AncientGreece

UndertheSpellofStories

Editedby

JONASGRETHLEIN,LUUKHUITINK, andALDOTAGLIABUE

GreatClarendonStreet,Oxford,OX26DP, UnitedKingdom

OxfordUniversityPressisadepartmentoftheUniversityofOxford. ItfurtherstheUniversity’sobjectiveofexcellenceinresearch,scholarship, andeducationbypublishingworldwide.Oxfordisaregisteredtrademarkof OxfordUniversityPressintheUKandincertainothercountries

©OxfordUniversityPress2020

“BeimSchlafengehen”,aus:HermannHesse, SämtlicheWerkein20Bänden.HerausgegebenvonVolkerMichels. Band10:DieGedichte. ©SuhrkampVerlagFrankfurtamMain2002. AlleRechtebeiundvorbehaltendurchSuhrkampVerlagBerlin.

Themoralrightsoftheauthorshavebeenasserted

FirstEditionpublishedin2020 Impression:1

Allrightsreserved.Nopartofthispublicationmaybereproduced,storedin aretrievalsystem,ortransmitted,inanyformorbyanymeans,withoutthe priorpermissioninwritingofOxfordUniversityPress,orasexpresslypermitted bylaw,bylicenceorundertermsagreedwiththeappropriatereprographics rightsorganization.Enquiriesconcerningreproductionoutsidethescopeofthe aboveshouldbesenttotheRightsDepartment,OxfordUniversityPress,atthe addressabove

Youmustnotcirculatethisworkinanyotherform andyoumustimposethissameconditiononanyacquirer

PublishedintheUnitedStatesofAmericabyOxfordUniversityPress 198MadisonAvenue,NewYork,NY10016,UntedStatesofAmerica

BritishLibraryCataloguinginPublicationData Dataavailable

LibraryofCongressControlNumber:2019953207

ISBN9780198848295

DOI:10.1093/oso/9780198848295.003.0001

Printedandboundby CPIGroup(UK)Ltd,Croydon,CR04YY

LinkstothirdpartywebsitesareprovidedbyOxfordingoodfaithand forinformationonly.Oxforddisclaimsanyresponsibilityforthematerials containedinanythirdpartywebsitereferencedinthiswork.

Preface

ThisvolumeisaproductoftheERCresearchgroup ‘ExperienceandTeleologyin AncientNarrative’ (ERCGrantAgreementNo.312321),hostedbyHeidelberg Universityfrom2013to2018.Itsmembers,AnnikaDomainko,JonasGrethlein, LuukHuitink,JakobLenz,andAldoTagliabue,pursuednewapproachesto ancientnarrativebeyondtheavenuespavedbystructuralistnarratology.As manyilluminatingstudiesshow,thetaxonomiesofBal,Genette,andothers provideveryusefultoolsfortheanalysisofancientliterature.Atthesametime, theyarearguablylesssuitableforcapturingphenomenalandexperientialaspects ofreadingorlisteningtonarratives.Andthisisarealdrawbackinthecaseof ancientliterature;asseveralchaptersinthisvolumeargue,ancientcritics(and,we suppose,authorsandreaders)valuedsuchaspectsofnarrativehighly.The HeidelbergERCgroupidentifiedcognitivestudies,togetherwithphenomenology andlinguistics,asopeningupapromisingroadtoamorecomprehensiveunderstandingofnarrativeanditsfunctioninginantiquity.

InMarch2015,thegrouphostedaworkshopon ‘ClassicalLiteratureand CognitiveStudies’ inthebeautifulsurroundingsofKlosterSchöntalinBadenWürttemberg,invitingtwopioneersofthecurrentwaveof ‘second-generation’ cognitivecriticism,KarinKukkonenandEmilyTroscianko.Ourdiscussionson theoreticalissuesandacommunalclosereadingofancientandmoderntexts (Homer,Thucydides,HilaryMantel)provedfruitfulforbothsides,andwas seminalforthedirectionoftheworkofthegroup.InJunethatyear,anequally stimulatingconferenceon ‘NarrativeandExperienceinGreco-RomanAntiquity’ tookplaceatHeidelberg;AnnikaDomainkodeservesespecialthanksfortakingon thelion’sshareofthepracticalorganizationoftheevent.Eightofthepapers deliveredattheconferenceformthebedrockofthisvolume,while fivemorewere solicitedtoincreaseitsscope.Whilethisvolumeisoneofthe finalproductsofthe HeidelbergERCgroup,wehopethatitstriangulationofancientnarrative,ancient criticism,andcognitiveapproacheswillbenomorethanastartingpointfor furtherexplorationsofancienttextsfromvariousperspectives.

Wearedelightedtoseethisvolumeappearasthe firstinstalmentofOUP’ snew bookseries, ‘CognitiveClassics’,andwewishtothankbothserieseditors,Felix BudelmannandInekeSluiter,fortheirinterestandencouragement.Wearealso indebtedtotwoanonymousreadersfortheirincisiveandhelpfulcomments.We areverygratefultoCharlotteLoveridgeforunhesitatinglytakingtheprojectunder

herwing,toGeorginaLeightonforoverseeingallthestagesofthebook’sproduction withcare,andtoDonaldWattforhiswonderfullyrigorouscopy-editing. AtHeidelberg,SabineHug’shelpwasoncemoreindispensableinbringingthe manuscriptintoaformwecouldsubmit;PatrickBaumannexpertlycompiled thebibliography.Finally,JakobStaudeandAngelaTerzaniStaudedeservethanks forgenerouslygivingpermissiontouseoneofthemarvelouspaintingsoftheir father,HansJoachimStaude,forthecoverofthisvolume.Sincewe firstencountered ‘Germaine,VascoandFelice’,ithasnotstoppedintriguingusasitvisually capturessomeoftheintricaciesoftheresponsestoliteraturewhichourvolumesets outtoexplore.

JonasGrethlein,Heidelberg LuukHuitink,Leiden AldoTagliabue,NotreDame

ListofContributors

RutgerJ.Allan isaLecturerinGreekLanguageandLiteratureattheFreeUniversity Amsterdam.

EvertvanEmdeBoas isaPostdoctoralResearcherattheUniversityofOxford.

FelixBudelmann isProfessorofGreekLiteratureattheUniversityofOxford.

CasperC.deJonge isAssociateProfessorofGreekLanguageandLiteratureatLeiden University.

NikolausDietrich isProfessorofClassicalArchaeologyatHeidelbergUniversity.

DavidFearn isReaderinGreekLiteratureattheUniversityofWarwick.

LauraGianvittorioUngar isaPostdoctoralResearcherinClassicsattheUniversityof Vienna.

JonasGrethlein isChairinGreekLiteratureatHeidelbergUniversity.

LisaIreneHau isaLecturerinClassicsattheUniversityofGlasgow.

LuukHuitink isaPostdoctoralResearcherinClassicsatLeidenUniversity.

AnastasiaErasmiaPeponi isProfessorofClassicsatStanfordUniversity.

AlexPurves isProfessorofClassicsattheUniversityofCalifornia,LosAngeles.

AldoTagliabue isAssistantProfessorofClassicsattheUniversityofNotreDame.

AlessandroVatri isaDepartmentalLecturerinClassicalPhilologyattheUniversityof Oxford.

Introduction

NarrativeandAestheticExperienceinAncientGreece

JonasGrethlein,LuukHuitink,andAldoTagliabue

1.TheTearsofOdysseus

WhenDemodocussingsaboutthewoodenhorseinthe Odyssey,Odysseus’ responseisfamouslydescribedbymeansofagraphicsimile:

(Od. 8.52131)

This song thefamousminstrelsang.ButtheheartofOdysseuswasmeltedandtears wethis cheeks beneathhiseyelids.Andasawomanwailsandthrowsherselfuponher dearhusband,whohasfalleninfrontofhiscityandhispeople,seekingtowardoff fromhiscityandhischildrenthepitilessday;andasshebeholdshimdyingand gaspingforbreath,sheclingstohimandshrieksaloud,whilethefoebehindherbeat herbackandshoulderswiththeirspears,andleadherawaytocaptivitytobeartoiland woe,whilewithmostpitifulgriefhercheeksarewastedsodidOdysseusletfallpitiful tearsfrombeneathhisbrows.

(trans.MurrayandDimock1995)

Thesimileprovidesanaptstartingpointfromwhichtothinkaboutaesthetic experienceandancientnarrative.Tobesure,certainaspectsofitsinterpretation

JonasGrethlein,LuukHuitink,andAldoTagliabue, Introduction:NarrativeandAestheticExperienceinAncient Greece In: Experience,Narrative,andCriticisminAncientGreece Editedby:JonasGrethlein,LuukHuitink,and AldoTagliabue,OxfordUniversityPress(2020)©OxfordUniversityPress. DOI:10.1093/oso/9780198848295.003.0001

arecontroversial:¹forinstance,doesthesimileimplythatDemodocus’ song makesOdysseusempathizewithhisvictimsorisheonlyaffectedbythecontrast betweentheheroheusedtobeandthesorry figurehenowcuts?However, regardlessofthenuanceswemaydetectinthesimile,itisaremarkablefactthat Odysseus’ responsetoamererecitalshouldprovokeacomparisonwithsucha profoundexperienceasawomanmourningthedeathofherhusband.Aesthetic experienceistherebyalignedwithahighlyemotional,visceralreal-lifeevent.The comparisongainsadditionalforcethroughadoubleinversion:amalevictoris juxtaposedwithafemalevictim;thishighlightsthedefencelessnessofOdysseus againsttheemotionsinstilledinhimbyDemodocus’ song.Furthermore,apart fromtheinversionsofgenderandrole,thealignmentofOdysseus’ listening with thewoman’ s seeing andtheneven touching herdeadhusbandisalsonoteworthy. Sincesightwasgenerallyconsideredtobemoreintensethanhearinginancient Greece,²thereferencesto ‘seeing’ inthesimilehighlightthevividnessofOdysseus’ emotionalexperience,whilethereferencesto ‘touching’ suggestastillmore intense,embodiedresponse.

NowitmaybethoughtthatOdysseus’ reactionrepresentsaspecialcase, becausehelistensto,andisdeeplymovedby,anaccountofhisownexperiences. ThePhaeacians,afterall,enjoyDemodocus’ performancewithoutanysignsof distress.However,ifOdysseus’ responseisnotparadigmaticofthatofa ‘typical’ memberofabard’saudience,neitheristhePhaeacians’:Alcinousandhispeople livealifeofeasethatisafarcryfromtheworldofheroesandevenmoresofrom thatofHomer’saudience;theirdetachmentis suigeneris.Perhapsitisbestto thinkofthewidelydifferentresponsesofOdysseusandthePhaeaciansasrepresentingtwopolesonawidespectrumofreactionswhichnarrativemayelicitfrom itsrecipients.NarrativecanbereceivedinwaysthatmayremindusofKant’ s ‘disinterestedpleasure’,butitalsohasthecapacitytomoveaudiencesprofoundly, eventoreducethemtotears.

Inanimportantway,however, ‘perhapsOdysseus’stearsmaymoreaccurately figurethenormforHomer’saudienceaswellasforAristotle’ s ’.³Thecomparison oftheactivityoflisteningtonarrativewithanactofseeingandtouching adumbratestherhetoricalconceptof enargeia (usuallytranslated ‘vividness’), whichwasto figureprominentlyinlaterancientcriticaltreatisesandrhetorical handbooks.While enargeia isoftendefined as ‘speech which bringsitssubject matterbeforetheeyes’⁴,referringprimarilytotheexperienceofvisualimagery, ancientcriticswriteasifsuchimagerycomescompletewithsoundsandhaptic sensations;moregenerally, enargeia signifiesthepoweroflanguagetotransport

¹Forbibliography,seeHalliwell(2011)88n.104.

²See,forexample,Plut. Deaudiendo 38a;Hor. ArsP.180ff.Cf.Squire(2016). ³Walsh(1984)5.

⁴ e.g.Anon. Segu.96: ἔ

.Forlistsofancient definitionsalongtheselines,seeManieri(1998)123n.404;Lausberg(1998)35961.

audiencestothenarratedscene.⁵ Theprominenceof enargeia inancientrhetoric andcriticism,towhichwewillreturninSection5below,underscoresthe importancethatancientreadersattachedtotheexperientialqualityofnarrative.

2.Experience:FromStructuralistNarratology toCognitiveStudies

WhereasancientGreekauthorsandcriticsclearlysetmuchstorebytheexperientialqualityofnarrative,thebroadlyconstructivistfocusondiscourseand formalfeaturesofnarrativethatcontinuestodominatethe fieldofClassicshas tendedtobracketthenotionof ‘experience’,probablybecauseitappearstobetoo subjectiveandslipperyatopicforformalandsystematicanalysis.Thus,whilethe taxonomiesofnarrativeofGérardGenette,MiekeBal,andothershavehelped classiciststoexplore,forinstance,thesignificanceofperspective,theorchestration oftime,andthemanyfacetsofvoiceinawiderangeofancientauthors,theyare arguablyill-equippedtodealwith(andnotreallyinterestedin)experience,thatis, withwhatactuallyhappenswhenwereadorhearanarrative.⁶ Anumberof scholarshaveinfactbeguntoregistertheirdissatisfactionwithformalnarratologicalapproachesonthesegrounds.TimWhitmarsh,forone, findsthatthe ‘antisepticformulaeofnarratologists’ areoftenincompatiblewiththeactual ‘experienceofreading’,whileJonasGrethleinhasmadeacasethatafocuson thecategoriesofnarratology,whichhavebeenmostlyderivedfromreadingsof modernnovels,risksoccludingwhatrendersancientnarrativesdistinct.⁷

Meanwhile,recentdecadeshavewitnessedanincreasinginterestinaesthetic experiencebothinsideandoutsideclassicalscholarship.⁸ HansUlrichGumbrecht isonlythebestknownofaseriesofthinkerswhowishtocomplement,ifnot replace,thefocusonmeaningwithafocusonpresence.⁹ Ashecontends,wenot onlyengagewithaestheticandotherobjectsintellectually,butalsoencounter theminmorevisceralways.WithinClassics,Porterhasmadeastrongcasefor theoriginsofaestheticthoughtinancientGreece,andHalliwellhasusedthe dichotomyofecstasyandtruthtoexploreaestheticreflectionsfromHomer toPs.-Longinus.¹⁰ Peponi’sconcernwiththepathologyofexcitedresponsesto

⁵ SeenowespeciallyWebb(2016),andseefurthern.34below.

⁶ See,e.g.,Genette(1982);Bal(1985).ExcellentapplicationsofnarratologytoGreektextsincludede Jong(2004b²)onHomer,Rood(1998)onThucydides,andMorrison(2007)onarchaicandHellenistic poetry.Ingeneral,seetheseries StudiesinAncientGreekNarrative (DeJongetal.(2004))anddeJong (2014),togetherwiththecriticalreviewbyoneoftoday’sleadingnarratologists,Fludernik(2015).

⁷ Whitmarsh(2013)244;Grethlein(2018);(forthcomingc).

⁸ See,explicitly,Grethlein(2015a);Gurd(2016).

⁹ BesidesGumbrecht(2004),seealsoMersch(2002)andSeel(2005²).Relatedmovementsinclude the nuovorealismo ofFerraris(2012)andthenewreceptionoftheHeideggerianheritageinanglophonephilosophy,e.g.DreyfusandTaylor(2015).

¹⁰ Porter(2010);Halliwell(2011).SeealsoPorter(2016).

archaicpoetryandLiebert’ s ‘psychosomaticmodel’ ofaestheticengagementwith Greektragedyarefurthertantalizingexamplesofthisnewinterestinaesthetic experience.Thesefascinatingworks,however,havenotmadenarrativeas opposedtoothermodesofdiscourseaparticularconcernandsofartheyhave nothadamajorimpactonthestudyofancientnarrative.¹¹

WhiletheworkofGenette,Bal,andtheirfollowersfromthe1960sand1970s stillservesasthemainpointofreferenceforclassicists,narrativetheoryhasmoved onandgeneratedapproacheswhichcanbebroadlydescribedas ‘cognitive’ AprimeexampleisMonikaFludernik’spioneeringstudyof ‘naturalnarratology’ , whichputtheideaofexperientialitycentrestage.¹²Otherprominentcognitive narratologistsareDavidHerman,whoreconceiveskeyconceptsofnarratology fromacognitivestandpoint;PatrickColmHogan,whohasaspecialinterestinthe emotionstriggeredbynarrative;CatherineEmmott,whouseslinguisticand cognitivemodelstomapourunderstandingofstories;andAlanPalmerandLisa Zunshine,whohaveadoptedtheconceptofTheoryofMindforliterarystudies.¹³ Theentrieson ‘cognitivenarratology’ inthe LivingHandbookofNarratology,on ‘cognition,emotionandconsciousness’ in TheCambridgeCompaniontoNarrative, andon ‘cognitivenarratology’ in TheRoutledgeEncyclopediaofNarrativeTheory illustratetheimpactthatthecognitiveturnhashadonthestudyofnarrative.¹⁴

Anumberofconceptsintroducedincognitivestudiesareparticularlyusefulif wewishtogivesubstancetothenotionof ‘experience’ innarrative.Oneofthese, whichwillplayaprominentroleinthechaptersthatfollow,is ‘immersion’ ,a conceptwhichtextualscholarshaveadoptedfromgamestudies.¹⁵ Immersion describestherecipient’sfeelingofbeingdrawnintotherepresentedworldandof witnessingwhatgoesonthere.Asthepresentvolumesetsouttoshow,various narratologicalandlinguisticdevicescanleadtoacollapseofthedistancebetween thestoryworldandthereader’sownworldintermsofbothtimeandspaceandso stimulatehertoexperiencethatworldalmostasifitwereasliceofreallife(see Section4belowforanelaborationoftheimportantnotionof ‘almost’).

Anumberofcontributionstothisvolumealsoprofitfromtheinsightsofsocalled ‘second-generation’ cognitiveliterarystudies,whichallowsthemtobring outtheembodiedaspectsoftherecipient’sexperience.¹⁶ Whilea firstwaveof cognitivelyinflectedliterarycriticismwasstronglyinfluencedbyanunderstanding ofthemindascomputational,¹⁷ morerecentworkhasemphasizedtheembodied and enactivenatureofhumancognition.Perception,ithasbeenargued,isnota

¹¹Peponi(2012);Liebert(2017).SeealsoSluiterandRosen(2012);Grethlein(2017).

¹²Fludernik(1996).ForareappraisalofFludernik’sbook,seetheforumin PartialAnswers 16/2 (2018).

¹³Herman(2002);Hogan(2011);Emmott(1997);Palmer(2004;2010);Zunshine(2006).

¹⁴ Cf.Hühn etal.(2018),s.v. ‘cognitivenarratology’;Herman(2007a);andJahn(2005).

¹⁵ Cf.Ryan(2001).

¹⁶ Forgoodintroductions,seeKukkonenandCaracciolo(2014);Caracciolo(2014);Cave(2016).

¹⁷ Foranintriguingadaptationofsuchmodelstoclassicalliterature,seeLowe(2000).

passiveregisteringofourenvironmentconfinedtoindividualsenses,butis stronglylinkedtoactionandinvolvesourentirebody.Ifweassumethatour imaginationworksanalogouslytoourcognition,thisnewviewhasamajorimpact onhowtounderstandourresponsetoliterature.Perhapsmostimportantly,the secondgenerationofcognitiveliterarystudieshasthecapacitytoreorientour assessmentoftextualfeaturesthatrendernarrativeexperiential.Ifourcognitionis embodiedandenactive,thennarrative,inordertobecognitivelyrealist,hastoput apremiumonfeaturesthathaveastrongechointhereader’ssensorimotorsystem.

Theanalysisofnarrativefromthepointofviewofsecond-generationcognitive studiesisstillinitsinfancy,but firstelementsofcognitivelyrealistnarrativeshave beenidentified.¹⁸ Insteadofaimingatpictorialistdescriptions,experientialnarrativesseemrathertointroducethingsasandwhentheymattertotheaction. Afocusonaffordances,thatisonaspectsofthingsrelevanttopotentialinteractionswiththem,alsoconformstooureverydayengagementwiththeenvironment.Accountsofsimplebodilymovementsseemtotriggeroursensorimotor systemwithparticularstrength.Thesequickobservations(andsomeofthe chaptersthatfollowelaborateonthem)alreadysufficetodrivehomethepoint thatacognitivelyinspiredstudyofnarrativeanditseffectsonrecipientswillyield verydifferentresultsfromitsassessmentbytraditionalreaderresponsetheoryas advancedbyWolfgangIser.¹⁹

Admittedly,thedialoguebetweencognitivescienceandliteraryscholarshipis notalwaysaneasyone.²⁰ Scholarswhowishtodeploynotonly ‘softscience’ but also ‘hardscience’,notablyMRIscansshowingneuronalbrainactivity,facethe problemthatthereisstillnoreliablebridgefromtheanalysisofthebraintoan understandingofconsciousness.Thelevelofneuronsthatworkinourbrainsdoes noteasilytranslateintothelevelofsymbolsbywhichweunderstandnarrative. Yetitisincreasinglyacknowledgedbylinguiststhat,contrarytoearlierassumptions,languageisgrounded,notjustinabstract(conceptualandpropositional) representationsalone,butalsointhecomprehender’sperceptual,sensorimotor andemotionalexperience,asreadingwordsandconstructionsactivatesregionsin thebrainassociatedwithvisualperceptionandkinesthesia.Oneofthemostfully worked-outandempiricallytestedtheoriesalongtheselinesisthe ‘Immersed ExperiencerFramework’ ofZwaan,inwhichlanguageisunderstoodas ‘asetof cuestothecomprehendertoconstructanexperiential(perceptionplusaction) simulationofthedescribedsituation’,andcomprehensionas ‘thevicarious

¹⁸ See,forexample,Kuzmičová(2012);Troscianko(2014a).Fora firstapplicationinClassics,see GrethleinandHuitink(2017),whoarguethattheparadoxofHomericvividnesscanbeexplained throughanenactiveaccountofthereaderlyimagination.

¹⁹ Forathought-provokingcomparisonofembodiedmodelsofreadingwithIser’sreaderresponse theory,seeKukkonen2014.

²⁰ Cf.Ryan(2010),and,moreoptimistically,Caracciolo(2014)811;Cave(2016)1521.

experienceofthedescribedsituation’.²¹Evidenceisaccumulatingthatthe ‘depth’ ofembodiedprocessing(the ‘action’-sideofthings)variesdependingonthe kindsoflanguageused,andthatreaders’ andhearers’ responsestowordsthrough theirbodiesmayleadtofully fledgedbodilyfeelings.²²Thechallengeawaiting literaryscholarsistogetabetterandmorenuancedsenseofthelinguisticand narratologicaldevicesthatmaximize(orminimize,forthatmatter)theexperientialityoftexts.

Inadditiontotheresonanceswiththeancientsensitivitytotheexperiential qualityofnarrative,thereisonefurtherpointthatmakescognitiveapproaches appealingtoclassicists.Developedtodealwiththerichvirtualworldsevokedin computergames, ‘immersion’ asacognitiveconcepthasalwaysbeenintendedto covermultiplemodalitiesofourcognitiveandemotivesystems visionand hearing,certainly,butalsothinkofacaptivatedgamermovingalongwith movementsofthecharacterinthegameshecontrols,andoftheexhilaration andfearwhichthatactivitymaybringwithit andtospanvariousnarrative mediaacrosssemioticsystems.Likeliteraryscholars,arthistorianshavebeen stimulatedbyneurologicalresearchintorecipientsofthevisualarts.²³Thiscrossmedialfocuscorrespondstoanassumptionwhichwaswidespreadintheancient world,namelythatlanguageandvisionhaveverysimilareffects,apointcaptured intheformulaof utpicturapoesis.²

3.TriangulatingModernTheory,Ancient Narrative,andAncientCriticism

Inspiredbyrecentdevelopmentsincognitivetheoryandtheirstrongresonancein ancientmaterial,thisvolumeexplorestheexperientialdimensionofancientGreek narrative.Inparticular,itwishestoestablishatriangularconversationbetween moderntheory,ancientnarrative,andancientcriticism,intheconvictionthat eachofthesebranchesofscholarshipstandstobenefitfromsuchaconversation. Firstofall,thefocusonexperientialityincontemporarynarratologicaland cognitivecriticismopensupnewandimportantaspectsofancientGreeknarrativesthataredifficulttocaptureotherwise.²⁵ Conversely,ancientmaterialis ‘good tothinkwith’,asitallowsustoreconsideranumberofmoderntheoreticaltenets

²¹Zwaan(2004)36.ItismorefullyintroducedbyAllan(Chapter1ofthisvolume).

²²SeeZwaan(2009;2014);SanfordandEmmott(2012)10331;KuijpersandMiall(2011).

²³SeeFreedbergandGallese(2007);DiDioandGallese(2009);withthequalificationsofGallagher (2011).

²⁴ SeeWebb(2009);Squire(2009).

²

⁵ ForotherattemptstogobeyondtheframeoftraditionalstructuralistnarratologyinClassics,see GrethleinandRengakos(2009);CairnsandScodel(2014).Foracognitiveapproach,seeAnderson, Cairns,andSprevak(2019),whichcontainsseveralchaptersthatdealdirectlyorindirectlywith narrative.

thatseemtobeuniversalbutoftenturnouttobeessentiallyshapedbytheslim canonofmodernliteratureonwhichtheoreticianshavetendedtofocus.²⁶ Furthermore,thelongtraditioninclassicalscholarshipofpayingcloseattentionto usageandstylecanbemadeproductiveformoderntheory,asclassicistsareina goodpositiontohelpgiveconcretelinguisticsubstancetoconceptslike ‘immersion’ and ‘experience’ asusedbymoderncritics.Finally,itisusefultoinclude ancientcriticisminthedialoguesetupinthisvolumeforatleasttworeasons.On theonehand,theprominenceinancientcriticalandrhetoricaltheorizingof conceptssuchas enargeia fullyjustifiesanapproachtoancientGreeknarrative thatfocusesonitsexperientialdimensions.²⁷ Ontheotherhand,ourreadingsof ancientcriticismcanberefinedbyconsideringitsaimsandmethodsagainstthe backdropofmoderncognitivetheory.²⁸

Thisvolumeisdividedintothreeparts.Itopenswithasetofchaptersonancient narrative:AllantacklesHomerandThucydides.Fearndiscussesawiderangeof lyricpoetryfromStesichorusandPindartoBacchylidesandAnacreon.Budelmann andVanEmdeBoasfocusonthemessengerspeechinGreektragedy.HaureconsidersHellenistichistoriographyinthelightofDiodorusSiculus.Finally,Tagliabue analysesthe ShepherdofHermas,anapocalyptictextfromtheImperialEra.

Whilethechaptersofthe firstpartarearrangedinchronologicalorder,the secondpart,whichisdevotedtoancientcriticism,proceedsfromlesstomore technicalformsofreflection.ItstartswithGrethlein’schapterontheimplicit meditationonexperienceandnarrativeinHeliodorus’ Ethiopica.DeJongediscussestheideaof ekstasis inPs.-Longinus.Purvesteasesoutthesignificanceof hapticmetaphorsinDionysiusofHalicarnassus’ rhetoricalandliterarytreatises. Huitinkreassessestheancientconceptof enargeia throughananalysisofsomeof themostimportantsourcesagainstthebackgroundofrecentcognitivelyinflected reader-responsestudies.Vatridemonstratesthesalienceofexperienceforancient theorizingonasinglerhetorical figure,asyndeton.

Thechaptersformingthethirdpart, finally,broadentheperspectiveofthe volumebyinquiringintothemediumandcontextofnarrativeandinnegotiating therangeofaestheticexperience.Gianvittorio-Ungarusesatantalizingancient commentonaperformanceofAeschylus’ SevenagainstThebes inAthenaeusto highlighttheimpactofdanceontheresponsesofancientaudiencestoGreek tragedy.Dietrichexpoundsonthe ‘narrativesting’ ofvisualart,especiallyin incompletesculpturesoftheImperialAge.Inthe finalchapter,Peponimakesa casefora ‘livedaesthetics’ inancienttextsthatchallengestheneatconfinementof aestheticexperienceinmostmoderndiscussions.

²⁶ Forthisapproach,seealsoGrethlein(2015a),(2015b),(2017).

²⁷ Morebroadly,ontraditionsofknowledgeandtheirperformativedimensionintheancientworld, seeFuhrerandRenger(2012).

²⁸ SeeonthispointHuitink(2019),esp.pp.1756.

Asthisbriefsurveyillustrates,wefollowtheinclinationofmostcurrent narratologistsbyadoptinganencompassingnotionofnarrative.Whereasmany classicistsstilladheretoarathernarrowdefinitionofnarrativeaspredicatedon theexistenceofanarrator,mostnarratologistsnowrelyonbroaderconcepts whichallowforintergenericandintermedialcomparisons.²⁹ Ifthelongdebate abouthowtodefinenarrativehassomethingtotellus,thenitisthatthereisnota single, ‘correct’ conceptofnarrative,butrathervariousconceptswithdifferent heuristicvalues.³⁰ Forthepurposesofourvolume,acomprehensivedefinitionis mostapt.Theresponsesthatstorieselicitdonotdependonanarratorialinstance butcanalsobetriggeredbystorieswhicharenotmediatedbyanarrator.We thereforeunderstandnarrativeastherepresentationofasequenceofactionsina sequentialmedium.Inadditiontoepic,historiography,andthenovel,thisvolume alsoembracesdrama,lyricpoetry,andapocalypticliterature.Onecontributionis evendevotedtovisualart,whichmaycontaina ‘narrativesting’.Thoughtheyare notexplicitlyclassifiedassequentialforms,non-narrativelyricandvisualarthave thecapacitytostimulatetheirrecipientstotransformthescenesrepresentedinto sequencesofactionandarethereforeofgreatinteresttoaninvestigationof narrativeandexperience.

4.AncientNarrative:Immersion,Distance,andFurther AspectsofAestheticExperience

Thechaptersinthisvolumeseektoestablishamultifacetedpictureofnarrative andaestheticexperience,whichisnonethelessunifiedbyanumberofcommon threads.Onecentralconcept,whichwasalreadymentionedabove,is ‘immersion’ . Itisintroducedinthe firstchapterafterthisintroduction(Allan)andisthen harnessedinnearlyallsubsequentchapters.AsAllanargues,immersionmay causereadersorlistenerstoexperienceasenseofbeingtransportedtothesceneof theactionandofbeingabsorbedbythenarratedeventsastheyunfold.SubsequentcontributionsdevelopAllan’sviewsonimmersioninseveraldirections.As AlexPurvesbringsoutinherinvestigationofDionysius’ criticism,thefeelingof beingimmersedisnotonlyvisual,butalsohaptic adiscoverywhichresonates interestinglywithenactivistaccountsofcognition.Immersioncanalsoproduce powerfulemotionaleffects.DeJongeandVatriusethelensesofPs.-Longinusand ancientrhetoricaltheoryrespectivelytodiscussthestrongemotionalidentificationwiththecharactersinastory,anotionwhichHuitinkaimstomakestillmore

²⁹ See,e.g.,W.Wolf(2002);Ryan(2004);Meister(2005).

³

⁰ Thecomplexityofthedebateandthevarietyofdefinitionsproposed,discussed,andchallengedin narratologyaretangibleinthat,atleastuntilnow,the LivingHandbookofNarratology doesnotfeature anentryfor ‘narrative’:seeHühn etal.(2018).Forasuccinctsurvey,seeRyan(2007).

preciseandtangiblebyapplyingtheconceptof ‘bodily mimesis’ toancientcritical commentson enargeia

ThechapterbyBudelmannandVanEmdeBoascanhelpushonethedefinition ofimmersioninadifferentway,asitdistinguishesbetweenseveralmodesby whichaudiencesmayattendtoatragicmessengerspeech.Theaudienceofthe messengerspeechin Hippolytus canbetransportedtothecoastalplainand Hippolytus’ chariotride,themostobviousformofimmersioninthiscase.They can,however,alsobeabsorbedintheinteractionbetweenTheseusandHippolytus’ messenger,whoisconveyingthisstory;thisstillcountsasimmersion,because theaudiencedirectsitsattentiontothestoryworldofthedrama.Athirdlevelat whichtheaudiencecanengagewiththeplayistheactors’ mesmerizingperformance.Nowthisdoes not qualifyasimmersion,asheretheaudience’sattentionis levelledattheactofrepresentationinsteadoftherepresentedworldandaction.

Asstrongasimmersionmaybe,itis withveryoccasionalexceptions balancedbyanawarenessthatoneisattendingtoarepresentation.Suchawarenessisinfactacrucialaspectofaestheticexperienceingeneral:³¹afterall,without it,totakeanexamplealsousedbyDietrichinhischapter,Myron’slifelike sculptureofacowwouldjustbe ...a cow.³²Thebalancebetweenimmersion andreflectionseemstochangeconstantlyinthereadingprocess:sometimesthe pullintothenarratedworld flaresup;sometimesthemediationisfeltwith particularintensity.Inhisexplorationofthe Ethiopica,Grethleindemonstrates thatHeliodorususesembeddedstoriestomeditatewithgreatnuanceonthe dynamicconcomitanceofimmersionandreflection.Thismeditation,Grethlein proposes,canhelpustoquestiontheassumption,deeplyingrainedinpoststructuralistthought,thatexperienceandreflectionarenecessarilyatloggerheads.

Thetensionbetweenimmersionandreflectionisobvious,andyet,inaddition tobeingyokedtogetherinaestheticexperience,thesetwoaspectsofresponse mayalsomutuallyreinforceeachother.Thus,onecanaskifitisbecauseof theconvincingperformanceoftheactorsof Hippolytus thatis,becauseofthe performance’simmersivepull thattheaudiencecomestoadmiretheactors,or, conversely,ifthesensethattheactorsputonaconvincingshowmakesthe audienceallthemoreeagerto ‘stepinto’ theillusionthattheyarewatching TheseusandHippolytus’ messenger.Wheninthe Ethiopica CnemonbegsCalasiristohurryupwithhisnarration,healertsthereadertothemediation,butmay equallypullthereaderdeeperintoCalasiris’ narrative,asthepostponement heightensthesuspenseofthestory.DeJongeshowsinhiscontributionhow

³¹ThisisanimportantpointmadefromdifferentperspectivesandindifferenttermsbyWalton (1990);Schaeffer(1999);Wolf(2014).ItisencapsulatedinHusserl’sphenomenology,onwhich,see Grethlein(2015a).

³²Theideathataestheticexperiencedependsonbothrecognizingtheillusionandbeingtakeninby italreadyplaysanimportantroleinancientdiscussions,someofwhichfocusonMyron’ scow,on whichseeSquire(2010);Wessels(2014).

Ps.-LonginusissimilarlysweptoffhisfeetbytheirrationalemotionsofaSapphic poem,butsimultaneouslyadmiresitastheproductofarationalmind.

Asimportantasthebalancebetweenimmersionandreflectionis,itdoesnot exhausttherangeofaestheticexperience.Inhisrecentbook Dissonances,Gurd outlinestheauditoryaestheticsofarchaicandclassicalpoetry.³³Greekpoets,he shows,putapremiumon ‘sound’,whichaffectstheaudienceinanon-semantic way.Inthisvolume,Fearntacklessamplesfromlyricalpoetrytoshowthatpoetic texturehasthepowertoenthraltherecipient.Rhythmorpatternsofsoundmay distractthereaderfromtherepresentedworldandnonethelessspellbindthe reader,intensifyingherexperience.Atthesametime,suchformalelementsmay ultimatelyhelptopullthereaderintotherepresentedworld;asPurvesdemonstrates,DionysiusofHalicarnassusexpoundedonsucheffects.

Audiencesandreadersmayalsobeengagedinamoreintellectualway.Allan touchesondetachedaccountsinThucydideswhichmakereadersview,andreflect on,theeventsfromadistance.Atersereferencetoamassacreinsteadofavivid accountmayhaveashockingeffectorpromptacriticalevaluationofthecircumstances.Inhisreadingofthe ShepherdofHermas,Tagliabueshowshownonsequentialformsofnarrativejoltreadersoutofanimmersivereadingandlead themtoexperiencethetimelessnessofthedivinethroughamoredistanced, thoughtfulsortofengagementwiththetext.

Theexperientialqualityofnarrativenotonlyhasmanyfacets,butcanalso serveavarietyofpurposes,asthechaptersofthisvolumeshow.Haudemonstrates thatthesensationalismforwhichcertainHellenistichistoriographershaveoften beendenigratedalsoconstitutesameansofdrivinghomemoralmessages. Afocusontheexperientialqualityofthisperceivedsensationalismthusmakes usseetheworksofauthorslikeDurisofSamosandPhylarchusinanewlight. Tagliabueproposesthatthe ShepherdofHermas usesthemeansofnarrativeto supportthetheologicalagendaofthetext,inordertoleaditsreaderstoan experienceoftheChurchandofthetimelessnessbefittingitsdivinenature.By tryingtoexpresswhatisultimatelybeyondrepresentation,the Shepherdof Hermas probesthelimitsofnarrativeanditsexperientialdimension.AsDietrich argues,thenarrativeappealinherentinincompletesculpturesformspartofa broaderaestheticsofthevoidinImperialculture,whichcanalsobetracedinthe mediumofpantomime.

5.NarrativeandExperienceinAncientCriticism

FromitsbeginningstotheImperialera,ancientGreekliteratureishighlyreflexive. Odysseus’ responsetoDemodocus’ songinthe Odyssey andCnemon’sabsorption ³³Gurd(2016).

inthe Ethiopica illustratethattheexperientialqualityofnarrativeattractedhighly nuancedreflections.Itis,therefore,nosurprisethatancientcriticismandrhetoric developedarichterminologytotalkabouttheexperientialaspectsofreader response,includingsuchimportantconceptsas enargeia,whichisdiscussedin Huitink’scontribution,and ekstasis,whichDeJongeshowsplaysanimportant roleinPs.-Longinus’ treatise OntheSublime.Ps.-Longinusfurtherillustratesthe factthatitisnotonlyliterarytextswhichblurtheboundariesbetweenliterary practiceandcriticism.WhileHeliodorusfeaturessomeofthemosttrenchant reflectionsonnarrativeandexperiencetohavecomedowntousfromantiquity, Ps.-Longinusinsomepassagesenactswhathedescribes.

Itis,ofcourse,notalwayseasytointerpretancientcriticisminthelightof modernconcepts.Thisisinpartbecauseancientcriticsdrawsustenancefrom contemporarytheoriesofperception,memory,andlanguagewhicharenotour own.Thus,whentheyusetermssuchas ‘entrance’ (thelgein), ‘bewitch’ (kēlein ) or ‘knocksideways/astound’ (ekplēttein)totalkabouttheimpactofdiscourse, theyoperateontheassumptionthatlanguage(logos )isaphysicalforcewhich literallyimprintsitselfonthemind.Suchtermsdonotnecessarilyoverlapwith modernterminologyusedtodescribetheexperientialaspectsofreaderresponse. Ancientcriticsalsodonotsingleoutnarrativediscourseinparticular,as logos isa moregeneralconcept.Still,Quintilianmentions enargeia asa virtusnarrationis (Inst. 4.2.63)andVatrishowsthat,interestinglyenough,whenancientcritics associatepeculiarlyimmersiveeffectswithasyndeton,itisfromnarrativepassages thattheytendtodrawtheirexamples.

Despite,orratherbecauseof,thedifferencesfrommoderntheory,thestudy ofancientcriticismhasalottocontributetothethree-wayconversationwhich thisvolumewishestoestablish.Forinstance,Huitink’scontributionon enargeia andPurves’ chapteronthehapticqualitywhichDionysiusdiscernsinthephonetic andstylisticfeaturesofanOdysseanpassageshowhow,ontheonehand,certain hithertoalienatingaspectsofancientcriticismappearinanewlightwhenconfrontedwithrecentcognitiveapproaches,andhow,ontheotherhand,ancient critics’ closereadingsrevealasensitivitytostylisticminutiaewhichwehavelostbut woulddowelltoregain.Ingeneral,ancientconceptsoftenturnouttobemore multifacetedthanoneexpects.Forinstance,theancientconceptof enargeia includespreceptstodo,notonlywithdetaileddescription,butalsowithphonetic effects,onomatopoeicdevices,epithets,variouskindsofverbalrepetition,andeven temporalfeatures,especiallythegradualunfoldingofeventsandtheuseofthe historicpresent.³⁴

³⁴ SeeAllan,DeJong,andDeJonge(2014;2017)foracomparisonbetweentheancientconceptof enargeia andRyan’s(2001) ‘immersion’,andHuitink(2019)foranembodied,enactivistreadingofthe concept.Goodsurveyswhichemphasizethevarietyofdevicessaidtocontributeto enargeia are Meijering(1987)3944;Manieri(1998)79192;Otto(2009)67134;Webb(2016).

ThevastpotentialofancientreflectionscomestotheforeinPeponi’sargument. Modernaesthetics,notablyundertheinfluenceofKant,tendstofocusonthe (usuallyquitebrief)periodoftimeweactuallyattendtotheobjectofanaesthetic experience.Thisis,however,anartificiallimitation,sinceaestheticexperience continuestoresonateafterwehaveattendedtotheaestheticobjectitself.From passagesinPs-Longinus,Lucretius,andLibanius,Peponiderivesamoreinclusive ‘livedaesthetics’ thatdoesjusticetothewiderrepercussionsofaestheticexperiencesinthemodernaswellastheancientworld.Peponi’scasenicelyillustrates thereciprocityofthetriangularconversationbetweenancientnarrative,ancient criticism,andmoderntheory.Notonlycanourunderstandingofancientmaterial benefitfrommodernaesthetics,butancientreflections,whetherexplicitincriticismorimplicitinnarrative,alsohavethepowertochallenge firmlyestablished, butquestionabletenetsofouraestheticagenda.

Bynomeansdoesthisvolumeaimtotreattheexperientialqualityofancient narrativeanditsconceptualizationinancientcriticismexhaustively.Itdiscusses whatwehopeisafairandrepresentativeselectionoftextsfromthearchaictothe Imperialerasandcoversthemostimportantaswellassomeminorgenresof ancientnarrative.Thereare,however,manyothertextsthatwouldbenefitfrom ananalysisalongthelinessketchedinthisintroduction.Bythesametoken, immersionanditsintricaciestakecentrestageinthisvolume.Giventheprominenceofimmersivefeaturesinancientnarrativeandtheirsalienceinancient criticism,thisfocusseemsjustified;atthesametime,thediscussionofother aspectsofthereader’sresponseinsomechaptersindicatestheneedforfurther explorationsof,say,theeffectofsoundandotherfeatures.Wethereforehopethat thetriangulationofmoderntheory,ancientnarrative,andancientcriticism proposedinthisvolumewillstimulatefurtherstudiesinthecognitivedimension ofancientnarrative.

NarrativeImmersion

SomeLinguisticandNarratologicalAspects

RutgerJ.Allan

1.ExperientialityandImmersion

Agoodstoryislikelife.Byrepresentingexperiencesinsuchawaythattheyappeal toreal-lifeexperiences,agrippingstoryisabletogivethereaderthefeelingof beingpartofthestoryworld:thereaderseeswhatthecharacterssee,thinkswhat thecharactersthink,andfeelswhatthecharactersfeel.AccordingtothenarratologistMonikaFludernik,thequalityof experientiality , ‘thequasi-mimeticevocationofreal-lifeexperience’,¹shouldberegardedasthedefiningcharacteristicof narrativeratherthan,forexample,plotstructure.ForFludernik,narrativeisa subjectiverepresentationofactions,intentions,andfeelings filteredthroughthe mediumofconsciousness: ‘narrativityisprimarilybasedonaconsciousnessfactor ratherthanonactantialdynamicsorteleologicaldirectedness’.²Inotherwords, narrativity is experientiality.Eventhoughmanynarratologistsmaynotgosofar asto equate narrativitywithexperientiality,mostwillagreethatexperientialityis indeedacrucialelementofnarrative.³

Narrativeexperientialityhastwoaspectsthatareintimatelyconnected:onthe onehand,itinvolvestherepresentationofhumanexperiencesinthetext;onthe otherhand,itrelatestothecapacityofanarrativetexttoeffectacertain psychologicalexperienceforitsrecipient(listenerorreader).Thetightinterplay betweenthesetwoaspectsofexperientialityisalsoevidentinthephenomenonof immersion,whichwillbethemainfocusofthispaper.

¹Fludernik(1996)12.²Fludernik(1996)30.

³ForsomegeneralpointsofcriticismonFludernik’sview,see,e.g.,Herman(2002)1405. AccordingtoHerman(2002)922,narrativeismoreadequatelycharacterizedbythepresenceof fourbasicelements:(i)situatedness(inaspecificdiscoursecontext),(ii)eventsequencing(structured timecourse),(iii)worlddisruption(introductionofadisequilibriumintothestoryworld),(iv) ‘what’sit like’ (howsomeconsciousnessexperiencestheworlddisruption).Thelastelementcanberoughly equatedwithFludernik’sexperientiality.OneoftheproblemswithFludernik’sexperientialdefinition ofnarrativityisthatitblursthegenreboundarybetweennarrativeandlyric.Grethlein(2015a) criticizesFludernik’sconceptionofnarrativebypointingout(throughananalysisofHeliodorus’ Ethiopica)theimportanceofthetemporaldynamics,morespecifically,plotdevelopmentforthe experientialityofnarrative.

RutgerJ.Allan, NarrativeImmersion:SomeLinguisticandNarratologicalAspects In: Experience,Narrative,and CriticisminAncientGreece Editedby:JonasGrethlein,LuukHuitink,andAldoTagliabue,OxfordUniversityPress (2020)©OxfordUniversityPress. DOI:10.1093/oso/9780198848295.003.0002

Awell-knownpsychologicaleffecttriggeredbyworksofartistheaudience’ s feelingofbeingmentallydrawnintotheworldthatisrepresentedbytheworkof art.Inthe fieldofnarratology,thispsychologicalphenomenonisreferredtobythe term immersion ⁴ Thisnotionhasbeenintroducedintothe fieldofcognitive narratologybyMarie-LaureRyan⁵ andithasrapidlygainedgroundacrossvarious otheracademicdisciplinessuchasvisualart,drama,and filmstudies.⁶ Itgoes withoutsayingthatthisincreasinginterestinthephenomenongainedconsiderableimpetuswiththedevelopmentofnewtechnologies(suchas3Dcinema, computergaming,andvirtualreality)whichaimatenhancingthesubject’sfeeling ofbeingimmersedinavirtualworld.

Immersioncanbedefinedasthefeelingofbeingtransportedtoavirtualworld totheextentthatoneexperiencesit uptoapoint asifitweretheactualworld.

The ‘uptoapoint’ isanimportantprovisointhedefinition.Theexperienceof beingimmersedinanartificialworldhingesonawillingsuspensionofdisbelief: animmersedreaderorspectatorwillinevitablyretainsomedegreeofselfawarenessandawarenessoftheactualphysicalworldsurroundinghimorher. Animmersedreader/spectatorwillalsoremainawaretosomedegreethatthe worldrepresentedbytheworkofartisnottheactualworld.⁷ Thismeansthata completeimmersioninthestoryworldtotheextentthatone,withoutany reservation,takesitastheactualworldisimpossible.⁸

Theintensityoftheexperienceofbeingimmersedisdependentonvarious cognitiveandemotionalpropertiesoftheimmersedsubjectbutitisobviously alsodeterminedbyparticularfeaturesoftheworkofart(or,morespecifically,the text)thatismeanttoelicittheimmersiveexperience.Intheconceptionofthe ImmersedExperiencerFramework(IEF)developedbythecognitivepsychologist RolfZwaan:

⁴ SeeRyan(1991),(2015[2001]).Therearevarioustheoreticalconceptsfromdifferentresearch traditionsthataresimilartoimmersion: entrancement (Nell(1988)), psychologicalparticipation (Walton(1990)), transportation (Gerrig(1993);GreenandBrock(2000))or aestheticillusion (Wolf (1993),(2004);Wolf,Bernhart,andMahler(2013)).Thesestudieshavebeenofcrucialimportanceto ourunderstandingofimmersion.Anexcellentintroductiontothe fieldofresearchisWolf ’sentry ‘Illusion(Aesthetic)’ intheonline LivingHandbookofNarratology (Hühn etal.(2018)).

⁵ SeeRyan(1991)213.

⁶ Inher1991book,Ryanmoreprominentlyusestheterm ‘recentering’ todescribethereader’ s transportationtoa fictionalworld.Theterms ‘immersion’ and ‘immersive’ haveemergedinvirtualrealitytechnologytodescribeauser’sexperienceofbeingphysicallypresentinasimulated,computergeneratedenvironment.SeealsoRyan(2015[2001])andWolf,Bernhart,andMahler(2013).

⁷ Ourresidualawarenessofourrealenvironmentwhenweattendtoastoryandourrealizationthat thestoryworldisnot ‘real’,evenifwearefullyimmersed,isalsodiscussedbyGrethlein(2015),pointing outthatourreceptionofnarrativeisnecessarily ‘bracketedby “as-if”’ andshowingthataesthetic experiencehingesonintricateinterplaybetweenimmersionandamorereflectivestancetowardsthe narrative.SeealsoWolf(2004)328;Grethlein(Chapter6ofthisvolume);andBudelmannandVan EmdeBoas(Chapter3ofthisvolume).

⁸ Completecognitiveimmersionwouldcomeclosesttohavingadreamorhallucination.Whenwe aredreaming,wearenotremindedoftherealworldasweareinthecaseofnarrativeimmersion:wedo nothaveabookinourhandsorarewatchinga filmscreen.Emotions,therefore,affectadreamerinan unrestrainedway,notcurbedbytherealizationthattheexperiencedworldisinfactnottherealworld.

languageisasetofcuestothecomprehendertoconstructanexperiential (perceptionplusaction)simulationofthedescribedsituation.Inthisconceptualization,thecomprehenderisanimmersedexperiencerofthedescribedsituation,andcomprehensionisthevicariousexperienceofthedescribedsituation.⁹

Zwaan’sIEFisan embodied theoryoflanguagecomprehension.Theideabehind theembodiedunderstandingoflanguageisthatwordsactivateregionsinthe brainwhicharealsoinvolvedwhenthesubjectisactuallyexperiencingthe referentoftheword.Whenreadingasentenceinanarrative,theimmersedreader willconstructamentalrepresentationthatisgroundedinthesamesensory, motor,andemotionalsourcesinthebrainasthereal-lifeexperience.¹⁰ Itshould benotedthatZwaan’sconceptionofthereaderasan immersed experienceris broaderthanthenotionofreaderlyimmersionasintendedinthischapter. Zwaan’sclaimisthatareaderasalanguagecomprehenderwilltapintothe samesensorimotorsourcesasreal-lifeexperienceandtherebyvicariouslyexperiencethedescribedsituation.Narrativeimmersionasitisconceivedofinthis chapterisamorespecificphenomenon.Itnotonlyinvolvesavicariousexperience ofthedescribedscene,butalsonarrativeimmersionadditionallyinvolvesthe feelingofbeingtransportedtothestoryworld,whichrequiresthereader’sreduced awarenessoftheactualworldandofthetextasthemediumoftherepresentation.

Inamorerecentpublication,Zwaantakesamorenuancedstancetowardsthe claimthatlanguagecomprehensionisfullygroundedinthebrain’ssystemofaction, perception,andemotion.¹¹Zwaanproposesapluralistviewofcognitioninwhich,in somecontextsoflanguageuse,comprehensionismorestronglygroundedin perceptionandaction(grounded,embodiedviewofcognition),while,inother contexts,comprehensionmorestronglyinvolvesthemanipulationofabstract,amodalsymbols(symbolicviewofcognition).Thispluralistandscalarviewoflanguage comprehensionhelpsustounderstandatleastoneaspectofnarrativeimmersion.¹² Immersivetextswillinvitethereadertoconstructamentalrepresentationofthe describedsituationthatisgroundedinperception,action,andemotion,whilenonimmersivetextslackaclearlydefinedspatio-temporalframeworkandcentrearound abstractconceptsthatarenot(directly)groundedinsensorimotorexperience.

Theexperienceofimmersionisascalarphenomenon.Readerscanfeelthemselvesbeingimmersedinthestoryworldtovariousdegrees.Themoreatext enablesthereadertoconstructanexperientialsimulationofthedescribedsituation(e.g.bymeansofwordsorotherlinguisticcues),themoreintensethefeeling ofimmersionwillbe.

⁹ Zwaan(2004)36.

¹

⁰ Foranoverviewofembodimenttheoryandempiricalstudiesoftheexperientialaspectof narrativeunderstanding,IrefertoSanfordandEmmott(2012)13260.Anintroductiontothestudy ofembodiedcognitionisBarsalou(2010).

¹¹SeeZwaan(2014).

¹²Ithanktheeditorsforpointingthisouttome.SeefurthertheIntroduction,Section2.

Whatarethetextualcuescapableofevokinganimmersiveexperienceinthe reader?Inrelationtoliterarytexts,anumberoftextualfeaturesservingto transportthereadermentallytothescenearediscussedbyRyan.Asimmersive devicesshementionssuchdiverseelementsasinternalandvariablefocalization,¹³ scenenarration,dialogueandfreeindirectdiscourse,prospective(ratherthan retrospective) first-personnarration,atotallyeffacednarrator, mimesis ‘showing’ (ratherthan diegesis ‘telling’),andreassignmentofthereferenceofdeicticelementstotheperspectiveofaparticipantinthescene.¹⁴

BuildingonRyan’swork,Iwouldliketoproposeasetoflinguisticand narratologicalelementswhichIconsidertobeconducivetoimmersion.Inthe followinglist,Icategorizetheimmersivefeaturesunder fivegeneralheadings: Verisimilitude,Perspective,Transparency,InterestandEmotionalInvolvement, andthePrincipleofMinimalDeparture.¹⁵

(I) Verisimilitude:Thetextevokesalifelike(‘vivid’)mentalrepresentationof persons,objects,actions,andtheirsetting.¹⁶ Alifelikerepresentation:

(a)focusesonconcrete,physicalobjects;

(b)providesgraphicsensorydetails;

(c)providesdetailedspatialinformation;¹⁷

(d)progressesatarelativelyslowpace(scene narration:narrationtime approximatesnarratedtime);

(e)advancesinchronologicalorder(no flashbacks/flashforwards)

(f)activates(cultural)knowledgeschemas(cognitiveframes)whichenable theaddresseeto ‘completethepicture’ mentally.¹⁸

¹³At firstglance,onemightsuspectthatvariablefocalization,theshiftinthefocalizationfromone charactertoanother,disturbsthefeelingofimmersion.However,itseemsthathumanspossessa considerablecognitivecapacitytoprocessshiftsinperspectivewithouttherebeinganydetrimenttothe feelingofbeingimmersedinascene.Forexample,intheopeningsceneofthe film SavingPrivateRyan at OmahaBeach,asceneoftenpraisedforitsimmersivequalities,thecamerastandpointshiftscontinually, sometimestakingthepointofviewofoneofthesoldiers(subjectiveshot),sometimestakingaperspective thatcannotbeidentifiedwithacharacter(objectiveshot).Thiscontinuousshiftinpointofview(between subjects,aswellasfromsubjectivetoobjectiveandback)isinnowaydetrimentaltotheaudience’sfeeling ofbeingimmersedinthebattlescene.Iwillreturntothisissueatalaterstage.

¹⁴ SeeRyan(2015)85114.

¹

⁵ ThislistisaslightlyevolvedversionofthelistofimmersivefeaturespublishedinAllan,DeJong, andDeJonge(2014).Myidentificationof fivegeneralaspectsofimmersionisbasedonWolf ’ s inventoryofprinciplesofaestheticillusion(seeWolf(2004)andhis ‘Introduction’ inWolf, Bernhart,andMahler(2013)).

¹

⁶ SeealsoWolf(2004)33940andWolf,Bernhart,andMahler(2013)434.Textsthatevokea specificlocationataspecifictimeandarerichindescriptionsofsensorydetailsand(vigorous)action/ movementarelikelytoinduceembodiedsimulationeffects(see,e.g.,Zwaan(2004);Sanfordand Emmott(2012)1556;andHuitink(Chapter9ofthisvolume)).

¹

⁷ Preferably,thespatialcluesareassociatedwithadeicticcenterwithinthedescribedscene:seealso belowunder(II)Perspective.

¹⁸ Writtendescriptionsofobjectsandeventsarenecessarily ‘ gappy ’:theydonotfeedeveryconceivable detailtothereader.This ‘gappiness’ isnotnecessarilydetrimentaltotheimmersiveexperience,sincea readerwillbeableto fillinthedetailsonthebasisofhisorhergeneralworldknowledgeandpersonal experiences.Foradiscussionoftheroleofcognitiveschemataandscriptsinunderstandingliterarytexts,

(II) Perspective:Thetextchoosesitsspatio-temporaldeicticcentrewithin thedescribedscene.Preferably,ittakestheperspectiveof(isfocalizedby) acharacterwithwhomtheaddresseemayidentifyandfeelempathy.¹⁹

Specificlinguisticindicationsofthisperspectiveshiftare:

(a) proximal (‘here’ and ‘ now ’)deixis(e.g.historicpresent);

(b)imperfectaspect(indicatingan ‘internalviewpoint’);²⁰

(c)subjective-evaluativevocabularywhichcanbeascribedtoacharacter.

(III) ‘Transparency’ ofthetext:Thetextdirectstheaddressee’sattentionto thestoryworld,thatis,itdefocusesfromthetextitselfasamediumand fromthenarratorasamediatingvoice.²¹Theartificialityofthetextis concealed;thenarratorremainsinvisible.Morespecifically,wewill find: (a)nometanarrativeelements(e.g.narratorcomments);

(b)directorfreeindirectdiscourse;²²

(c)noelementsdrawingattentiontotheconventionalityofthetextual (literary)genre.²³

(IV) Interestandemotionalinvolvement:Thethemeofthetextisofstrong interesttotheaddressee.Thetextcontainselementselicitingtheaddressee’ s emotionalresponse(e.g.subjective-evaluativevocabulary).²⁴ Thetext (segment)iscrucialtothemainstorylineandcreates suspense.²⁵

(V) PrincipleofMinimalDeparture:²⁶ thestoryworldshouldnot(oronly minimally)departfromthe ‘realworld’ asweknowit:thestoryworldshould beinternallyconsistentandsubjecttothesamerulesas ‘reallife’.²⁷

seeStockwell(2002)75 89.Thereisalsoempiricalevidencefortheimportanceofinferencesfromworld knowledge(cognitivescenarios)indiscoursecomprehension(SanfordandEmmott(2012)12 44).

¹⁹ ThisisanaspectofRyan’ s emotionalimmersion (Ryan(2015)10614).SeealsoWolf(2004)340 andWolf,Bernhart,andMahler(2013)478.

²

⁰ Forthemimeticqualityoftheimperfect,seeBakker(1997b),(2007).Rijksbaron(2012)= Rijksbaron(2019)13369discussestheimperfect’sfunctionincharacterfocalization.

²¹Cf.Ryan’srequirementoftransparencyofthemediumintheexperienceofvirtualreality(Ryan (2001)568,11819).SeealsoWolf(2004)340,3423andWolf,Bernhart,andMahler(2013)501.

²²Fortheeffectofimmediacy,involvement,andvividnessoftheuseofdirectspeech,see,e.g.,Leech andShort(2007)276.Thereisalsosomeempiricalevidenceforthiseffect;seeSanfordandEmmott (2012)18190.

²³ Arsestcelareartem.ToputitinRussianformalistterms, defamiliarization isdetrimentalto immersionsinceitdrawstheaudience’sattentiontotheartisticdevicesusedintheliteraryworkand challengestheaudience’sfamiliarperceptionsoftheworld.Itencouragestheaudiencetotakeadistanced, observingstancewithrespecttotherepresentedworld.AsnotedbyRyan,self-reflexivityinliteratureis incompatiblewiththeexperienceofimmersion(Ryan2001):areaderisnotabletoattendmentallytothe verbalmediumandtheworlditrepresentsatthesametime.Anexampleisthedisruptionofthedramatic illusionascausedbythebreachingofthefourthwallinAristophaniccomedy.Forthisreason,immersive worksofarttendtobeseriousratherthancomic.SeealsoWolf(2004)341,344 5.

²⁴ Cf.also(II)Perspective(c).

²⁵ SeealsoWolf(2004)342andWolf,Bernhart,andMahler(2013)50.

²⁶ SeeRyan(1991)4860.

²

⁷ Departuresmaybetoleratediftheycanbeexplainedbygenericconventions(seeRyan(1991)51, Wolf(2004)340,andWolf,Bernhart,andMahler(2013)46).Forexample,wemayassumethat Homericepicfeaturessuchastheuseofhexameters,theepic Kunstsprache,andtheappearanceofthe

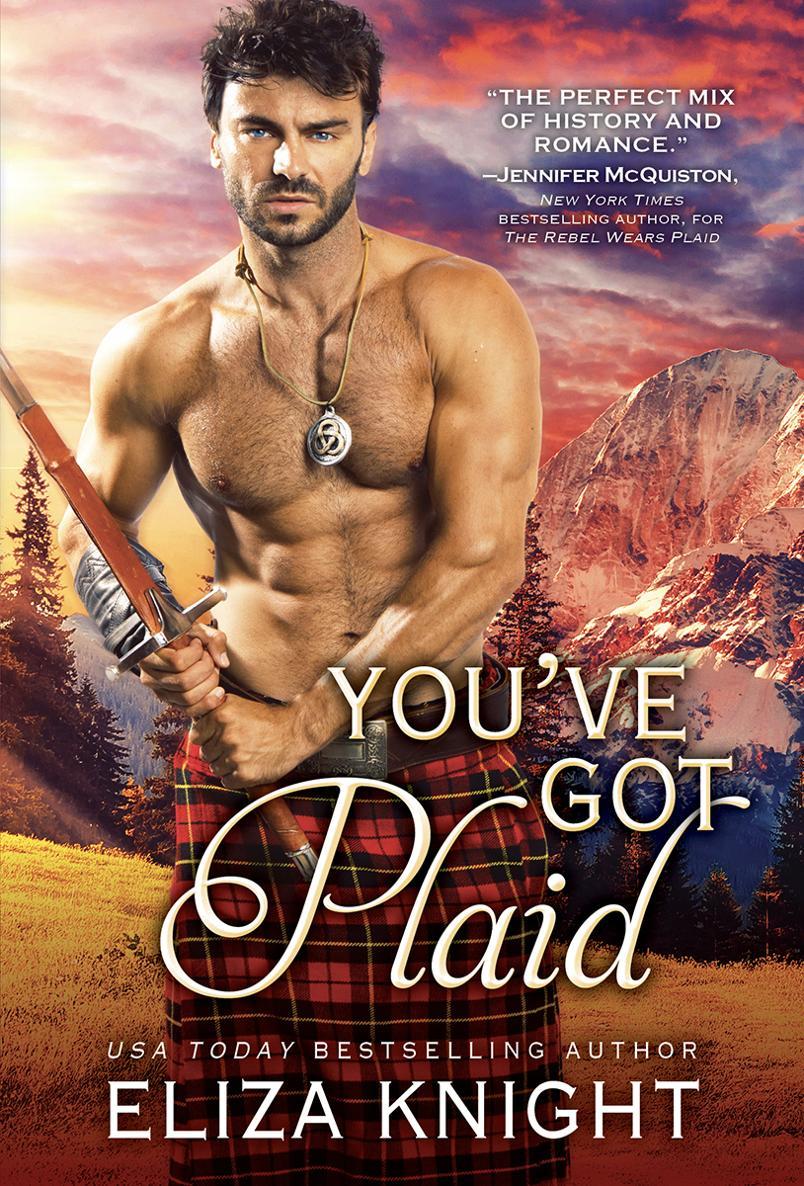

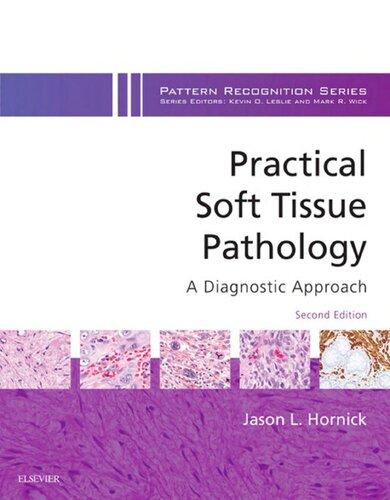

TheexperienceofimmersioncanberepresentedgraphicallyasinFigure1.1.

Thereaderexperiencesamentaltransportationintothestoryworld(arrow) whichisinthefocusofthereader’sattention(thickcircle).Awarenessofthe surroundingrealworld(includingthereader’sself-awareness)andthemediating worldofnarration,ontheotherhand,ismentallybackgroundedbutnotentirely absent(dashedcircles).²⁸

Immersioncanbeausefuladditiontothetheoreticalapparatususedtoanalyse Greeknarrative.Animportantvirtueoftheconceptofimmersionisthatitis firmlyembeddedincurrentnarratologicalandlinguistictheory:itrelatestowellestablishednarratologicalconceptssuchasspeed,order,focalization,narratorial visibility,suspense,andgenreconventions.Immersionalsosubstantiallydraws

godsonthescenedidnotdisrupttheaudience’simmersiveexperience(eventhoughthesedeviatefrom theaudience’sreal-lifeexperiences)sincethesefeaturesconformtotheepicgenericconventions associatedwithapoeticperformance.Toputitdifferently,theydonotviolatetheaudience’ s expectationsbydisruptingexistingcognitiveschemas(cf.Stockwell’ s schemapreservation;Stockwell (2002)7981).WemayevenassumethatthespeciallanguageofHomericepic enhances theaudience’ s feelingofimmersioninthestoryworldasitfunctionsasacatalysttohelptheaudiencetobementally transportedintotheexoticpastheroicworlddistinctfromtheaudience’spresentworld;seeClay(2011)15.

²⁸ The figureisamoreelaborateversionofa figurepresentedbyDannenberg(2008)24.

narratee narrator

Storyworld

World of Narration

Real World

writer reader

Figure1.1 Thereader’sexperienceofimmersioninthestoryworld