An Introduction to Landscape Ecology Foundations and Core Concepts

At rst glance, this image (Figure 1.1) evokes a pastoral landscape, with cultivated elds of row crops and perhaps some lavender growing in the distance. Fields are neatly arrayed and delineated, some apparently fallow or newly plowed, others bearing regular furrows or bisected by roadways and irrigation canals. The landscape bears the strong imprint of human land use, with all of its lines and orderliness. Upon closer inspection, however, we come to realize that this is not an actual photograph, but an abstraction, a quilted landscape created using colored swatches of silk crepe. Nevertheless, the quilt does depict an actual landscape— the ‘ elds of salt’ in a region of the San Francisco Bay Area where natural wetlands have been converted to salt ponds for industrial use. As with our earlier impression of an agricultural landscape, this image similarly calls to mind the dramatic effects humans can have on landscapes through the alteration of their structure and function. A quilt is thus an apt metaphor for the landscape: as patchworks of

Figure 1.1 Fields of Salt, art quilt. © Linda Gass 2007.

different land covers and land uses, landscapes are similarly shaped by humans and, like quilts, they are sometimes in need of restoration and conservation.

Why Study Landscape Ecology?

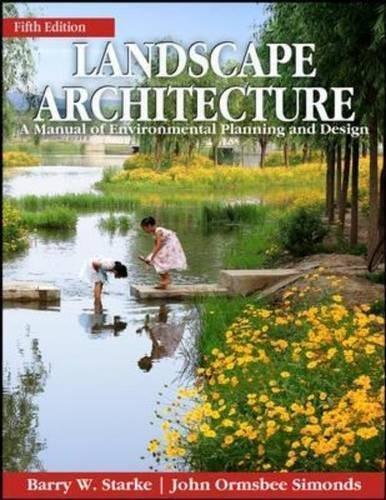

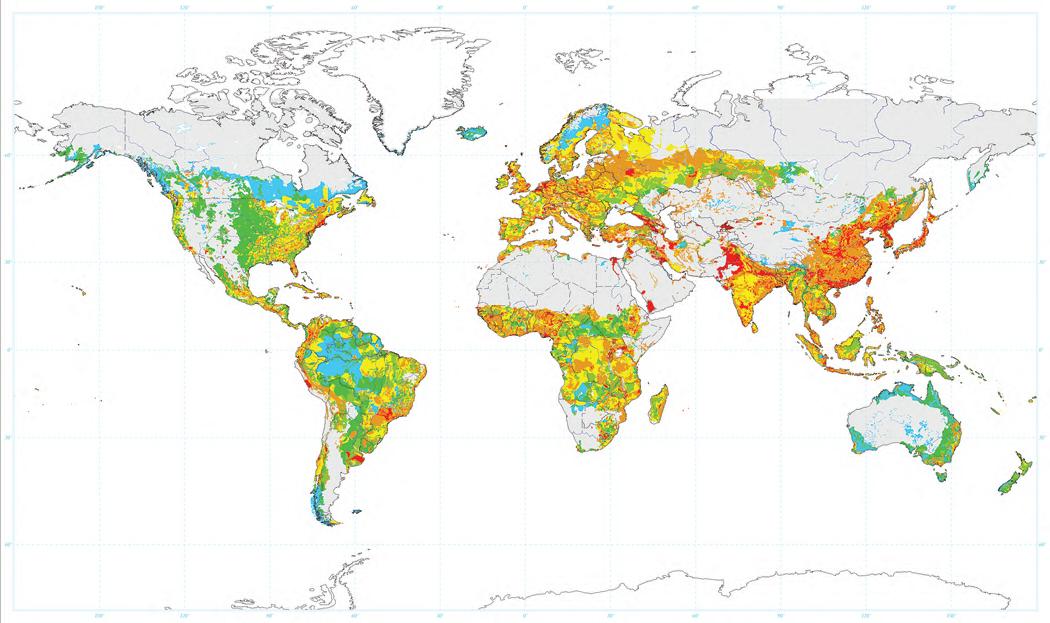

We are living in a transformative era. Since the start of the Industrial Revolution, humans have issued in a new geological period—the Anthropocene—a ‘geology of mankind’ (Crutzen 2002). There are few places on Earth that have not been touched, either directly or indirectly, by humans (Vitousek et al. 1997; Figure 1.2). A burgeoning global population has increased both our need for land and the mass consumption of resources provided by that land. Modern technologies have made it more ef cient and economical for us to exploit the land and its resources, while global transportation networks and the globalization of economies have increased not only the interconnections among diverse regions of the globe, but also the extent of our impact on those regions. With landscapes worldwide being transformed at a rate and scale that rivals even the largest of natural forces, it should come as no surprise that a new and comprehensive science is needed

to tackle the complex ecological and societal consequences of human land use.

Minimal impact

Low impact

Moderate impact

High impact

Very high impact

Indeterminate

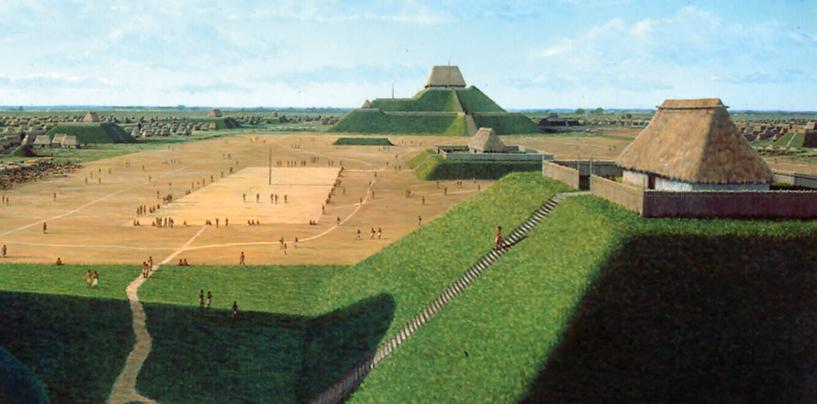

The human modi cation of landscapes is hardly a recent phenomenon, however. Landscapes bear the imprint of past human land uses that in some cases date back centuries or even millennia. We humans have a long history of altering the landscapes around us, whether it be for quarrying stone, felling forests, plowing grasslands, draining wetlands, or damming and diverting rivers. For example, the indigenous people of the Mississippian culture, which ourished more than a thousand years ago throughout the river valleys of the midwestern and southeastern United States, transformed these oodplain landscapes through the creation of huge earthen mounds. One cannot help but marvel at the industry of the people who created these earthen pyramids, the largest of which stands 30 meters tall and covers 6 hectares, solely by packing mud and clay by hand. The largest Mississippian site is Cahokia, located just east of modern-day Saint Louis, Missouri (Figure 1.3). During its heyday (around 1100), Cahokia was one of the world’s great cities, with a population exceeding that of many European cities of the time, including London. The inhabitants of Cahokia were km

02,0006,0004,0008,000

Figure 1.2 Anthropic landscapes. Humans have a pervasive in uence on landscapes. Worldwide, few areas have not been affected—either directly or indirectly—by our activities. This global anthropic landscape map was generated from the overlay of a global human population density map with a global land-quality map to illustrate the distribution of anthropic tension zones where humans are having the greatest impact, particularly on soil resources.

Source: USDA-NRCS (2000).

Pristine

Source: (A) © National Geographic

early landscape architects, having carefully designed and engineered these mounds, which evidently required a great deal of technical expertise (Dalan et al. 2003). The largest mounds were likely built for ceremonial and religious purposes, and may have been topped by large buildings where the elites or rulers lived (Figure 1.3B). Although the stonemasonry involved in the construction of the better-known pyramids of ancient Egypt and Mesoamerica is also a marvel of engineering, these earthen mounds, which persist today as small hills dotting the landscape (Figure 1.3A), are a testament to the ability of even pre-industrial humans to physically shape the landscape.

The effect of human land use on landscapes—past, present, and future—is a major focus of landscape ecology. As humans alter the landscape, they also invariably alter its ecology, including the ecological ows and myriad ecological interactions that occur within the landscape. All landscapes are heterogeneous in that they are made up of a variety of landforms, ecosystems, vegetation communities (habitat types), and land uses, re ecting the different processes—physical, biological, and anthropogenic—that have shaped them. In turn, the structure of the landscape—its composition and con guration of habitat types or land uses—in uences the biological and physical processes

(B)

Figure 1.3 Cahokia. Cahokia was a cultural mecca in its day (1050–1250), a bustling urban center at the heart of what was then one of the largest cities in the world. (A) Aerial view of Cahokia today, with Monks Mound in the distance. (B) Artist’s rendition of what the Central Plaza with Monks Mound might have looked like during Cahokia’s heyday (~1100).

Creative/Alamy Stock Photo. (B) Courtesy of Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site, painting by L. K. Townsend.

that give the landscape its form. The ows of materials, nutrients, and organisms across the landscape are all important for the maintenance of critical ecological functions that contribute to the structure and diversity (i.e. heterogeneity) of the landscape in the rst place. Landscape ecology, then, is the study of the reciprocal effects of pattern on process: how landscape patterns in uence ecological processes, and how those ecological processes in turn modify landscape patterns (Risser et al. 1984; Turner 1989; Pickett & Cadenasso 1995; Turner et al. 2001). From this standpoint, humans are but one of the many forces that shape landscapes, albeit an important one.

In this introductory chapter, we place the emergence of landscape ecology as a relatively new scienti c discipline within its historical context by discussing the contributions from its elemental disciplines to its development, as well as the different schools of thought that have subsequently shaped its science and practice. Next, we highlight the core principles and major research themes in landscape ecology, which will be addressed more fully throughout the remainder of this textbook. We conclude with an overview of the book itself to help guide our study of landscape ecology.

Birth of a Discipline

In comparison to many other established elds in the natural and social sciences, or even to other areas of ecology, landscape ecology is a relatively new science. If we mark the birth of a scienti c discipline by the establishment of a professional society and/or a scholarly journal dedicated to its study, then landscape ecology emerged only about 35 years ago. Since it is rare to witness the birth of a discipline, a brief overview of its development is warranted, especially since this provides insight into the different perspectives on the study and practice of landscape ecology today.

The International Association for Landscape Ecology (IALE) was of cially founded in October 1982 at an international symposium held in the spa town of Pieštʼ any, in what is now western Slovakia. Its conception, however, occurred some 18 months earlier, in April 1981, at the rst international congress for landscape ecology at Veldhoven in the Netherlands (Antrop 2007). The formation of IALE thus represented the culmination of a long gestation among European ecologists and geographers, who as far back as the late 1960s and early 1970s had perceived the need for a broader, multidisciplinary science concerned with the management, planning, and design of landscapes (Naveh 2007; Wu 2007a). The IALE now consists of more than two dozen regional chapters from all over the world, representing individual countries as well as collectives of nations (e.g. Africa-IALE and IALE-Europe).

The largest of the IALE regional chapters is the United States chapter (US-IALE).1 Its inaugural meeting was held in January 1986 in Athens, Georgia (USA), just a few years after the establishment of the international governing body, re ecting an early interest in the eld by a number of American ecologists. Indeed, several American ecologists had been among the attendees at the landscape ecology symposia in Europe. In April 1983, 25 ecologists and geographers were invited to a three-day workshop in Allerton Park, Illinois (USA) to discuss opportunities for developing landscape ecology in North America (Risser et al. 1984; Risser 1995). The Allerton Park workshop represents a pivotal moment, not just for landscape ecology in North America, but for the discipline as a whole. The workshop is widely credited with establishing a new paradigm for landscape ecology, one that continues to guide it today—a focus on the reciprocal effects of landscape pattern and ecological process (Wiens 2008; Wu 2013).

At the outset, the idea of landscape ecology sounded appealing. Urgency and a sense of responsibility for the quality of landscapes motivated us and we realized that the integration of ecology and human activities was not only necessary but could bring new insights to the study of landscapes.

Forman & Godron (1986)

At around this same time, the publication of two seminal textbooks (one by Zev Naveh and Arthur Lieberman [1984], and the second by Richard Forman and Michel Godron [1986]) further helped to elevate and establish landscape ecology as a new discipline. The discipline’s agship journal, Landscape Ecology, published its rst issue in 1987, with American ecologist Frank Golley at its helm (Golley 1987). The journal has since developed into one of the top-ranking journals in the elds of geography and ecology (Wu 2007a). Not surprisingly, these early scholars and leading gures in landscape ecology were all participants in the initial European symposia, the Allerton Park workshop, or both.

The mid-1980s thus represented a watershed period for landscape ecology. The rise of landscape ecology at that time can be attributed to a number of factors related to theoretical and conceptual developments in ecology, technological advances, and increasing concern over human impacts on the environment. In the eld of ecology, several developments had particular relevance for landscape ecology: (1) island biogeography and metapopulation theory provided a new paradigm

1 The United States regional chapter voted in April 2019 to become IALE-North America, so as to better re ect its multi-national constituency.

for studying the effects of habitat patchiness on ecological systems; (2) there was a growing recognition of the importance of spatial scaling in the design and interpretation of ecological research; and (3) there was a shift from viewing ecological systems as closed (isolated) and driven toward an equilibrium state to viewing them instead as open (connected) and dynamic systems. In addition, technological advances in remote sensing, geographic information systems (GIS), and computer processing were making it possible to collect, store, analyze, and display unprecedented amounts of geospatial data over vast spatial extents, allowing for the rst time a true study of landscapes at broad spatial scales. Finally, the growing concern over human modi cation of the environment, especially in the heavily industrialized nations where landscape ecology originated, was a motivating force in the development of the discipline in the mid-1980s. The cumulative effects of human land use were clearly responsible for the loss and fragmentation of habitats that in turn were contributing to a global extinction crisis (e.g. Wilcove et al. 1998). Indeed, it is no coincidence that conservation biology also emerged as a scienti c discipline during the 1980s (Soulé 1985).

Although landscape ecology may not have emerged as a scienti c discipline until the 1980s, its antecedents can be traced back decades and even centuries. Well before there was a journal or a society of landscape ecology, there were societies and journals devoted to human ecology, land-use planning, and design (i.e. landscape architecture). Journals such as Landscape Planning and Urban Ecology (which have since been merged into a single journal, Landscape and Urban Planning) were rst published in the mid-1970s, more than a decade before Landscape Ecology. Journals and professional organizations concerned with the management of economically important landscapes such as forests and rangelands date from the rst half of the 20th century. Ecologists and geographers can trace their academic roots back even farther, to the many professional societies and their journals that appeared in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Indeed, a German geographer, Carl Troll, is widely credited with coining the term ‘landscape ecology’ (landschaftsokologie) in 1939 (Troll 1939). Over the ensuing decades, Troll continued to re ne his view of landscape ecology, which he de ned as ‘the study of the main complex causal relationships between the life communities and their environment’ that ‘are expressed regionally in a de nite distribution pattern (landscape mosaic, landscape pattern)’ (Troll 1971). Troll’s training in geography, coupled with his early interest in botany, contributed to his unique understanding of interactions between geomorphology and vegetation patterns, particularly in the mountainous regions of the world, where he used aerial photographs

to study elevational vegetation gradients. As one of the rst landscape ecologists, Troll deftly blended the spatial approach of the geographer with the functional approach of the ecologist, a combination that has come to epitomize landscape ecology today (Turner et al. 2001).

Regional Perspectives on Landscape Ecology

Early contributions by European geographers and ecologists to the nascent eld of landscape ecology helped de ne—as well as gave name to—a new discipline. The European perspective pervades the science and practice of landscape ecology in many parts of the world today, although the subsequent establishment of landscape ecology in North America followed a very different trajectory during its development. In this section, we consider how these different regional perspectives have contributed to the development of landscape ecology.

European Perspective

European landscape ecology has a long tradition that has greatly in uenced its subsequent development and character. Europeans recognized early on that society was placing increasing demands on landscapes and that the environmental problems created by those demands were far too complex to be solved individually by existing disciplines, but instead required a new multidisciplinary perspective to address them (Antrop et al. 2009). From its earliest beginnings, then, European landscape ecology has been marked by a strong holistic and human-centered perspective (Wu & Hobbs 2007; Figure 1.4A).

In densely populated Europe, the main concern is on cultural landscapes and the natural and cultural heritage related to these. Most traditional landscapes lose rapidly their ecological and heritage values, which are considered as “natural and cultural capital.” There is a growing need to plan future landscapes in an increasingly urbanized society and polarised environment in the perspective of sustainable development and participatory planning. Antrop et al. (2009)

The concept of holism, as applied to the landscape, implies that its functioning cannot be understood simply by studying some aspect of it in isolation. The Dutch landscape ecologist Isaak Zonneveld, for example, was a proponent of the land-unit concept (Zonneveld 1989). The land-unit concept was rst proposed by the Australian land surveyor and mapper Clifford Stuart Christian, who advocated for a systems approach to

(A)

Figure 1.4 Regional perspectives on landscape ecology. The development of landscape ecology in the 1980s followed different trajectories in (A) Europe and (B) North America.

Source: After Wiens 1997.

the study of landscapes as ‘hierarchical wholes.’ In his view, a landscape is a system of interacting land units, de ned as ‘parts of the land surface having a similar genesis and [that] can be described similarly in terms of the major inherent features of consequence to land use—namely, topography, soils, vegetation and climate’ (Christian 1958, p. 76). We’ll return to this idea of landscapes as hierarchical systems in Chapter 2. For now, it is worth noting that the land-unit approach was ultimately an effort to develop a more systematic way of de ning, mapping, and integrating multiple attributes of landscapes (e.g. landforms, soils, vegetation, or land uses) that had traditionally been studied individually by different types of scientists. Beyond providing a more holistic approach to the study of landscapes as integrated wholes, however, the land-unit approach was also presented as a more ef cient and cost-effective land survey method and mapping tool that could aid in ‘the evaluation of the suitability of landscape for any kind of land use’ (Zonneveld 1989, p. 68). This approach thus epitomizes the practical and humancentered applications of European landscape ecology, whose primary aim has been to facilitate the evaluation,

mapping, planning, design, and management of landscapes for human land use (e.g. Zonneveld 1972; Naveh & Lieberman 1984; Schreiber 1990).

In many respects, the European view of landscapes, and thus of landscape ecology, is a re ection of the political and economic integration of Europe itself. With the integration of the European Communities in 1967 and the subsequent formation of the European Union in 1993, the rapidly changing face of the European landscape is now being shaped largely by common policies, such as the Common Agricultural Policy. Although the EU does not have a common landscape policy, there has been some progress at the political level in recognizing the broad value of landscapes beyond the economic or resource bene ts they provide. In 1995, the EU’s European Environmental Agency published its Dobríš Assessment, a report on the state of the European environment, which includes a chapter devoted to landscapes and their importance to the future of the European environment (Stanners & Bourdeau 1995). Most notably, the chapter emphasizes the importance of preserving the unique character and diversity of landscapes as part of the natural and cultural heritage of Europe. The Dobríš Assessment is thus credited with helping to draw the attention of policymakers to the various pressures that are leading to a decline in the diversity, distinctiveness, and value of landscapes throughout Europe (Antrop et al. 2009).

The Dobríš Assessment was in uential in the Council of Europe’s development of the European Landscape Convention, which went into force in 2004. The convention is an international treaty for the comprehensive protection, management, and planning of landscapes throughout Europe, including all natural, rural, and urban landscapes as well as inland waters and coastal marine areas, regardless of their condition (it includes ‘everyday, outstanding and degraded landscapes’).

The landscape has an important public interest role in the cultural, ecological, environmental and social elds, and constitutes a resource favourable to economic activity and whose protection, management and planning can contribute to job creation;

The landscape contributes to the formation of local cultures and is a basic component of the European natural and cultural heritage, contributing to human well-being and consolidation of the European identity;

The landscape is an important part of the quality of life for people everywhere;

The landscape is a key element of individual and social well-being and its protection, management and planning entail rights and responsibilities for everyone.

Preamble to the European Landscape Convention

Remarkably, the establishment of the European Landscape Convention was principally motivated not by economic concerns over the provisioning services provided by landscapes (although they are seen as one of its bene ts), but rather by a concern for societal wellbeing and the quality of life for European citizens; that is, by the public good. Landscapes are perceived to have strong cultural as well as natural values and, as such, become part of a country’s identity and cultural heritage. Because the landscape plays such an important role in the well-being of individuals and society at large, the Convention argues, all Europeans are adversely affected by a deterioration in the quality of their surroundings. The public should thus have some say, as participating stakeholders, in how landscapes are managed, rather than leaving these sorts of decisions solely to those with specialized or economic interests. By agreeing to the terms of the European Landscape Convention, participating nations have acknowledged their collective duty to make provision for the protection, management, and planning of landscapes to fulll these sociocultural values, especially at the local or regional level. As of February 2019, the convention had been rati ed by 39 of the 47 member states in the Council of Europe.

In response to these developments, IALE-Europe was formed in 2009 as a new supranational chapter of the International Association for Landscape Ecology (Antrop et al. 2009). IALE-Europe aims to promote collaboration among members of Europe’s diverse academic community of landscape ecologists and to make their collective expertise available to institutional and societal stakeholders as well as the policymakers involved in decisions about landscape management and planning at the European level.

North American Perspective

The emergence of landscape ecology in North America was clearly in uenced by its success in Europe, which had excited the interest of a number of ecologists in both the United States and Canada (Figure 1.4B). As mentioned previously, the landscape ecology movement in North America can be traced to the workshop held in 1983 at Allerton Park, a former estate now overseen by the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign near Monticello, Illinois. Most of the 25 invited participants were from the United States, although individual attendees from Canada and France were also present (Wiens 2008). This small group, most of whom were systems ecologists, formed the nucleus of what became a new movement in landscape ecology (Wu 2013).

The speci c developmental pathway that landscape ecology took in North America might thus be attributed to a strong founder effect (Wiens 1997), as it deviated from its European roots as a result of the particular

backgrounds and research interests of this small gathering of ecologists and geographers. This is immediately apparent from the de nition of landscape ecology given in the report of that workshop, as the study of ‘the relationship between spatial pattern and ecological processes [that] is not restricted to a particular scale’ (Risser et al. 1984, p. 255). In contrast to the European perspective, this de nition is clearly more ecological and explicitly spatial; it also allows for the possibility that landscapes—and thus landscape ecology—need not be concerned solely with broad spatial scales, an issue we’ll return to later.

At the Allerton Park workshop, participants were asked to consider how landscape ecology might contribute to four major areas of inquiry (Risser et al. 1984):

1. How heterogeneity in uences the ux of organisms, materials, and energy across the landscape.

2. The formative processes, both past and present, that give rise to landscape patterns.

3. How heterogeneity affects the spread of disturbances, such as re, across the landscape.

4. How natural resource management might be enhanced by adopting a landscape ecological approach.

Thus, the workshop put forward many of the nowrecognizable themes of landscape ecology—the importance of heterogeneity, scale, and disturbance dynamics for understanding the reciprocal effects of spatial pattern and ecological process (Wu 2013). In retrospect, this is not surprising, given that many of the participants had also been active in the International Biological Program (1964–1974), whose ambitions included the development of complete systems models to predict the effects of anthropogenic and environmental change on entire ecosystems (e.g. on total productivity), in addition to the more general application of ecosystem science to natural resource management (Boffey 1976). Thus, many of the Allerton Park participants were already, to quote one of them, ‘primed for thinking about landscapes in terms of ows and uxes, energy and materials, and management implications’ (Wiens 2008, p. 127).

Given the ecological and systems modeling backgrounds of many of the Allerton Park participants, it was perhaps inevitable that landscape ecology in North America would take on a more quantitative and spatial modeling character than that of its European congener (Figure 1.4). The Allerton Park workshop occurred at a time when microcomputers and GIS were both in their infancy, but already several participants were keen to exploit the opportunities these new technologies afforded landscape ecology, especially for analyzing broad-scale patterns of landscape change (Iverson 2007). The need to quantify and compare the

spatial attributes of landscapes spurred the development of new landscape metrics (O’Neill et al. 1988a) as well as spatial modeling approaches to permit the statistical comparison of landscape data with known distributions (i.e. neutral landscape models; Gardner et al. 1987). Patch-based ecological theory, such as the theory of island biogeography, metapopulation theory, and patch dynamics theory, provided a quantitative and predictive framework that helped inform initial landscape ecological research into how patch structure could in uence the structure and dynamics of ecological systems (MacArthur and Wilson 1967; Levins 1970; Pickett & White 1985).

The early focus on natural resource management is also quite telling. Whereas Europeans were principally concerned with the management of cultural landscapes, North Americans were more focused on natural or managed landscapes, of which vast tracts still remain. Many of these lands are owned and managed by the federal government. For example, the federal government owns more than a quarter of the land in the United States (28%), amounting to about 2.6 million km2 (Gorte et al. 2012). For comparison, this is an area roughly two-thirds the size of the entire European Union. Most federal lands are located in the western half of the United States, where 42% of the land area is federally owned, and in Alaska, where 62% of the land area is federally owned. Federal lands are held in the public trust, and most (96%) are managed for a variety of competing purposes (timber, grazing, mining, recreation, wildlife, conservation) by four different government agencies: Forest Service, National Park Service, Bureau of Land Management, and Fish and Wildlife Service. The US National Forest System, for example, encompasses 780,000 km2, which is about the size of the total land area of Germany, UK, Slovakia, Denmark, and the Netherlands combined. In Canada, forest covers about 4 million km2 (equivalent to the size of the EU), and 93% of this forested land is publicly owned (crown land) and managed under the purview of either the provincial (77%) or federal (16%) crown (Annual Report, The State of Canada’s Forests 2011). Little wonder then that forest and natural resource management should play such a major role in the subsequent development and application of landscape ecology in North America (Boutin & Hebert 2002; Liu & Taylor 2002; Bissonette & Storch 2003; Perera et al. 2007).

Globalization of Landscape Ecology

Although interesting from a historical standpoint, these different regional perspectives should not be taken too literally, at least in terms of how landscape ecology is currently practiced. There are many North American landscape ecologists who are concerned with land-use planning and management issues, just as there are

many European landscape ecologists who study the relationship between landscape pattern and ecological process. Thus, to quote Wu & Hobbs (2007, p. 277):

It is evident that the European and North American approaches to landscape ecology have differed historically. On the one hand, the European approach is characterized by a holistic and society-centered view of landscapes . . . On the other hand, the North American approach is dominated by an analytical and biological ecology-centered view of landscapes . . .This dichotomy, of course, is an oversimpli cation of the reality because neither of the two approaches is internally homogeneous in perspectives and because both have been changing as an inevitable consequence of increasing communications and collaborations among landscape ecologists worldwide.

These two traditional landscape perspectives have been variously adopted—and adapted—in other areas of the world, such as Australia, Latin America, and China. Australian landscape ecologist Richard Hobbs has characterized the Australian approach as taking ‘a pragmatic middle road which combines both aspects’ (Hobbs & Wu 2007, p. 7). Landscape ecology in Latin America, whose emergence led to the formation of three IALE chapters (Argentina and Brazil in 2005, and Chile in 2016) likewise appears to have embraced both perspectives. For example, the rst bulletin for the IALE-Chile chapter (published May 2018) de nes landscape ecology as ‘an interdisciplinary science that studies the spatial variation of landscapes [across] a wide range of scales,’ but also emphasizes the chapter’s commitment to applying landscape ecology to the sustainable use of natural resources and ‘to work and collaborate on public policies on management issues related to landscape ecology, such as territorial planning, ecosystem services and the effects of global change’ (https://www.iale-chile.cl/). The development of landscape ecology in China was similarly in uenced by the North American perspective at the outset, but now appears to be embracing the more holistic European perspective that places greater emphasis on landscape planning, design, and environmental management (Fu & Lu 2006, pp. 239–240):

China is a developing country with [a] large human population and diversi ed environmental conditions. The drive for socioeconomic development is very strong, and at the same time environmental quality, resource usability and ecological security are also important concerns for the sake of regional sustainable development. Therefore, it is crucial to harmonize the relationships between human population growth, regional economic development and environmental conservation. Consequently, future landscape ecological research in China should take the responsibility of

Social Sciences

Archaeology

Sociology

Political science

Economics

Psychology

History

Law (policy)

Architecture and design

Human geography

Economic geography

Regional/urban planning

Transportation planning

Geography

Physical geography

Regional geography

Cartography

GIS science

Remote sensing

Geostatistics

Landscape

Ecology

Human ecology

Resource management

Conservation biology

Sustainable development

Zoogeomorphology

Paleobiology

Biogeography

Ecological modeling (spatially explicit)

Ecology/Evolution

Movement ecology

Population ecology

Population genetics

Invasion ecology

Disease ecology

Community ecology

Systems ecology

Spatial ecology

Figure 1.5 Domain of landscape ecology. Landscape ecology is a multidisciplinary science that occurs at the intersection of elds in ecology/evolution, geography, and the social sciences.

exploring the complex interactions between human activities and landscape dynamics under a holistic landscape framework, in which humans are treated as landscape ingredients equivalent to other biotic and abiotic components of the landscapes . . . Many aspects, including ecological, economic and cultural, should be integrated. The holistic approach is effective in studying the multifunctionality of Chinese landscapes.

Today, the apparent difference in perspectives on landscape ecology is perhaps less a ‘European versus North American’ distinction than an ‘applied science versus basic science’ dichotomy found in many elds in the ecological, biological, and physical sciences. Although this dichotomy is a false one in any science, it is especially so in landscape ecology. The relationship between science and practice is reciprocal (Wiens 2005). The two perspectives are in fact complementary, and both are ultimately necessary to the science and practice of landscape ecology (Hobbs & Wu 2007). Landscape ecology is a vibrant, cross-disciplinary science that not only integrates research across the natural and social sciences (Figure 1.5), but also transcends the

traditional boundaries between science and practice by promoting the integration of interdisciplinary research with stakeholder concerns about the environmental and societal consequences of human land use (Wu 2006).

Core Concepts of Landscape Ecology

From the start, landscape ecologists have emphasized the structure and function of landscapes and how landscapes change over time (Forman & Godron 1986). Three attributes are characteristic of all landscapes and provide the basis for quantifying and comparing them:

1. Landscape structure pertains to the diversity and spatial arrangement of landscape elements (e.g. habitat patches).

2. Landscape function refers to the interaction among these spatial elements (e.g. the ow of energy, nutrients, species, or genes among habitat patches).

3. Landscape change refers to how landscape structure and function vary over time.

Research in landscape ecology is motivated by several guiding principles or core concepts (Wiens 1997, 2005) that are variously related to these three landscape characteristics.

Landscapes are heterogeneous. By de nition, landscapes are mosaics of different landforms, ecosystems, habitat types, or land uses (Forman & Godron 1986; Forman 1995b). While landscapes are often viewed as comprising discrete elements (e.g. habitat patches, corridors, roads, water bodies), heterogeneity can also vary continuously over the landscape, as it does along an ecocline or ecological gradient. Different formative processes give rise to different landscape structures, a topic that we will explore further in Chapter 3. One consequence of heterogeneity, however, is that elements of the landscape mosaic—the collection of land covers and landuse types—are likely to vary in quality or suitability for different species. This will be a recurring theme in the later chapters of this book, where we deal with the ecological consequences of landscape structure.

Landscapes are diverse in form and function. We can characterize landscapes based on a diverse array of features related to their geomorphology (e.g. mountainscapes), primary land cover or land use (e.g. forest landscape), a speci c ecological or biological function (e.g. landscape of fear; Laundré et al. 2001; soundscapes, Pijanowski et al. 2011), the amenities or commodities they provide (e.g. agricultural landscape), or in relation to human occupation and values (urban landscape; cultural landscape). Landscapes need not be landlocked, however. If heterogeneity is a de ning characteristic of landscapes, then marine and freshwater systems would similarly qualify, for they also exhibit heterogeneity in the distribution of substrates, habitats, resources, and environmental conditions. Thus, we can de ne riverine landscapes (Wiens 2002) and marine landscapes or ‘seascapes’ (Pittman et al. 2011). These are all ‘landscapes’ in that they comprise spatially heterogeneous areas, whose study might therefore bene t from a landscape ecological perspective.

Landscapes are scale-dependent. Although landscapes have traditionally been viewed on human terms, as areas of broad spatial extent, there has been a persistent movement within landscape ecology to de ne a landscape simply as a spatially heterogeneous area (Turner 1989) that is scaled relative to the process or organism of interest (Wiens & Milne 1989). Two species that occur within the same habitat, such as grasshoppers and bison (Bison bison) on the tallgrass prairies of North America, are likely to have very different perceptions of the landscape in terms of the distribution and availability of their preferred forage, given the different scales at which they each operate. The idea that landscapes are

scale-dependent acknowledges that patchiness (i.e. heterogeneity) may exist simultaneously across a range of scales. Multiscale patch structure may re ect the different scales at which various processes or disturbances that shape the landscape operate. Such a view also broadens the de nition of ‘landscape,’ and thus the domain of landscape ecology. From this viewpoint, any type of spatial distribution at any scale could constitute a landscape. This perspective is important, for it recognizes that landscape ecology is not simply ‘regional ecology’ or ‘broad-scale ecology,’ but a research paradigm for investigating the effect of spatial pattern on ecological processes at any scale. We will discuss this perspective more fully in Chapters 2 and 3

Landscapes are dynamic. As the biochemist and science ction writer Isaac Asimov once famously observed, ‘the only constant is change.’ All ecological systems are dynamic, and landscapes are no exception. Disturbances across a wide range of scales, from those occurring over minutes within a few square centimeters to those operating over tens of millennia across thousands of square kilometers, have all contributed to the landscapes we see around us today. Landscapes are thus better viewed as ‘shifting mosaics’ than as static systems in some sort of equilibrium (Wu & Loucks 1995). Understanding how anthropogenic landscape change compares to the natural disturbance regime, and whether it ts within the range of historical variation for a particular landscape, is important for evaluating the potential impacts of human activities on the structure and function of landscapes. We will discuss this topic more fully in Chapter 3. Furthermore, the rate at which landscapes change may be just as important as—if not more important than—the resulting structural changes (e.g. in the amount or con guration of habitat) for certain ecological responses or landscape functions. For example, species may exhibit a lagged response to rapid habitat loss or fragmentation, such that an assessment of a population’s responses to landscape change might underestimate its actual risk of extinction (Schrott et al. 2005). We will consider the effects of landscape dynamics on a variety of ecological responses throughout this book.

Spatial context is important. Given that landscapes are heterogeneous, we can expect that ecological dynamics will vary spatially. For example, if habitats vary in their suitability for a particular species, then population growth rates of that species will likewise vary among habitat types. High-quality habitats should support viable populations, whereas low-quality habitats cannot (Pulliam 1988). Our understanding of the population dynamics within patches thus requires information on habitat quality (in other words, population dynamics are habitat-dependent). However, habitat quality

may also be spatially dependent, such that two sites within the same habitat might vary in quality depending on their speci c location (i.e. their spatial context). For example, reproductive success for forest-breeding songbirds might be higher for individuals that nest in the center of a habitat patch than at its margins (where nest predation rates tend to be higher), or in a forest patch surrounded by second-growth forest than in one surrounded by agricultural elds (where again, nest predation rates are expected to be higher), or in a landscape that is still predominantly forested than in one that has very little forest cover remaining (where nest predation rates are uniformly greater; Donovan et al. 1997). Thus, spatial context may well be important for understanding what goes on within individual patches (or landscapes), and will de nitely be important for understanding what goes on between patches.

Ecological ows are important. Because spatial context is important, we should anticipate that the nature of the patch boundary and the intervening matrix—the mosaic of land-cover or land-use types that occurs between habitat patches—can in uence the magnitude of ecological ows among patches. Patch boundaries may be porous to the movement of certain organisms but impermeable to others, depending on how different organisms perceive and respond to the structure of the habitat edge, which occurs at the juxtaposition of different vegetation communities. The transition between vegetation types may be abrupt, creating what is known as a ‘hard edge,’ especially if organisms are unwilling or unable to cross that boundary, or may be a more gradual transition from one habitat type to the next, creating a ‘soft edge.’ Flows may also occur between ecosystems, such as across the land-water interface. Agricultural or stormwater runoff from the surrounding landscape is a familiar source of nonpoint-source pollution in marine and freshwater systems. However, these ows do not occur in just one direction, from land to water, but may also occur in the opposite direction, from water to land, as in the case of marine subsidies along coastal areas or desert islands (Polis & Hurd 1996). Asymmetrical ows across patch or system boundaries can have profound effects on the dynamics within, as well as between, patches or systems on the landscape. This will be a recurring theme in many of the later chapters of this book, where we consider the effects of asymmetrical ows (individual movement and dispersal, gene ow, and nutrient ows; Chapters 6, 9, and 11) on various ecological processes. Connectivity is important. The notion that organisms, materials, or nutrients ow to varying degrees among patches or systems on the landscape implies that some areas of the landscape are connected, at least functionally, even if they are not obviously connected in a

structural sense (e.g. via habitat corridors). Connectivity can be considered an emergent property of landscapes; it emerges as a consequence of the interaction between ecological ows and the landscape pattern (Taylor et al. 1993; With et al. 1997). It could thus be argued that much of landscape ecology is ultimately concerned with the measurement and study of connectivity. Connectivity is important for understanding the propagation of disturbances across the landscape; the movement and redistribution of organisms, materials, and nutrients; the resulting structure and dynamics of populations; gene ow and population genetic structure; the spread of invasive species and diseases; community patterns and dynamics; and ecosystem structure and function (Chapters 6–11). Thus, connectivity will be a pervasive theme throughout this book, and an entire chapter (Chapter 5) is devoted to this important concept.

Landscapes are multifunctional. Humans are the principal driver of landscape change worldwide, as landscapes are increasingly being transformed and used for a variety of ecological, societal, and economic functions (Ojima et al. 1994b; Vitousek et al. 1997; Figure 1.2). Landscapes are thus multifunctional in that they provide humanity with an array of goods and services. Therefore, landscape management requires a means of identifying and resolving the con icts that inevitably arise in response to competing interests and valuation systems (Mander et al. 2007). Sustainability is a key concept in landscape ecology (Wu 2006) and is the basis for sound ecosystem and natural resource management (Liu & Taylor 2002; Bissonette & Storch 2003). Recall that landscape ecology arose in response to the perceived need to manage resources more holistically and at a broader landscape scale. Although we will consider the management implications of landscape ecology throughout this book, the nal chapter (Chapter 11) examines in greater detail how principles derived from landscape ecology can be used to meet the environmental and societal challenges that stem from human land use (i.e. landscape sustainability).

Organization of this Book

The demands of time and your personal interests will necessarily dictate how you use this text. Because many diverse elds contribute to landscape ecology, readers of this book are also likely to be quite diverse. Thus, although the book’s organization represents a natural ordering of topics (at least from the author’s perspective), your individual interests and needs will obviously dictate which topics are emphasized, and in what order.

The rst ve chapters cover not only the discipline of landscape ecology (introduced in this chapter), but also its major research themes, including issues of spatial

and temporal scale (Chapter 2), landscape heterogeneity and dynamics (Chapter 3), landscape pattern analysis (Chapter 4), and landscape connectivity (Chapter 5). These chapters provide many of the core concepts that will be emphasized repeatedly throughout the remainder of the book. Chapter 5, on landscape connectivity, could be considered a bridge chapter, given that it spans the domains encompassed by landscape pattern analysis in the chapter that precedes it and ecological responses to landscape pattern in the chapters that follow.

Chapters 6–11 consider the ecological consequences of spatial pattern for a wide range of processes and phenomena involving individual movement and dispersal (Chapter 6), population distributions and dynamics (Chapter 7), population spatial spread (Chapter 8), gene ow and population genetic structure (Chapter 9), community structure and dynamics (Chapter 10), and ecosystem structure and function (Chapter 11). Although readers should feel free to focus on chapters that are of particular interest, the chapters have been developed and arranged in a hierarchical fashion, such that material in later chapters builds on concepts and approaches presented in earlier chapters.

Each chapter provides a mix of basic concepts, examples, and case studies along with more advanced topics related to the theoretical foundation, quantitative methods, or modeling applications relevant to a particular area of research. The beginning student, practitioner, or casual reader wishing for an overview

of the basic concepts should focus on the introductory sections of the chapter and the chapter summary points at its end. More advanced students and research scientists are likely to bene t most from the more in-depth coverage of methodologies, analyses, and modeling considerations featured in most chapters. However, this book is not an instruction manual. Although issues involved in the collection, analysis, and modeling of spatial data are discussed, the primary objective is to give you the necessary information with which to evaluate these concerns from the standpoint of your own interests, research, or management needs. The intent is to provide an overview of available tools and methods, along with some general guidance as to their use, and then direct interested readers to additional resources where they can obtain more detailed information on the topic.

Finally, as a pedagogical tool, this book has been organized around the way in which these topics are presented in my own course on landscape ecology. It is hoped that the discussion questions at the end of each chapter will challenge the reader to think more deeply or broadly about the topics presented within the chapter. These questions can also help facilitate discussion within a classroom or seminar setting. Some of these questions can be used for class assignments or as essay questions on examinations, and thus might prove especially useful in that regard for instructors—and students—of landscape ecology.

Chapter Summary Points

1. Landscape ecology studies the reciprocal effects of spatial pattern (heterogeneity) and ecological processes. It emphasizes the structure, function, and change in landscapes over time.

2. The ways in which human land-use activities modify landscape structure and function are a major research focus in landscape ecology, which provides a scienti c basis for understanding and managing landscapes as well as the goods and services they provide.

3. Landscape ecology is a relatively new scienti c discipline, having become established some 35 years ago in Europe before spreading to North America, Australia, and elsewhere. Its historical roots can be traced back much earlier, however. The German geographer Carl Troll rst coined the term ‘landscape ecology’ (landschaftsokologie) in 1939 in reference to his study of the interaction between geomorphology and vegetation patterns along elevational gradients.

4. The rise of landscape ecology in the mid-1980s may be attributed to three factors: (i) an increasing

concern over human impacts on the environment, especially in the heavily industrialized nations where landscape ecology rst originated; (ii) technological advances in remote sensing, geographic information systems, and computer processing, which made the collection, analysis, and modeling of geospatial data over broad regional areas not only feasible, but ef cient; and (iii) conceptual and theoretical developments within the eld of ecology, especially patch-based theory, a growing recognition of the importance of spatial scale for the design and interpretation of ecological research, and a shift away from equilibrium theories to dynamic views of ecological systems such as landscapes.

5. Different regional perspectives in uenced the early development of landscape ecology as a science. In Europe, the focus was more on land-use planning and the management of cultural landscapes; the focus was thus squarely human-centered. In North America, the development of the discipline was more heavily

in uenced by ecological theory and spatial modeling applications, and thus the focus was more on the study and management of ecological landscapes. Landscape ecology has bene tted from these diverse perspectives and has matured into a cross-disciplinary science that integrates the natural and social sciences and transcends the traditional boundaries between science and practice.

6.Research in landscape ecology is motivated by eight core concepts: (i) landscapes are heterogeneous, and this heterogeneity is important for understanding spatial processes across the landscape; (ii) landscapes are diverse and are found in aquatic and marine systems as well as terrestrial ones; (iii) landscapes are scaledependent, in that heterogeneity exists across a

wide range of scales, and thus landscape ecology is not restricted simply to the study of broad spatial extents; (iv) landscapes are dynamic, such that the rate of landscape change can be just as important as the magnitude of change for understanding and predicting its consequences; (v) spatial context is important for understanding the distribution and dynamics of ecological systems; (vi) ecological ows are important to many ecological phenomena and are in uenced by the differential permeability of landscape elements and the nature of patch boundaries; (vii) connectivity is important and emerges as a consequence of the interaction between landscape pattern and ecological process; (viii) landscapes are multifunctional, which requires that resources and land uses be managed sustainably.

Discussion Questions

1.In what ways might regional differences in how landscape ecology is de ned and practiced (e.g. the European versus North American perspectives) contribute positively to the growth and development of the eld? In what ways might such regional differences be detrimental?

2.Although landscapes are traditionally viewed as encompassing broad areas of land, a different view of landscapes as simply ‘spatially heterogeneous areas’ de ned relative to the

organism or process of interest has since emerged within the eld of landscape ecology. Discuss how this more general de nition of ‘landscape’ affects the science and practice of landscape ecology.

3.Which of the core concepts in landscape ecology could be applied to the system in which you are currently working? How might a landscape ecological perspective thus prove useful to the study or management of this system?