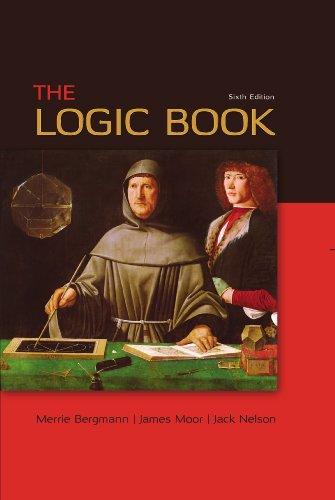

Facilitating Injustice

The Complicity of Social Workers in the Forced Removal and Incarceration of Japanese Americans, 1941–1946

YOOSUN PARK

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

© Oxford University Press 2020

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Park, Yoosun, author.

Title: Facilitating injustice : the complicity of social workers in the forced removal and incarceration of Japanese Americans, 1941–1946 / Yoosun Park.

Description: New York, NY : Oxford University Press, [2019] | Includes bibliographical references. | Summary: “Social work equivocated. While it did not fully endorse mass removal and incarceration, neither did it protest, oppose, or explicitly critique government actions. The past should not be judged by today’s standards; the actions and motivations described here occurred in a period rife with fear and propaganda. Undergoing a major shift from its private charity roots into its public sector future, social work bounded with the rest of society into “a patriotic fervor” (Specht & Courtney, 1994, p.ix). The history presented here is all the more disturbing, however, because it is that of social workers doing what seemed to them to be more or less right and good. While policies of a government at war, intractable bureaucratic structures, tangled political alliances, and complex professional obligations, all may have mandated compliance, it is, nevertheless, difficult to deny that social work and social workers were also willing participants in the events, informed about and aware of the implications of that compliance. In social work’s unwillingness to take a resolute stand against the removal and incarceration, the well-intentioned profession, doing its conscious best to do good, enforced the existing social order and did its level best to keep the Nikkei from disrupting it. What might social work in the camps have looked like, had it, instead of urging caution to deflect attention to its work, instead of denying that its work was coddling the Nikkei, have attempted, at the very least, to challenge the very logic that made—and continues to make—assisting the needy and caring for the vulnerable, actions to be mistrusted, defended, and justified? What lessons can today’s social work glean from this history?”— Provided by publisher.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019020540 | ISBN 9780199765058 (hardback) | ISBN 9780190081355 (epub) | ISBN 9780190081348 (updf)

Subjects: LCSH: Japanese Americans—Evacuation and relocation, 1942–1945. | Social service—Moral and ethical aspects—United States—History—20th century. | Social work administration—Moral and ethical aspects—United States—History—20th century. | United States—Race relations—History—20th century.

Classification: LCC D769.8.A6 P37 2019 | DDC 940.53089/956073—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019020540

Printed by Integrated Books International, United States of America

To beloved teacher, mentor, and irreplaceable friend, Professor Hideki Anthony Ishisaka, born in Amache.

Preface

An Occluded History

In 1943, Edward J. Ennis, director of the U.S. Justice Department’s Alien Enemy Control Unit, addressed the Seventieth National Conference of Social Work on the issue of enemy aliens in that wartime period. He explained that “within twenty-four hours after the attack on Pearl Harbor 1,000 Japanese aliens had been apprehended, and within a week a total of 3,000 alien enemies of German, Italian, and Japanese nationality were in the custody of the Immigration and Naturalization Service” (1943, p. 291). This initial apprehension of individual aliens was inaugurated in early December 1941. Within three months, the decision was made for the forced removal and incarceration of an entire population. On February 19, 1942, President Franklin Roosevelt issued executive order 9066 (3CFR1092-93), instituting “the greatest planned and controlled migration in our history: the movement of the American Japanese” (Powell, 1943, p. 301). From the last days of February 1942, when the Nikkei residents of Terminal Island became the first group forced from their homes, to March of 1946, when the last of the Relocation Camps was finally closed, the federal government incarcerated approximately 120,000 persons of Japanese ancestry (Burton, Farrell, Lord, & Lord, 2000; Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians, 1982; War Relocation Authority, 1946). Two-thirds of those interned were U.S.-born citizens. The rest were aliens, first-generation Japanese immigrants who, by the provisions of the 1790 Naturalization Act (1 Stat.103) which limited naturalization rights to “free whites,” could not become citizens. No other population, alien or citizen, who traced their ancestry to an enemy nation was subjected to wholesale removal and incarceration. “According to the War Relocation Authority, it had, at one time or another, 120,313 individuals in custody. It received 111,236 from the Army, 1,118 from Hawaii, 1,735 who were transferred from INS internment camps, 219 ‘voluntary residents’ (mostly individuals who joined families already in camp), and 24 from various institutions. In addition, 5,981 U.S. citizens were born to incarcerated mothers” (Daniels, Kitano, & Taylor, 1986, p. 73).

Social workers were involved in every part of the process; they were integral cogs in the total engine of forced removal and incarceration. Representatives of

West Coast branches of the American Association of Social Workers (AASW) testified at congressional hearings held on the impending mass removal of the Nikkei (United States Congress—House Select Committee Investigating National Defense Migration, 1942a, 1942b, 1942c). State and county social workers vetted, registered, counseled, and tagged all Nikkei individuals, along with their accompanying luggage, at the many Wartime Civil Control Administration (WCCA) stations, the first stop on the forced removal to mass incarceration (Leahy, 1945, p. 35; Nickel, 1942a). Social workers staffed administrative offices within the War Relocation Authority (WRA) concentration camps in which the Nikkei were imprisoned (Freed, 1944; Gottfried, 1944; Leahy, 1945; Nickel, 1943; Webb, 1946). They worked in the Washington headquarters of the WRA and in the regional offices through which it conducted its “resettlement” program, a planned scattering of the population explicitly intended to prevent their regional concentration (Leahy, 1945).

The history of social work presented in this study is offered as an exemplar for the examination of an enduring tension within social work which often pits its functions in conflict with its purported values and ethics: the profession’s dual role as deliverer of social policies and defender of those affected by them. In its unwillingness to take a resolute stand against the removal and incarceration of the Nikkei and in carrying out its “willingly accepted” (DeWitt, 1943, p. 1) government-assigned tasks, social work enacted and thus legitimized the bigoted policies of racial profiling en masse. The profession’s contradictory role—facilitating unjust government policies and actualizing social biases while striving to ameliorate their consequences—is, however, not a phenomenon unique to this event or even the past but a recurring and current problematic visible in contemporary social work. Indeed, while the setting for the events chronicled here is a nation at war more than half a century past, the ideas and ideals that fueled and enabled the events—the intersecting discourses of race, racism, culture, and the borders of legal and social citizenship—are all too familiar today. This analysis of the choices made and enacted by the profession and its professionals of that nation in crisis can help to illuminate the necessary task of examining the profession’s current approaches, practices, and policies within this troubled nation.

Acknowledgments

This project, many years in the making, would not have been possible without the labor of many. My heartfelt thanks go to research assistants Alex Kim, Andrea Yoshida, and Alicia Simoni who provided invaluable aid in and outside of the archives. Particular thanks are due also to Shea Henly who arrived like a gift from the universe to not only help me through the final tasks necessary to finishing the book, but also turned a much needed pair of keen eyes to read the text through in its entirety. I am ever grateful to Dr. Susan P. Kemp, for nudging me towards history during my doctoral studies, and to Dr. Joshua Miller provided useful feedback on an earlier version of this text. Thanks also goes to the Columbia University Population Research Center where I spent a productive year as a Visiting Scholar, researching and writing parts of this book. Funding from the Lois and Samuel Silberman Fund Faculty Grant Program and the Smith College Brown Foundation Clinical Research Institute made the project possible; both are gratefully acknowledged. Finally, eternal love and appreciation are due to my family: Dr. Andrew G. Rundle, Christopher B. Park, Alexander P. Park, and Sophia B. Rundle, whose love and support propelled me through many crises of confidence, conviction, and will.

Introduction

During my dissertation research into the representation of immigrants in social work discourse in the early years of the profession, I came across a startling article in the pages of Social Service Review about the involvement of social workers in the ignominious history detailed in the following chapters. No history of the profession I had ever read had mentioned the disconcerting fact that social workers were involved in all aspects of this history, and, while my subsequent search in the stacks uncovered a handful of articles on the topic written during the war years, I also discovered that none had been written since. Not one of my fellow students knew about the role social workers played in this history. Only one of the many professors I encountered during my studies did; he had been born in a War Relocation Authority (WRA) camp usually called Amache, officially known as Granada. It seemed that social work and social workers’ involvement had been forgotten altogether.

Lack of historical knowledge is, of course, in no way idiosyncratic to social workers. The Marxist historian Eric Hobsbawm once wrote that “no one who has been asked by an intelligent American student whether the phrase ‘Second World War’ meant that there had been a ‘First World War’ is unaware that knowledge of even the basic facts of the century cannot be taken for granted” (1994, p. 3).1 But the poverty of knowledge about its own past actions seemed especially troubling for this profession and discipline which prides itself on its dedication to social change and the amelioration of social ills for the benefit of those at its margins. How were we to honestly evaluate our present actions and formulate future plans if we did not even know that our “public past” (1994, p. 3) had included such complicity in injustice?

As I learned in the subsequent years of study, the involvement of social workers had not only been forgotten by social work, but it had never been studied by scholars of the history. The study presented here is an effort to address the lacuna in social work history. As the WRA commented in an internal document circulated at the time of resettlement, the “full story behind the West Coast evacuation has never been adequately told and probably will not be until many years after the return to peace. It is a complex story with many chapters that must necessarily remain hazy in time of total war” (War Relocation Authority, 1942, p. 5).

1 See Park (2006).

The chapters presented here are the tentative first attempts at reconstructing that complex and nearly forgotten history. The facts of the larger history of the forced removal and mass incarceration are well-documented; the body of scholarship and personal accountings and analyses of the events and their aftermath are extensive and far too numerous to list here. I have made no effort to recover those well-established grounds.2 The narrative arc I have constructed here traces the presence of social work and social workers in the history to establish what social workers did and how they did so. What this means, in concrete terms, is that this particular accounting does not always follow the major event markers usually highlighted in analyses of the larger history of removal and incarceration. Many important facts and events are omitted wholesale or glossed over without detailed explanation. There is no discussion, for example, of the removal and incarceration of the Latin American Nikkei. Major ventures such as the student relocation program, group resettlement to Seabrook Farms, and significant events such as the Manzanar revolt and the Poston strike, have been left out of the discussion. My sole focus was on reconstructing the path of social work through the events and processes of removal, incarceration, and resettlement, though inevitably, even that history is incomplete. Many facets of social work’s wartime work—for example, its involvement in the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) Detention Stations, Department of Justice Internment facilities, and U.S. Army internment facilities where individually arrested Issei and some family members were detained—have not been examined for this study. Much work remains to be done.

Notes on Terminology

Euphemisms abound in this history.3 “Evacuation” was the official terminology for the forced removal of an entire racialized civilian population and “relocation” the term for their mass incarceration by the federal government. In all cases, the choice of terminology is a political decision. Should the outbreak of violence which occurred in December 1942 at Manzanar be properly called a riot or an uprising? The choice colors the ways in which the killing of two inmates by soldiers firing into the crowd and the subsequent imposition of martial law can and should be interpreted. The choice of terminology for the population in question, ranging

2 An excellent resource for those wishing for more information on various aspects of the history is Densho, “a free on-line resource about the history of the Japanese American WWII exclusion and incarceration experience” (https://encyclopedia.densho.org/).

3 See the Power of words handbook (2013), by the National Japanese American Citizens League (https://jacl.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/Power-of-Words-Rev.-Term.-Handbook. pdf).

from “Japanese Americans,” which the most progressive tended to use; to the shorthand “Japanese,” which rendered both the citizen Nisei and the immigrant Issei equally alien; to the pithy expletive “Jap” used by far too many in the history, shapes the ways in which the removal, incarceration, and the planned scattering of the population post-imprisonment can and should be understood.

The Population

“Evacuees” and “center residents” were the terms most often used by officialdom to describe the displaced and incarcerated. The Issei, the first-generation immigrants from Japan, were also often identified as “Japanese aliens” (see, e.g., Ennis, 1943, p. 291). However correct the term may have been legally, given the racist laws which blocked the Issei from shedding alienage through naturalization, it seems a discourtesy at best to continue to refer to them as “aliens.” The commonly used term “American Japanese” to indicate their U.S.-born descendants also replicates the period’s exclusionary exoticization of this population, which even jus soli citizenship did not forestall. For the purposes of this book, the term “Nikkei” will be used to indicate both Japanese immigrants and U.S.-born Japanese Americans in all instances where the original source is not quoted directly. “Nikkei” is a Japanese term used generally to refer to all Japanese émigrés and their descendants. Its usage as a self-identifier by Japanese Americans is a relatively new phenomenon. As such, it is less burdened by some of the problematic historical discourses of the so-called Japanese immigrants and their descendants. It is a comprehensive term that includes all members of the population, both immigrant and U.S.-born, and it sidesteps the bigoted weight of history.

Japanese language terms marking generational differences in immigration— Issei, Nisei, Sansei, and Kibei—were common terminology in the period examined and will also be used throughout this text. “Issei,” or “first generation” were the immigrants to the U.S.; the term “Nisei” marked the “second generation,” the children of the Issei who were the first generation of Nikkei born in the United States. The “Sansei,” the “third generation” were their children. The term “Kibei” was used to differentiate Nisei who were largely raised and educated in Japan. Born in the United States like all Nisei, the Kibei were, usually for financial reasons, sent by their Issei parents to Japan to be reared by grandparents or other relatives.

The Sites

Terminology for the sites of removal and incarceration is both problematic and confusing. The Wartime Civil Control Administration (WCCA) offices

to which the Nikkei were ordered to report to be vetted and registered for removal were variously referred to as Control Stations, Alien Control Stations, and Civil Control Stations. From these Control Stations, the Nikkei were then removed to 17 temporary WCCA “Civilian Assembly Centers,” also called “Reception Centers,” to await further transportation to more permanent WRA incarceration facilities. In California, these temporary detention centers were located in Fresno, Owens Valley (Manzanar), Marysville, Merced, Pinedale, Pomona, Sacramento, Salinas, Santa Anita, Stockton, Tanforan, Turlock, and Tulare. Puyallup, Washington, and Portland, Oregon, were two sites in the Northwest; Mayer, and Parker Dam were the two sites in Arizona.

The next stop in the removal and incarceration process were ten WRA facilities usually called “Relocation Centers” or “Projects” by those running them. These sites of long-term incarceration were located in California, Arizona, Arkansas, Idaho, Wyoming, Colorado, and Utah. Owens Valley and Parker Dam detention centers became, respectively, Manzanar and Colorado River (also known as Poston) Relocation Centers. Tule Lake camp was redesignated Tule Lake Segregation Center in the Summer of 1943. Many scholars, Nikkei and otherwise, also use the term “concentration camps” (Daniels, 1981; Drinnon, 1989; Feeley, 1999; Hirabayashi, 2008; Nishimoto & Hirabayashi, 1995; Weglyn, 1976) to indicate the ten main WRA facilities; the term was also in use during the wartime period by both the Nikkei and others. In this study, I use the terms “concentration camps” and “incarceration camps” interchangeably. The various official designation for the sites of removal and imprisonment are also used as appropriate to the discussion at hand.

Although the history as a whole is most often known as “the internment,” and the WRA relocation facilities are commonly referred to as “internment camps,” the WRA camps should not to be confused with the U.S. Justice Department Internment Camps for “enemy aliens.” Also confusingly called “Detention Centers,” the Department of Justice camps imprisoned individually vetted Nikkei who were designated by the federal government as security risks, as well as their family members, U.S. citizen or otherwise, who elected to be placed with the interned individual. Two “Citizen Isolation Centers”— Moab in southeastern Utah, and Leupp in Arizona—created and run by the WRA were similarly used as detention facilities for Nisei and Kibei marked as “troublemakers” by WRA officials in the aftermath of the Manzanar revolt. For those interested in learning more about the logistics and detailed descriptions of the sites of incarceration, Confinement and Ethnicity: An Overview of World War II Japanese American Relocation Sites (Burton et al., 2000) is an excellent resource.

The Social Workers

A difficulty inherent in writing social welfare history lies in determining the borders of social work. Who can be called a social worker? What comprises the social work role and its domains of activity? What, thus, can be legitimately deemed and critiqued as acts of social work? In analysis of the profession’s early years, when canons of professional education and the margins of professional identity and purview were even more imprecise than they are today, the designation of a particular history as that of social work is especially difficult. The broad definition offered by social welfare historian James Leiby (1962) serves the purposes of this study: “By social workers I mean people interested in the National Conference of Charities and Corrections [now known as the National Conference on Social Welfare] as well as those who, in the twentieth century, held themselves to be professionals” (p. 30). More specifically, throughout the book, the term “social worker” is used to indicate individuals who had training in social work and were employed to perform work which, in the technical jargon of the period, consisted of some form of scientific “social adjustment program” (War Relocation Authority, 1944a, p. 1) for individuals and/or families. Not all those who performed “social work,” however, were trained social workers. Given the massive labor shortages in the war years and the specific difficulty in recruiting trained social workers to work in the remote concentration camps, many functions of the welfare departments were fulfilled by individuals with no education or previous experience in social work. The following chapters attempt to maintain, therefore, a distinction between “social workers” and those performing social work functions.

Excepting the Principle Public Welfare Consultant who served as the Washington “head of the public welfare program for the War Relocation Authority” (United States Civil Service Commission, 1942c, p. 1), social workers in the WRA held job titles of “counselor” of various grades (see Appendix G for job descriptions). In descending order of authority and required social work credentials and experience were Head Counselor (War Relocation Authority, 1942a), Senior Counselor (War Relocation Authority, 1942b), Associate Counselor (United States Civil Service Commission, 1942b), Assistant Counselor (United States Civil Service Commission, 1942a), and Junior Counselor (War Relocation Authority, 1944c). The Head Counselor, in charge of the camp social work department, most often called the “Welfare Section,” required study in “a recognized school of social work” (War Relocation Authority, 1944b, p. 2) and experience in the social work field. The Junior Counselor job description, at the other end of the professional spectrum, listed one year of study in a recognized school of social work and a year of work experience as “desirable qualifications” (War Relocation Authority, 1944c, p. 3).

In the California State Department of Social Welfare (CSDSW) records, the term “caseworker,” “public assistance worker,” and “social worker” were used interchangeably. Although it was not possible to ascertain the professional pedigree of most low-ranking workers mentioned in the records, there is no doubt that “social worker” was a term that identified a particular body of professionals involved in the history. In April of 1942, for example, Martha Chickering (1942), then director of the CSDSW, anticipated “over three hundred social workers being withdrawn from the regular State and county public assistance operations” (Chickering, 1942, p. 3) to work in the various Civil Control Stations. So, too, a CSDSW field report indicated that the “entire registration of the more than 4,500 Japanese evacuated from the Civil Control Stations located in Stockton and Lodi was handled by Social Workers on the staff of the San Joaquin County Welfare Department” (Sundquist, 1942, p. 1). Margaret Leahy (1945) reported in Social Service Review that the removal was executed by “state and local social workers loaned by the California State Department of Social Welfare” (28). In addition “private social work agencies provided volunteer workers, and representatives of the United States Children’s Bureau and the Work Projects Administration gave consultant services” (Leahy, 1945, p. 28).

The social work bona fides of some of the main players in the history were relatively easy to trace. The Nikkei removal (i.e., Alien Enemy Evacuation Program) was a federal program overseen by the Federal Security Agency’s Bureau of Public Assistance and administered through state social welfare departments. Jane Hoey, the director of the Bureau of Public Assistance from 1936 to 1953, and thus a primary overseer in the events, was the 1925 Chair of the New York Chapter of the American Association of Social Workers, the 1928 president of the New York State Conference of Social Work, and the 1940–41 president of the National Conference of Social Work. Azile Aaron, the Bureau’s West Coast regional representative, oversaw the day-to-day affairs of the Nikkei removal. Both Hoey and Aaron are recognized by the National Association of Social Workers (NASW) as “social work pioneers” (National Association of Social Workers, 2004). Martha Chickering, the director of CSDSW from 1939 until her retirement in 1943, was a professor and the one-time director of the Curriculum in Social Service at the University of California, Berkeley. The University of Southern California’s “California Social Work Hall of Distinction” hails her as having made “unique and significant contributions to the emergence of social work education in the state of California, resulting in the establishment of the State’s first professional social work education” (University of Southern California School of Social Work, 2005–2006). Annie Clo Watson, executive director of the International Institute of San Francisco and member responsible for Nikkei issues on the CSDSW Committee on Welfare of the State Council of Defense, was the 1945

winner of the Daniel Koshland Jr. Award for Social Work and a one-time president of the Golden Gate chapter of the NASW (University of Minnesota Immigration History Research Center, 2004). The first in the line of several Social Welfare Consultants who worked in the Washington headquarters of the WRA was Grace Longwell Coyle, prominent group work pioneer and Professor of Group Work at Western Reserve University (later, Case Western) School of Applied Social Sciences. She served as the president of the National Conference of Social Work (NCSW) in 1940, the American Association of Social Workers (AASW) in 1942, and the Council on Social Work Education (CSWE) from 1958 to 1960 (“Grace Longwell Coyle,” 2018).

Source Materials

Archives

The records of social work and social workers found in the archives outlined here are incomplete, in part because records were produced unevenly in the first place and also because some records have, undoubtedly, been lost in the years hence. There are many more sources, including a host of regional archives, that were not investigated for this study; they remain to be discovered and examined by other scholars. Primary data sources which were examined for this book include the records of the YWCA of the U.S.A., located at Smith College; the records of the War Relocation Authority and the Wartime Civilian Control Administration (WCCA), located at the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA); the records of the California State Department of Social Welfare War Services Bureau and the Governor Earl Warren Papers, located at the California State Archives (CSA); the records of the Oregon State Public Welfare Commission and the Governor Charles A. Sprague Collection, located at the Oregon State Archives; the records of the Public Welfare and Social Security Departments and the Governor Arthur B. Langlie Collection, located at the Washington State Archives; the records of multiple social work agencies and organizations located at the University of Minnesota Social Welfare History Archives (SWHA) and the Immigration History Research Center (IHRC); the Hull House Collection and the records of the Immigrants’ Protective League, at the University of Illinois, Chicago; the Grace Coyle Papers at the University Archives, Case Western Reserve University; the Japanese American Relocation Digital Archives and the Japanese American Relocation Reviewed Oral History Collection, at the University of California, Berkeley’s Bancroft Library; and Densho: The Japanese American Legacy Project Digital Archives, based in Seattle, Washington.

The California State Archives

The California State Archives (CSA) in Sacramento, California holds the records of the California Department of Social Welfare (CDSW) War Services Bureau, the social work body which administered the removal process in the state of California. These extensive records, hitherto unexamined, were crucial for this study.4 Departmental records used for this study include general correspondence, interdepartmental and intradepartmental memoranda, staff meeting notes, staff manuals, field reports of supervisors and regional supervisors, and departmental compilations of media clippings. These records detail the role of the CSDSW and that of social workers in the removal, incarceration, and resettlement of the Nikkei. The vast collection includes only a few reports from the other West Coast states; the state archives of Washington and Oregon, also examined for the purposes of the study, themselves contain very few items related to the history. The bureaucratic structure of social work’s involvement in the removal and incarceration was consistent across the states. In all affected states, the county welfare departments reported to state offices, and state offices reported to the regional headquarters of the Social Security Board in San Francisco (Leahy, 1945).5 The State Archives of Washington and Oregon yielded few records of these events, and the miscellaneous copies of correspondence and reports kept in the governors’ records and a handful of other collections do not remotely parallel the massive CSDSW collection held by the CSA. The California data and their analysis offered in this article serve, thus, as a representative sample for the role of social workers throughout the coastal regions.

National Archives and Records Administration I and II

The NARA in College Park, MD hold the records of the WCCA, which administered the removal of the Nikkei from the West Coast and operated the detention centers to which they were first incarcerated. NARA offices in Washington, DC, hold the records of the WRA, the federal agency that executed the longterm incarceration and the resettlement of the Nikkei. The WRA kept extensive, if inconsistent, records and also published a series of reports through the U.S. Government Printing Office. The National Archives holdings include

4 See Origel, K., & Woo-Sam, A. (2000). The World War II Japanese American incarceration: An annotated bibliography of the materials available in the California State Archives (pp. 1–94). Sacramento: California State Library.

5 The Social Security Board (SSB), created in 1935 by the Social Security Act, became part of the newly created Federal Security Agency in 1939 and was renamed the Social Security Administration in 1946 (https://www.ssa.gov/history/orghist.html).

administrative files, official publications, reports and surveys, legal papers, correspondence, memoranda, press releases, photographs and scrapbooks, and much more.

Immigration History Research Center, University of Minnesota

The University of Minnesota Library includes the IHRC and the SWHA. The IHRC holdings examined for this study include the records of the International Institute of San Francisco (1922–1992), established in 1918 as an educational program for immigrant women and girls under the San Francisco YWCA, and the records of the American Council of Nationalities Services (ACNS), which include records and publications of its predecessors the Foreign Language Information Service, the Common Council for American Unity, and the American Federation of International Institutes, and the American Council for Nationalities Service. The ACNS and its predecessors were involved in all aspects of immigration and resettlement, including educational services, ethnic presses and radio, social services, and immigration legislation. Finally, the Annie Clo Watson Papers (1934–1960) collection holds the records of a social worker with long associations with the International Institutes and the YWCA.

Social Welfare History Archives, University of Minnesota

The University of Minnesota’s SWHA is the major repository for the records of social work and social welfare organizations. Both the SWHA and the IHRC hold surprisingly few items related to this history. The examination of these holdings was, therefore, more of an exercise in verifying that relevant materials did not exist rather than one of discovery. The handful of organizations with records of some involvement and interest in the removal and incarceration processes include the Family Service Association of America (FSSA), the AASW, National Social Welfare Assembly (NSWA), National Refugee Service (NRS), and the Survey Associates records, the collection of the organization behind the journals The Survey and Survey Midmonthly.

Sophia Smith Collection, Smith College

One of the most informative sources for this study was the YWCA of the U.S.A. records, held in the archives of Smith College. The YWCA was the only

social work organization with a significant prewar history with the Nikkei, and the records of multiple committees of the YWCA’s National Board show that the organization closely monitored wartime events affecting the Nikkei. The National Public Affairs Committee worked to influence legislation and wartime policies “to guarantee the civil rights of this group” (Briesemeister, 1946, p. 53).

The Race Relations Subcommittee of the National Public Affairs Committee led internal efforts to concretize the vision of the YWCA as an “organization in which differences do not divide” (Briesemeister, 1946, p. 5). Finally, the Japanese American Evacuation Project (JAEP), created on April 1, 1942, was “a special emergency piece of work” (YWCA National Board—Community Division Committee, 1942, p. 2) that recreated the Japanese branches in the WRA concentration camps. The reports of the JAEP fieldworkers, frequent and regular visitors to the ten WRA concentration camps, provide a unique perspective on social work in the camps.

Japanese-American Evacuation and Resettlement Study

Berkeley’s Bancroft Library also holds material collected and/or generated by the Japanese-American Evacuation and Resettlement Study (JERS). Led by Berkeley sociologist Dorothy Swaine Thomas, JERS was one of three in situ studies of the events undertaken by social scientists.6 JERS hired multiple, mostly Nisei, fieldworkers to gather data on the individual and institutional processes of mass incarceration. The study published three volumes of findings: The Spoilage (Thomas & Nishimoto, 1946/1969), The Salvage (Thomas, 1952), and Prejudice, War, and the Constitution (tenBroek, Barnhart, & Matson, 1954). Much scholarship about JERS and stemming from it has also been published. These include Americans Betrayed: Politics and the Japanese Evacuation (Grodzins, 1974), Doing Fieldwork: Warnings and Advice (Wax, 1971), The Politics of Fieldwork: Research in an American Concentration Camp (Hirabayashi, 1999), The Kikuchi Diary: Chronicle from an American Concentration Camp (Kikuchi, 1973), and Views from Within (Ichioka, 1989). The many problems with the study, including the multiple breaches of research ethics inherent in the use of fieldworkers who were inmates living in close proximity with the objects of their

6 The Bureau of Sociological Research (BSR), established at Poston, was another study, one jointly sponsored by the Navy, the Office of Indian Affairs, and the WRA, headed by Alexander Leighton, a psychiatrist and an anthropologist who was also a Lieutenant Commander in the U.S. Naval Reserves (see Leighton, 1945). An anthropologist of the WRA’s Community Analysis Section (CAS) carried out research at each of the internment camps (see Embree, 1944).

study within the concentration camps, can be found elsewhere and will not be analyzed here.7

Among the mountain of texts produced by JERS, including diaries and journals and staff correspondence, reports, and targeted studies, are several analyses of social work in the camps. Of particular interest to this study were the letters and diaries of Mari Okazaki and Charles Kikuchi, and Tamotsu Shibutani’s series called the “Tule Lake Case Documents.” Okazaki’s involvement with JERS was brief, and her name is often omitted from the list of JERS field workers. The San Francisco native received a degree in education from the University of California, Berkeley, where she was an active member of the campus YWCA chapter. After graduation, she worked at the International Institute as a caseworker and assistant to Annie Clo Watson, Executive Secretary of the organization (Okazaki, 1942a) and the appointed member in charge of Nikkei issues on the CSDSW Committee on Welfare of the State Council of Defense. Watson and Okazaki kept in close contact throughout the war years. Like all other Nikkei personnel detailed to the WCCA, Okazaki was eventually sent to her incarceration site as the control stations finished emptying regions of their Nikkei population and closed down the stations. But prior to her confinement at Manzanar, Okazaki worked as “part of the social work interviewing staff” (Okazaki, 1942b, p. 16) in several WCCA stations in San Francisco, San Mateo, Fresno, Reedley, and other locations along the coast. Her letters and diaries, retained as part of the JERS holdings, provide a rare glimpse into the removal process from the perspective of a Nikkei worker.

Mari Okazaki’s decision to work for JERS appears to have been influenced at least in part by the knowledge that Dorothy Thomas could sway the officials to allow the Okazaki family to be sent together to Manzanar from Tanforan, a transfer which had been refused originally. Thomas contacted the Social Security Board and the head of Manzanar on Okazaki’s behest. A series of correspondence, including several telegraph messages, between Thomas and Okazaki shows that confirmation of employment with JERS was the basis upon which assignment to Manzanar for herself and her family depended (Okazaki, 1942a). Her employment was, however, short-lived. In a February 1943 letter to Thomas, Okazaki resigned, remarking: “I should not have taken the responsibility of being one of your field workers nor have submitted you to so much trouble in helping me get my family here with me.” Because she was reluctant to do the job, which required living among the people while “invading their private lives and

7 See, for example, Lane Ryo Hirabayashi’s 1999 book, The Politics of Fieldwork; Ichioka’s 1989 Views from Within; Wax’s 1971 Doing Fieldwork; and Hansen’s 1999 “The Evacuation and Resettlement Study at the Gila River Relocation Center, 1942–1944.”

thoughts” (Okazaki, 1942–43, p. 66), she dreaded being seen as an “informer” (Okazaki, 1942–43, p. 68). In 1943, Okazaki left Manzanar on scholarship to attend the New York School of Philanthropy (now Columbia University School of Social Work), where she earned a master’s degree in social work in 1947 (New York School of Social Work, 1947).

Charles Kikuchi (1942a) was a 26-year-old MSW student at UC Berkeley prior to his removal to Tanforan detention center, then to Gila River concentration camp. He kept detailed journals of daily life in both camps, producing 32 volumes between May 1942 and April 1943.8 He worked in Gila River’s Welfare Section throughout his imprisonment there and was, between his arrival in early September of 1942 and late November, when an experienced social worker finally arrived at Gila to take over the running of the Section, the best credentialed employee of that department (Kikuchi, 1942b). Few Nikkei had any formal training in social work prior to the war, and Kikuchi’s descriptions and frequent criticisms of the WRA and its delivery of social work in the camps are particularly interesting because of his unique position as someone who did have— however limited—some knowledge of social work. Kikuchi left Gila in 1943 for resettlement in Chicago and continued to work as a JERS researcher, chronicling the resettlement process. He eventually completed his social work training, receiving a master’s degree in social work from New York University (NYU) in 1947. He worked as a social worker with the Veterans Administration for the rest of his career.

Materials such as: “22. Social welfare; Social Relations Board; student relocation—Poston Relocation Center, 1942–43,” credited to Tamie Tsuchiyama (1943), and the report entitled “38. Social Welfare Department, Poston Relocation Center, September 29, 1944,” by Richard Nishimoto (1944), were enormously helpful in providing a sense of the workings of the camp from the perspective of Nikkei participant-observers.

Definitively the most troubling, if fascinating, of the JERS documentation on social work are Tamotsu Shibutani’s Tule Lake Case Documents (1943a, 1943b, 1943c, 1943d, 1943e, 1943f, 1943g). Shibutani, incarcerated in Tanforan and Tule Lake from 1942 to 1944, obtained a PhD in sociology from the University of Chicago in 1948; his long academic career, which traversed Chicago and UC Berkeley, ended at the University of California at Santa Barbara. The eponymous case documents were, in fact, analyses of client case notes compiled by the Tule Lake Social Welfare department. Pseudonyms are used in all cases referenced in this study.

8 The finding aid for the full series is available at http://pdf.oac.cdlib.org/pdf/ucla/mss/kiku1259. pdf

Published Sources

Social work’s public documents in the relevant period supplement the primary archival sources. Social work publications examined include The Survey (including its earlier incarnations as the Charity Review and Charities), the Proceedings of the National Conference of Charities and Correction (1875–1916), the Proceedings of the National Conference of Social Work (1916–1924), and writing by social welfare scholars of the period. Social workers did discuss their participation in events and the participation of social workers in a few articles (Ennis, 1943; Freed, 1944; Gottfried, 1944; Hoey, 1942; Lamb, 1942; Leahy, 1946; Nickel, 1942a, 1942b, 1943; Pickett, 1943; Pickett & Morris, 1943; Powell, 1943; Ross, 1944; Schafer, 1943; Webb, 1946). It is difficult to know how to account for this paucity of coverage, but Edith Abbot’s editorial comments in Social Service Review on the California State Department of Social Welfare Biennial report hints, perhaps, at a rationale—other matters took precedence:

This Report of the last biennium is important, not because it covers the first six months of the war, including the Japanese evacuation and other important war programs, but because it also reports on the implementing of the federal requirements regarding the merit system. (1943, p. 242)

Also useful were articles published in scientific and social scientific journals of the period and relevant secondary sources drawn from literature on immigration, historical geography, postcolonial studies, urban history, and the history of social work and social welfare. Finally, some passages and ideas from three previously published articles are replicated here with permission (Park, 2006, 2008, 2013).

References

Abbott, E. (1943). Notes and comments by the editor: Foreign relief and rehabilitation. Social Service Review, 17(3), 362–367.

Briesemeister, E. (1946). America’s children—what happened to us?: Summary report of the Japanese Evacuee Project, January 1942–September 1946, pp. 1–54. Folder 3, Box 721. YWCA of the U.S.A. Records, Sophia Smith Collection. Northampton, MA: Smith College.

Burton, J. F., Farrell, M. M., Lord, F. B., & Lord, R. W. (2000). Confinement and ethnicity: An overview of Japanese American Relocation sites. Seattle: University of Washington Press. Chickering, M. A. (1942). Letter to Richard Neustadt and Azile Aaron, April 13, 1942. Social Welfare—War Services—WCCA—Control Stations—May 1942 (F3729:139). Department of Social Welfare Records, War Services. Sacramento: California State Archives.