1

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

© Oxford University Press 2021

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Sorabji, Richard, author.

Title: Freedom of speech and expression : its history, its value, its good use, and its misuse / Richard Sorabji.

Description: New York, NY : Oxford University Press, 2021. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020037508 (print) | LCCN 2020037509 (ebook) | ISBN 9780197532157 (hardback) | ISBN 9780197532171 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: Freedom of speech. | Freedom of expression. | Social media.

Classification: LCC JC591.S 66 2021 (print) | LCC JC591 (ebook) | DDC 323.44/3— dc23

LC record available at https:// lccn.loc.gov/2020037508

LC ebook record available at https:// lccn.loc.gov/2020037509

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780197532157.001.0001 1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

Printed by Integrated Books International, United States of America

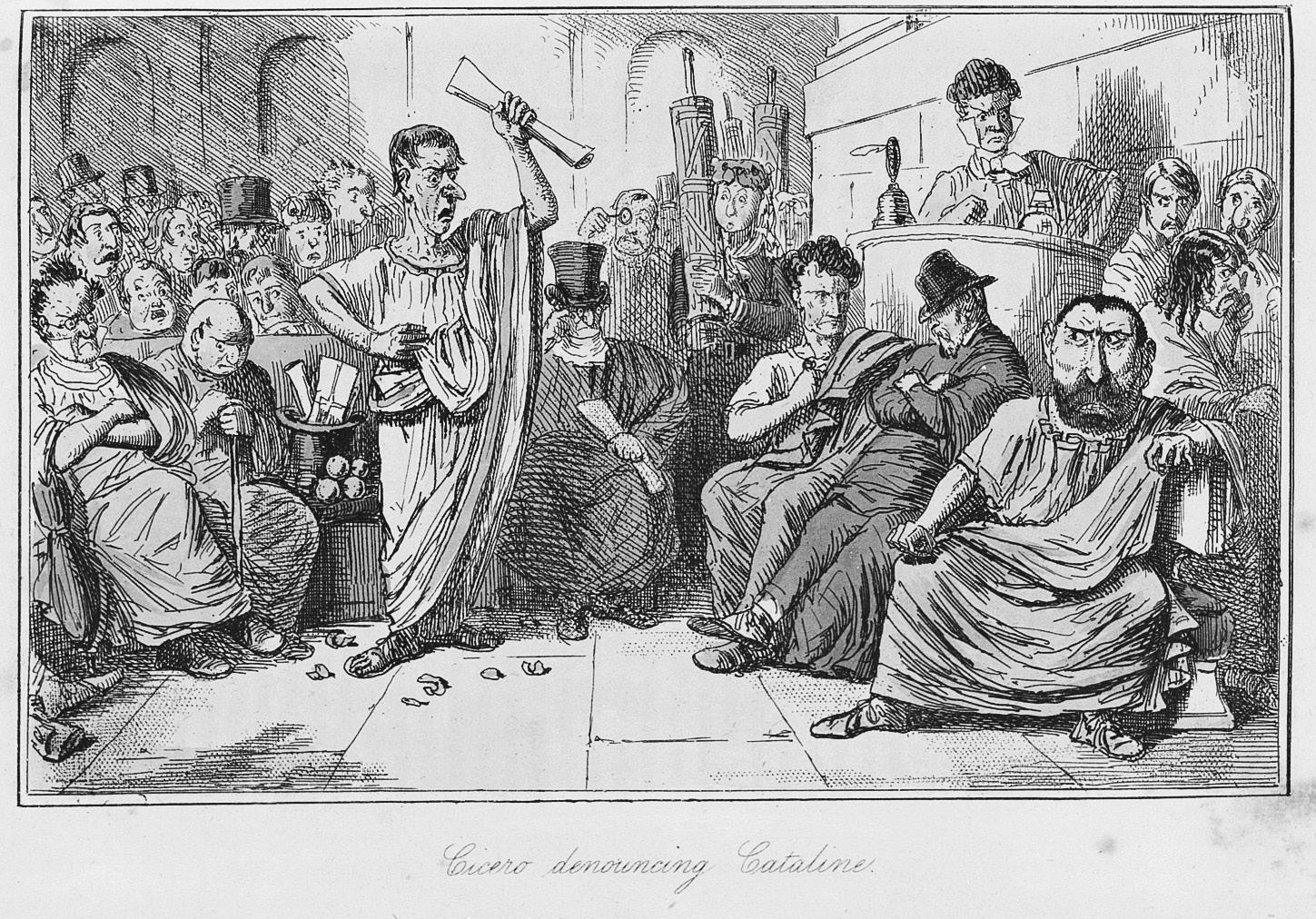

“Cicero denouncing Catiline” by John Leech. Courtesy of the Posner Memorial Collection, Special Collections, Carnegie Mellon University Libraries, Pittsburgh PA. From Gilbert Abbott A. Beckett and John Leech, The Comic History of Rome . London 1870: Bradbury, Evans & Co. (DG210 A12 1852A).

To Laila and Nadia

Series Editor Foreword ix

Acknowledgements xvii

Introduction xix

1. The benefits seen in free speech and its gradual extension from some to all: An intercultural history 1

2. The benefits of free speech and expression: Productive versus counter-productive speech, and voluntary boundaries 62

3. Free speech on social media: How to protect our freedoms from those social media that are funded by trade in our personal data 108

SERIES EDITOR FOREWORD

In 2014, I had the distinct privilege of being Chair of the Department of Philosophy at Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey. Soon after I become Chair, Peter Ohlin, philosophy editor of Oxford University Press, USA, broached the idea of Rutgers organizing a major annual lecture series, where Rutgers would carefully select among the world’s leading philosophers to give a series of three original lectures which would be subsequently revised for publication in a book series by Oxford University Press. It was Peter’s hope that such a series might soon come to be recognized as one of the most important annual events on the philosophical calendar, and might one day come to rival the Locke Lectures, Dewey Lectures, and Tanner Lectures in stature.

I shared Peter’s enthusiasm for the idea, and promised to take it up with my colleagues and our administration. Unsurprisingly, the response was overwhelmingly supportive. However, it was decided that if we were going to take on such a commitment, we wanted the endeavour to involve much more than just adding another three lectures, each year, to our already crowded academic calendar. We wanted to create a lecture series that was truly distinctive and special; one that would benefit not only our faculty, but our outstanding graduate students, undergraduates, and the wider Rutgers community. Moreover, we were especially concerned to create a lecture series that would be both personally and intellectually rewarding for our visiting speakers.

After much discussion, the Rutgers Lectures in Philosophy took shape. First, the Department was committed to bringing in genuinely world- class philosophers who had already done, and were continuing to do, seminal work that was profoundly impacting their areas of research and, in some cases, the world at large. Our hope, and expectation, was that the lectures they would be delivering at Rutgers, and the books based on those lectures, would help set the philosophical agendas in their respective fields for many years to come. Bearing that goal foremost in mind, we were also committed to inviting a diverse group of speakers, representing a broad spectrum of philosophical areas and interests within the analytic tradition.

Second, speakers would be asked to be available on campus for a full week, and to pitch their first lecture so that

interested alumni, the broader Rutgers academic community, and the general public might benefit from these internationally renowned philosophers. Their two subsequent lectures would be aimed at the high philosophical level that would most benefit the Philosophy faculty, graduate students, visitors, and speaker, and would likely form the backbone of the speaker’s subsequent book. Each lecture would be followed by discussion, a reception, and dinner, to facilitate serious engagement with the speaker’s views.

Third, speakers would distribute drafts of their lectures, which would be read and discussed in advance by interested faculty, graduate students, and visitors. Then, there would be an intensive workshop with the speaker on the distributed material during their week on campus, providing the speaker with valuable feedback, and the workshop members with the chance to get to know the speaker and his or her views in a seminar setting.

Fourth, there would be a separate lunch meeting with the speaker for interested undergraduate majors, minors, philosophy club members, and students working on the undergraduate philosophy journal, Arete . As it turns out, several speakers have reported their meeting with our undergraduates to be one of the biggest highlights of their visits!

Finally, speakers would be encouraged to hang around the Department for impromptu discussions, and to set up individual meetings with faculty or graduate students particularly interested in their work.

A little over two years after Peter Ohlin and I first spoke, the first Rutgers Lectures in Philosophy took place, and at this point the first four lectures in the Series have been delivered. The first book in the series, Kit Fine’s Vagueness: A Global Approach has been published, and now this, the second book in the series, will appear. It has been a long road between Peter Ohlin’s original idea and this moment, but we couldn’t be more pleased by how the lecture and book series have developed. It has truly been everything we envisaged it to be and more.

There are many people I would like to thank for helping to make the Rutgers Lectures in Philosophy possible. I apologize, in advance, for the fact that nothing I say here can remotely reflect the depth of my gratitude to those who have worked tirelessly behind the scenes to make this series a success. I also apologize to anyone I inadvertently forget to mention. On both scores, please forgive me.

First, my deep gratitude to Peter Ohlin, who not only planted the seed from which this lecture and book series has grown, but who has helped to nurture it and bring it to fruition at every step of the way. Peter’s contributions to this series have been both invaluable and indispensable. My thanks, also, to Peter’s excellent team at OUP, from the Editorial Board, to copyeditors, design artists, publicists, production managers, and so on, all of whom do yeomen’s work in bringing a book to press, and making sure that it receives the attention it deserves. Thanks, also, to Peter Momtchiloff, Oxford University Press’s philosophy editor in the United Kingdom, for sage advice in

this project’s initial stages. And a special thanks to the referees for the volumes in this series, whose conscientious work are almost always underappreciated by everyone but the authors.

In the Department of Philosophy, my biggest debt is to my colleagues, who were extremely supportive of this project from the get go, and who have spent countless hours deliberating about the Series format and possible speakers, and attending the numerous series events. I also want to thank all the graduate students who have actively participated in Series events, with a special thanks to Jimmy Goodrich and Adam Gibbons, who have done much of the heavy organizational lifting. I also owe a debt of gratitude to two business managers, Pauline Mitchell and Charlene Jones, our undergraduate administrative assistants, Jean Urteil and Jessica Koza, and, especially, our graduate administrative assistant, Mercedes Diaz, for all their hard work. Justin Kalef has organized the undergraduate luncheon meetings, and I am grateful to him, and all the undergraduates who have made that event a highlight of the lecture series. Special thanks is also owed to Dean Zimmerman, current Chair of the Rutgers Philosophy Department, for his crucial and unwavering support.

This series would never exist were it not for the substantial support that the Philosophy Department has received over many years from the Rutgers Administration, including Presidents, Chancellors, Vice-Presidents, and Deans. The Rutgers Lectures in Philosophy series thrives because of the incredibly vibrant and congenial philosophical environment that the Rutgers

Administration has made possible. I, and my colleagues, can’t thank them enough. I can’t possibly name every important administrator whose support has helped make the Rutgers Philosophy Department what it is today, but I need to mention a few: first and foremost, the current President, Robert Barchi. President Barchi is committed to excellence, and has been a great champion of our department. Following the President’s lead, Chancellor Richard Edwards and current Chancellor Christopher Malloy have both been enormously supportive.

A number of people in the Dean’s office have worked very hard, and successfully, to give the Rutgers Lectures in Philosophy Series a high profile not only within Rutgers, but globally. These include Kara Donaldson, who oversaw these efforts, Ian DeFalco, and John Chadwick. James Masschaele, Vice Dean of the School of Arts and Sciences, has been supportive from its onset, and Michelle Stephens has been supportive since becoming Dean of Humanities. Two people are deserving of special mention: James Swenson, former Dean of Humanities, and currently Vice Provost for Academic Affairs, and Peter March, Executive Dean of the School of Arts and Sciences. To each, my heartfelt thanks for all they have done over many years to support the Philosophy Department in general, and the Lecture Series in particular.

Finally, my biggest thanks go to the stars of the Series, the speakers whose path-breaking work is an inspiration to all those in the field. I am most grateful to those who helped put the series on the philosophical map, by agreeing to be one of our distinguished

speakers. As of now, the lineup of speakers is: Kit Fine (2016), Sir Richard Sorabji (2017), Robert Stalnaker (2018), Jeff McMahan (2019), Béatrice Longuenesse (2020), Tim Williamson (2021), Philip Kitcher (2022), and Susanna Siegel (2023).

Sir Richard Sorabji was and is everything we were seeking in a speaker. He presented entirely new work on a topic of fundamental importance socially, politically, and morally. Throughout his visit he was lively, modest, engaging, and accessible to all. And since his visit he has been both eager and diligent about revising and improving his book in a timely manner. He has truly been an exemplary scholar in every respect throughout this process, and an editor’s dream. The book you are now reading, Freedom of Speech and Expression: Its History, Its Value, Its Good Use, and Its Misuse , is certain to be a rich source of inspiration and discussion for years to come. I am extremely pleased to have Sir Richard’s book appear as the second book in the Rutgers Lectures in Philosophy Series. Those of us associated with the series have hoped that one day it would be widely recognized for its philosophical excellence. I have no doubt that Sir Richard’s book is another important step towards the realization of that hope.

Again, to everyone who has helped in bringing this book to press, and most especially Sir Richard Sorabji, my heartfelt gratitude.

Larry S. Temkin, Series Editor

New Brunswick, New Jersey

April 2020

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I was very pleased to be invited in 2016 by Professor Larry S. Temkin, on behalf of the Rutgers University Philosophy Department in partnership with the Oxford University Press, to deliver the 2017 Rutgers Lectures in Philosophy. The third Rutgers lecture has been replaced by a new chapter in order to address a major contemporary problem—social media.

I have benefitted from many discussions and written works, which I have tried to acknowledge in the main text. But here I should like to pick out two particular kinds of help.

The first was the highly valuable discussions during my week of lecturing at Rutgers University in October and November of 2017. The second was the detailed, closely considered, and clarifying comments obtained for me by Oxford University

Press, New York, on the penultimate draft of this book. One set was from my colleague in Oxford, Professor Jeff McMahan, who is himself the author of the 2019 lectures at the Rutgers Philosophy Department, his former base. The other was from Professor Han Baltussen at the Philosophy Department of the University of Adelaide, who led me to revise the structure of the book. I am grateful to Jane Potter for introducing me to the idea of citizen journalists.

I am grateful also to my friend and colleague Professor William Twining for giving me a jurisprudential view on chapter 3, and to the Oxford University Press editor in New York, Peter Ohlin, for very helpful comments on chapters 1 and 3. I also gained valuable comments, queries, and reading suggestions from an anonymous review commissioned by David Schmidtz, editor of Social Policy and Philosophy, in return for writing a version of chapter 3, without its appendix, for that journal. For me, writing good philosophy depends on such opportunities for discussion and comment.

Richard Sorabji

INTRODUCTION

I encountered the denial of free speech twice, once in my early days, when I was taught Russian by charming emigrés from Stalin’s Soviet Union, all of whom had terrifying tales to tell of unfreedom. I encountered it again, when I went behind the Iron Curtain to Prague in Czechoslovakia to talk about Aristotle’s Metaphysics with a group of academics, who had been sacked from the university and turned into window cleaners by a Soviet- dominated government so ignorant that it believed Aristotle’s Metaphysics might be politically dangerous. We met in private houses after working hours, could not speak each other’s names aloud, because the walls were bugged, and when my hosts wanted to continue discussion after midnight, they

Freedom of Speech and Expression. Richard Sorabji, Oxford University Press (2021). © Oxford University Press. DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780197532157.001.0001

could not come to my hotel for fear of incriminating the person who had separately booked me in, so we had to stand outside in the snow, in order to continue talking about Aristotle. I had to memorise, not write down, the titles of scholarly books they would like me to send them from England, and after the one member of the group still allowed to teach in Prague was also allowed to visit London University for three months of research, he committed suicide rather than return.

In 2012, I published a book on Mahatma Gandhi and the all-important philosophy of non-violence, compassion for opponents, and voluntary suffering, which led eventually to the end of British rule in India and I compared aspects of that philosophy with ancient Stoicism.1 I was particularly impressed by Gandhi’s conception of opening ears. He sought to open ears not by propaganda to the masses, but by nonviolent satyagraha: insistence on truth both to himself and to his powerful opponents, the British rulers of India. At least two British Viceroys felt some admiration for him, and eventually, he opened the ears of world opinion. These experiences of discussion and reading are part of what lay behind my interest in the subject of freedom of speech and expression, its history and its right use.

In this volume, chapter 1 points out that the idea of free speech for all became widespread comparatively late. On 1. Richard Sorabji, Gandhi and the Stoics , Modern Experiments on Ancient Values , Oxford University Press, Oxford, and the University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 2012.

the whole, it was treated as a prerogative of some people only, although an early exception was the Buddhist emperor Ashoka in India, who encouraged Buddhists of all persuasions to live and talk with each other and learn from each other, and people of different religions to do the same. Although it otherwise took a long time for free speech and expression to be extended to all, nonetheless, through different ages and cultures from antiquity to the present, the award of free speech, whether to some or to all, was seen as resulting in speech of a beneficial sort. That is why my title speaks of good speech and its misuse, rather than simply of speech and its misuse.

Chapter 2 argues that John Stuart Mill supported free speech on the grounds of the beneficial effects it can have, in Chapter 2 of his On Liberty of 1859. But the history in chapter 1 suggests that this has been a recurrent view through the ages. If free speech is valued for its benefits, speech that frustrates those benefits suggests a clear boundary on free speech which should appeal voluntarily to its supporters. Their voluntary self-restraint in speech should normally be better than legal constraint for keeping speech beneficial. But self-restraint is not the only preserver of benefits. Speech that opens ears, to take an expression of Gandhi’s, in his case the ears of powerful opponents, is also a preserver of benefits.

Chapter 3 turns to an important problem of our time. It says that law is after all required if we are to preserve our freedoms, when some of the online social media offset the benefits they have to offer by basing their profits on exploiting

personal profiles based on personal data left online by users. It spells out the bad effects of this and counters the suggestion that any media producing these bad effects can claim to be supporting free speech as understood by those reviewed in chapters 1 and 2. It supports the education of nine- to elevenyear- olds in detecting fake news and targeted news, and recommends encouraging compliant media. But with reference to Government documents, it also proposes new legislation and new methods of enforcement against such misuse of speech.

FREEDOM OF SPEECH AND EXPRESSION