical methods, directly affect the interpretation of results, and it is essential to understand their limitations or biases in order to make informed decisions on conservation and management. This book cannot list all techniques used to survey or sample freshwaters—that is an impossible task; rather, it presents some of the practical approaches that are used in freshwater ecological research and surveys, and, using examples from international studies, synthesises why certain methods are used in preference to others for particular types of freshwater habitat or particular types of organism, or for measuring, documenting, and evaluating the dynamics and management of the ecosystem. Central to all freshwater surveys is the identification of organisms to the species level. This book does not attempt to cover identification and taxonomy although passing reference is made to new methods in species identification in some chapters.

The book is divided into three parts. The first part is an overview, presenting an outline of the diversity of freshwater ecosystems; the importance of hydrology and water chemistry in driving ecosystem processes; the different approaches required to answer questions in freshwater ecology and provide effective solutions to conservation problems, including the essential nexus between scientists, social scientists, and stakeholder participation; and an overview of sampling strategies and protocols used in freshwater investigations. The second part describes the techniques needed to quantify the individual physical and biological components of the ecosystem, including, for

example, water quantity, water chemistry, aquatic plants, aquatic animals, and algae. This section summarises the huge array of approaches and techniques used for surveying and measuring the multitude of organisms to be found in freshwaters and their physical environment, and that are needed to answer questions on—for example— species richness and abundance, species hydrochemical preferences and tolerances, or the impacts of human populations on freshwater ecosystems. The final part deals with the bigger picture in conservation and management and the approaches needed to answer complex questions involving different stakeholders. It brings together the different approaches and techniques needed to understand interactions between the physical and biological components of freshwater ecosystems, changes over time and ecosystem dynamics, human dependency on and interactions with freshwaters, and the conservation, management, and evaluation of these ecosystems. Individual chapters synthesise approaches and methods drawn from science, economics, landscape management, and engineering; for example, evaluating the restoration of eutrophic waters, monitoring the spread and control of non-native invasive species, and quantifying ecosystem services.

I would like to thank the people who assisted in the production of this book— in reviewing, editing, discussing the contents, making suggestions, and providing moral support: Flora Botsford, David Bradley, Ana Castro Castellon, C. Ken Dodd Jr., the late Mike Edmunds, François Edwards, Max Finlayson, Dustin Garrick, Thomas Hesselberg, Francine Hughes, Lizzy Jeffers, Tim Johns, Curt Lamberth, the late Brian Moss, Liz Sanders, Carl Sayer, Rebecca Tharme, Jennie Whinam; seven anonymous referees; and the fantastic team of lead authors and co-authors who contributed to this book and helped with the reviewing. I would like to thank my previous department at Oxford—the Department for Continuing Education—that supported a six-month sabbatical that enabled me to focus on developing this book. I am so grateful to the inspirational, international students I teach on the MSc in Water Science, Policy and Management, the Postgraduate Certificate in Ecological Survey Techniques, and the Postgraduate Diploma in International Wildlife Conservation Practice at the University of Oxford, who are justification alone for this project and have taught me the vital importance of training early career researchers and practitioners in field skills, practical surveys, and analytical methods. I would like to thank Lydia Shinoj and Paul Nash at SPi Global for their infinite patience. At Oxford University Press I would like to thank Bethany Kershaw, Lucy Nash, and Ian Sherman; and the overall editor of the Techniques in Ecology and Conservation Series, Bill Sutherland, for giving me the chance of steering this project. Finally, I could not have completed this volume without the infinite support of my beloved family: my life-long partner Charles, and our children George, Madeleine, and Fifi; and my parents, Arlette and Gren, and parent-in-law, Alison, who all three passed away during the production of the book and to whom I dedicate it.

Jocelyne Hughes Department of Geography and the Environment, University of Oxford

2.4

2.4.1

2.4.2

Leon A. Barmuta

3.1

3.2

3.3

3.4

4.4

4.3.3

4.3.4

Nic Pacini, Libor Pechar, and David M. Harper

7.

5.2

5.3

5.3.1

5.3.2

5.3.3

5.4

5.4.1

6.2

6.2.1

6.3

6.3.1

6.4

6.4.2

6.4.3

6.4.4

6.5

6.5.1

6.5.2

6.5.3

6.5.4

6.6

7.1

7.2 Diversity of freshwater algae

7.3 Standing (lentic) and flowing (lotic) waters

7.3.1 The balance between planktonic and benthic algae

7.4 Phytoplankton

7.4.1 Phytoplankton

7.4.2 Phytoplankton

7.4.3

7.5 Substratum-associated algae: from biofilm to benthic communities

7.5.1 Biofilms

7.5.2

7.6 Assessment of eutrophication and control of nuisance algae in standing waters

7.6.1

7.6.2

7.6.3

7.6.4

7.7

8.2.3

8.2.4

8.3

8.4 Sampling

8.4.1

8.4.2

8.4.3

8.5 Bioindicators

8.6

8.6.1

8.6.2

9. Wetland Plants and Aquatic Macrophytes

Jocelyne M.R. Hughes, Beverley R. Clarkson, Ana T. Castro-Castellon, and Laura L. Hess

9.1 Introduction—Why survey vegetation in freshwaters?

9.2 Planning

9.2.1

9.2.2

9.3 Techniques and equipment specific

9.3.1 Equipment—grab and grapnel

9.3.2 Observation—bathyscope, snorkelling, and underwater camera

9.3.3 Detection—hydroacoustics and eDNA

9.4 Sampling strategies for freshwater plant surveys

9.4.1

9.4.2

9.4.3

9.5

9.6

9.7 What questions can these methods answer?

9.7.1

9.7.2

9.7.3

9.7.4

9.7.5

9.7.6

10. Freshwater Vertebrates: An overview of survey design and

Stephen E.W. Green, Rosie D. Salazar, Gillian Gilbert, Andrew S. Buxton, Danielle L. Gilroy, Thierry Oberdorff, and Lauren A. Harrington

10.1

Richard Marchant and Catherine M. Yule

11.3

Part III Ecosystem Dynamics, Conservation, and Management

12. Freshwater Populations, Interactions, and Networks

David M. Harper and Nic Pacini

12.3

12.3.1

12.3.3

13. Changes Over Time

Peter A. Gell, Marie-Elodie Perga, and C. Max Finlayson

13.3

13.4

13.5

14. Secondary Data: Taking advantage of existing

Aaike De Wever, Astrid Schmidt-Kloiber, Vanessa Bremerich, and Joerg Freyhof

15. Freshwater Ecosystem Services and Functions

C. Max Finlayson, Rudolph S. de Groot, Francine M.R. Hughes, and Caroline A. Sullivan 15.1

16. Invasive Aquatic Species

Julie A. Coetzee, Martin P. Hill, Andreas Hussner, Ana L. Nunes, and Olaf L.F. Weyl

17. Freshwater Ecosystem Security and Climate Change

Jamie Pittock, C. Max

and Simon Linke

18. Restoration of Freshwaters: Principles and practice

Carl Sayer, Helen Bennion, Angela Gurnell, Emma Goodyer, Donovan Kotze, and Richard Lindsay

18.1

18.4

18.6

19. Wetland Landscapes and Catchment Management

Caroline A. Sullivan, C. Max Finlayson, Elizabeth Heagney, Marie-Chantale Pelletier, Mike C. Acreman, and Jocelyne M.R. Hughes

19.1

19.6

List of Contributors

Mike C. Acreman Centre for Ecology and Hydrology, Maclean Building, Crowmarsh Gifford, Wallingford, OX10 8BB, UK.

Leon A. Barmuta School of Zoology, University of Tasmania, Hobart, 7001 Tasmania, Australia.

Helen Bennion Pond Restoration Research Group, Environmental Change Research Centre, Department of Geography, University College London, Gower Street, WC1E, UK.

Vanessa Bremerich Leibniz-Institute of Freshwater Ecology and Inland Fisheries, Müggelseedamm 310, 12587 Berlin, Germany.

Andrew S. Buxton Durrell Institute of Conservation and Ecology, School of Anthropology and Conservation, Marlowe Building, University of Kent, Canterbury, Kent, CT2 7NR, UK.

Ana T. Castro-Castellon Thames Water, Farmoor WTW, Cumnor Road, Farmoor, Oxford, OX2 9NS, UK.

Beverley R. Clarkson Landcare Research, Private Bag 3127, Hamilton 3240, New Zealand.

Julie A. Coetzee Centre for Biological Control, Department of Botany, Rhodes University, Grahamstown, 6140, South Africa.

John Conallin IHE Delft Institute for Water Education, Westvest 7, 2611 AX Delft, PO Box 3015, 2601 DA Delft, The Netherlands & Institute for Land Water and Society, Charles Sturt University, Elizabeth Mitchell Drive, Albury NSW, 2640, Australia.

Aaike De Wever Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences, Vautierstreet 29, 1000 Brussels, Belgium.

C. Max Finlayson Institute for Land, Water and Society, Charles Sturt University, Elizabeth Mitchell Drive, Albury NSW, 2640, Australia & IHE Delft, Institute for Water Education, Westvest 7, 2611 AX Delft, PO Box 3015, 2601 DA Delft, The Netherlands.

Joerg Freyhof Leibniz-Institute of Freshwater Ecology and Inland Fisheries, Müggelseedamm 310, 12587 Berlin, Germany.

Peter A. Gell Water Research Network, Federation University Australia, PO Box 663, Ballarat, 3350 Victoria, Australia.

Gillian Gilbert Royal Society for the Protection of Birds, South and West Scotland Regional Office, 10 Park Quadrant, Glasgow, G3 6BS, UK.

Danielle L. Gilroy School of Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of Manchester, Williamson Building, Oxford Road, Manchester, M13 9PL, UK.

Emma Goodyer IUCN UK Peatland Programme, c/o Harbour House, 110 Commercial Street, Edinburgh, EH6 6NF, UK.

Stephen E.W. Green Centre for Applied Zoology, Cornwall College Newquay, Wildflower Lane, Trenance Gardens, Newquay, Cornwall, TR7 2LZ, UK.

Rudolph S. de Groot Environmental Systems Analysis Group, Department of Environmental Sciences, Wageningen University and Research, 6700AA Wageningen, The Netherlands.

Angela Gurnell School of Geography, Queen Mary University of London, Mile End Road, E1 4NS, UK.

David M. Harper Emeritus Professor, University of Leicester, Adrian Building, University Road, LE1 7RH, UK.

Lauren A. Harrington Wildlife Conservation Research Unit, Department of Zoology, University of Oxford, Recanati-Kaplan Centre, Tubney House, Abingdon Road, Tubney, Abingdon, OX13 5QL, UK.

Elizabeth Heagney School of Environment, Science and Engineering, Southern Cross University, Lismore, New South Wales, 2480, Australia & Economic and Strategic Analysis Branch, NSW Office of Environment and Heritage, Sydney, New South Wales, 2000, Australia.

Laura L. Hess Earth Research Institute, 6832 Ellison Hall, University of California, Santa Barbara, CA 93106-3060, USA.

Martin P. Hill Centre for Biological Control, Department of Zoology and Entomology, Rhodes University, Grahamstown, 6140, South Africa.

Francine M.R. Hughes Animal and Environment Research Group, Department of Life Sciences, Anglia Ruskin University, Cambridge, CB1 1PT, UK.

Jocelyne M.R. Hughes School of Geography and the Environment, University of Oxford, South Parks Road, Oxford, OX1 3QY, UK.

Andreas Hussner Förderverein Feldberg-Uckermärkische Seen, 17268 Templin, Germany.

Donovan Kotze Centre for Water Resources Research, University of KwaZuluNatal, Scottsville 3209, South Africa.

Curt Lamberth University of Oxford, Wytham Woods, Woods Sawmill Yard, Wytham, Oxford, OX2 8QQ, UK.

Richard Lindsay Sustainability Research Institute, University of East London, Docklands Campus, University Way, London, E16 2RD,UK.

Simon Linke Australian Rivers Institute, Nathan Campus, Griffith University, 170 Kessels Road, Queensland 4111, Australia.

Richard Marchant Department of Entomology, Museum Victoria, GPO Box 666, Melbourne, Victoria 3001, Australia.

Matthew McCartney International Water Management Institute, c/o National Agriculture and Forestry Research Institute (NAFRI), Ban Nongviengkham, Xaythany District, Vientiane, Lao PDR.

G. Randy Milton Department of Natural Resources, Kentville, Nova Scotia, B4N 4E5, Canada & Institute for Land, Water and Society, Charles Sturt University, Elizabeth Mitchell Drive, Albury, 2640 NSW, Australia.

Ana L. Nunes Centre for Invasion Biology, Department of Botany and Zoology, University of Stellenbosch, Stellenbosch, South Africa; Centre for Invasion Biology, South African Institute for Aquatic Biodiversity, Grahamstown, 6139, South Africa & INNS Programme, South African National Biodiversity Institute, Kirstenbosch Research Centre, Cape Town, South Africa.

Thierry Oberdorff Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS), Institut de Recherche pour le Developpement, Laboratoire Évolution & Diversité Biologique, Université Toulouse III Paul Sabatier, 118 route de Narbonne, F-31062 Toulouse, France.

Nic Pacini Department of Environmental and Chemical Engineering, University of Calabria, Arcavacata di Rende, Italy & School of Geography, Geology and the Environment, University of Leicester, Leicester, UK.

Libor Pechar University of South Bohemia, Faculty of Agriculture, Applied Ecology Laboratory, Studentská 13, 370 05 Cöeské Budeöjovice, Czech Republic.

Marie-Chantale Pelletier School of Environment, Science and Engineering, Southern Cross University, Lismore, NSW 2480, Australia & Economic and Strategic Analysis Branch, NSW Office of Environment and Heritage, Sydney, 2000 NSW, Australia.

Marie-Elodie Perga Faculté des Géosciences et de l’Environnement, Institut des Dynamiques de la Surface Terrestre, University of Lausanne, CH-1015 Lausanne, Switzerland.

Jamie Pittock Fenner School of Environment and Society, The Australian National University, 48 Linnaeus Way, Acton, ACT 2600, Australia.

Julia Reiss Department of Life Sciences, Whitelands College, University of Roehampton, London, SW15 4JD, UK.

Rosie D. Salazar Science Area, Research Services, University of Oxford, Robert Hooke Building, Parks Road, Oxford, OX1 3PR, UK.

Carl Sayer Pond Restoration Research Group, Environmental Change Research Centre, Department of Geography, University College London, Gower Street, WC1E, UK.

Astrid Schmidt-Kloiber Institute of Hydrobiology and Aquatic Ecosystem Management, University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences, 1180 Vienna, Austria.

David C. Sigee School of Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of Manchester, Manchester, M13 9PL, UK.

Caroline A. Sullivan School of Environment, Science and Engineering, Southern Cross University, Lismore, NSW 2480, Australia & Marine Ecology Research Centre, Southern Cross University, Lismore, NSW 2480, Australia.

Rebecca E. Tharme Riverfutures Ltd, 48 Middle Row, Cressbrook, Derbyshire, SK17 8SX, UK & Australian Rivers Institute, Griffith University Nathan Campus, Queensland 4111, Australia.

David Tickner WWF-UK, Rufford House, Brewery Road, Woking, Surrey, GU21 4LL, UK.

Olaf L.F. Weyl Centre for Invasion Biology, South African Institute for Aquatic Biodiversity, Grahamstown, 6139, South Africa.

Catherine M. Yule Faculty of Science, Health, Education and Engineering, University of the Sunshine Coast, Locked Bag 4, Maroochydore DC, Queensland 4558, Australia.

Lauren Zielinski Zielinski Environmental Monitoring and Evaluation LLC, 6 Riverwalk, Hampton, NH 03842, USA & IHE Delft Institute for Water Education, Westvest 7, 2611 AX Delft, PO Box 3015, 2601 DA Delft, The Netherlands.