https://ebookmass.com/product/framboids-david-rickard/

Instant digital products (PDF, ePub, MOBI) ready for you

Download now and discover formats that fit your needs...

https://ebookmass.com/product/framboids-david-rickard/

Instant digital products (PDF, ePub, MOBI) ready for you

Download now and discover formats that fit your needs...

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

© Oxford University Press 2021

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Rickard, David, 1943- author.

Title: Framboids / David Rickard.

Description: New York, NY : Oxford University Press, [2021] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020058329 (print) | LCCN 2020058330 (ebook) | ISBN 9780190080112 (hardback) | ISBN 9780197571927 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: Pyrites. | Ore deposits. | Sediments (Geology) | Texture (Crystallography) | Aggregation (Chemistry)

Classification: LCC QE390.2.I76 R525 2021 (print) | LCC QE390.2.I76 (ebook) | DDC 549/.32—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020058329

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020058330

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780190080112.001.0001

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

Printed by Integrated Books International, United States of America

For Simonne who has been there since the beginning

2.5.

2.4.3.

2.5.1.

2.6.

3.

3.1.

3.2.

3.1.1

3.1.2.

3.2.1.

3.4.

3.3.2.

4.

4.1.

4.5.

4.5.1.

4.5.2.

4.5.3.

4.5.4.

4.5.5.

4.5.6.

4.5.7.

5.

5.1.

5.2.

5.2.1.

5.2.2.

5.3.

5.3.1.

5.3.2.

5.4.

5.5.

6. The Crystallography of Pyrite Framboids

6.1. Pyrite Structure

6.2. Framboid X-ray Diffraction

6.3. Electron Backscatter Diffraction

6.3.1. Accuracy of Pyrite EBSD

6.3.2. Framboid Microcrystals Are Single Crystals

6.3.3. Microcrystal Orientations

6.4. Framboid Crystallography and Self-Organization

6.4.1. Origins of Different Crystallographic Orientations of Microcrystals in Framboids

7. Organic Matter in Framboids

7.1. Framboids as Fossilized Microorganisms

7.1.1. Schneiderhöhn’s Fossil Bacteria

7.1.2. Love’s Microfossils

7.1.3. Pyrite Precipitation within Prokaryotic Cells

7.1.4. Framboids as Fossil Microbial Colonies

7.1.5. Framboids as Fossil Giant Sulfur Bacteria

7.1.6. Framboids as Fossil Eukaryotic Microorganisms

7.1.7. Polyframboids as Steinkerns

7.2. Framboidal Organic Matter

7.2.1. Framboids and Biofilms

7.2.2. Geopolymers and Framboid Organic Matter

7.2.3. The Form of Protokerogen

7.2.4. Extrusion of Framboidal Organic Matter

7.2.5. Epigenetic Organic Matter

7.2.6. Composition of Infilling Materials within Framboids

7.3. Organic Matter in Framboids

8. Framboid Mineralogy

8.1. Non-pyritic Framboids

8.2. Sulfide Minerals, Other Than Pyrite, in Framboids

8.2.1. Marcasite Framboids

8.2.2. Greigite, Fe3S4, Framboids

8.2.3. Copper Sulfide Framboids

8.2.4. Sphalerite Framboids 161

8.3. Oxide Framboids 163

8.3.1. Magnetite Framboids 163

8.3.2. Iron and Mn (Oxyhydr)oxide Framboids 165

9. Geochemistry of Framboids 169

9.1. Pyrite Stoichiometry in Framboids

9.2. Pyrite Composition 173

9.2.1. Trace and Minor Elements in Sedimentary Pyrite

9.2.2. Trace Elements in Pyrite in Coal

9.2.3. Trace and Minor Elements in Hydrothermal Pyrite

9.3. Framboid Composition 179

9.3.1. Trace and Minor Element Compositions of Framboids 179

9.3.2. Trace Element Compositions of Hydrothermal Framboids 187

9.3.3. Sulfur Isotope Compositions of Framboids 187

9.4. Controls on the Trace Element Concentrations in Framboids 189

10. Pyrite Framboid Formation Chemistry

10.1. Pyrite Chemistry

10.1.1. Pyrite Solubility

10.1.2. Pyrite Formation Chemistry

10.2. The Polysulfide Reaction

10.2.1. Polysulfide Reactants

10.2.2. The Polysulfide Reaction Mechanism

10.2.3. Aqueous FeS as a Reactant

10.2.4. Protonated Iron Sulfide Complexes as Reactants

10.2.5. Aqueous Fe(II) as a Reactant

10.2.6. Iron Sulfide Minerals as Reactants 203

10.2.7. Nanoparticulate FeS

10.3. The H2S Reaction

10.3.1. The H2S Reaction Mechanism

10.3.2. Microbial Mediation

10.3.3. Iron (III) (oxyhydr)oxide

10.4. Pyrite Framboid Syntheses

10.4.1. Microframboids and Nanoframboids

10.4.2. Microspheres

10.4.3. Nanoparticulate Pyrite and Pyrite Clusters

10.5. Comparison of the Polysulfide and H2S Pathways for Framboid Formation

11. Nucleation of Framboids

11.1. Burst Nucleation: The LaMer Theory

11.2. Homogeneous and Heterogeneous Nucleation of Framboids

11.3. Classical Nucleation Theory

11.3.1. Critical Supersaturation

11.3.2. Surface Energy of Pyrite Nuclei

11.3.3. Pyrite Critical Nucleus Size

11.4. Framboid Size and Supersaturation

11.5. Nucleation of Framboids

11.5.1. Heterogeneous Nucleation of Pyrite

11.5.2. Nucleation of Pyrite Framboids

12. Framboid Microcrystal Growth

12.1. Origin of Pyrite Microcrystal Habits

12.1.1. Pyrite Surface Energies

12.1.2. Spectator Ions and Adsorption

12.2. Growth Mechanisms and Microcrystal Habit

12.2.1. Screw-Dislocation Growth

12.2.2. Surface Nucleation Growth

12.2.3. Crystallization by Particle Attachment (CPA)

12.2.4. Ostwald Ripening

12.2.5. Interrelationship between Monomer Attachment, CPA, and Ostwald Ripening

12.2.6. Supersaturation and Pyrite Framboid Microcrystal Growth Forms

12.3. Origin of Framboid Sizes and the Rate of Pyrite Framboid Formation

12.3.1. Crystal Size Distribution (CSD) Theory

12.3.2. Diffusion-Controlled Growth

12.3.3. The Rate of Pyrite Framboid Formation

12.3.4. The Rate of Polyframboid and Framboid Cluster Formation

12.4. Molecular Mechanism of Pyrite Crystal Growth

12.4.1. Effect of Temperature

12.4.2. Effect of pH

13. Framboid Self-Assembly and Self-Organization

13.1. Self-Assembly: The DVLO Theory

13.1.1. Hamaker Constant

13.1.2. Electrostatic Interactions

13.1.3. The Debye Length and Microcrystal Self-Assembly

13.1.4. Pyrite Surface Charge

13.1.5. Net DVLO Forces in Pyrite Framboid Self-Assembly

13.2. Self-Organization

13.2.1. Organic Templates

13.2.2. Spatial Constraints: Coacervates

13.2.3. Spatial Constraints: Sediment Pores

13.2.4. Topotactic Solid Phase Transformations

13.2.5. Compaction and Dewatering of Sediments

13.2.6. Microcrystal Alignment by Epitaxial Growth and Secondary Nucleation

13.3. The Self-Organization Process in Framboids

13.3.1. The Development of Framboid Shapes

13.3.2. The Development of the Framboid Microarchitecture

This book describes what framboids are and how they are formed. It is consequently divided essentially into two sections: Chapters 1–9 describe framboids and Chapters 10–13 discuss how they are formed. This synopsis integrates the two parts into an integral whole which acts as a vade mecum for the volume. Section links are listed in parentheses.

Generally, framboids are ubiquitous microscopic, sub-spherical aggregates of often, geometrically arranged, pyrite microcrystals. The basic attributes of framboids are their microscopic size, their sub-spheroidal form, and their microcrystalline internal structure (1.1).

Framboids are predominantly made of pyrite. This is due to the chemical properties of this mineral and its crystallography, as well as the relative natural abundances of iron and sulfide. The extreme dominance of pyrite means that term framboid generally refers to pyrite framboids unless otherwise qualified.

The question of whether other minerals form framboids directly is moot (8.2). Detailed examination of reports of other mineral framboids reveal microcrystalline material within and associated with framboids (e.g., greigite, Fe3S4g) and subspherical crystalline aggregates (e.g., marcasite, chalcocite-digenite, magnetite). In contrast, framboidal aggregates of, for example, polystyrene microspheres, have been widely synthesized, so there is no a priori reason for other minerals not forming primary framboids. The limitation is probably the requirements of crystal habit, solubility, and natural abundances of the constituent elements for framboid formation.

Framboids are sometimes observed replaced by other minerals. Pyrite framboids are often formed during the earliest stages of sedimentation or mineralization and therefore subject to further reactions with later fluids. Minerals such as copper, cobalt, zinc, and lead sulfides often display framboidal forms having replaced original pyrite framboids (8.2.3, 8.2.4). Likewise, oxidation of

pyrite under some conditions can produce iron oxyhydroxide and iron sulfate framboids (8.3).

Framboids may be the most abundant mineral texture on Earth. There are around 1030 framboids on Earth, and they are forming at a rate of about 1021 per year or 1014 per second (1.2.1). They are found throughout the geologic record; the oldest framboid may be 2.9 Ga. They are abundant in rocks less than 600 Ma old, and decrease through the Proterozoic (>0.6 Ga) until they are rare in Archean rocks (>2.5 Ga) (1.3.2). Their absence in these ancient rocks may be related to the low concentrations of sulfate in contemporary seawater, and there is some suggestion that they tended to occur in systems where sulfate was locally enriched, such as through hydrothermal activity. They are far more abundant in sediments and sedimentary rocks than in hydrothermal deposits, and their presence in igneous rocks appears to be limited to hydrothermal veinlets within volcanic rocks (1.3.4).

Historically, framboids have been known since at least 1885 and were defined in 1935 (1.2). Early interpretations suggested that they were fossilized microorganisms, and in the 1950s this idea was resurrected by the discovery of organic matter in some framboids (7.1). The pyrite-sulfur in sedimentary framboids is almost wholly sourced through the activities of sulfate-reducing microorganisms, so there is a direct relationship between sedimentary framboids and microorganisms (see p. 129). Subsequently, the limited distribution of organic matter in framboids, its absence in hydrothermal framboids, and inorganic framboid syntheses showed that organisms were not necessary for framboid formation.

One of the basic attributes of framboids is their microscopic size. Framboid sizefrequency distributions are log-normal; the geometric mean size of framboids is 6.0 μm and 95% of framboids range in size between 2.9 and 12.3 μm in diameter (2.3). The largest framboids may be 250 μm in diameter, although spherical aggregates of framboids, known as polyframboids, may range up to

900 μm in diameter (2.7). Various spherical aggregates of nanoparticles have been described which are less than 0.2 μm in diameter. These do not form a continuum with framboids (2.1.1).

There is no evidence for any significant change in framboid diameters with geologic time (2.4.1), and the differences in mean sizes between hydrothermal and sedimentary framboids do not, at present, appear to be statistically significant (2.6). By contrast, it appears that the mean diameters of framboids from non-marine sediments are significantly larger (7.6 μm) than marine framboids (5.7 μm) (2.4.3). There is some evidence that framboids formed in the water column are smaller than those formed in sediments, but the non-critical use of this possible difference as a proxy for paleoenvironmental reconstructions is not robust (2.5.1).

Framboids are constituted by microcrystals. Microcrystal size distributions are approximately log-normal and 95% of framboidal microcrystals are between 0.1 and 3.1 μm (4.1). Packing efficiencies range from cubic and hexagonal close packings (74 vol %) to random packings (56–64 vol %) (4.2.1).

Framboids contain between less than 100 to over 500,000 microcrystals (4.2). The ratios of framboid diameters to microcrystal sizes show a clear bimodal distribution which reflects the populations of close packed ordered framboids and close packed randomly organized framboids (4.2). The average numbers of microcrystals in both disordered and ordered framboids are similar, which suggest that the organization of microcrystals is the result of an additional process.

Minerals that do not commonly produce equant crystals forms are unlikely to display the framboidal texture. This essentially limits the framboid texture to minerals, like pyrite, displaying isometric symmetry (4.4). The permutations of pyrite habits result in pyrite displaying the greatest variety of crystal shapes among the common minerals, which includes approximations to forbidden fivefold symmetries such as the pyritohedron and pseudo-icosahedron.

The original idea that framboids were generally spherical was found to be due to the limitations of the contemporary optical microscopic methods (1.2.2). Later scanning microscopic investigations showed that many framboids were at least partly faceted and some display polygonal icosahedral forms (3.3). This is significant since the assumption of framboid sphericity informed earlier explanations of how they could form. It cannot be assumed that framboids necessarily require a precursor template, such as a spherical space or spherical organic globule, to develop.

Framboids were originally studied in sections, and this is still a common method of investigation (5.1.1). Sections through framboids reveal that the microcrystals in pyrite framboids often show extremely regular arrangements. Framboids can be classified in terms of whether their constituent microcrystals are regularly arranged (ordered in a single domain), randomly arranged (disordered), or mixtures of both (partially ordered or multiple domains) (5.1.1). The relative proportions of these three types are unknown, but there may be a tendency for the proportion of ordered framboids to increase with geologic age.

Framboids are not mesocrystals or extreme skeletal varieties of single crystals, and single crystal X-ray diffraction analyses of even the most perfectly organized framboids show ring patterns indicative of dominantly randomly oriented particles (6.2). Further detailed studies of microcrystal crystallinity by electron backscatter diffraction showed that the microcrystals within a framboid are not crystallographically aligned (6.3.3). Both randomly packed and organized framboids show adjacent framboids with crystallographic orientations rotated 90º. Framboids are formed by the aggregation of pyrite microcrystals rather than the sequential growth of one microcrystal on another.

The fundamental driving for the self-assembly of framboid microcrystals is reduction in surface free-energy (13.1). The self-assembly of framboid

microcrystals to form framboids is consistent with estimations based on the classical Derjaguin-Landau-Verwey-Overbeek (DVLO) theory, which balances the attraction between particles due to van der Waals forces against the interparticle electrostatic repulsive force (13.1).

Maximization of entropy is the fundamental process leading to the development of regular arrangements of microcrystals in framboids (13.3). The formation of framboids involves two distinct processes. First, pyrite microcrystals aggregate into sub-spherical groups through free energy minimization. Second, the microcrystals rearrange themselves into ordered domains through entropy maximization. Icosahedral symmetry tends to minimize short-range attractive interactions and maximize entropy (13.3.2). The physical processes that facilitate this rearrangement are Brownian motion and surface interactions.

The formation of many thousands of equidimensional and equimorphic microcrystals in framboids is the fundamental evidence for burst nucleation (11.1). This is conventionally described by the LaMer model, which is characterized by (1) a lag phase before nucleation becomes significant, (2) burst nucleation where the rate of nucleation increases exponentially and may be completed in seconds, and (3) a short growth phase where nucleation becomes again insignificant (11.1). The growth phase is dominated by crystal growth, which is limited by the supply of nutrients, which is not replenished, and growth is rapidly extinguished. The result of LaMer kinetics is a large number of similarly shaped colloidal particles.

The extreme insolubility of pyrite is one of the fundamental reasons for its particular involvement in framboid formation, as well as for the ubiquity of framboids (10.1.1). Pyrite solubility is determined by the activities of Fe(II) and S2(-II). Aqueous Fe2+ does not appear to react directly with aqueous polysulfide species to produce pyrite, and the S-S bond in aqueous S2(-II) is normally split by aqueous Fe2+ to produce aqueous FeS and sulfur (10.2.5). The mechanisms of pyrite formation include the polysulfide pathway and the H2S pathway. FeS is the reactant moiety in both processes, either as a dissolved aqueous cluster or a

surface-bound species. The polysulfide pathway involves the substitution reaction between aqueous S2(-II) and FeS with [FeS.HS2]– as the reaction intermediate (10.2.2). The H2S pathway involves the redox reaction between H2S and FeS (10.3.1). Both are involved in pyrite nucleation from aqueous solution and pyrite crystal growth, and both processes have been proven by isotopic tracing. Both processes have been shown to produce framboids.

The supersaturation required for pyrite to nucleate is conveniently defined in terms of the critical supersaturation which defines a point at which nuclei begin to form at a measurable rate (11.3.1). The critical supersaturation is related to the solubility via the surface energy. The computed critical saturation for pyrite varies between 1011 and 1018, which is consistent with experimental estimates.

The formation of pyrite nuclei is extremely sensitive to the surface energies of pyrite nuclei, and small changes in supersaturation lead to changes in the rate of nuclei formation of several magnitudes. Assuming that the initiation of burst nucleation can be approximated to a rate of one nucleus per second, CNT suggests a mean surface energy of around 0.6 J m–2 for pyrite nuclei in aqueous solution at standard ambient temperature and pressure (SATP) (11.3). The critical radius for pyrite nuclei under these conditions is between 2.3 and 3.8 Å, which is similar to the dimensions of the pyrite unit cell (11.3.3).

By contrast with framboids, euhedral pyrite crystals evidence the formation of isolated nuclei (11.5.1). These isolated nuclei continue to grow in regimes where the nutrient supply is not depleted or restricted, resulting in the formation of euhedral pyrite crystals.

Iron (oxyhydr)oxides are the major source of reactant Fe in sedimentary environments. The reaction between aqueous S(-II) and Fe(III) (oxyhydr)oxides produces surface =FeS, polysulfides and surface disulfide. The resulting formation of surface FeS2 moieties through the reaction between surface =FeS and S2(-II) leads to the heterogeneous nucleation of pyrite (11.5.1). This reaction may the major route for producing individual pyrite crystals, rather than framboids,

especially in sediments. The reaction with surface =FeS is, of course, not limited to iron (oxyhydr)oxides, but occurs with any iron mineral in a sulfidic environment, including the relatively scarce iron sulfides mackinawite and greigite, as well as pyrite itself. The reaction with surface =FeS sites on pyrite is a major route for euhedral pyrite crystal growth (12.4).

One of the major consequences of the relative insolubility of pyrite is the huge supersaturations with respect to pyrite that occur widely in low oxygen environments. The result is that the initial stage of pyrite microcrystal growth occurs in solutions with large supersaturations, and the less stable octahedral faces develop first (12.2.5). As the pyrite crystals grow, the solution becomes depleted in nutrients and the supersaturation begins to approach saturation and the most stable—or least soluble—cube faces develop. Truncated cubes and octahedra are thus common microcrystal habits.

The three basic processes in crystal growth in framboids—monomer addition, crystallization by particle attachment (CPA), and Ostwald ripening—are neither necessarily successive nor exclusive (12.2.4). End member monomer growth produces more extreme monodispersed populations of microcrystals. By contrast, CPA appears to result in quite irregular microcrystals which naturally lead to more disorganized geometries.

The rate of pyrite crystal growth is unknown. Various qualitative observations suggest that pyrite crystal growth is rapid and diffusion-limited. Since pyrite solubility is so low, diffusion-controlled growth can be closely modeled by linear approximations to the diffusion equations (12.3.3). These show that framboids take between a few hours to a few years to form. The average framboid takes 3–5 days to form whereas, because of the exponential nature of the relationship between framboid size and time, there is not much difference in the time taken for 80 μm (2.2 years) and the maximum observed 250 μm (3 years) diameter framboids to form.

The effect of temperature on the rate of framboid formation is not well constrained. As a first approximation, it appears that rate of framboid formation

is over a magnitude faster in hydrothermal systems than in sedimentary environments under similar monomer concentrations. In practical terms this means that an average 6 μm framboid forms in around 12 hours in hydrothermal systems rather than 3–5 days in sediments.

Pyrite forms mainly through two routes: (1) the reaction between FeS species and polysulfides (10.2), and (2) the reaction of FeS species and H2S (10.3). Both of these reactions produce framboidal pyrite. Although pyrite displays extreme stability in terms of pH space, variations in pH affect the rate of framboid formation through the effect of pH on the solubility of FeSs, which limits the potential maximum concentration of dissolved Fe(II) and S(-II) in solution (12.4.2). At pH <7 the solubility of FeSs is a function of the square of the proton concentration and thus its solubility increases rapidly with decreasing pH (10.2.5). Framboid formation is further constrained by pH since solutions with pH <5 produce marcasite rather than pyrite (8.2.1, 12.4.2). H2S is the dominant dissolved sulfide species at pH <7, so the H2S reaction is mainly limited to between pH 5 and 7. The dominant polysulfide species between pH 4 and 11 is HS2– and this would seem likely to be the major polysulfide reactant.

There is an intrinsic association between organic matter and sedimentary framboids since the sulfide in sedimentary pyrite is almost wholly the result of microbial sulfate reduction by mainly heterotrophic organisms (7.2). The exact nature of this organic material is unknown. However, it appears that microbial biofilm may be an important contributor (7.2.1). Likewise, the organic residues from framboids often appear similar to sulfur-rich organic geopolymers such as protokerogen (7.2.2). Most of the organic matter in framboids appears to be syngenetic with the framboids, and framboids seem to have grown in organic substrates.

The organic relicts tend to take on the form of the pyrite rather than vice versa (7.1.2). If organisms are involved as templates for framboid formation, they have not as yet been defined. Generally, known prokaryotic cells, such as giant sulfur bacteria, are too delicate to provide a scaffold for pyrite framboid formation (7.1.5). Eukaryotic organisms which might provide an internal template for framboid formation have not as yet been identified.

At present, the composition of pyrite in framboids is unknown, although it would be interesting to know its stoichiometry (9.1). The trace element content of framboids has been widely reported since framboids usually constitute the earliest pyrite phase in a sediment and therefore are more likely to pick up trace element variations in contemporary seawater (9.3.1). However, the processes leading to trace element contents of framboids are complex and poorly understood.

No spatial variations in δ34S compositions have been reported within individual framboids (9.3.3). This is consistent with the process of burst nucleation in framboids. It does suggest that framboids pick up a more accurate measure of the sulfur isotopic composition of the prevailing dissolved sulfide and the trace element composition of the contemporary environment and are likely to retain these over geologic time.

The pillars on which this monograph is constructed are three dissertations: my original undergraduate dissertation in 1965 and the PhD theses of my students

Ian Butler (1994) and Hiroaki Ohfuji (2004). I thank Ian Butler and Hiroaki Ohfuji for allowing me to reproduce many of the images from their theses. They also reviewed many of the chapters and were involved in developing many of the ideas recounted in this book.

This monograph is multidisciplinary and could not have been completed without the dedicated work of a large number of reviewers. First and foremost was Rob Raiswell, Emeritus Professor of Sedimentary Geochemistry at Leeds University, United Kingdom, who read and commented on all 13 chapters. He also made a series of constructive comments on the structure of the volume based on his overview.

I thank the following colleagues who reviewed one or more chapters of the book and whose time and effort in helping to see the work on framboids published underlines the importance of the topic to a variety of research disciplines.

Ian Butler

Michael Engel

Daniel Gregory

Stephen Grimes

University of Edinburgh

Friedrich-Alexander-Universität

Erlangen-Nürnberg

University of Toronto

Plymouth University

Miguel Angel Huerta-Diaz Universidad Autónoma de Baja California

Ross Large University of Tasmania

George Luther University of Delaware

Hiroaki Ohfuji

Rob Raiswell

Kevin Rosso

Zbigniew Sawłowicz

Nicolas Tribovillard

Tohuko University

University of Leeds

Pacific Northwest National Laboratory

Jagiellonian University, Krakow

Université de Lille

A number of distinguished researchers also made comments on specific areas of the book and helped in clarifying particular areas.

David Bond University of Hull

Julia Dshemuchadse University of Michigan

Robert Finkelman University of Texas, Dallas

Dimo Kashchiev University of Sofia

Danlil Kitchaev University of California, Berkeley

Paul Midgley University of Cambridge

Raúl Merino Palomeres University of Madrid

Juergen Schieber

Indiana University

Werner Stahel ETH, Zurich

Gregor Trefalt University of Geneva

Richard Wilkin

United States Environmental Protection Agency

The subject of framboids cannot be described without the inclusion of many images and, over the years, many colleagues have sent me images of framboids they have discovered or synthesized. Many of these images are included in this monograph and it could not have been completed without these contributions.

Robert Berner † Yale University

Ian Butler University of Edinburgh

Anders Elverhøi Oslo University

Stephen Grimes Plymouth University

Mizela Lay University of Tasmania

George Luther University of Delaware

Peter McGoldrick University of Tasmania

David H. McNeil

Geological Survey of Canada

Christopher Morrissey † Hagley, Worcestershire

Indrani Mukherjee University of Tasmania

Edward B. Nuhfer Niwot, Colorado.

Hiroaki Ohfuji University of Tohoku

Heikki Papunen University of Helsinki

Matías Reolid Perez University of Jaén

Zbigniew Sawłowicz Jagiellonian University, Krakow

Heide Schulz-Vogt Leibniz-Institut für Ostseeforschung, Rostock

Nicolas Tribovillard University of Lille

Laura A. Vietti University of Wyoming

David Wacey University of Western Australia

Many colleagues, in addition to the ones listed in the previous paragraphs, have been involved in discussions about framboids during the last 55 years, and these have helped mold the present volume.

G. Christian Amstutz† Heidelberg University

Hubert Barnes Pennsylvania State University

Dan Bubela† Baas Becking Geomicrobiological Institute, Canberra

Jacques Jedwab † University of Liege

George Kato Kyushu University

Leonard G. Love † University of Sheffield

Anthony P. Millman † Imperial College, London

John Morse† Texas A&M University

Marjorie D. Muir

Imperial College, London

Anthony Oldroyd Cardiff University

Richard A. Read Imperial College, London

The list is not complete, and I apologize to those colleagues I have inadvertently missed.

The monograph lists 469 references, often from ancient and esoteric sources. I thank Jacqueline Roach of the interlibrary loan team of Cardiff University for her dedicated assistance in sourcing many of these publications.

Finally, I thank my commissioning editor at Oxford University Press, Jeremy Lewis, for his unflagging support and encouragement.

Framboids are defined as:

Microscopic spheroidal to sub-spheroidal clusters of equant and equidimensional microcrystals.

The characteristics of the framboid texture need to be carefully defined since it is apparent that there are a large number of textures reported in the literature which are confused with it. This often refers to the more esoteric reports of framboids. For example, Garcia-Guinea et al. (1997) described large pyrite spheres in the remains of ink in the seams of 16th- and 17th-century books, which they described as framboids. In fact, these were smooth spherules of pyrite with no internal microcrystalline structure.

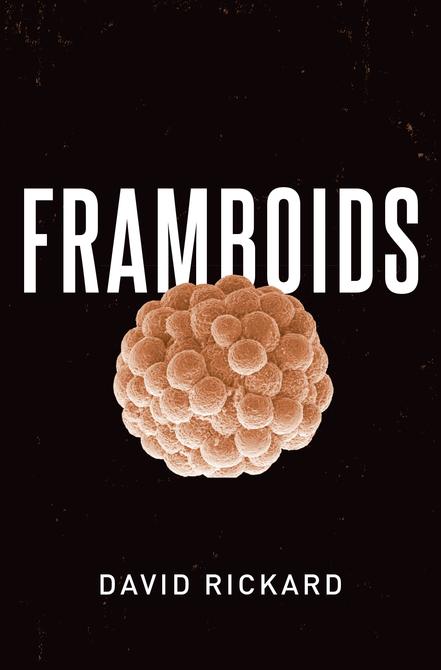

The key attributes of framboids are the microscopic size, the spheroidal to subspheroidal outer form, and the internal microcrystalline structure (Figure 1.1). It is these attributes which have made framboids so interesting to mineralogists, geologists, and geobiologists, as well as materials scientists. A particularly astonishing feature is the self-organization displayed by some pyrite framboids. However, the degree of self-organization is highly variable, and most framboids display only limited or even no obvious internal organization.

Pyrite framboids found in nature range from <1 to 250 µm in diameter and display a mean size of around 6 µm. This means that the number of average-sized framboids that can be placed on the period at the end of this sentence is 1850. The aggregates are made up of pyrite microcrystals, rarely more than 500 nm across, which sometimes display extraordinary ordering. The number of these microcrystals in any single framboid ranges between 102 and 107 (<0.1 ~20 µm in diameter). So probably more than 2 billion framboid microcrystals can be placed on a period. The point is that framboids are exceedingly small and not usually visible to the naked eye: they occur all around us without our being aware of them.

Framboids. David Rickard, Oxford University Press. © Oxford University Press 2021. DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780190080112.003.0001